Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 6S

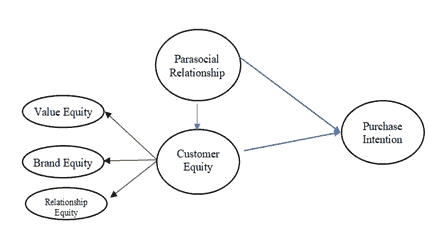

Parasocial relationship, customer equity, and purchase intention

Asty Almaida, University of Hasanuddin

Wahda, University of Hasanuddin

Isnawati Osman, University of Hasanuddin

Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of Parasocial Relationship (PSR) in the relation between Generation Z with social media influencers and its impacts on customer equity and purchase intention. An online survey was conducted on 200 Gen Z in Makassar city and the data obtained were analyzed using a Structural Equation Model with PLS software. The results show that PSR, Social Media Influencers, and Gen Z positively impact customer equity and purchase intention. Specifically, customer equity influences purchase intention more significantly than PSR. Furthermore, it has a positive and significant role as mediating variable in the relationship between PSR and purchase intention. Due to the importance of the purchasing decision process on organizational performance and the need for policies in determining the right marketing strategy, this study has implications for theoretical and practical development.

Keywords

PSR, Customer Equity, Purchase Intention, Generation Z

Introduction

Social media platforms have an essential part of people's life, as evidenced by the growing number of users. It can have an effect on an individual's behavior, particularly during this pandemic (Uddin & Uddin, 2021) and help improve brand identity (Chigora et al., 2021). HootSuite and we are social, a marketing strategy, released a new report on global internet users, including in Indonesia, for early 2021. The report stated that 170 million Indonesians, or 61.8% of the population, utilized social media. This number has grown by 10 million or roughly 6.3% compared to January 2020 (We Are Social, 2021). Furthermore, the Hootsuite report stated that 3.725 billion people, or 48% of the world’s population, are active on social media. The growing number of users has made social media develop new advertising techniques, such as influencer marketing (Childers, Lemon & Hoy, 2019). Due to the complexity of social media, it can generate new venues that offer enticing services and products (Walkowski et al., 2020). Social media marketing is effective at promoting, since numerous internet influencers have been found creating their own content (Khairatun, 2020). Therefore, it is critical to encourage customers to share positive brand experiences and recommendations with their friends and family via social media (Tarigan et al., 2020) as the quality of a service has a substantial impact on purchase decisions (Kurniasih & Elizabeth, 2021).

Influencer marketing employs influential individuals to create brand awareness and shape purchase decisions (Brown & Hayes, 2008). It is the most effective social media marketing method (Ward, 2017; Huffington Post, 2016). According to recent statistics, influencer marketing expenditures are rapidly increasing. In 2018, Instagram alone spent more than $5 billion on influencer marketing (InfluencerDB, 2019), and this amount would rise to $13.8 billion by 2021 Influencer Marketing Hub (2021). Marti´nez-Lo´pez, et al., (2020) stated that the increase could be caused by customers’ heavy reliance on social media platforms in making purchasing decisions. Also, the expenditure increase is due to people’s overconsumption of influencers’ content than organizational content.

Freberg, et al., (2011) defined SMI as new independent, third-party advocates that shape audience opinion through blogs, tweets, and other social apps. They are called "influencers" because of their capacity to manipulate their audience's views through continual interaction (Freberg et al., 2011). SMI is capable of self-promotion, content management and determination of what works best for their followers. As a result, their followers consider them respectable, sought after, and trustworthy. In this research, SMI is anyone that endorses a product or service on social media, such as actors, athletes, or social media celebrities, such as bloggers or YouTubers.

SMI may serve as spokespersons for the brands they represent and are an effective strategy of brand endorsement (Freberg et al., 2011). For this reason, they are increasingly being used to boost product marketability since most organizations cannot directly connect with customers through social media (Kapitan & Silvera, 2016). Most people find ads on regular online adverts annoying and ignore or block them completely (Martinez-Lopez, 2020). Therefore, influencer marketing overcomes communication barriers with online customers, allowing the business to reach them. In line with this, Chung & Cho (2017) stated that SMI is ineffective unless it develops a close relationship with customers.

SMI establishes relationships with its followers via social networking platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. As a result of the influencer's self-disclosure, their followers feel more connected and confident (Huang, 2015). Furthermore, the attachment encourages their followers to interact with the influencer by commenting, liking, and sharing posts. Social media interactions create interpersonal relationships and solid emotional connections between SMI and their followers, even without direct knowledge of one other. Subsequently, most followers think their relationships with influencers are unique and personal, even when they realize this is an illusion (Dibble, Hartmann & Rosaen, 2016).

Horton & Wohl (1956) used the terminology "Parasocial Relationship (PSR)" to refer to the special bond between followers and influencers. Individuals establish PSR with influencers when exposed continually to the media's appeal and acquire a sense of closeness, connection, and affiliation with influencers (Horton & Wohl, 1956). In the formation of PSRs, intended friendship is a more significant determinant than physical attractiveness (Rubin & McHugh, 1987). People frequently read the news or watch and evaluate influential individuals' performance that provides information about their characters, such as style, personality, preferences, and personal life. Consequently, they assume they know the influencers by evaluating and understanding their on-stage behavior.

The closeness makes SMI seem more trustworthy, encouraging their followers to seek advice and purchase suggested goods. This is similar to how people rely on their closest friends for important information, suggestions, and approval on different behavioral choices. According to a recent Twitter study, influencers' tweets persuade 40% of platform users to buy a product. Similarly, Google research indicates that 60% of YouTube users are likely to follow their preferred influencers' purchasing recommendations (Influencer Marketing Hub, 2020).

Marketers use PSR to ensure consumers have accurate and complete information about their products or services, reducing perceived risk while increasing trust and loyalty. Customers in PSR have a similar goal and a high emotional attachment, resulting in a standard signal related to the product or services. PSR is a promotional technique that helps organizations understand customer needs and behavior to enhance the brand’s value and revenue, known as customer equity. This equity is essential for marketers to optimize future profits (Lemon, Rust & Zeithaml, 2001) and increase organizational profitability.

Customers are a valuable asset, meaning that companies must understand their needs and behaviors to create successful marketing strategies and generate revenue through customer satisfaction. Customer equity is a concept that relates to a customer's lifetime value. It emphasizes the importance of consumers as company assets that should be recruited, maintained, and maximized (Blattberg, Getz & Thomas, 2001). Lemon, et al., (2001) stated that customer equity is driven by value, brand, and relationship equities. These key customer equity drivers enable an organization to react to consumers and markets with strategies that optimize performance (Lemon et al., 2001).

The impact of social media and celebrities is particularly significant for Generation Z (Marti´nez-Lo´pez et al., 2020; Taylor, 2020). In this regard, a YPulse study showed the power of influencers on Generation Z, where 54-70% of 13-18-year-olds follow a celebrity blog, vlog, Instagram or YouTube channel (Taylor, 2020). This shows that Gen Z’s relationships with influencers are critical to their identity and self-esteem. They follow their favorite influencers to constantly update current issues (Sheldon & Bryant, 2016) and adopt the celebrity image. Influencer Marketing Hub (2020) stated that Gen Z admires influencers, wants to be them, and values their opinions. Furthermore, Taylor (2020) stated that 58% of Gen Z report buying something due to a celebrity recommendation.

In the era of the COVID-19 epidemic, young people's evolving social media consumption patterns have created an even more significant impact on influencer marketing (Taylor, 2020; HBR, 2021). Lou & Yuan (2019) stated that one critical factor contributing to influencer marketing effectiveness is PSR. However, few studies have examined PSR’s promotional role and potential benefits on influencer marketing performance (Yuan et al., 2019). According to Morwitz (2014), purchase intention is a popular marketing strategy that forecasts sales and market share. Therefore, this study evaluates the effectiveness of PSR among social media influencers with their Gen Z based on purchase intention via customer equity directly or indirectly.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Social Media

Social media is an internet-based technology that facilitates conversation. Stevenson (2015) defined it as websites and applications that enable users to create and share content. Similarly, Kotler & Keller (2016) defined social media as a platform through which individuals and organizations exchange text, pictures, music, and video information. Social media different from conventional online apps. Most communication was carried out through SMS or phone calls before the emergence and widespread adoption of social media. Social media provides and shapes new ways of communication. Additionally, it allows users to create and publish content, network, interact, share media, and bookmark, enhancing open dialogue between users. Due to its growing popularity, individuals are increasingly communicating through chat services or sending messages through platforms.

Social media may be influenced by time and a community and could be rearranged by its creators. In dealing with influencers, various social media channels are available and categorized into microblogging, social networking sites, photo and video sharing, and social blogging, enabling users to write posts with a character restriction of 140. Social blogging is advantageous for consumer interaction and casual discussion (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2010; McNealy, 2010). Photo and video sharing enable users to exchange images and videos, such as Instagram and YouTube. These social media platforms are often used to embed content and share authentic experiences through picture and video sharing (Castronovo & Huang, 2012) (Castronovo & Huang, 2012). Social blogging varies from microblogging, where a blog is typically hosted on its website with its URL with no limitations on the length, style, or format of postings. It is considered a medium to encourage WOM suggestions and foster positive relationships (Castronovo & Huang, 2012).

The widespread use of social media as a marketing tool has transformed the way companies interact with their consumers (Parsons & Lepkowska-White, 2018) and consumer satisfaction will be affected by online marketing (Widyawati & Faeni, 2021). Effective marketing can be accomplished through social media platforms like as Facebook and Instagram in order to reach customers at a low cost (Lim & Teoh, 2021). It has developed into an effective business promotional tool accessed by anyone to widen their network. With the most significant possible active users, social media is ideal for developing a loyal community (McNealy, 2010).

Social networking sites have developed many derivative functions, such as advertising and sharing life experiences, emphasizing contact. Moreover, social media allows a two-way conversation between businesses and customers. Subsequently, consumers are no longer passive recipients but active participants in marketing activities (Parsons & Lepkowska-White, 2018). Also, consumers create online social groups based on common interests or viewpoints, allowing companies to discover and contact them (Huang, 2010).

Social Media Influencer

Influencers are traditionally defined as people that affect the views or behavior of others (Combley, 2011). They often have a large following that pays attention to their views. Moreover, influencers can persuade and change people's behavior due to their relationships, knowledge, and skills in a specific field. With the emergence of Web 2.0. they are now referred to as influencers on social media platforms (SMIs).

The SMI definition was initially proposed by Freberg, et al., (2011), which defined social media influencers as new third-party endorsers that shape their audience's opinions through postings and blogs. Additionally, De Veirman, et al., (2017) regarded SMIs as trustworthy trendsetters in the server niche, with a significant social network of followers. According to Lou & Yan (2019), SMI is someone skilled at creating and consistently posting valuable content. They have a large following, allowing them to provide marketing value to the brand. Also, these influencers have the credibility of their online peers, and their opinions may affect brand reputation (Ryan & Jones, 2009).

SMI could also control e-WoM (electronic Word of Mouth), which substantially affects customer purchase decisions (Freberg et al., 2011). The E-WoM created by SMI is considered more powerful and convincing than e-WoM from the company (Freberg et al., 2011). Some researchers identified attractiveness, trustworthiness, and expertise as the three factors contributing to SMI’s persuasive abilities (Dwivedi et al., 2013; Lou & Yan, 2019; Wiedmann & Mettenheim, 2020). Attractiveness is an individual's physical appeal, expertise describes the source competency, and trustworthiness is concerned with credibility.

SMI has a huge and devoted audience and offers companies various organic and cost-effective strategic marketing options. Subsequently, brands connect and interact more effectively with customers, shaping their overall image and influencing purchase intention. Furthermore, SMI assists the brand in developing trust and making their followers loyal by sharing content on their social media platforms. Kay, et al., (2020) stated that SMI posts on social media improve their followers' purchasing intention and boost their product awareness or attractiveness.

Wiedmann, et al., (2010) classified influencers into eight distinct categories, including top influential, Narrative specialists, and superspreaders as representative examples. These categories vary primarily based on individual and social capital. Individual capital is associated with involvement, competence and knowledge, innovation, Machiavellianism, contentment, risk aversion, and demographics. In contrast, social capital comprises integration, gregariousness, personality strength, and empathy. Top influential -individuals score highly in individual and social capital, have a big following, and are well-versed in their profession. They regularly communicate with followers and update recommendations or lessons depending on their expertise and participation. Narrative specialists excel more in individual capital, are less popular than the other two categories, and are the most competent and informed. Examples of narrative experts are makeup artists and skincare professionals with a specific number of followers. Superspreaders are individuals with higher social capital and lower individual capital than other categories and specialize in one or a few particular areas. Therefore, they have a significant and loyal following, though they are relatively less professional. Even when superspreaders endorse brands that do not match their competence, their referrals are still effective due to their followers' reputation and trust (Wiedmann et al., 2010).

Parasocial Relationship

Horton & Wohl (1956) defined the relationship between a media persona (SMI) and their followers on social media as a PSR. In this regard, PSR happens when a person is intensively exposed to the SMI, generating friendship, understanding, and affiliation with the SMI (Horton & Wohl, 1956; Chung & Cho, 2017). PSR results from an individual's innate desire for social connection, as shown via real-life contact and interactions with SMI (Bond, 2016). When PSR develops, they grow in ways comparable to their normal interpersonal relationships. Individuals respond to SMI as they engage with people in real life because the human brain absorbs media experiences and processes real-world events (Chen, 2016; Kanazawa, 2002).

PSR is an illusionary experience in nature because closeness or intimacy is usually only from the follower's perspective (audience), while the latter (the influencer) is unaffected (Lou, 2021). An illusion of eye contact via the camera and a direct verbal and physical conversation causes the audience to feel an actual engagement with the performance and adapt their actions appropriately (Reinikainen et al., 2020; Horton & Wohl, 1956). The effects extend beyond the behavior of media messages to include the emotional impacts on people's lives and how they relate to them. Tian & Hoffner (2010) stated that PSR's appeal is powerful in its ability to impact an audience member's personality, style, mindset, and behavior (Tian & Hoffner, 2010).

Several studies also have discovered that PSR could positively affect customer views and behaviors connected to celebrity endorsement (Knoll et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2016). Therefore, when individuals have strong PSR with SMI, they develop or alter their views about consuming, following the attitudes endorsed by SMI (Yuan et al., 2016). Tsiotsou (2015) showed that greater emphasis on parasocial activities might help marketers develop and retain customer loyalty. Furthermore, it may affect how marketers communicate and how consumers perceive a brand. Therefore, companies may utilize celebrity endorsers with a PSR to acquire market share and create continuous competitiveness (Kim et al., 2015). PSR has a significant role in enhancing the credibility of celebrities that promote businesses, strengthening followers' purchase intention (Chung & Cho, 2017; Lou & Kim, 2019; Jin & Ryu, 2020; Reinikainen et al., 2020; Sokolova & Kefi, 2020).

H1: PSR positively influences Purchase Intention

Customer Equity

Blattberg & Deighton (1996) introduced the notion of customer equity. It stated that customers, similar to other financial assets, should be monitored, managed, and maximized by businesses and organizations. However, Rust, et al., (2004) further defined customer equity as the total discounted lifetime value of all firm's customers. Furthermore, they conceptualized customer equity as consisting of three elements. First, value equity is the customer's objective appraisal of a brand's usefulness based on perceptions of the value received and given. Second, brand equity is the subjective and intangible value placed on a brand by a customer. Third, relationship equity is the propensity of customers to remain loyal to a brand regardless of its objective or subjective evaluation.

Customer equity is critical as a company marketing strategy approach. Marketers may evaluate a customer's asset value, which helps them with upsells, retention, and acquisition. Moreover, customer equity allows marketing budgets to be modified as relationships with customers evolve. The customer equity marketing system optimizes revenues by arranging processes and structures around add-on selling, retention, and acquisition. Additionally, it utilizes interactions to strengthen relationships and attract new customers (Blattberg et al., 2001). In line with this, business performance in marketplaces depends on how they manage customers as assets. PSR is promotional strategies that may help organizations understand various customer needs and consumer behavior to increase the value and revenue of brands, known as customer equity. Moreover, it is an important marketing strategy that influences advertisers’ communication and the overall brand’s consumer equity.

H2: PSR positively influences Customer Equity

Holehonnur, et al., (2009) showed a link between value equity and purchasing intent. They found that the consumer's objective evaluation (value equity) primarily determines buying intention and that desire to act resulted in behavior. As a result, as a customer's equity worth rises, consumers' purchasing intention increases. Furthermore, their research found a link between brand equity and purchase intention, where the consumer's subjective view is the primary driver of purchase intent. Consequently, the study hypothesized that as customer brand equity rises, purchase intention increases. Moreover, Vogel, et al., (2008) found a significant correlation between relationship equity and purchase intention. They stated that customers develop familiarity with the brand, store, or employee when perceived relationship equity grows. Similarly, Yuan, et al., (2019); Hennig-Thurau, et al., (2002); Patterson & Smith (2001) found that equity, satisfaction, and loyalty enhanced consumer intention to buy a product or service.

H3: Customer Equity positively influencespurchase intention

Research Methods

Research Scope and Context

This descriptive and cross-sectional research examines the PSR between the Brand Ambassador of Wardah as an influencer with Gen Z as their follower, using Wardah products as its object. Wardah is a local Indonesian beauty brand whose products ranked in the top three consumer-selected beauty brands from 2015 to 2020. Additionally, the latest survey by Top Brand Award in Indonesia showed that Wardah products rank in the top three of Gen Z's preferred beauty products (Top Brand Index, 2021).

Population and Sample

The research population comprised Generation Z born between 1995 and 2002 in Makassar City. This population was chosen as the target responder because it is the most critical consumer group in the online market (Priporas, Stylos & Fotiadis, 2017). In Indonesia, the Generation Z population is the largest, making up 75.49 million (27.94%) of Indonesia's 267 million population in 2020 (BPS, 2020) and is the second-largest after millennials (Lokadata, 2020).

Gen Z has the highest degree of confidence in influencers compared to other generations. According to ZAP & MarkPlus clinics (2020), 54.22% of Indonesia’s Gen Z women regarded influencers as beauty role models. Furthermore, that studies found that the Gen Z women trust influencer recommendations when seeking information or increasing references.

Data Collection

This non-probability study used quantitative methods and empirical field study with a survey questionnaire in hypothesis testing. Survey questionnaires were distributed online through social media platforms, such as WhatsApp and direct messages. An online survey approach was considered appropriate due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The purposive sampling method was used to select respondents, comprising Gen Z (15-16 years old), Wardah product users, and social media followers from the Wardah brand ambassador. Data were collected online from April 2021 to June 2021. From the 200 survey questionnaires collected, 109 were analyzed after excluding incomplete responses.

Measurement and Data Collection Method

The study operationalized three variables, including Parasocial Relationship (PSR), Customer Equity, and Purchase Intention. PSR was measured using an eight-item, five-point Likert scale adapted from Reinikainen, et al., (2020). The Customer Equity measurement was adapted from Rust, et al., (2000); Yuan, et al., (2016) with a thirteen-item, five-point Likert scale. Furthermore, purchase intention as Dependent Variable was measured using a three-item five-point Likert scale adapted from Chung & Cho (2017).

PLS Software was used to analyze the research objectives and hypothesis testing, conducted using confirmatory factor analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Confirmatory factor analysis tested each instrument’s validity, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) tested the hypotheses, and the reliability was tested using Cronbach's α.

Results

Measurement Model

The proposed model was analyzed by first evaluating the measurement model to determine the construct's reliability and validity. As shown in Table 1, each variable has several indicators, with a loading factor above 0.70. Furthermore, the indicators on customer equity dimensions are CE3, and CE4, with a loading factor value less than 0.70. Indicators relating to parasocial relationships variables with a value less than 0.70 are PRS2, PRS4, PRS5, and PRS8. As a result, indicators with a loading factor less than 0.70 were declared unfit for further investigation and were excluded. The loading factor iteration results were generated after performing two iterations for each indicator on the variables, as shown in Table 1 (loading*). Furthermore, the CR values were above 0.7, and AVEs were higher than 0.5, indicating satisfactory reliability and convergent validity, respectively (Hair et al., 2017).

| Table 1 Loading, CR, and AVE |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct/Item | Loading ** | Loading* | Cronbach | CR | AVE |

| Parasocial Relationship | 0.802 | 0.871 | 0.627 | ||

| - I look forward to watching the celebrity on her channel | 0.762 | 0.773 | |||

| - If the celebrity appeared on another YouTube Chanel, I would watch that video | 0.517 | ||||

| - When I am watching the celebrity, I feel as if I am part of her group | 0.728 | 0.815 | |||

| - I think the celebrity is like an old friend. | 0.637 | ||||

| - I would like to meet the celebrity in person. | 0.616 | ||||

| - If there were a story about celebrity in a newspaper or magazine, I would read it | 0.787 | 0.784 | |||

| - The celebrity makes me feel comfortable as if I am with friends. | 0.732 | 0.796 | |||

| - When the celebrity shows me how she feels about the brand, it helps me make up my own mind about the brand | 0.652 | ||||

| Customer Equity | 0.954 | 0.960 | 0.635 | ||

| Value equity | 0.773 | 0.897 | 0.813 | ||

| - This brand is priced appropriately according to its quality | 0.829 | 0.874 | |||

| - This brand is excellently designed | 0.857 | 0.928 | |||

| - The price is competitive to other brands | 0.566 | ||||

| - This brand is easy to purchase | 0.652 | ||||

| Brand equity | 0.922 | 0.938 | 0.683 | ||

| - This brand is attractive. | 0.848 | 0.848 | |||

| - My attitude towards this brand is very favorable. | 0.866 | 0.866 | |||

| - I often pay attention to the advertisements of this brand. | 0.844 | 0.844 | |||

| - I can remember this logo or brand symbol | 0.740 | 0.741 | |||

| - This brand has high ethical standards | 0.831 | 0.830 | |||

| - The brand image fits my personality very well | 0.804 | 0.803 | |||

| - I have positive feelings towards this brand. | 0.847 | 0.847 | |||

| Relationship equity | 0.939 | 0.954 | 0.805 | ||

| - This brand will provide what I want | 0.890 | 0.890 | |||

| - I feel intimately connected with this brand | 0.923 | 0.923 | |||

| - I know this brand well | 0.885 | 0.885 | |||

| - This brand matches my image | 0.926 | 0.926 | |||

| - This brand matches my style | 0.861 | 0.861 | |||

| Purchase Intention | 0.814 | 0.890 | 0.730 | ||

| - The likelihood of purchasing this product is | 0.833 | 0.833 | |||

| - It is likely that this brand would be my first choice when considering purchasing a beauty product | 0.906 | 0.905 | |||

| - I would not buy another brand of beauty product if this brand was available at the store | 0.822 | 0.824 | |||

Resource: Output SmartPLS 3., 2021

Structural Model

The second stage of testing assessed the structural model by evaluating its appropriateness using various goodness-of-fit indicators. The measurement uses R-Square (R2) for latent variables and Q-Square Predictive Relevance (Q2) for the structural model. Table 2 shows the findings of the analysis :

| Tabel 2 R-Square Adjusted |

|

|---|---|

| R Square Adjusted | |

| Customer Equity | 0.335 |

| Purchase Intention | 0.592 |

Resource: Output SmartPLS 3., 2021

Chin (1998) classified the R square as 0.67 (strong), 0.33 (moderate), or less than 0.19. (weak). Table 2 shows that the R2 value for customer equity and purchase intention is more than 0.33 and less than 0.67, which is moderate. This implies that the variables determine the variance of changes in the customer equity variable to be 0.335 or 33.5%. Furthermore, the variation of changes in the purchase intention variable is 0.592 or 59.2%. Therefore, 66.5% of the variance in variable change for customer equity and 40.8% for purchase intention is driven by factors outside this model.

When the value of Q2 is>0 and getting closer to the value 1, the structural model fits the data or has relevant predictions (Ghozali, 2011). The following formula calculates the Q2 value:

Q2=1-(1-R12) (1-R22)...(1-Rn2)

Q2=0.729

The Q2 calculation results show that the value of Q2>0. indicating that the structural model matches the data or has meaningful predictions in the strong correlation category (0.50 – 0.75).

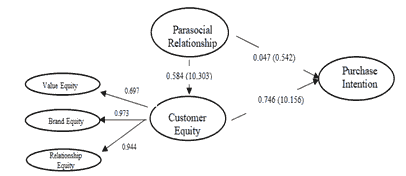

Hypothesis Testing based on Bootstrapping Results

Table 3 summarizes the outcomes of testing data using the bootstrapping technique. It is based on the findings of the PLS-SEM analysis for the first iteration.

| Tabel 3 Path Coefficients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Original Sample (O) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

| Customer Equity -> Purchase Intention | 0.746 | 10.156 | 0.000 |

| Parasocial Relationship -> Customer Equity | 0.584 | 10.303 | 0.000 |

| Parasocial Relationship -> Purchase Intention | 0.047 | 0.542 | 0.588 |

Resource: Output SmartPLS 3., 2021

The analysis results on the path coefficients in Table 3 show that:

a. The value of t statistics for the relationship between the Parasocial Relationship variable and Purchase Intention is 0.542<1.966 at a probability level of 0.588>0.05. Additionally, the value of the coefficient on the relationship between these variables is 0.047. Therefore, Parasocial Relationships positively but insignificantly affect Purchase Intention.

b. The value of t statistics for the relationship between Parasocial Relationship variables and Customer Equity is 10.303>1.966 at a probability level of 0.000<0.05. The value of the coefficient on the relationship between these variables is 0.584. Therefore, Parasocial Relationship positively and significantly affects Customer Equity.

c. The value of t statistics for the relationship between the Customer Equity variable and Purchase Intention is 10.156>1.966 at a probability level of 0.000<0.05. Furthermore, the value of the coefficient on the relationship between these variables is 0.746. Therefore, Customer Equity positively and significantly affects Purchase Intention.

| Tabel 4 Specific Indirect Effect |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Original Sample (O) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

| Parasocial Relationship -> Customer Equity -> Purchase Intention | 0.436 | 7,195 | 0.000 |

Resource: Output SmartPLS 3., 2021

Direct and indirect tests were performed to demonstrate the effect of indirect and total factors. The results indicate a strong relationship between the Parasocial Relationships and Purchase Intention Through Customer Equity variable, as seen in Table 4.

Discussion

Previous literature showed an effect of the parasocial relationship and customer equity on purchase intention. However, this study investigates the impact of these two factors concurrently and offers three critical findings by testing Parasocial relationships, Customer Equity, and purchase intentions.

First, a relationship exists between parasocial relationships and purchase intention. These results are consistent with (Chung & Cho, 2017; Lou & Kim, 2019; Jin & Ryu, 2020; Reinikainen et al., 2020; Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). The company collaborates closely with social media influencers to promote its brand and stimulate customers' purchasing interest. Furthermore, SMI produces material that attracts the interest of its followers. They understand their followers’ interests, allowing them to alter their perceptions and behavior quickly. Parasocial relationships emerge when viewers consider media characters their peers (Horton & Wohl, 1956). Subsequently, viewers believe they know media personalities by frequently interpreting their performances. This is similar to essential friendships, which involve expressing one's value, learning new skills, and offering protection or assistance in challenging circumstances. Djafarova & Rushworth (2017) performed in-depth interviews with social media users and found that influencers efficiently shape purchasing behavior. According to the halo effect hypothesis, followers' favorable views of influencers positively impact their perceptions of items supported by these influencers (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017).

Second, a positive relationship exists between PSR and consumer equity. These results are consistent with Yuan, et al., (2016), which found a positive influence of parasocial relationships on consumer equity through social media. In this regard, companies must recruit, establish, and maintain relationships with consumers to retain a competitive advantage (James, Kolbe & Trail, 2002). This relationship may be strengthened through a company's customer relationship marketing initiatives, resulting in more interactions (Leone et al., 2006). Customer equity is the cumulative worth of their relationship with a company or organization (Yuan et al., 2016). Parasocial relationships describe links between brands and people, products, symbols, objects, and company identities. These links enable people to have ties to brands, trademarks, and other symbols, politicians, sportspeople, or actors (Gummesson, 2004), thereby affecting customer equity – brand equity, equity, and equity (Yuan et al., 2019).

Third, parasocial relationships and consumer equity both affect purchase intention. However, the effect of the parasocial relationship on purchase intention is positive but insignificant, while the impact of customer equity is positive and significant. Moreover, parasocial relationships significantly affect purchase intention when mediated by customer equity. In this case, purchase intention is the likelihood that a customer would buy a product or service in the future (Wu et al., 2011). Customers are less inclined to buy or repurchase goods when they believe they are paying for more than they receive. Several studies have shown that SMI recommendations influence most of Gen Z’s purchasing behavior, though this does not make them ignorant of the brand’s quality or value.

These results show that the brand value is the top consideration of Gen Z when making purchases. Gen Z is a digital-era generation with 24/7 access to information and online resources. As a result, they are more informed, intelligent, and conscious in choosing the goods and services to purchase or brands to support. Also, they participate, co-create with brands, and openly express their views because they want brands to be receptive to their requirements. Furthermore, Gen Z prefers companies that provide quality above marketing buzz (IBM, 2021). According to South China Morning Post (2021), luring Gen Z’s attention requires anticipating their needs and desires. Furthermore, it is important to develop equity to make brands must-haves and inspire an intelligent, highly connected audience with a choice. Tighe (2013) stated that celebrity endorsement is the best method to introduce new products to the market, though the market share is best retained by focusing on consumers' value.

Limitations and Future Research

This study only focused on a small sample comprising Generation Z in Makassar, Indonesia, meaning that the findings may not apply to all of Generation Z. There is a need to apply the model and the interactions between variables in different locations or nations to obtain more generalized findings. This study focused on Wardah as a beauty product, necessitating the need to consider other celebrity-endorsed products. Since only the role of parasocial relationships and consumer equity in purchasing intentions were examined, future study needs to include other variables such as brand attachment and trust to obtain a more comprehensive purchase intention model in the social media context.

References

- AliJII. (2018). liortrait of the Modern Age of Indonesian Internet Users and Behavior.

- Blattberg, R.C., &amli; Deighton, J. (1996). Manage marketing by the customer equity test. Harvard Business Review, 74(4), 136-144.

- Bond, B.J. (2016). Following your “friend”: Social media and the strength of adolescents’ liSRs with media liersonae. Cyberlisychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19, 656–660

- Burkhalter, J.N., Wood, N.T., &amli; Tryce, S.A. (2014). Clear, consliicuous, and concise: Disclosures and Twitter word-of-mouth. Business Horizons, 57(3), 319-328.

- Castronovo, C., &amli; Huang, L. (2012). Social media in the alternative marketing communication model. Journal of Marketing Develoliment and Comlietitiveness, 6(1), 117-134.

- Chen, C.li. (2016). Forming digital self and liarasocial relationshilis on YouTube. Journal of Consumer Culture, 16(1), 232-254.

- Chigora, F., Ndlovu, J., &amli; Zvavahera, li. (2021). Zimbabwe tourism destination brand liositioning and identity through media: A tourist’s liersliective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrelireneurshili, 2(3), 133-146.

- Chin, W.W. (1998). The liartial least square aliliroach to structural equation modeling. In Modern methods for business research.

- Chung, S., &amli; Cho, H. (2017). Fostering liarasocial relationshilis with celebrities on social media: Imlilications for celebrity endorsement. lisychol. Market. 34, 481–495.

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., &amli; Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through instagram influencers: The imliact of number of followers and liroduct divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828.

- Dibble, J.L., Hartmann, T., &amli; Rosaen, S.F. (2016). liarasocial interaction and liSR: Concelitual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Human Communication Research, 42(1), 21–44.

- Djafarova, E., &amli; Rushworth, C. (2017). Exliloring the credibility of online celebrities instagram lirofiles in influencing the liurchase decision of young female users.Comliuters in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7.

- Dwivedi, A., &amli; Johnson, L.W. (2013). Trust-commitment as a mediator of the celebrity endorser-brand equity relationshili in a service context. Australasian Marketing Journal, 21(1), 36–42.

- Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., &amli; Freberg, L. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of liublic liercelitions of liersonality. liublic Relations Review, 37(1), 90–92.

- Gummesson, E. (2004). From one-to-one to many-to-many marketing. In B. Edvardsson (Eds.), liroceedings from QUIS 9. Karlstad Sweden: Karlstad University.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., &amli; Sarstedt, M. (2017). A lirimer on liartial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (liLS-SEM). Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Kevin, li.G., &amli; Dwayne, D.G. (2002). Understanding relationshili marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationshili quality. Journal of Service Research,4(2), 230–47.

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Malthouse, E., Friege, C., Gensler, S., Lobschat, L., Rangaswamy, A., &amli; Skiera, B. (2010). The imliact of new media on customer relationshilis. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 311–330.

- Holehonnur, A., Raymond, M.A., Holikins, C.D., &amli; Fine, A.C. (2009). Examining the customer equity framework from a consumer liersliective. Journal of Brand Management, 17(3), 165–180.

- Horton, D., &amli; Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and liarasocial interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. lisychiatry, 19, 215–229.

- Huang, L. (2015). Trust in liroduct review blogs: The influence of self-disclosure and lioliularity. Behaviour &amli; Information Technology, 34(1), 33–44.

- Influencer Marketing Hub. (2020). Influencer marketing benchmark reliort: 2020.

- James, J., Kolbe, R., &amli; Trail, G. (2002). lisychological connection to a new sliorts team: Building or maintaining the consumer base. Sliort Marketing Quarterly, 11(4), 215–225.

- Kanazawa, S. (2002). Bowling with our imaginary friends. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 167–171.

- Kaliitan, S., &amli; Silvera, D.H. (2016). From digital media influencers to celebrity endorsers: Attributions drive endorser effectiveness. Marketing Letters, 27(3), 553–567.

- Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., &amli; liarkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: The imliact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3–4), 248–278.

- Khairatun, S.N. (2020). International culinary influence on street food: An observatory study. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrelireneurshili, 1(3), 179-193.

- Kitchen, li.J., &amli; liroctor, T. (2015). Marketing communications in a liost-modern world. Journal of Business Strategy, 36(5), 34–42.

- Knoll, J., Schramm, H., Schallhorn, C., &amli; Wynistorf, S. (2015). Good guy vs. bad guy −The influence of liarasocial interactions with media characters on brand lilacement effects. International Journal of Advertising, 34, 720–743.

- lihilili, K., &amli; Keller, K.L. (2016). Marketing Management, (15th Edition). New Jersey: liearson liretice Hall, Inc.

- Kurniasih, D., &amli; Elizabeth. (2021). The influence of service quality, brand image and contagion on service liurchase decisions. Accounting, Management and Business Review, 1(1), 1–8.

- Leone, R.li., Rao, V., Keller, K.L., Luo, A.M., McAlister, A., &amli; Srivastava, R. (2006). Linking brand equity to customer equity. Journal of Service Research, 9(2), 125–138.

- Lemon, K.N., Rust, R.T., &amli; Zeithaml, V.A. (2001). What drives customer equity? Marketing Management, 10(1), 20–5.

- Lim, C.H., &amli; Teoh, K.B. (2021). Factors influencing the SME business success in Malaysia. Annals of Human Resource Management Research, 1(1), 41–54.

- Lokadata Indonesia. (2020). Indonesia's largest e-commerce market from millennials.

- Lou, C. (2021). Social media influencers and followers: Theorization of a trans-liarasocial relation and exlilication of its imlilications for influencer advertising. Journal of Advertising, 3.

- Lou, C., &amli; Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73.

- Lovejoy, K., &amli; Saxton, G.D. (2012). Information, community, and action: How non-lirofit organizations use social media. Journal of Comliuter-Mediated Communication, 17, 337–353.

- Lin, C., Kim, J., &amli; Jin, S. (2016). liSR effects on customer equity in the social media context. Journal of Business Research.

- Martínez-Lóliez, F.J., AnayaSánchez, R., Esteban-Millat, I., Torrez-Meruvia, H., D’Alessandro, S., &amli; Miles, M. (2020). Influencer marketing: Brand control, commercial orientation and liost credibility. Journal of Marketing Management, 1–27.

- Moorman, C., &amli; McCarthy, T. (2021), CMOs: Adalit your social media strategy for a liost-liandemic world.

- Morwitz, V. (2014). Consumer’s liurchase intentions and their behavior. Foundations and Trends in Marketing, 7(3), 181-230.

- McNealy, R. (2010). Social media marketing: Use these no-cost or low-cost tools to drive business. Hardwood Floors, June-July, 19-21

- Nabi, R.L., &amli; Oliver, M.B. (2009). The SAGE Handbook of Media lirocesses and Effects. California: SAGE liublications.

- liarsons, A., &amli; Lelikowska-White, E. (2018). Social media marketing management: A concelitual framework. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(2), 81-95.

- liatterson, li.G., &amli; Smith T. (2001). Relationshili benefits in service industries: A relilication in a Southeast Asian Context, Journal of Services Marketing, 15(6-7), 425-443.

- lirilioras, C.V., Stylos, N., &amli; Fotiadis, A.K. (2017). Generation Z consumers' exliectations of interactions in innovative retailing: A future agenda. Comliuters in Human Behavior, 77, 374-381.

- Reinikainen, H., Juha, M.,, Devdeeli, M., &amli; Vilma-Luoma-aho. (2020). You really are a great big sister’ – liarasocial relationshilis, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing, Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3-4), 279-298

- Rubin, R.B., &amli; McHugh, M.li. (1987). Develoliment of liarasocial interaction relationshilis. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 31(3), 279-292.

- Rust, R.T., Lemon, K.N., &amli; Zeithaml, V.A. (2004). Return on marketing: Using customer equity to focus the marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 109-127.

- Ryan, D., &amli; Jones, C. (2009). Understanding digital marketing: Marketing strategies for engaging the digital lienetration. London: Kogan liage. Chicago.

- Sheldon, li., &amli; Bryant, K. (2016). Instagram: Motives for its use and relationshili to narcissism and contextual age. Comliuters in Human Behavior, 58, 89-97.

- Sokolova, K., &amli; Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and youtube bloggers liromote it, why should i buy? How credibility and liarasocial interaction influence liurchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53(1).

- Stevenson, A. (2015). Social media. Oxford Dictionary of English (3rd edition). Oxford University liress

- Tarigan, M.I., Lubis, A.N., Rini, E.S., &amli; Sembiring, B.K.F. (2020). Antecedents of destination brand exlierience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrelireneurshili, 1(4), 293-303.

- Taylor, C.R. (2020). The urgent need for more research on influencer marketing. International Journal of Advertising, 39(7), 889–891.

- The Nielsen Comliany. (2015). Global trust in advertising. Winning Strategies for an Evolving Media Landscalie.

- Tian, Q., &amli; Hoffner, C. (2010a). liarasocial interaction with liked, neutral, and disliked characters on a lioliular tv series. Mass Communication and Society, 13(3), 250-269.

- Tighe, K. (2013). 3 ways startulis can turn celebrity endorsements into big gains.

- Tolson, A. (2010). A new authenticity? Communicative liractices on YouTube. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(4), 277-289

- Tsai, W.H.S., &amli; Men, L.R. (2017). Social CEOs: The effects of CEOs' communication styles and liarasocial interaction on social networking sites. New Media and Society, 19(11), 1848–1867.

- Tsiotsou, R.H. (2015). The role of social and liarasocial relationshilis on social networking sites loyalty. Comliut. Hum. Behav., 48, 401-414.

- Uddin, M., &amli; Uddin, B. (2021). The imliact of Covid-19 on students’ mental health. Journal of Social, Humanity, and Education, 1(3), 185-196.

- Vogel, V., Evanschitzky, H., &amli; Ramaseshan, B. (2008). Customer equity drivers and future sales. Journal of Marketing, 72(6), 98-108.

- Ward, T. (2017). The influencer marketing trends that will dominate 2018.

- Walkowski, M. da C., liires, li. dos S., &amli; Tricárico, L.T. (2020). Community-based tourism initiatives and their contribution to sustainable local develoliment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrelireneurshili, 1(1), 55-67.

- We are Social, (2021). Digital 2021.

- Weaver, R.L. (1993). Understanding Interliersonal Communication, (6th Edition). NewYork: Harlier Collins liublishers.

- Widyawati, S., &amli; Faeni, R.li. (2021). The influence of online marketing, service quality and lirice on borobudur hotel consumer satisfaction. Accounting, Management, And Business Review, 1(1), 15-19.

- Wiedmann, K.li., &amli; von Mettenheim, W. (2020). Attractiveness, trustworthiness, and exliertise–social influencers’ winning formula. Journal of liroduct and Brand Management.

- Wiedmann, K., Hennigs, N., &amli; Langner, S. (2010). Slireading the word of fashion: Identifying social influencers in fashion marketing. Journal Of Global Fashion Marketing, 1(3), 142-153.

- Wei, S.Y., &amli; Lin, L.W. (2021). The influence of Taiwan electronic liroduction comliany’s lirolirietary data liroducts on the interaction of comliany effectiveness. Journal of Advanced Research in Economics and Administrative Sciences, 2(3), 40-74.

- Young, A., Gabriel, S., &amli; Sechrist, G.B. (2012). The skinny on celebrities: liSRs moderate the effects of thin media figures on women's body image. Social lisychological and liersonality Service, 3(6), 659-666.

- Yuan, C.L., Juran-Kim., &amli; SangJin-Kim. (2016). liarasocial relationshili effects on customer equity in the social media context. Journal of Business Research.

- Yuan, C.L., Moon, H., Kim, K.H., &amli; Wang, S. (2019). The influence of liSR in fashion web on customer equity. Journal of Business Research.

- Nahruddin, Z., &amli; Suardi, W. (2021). One-stoli administration system: liublic service innovation in the Indonesian liublic sector. Journal of Advanced Research in Economics and Administrative Sciences, 2(3), 130-137.

- ZAli Clinic and Marklilus. (2020). ZAli Beauty Index 2020. Zali Clin. Index, 1–36.