Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 1

Monitoring Mechanisms and Intellectual Capital Disclosure among Banks in the GCC

Abood Mohammad Al-Ebel, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Zuaini Ishak, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Keywords

Board Effectiveness, Audit Committee Effectiveness, Monitoring Mechanisms, Intellectual Capital Disclosure, Banks, GCC.

Introduction

Studies to examine the association of voluntary disclosure and corporate governance mechanisms have been done extensively in different countries for various sectors (e.g. Alfraih & Almutaw, 2017; Jaffar, et al., 2013; Saha & Akter, 2013). The current study focuses on a particular type of voluntary disclosure, which is intellectual capital (IC) disclosure since it is an important dimension of voluntary disclosure for which there is a growing demand (Holland, 2003, Burgman & Roos, 2007). IC is the key driver of the company’s competitive advantage and disclosing it reduces investors’ uncertainty about future prospects and facilitates a more precise valuation of the company (Barth et al., 2001; Bukh et al., 2005; Holland, 2006; Li et al., 2012). Despite the importance of IC disclosure, the company is disclosing it voluntarily (Petty & Cuganesan, 2005; Zhang, 2001). IC is specific to a particular company and cannot be seen from other companies. Smaller shareholders are at disadvantages if the information about IC is not disclosed because they do not have access to the information. Thus, corporate governance mechanisms are more critical for IC than other types of disclosure inasmuch as it involves information asymmetry more (Aboody & Lev, 2000; Hidalgo et al., 2010). Agency cost due to opportunities for moral hazard, adverse selection and other opportunistic behaviour of management will be increased (Aboody & Lev, 2000; Holland, 2006). Therefore, governance mechanisms might act to reduce agency cost by enhancing voluntary disclosure of IC information (Ramadan & Majdalany, 2013).

A combination of several governance mechanisms can be considered better for reducing the agency cost and protecting the interests of shareholders because of the effectiveness of corporate governance being achieved via different channels (Cai et al., 2008) and a particular mechanism’s effectiveness depends on the effectiveness of others (Davis & Useem, 2002; Rediker & Seth, 1995). Ward et al. (2009) argued that it is advisable to view corporate mechanisms as a set of mechanisms to protect and not in isolation from each other. The effectiveness of board of directors, which is an important internal corporate governance mechanism, depends on its characteristics like board size, board independence and frequency of board meetings, non-duality and board committees (e.g. Alfraih & Almutaw, 2017; Baldini & Liberatore, 2016; Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Li et al., 2008; Ruth et al., 2011; Saha & Akter, 2013). Thus, it could be said that boards that have a higher score for these characteristics are better able to protect the shareholder by increasing the level of disclosure than boards that have a lower score. In the same vein, it can be said that the effectiveness of the audit committee depends on its characteristics like audit size, independence, frequency of meetings and audit financial expertise (e.g. Akhtaruddin et al., 2009; Akhtaruddin & Haron, 2010; Saha & Akter, 2013). Ward et al. (2009) argued that previous studies considered each mechanism separately in addressing agency problems as they ignored the idea that effectiveness of single mechanism depends on the other mechanisms. In addition, Agrawal and Knoeber (1996) proof that the results on the effectiveness of single mechanism might be misleading by showing that the effect of some single mechanisms on firm performance disappeared in the combined model. Based on the idea that the impact of internal governance mechanisms on corporate disclosures is complementary; increase (decrease) of the characters that enhance the board and audit committee effectiveness leads to increase (decrease) of the level of voluntary disclosure. This current study diverges with the prior studies on IC disclosure (that looked to each board characteristic individually) by examining the effect of board characteristics as a bundle of mechanisms in protecting shareholders interest. In more specific words, this study examines the relationship between score of characteristics (that affect board and audit committee effectiveness) and IC disclosure.

In addition to board of directors, institutional ownership has been suggested as a monitoring mechanism to solve agency problem (Allen & Gale, 1999). This issue is quite conceivable particularly in Arab Gulf countries where the legal protection of investor rights and legal enforcement are weak (Chahine, 2007). Furthermore, GCC countries are characterized as having considerable agency problem between large and small shareholders (Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 2010). According to Chahine and Tohmé (2009) in Arab countries, where companies are controlled by large shareholder that are affected by political ties and also family involvement, institutional investors have role in mitigating agency problems between the large and minority shareholders. For example they might provide the necessary checks and balances for agency problems of CEO duality, while allowing for the benefits of focused leadership (Chahine & Tohmé, 2009). Previous studies from other countries examine institutional investor at the aggregate level with voluntary disclosure (eg. Ajinkya et al., 2005; Donnelly & Mulcahy, 2008; Saha & Akter, 2013). However, not all institutional investors have same capabilities to protect minority. Foreign strategic investors may have greater experience, monitoring capabilities and credibility than domestic (Claessens et al., 2000; Douma et al., 2006). In other words, they may be more pressure-resistant to locally-generated principal–principal problems (Brickley et al., 1988; Kochhar & David, 1996; Tihanyi et al., 2003). Therefore, the current study also examines IC disclosure in GCC countries by dividing institutional into the foreign and domestic institutional.

Allen and Gale (1999) also highlight that the competition among firms is an effective mechanism to reduce the agency conflicts between the managers and shareholders because it disciplines the management with competitors` management. Hart (1983) and Li (2010) argued that competition works as a disciplinary mechanism on the leadership in firms by providing owner with information about the management performance that can be used to mitigate moral hazard problems. So, the current study is also investigate on whether or not the competition works as monitoring mechanism to increase the level of IC disclosure.

Based on the economic theory framework, particularly agency theory, this IC disclosure study is designed to provide empirical evidence in banking sector in the GCC countries in relation to effectiveness of board and audit committee, foreign and domestic institutional ownership; and market competition. The GCC countries comprise the Kingdom of Bahrain, the State of Kuwait, the State of Qatar, the Sultanate of Oman, the State of United Arab Emirates and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which all have a mature, efficient, stable and profitable banking system. These countries share some common economic, cultural and political similarities, which by far outweigh any differences they might have (Al-Muharrami et al., 2006). In 2008, the GCC countries' economy accounted for around 1.8 per cent of the world's total GDP of around $61 trn (Al-Hassan et al., 2010). The banking sector is one of the largest sectors in GCC economies and there are more bank stocks traded in GCC stock markets than stocks of any other industry. This sector in GCC continues to be well capitalized across the board with capital adequacy ratios well above minimum standards and comfortable leverage ratios by international comparisons (Al-Hassan et al., 2010). The GCC countries generally have a moderate to high level of financial development. They score the highest on regulation and supervision, as well as on financial openness when compared to the remaining countries in the Middle East and the North African (MENA) region (Creane et al., 2004). The competition in the banking sector at GCC is high and corporate governance in this sector is better than other sectors in terms of putting in place board committees like audit and nominating committee. Although the competition is high and corporate governance is better than in other sectors, the information asymmetry is however high and the level of disclosure is low in the banking sector (Chahine, 2007).

The present study contributes to the literature in a number of ways. First, it provides empirical evidence on the relationship of the score of effectiveness of the board of directors and audit committee with IC disclosure in GCC countries. Second, the significant results between foreign institutional investors and IC disclosure provide a clear indication that foreign institutional investors are effective to monitor management and solve the agency problem between the small and large shareholder in environment where legal protection of investors is low. Lastly, by examining the relationship between market concentration (proxy of competition) as monitoring mechanisms and voluntary disclosure of IC, this study contributes to IC, voluntary disclosure literature from the lens of agency.

The remainder of the paper is structured in the following sequence. The next section discusses research framework and hypotheses development. The following section presents research method while the findings are reported in section 4. The last section of the paper summarises its key findings and finally, after discussing some of its limitations, a number of future research is suggested.

Researh Framework And Hypotheses Development

The researchers and analysts have not reached unanimous agreement on the definition of IC disclosure and its components. However, one of the most widely accepted definitions of intellectual capital, which is supported by a number of prominent authors (Sveiby, 1997; Brennan & Connell, 2000; Sullivan, 2000), is formed by three sub constructs: Internal capital, external capital and human capital. Internal capitals include patents, copyright, management philosophy, technology and administrative systems. On the other hand, external capitals include customer capital comprising relationships with customers and suppliers, brand names, trademarks and reputation. Next are human capitals, which refer to employees’ competence such as skills, knowledge, qualification, experience.

Disclosing information about IC in the corporate annual report is not costless. Williams (2001) argued that voluntary disclosure of IC could affect the competitive advantage of company since it provides signal to competitors of possible value-creating opportunities. According to Vergauwen and Alem (2005), a firm may be at the competitive disadvantage when it discloses sensitive information to outside investors. However, from the literature review, it could be deduced that disclosure of IC has advantages for company, investors and markets. For example, IC disclosure can help organisations to formulate their strategies, to diversify and expand decisions and to use as a basis for compensations (Marr et al., 2003). The disclosure provides the information about the real value and future performance of a company. Hence, it is considered as relevant information for investors and users (Bukh et al., 2005). Furthermore, IC disclosure may be considered to resolve uncertainty about the firm which leads to the increase in the stock price, reduction in volatility of stock prices and a decrease in capital cost (Kristandl & Bontis, 2007). Recognising these advantages of IC disclosure, several attempts have been made through several models to measure and report IC. For example, Kaplan and Norton’s Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1992), Sveiby’s Intangible Assets Monitor (Sveiby, 1997) and Skandia’s Value Scheme (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997) are among the most popular models used to construct reports on intellectual capital.

Reviewing of literature reveals that majority of studies used Sveiby’s (1997) framework that categorizes IC into three categories namely, internal structure, external structure and employee competence. Guthrie and Petty (2000) used the framework of IC as proposed by Sveiby (1997) after modifying the names of the categories into internal capital, external capital and human capital, to examine the level of IC disclosure in Australia. The IC reporting framework suggested by Guthrie and Petty (2000) has been followed by several authors in many countries such as Brennan (2001) in Ireland, Bozzolan et al. (2003) in Italy, Vandemaele et al. (2005) in Netherlands, Sweden and UK, Li et al. (2008) in UK and Yi and Davey (2010) in China.

Voluntary disclosure is a good example to apply agency theory, in the sense that managers have more information about the company than the owner. Managers can make credible and reliable communication to the market and they can enhance the value of the company by reducing agency costs. Previous studies suggest IC disclosure to be increased in banking sector since it provides valuable information to users of financial statements, as it reduces agency costs and information asymmetry (Ramadan & Majdalany, 2013).

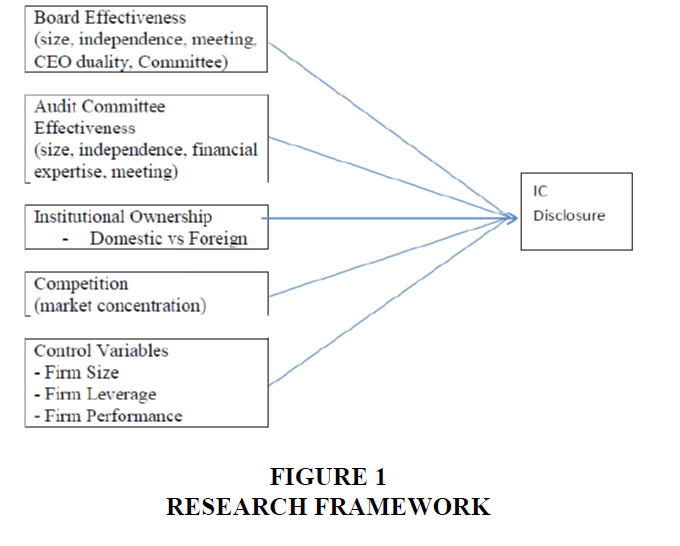

Agency theory suggests internal corporate mechanisms such as board of directors (e.g. Akhtaruddin & Haron, 2010; Baldini & Liberatore, 2016; Cerbioni &Parbonetti, 2007; Hidalgo et al., 2010) and audit committees (Akhtarudin & Haron, 2010; Gan et al., 2008) as important mechanisms to force managers to disclose more information. In addition to board of directors and audit committee, institutional ownership and competition have been suggested by previous studies as a monitoring mechanism to solve agency problem between management and shareholders (Allen & Gale, 1999).

The aim of this study is to extend the previous studies by examining the relationship between the effectiveness of the board of directors and also audit committee; foreign and domestic institutional ownership; and market concentration with IC disclosure. The research framework is shown in Figure 1.

Effectiveness of Board of Directors and IC Disclosure

The board of directors is one of the important elements in internal corporate governance mechanisms. The board plays the key monitoring role in dealing with agency problems (Aktaruddin et al., 2009; Chobpichien et al., 2008; Singh & Van der Zahn 2008). Fama and Jensen (1983) argued that by monitoring and controlling the management, the board of directors can reduce agency conflicts where managers may have their own preferences and always fail to act on behalf of the shareholders. Moreover, it can be argued that the board of directors plays an important role in protecting not only the shareholders’ interests but also other stakeholders’ interests against management’s self-interests. To this extent, Hermalin and Weisbach (1991) suggested that the board of directors should provide solutions to mitigate the agency problems faced by companies.

Chobpichien et al. (2008) noted that independence, size, frequency of board meetings and non-duality of the chief executive officer (CEO) are the important factors that determine the effectiveness of board that could force management to disclose more information to outside parties. Singh and Van der Zahn (2008) and Ruth et al. (2011) pointed out that the enhancement of board of directors in terms of board size, board composition and leadership structure could improve board effectiveness and its capacity to monitor the management to the extent of increasing the possibility of providing more information about IC to outside investors. Cerbioni and Parbonetti (2007) suggested that the board is effective in improving the IC disclosure when it is small in size, has independent chairman with majority of its members also been independent, has active members in audit, nomination and compensation committee. These elements, if present, would enhance the monitoring role of board of directors. However, it has been suggested that the optimal combination of these mechanisms can be considered better to reduce the agency cost and to protect the interests of all shareholders because the effectiveness of corporate governance is achieved via different channels (Cai et al., 2008). According to Chobpichien et al. (2008) and Ward et al. (2009), it is important to look at corporate mechanisms as a bundle of mechanisms to protect shareholder interests and not in isolation from each other because these governance mechanisms act in a complementary or substitutable fashion (Chobpichien et al., 2008). This is in addition to Hill (1999) who posited that it is desirable to have a system which consists of several checks and balances mechanisms and none of them is accountable by itself to provide solution to all the problems faced by companies. Based on the above arguments, this study suggests that when the characters that enhance the effectiveness of board of directors increase, the level of IC disclosure also increases. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: There is a positive association between the effectiveness of the board of directors and IC disclosure.

Audit Committee Effectiveness and IC Disclosure

Abdifatah (2015) suggest the role of audit committee should be extending to improve disclosure including intellectual capital. Meanwhile, as mentioned earlier, the optimal combination of mechanisms can be considered to reduce the agency cost better because a particular mechanism’s effectiveness depends on the effectiveness of others (Davis & Useem, 2002; Rediker & Seth, 1995). DeZoort et al. (2002) argue that the audit committee effectiveness framework could increase considerably if the audit committee characteristics are studied together. Agrawal and Chadha (2005) suggest that independent directors with financial expertise are valuable in providing oversight financial reporting. Similarly, Mustafa and Youssef (2010) argue that audit committee independence is not effective unless the members are financial experts. Xie et al. (2003) argue that an audit committee whose members have a financial background and have frequent meetings serves better as an internal control mechanism and enhances oversight of the financial reporting. Saleh et al. (2007) argue that independent members who have financial expertise but do not attend meetings will not enhance the effectiveness of the audit committee in increasing the quality of financial reporting.

The number of previous studies that examines the relationship between effectiveness of audit committee and IC disclosure are small and provide unclear results. From the findings of such previous studies, it seems that the effectiveness of independent audit committee members to improve the disclosure depends on their expertise, auditing process and frequency of meetings. Therefore, examining the characteristics of the audit committee in isolation of each other may explain why those studies provide an unclear result. By giving a score to an audit committee based on its characteristics, this study proposes a positive association between the audit committees effectiveness score and IC disclosure. Thus, based on the arguments above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: There is a positive relationship between the score of the effectiveness of the audit committee and IC disclosure.

Domestic and Foreign Institutional Ownership and IC Disclosure

Hashim & Devi (2007) and Chahine & Tohmé (2009) argue that the institutional investors are the mechanism to protect the interests of minority shareholders in companies controlled by large shareholders rather than other internal corporate mechanisms, such as board size and the proportion of outside directors. The findings of previous studies from various countries support these arguments. Barako (2007) find that institutional investors enhance the level of disclosure for Kenyan companies. Ajinkya et al. (2005) find that institutional investors positively affect the properties of earning forecasts. Lakhal (2005) find that institutional investors have a positive relationship with voluntary earnings disclosure in French companies. Khodadadi et al. (2010) examine the relationship between institutional ownership and voluntary disclosure for 106 companies listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange during 2001-2005. They find that voluntary disclosure is positively related to institutional ownership.

Despite the institutional investor’s ability to mentor management and reduce the agency problem, their monitoring capabilities differ according to their nationality (Bhattacharya & Graham, 2009; Chahine & Tohmé, 2009; Ferreira & Matos, 2008; Rashid Ameer, 2010; Tihanyi et al., 2003). It was found that foreign institutions are more able to monitor the management and reduce the agency problem than domestic institutions. According to Chahine & Tohmé (2009) and Douma et al. (2006), the ability of domestic institutional investors to monitor the management and reduce the agency problem is usually affected by existence of ties and networks in the domestic business environment. Rashid Ameer (2010) argue that foreign institutional investors have superior strategies in monitoring managers as compared to domestic investors because they bring with them different cultural, ethical values and norms that might produce changes in the corporate internal controls and ethical practices (Chahine & Tohmé, 2009; Ferreira & Matos, 2008). Moreover, compared with domestic investors, foreign investors are less informed and face higher costs of acquiring information to monitor management. In addition, the foreign institutions take into account considerable risks, such as political and legal risks when they want to invest in foreign countries. For this reason, they will choose companies that have good corporate governance with more transparency and avoid companies that do not have good corporate governance with less transparency. This issue is quite conceivable, particularly in Arab countries where foreign institutional shareholders are more likely to outperform their domestic counterparts in terms of experience, organizational, monitoring and technological capabilities and credibility (Chahine & Tohme, 2009). According to Kobeissi & Sun (2010), the percentage of foreign institutions in GCC banks is higher compared to banks from the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region. Kobeissi and Sun (2010) find that the presence of foreign institutional investors in the banking industry in the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region is associated with a relatively better performance. Therefore, this study expects that given the heterogeneity in monitoring and organizational capabilities between domestic and foreign institutional, they will have a different impact on IC disclosure.

Therefore, based on the above arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: There is a positive relationship between domestic institutional ownership and IC disclosure.

H3b: There is a positive relationship between foreign institutional ownership and IC disclosure.

Industry Market Concentration and IC Disclosure

The banking industry in GCC countries is characterized as relatively concentrated with a few domestic players dominating the market (Al-Hassan et al., 2010). The term industry concentration refers to the combined market share of the leading firms. Theoretically, it is argued that increasing banking industry concentration leads to less competitive conduct (Al-Muharrami & Matthews, 2006; Delis & Papanikolaou, 2009). The idea that there is an inverse relationship between market concentration and competition has its roots in the structural-conduct-performance hypothesis that argues that the higher the concentration in a market, the lower the competition, providing a theoretical relationship between market structure (concentration) and conduct (competition) (Abbaso?lu et al., 2007; Bikker & Haaf, 2002; Rezitis, 2010).

According to Hart (1983) competition works as a disciplinary mechanism on the leadership in firms through information about the management` performance provided that can be used to mitigate moral hazard problems. Allen and Gale (1999) argued that the competition among firms is one of effective corporate governance mechanisms that reduce the agency problems between the managers and shareholders because it disciplines the management with competitors’ management which is strongest. Moreover, they argued that competition is one of reasons that makes the level effectiveness between the countries is different. Arun and Turner (2002) argued that one of ways that lead to improve the corporate governance in banking sectors in developing countries is competition between banks in these countries. Similarly Unite and Sullivan (2003) argued that increase the competition between the banking sectors as result to entry the foreign competitors enforce domestic banks to be more efficient on account of increased risk and to become less dependent on relationship-based banking practices. His argument based on competition leads to success in the development of institutional and legal frameworks for corporate governance and capital market regulation.

According to Li (2010), in case of competition the managers disclose more information in order to reduce the information asymmetry between the management and shareholders and reduce capital cost. Darrough and Stoughton (1990) argued that firms disclose more information in greater competition for two reasons. First, firm discloses more information in order to delay the potential competitors from enter its market. The second is reduce cost of capital by reduce the information asymmetry between the management and investors.

From the discussion above, it is reasonable to expect that banking industry concentration may influence bank’s IC disclosure because of its impact on competition. So it can be said, that banks which work in high competitive environment, less concentrated market, disclose more information about IC in their annual reports. Thus, this study is expecting a negative association between the extent of IC disclosure and the level of market concentration.

H4: There is a negative relationship between the level of market concentration and IC disclosure.

Research Method

Sample

The sampling frame consists of listed banks in GCC countries during the period of 2008-2010. However, all Kuwaiti listed banks (11 banks) and several banks in other GCC countries are excluded from the sample due to missing relevant information. The final sample consists of 137 observations over the period.

Measurements of Variables

Dependent Variable: IC Disclosure

To preserve the comparability of this study with previous research, the categories and sub-categories of IC captured are based on the index developed in a recent study by Zaman Khan and Ali (2010) (Table 1). The reasons for adopting Zaman Khan and Ali’s framework are: First, they developed their framework based on Sveiby’s framework which has later been modified by Guthrie and Petty (2000). Guthrie and Petty’s framework has been adopted and employed by other studies (e.g. Bozzolan et al., 2003; Vandemaele et al., 2005) with varying degrees of similarity. Zaman Khan and Ali’s framework is more-or-less the same with Brennan (2001), April et al. (2003), Abeysekera and Guthrie (2005) and Campbell and Abdul Rahman (2010). Second, Zaman Khan and Ali’s framework was applied on banking sectors, as a result, only those items that have been consistently identified as relevant and likely to be disclosed by banks were included. They have removed some items from Sveiby’s framework, on the grounds that these would be better reported within the internal management reports of banks and recognizing the fact that IC disclosures are new phenomenon in the banking sector.

| Table 1: Ic Framework Adopted For The Study | ||

| Internal capital | External capital | Human capital |

|---|---|---|

| Patent | Customers | Training |

| Copyright | Banks market share | Employees educational |

| Management philosophy | Business collaboration | qualification |

| Corporate culture | Franchising licensing | Work related knowledge |

| Management and | Banks reputation for services | Work related competencies |

| technological process | Bank name | Know how |

| Information system | Entrepreneurial spirit | |

| Networking system | ||

| Financial relations | ||

This study employs content analysis to measure IC disclosure (Guthrie et al., 2004; Li et al., 2008) because it allows repeatability and valid inferences from data according to the context (Krippendorf, 1980). In order to increase the reliability of the scores, this study used the steps applied by Milne and Adler (1999) and Guthrie, Cuganesan and Ward (2008) as follows: First, the disclosure categories were adopted from well-grounded, relevant literature such as Zaman Khan and Ali (2010) who adapted their framework from well-grounded, relevant literature such as Sveiby (1997) and Guthrie and Petty (2000). Second, in order to increase the validity of content analysis, this study used the sentence as the measurement unit (Milne & Adler 1999). Third, the coder underwent a sufficient period of training and pilot study was conducted in order to reach an acceptable level of the reliability of the coding decisions (Guthrie et al., 2008).

Independent Variables

The independent variables of this study are bored and audit committee effectiveness, institutional ownership and industry market concentration. This study follows the direction of prior studies and uses a composite governance score (e.g. Chobpichien et al., 2008) to measure board effectiveness. The governance score is composed of the following measures: Number of member in the board (board size), percentage of independent directors on the board, frequency of meetings, number of board sub-committee and non-duality structure. Consistent with prior studies, this study views that smaller and more independent boards that have high frequency of meetings, have at least three sub-committees and are not chaired by the CEO, as an effective boards. For each of the components (except for non-duality and number of board sub-committees) this study calculates the sample median. It assigns the value of one for high quality indicators (i.e., companies below the sample median for board size and above the sample median for percentage of independent directors and frequency of meetings). We then sum these values and plus the score of one for non-duality and also one for board with at least three sub-committees. Thus, board effectiveness score is ranged from 0-5. The audit committee’s effectiveness score is measured based on the combination of variables proxies for audit committee effectiveness that is a sums of the value given for four characteristics of the audit committee (independence, size, meeting frequency and number of members with financial expertise). Value of one is given to the audit committee that has equal or higher than sample median for each of the four characteristic. Audit committee effectiveness score is ranged from 0-A similar measure had been used by previous studies (Goh, 2009; Khanchel, 2007; Lara et al., 2007; Krishnan & Visvanathan, 2008). Domestic (foreign) strategic institutional ownership is measured as the sum of the ordinary shares held by the domestic (foreign) banks and financial institutions that hold 5% or more shares in the bank. Following Al-Muharrami and Matthews (2006), banking industry concentration is measured by using k-bank concentration ratio (CR3) which is based on summing only the market shares of the three largest banks in the total assets of the banking market.

Control Variables

The study uses firm size, profitability and leverage that were used widely as control variables in the empirical literature of corporate governance. The measurement used for firm size is natural logarithm of total asset (Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 2010). Profitability is measured as the ratio of net income, before extraordinary items, to the total assets (Al-Shammari & Al-Sultan, 2010; Naser et al., 2006). Following Chahine and Tame (2009) and Al-Shammari and Al-Sultan (2010), this study measures firm leverage by dividing total liabilities by the total of assets.

Statistical Analysis

Regression is employed to test the hypotheses in order to ascertain the relationship of each independent variable to the dependent variable of interest. The regression model in this study is presented below:

Where;

ICD=intellectual capital disclosure

Boardefct=score for effectiveness of board of directors

Auditefct=score for effectiveness of audit committee

DOMI=% of domestic institutional ownership

FORI=% of foreign institutional ownership

Con=market concentration

LnAsset=natural logarithm of total asset

ROA=return on assets

LEV=leverage

Empirical Results

Descriptive statistics

Panel A in Table 2 shows that the average number of IC disclosure is 86.72 sentences. The maximum value is 175 sentences and the minimum value is 17 sentences. With respect to IC disclosure categories, the table shows that the banks provided slightly greater number of information about internal capital at average of 47.83 sentences than both external capital and human capital disclosures, which scored 31.72 and 14.37, respectively. This result is consistent with prior studies (e.g. Ali et al., 2008; Bozzolan et al., 2003; Brennan 2001).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Panel B of Table 2, the summary descriptive statistics for the independent variables are presented. Average score for effectiveness of the board of directors and audit committee is 2.53 and 1.4, respectively. The percentage of foreign institutional shareholdings for the sample ranges from 0 to 35%, with average shareholdings of about 6.4%. In addition the statistic indicates that the average of market concentration of GCC banking sector for the entire three-year period is 44 The sample has an average leverage level of 72% and a ROA of 2%. The negative sign of the ROA implies that some of banks experience a loss during the investigation period.

Regression Result

Several diagnostic tests were run (i.e., normality, linearity, multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation tests) before running the multiple regression analysis to ensure the assumptions of the regression have been met and the results are valid. Table 3 presents the result of multiple regressions. As predicted, the study finds a positive association between board and audit committee effectiveness with IC disclosure. The coefficient is positive and significant (p-value<0.05). This result suggests that as score of characteristics for both the board and audit effectiveness increase, the level of IC disclosure increases. These results support positive relationship between level of effectiveness of the board of directors and committee with IC disclosure.

| Table 3: Regression Result | |||

| Coefficient | t-statistics | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boardefct | 0.17 | 2.47 | 0.01* |

| Audifct | 0.14 | 2.06 | 0.04* |

| DOMI | -0.03 | -0.49 | 0.62 |

| FORI | 0.41 | 5.96 | 0.00* |

| Con | -0.16 | -2.22 | 0.02* |

| ROA | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.38 |

| LEV | 0.32 | 4.58 | 0.00* |

| LnAsset | 0.19 | 2.70 | 0.00* |

| R2=0.41 | F=12 | Sig=0.00 | |

As shown in the table, the coefficients signs are as predicted between the foreign and IC disclosure. The result means as percentage of foreign ownership increase the level of IC disclosure will increase. The coefficients sign is as predicted the relationship between the concentration and IC disclosure is negative and significant which means as the competition 12 1528-2635-22-1-109

increase the level of IC increase. For the control variables, the result shows only size and leverage have significant positive relationship with IC disclosure. ROA is not significant in this study, however it is included in the study to control the firm performance since Li et al., 2008 posit that ROA might result from continuous investment in IC and that firms might disclose the information to signal the important of their decision in investing in IC for long term growth in the firm performance.

Discussion and Conclusions

There are several important findings revealed in this study. First, this study finds that as the level of the effectiveness of board of directors and audit committee increase (increase of the characters that enhance the board and audit committee ‘monitoring) the level of IC disclosure in bank annual reports increase. This result supports the agency theory and the idea that the impact of internal governance mechanisms on corporate disclosures is complementary. Second, the study shows that as the percentage of foreign ownership increase in banks, the level of IC disclosure increase, thus it can be said the foreign institutional works as a better monitoring mechanism than the domestic to solve the agency conflict between the large and minority shareholder in GCC banks. A possible explanation of this result is that monitoring role of domestic institutional is usually affected by the existence of ties and networks in the domestic business environment (Claessens et al., 2000; Douma et al., 2006). This situation is happening in Arab companies where there is great ease in social interactions and the formation of groups. So they get the information about the bank through their relationship with the management. Since disclosing information about IC maybe effect the competitive advantage, domestic institutional will not enforce the management to disclose IC to outside. This social dynamic does, however, serve to increase the potential for political or group ties that may introduce a degree of inertia to the organization and diminish the impact of corporate governance mechanisms (Chahine & Tohmé, 2009). The third finding of the study is consistent with argument of agency theory which say the competition enhances the effectives of the board of directors thus it works as external corporate mechanisms (Allen & Gale, 1999; Hart, 1983; Li, 2010). The findings of the study indicate that policy makers should increase the relaxation of entry barriers in order to increase the number of banks in their markets and to allow for the foreign institutional investors to monitor the management and improve the internal corporate governance and, consequently, lead to an increase in the level of disclosure.

This study has a number of limitations that might warrant future research. This study can be considered as an exploratory and thus more works are needed in specific areas to improve it. As the samples used in this paper only involve the GCC-listed banks, in future, more samples could be included for a longer period of time. The test of the hypotheses could also be extended to different type of firms (i.e., in other sectors) or for the same type of firms but in different context (i.e., other Arab countries or Asia). Second, this study did not examine the effect of the legal enforcement on IC disclosure due to the low legal protection of investor rights and legal enforcement in all the GCC. Legal protection of investor rights would affect policies of voluntary disclosure on IC. Thus, future researches should retest these hypotheses in different legal protection setting.

References

- Abbasoglu, F., Aysan, A. & Gunes, A. (2007). Concentration, competition, efficiency and profitability of the Turkish banking sector in the post-crises period. Working paper. 549.

- Abdifatah, A. (2015). The role of audit committee attributes in intellectual capital disclosures. Managerial Auditing Journal, 30(8/9), 756-784.

- Abeysekera & Guthrie, J. (2005). An empirical investigation of annual reporting trends of intellectual capital in Sri Lanka. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(3), 151-163.

- Aboody, D. & Lev, B. (2000). Information asymmetry, R&D and insider gains. Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2747-2766.

- Agrawal, A. & Chadha, S. (2005). Corporate governance and accounting scandals. Journal of Law & Economics, 48 (2), 371-406.

- Agrawal, A. & Knoeber, C.R. (1996). Firm performance and mechanisms to control agency problems between managers and shareholders. Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, 31(3), 377-397.

- Ajinkya, B., Bhojraj, S. & Sengupta, P. (2005). The association between outside directors, institutional investors and the properties of management earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 43(3), 343-376.

- Akhtaruddin, M. & Haron, H. (2010). Board ownership, audit committees' effectiveness and corporate voluntary disclosures. Asian Review of Accounting, 18(1), 68-82.

- Aktaruddin, M., Hossain, M.A., Hossain, M. & Yao, L. (2009). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in corporate annual reports of Malaysian listed firms. The Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 7(1), 1-20.

- Alfraih, M.M. & Almutawa, A.M (2017). Voluntary disclosure and corporate governance: Empirical evidence from Kuwait International. Journal of Law & Management, 59(2), 217-236.

- Al-Hassan, A., Oulidi, N. & Khamis, M. (2010). The GCC banking sector: Topography and analysis. Washington: International Monetary Fund IMF Working Paper Series.

- Ali, M.M., Khan, M.H. & Fatima, Z.K. (2008). Intellectual capital reporting practices: A study on selected companies in Bangladesh. Journal of Business Studies, 29(1), 82-104.

- Allen, F. & Gale, D. (1999). Diversity of opinion and financing of new technologies. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 8(1-2), 68-89.

- Al-Muharrami, S., Matthews, K. & Khabari, Y. (2006). Market structure and competitive conditions in the Arab GCC banking system. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(12), 3487-3501.

- Al-Shammari, B. (2007). Determinants of internet financial reporting by listed companies on Kuwait Stock Exchange. Journal of International Business and Economics, 7(1), 162-178.

- Al-Shammari, B. & Al-Sultan,W. (2010). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in Kuwait. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 7(3), 262-280.

- April, K.A., Bosma, P. & Deglon, D.A. (2003). IC measurement and reporting: Establishing a practice in South African mining. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4(2), 165-180.

- Arun, T.G. & Turner, J.D. (2002). Financial sector reform in developing countries: The Indian experience. The World Economy, 25(3), 429-445.

- Baldini, M.A. & Liberatore, G. (2016). Corporate governance and intellectual capital disclosure: An empirical analysis of the Italian Listed companies. Corporate Ownership & Control, 13(2), 187-201.

- Barako, D.G. (2007). Determinants of voluntary disclosures in Kenyan companies annual reports. African Journal of Business Management, 15, 113-128.

- Barth, M.E., Kasznik, R. & McNichols, M.F. (2001). Analyst coverage and intangible assets. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(1), 1-34.

- Bhattacharya, P.S. & Graham, M.A. (2009). On institutional ownership and firm performance: A disaggregated view. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 19(5), 370-394.

- Bikker & Haaf, K. (2002). Measures of competition and concentration in the banking industry: A review of the literature. Economic & Financial Modelling, 9(2), 53-98.

- Bozzolan, S., Favotto, F. & Ricceri, F. (2003). Italian annual intellectual capital disclosure. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4(4), 543-558.

- Brennan, N. (2001). Reporting intellectual capital in annual reports: Evidence from Ireland. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(4), 423-436.

- Brennan, N. & Connell, B. (2000). Intellectual capital: Current issues and policy implications. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(3), 206-240.

- Brickley, J.A., Lease, R.C. & Smith, C.W. (1988). Ownership structure and voting on antitakeover amendments. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 267-291.

- Bukh, P.N., Nielsen, C., Gormsen, P. & Mouritsen, J. (2005). Disclosure of information on intellectual capital in Danish IPO prospectuses. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 18(6), 713.

- Burgman, R. & Roos, G. (2007). The importance of intellectual capital reporting: Evidence and implications. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8(1), 7-51.

- Cai, J., Liu, Y. & Qian, Y. (2008). Information asymmetry and corporate governance. Drexel College of Business Research Paper Series.

- Campbell, D. & Rahman, M.R.A. (2010). A longitudinal examination of intellectual capital reporting in Marks & Spencer annual reports, 1978-2008. The British Accounting Review, 42(1), 56-70.

- Cerbioni, F. & Parbonetti, A. (2007). Exploring the effects of corporate governance on intellectual capital disclosure: An analysis of European biotechnology companies. European Accounting Review, 1(4), 791-826.

- Chahine, S. (2007). Activity-based diversification, corporate governance and the market valuation of commercial banks in the Gulf Commercial Council. Journal of Management and Governance, 11(4), 353-382.

- Chahine, S. & Tohmé, N.S. (2009). Is CEO duality always negative? An exploration of CEO duality and ownership structure in the Arab IPO context. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(2), 123-141.

- Chobpichien, J., Haron, H. & Ibrahim, D. (2008). The quality of board of directors, ownership structure and level of voluntary disclosure of listed companies in Thailand. Euro Asia Journal of Management, 3(17), 3-39.

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S. & Lang, L. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 81-112.

- Creane, S., Goyal, R., Mobarak, A.M. & Sab, R. (2004). Financial sector development in the Middle East and North Africa. Working Paper.

- Darrough, M.N. & Stoughton, M. (1990). Financial disclosure policy in an entry game. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 12, 219-243.

- Davis, G.F. & Useem, M. (2002). Top management, company directors and corporate control. Handbook of Strategy and Management.

- Delis, M. & Papanikolaou, N. (2009). Determinants of bank efficiency: Evidence from a semi parametric methodology. Managerial Finance, 35(3), 260-275.

- DeZoort, F.T., Hermanson, D.R., Archambeault D. & Reed, S. (2002). Audit committee effectiveness: A synthesis of the empirical audit committee literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 21, 38-75.

- Donnelly, R. & Mulcahy, M. (2008). Board structure, ownership and voluntary in Ireland. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(5), 416-429.

- Douma, S., George, R. & Kabir, R. (2006). Foreign and domestic ownership, business groups and firm performance: Evidence from a large emerging market. Strategic Management Journal, 27(7), 637-657.

- Edvinson, L. & Malone, M. (1997). Intellectual capital: The proven way to establish your company’s real value by measuring its hidden brain power, Piatkus, London.

- Fama, E.F & Jensen, M.C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301-325.

- Ferreira, M.A. & Matos, P. (2008). The colours of investors' money: The role of institutional investors around the world. Journal of Financial Economics, 88(3), 499-533.

- Goh, W. (2009). Audit committees, boards of directors and remediation of material weaknesses in internal control. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(2), 486-508.

- Guthrie, J. & Petty, R. (2000). Intellectual capital: Australian annual reporting practices. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(2/3).

- Guthrie, J., Cuganesan, S. & Ward, L. (2008). Industry specific social and environmental reporting: The Australian Food and Beverage Industry. Accounting Forum 32, 1-15.

- Guthrie, J., Petty, R. & Yongvanich, K. (2004). Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(2), 282-293.

- Hart, O. (1983). The market as an incentive mechanism. Bell Journal of Economics, 14(2), 336-382.

- Hashim, H.A. & Devi, S.S. (2007). Corporate governance, ownership structure and earnings quality: Malaysian evidence. Research in Accounting and Emerging Economies, 8, 97-123.

- Hermalin, B.E. & Weisbach M.S. (1991). The effects of board composition and direct incentives on firm performance. Financial Management, 20,101-112.

- Hidalgo, R.L., Garc?´a-Meca, E. & Mart?´nez, I. (2011). Corporate governance and intellectual capital disclosure. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 483-495.

- Hill, J.G. (1999). Deconstructing Sunbeam-Contemporary issues in corporate governance. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 67, 1099-1127.

- Ho, S.S.M. & Wong, S.K. (2001). A study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 10(2), 139-156.

- Holland, J. (2003). Intellectual capital and the capital market–organisation and competence. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 16(1), 39-48.

- Holland, J. (2006). Fund management, intellectual capital, intangibles and private disclosure. Managerial Finance, 32(4), 277-316.

- Jaffar, R., Mardinah, D. & Ahmad, A. (2013). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure practices: Evidence from a two tier board systems in Indonesia, Jurnal Pengurusan, 39, 83-92.

- Jensen, M.C. & Meckling, W.H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1992). The balanced scorecard-measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71-79.

- Khanchel, I. (2007). Corporate governance: Measurement and determinant analysis. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(8), 740-760.

- Khodadadi, V., Khazmi, S. & Aflatooni, A. (2010). The effect of corporate governance structure on the extent of voluntary disclosure in Iran. Business Intelligence Journal, 3(2), 151-164.

- Kobeissi, N. & Sun, X. (2010). Ownership Structure and bank performance: Evidence from the Middle East and North Africa region. Comparative Economic Studies, 52(3), 287-323.

- Kochhar, R. & David, P. (1996). Institutional investors and firm innovation: A test of competing hypotheses. Strategic Management Journal, 17(1), 73-84.

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- Krishnan, G.V. & Visvanathan, G. (2008). Does the SOX definition of an accounting expert matter? The association between audit committee directors' accounting expertise and accounting conservatism. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(3), 827-857.

- Kristandl, G. & Bontis, N. (2007). The impact of voluntary disclosure on cost of equity capital estimates in a temporal setting. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8(4), 577-594.

- Lakhal, F. (2005). Voluntary earnings disclosures and corporate governance: Evidence from France. Review of Accounting and Finance, 4(3), 64-85.

- Lara, J.M.G., Osma, B.G. & Penalva, F. (2007). Board of directors' characteristics and conditional accounting conservatism: Spanish evidence. European Accounting Review, 16(4), 727-775.

- Li, J., Mangena, M. & Pike, R. (2012). The effect of audit committee characteristics on intellectual capital disclosure. The British Accounting Review, 44(2), 98-110.

- Li, J., Pike, R. & Haniffa, R. (2008). Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK firms. Accounting and Business Research, 38(2), 137-159.

- Li, X. (2010).The impacts of product market competition on the quantity and quality of voluntary disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies, 1-49.

- Marr, B., Mouritsen, J. & Bukh, P.N. (2003). Perceived Wisdom. Financial Management, July/August, 32.

- Milne, M. & Adler, R. (1999). Exploring the reliability of social and environmental disclosures content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 12(2), 237-256.

- Mustafa, S. & Youssef, N. (2010). Audit committee financial expertise and misappropriation of assets. Managerial Auditing Journal, 25(3), 208-225.

- Naser, K., Al-Hussaini, Al-Kwari, D. & Nuseibah, R. (2006). Determinants of corporate social disclosure in developing countries: The case of Qatar. Advances in International Accounting, 19(6), 1-23.

- Petty. R. & Cuganesan, S. (2005). Voluntary disclosure of intellectual capital by Hong Kong companies: Examining size, industry and growth effects over time. Australian Accounting Review, 15(36), 40-50.

- Ramadan,M. & Majdalany,G. (2013). The impact of corporate governance indicators on intellectual capital disclosure: An empirical analysis from the banking sector in the United Arab Emirates. Proceedings of the International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management & Organizational Learning, 351-361.

- Rashid, A. (2010). The role of institutional investors in the inventory and cash management practices of firms in Asia. Journal of Multinational Financial Management,20(2), 126-143.

- Rediker, K.J. & Seth, A. (1995). Boards of directors and substitution effects of alternative governance mechanisms. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 85-99.

- Ruth, H., Emma, G. & Mart?´nez, I. (2011). Corporate governance and intellectual capital Disclosure. Journal of business ethics, 100(3), 483-495.

- Saha, A.K. & Akter, S. (2013) Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure practices of financial and non-financial sector companies in Bangladesh. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 11(2), 45-61.

- Saleh, N.M., Iskandar, T.M. & Rahmat, M. (2007). Audit committee characteristics and earnings management: Evidence from Malaysia. Asian Review of Accounting, 15(2), 147-163.

- Singh, I. & Van der Zahn, J. (2008). Determinants of intellectual capital disclosure in prospectuses of initial public offerings. Accounting and Business Research, 38(5), 409-431.

- Sullivan, P.H. (2000). Profiting from intellectual capital. Journal of Knowledge Management, 3(2), 132-143.

- Sveiby, K.E. (1997). The intangible assets monitor. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 1, 73-97.

- Tihanyi, L., Johnson, R.A., Hoskisson, R.E. & Hitt, M.A. (2003), Institutional ownership differences and international diversification: The effects of boards of directors and technological opportunity. The Academy of Management Journal, 195-211.

- Unite A. & Sullivan, M. (2003). The effect of foreign entry and ownership structure on the Philippine domestic banking market. Journal of Banking & Finance, 27, 2323-2345.

- Vandemaele, S.N., Vergauwen, P. & Smits, A.J. (2005). Intellectual capital disclosure in the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK: A longitudinal and comparative study. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(3), 417-426.

- Vergauwen, P. & Alem, F.J.C. (2005). Annual report IC disclosures in the Netherlands, France and Germany. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(1), 89-104.

- Ward, A.J., Brown, J.A. & Rodriguez, D. (2009). Governance bundles, firm performance and the substitutability and complementarily of governance mechanisms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(5), 646-660.

- White, G., Lee, A. & Tower, G. (2007). Drivers of voluntary intellectual capital disclosure in listed biotechnology companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8(3), 517-537.

- Williams, S.M. (2001). Are intellectual capital performance and disclosure practices related? Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2(3), 192-203.

- Xie, B., Davidson, W.N. & Dadalt, P.J. (2003). Earnings management and corporate governance: The role of the board and the audit committee. Journal of Corporate Finance, 9(3), 295-316.

- Yi, A. & Davey, H. (2010). Intellectual capital disclosure in Chinese (mainland) companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 11(3), 326-347.

- Zaman, K. M. & Ali, M. (2010). An empirical investigation and users’ perceptions on intellectual capital reporting in banks; Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 14(1), 48-69.

- Zhang, G. (2001). Private information production, public disclosure and the cost of capital: Theory and implication. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18(2), 363-384.