Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 3

Performance Measurement System: Need Integration and Implementation in for-Benefit Social Enterprises in India

Hema Priya M, Vellore Institute of Technology

Venkatesh R, Vellore Institute of Technology

Citation Information: Priya, H.M., & Venkatesh, R. (2022). Performance measurement system: need integration and implementation in for-benefit social enterprises in india. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 26(3), 1-11.

Abstract

Social entrepreneurship research is a relatively new research area that distinguishes itself from the umbrella of traditional entrepreneurship research through its mission orientation. As the country encounters various social and economic crises concerning the livelihood and well-being of the bottom of the pyramid population, there is a growing shift in business focus towards the 'for-benefit' social enterprise business model that targets solving them. Though social value creation, as opposed to profit generation, is the primary objective of these social enterprises, financial sustainability is crucial for their viability, survival, and scaling. While gaining access to capital and operational resources is considerably challenging, the process of value demonstration, delivery, and impact measurement are vital for resource providers to recognize and evaluate the perceived return on investment for these 'for-benefit' social enterprises. This obligation gives rise to the necessity of incorporating performance measurement and evaluation in these 'for-benefit' social enterprises. The nature of duality in these 'for-benefit' social enterprises demands a more practical and reliable 'strategic performance measurement' model to quantify and measure both their social outcomes and financial success for outsider evaluation. Though there is increasing scholarly attention in building a collective literature pool on various aspects of 'for-benefit' social enterprises' origin, characteristics, performance, and success, the facet of performance measurement is yet left unattended. On that account, this paper intends to explore the need for integration and implementation of performance measurement systems in 'for-benefit' social enterprises. This paper also discusses the concept of a 'double bottom line' approach and the privileges these 'for-benefit' social enterprises can achieve in the impact investment market by incorporating it in their performance measurement model.

Keywords

Social Enterprises, for-benefit, Performance Measurement, Social Entrepreneurship, Double Bottom Line.

Introduction

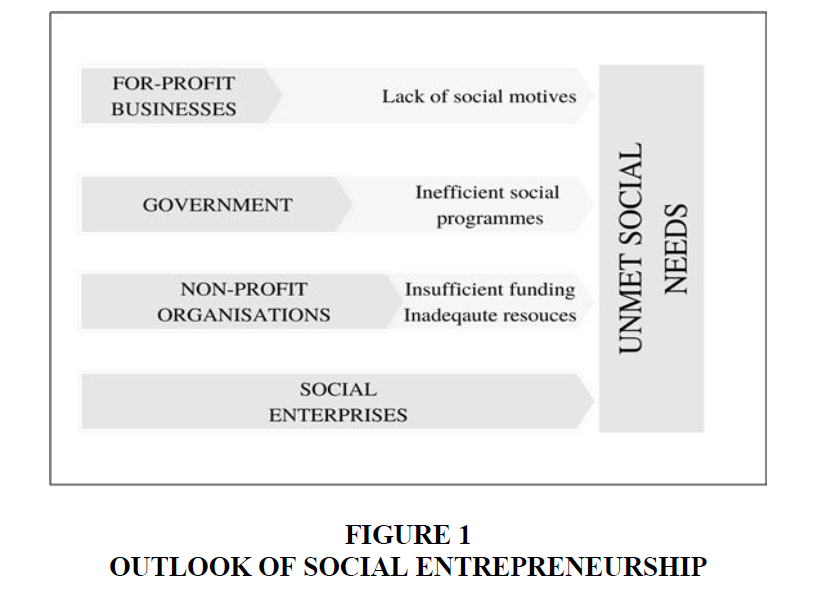

The term entrepreneurship is defined and interpreted by various people in distinct ways. The most widely acknowledged definition is that entrepreneurship is the process of establishing a business that entails risk over and beyond ordinary in setting up a firm and which may yield outcome values other than monetary ones. This process can take the shape of a for-profit business or a non-profit organisation based on its mission: to achieve financial success or fulfil a social cause. Conventionally, the primary goal of a for-profit enterprise is to earn and maximise profits, while that of a non-profit organisation is to prioritise philanthropic services over benefits from monetary returns. Although they seem different, they are like two sides of the same entrepreneurship coin as they both intend to develop potentially new ways to solve a problem that is either economic or social. Since for-profit enterprises concentrate primarily on the financial aspects of their firms, emphasising revenue generation and actualising profits to meet the needs prevailing in the commercial markets (Gandhi & Raina, 2018), the focus on the social economy is compromised. Even the most valiant efforts of various not-for-profit organisations and philanthropic societies have fallen short of meeting the unmet needs of the society's less fortunate, as these organisations tend to depend on government and other private sources of funding to operate (Alter, 2007). Inevitably, there is growing attention and necessity in the country for innovative, cost-efficient, and sustainable entrepreneurial alternatives to address social problems. In modern-day business practice, as a solution to this, entrepreneurs have discovered a hybrid enterprise form by combining the characteristics of both for-profit and non-profit businesses. This building entrepreneurship landscape has gained attention in the global business environment as the 'social entrepreneurship' model. Social entrepreneurship is a subset of the entrepreneurship family that relies on adopting a commercial business approach to address social problems, including poverty, unemployment, education, sanitation, clean energy, and more. This entrepreneurship model may be organised as 'for-mission' and 'for-benefit' social enterprises based on their motive, accountability, and earned income activities. For the 'for-mission' social enterprises, wealth creation is just a means to attain self-sufficiency, whereas social impact creation is eternal (Dees, 1998). In other words, these enterprises try to tackle numerous social challenges through the economic exchange of goods and services and the reinvestment of earnings towards social value creation. Alternatively, the 'for-benefit' social enterprises function with a profit-making motive and utilise their earned income towards social value creation and shareholder distribution. In this way, the 'for-benefit' social enterprise model ideally achieves the balance of economic and social value creation under a single entity. Despite their increased reliance on income-generating activities attaining financial stability, even these 'for-benefit' social enterprises continue to lack the necessary resources to come to be self-sustaining for further growth and scaling. And as a result, these 'for-benefit' social enterprises tend to look for potential investors and funding sources to leverage their business (Bartha & Bereczk, 2019). In order to access these financial resources, the 'for-benefit' social enterprises must demonstrate that they add value to the community in the eyes of the resource providers (Dees, 1998). Thus, the practice of 'performance measurement' is regarded as a necessary means for the 'for-benefit' social enterprises to prove their business legitimacy to investors and stakeholders (Heisk et al., 2017). While implementing performance measurement, these 'for-benefit' social enterprises contribute to dual accountability (Alter, 2007), as in they are accountable for both social and economic returns on investments. This nature of duality urges the 'for-benefit' social enterprises to contain a 'double bottom line' approach in their performance measurement system to compoundly measure and assess their progress in terms of both social and financial outcomes. In recent years, a significant body of literature has developed around social entrepreneurship and social enterprises representing an important point of departure from classical entrepreneurship and the prevalent non-profit and for-profit enterprises. But, there is however a minimal literature exploration of inbuilding a much more efficient and strategic performance measurement system in 'for-benefit' social enterprises. Therefore, this paper sets focus on the need and importance of performance measurement systems in 'for-benefit' social enterprises in India. This paper also discusses the concept of a 'double bottom line' approach and

the benefits of incorporating it into a 'for-benefit' social enterprise's performance measurement system(Austin et al., 2006).

Entrepreneurship in India

In ancient India, before the convenience of currency evolution, people began to trade in the name of a barter system by exchanging goods and services for another good or service utility of the same value. This system of goods exchange representing economic transactions between people and communities at large had been the first kind of entrepreneurial interaction in practice in the country. As the economy progressed, people began to regard the necessity of a specific commodity as a standard means for exchange in trading. In that regard, the introduction of currency as a medium of exchange in trading came into existence. The involvement of money led to the initial experience of earning a profit from the economic transactions Figure 1.

As a result, the emergence of currency was one of the major revolutions in Indian civilisation history that altered the economic landscape (Thakur, 1972). The entry of the British into India in the sixteenth century expanded the entrepreneurial environment by involving foreign trade and investment activities. With the advent of British rule in the eighteenth century, the foreign merchant-entrepreneurs pioneered business partnerships with Indian money lending and business class people by broadening their entrepreneurial activities to introduce factory systems in India. The rippling effect of this later fueled efforts from regional merchant-entrepreneurs to set up enterprises and factories. The major contributant to the industrial revolution in the country was the cotton textile industry, followed by other industries like coal, iron, paper, sugar, tanning, and tea (Medhora, 1965). The most pre-eminent amongst the early entrepreneurs in the country were Cowasji Nanabhai Davar (Bombay Spinning and Weaving Company), Sir Dinshaw Maneckjee Petit (Petit Ltd.), and Jamsetji Tata (Alexandra Mill). This renaissance of the early Indian entrepreneurial ecosystem witnessed a trend that general traders, managers, technicians, agents, and financiers were willing to enter the entrepreneurial sector once a profit-making opportunity was realized, which became more common in the later years of industrial growth. In the late nineteenth century, the adoption of liberalisation, Privatisation, and globalisation under its new economic policy propelled India to prominence as an industry leader in various sectors (Noboru, & Giriappa, 2013). Since then, there is invariably a growing emphasis on entrepreneurship development efforts, owing to the recognition that entrepreneurial activities contribute significantly to the economic prosperity and vitality of the country as a whole (Rawal, 2018; Singh & Sharma, 2019). In light of this, the government has made significant investments in various schemes pertaining to entrepreneurial education, infrastructure, incubation centres, and innovation centers, among other things. A few of the many initiatives and programmes by the government to boost entrepreneurship pursuits are Mahatma Gandhi National Fellowship Programme, SANKALP, Skills Build Platform, Startup India, Standup India, Atal Ranking of Institutions on Innovation Achievements, and Apiary on Wheels. And today, with the dynamism of the government and various institutions, the country has a dominant and nourishing entrepreneurial ecosystem and stands as the sixth-largest economy in the world (Heiska et al., 2017). In a diverse land like India, the way forward to entrepreneurship growth is to work towards a more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem to include the millions of small and medium businesses operating from the informal and unregistered sector that constitutes a significant source of employment and money flow in the economy.

Social Entrepreneurship in India

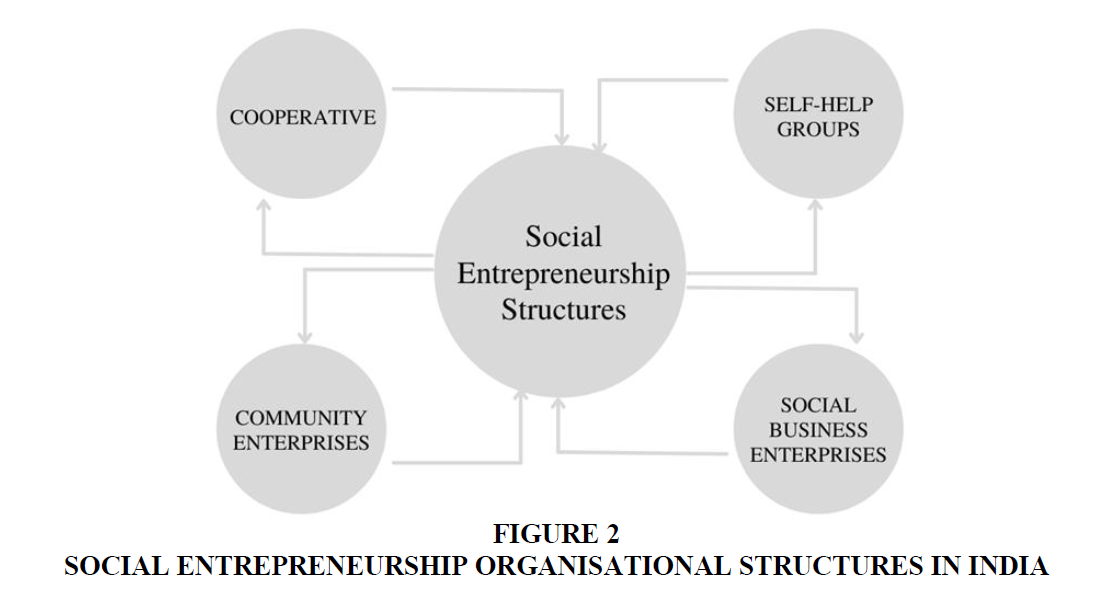

In India, social entrepreneurship is the new and enabling business model providing a framework for non-profits seeking to develop, for-profits seeking to be socially responsible, and individuals seeking to invest in organisations committed to corporate social responsibility and sustainability. Social entrepreneurship as an independent field is relatively a recent one in India. However, the phenomenon has been in practice as a whole or part of entrepreneurship in the country throughout history (Kumar, 2014). Several entrepreneurs had even run 'for-benefit' social enterprises in the country long before the word 'social entrepreneurship' was coined in the literature. Amongst the early entrepreneurs in the eighteenth century, many had broad social interests and were committed to philanthropic business pursuits (Medhora, 1965). The 'for-benefit' social enterprise model takes several forms and organisational structures in India across various sectors (Shukla, 2019). As a cooperative, community enterprise, self-help group, social purpose business, and more, to name a few examples. Amul, an Indian dairy cooperative society, founded in 1946 by Tribhuvandas Patel; Lijjat, an Indian cooperative for women workers, formed in 1959 by seven women from Mumbai, India; Aravind Eye Hospital in 1976, founded by Govindappa Venkataswamy and Thulasiraj D Ravilla; are notable precedents of social entrepreneurship roots in the country (Patankar & Mehta, 2018) Figure 2.

The 'for-benefit' social enterprises act as change agents that harness innovation at a systemic level, in turn, to bring about a change in the social equilibrium (Noboru, 2013) Given the proof of their ability to accelerate a positive social transformation and economic progress in the past, the concept of 'for-benefit' social enterprise has gained traction in the present, notwithstanding the country's vital economic and social obstacles. As India tries to strike a balance between increasing GDP growth, guaranteeing inclusive growth, and addressing concerns such as employability, education, energy efficiency, and climate change, 'for-benefit' social entrepreneurship is likely to be the next big thing (Singh, 2012). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019-20 survey data of Indian entrepreneurs shows that "86% of the people in India want to start a business to make a difference in the world". As Swiss Klaus Schwab, the founder of the Schwab Foundation, once mentioned, "India has some of the most innovative and unconventional social entrepreneurs" and, thus, the country is keen on empowering the 'for-benefit' social entrepreneurs. Unlike in the past, the countrys' present-day social entrepreneurship ecosystem has in place various financial and non-financial institutions and organisations that foster, mentor, and fund 'for-benefit' social enterprises' establishment and growth. UnLtd India, Villgro, Action for India, Deshpande Foundation, IITM's RTBI, Dasra, Upaya Social Ventures, Ennovent, CIIE, Khosla Labs, and Marico Innovation Foundation are amongst the many social incubators in India offering to support the 'for-benefit' social enterprises' with access to knowledge resources, infrastructure, technology, investment, mentorship, and other aided assistance. The large corporate entities in the country are willing to collaborate with 'for-benefit' social enterprises to meet their corporate social responsibility (CSR) goals. However, in spite of this highly prospective and nurturing environment, a majority of the 'for-benefit' social enterprises are incompetent to scale up to their full potential by reason of multiple challenges. The crucial challenges faced by the 'for-benefit' social enterprises in India include lack of a customer insight-based business plan, access to investment funding, hiring the right people, lack of policy regulations, lack of metrics for performance measurement, a balance between mission and profit-related activities, and a systematic performance evaluation system. The 'for-benefit' social entrepreneurs who can communicate their value to their beneficiaries and investors and are able to distinguish themselves from other similar for-profit businesses and non-profit organisations instil confidence in the stakeholder community and eventually become successful.

Performance Measurement in 'for-benefit' Social Enterprises in India

According to Neely et al. (2002), performance measurement, by definition, is the use of suitable metrics to quantify the efficiency and effectiveness of an enterprises activities. Performance measurement systems (PMS) originated in the business sector were initially designed for commercial, for-profit enterprises in order to compare performances over time and determine the future directions and action plans. Organizations using such an approach rely heavily on financial measures to measure their performance. Today, systems of performance measurement (metrics) are central to all organisational strategies and operations. Metrics now pervade society on a trajectory that began with the introduction of consistent reporting practices in the private sector, which now encompasses the public sector and increasingly the social enterprises' sector too. However, there are no recognised units of measured social performance or regulatory accounting procedures in the social enterprise sector to give the outcome data a comparative significance. This is largely due to the perceived difficulty in establishing a relationship between the various input components (grants, volunteers, market income, social capital, etc.) and the social outputs that constitute such social enterprises' mission aims. The number of 'for-benefit' social enterprises is on the rise and has been developing across the globe. Yet, in order to achieve progress through 'for-benefit' social enterprises, a challenge arises: measuring performance and social impact. Even though impact measurement can be rather complex and costly, it is critical for the further development of such organisations (Bulsara et al., 2015). The need to develop performance measurement tools to assess if 'for-benefit' social enterprises in India are generating value is significantly increasing cause of the following reasons. Firstly, despite its increasing prominence and piqued interest, the conception of 'for-benefit' social entrepreneurship still lacks theories and proven hypotheses to fully comprehend the integration of social and economic value generation within the same organizational framework in the Indian context. Secondly, there is no legal doctrine to define and streamline the operational guidelines for these 'for-benefit' social enterprises in India, making it impossible to build a social entrepreneurship performance index. Thirdly, as the country attracts more and more 'for-benefit' social enterprises lured by the opportunity to serve the less privileged in the country, the number and sources of potential funding have also expanded (Arogyaswamy, 2017). So has the competition to secure them. Fourthly, it is becoming increasingly critical for the 'for-benefit' social enterprises to measure and report on their social impact created in order to build credibility amongst their investors, shareholders, and stakeholders (Arena et al., 2010). Fifthly, metrics are costly but valuable since they offer the tantalising prospect of capturing complex situations in an apparently objective and impartial fashion to minimise risk and maximise return. And lastly, given the limited exposure of those running a 'for-benefit' social enterprise, measuring their performance could provide the necessary information for the social entrepreneurs themselves, their investors and stakeholders for effective decision-making to improve business operations (Arena et al., 2005). Performance measurement in 'for-benefit' social enterprises to come to be challenging as their mission-centred activities do not often get viewed in ally with their income generation activities (Smith et al., 2012). 'for-benefit' social enterprises in India operate in a diversified environment with different organizational structures in various sectors and in connection with many other for-profit businesses and non-profit organizations. This nature of heterogeneity certainly gives rise to different stakeholder expectations and metric needs for assessing performance in 'for-benefit' social enterprises (Herman & Renz, 1997). Performance measurement in 'for-benefit' social enterprises thus necessitates the consideration of a comprehensive range of objectives and results for a diverse group of stakeholders with varying interests (Kerlin, 2006). An inclusive measurement of all value outcomes may be crucial in learning which 'for-benefit' social enterprises provide the most value to their beneficiaries, investors and stakeholders and succeed over time (Harrison & Wicks, 2013). The most challenging limitation in developing such an inclusive performance measurement tool for a 'for-benefit' social enterprise is the lack of metrics to quantify, measure, and validate their collective performance in terms of financial and social return on investment. Such assumptions, however, are being challenged by a new breed of 'for-benefit' social enterprises that are developing more rigorous performance monitoring systems that increase accountability as part of their purpose to bring about systemic change in failing social and environmental situations. As a result, a tool for monitoring the performance of 'for-benefit' social businesses should include a varied range of performance indicators capable of measuring the enterprises' diverse objectives in terms of economic and social performance (Arena et al., 2015). This need reflects the necessary call to structure the performance measurement system in 'for- benefit' social enterprises to use a 'double bottom line' approach, which blends their social mission-driven strategy with a profit benefit strategy for inclusive performance measurement (Wilburn & Wilburn, 2014).

Double Bottom Line Performance Measure in for-benefit Social Enterprises in India

The growing number of 'for-benefit' social enterprises that use their business actions to benefit the community of people while making a profit reflects the need for new performance evaluation tools to hold their businesses accountable for completing their integrated social and financial goals. And what sets apart a 'for-benefit' social enterprise from its counterparts in the non-profit and for-profit sector is the integrated measure of their social and financial returns (Rubin, 2001). As mentioned in research from Bosse et al. (2009), while financial gains are vital to a 'for-benefit' social enterprises' key stakeholders, they also desire equal social value outcomes. In addition, a collective assessment of return on investment in for-profit social enterprises creates conviction in their performance results. On the contrary, the lack of a collective performance measurement excludes the 'for-benefit' social enterprise sector from the potential investment market, where social impact investors seek critical evidence for their contribution to socio-economic development (Bull & Crompton, 2006). Following this, there is a strong and growing emphasis amongst the 'for-benefit' social enterprises to develop an enterprise culture that reinforces performance measurement practices that support the fusion of social and economic goals. As a result, as a means to achieve a new assessment procedure that integrated the financial outcome and social value provided against the investment made, the concept of a double bottom line performance measure was regarded. Given by definition, a double bottom line method tries to supplement the traditional bottom line, which assesses financial performance in terms of monetary profit or loss by adding a second bottom line to measure a business's performance in terms of positive social impact. The function of a double bottom line performance measure thus is to recognise both the financial and social outcomes under one roof from running and owning a 'for-benefit' social enterprise. The necessity to adopt the double bottom line approach to its performance measurement reporting in 'for-benefit' social enterprises is increasing due to various determinants influencing the growth of social entrepreneurship in the country. This double bottom line approach performance measure has significantly become a prevailing trend in socially responsible business ventures which adhere to purpose-driven yet profit-oriented business actions. According to a research report by the Center for Responsible Business (University of California, Berkeley), while there are universally accepted accounting principles for financial return on investment (ROI), there is no comparable standard for social return on investment (SROI) accounting. In addition, financial returns are a definite measure assumed in the short run, while contradicting social returns account for an indefinite measure achievable in the long run. The performance measure resulting from incorporating a double bottom line approach reporting in a 'for-benefit' social enterprise yields a compound result of the two conventional performance measures, return on investment (ROI) and social return on investment (SROI) (Rosenzweig, 2004). Yet there is no standard assessment tool to capture the integrative outcome as a single validated performance measure. The challenge thus arises in developing a valid metric system to tally the integrative results to correspond as a uniform measure of performance assessment. By creating a new framework for performance measurement with a double bottom line approach of profit and social mission practices, the 'for-benefit' social enterprises would attract new capital from potential investors in the billion-dollar impact investment market (Kulikowski, 2012). The adoption of a double bottom line measure will indeed lead governments and consumers to recognise and support 'for-benefit' social enterprises as an equally legitimate model. The functional bodies that support the growth of 'for-benefit' social enterprises shall impose regulatory standards in order to enable the implementation of double bottom line performance measurement in 'for-benefit' social enterprises. While there are clear financial benefits to evaluating a 'for-benefit' social enterprise's performance in terms of a double bottom line measure, this method may also be significant to ensure their long-term viability. Thus a double bottom line incorporated performance measurement in 'for-benefit' social enterprises advances a win-win situation for both the enterprise and its stakeholders (Sullivan, 2003).

Conclusion

While the role of 'for-benefit' social enterprises in accelerating economic growth and impacting positive social change in the country is by now well understood, the subject matter of performance measurement entails the attention it deserves. This study objectively reviews the various positive trends and the several challenges the 'for-benefit' social enterprises encounter in the country in order for them to be fully self-sustainable and financially profitable to stay in business. In evidence, the study highlights the deep roots of the nature of dual accountability in 'for-benefit' social enterprises and its effects on performance measurement. This study thus rediscovers the many reasons to develop standard metrics to collectively quantify, measure, and validate the financial and social outcomes in 'for-benefit' social enterprises. This study briefly outlines the salient features of a double bottom line approach and its utility in 'for-benefit' social enterprises performance measurement. In conclusion, this study reinstates the necessity to incorporate the double bottom line approach to performance measurement in 'for-benefit' social enterprises in order to benefit from the current social entrepreneurial settings.

References

Alter, K. (2007). Social enterprise typology. Virtue Ventures LLC, 12(1), 1-124.

Arena, M., & Azzone, G. (2005). ABC, Balanced Scorecard, EVA™: an empirical study on the adoption of innovative management accounting techniques. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 2(3), 206-225.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Arena, M., & Azzone, G. (2010). Process based approach to select key sustainability indicators for steel companies. Ironmaking & Steelmaking, 37(6), 437-444.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Arena, M., Azzone, G. & Bengo, I., (2015). Performance measurement for social enterprises. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(2), pp.649-672.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Arogyaswamy, B. (2017). Social entrepreneurship performance measurement: A time-based organizing framework. Business Horizons, 60(5), 603-611.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei–Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: same, different, or both?. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1-22.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Bartha, Z., & Bereczk, A. (2019). Financial Viability of Social Enterprises.

Bosse, D. A., Phillips, R. A., & Harrison, J. S. (2009). Stakeholders, reciprocity, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 447-456.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Bull, M., & Crompton, H. (2006). Business practices in social enterprises. Social Enterprise Journal.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Bulsara, H. P., Gandhi, S., & Chandwani, J. (2015). Social entrepreneurship in India: An exploratory study. International Journal of Innovation, 3(1), 7-16.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits: What do you do when traditional sources of funding fall short. Harvard business review, 76(1), 55-67.

Gandhi, T., & Raina, R. (2018). Social entrepreneurship: the need, relevance, facets and constraints. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1), 1-13.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2013). Stakeholder theory, value, and firm performance. Business ethics quarterly, 23(1), 97-124.

Heiska, O., Hüsch, S., & Veabråten Hedén, A. (2017). Performance measurement in social enterprise start-ups.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Herman, R. D., & Renz, D. O. (1997). Multiple constituencies and the social construction of nonprofit organization effectiveness. Nonprofit and voluntary sector quarterly, 26(2), 185-206.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Kerlin, J. A. (2006). Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: Understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 17(3), 246-262.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Kulikowski, L., 2012. What it means to be a B Corp. TheStreet.

Kumar, K. (2014). Reviving business history in India–The way forward. IIMB Management Review, 26(1), 65-73.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Medhora, P. B. (1965). Entrepreneurship in India. Political Science Quarterly, 80(4), 558-580.

Neely, A. D., Adams, C., & Kennerley, M. (2002). The performance prism: The scorecard for measuring and managing business success. London: Prentice Hall Financial Times.

Noboru, T. A. B. E., & GIRIAPPA, S. (2013). Entrepreneurship Development in India: Emergence from Local to Global Business Leadership. Evolution.

Patankar, V. A., & Mehta, N. K. (2018). Indian Entrepreneurial Communities: The People Who Set-up Their Businesses. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 20(2), 41-49.

Rawal, T. (2018). A study of Social Entrepreneurship in India. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 5(01).

Rosenzweig, W. (2004). Double bottom line project report: assessing social impact in double bottom line ventures.

Rubin, J. S. (2001). Community development venture capital: A double-bottom line approach to poverty alleviation. System, 121, 154.

Shukla, M. (2019). Social entrepreneurship in India: Quarter idealism and a pound of pragmatism. Sage Publications Pvt. Limited.

Singh, K. & Sharma, M., (2019). Social Entrepreneurship in India: Opportunities and Challenges. International Journal of Engineering Science and Computing (IJESC), 9(8), 23619–23623.

Singh, P. (2012). Social entrepreneurship: A growing trend in Indian economy. International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology, 1(3), 44-52.

Smith, B. R., Cronley, M. L., & Barr, T. F. (2012). Funding implications of social enterprise: The role of mission consistency, entrepreneurial competence, and attitude toward social enterprise on donor behavior. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(1), 142-157.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Sullivan Mort, G., Weerawardena, J., & Carnegie, K. (2003). Social entrepreneurship: Towards conceptualisation. International journal of nonprofit and voluntary sector marketing, 8(1), 76-88.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Thakur, U. (1972). A study in barter and exchange in ancient India. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient/Journal de l'histoire economique et sociale de l'Orient, 297-315.

Wilburn, K., & Wilburn, R. (2014). The double bottom line: Profit and social benefit. Business Horizons, 57(1), 11-20.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 16-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-22-11276; Editor assigned: 16-Feb-2022, PreQC No. AAFSJ-22-11276(PQ); Reviewed: 21-Fab-2022, QC No. AAFSJ-22-11276; Revised: 24-Fab-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-22-11276(R); Published: 28-Feb-2022