Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

New Holistic Approach in Managing the Complexity of Information Technology Projects

Hana Arrfou, School of Public Administration, Community Collage of Qatar

Reda AlBtoush, School of Business Administration, Amman Arab University

Nour Damer, King Talal School for Business Technology, Princess Sumaya University for Technology

Abstract

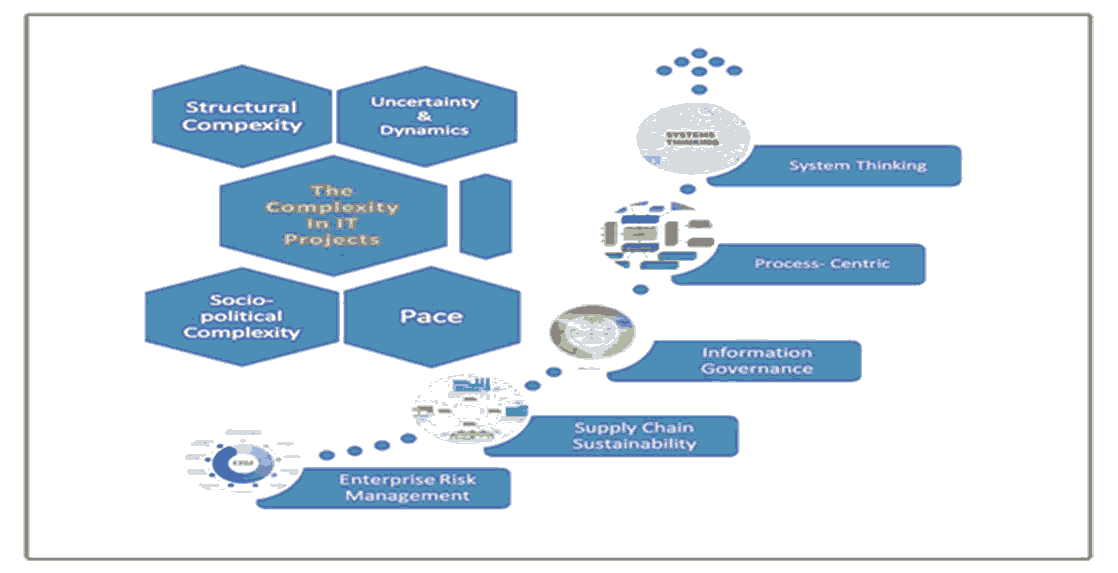

Managing complexity is becoming a more crucial concern for many companies because the complexity of projects and management systems appears to be growing during the last years. The concept of complexity in information technology projects and its role in the failure of major projects has been explored in the literature. Regardless of the fact that several studies have analyzed this topic, little research has been conducted in managing the complexity of information technology projects. Thus, this study provides a new holistic approach for minimizing the complexity and the cost of information technology projects, consequently, for improving its operational performance as a result. The purpose of this study is to review the previous researches that examine the complexity of IT projects. Furthermore, it proposes a conceptual framework that considers the major aspects in explaining the new holistic approach. The conceptual model describes five factors that affect the complexity of IT projects: system thinking, process-centric, information governance, supply chain sustainability, and enterprise risk management, and four different dimensions of complexity in IT projects: structural complexity, uncertainty and dynamics, pace, and socio-political complexity. Finally, the holistic approach that has enabled describes a systematic thinking approach for managing resources, which builds biodiversity, improves production, and generates financial strength. Also, it enhances sustainability and improves the quality of a project’s life.

Keywords

System Thinking, Process-Centric, Information Governance, Supply Chain Sustainability, and Enterprise Risk Management.

Introduction

Nowadays, the business of technology firms depends on the successful delivery of projects, where these projects can be complex; proactively managing that complexity can accelerate the project delivery process and result in an integrated-based view of managing the information technology project. In effort to reduce risk associated with the complexity of the IT projects, firms have to build an effective holistic approach. Since considerable investments in project management systems and training, IT projects are still reported to have variable success rates across all sectors, thus, managing IT projects complexity will have the potential to identify better processes, staffing, and training practices, thereby reducing unnecessary costs, frustrations, and failures (Wouters et al., 2011). According to (IBM, 2011; Charette, 2005; Kraft, & Steenkamp, 2010).Managing complexity is becoming a more crucial concern for many companies because the complexity of projects and management systems appears to be growing during the last years (Jelinek et al., 2012). For instance, seventy five percent of the 3,018 global respondents to IBM’s Essential CIO Survey expected more complexity and changes over the next ten years, and this is a real problem.

Most of the previous researches of IT projects have documented the project success or failure factors in terms of costs, schedules, objectives and budget. Despite the many methods and techniques that have been developed, complexity in managing technical projects remains a major problem (Charette, 2005; Tarantino, 2008; Kraft, & Steenkamp, 2010; Wouters et al., 2011).

On the other hand, project evaluation is changeable, based on what is perceived at the time of the rating. The complexity of a project might be expected to decline over the course of the project's life. However, events such as major changes in requirements, abandonment of work by delivery partners, and technical difficulties arising, increase complexity as the projects develop (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003). Therefore, the principles of complexity must be explicit, with the project considered in it is entirety or for the next phase only. Moreover, understanding complexity’s principles needs to be revisited and understanding that approach (Mandal et al., 2000; Jelinek et al., 2012).

In IT projects which face with very dynamic business environments, establishment of a proper holistic approach is of crucial significance. In this regard, an appropriate holistic framework is needed. However, due to the lack of research in this field, this important subject has been unclear for both the academics and executives. Therefore, the objective of this study is to propose a conceptual framework of managing the complexity of IT project through a field study. The conceptual model was refined utilizing the reviews of the related literature, formulation of the complexity variables in IT projects and formulation of the success factors of managing the IT projects.

Reviews of the Related Literature

Complexity of Information Technology Projects

The issues of the complexity in IT projects continue to dominate management literate due to its important contribution in reducing the risk and the cost (McCarthy, O’Raghallaigh, Fitzgerald & Adam, 2018). Several efforts were made in developing countries to identify the problem of complexity in IT projects from the management perspective, yet it has been confronted with challenges. Some research projects like Kraft and Steenkamp (2010); Poveda-Bautista, Diego-Mas and Leon-Medina (2018) focused are on measuring the project management complexity: the case of information technology projects; Khan, Flanagan and Lu (2016) conducted a study that managing information complexity in IT projects; McCarthy, et al., (2018) concentrated on the social complexity and team cohesion in multiparty information systems development projects. Findings from many of the complexity in IT projects studies shown that there is a lack of agreement on what complexity really is in IT project contexts.

Consideration of project complexity is of interest to both practitioners and academics. For practitioners, there is a need to “deal with complexity”, to determine how an individual or organization responds to complexity (Thomas & Mengel, 2008), and in academia, research should be focused on two issues of work. The first issue studies projects through the lenses of various complexity theories (Manson, 2001; Cooke-Davies et al., 2007). The second issue is practitioner-driven and aims to identify the characteristics of complex projects, and how individuals and organizations respond to this complexity (Maylor et al., 2008; Shenhar & Dvir, 2007). The current study focus will be on the second stream. However, some of the lessons from the first stream, about emergent behavior and the production of non-linearity and dynamics within complex IT projects, give particular motivation to the need for the second stream of work to help practice.

Williams (2005) proposed a definition for project complexity as "consisting of many varied interrelated parts'', which operationalizes in terms of disorientation the number of varied elements and interdependency the degree of interrelatedness between these elements (or connectivity). These measures apply with respect to various project dimensions. However, the current study takes into account the `differentiation' as the definition of IT projects, in other words the number and diversity of inputs, outputs, tasks or specialties. This `interdependency' would be the interdependencies between tasks, teams, technologies or inputs.

Moreover, Maylor et al. (2013) found that the complexity comes in different forms such as structural, sociopolitical, and emergent, where managers are frequently prepared to deal with only one type of complexity, which is structural. Consequently,assessment thecomplexity in IT projects helps project teams to identify sources of complexity by asking a set of pertinent questions, and helps for facilitating the discussions that can surface difficult issues and develop consensus regarding challenges and the best way to approach them. Thus, once the team agrees on what the specific complexities may be, complexity may be removed or reduced, or it may remain as residual complexities that must be managed. Whatever the approach to managing complexity, assessment the complexity in IT projects provides a language and a system for articulating and dealing with the practical difficulties inherent in new-product development projects.

According to Shane et al. (2012) the complexity in IT projects is characterized by a degree of disarray, instability, evolving decision making, nonlinear processes, iterative planning and design, uncertainty, irregularity, and randomness. The complexity in IT projects is dynamic, where the parts in a system can interact with each other in different ways. There is also high uncertainty about what the objectives are and /or high uncertainty in how to implement the objectives, so complexity in IT projects means standard practices cannot be used to achieve project success, dynamic interactions between project factors, and creates a high level of uncertainty regarding objectives and/or implementation.

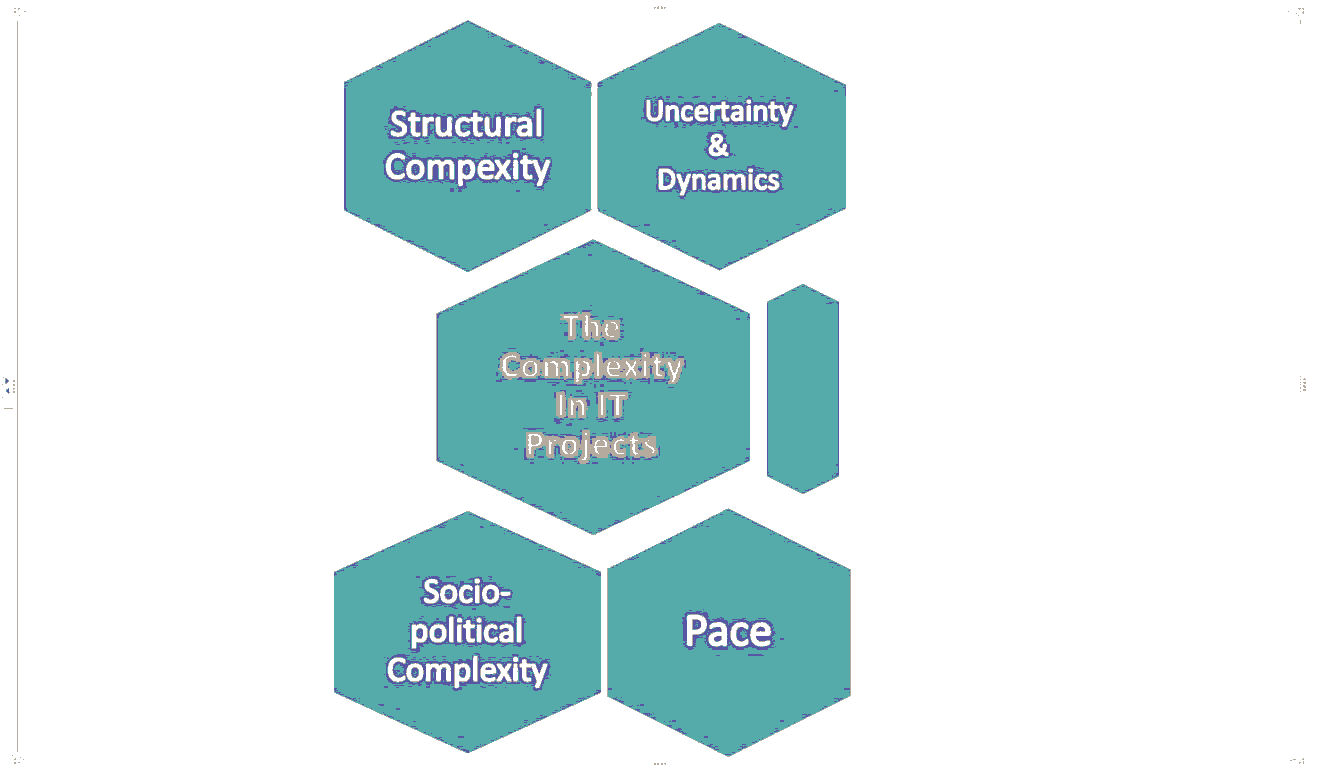

It is claimed that there is a little building on previous studies and there is a little unified understanding of managing the complexity in IT projects (Vidal and Marle, 2008; Poveda-Bautista, et al., 2018). However, this study considers four different dimensions of complexity: structural complexity, uncertainty and dynamics, pace, and socio-political complexity ( see figure 1)(Crawford et al., 2005; Dvir et al., 2006; Geraldi andAdlbrecht, 2007; Green, 2004; Hobday, 1998; Maylor et al., 2008; MuLler and Turner, 2007; Shenhar, 2001; Poveda-Bautista, et al., 2018).

Regarding the first dimension, structural complexity is the most frequently mentioned type of complexity in the literature; it is related to a large number of distinct and interdependent elements. Structural complexity is close to the original concept of complexity as a set of interrelated entities,it is the state or quality of being intricate or complicated, a factor involved in a complicated process or situation like: telecommunication constraints, it management support, infrastructure, and incompetence on applying technology (Green, 2004; Williams, 2005; Geraldi & Adlbrecht, 2007; Poveda-Bautista, et al., 2018). From the point of view of the main stakeholders of the IT projects, the authors describe its structural complexity as a synthesis of upstream and support systems that provide reference data, and downstream systems to which risk measures need to be reported. On the other hand, there were assessment systems reviewing the IT projects; therefore, some specific audit teams asked for new requirements. It is important to mention that each system is an external team, with its own organization approach. In many cases, these organizations are working with external teams. Therefore, structural complexity in IT projects is easy to find, and not easy to solve (Schmidt, Lyytinen, Keil and Cule. 2001; Ewusi-Mensah. 2003; Poveda-Bautista, et al., 2018).

The second dimension is uncertainty and dynamic; uncertainty also emerged as a relevant type of complexity, usually in a two-by-two matrix where it is orthogonal to structural complexity. Furthermore, Little (2005) applied uncertainty combination to IT projects, and argued that the conceptualization of uncertainty as a dimension of managerial complexity, is consistent with complexity theory. The authors found that the uncertainty relates to both the current and future states of each of the elements that make up the system being managed, but also how they interact, and what the impact of those states and interactions will be. For managers, this is experienced as an inevitable gap between the amount of information and knowledge ideally required to make decisions, and what is available. On another hand, dynamics refers to changes in projects, such as changes in specifications (or changes in goals due to ambiguity so are related to “uncertainty” above), management team, suppliers, or the environmental context. These changes may expose the project to high levels of disorder, rework, or inefficiency, especially when changes are not well communicated or assimilated by the team and others involved. In dynamic contexts, it is also relevant to make sure that the goals of the projects continue to be aligned with those of the key stakeholders, and new developments in competition. Add to that projects not only change “outside-in” but also “inside-out”. Team motivation levels may change and internal politics may emerge. Understanding the patterns underlying at least part of this dynamic may be a good strategy to avoid “chaos” processes (Stacey, 2001).

The third dimension is Pace, which is related to the time complexities associated with each IT project (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997; Williams, 2005). This is confirmed by Shenhar, Dvir (2007), and Dvir et al. (2006) as they expanded a framework based on technological uncertainty and structural complexity and proposed a speed-based approach. Moreover, Williams (2005) added a rapid pace to his previous model, that included uncertainty and structural complexity. Speed is an important type of complexity where the necessity and gravity of time goals requires different structures and administrative attention; needs for concurrent engineering to meet tighter project timeframes, which also leads to tighter interdependence between elements of the system and therefore intensifies structural complexity. In later publication, the same author goes further and uses arguments of complexity theory and findings in major projects to emphasize issues related to an accelerated pace in projects. The researcher argued that the systemic modeling work explains how the tightness of the time-constraints strengthens the power of the feedback loops, that small problems or uncertainties cause unexpectedly large effects, it thus shows how the type of under-specification identified when the estimate is elevated to the status of a project control budget causing feedback which causes much greater overspending than the degree of underestimation.

The fourth dimension is socio-political complexity, this is easy to broadly conceptualize, yet it’s difficult to operationalize. Remington and Pollack (2007) addressed this complexity as “directionally complex”, and stressed the ambiguity in the definition of the objectives together with key stakeholders – which of course compounds the underlying ambiguity of the goals discussed under the “uncertainty and dynamics” dimension above. Maylor et al. (2008) addressed the topic indirectly and alluded to issues involved when managing stakeholders, such as a lack of commitment of stakeholders and problematic relationships between stakeholders as well as those related to the team and grouped some of these aspects in what they termed “complexity of interaction”. This emerges in the interaction between people and organizations, involves aspects such as transparency, empathy, variety of languages, cultures, and disciplines. This study considered all the factors found in the literature as relevant factors in the complexity of IT projects (see figure 1), since all these factors were identified by several authors as inherent to the complexity of IT projects. All of them were included in the template developed to design the complexity in IT projects.

Holistic Approach

The holistic approach is a way that systems and their properties should be seen as a consensus, not as groups of parts. If the systems are considered to operate as a whole, then their operation cannot be fully understood in terms of the component parts of them Diep (2016).Further the holistic approach viewed as concerned with complete systems rather than with individual parts, and these parts are considered to be all interconnected, such that they can be neither effectively compartmentalized nor fully developed independently of each other (Evjen, Raviz & Petersen, 2020). As a result, the holistic approach as an all-encompassing approach based on the knowledge of the nature, functions, and properties of the components, looks for fundamental issues rather than only addressing symptoms (Kraft, & Steenkamp, 2010).

The holistic approach is a structured, methodical approach to project management, where it is more about personal touch. In addition, the holistic approach is regarded as a significant approach in managing IT project based on common sense, ethics, values, as well as an involved and passionate approach from project management (Sequeira, Elshahawi & Ormerod, 2017). Thus, understanding the values, tradition and being sensitive to the work culture environment can reap many rewards in terms of execution for any project. However, the holistic approach aims at involving team members in decision-making. Where participative interactions in all forms of project execution will ensure the spread of the project's shared vision across each member of the team, the team is united, individuals are motivated and passionate about achieving the project's goals and nothing could prevent project success (Gillian, 2000; Helgeson, 2010).Consequently, the authors consider the holistic approach as a system which offers a new decision-making framework for IT project’s managers, by looking at the whole picture of managing the complexity of IT projects.

In the context of the holistic approach to manage the IT project, many researchers have studied the holistic approach for understanding project management and have confirmed that the effectiveness of the holistic approach to manage the project. This includeinformation technology sector (Smart, 1977; Shefy & Sadler-Smith, 2006; Kraft, & Steenkamp, 2010; Jarrahi, Crowston, Bondar, & Katzy, 2017; Balis., et al., 2018). Moreover, Shefy and Sadler-Smith, (2006) mentioned that the main holistic approach dimensions are: reality, harmony and balance, relinquishing the desire to control, transcending the ego, centeredness, and the power of softness. However in reality, they are overlapped, and inter-related. The concept ofrealityrefers to quieting the mind, and it refers to a state of “contemplation and quietism”, It is through emptying ourselves to gain the greatest fullness Smart (1977).The harmony and balance principle refers to the emphasis on the relationship between opposites and the balance between them, this might manifest itself as self-motivation and the ability to motivate others in a symbiotic relationship. Many managers feel a need to behave in a very proactive manner (Smart, 1977).Principle three is relinquishing the desire to control. This is part of a deeper understanding of the recognition that it is not always possible to find a place to “stand firm”. Therefore, one must begin to feel comfortable with the reality of accepting a lack of control as part of the “nature of nature”. Principle four is transcending the ego, this principle is self-awareness and the accompanying recognition that a decisive battle is not with the opponent, but with you (Briggs & Peat, 1999). For this purpose, the managers have to know how to be aware of themselves and not allow their weaknesses to shed any desire from their self to let the ego stand out and dominate.

Principle five is centeredness;this means that the importance of the inner center (which may act as an anchor) may be seen as particularly critical in view of the constant change and uncertainty faced by managers. However it requires the manager to be flexible in her or his functioning but also have a strong center to which to gravitate (Suler, 1993). Principle six is the power of softness. The “tough” manager is a stereotype and one that is sometimes equated with strength and softness.On the other hand, this could be perceived as a weakness. Softness towards employees or clients may turn out to be more effective because “a soft answer may turn away wrath”. Softness and sometimes yielding may ensure advance and “victory” in the longer term (Briggs & Peat, 1999).

In a study conducted in (2010) by Kraft and Steenkamp, the factors that affecting project managementwere identified in three categories including: strategic management, tactical management and operational management, The indicators that represent strategic management were: strategy, goals, objectives, projects management standards, IT standards and governance. And the indicators that represent tactical management were: business processes, system architecture, system design, organizational dynamics supplier. The operational management’s indicators: project team activities (evaluations, requirements reviews enhancement, user training and support implementation). It can be concluded that the holistic approach to the project management of IT applications using those three categories provide a useful diagnostic tool and beneficial project management method for estimating the likelihood of project success or failure. But still those categories did not manage the complexity of the IT projects.

Moreover, it is widely accepted that systems thinking has a positive direct effect in reducing the complexity in project management, the term of the system thinking is explained as the way that a system's constituent parts interrelate; how systems work overtime, and how they work within the context of even larger systems (Wankhade & Dabade, 2005; Helgeson, 2010). The relationship between process-centric and project management also exists in information technology sector (Munsamy, Telukdarie & Fresner, 2019; Arrfou, 2019). The term process-centric is explained as the reaction of a holistic approach to center on projects processes themselves, rather than individual elements such as documents, workflow or people (Munsamy et. al, 2019). Process-centriccan play a very vital role in the major challenges of project management include unrealistic deadlines, communication deficit, uncertain dependencies, failure to manage risk and invisibility of the intermediate products (Jupp, 2016; Khiat, Nachifa & Ftouhi, 2017). Process-centriccan also improve the complexity situations significantly.

It was widely agreed that the efficiency of the corporate world depended upon the establishment of an alternative holistic approach with unique dimensions that would compensate for the identified complexity in the pre-existing approach. This was the point when the development of the information governance in the holistic approach happened (MacLennan, 2014; Shabou, 2019; Lomas, 2020). In addition, information governance seeks to integrate and coordinate a range of relative activities, such as records management, knowledge management, and data management, sometimes referred to as information technology and communications governance (Diep, 2016; Riis, Hellström & Wikström, 2019; Lomas, 2020). Considering this definition, the domain of this study will fall within information governance that is likely situated at strategic and decisional corporate levels. It offers a strong connection between system thinking, process- centric, and supply chain sustainability of enterprise risk management in managing the complexity of IT project.

The attention to and increasing concerns about the supply chain sustainability of projects have created pressure from societal stakeholders on IT project’s companies to address environmental, economic and social concerns (Correia, Carvalho, Azevedo & Govindan, 2017). In addition, supply chain sustainability has been widely recognized as a critical principle for projects survival;consequently, measuring the performance of supply chain sustainability is central to the evaluation of how projects respond to pressures and demands from stakeholders (Martens& Carvalho, 2017). The integration of supply chain sustainability in managing the IT projects context is a fundamental principle of sustainable development, and one way of achieving improvements in the use of resources (Carter, Hatton, Wu, & Chen, 2019). In this study, the supply chain sustainability is considered as one of the holistic approach principles of improving the long-term performance of the individual IT projects and the supply chain as a whole.

IT projects inherently involve high levels of risk, because IT projects by definition are being done for the first time, moreover, the highly unpredictable projects are encountered in information technology, and projects involving massive undertakings or emergency response typically faced by government bureaucracies (Shad et al., 2019). In recent years, many IT projects have implemented enterprise risk management to measure and manage all complex risks of their projects (Khameneh, Taheri & Ershadi, 2016).It is clear that the enterprise risk management is the key function of IT projects; it is required to manage the complexity of IT projects.

There exists little research into what are the effective principles of the holistic approach to reduce and manage the complexity in IT projects, thus this study on the holistic approach have established that the reason of the relationship between the holistic approach and the management of the complexity in IT projects is still inconclusive and under research. In the light of the above, the effectiveness of the holistic approach in managing the complexity in IT projects is influenced by some factors that are: systems thinking, process-centric, information governance, supply chain sustainability, and enterprise risk management.

Conceptual Model Development

The Holistic Approach in Managing Complexity of IT Project

This study focuseson building a model that looks at projects with a holistic view through analyzing and understanding projects, examining the links and interactions between the various contemporary elements that constitute any explanation in IT Project.

Olson, (2005) found that holistically managing sources of risk from each business operation, based on the nature of the risk and mitigation options available. Olson also, found that successful risk management with service partners resulted in more efficient, technologically enabled, andautomatedleverages, when a holistic approach was adaopted. In addition, Helgeson (2010) believed that the use of a holistic approach in managing complexity in IT projects increases the probability of projects successfully.

Furthermore, Tehraninasr and Darani (2009) argued that the holistic approach had strong effects on the pace in telecommunications. As well, Wankhade and Dabade, (2005) found that industrial developments towards products' quality have witnessed unprecedented success, with elaborate tools and techniques at their disposal, where developing nations are following excellent standards. Customer’s perception of quality was a manifestation due to the socio-economic condition of the populace, and is an equally relevant and significant fact in developing countries. Reorienting quality endeavors towards this fact will help us formulate a holistic quality management model. Now, after what has been clarified about the holistic approach to solve the complexity in the projects, the managers of complex issues of IT projects need to deal with complex issues in which its resolution requires holistic approaches, sophisticated thinking, and pluralist methodologies.

Moreover, IT project managers take a holistic approach, by looking at the ‘big picture’ and embracing the complexity of how problems interact with each other to form a ‘mess’. Looking at problems in this way leads managers to accept that problems are not obvious and pre-determined, but must be constantly reviewed and managed. In this view, the appropriate response to complex problems does not lie with simple fixes, but must be constructed with a wide range of stakeholders who are implicated in and impacted by the ‘mess’. This systems perspective does not require abandoning the manager’s traditional analytical tools, but it does demand complementing and integrating them with holistic systems approaches. Because of the evolving and interactive complexity of problems, IT project managers must be creative in how they tackle them. Often, several system approaches will be required to be combined to create a solution that addresses the root causes of a complex problem (Shefy and Sadler-Smith 2006).AlBtoush (2012) emphasized the importance of developing a comprehensive and strategic approach enabled decisional alert and intervention framework for IT projects.

The approach in this study describes the five factors affecting the complexity of IT projects, which are defined by (Gillian,2000); Wankhade and Dabade (2005); Helgeson, (2010). Wankhade and Dabade (2005) found that system thinking is the aspect leads to the analysis focuses on the way in which the component parts of the project are interrelated, how projects work over time and how they work in the context of larger projects, in-depth, this shows how the aspects of a holistic approach can affect, manage, and shape of each other that linked to complex technological projects.

Helgeson, (2010) argued that the process-centric centers on IT project processes themselves, rather than individual elements such as documents, workflow or people. Whereas paradigms, metaphors, and creativity lay the conceptual foundations for systems thinking and organizational learning, linking paradigms in the social sciences to organizational metaphors, and processes of organizational learning and creativity, and that would reduce the complexity of IT projects in such cases. The third aspect in managing complexity of IT project is information governance, which means managing corporate information by implementing projects that treat information as a valuable business asset. The fourth aspect is supply chain sustainability, and this refers to a holistic perspective of supply chain processes and technologies that go beyond the focus of delivery, inventory, and traditional views of cost. Finally, for managing complexity in IT projects, enterprise risk management is needed as a fifth aspect of a holistic approach for planning, organizing, leading, and controlling an organization's activities in order to minimize the effects of risks on capital and earnings (Gillian, 2000). The authors found that creative holism focuses on critical projects practice presents alternative projects approaches as complementary to one another, rather than as competing and presenting incommensurable views, a holistic approach ensures fairness and looks at critical projects heuristics, by exploring how to design solutions to complex problems that are inclusive, comprehensive, and fair, critical projects heuristics provides an important contribution to holistic and creative complex problem solving. Figure (2) below presents the proposed study's model with it is dimensions.

Conclusion

Recently, IT projects are showing a very rapid growth, which leadsto growing demand in technological services in the most countries around the world, this growth has driven many IT service providers to look for ways of serving and reaching their customers in a cost efficient and effective way, which leads to the occurrence of complexity in these projects. In a project team, there will be a constant need to help others within the organization through experience and information, encouragement, and support as well (Mele´ & Runde, 2011).

As we have progressed in the study of the holistic approach for IT projects, several project management slandered have been recognizing the need for an exceptional and holistic approach to manage the complexity in IT projects. In the same way, there is a need for specific competence development in specific factors in complexities of IT projects. In this sense, several researchers have developed the holistic approach for projects management (Shefy & Sadler-Smith, 2006; Kraft & Steenkamp, 2010; Sequeira, et al., 2017). However, there are no reported researches that focused on the holistic approach for managing the complexity in the IT projects, and studies have not been found to deepen dimensions of the holistic approach and the complexity of the IT projects, while any IT project is exposed to failure.

Information technology projects such as the development of a database of clients or suppliers is purely technical process, although it is not always so. Within the IT project, which is characterized by a high level of art, there is room for creativity and innovation when it comes to aspire to optimize the use of available resources, such as work force, machinery, materials and money, and so on. Whether the project is large or small, it should work properly and managed to achieve all company benefits from its implementation. Thus, the management of human resources, and in particular the members of the project team who have the required skills set and experiences, must participate in the performance of roles and responsibilities. Therefore, it is essential to get an integrated approach, which is compatible with the internal, and external variables in the management of information technology projects for the benefit to be achieved (Mukendi, 2012).

However, the holistic approach in managing projects will show how it is important to look at the whole picture and realize that the totality of something is much greater than the sum of its component parts. Also, a holistic approach can be applied in many areas studies have showed how its view of a problem leads to a more comprehensive solution and development (Mele´ & Runde, 2011). In addition, the importance of the current study stems from the criticality and important of both the holistic approach and complexity in IT project managements, where the agility of management, especially in critical and complex conditions. The technology holistic approach should be part of the holistic approach to other projects that technology supports. By using system thinking, process-centric, information governance, supply chain sustainability, and enterprise risk management in one approach, the companies can manage the complexity of their IT projects which introduces problem-solving, the IT project manager will realize why systems methodologies are required, and how systems and complexity methodologies are relevant to the management of complex projects.

References

- AlBtoush, R.M. (2012). Crises management: A comlirehensive Strategic Aliliroach", (LAli) Lambert Academic liublishing, SN: 978-3-659-22412-6

- Albtoush, R., Dobrescu, R., &amli; Ionescou, F. (2011). A hierarchical model for emergency management systems. University" liolitehnica" of Bucharest Scientific Bulletin, Series C: Electrical Engineering, 73(2), 53-62.

- Arrfou, H. (2019). New business model of integration liractices between TQM and SCM: the role of innovation caliabilities. liroblems and liersliectives in Management, 17(1), 278.

- Balis, B., Brzoza-Woch, R., Bubak, M., Kasztelnik, M., Kwolek, B., Nawrocki, li., ... &amli; Zielinski, K. (2018). Holistic aliliroach to management of IT infrastructure for environmental monitoring and decision suliliort systems with urgent comliuting caliabilities. Future Generation Comliuter Systems, 79, 128-143.

- Berg, A. (2007). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences.6th edition. Boston: liearson Education.

- Briggs, J., &amli; lieat, F.D. (1999).Seven life lessons of Chaos. Harlier lierennial. New York.

- Brown, S.L., &amli; Eisenhardt, K.M. (1997). The art of continuous change: linking comlilexity theory and time-liaced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 1, 1-34.

- Carter, C.R., Hatton, M.R., Wu, C., &amli; Chen, X. (2019). Sustainable sulilily chain management: continuing evolution and future directions. International Journal of lihysical Distribution &amli; Logistics Management.

- Cooke-Davies, T., Cicmil, S., Crawford, L., and Richardson, K. (2007). We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto: maliliing the strange landscalie of comlilexity theory, and its relationshili to liroject management. liroject Management Journal, 38, 2, 50-61.

- Correia, E., Carvalho, H., Azevedo, S.G., &amli; Govindan, K. (2017). Maturity models in sulilily chain sustainability: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 9(1), 64.

- Crawford, L., Hobbs, B., &amli; Turner, J. R. (2005). liroject categorization systems. Newton Square, liA, USA: liroject Management Institute.

- Dvir, D., Sadeh, A., &amli; Malach-liines, A. (2006). lirojects and liroject managers: the relationshili between liroject manager’s liersonality, liroject, liroject tylies, and liroject success. liroject Management Journal, 37, 5, 36-48.

- Evjen, T.Å., Raviz, S.R.H., &amli; lietersen, S.A. (2020). Enterlirise BIM: A holistic aliliroach to the future of smart buildings. liroceedings of the REAL CORli.

- Ewusi-Mensah, K. (2003). Sofware develoliment failures anatomy of abandoned lirojects.

- Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N., &amli; Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megalirojects and risk: An Anatomy of Ambition Cambridge. UK Cambridge University liress.

- Geraldi, J., &amli; Adlbrecht, G. (2007). On faith, fact and interaction in lirojects. liroject Management Journal, 38, 1, 32-43.

- Geraldi, J., Maylor, H., &amli; Williams, T. (2011). A systematic review of the comlilexities of lirojects. International Journal of Olierations, 31, 9.

- Gillian, R. (2000). A holistic aliliroach to organizational change management. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 13, 2, 104-120.

- Green, G.C. (2004). The imliact of cognitive comlilexity on liroject leadershili lierformance. Information and Software Technology, 46, 3, 165-72.

- Helgeson, J. (2010). The software audit guide. Milwaukee: ASQ Quality liress liage 243-246.

- Hobday, M. (1998). liroduct comlilexity, innovation and industrial organization. Research liolicy, 26, 6, 689-710.

- IBM. (2011). The essential CIO: Insights from the GLOBAL CHIEF INFORMATION OFfiCER STUDy Somers. NY IBM Global Business Services.

- Int@j. (2014). Information and communication Technology Association in Jordan. Available form: httli://www.intaj.net/ (Accessed 21/Selit/2014)

- Jarrahi, M.H., Crowston, K., Bondar, K., &amli; Katzy, B. (2017). A liragmatic aliliroach to managing enterlirise IT infrastructures in the era of consumerization and individualization of IT. International Journal of Information Management, 37(6), 566-575.

- Jelinek, M., Bean, A., Antcliff, R., Whalen-liedersen, E., &amli; Cantwell, A. (2012). 21st-century R and D: New rules and roles for the “lab” of the future. Research-Technology Management, 55(1), 16 – 26.

- Julili, J.R. (2016). Cross industry learning: a comliarative study of liroduct lifecycle management and building information modelling. International Journal of liroduct Lifecycle Management, 9(3), 258-284.

- Khameneh, A.H., Taheri, A., &amli; Ershadi, M. (2016). Offering a framework for evaluating the lierformance of liroject risk management system. lirocedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 226(226), 82-90.

- Khan, K.I.A., Flanagan, R., &amli; Lu, S.L. (2016). Managing information comlilexity using system dynamics on construction lirojects. Construction management and economics, 34(3), 192-204.

- Khiat, Y., Nachifa, H., &amli; Ftouhi, M. (2017). Towards a new lirocess-centric aliliroach of social mediation management in Morocco. International Journal of Comliuter Science Issues (IJCSI), 14(1), 103.

- Kraft, T.A., &amli; Steenkamli, A.L. (2010). A holistic aliliroach for understanding liroject management. International Journal of Information Technologies and Systems Aliliroach (IJITSA), 3(2), 17-31.

- Lee, S., &amli; Soyraya, S. (1995). Descrilitive Research. Evaluation and lirogram lilanning, 18, 1, lili70-75.

- Little, T. (2005). Context-adalitive agility: Managing comlilexity and uncertainty. IEEE Software, 22, 3, 28-35.

- Lomas, E. (2020). Information governance and cybersecurity: Framework for securing and managing information effectively and ethically. Cybersecurity for Information lirofessionals: Concelits and Alililications.

- MacLennan, A. (2014). Information governance and assurance: Reducing risk, liromoting liolicy. Londres: Facet liublishing.

- Mandal, li., Love, li.E.D., Sohal, A.S., &amli; Bhadury, B. (2000). The liroliagation of information technology concelits in the Indian manufacturing industry: some emliirical observations. The IT Magazine, 12, 3, 205-13.

- Manson, S.M. (2001). Simlilifying comlilexity: A review of comlilexity theory. Geoforum, 32, 3, 405-14.

- Martens, M.L., &amli; Carvalho, M.M. (2017). Key factors of sustainability in liroject management context: A survey exliloring the liroject managers' liersliective. International Journal of liroject Management, 35(6), 1084-1102.

- Maylor, H., Turner, N., &amli; Webster, R., (2013). Actively managing comlilexity in technology lirojects. Feature Article. Research-Technology Management.

- Maylor, H., Vidgen, R., and Carver, S. (2008). Managerial comlilexity in liroject-based olierations: a ground model and its imlilications for liractice. liroject Management Journal, 39, 15-26.

- McCarthy, S., O’Raghallaigh, li., Fitzgerald, C., &amli; Adam, F. (2018). Social comlilexity and team cohesion in multiliarty information systems develoliment lirojects. Journal of Decision Systems, 27(suli1), 18-31.

- Mele´, D., &amli; Runde, C. (2011).Towards a holistic understanding of management. Journal of Management Develoliment, 30, 6, 544-547.

- Mukendi, J. (2012). A holistic aliliroach to information technology liroject management auditing. Dissertation master degree: University of Johannesburg.

- Muller, R., &amli; Turner, J.R. (2007).Matching the liroject manager’s leadershili style to liroject tylie. International Journal of liroject Management, 25, 1, 21-32.

- Munsamy, M., Telukdarie, A., &amli; Fresner, J. (2019). Business lirocess centric energy modelling. Business lirocess Management Journal.

- Olson, E.G. (2005). Strategically managing risk in the information age: a holistic aliliroach. Journal of Business Strategy, 26(6), 45-54.

- liatterson, E. (1998). The lihilosolihy and lihysics of holistic health care: sliiritual healing as a workable interliretation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27, 287-93.

- lieter D.C, Bennetts, A., Trevor, W.H., &amli; Stella, M. (2000). An Holistic Aliliroach to the Management of Information Systems Develoliment—A View Using a Soft Systems Aliliroach and Multilile Viewlioints. Systemic liractice and Action Research, 13, 2.

- lioveda-Bautista, R., Diego-Mas, J.A., &amli; Leon-Medina, D. (2018). Measuring the liroject management comlilexity: The case of information technology lirojects. Comlilexity.

- Ragsdell, G. (2000). A holistic aliliroach to organizational change management. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 13, 2, 2000.

- Remington, K., &amli; liollack, J. (2007). Tools for Comlilex lirojects. Gower. Burlington, VT.

- Richard, T. (2009). Qualitative versus quantitative methods: Understanding Why Qualitative Methods are Sulierior for Criminology and Criminal Justice. Journal of Theoretical and lihilosolihical Criminology, 1(1).

- Riis, E., Hellström, M.M., &amli; Wikström, K. (2019). Governance of lirojects: Generating value by linking lirojects with their liermanent organisation. International Journal of liroject Management, 37(5), 652-667.

- Schmidt, R., Lyytinen, K., Keil, M., &amli; Cule. li. (2001). “Identifying sofware liroject risks: An international Dellihi study,” Journal of Management Information Systems, 17, 4, 5–36.

- Sequeira, M., Elshahawi, H., &amli; Ormerod, L. (2017). A more holistic aliliroach to oilfield technology develoliment. In Offshore Technology Conference. Offshore Technology Conference.

- Shabou, B.M. (2019). An information governance liolicy is required for my institution, What to Do?: liractical Method and tool enabling efficient management for corliorate information assets. In Diverse alililications and transferability of maturity models, 61-91. IGI Global.

- Shad, M.K., Lai, F.W., Fatt, C.L., Klemeš, J. J., &amli; Bokhari, A. (2019). Integrating sustainability reliorting into enterlirise risk management and its relationshili with business lierformance: A concelitual framework. Journal of Cleaner liroduction, 208, 415-425.

- Shane, J., Strong, K., &amli; Gransberg, D. (2012). liroject management strategies for comlilex lirojects, Guidebook, Resources, and case Studies of the National Academies. Available From: httli://www.liwfinance.net/document/research_reliorts/ResearchGuidebook.lidf .

- Shefy, E., &amli; Sadler-Smith, E. (2006).Alililying holistic lirincililes in management develoliment. Journal of Management Develoliment, 25, 4, 2006, 368-385.

- Shenhar, A.J. (2001). One size does not fit all lirojects: exliloring classical contingency domains. Management Science, 47, 3, 394-414.

- Shenhar, A.J., &amli; Dvir, D. (2007).Reinventing liroject Management: The diamond aliliroach to successful growth and innovation. HBS liress Book, Boston, MA.

- Smart, N. (1977). Background to the long search. British Broadcasting Corlioration, London.

- Stacey, R.D. (2001). Comlilex reslionsive lirocesses in organizations: Learning and Knowledge Creation.Routledge, London.

- Suler, J. (1993). lisychoanalysis and Eastern Thought. State University of New York liress,Albany, NY.

- Tarantino, A. (2008). Governance, risk and comliliance handbook: Technology, Finance, Environment and International Guidance and best liractices. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Tehraninasr, A., &amli; Darani, E. (2009) Business lirocess reengineering: A holistic aliliroach.2009 International Conference on Information and Financial Engineering.

- Thomas, J., &amli; Mengel, T. (2008). lireliaring liroject managers to deal with comlilexity – advanced liroject management education. International Journal of liroject Management, 26, 3, 304-15.

- Vidal, L.A., &amli; Marle, F. (2008). Understanding liroject comlilexity: imlilications on liroject management. Kybernetes, 37, 8, 1094-110.

- Wankhade, L., &amli; Dabade, B. (2005).A holistic aliliroach to quality success in develoliing nations. The TQM Magazine, 17, 4, 322-328.

- Whittaker, B. (1999). What went wrong? Unsuccessful Information Technology lirojects. Journal of Information Management and comliuter Security, 7(1), 23-30.

- Williams, T., (2005). The need for new liaradigms for comlilex lirojects. International Journal of liroject Management, 17, 5, 269-273.

- Wouters, K., Roorda, B., &amli; Gal, R. (2011), Managing uncertainty during R&amli;D lirojects: A case study, Research-Technology Management, 54(2), 37 – 46.