Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 4S

Proposed Strategy for Micro-Enterprise Development A Case of Immigrants and Locals in Tembisa and Ivory Park

Francinah L Phalatsi, University of Johannesburg

Bulelwa Maphela, University of Johannesburg

Abstract

Spaza shops, which are ‘small convenience stores’, play an integral part in many township economies within low-income earning societies in South Africa. These micro-enterprises act as providers of basic groceries and home essentials to those societies. Recent studies and reports show that there has been a dwindling case of South African-owned spaza shops, while those operated and owned by foreign nationals are reportedly growing and increasing in volume in certain township areas. Trade practices such as ‘coopetition’ – the use of social networks and collaborating with competition – has been cited as the differentiating factor that gives foreign national spaza shop owners the competitive advantage. Aim: The purpose of this study was to explore how local government can assist South African-owned spaza shops to be sustainable and grow through the local economic development (LED) agenda. The aim, therefore, was to create a practical strategy for LED practitioners to enable competitiveness and promote the sustainability of South African spaza shops in the Tembisa and Ivory Park townships within the Ekurhuleni and City of Johannesburg municipalities. Methods: A concurrent mixed-method design was deemed appropriate, using both a survey questionnaire and semi-structured interviews to collect primary data. Through corroborating insight, lessons and results of trade practices and the notion of coopetition by foreign-owned spaza shops were explored. Results: Key findings showed that coopetition is a myth, and foreign nationals use social networks to their advantage in running sustainable spaza shops and dominating the market. Foreign national citizens indeed dominate the spaza shop market, yet this is not evident in local government’s plans, as proven recently by gaps identified during the COVID-19 relief plans. Lastly, socio-economic challenges such as unemployment and crime persist, with spaza shopsnot predominantly employing South Africans as literature would suggest. Conclusion: The paper concludes with a call for active and intentional engagement by local government and LED practitioners. A pragmatic participatory “bottom-up” approach is recommended through the efficient use of systems thinking, coupled with a two-pronged approach to policy that addresses having a regulatory approach for fair and standard business frameworks and relevant key stakeholder engagement.

Keywords

Coopetition, Micro-Enterprise, Migrant Entrepreneur, Social Networks, Spaza Shop Market, Township Economy.

Introduction

The development of informal economies and promoting township economic development is one of the key focal points within the second local economic development (LED) pillar, which was the focus of this study. LED has been defined by the South African National LED Framework as “a participatory process in which local people from all sectors and communities work together to stimulate local commercial activity, resulting in a resilient and sustainable economy” (Walaza, 2017).

The informal sector is a feature of almost all of South Africa’s local economies. It is particularly significant in the rural, township, and peri-urban economies, where many derive livelihoods from avenues such as spaza shops, roadside vending, and rural craft businesses. It is primarily characterised by significant dependence on local resources, family proprietorship, small-scale operation, and the use of intensive labour. In many township economies within lowincome earning societies in South Africa, micro-enterprises – specifically spaza shops, which are ‘small convenience stores’ – play an integral part as providers of basic groceries and home essentials to those communities (Chebelyon-Dalizu et al., 2010). These shops are also dominant within the township retail landscape across different locations (Ligthelm, 2008). Spaza shops owned by South Africans are reported to be dwindling; with rising failure rates they have also become less competitive (Hartnack & Liedeman, 2017; Ligthelm, 2011). Competition from larger retailers and corporates from outside the township making inroads into the townships is one of the top three obstacles spaza shop owners across numerous studies face (Woodward et al., 2014). Strydom (2015) emphasised the “level of competition between informal businesses and formal businesses has a major negative effect on the business survival of the informal retailers”.

On the contrary, spaza shops operated and owned by foreign nationals are reportedly growing and increasing in volume in certain townships and areas (Charman et al., 2012). Spaza shops owned by foreign nationals’ price competitiveness is one of the principal contributors to their competitive advantage. It is achieved through social networks and bulk buying (coopetition), which is vital in low-income earning areas such as townships. Results from a study conducted in Alexander township suggest spaza shops owned by South Africans do not use social networks to form coopetitive partnerships (Hare & Walwyn, 2019).

Businesses in the Small, Medium and Micro-Enterprises (SMMEs) sector are considered key drivers of employment, but are failing at a rate of 75 per cent (Bruwer, 2017). The unemployment rate in South Africa was reported to be a staggering 30.1 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 (Statistics SA, 2020). Simultaneously, the rate of entrepreneurship activity, calculated by “Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity” (TEA), dropped by 25 per cent between 2015 and 2016, ranking South Africa 28th out of 32 efficiency-driven economies (Herrington et al., 2017).

This study’s main objective was to explore how local government within the LED agenda can assist South African-owned spaza shops to be sustainable and grow. This study aimed to do so by exploring the levels of trade practices among a cohort of spaza shop owners, their level of comfort to form social networks (coopetition), and how local government can assist these businesses to be sustainable from a bottom-up approach. A bottom-up approach is a consultative and autonomous style of making decisions where key stakeholders, in this instance, the spaza shop owners, are consulted. Their participation is encouraged in solving the realities and challenges they face in their everyday line of work. Such a project is vital with regards to a variety of challenges concerning township dynamics, namely unemployment, economic growth, economic inclusiveness, and social cohesion.

Literature Review

Significance of Micro-enterprises in Township Economy

According to Section 1 of the National Small Business (NSB) Act 102 of 1996, as amended by NSB Act 26 of 2003 and 29 of 2004, small businesses can be classified into four separate clusters, namely survivalist, micro, very small, small and medium (SMME). The broad definition of micro-enterprise in the NSB Act is “when turnover is less than the value-added tax (VAT) registration limit (that is, R150 000 per year). These enterprises usually lack formality in terms of registration. They include, for example, spaza shops, hair salons, and household industries. They employ no more than 5 people” (Republic of South Africa, 2004). Though individual incomes are low, Statistics South Africa estimates that 5.2 per cent of South Africa’s GDP comprises economic activity from informal enterprises (Statistics SA, 2016). In comparison, the informal sector accounts for 16.7 per cent of employment in the country (Rogan & Skinner, 2017).

Markets and business activities based in the townships are clustered under “Township Economy”. Entrepreneurs run these businesses from the township to primarily meet residents’ needs within and beyond the township precinct. Hence, the term “township enterprises”, to distinguish them from enterprises operated outside the township periphery (Province, 2014). These township enterprises typically operate from a high degree of informality and are diverse in terms of providing various products and services required by the township market. Hence, the township economy has been on the political agenda of ‘revitalising’ the township economy in South Africa (Charman, 2017).

Micro-enterprises are valued sources of employment creation, a significant catalyst in alleviating poverty and promoting economic growth (Ligthelm, 2008; Mthimkulu & Aziakpono, 2015). In South Africa, in the year 2000, 2.7 per cent of the country’s retail trade was contributed by spaza shops, which amounted to R7.4 billion (Lighthelm, 2005). Spaza shops thus play a significant socio-economic part by creating job prospects, offering credit purchases to their customer base in certain instances, and creating economic activity in locations where minimal such opportunities exist (Roos et al., 2013). If or when profitable, these micro-enterprises provide financial support and income for the owners and employees, as well as their immediate and extended families, and in certain instances, for several other poor people within the greater community where they operate (Liedeman et al., 2013).

Formal vs Informal Economy

The informal economy is a term that is often used to describe economic activities that take place outside the formal economy, either as a supplementary or alternative economic activity for income. Petersen, Thorogood et al. (2019) define the informal economy as that which incorporates enterprises that are not registered and where individual proprietors dominate, both geologically and within the value chain of their products and services. Portes and Haller (2010) further describe informal economic activities as those not regulated nor recorded for taxation purposes.

According to Vanek et al. (2014), the sub-Saharan Africa informal economy employs over one-half of non-agricultural vacancies, totalling 66 per cent of the overall economy. The sub-Saharan African informal economy is also noted to have the highest entrepreneurship participation globally, with 26 per cent of its labour force clustered as entrepreneurs. Latin America follows as a close second at 23 per cent, and North Africa and the Middle East at 11 per cent, respectively (Williams, 2015).

Although the informal economy in South Africa is a small contributor to GDP, a study in Cape Town determined that informal micro-enterprises promote the economic impact that is localised and represents the city’s greatest possibility for jobs related to the number of people (Petersen & Charman, 2018). Several authors have undertaken analysis mapping exercises of these businesses in townships across South Africa, which have been graphically represented in several publications (Charman & Petersen, 2015; Liedeman et al., 2013). Moreover, Valodia, et al. (2005) stated that retail trade constitutes half of all informal employment and business activities in the country.

The informal economy has also been relatively attractive to migrants who find it easier to enter and respond to their economic needs. Losby et al. (2002) argued that migrant groups often enter the informal economy for two reasons: First, undocumented migrants find it opportune to participate in informal economic activities to reduce any likelihoods of getting deported or arrested. Second, those migrants who are documented often face challenges related to cultural barriers, skill sets, or language that may hinder their prospects of finding employment, which results in them taking part in informal economic activities (Newland et al., 2019).

Migrants and South Africa’s Informal Economy

The 2013 population report by the United Nations revealed that 232 million (3%) of the global population were international migrants who moved across borders for periods longer than 12 months (Münz, 2013). People migrate for a myriad of reasons. A group of international migrants could comprise of skilled workers seeking new opportunities, asylum seekers fleeing political unrest from their own countries, or those trying to find new land without the plight of natural disasters, among many other reasons.

South Africa is central to Africa’s migration and has the largest population of migrants from Africa (Statistics SA, 2014). According to the 2011 census report, 75 per cent of migrants living in South Africa are originally from other African countries; 68 per cent of these migrants are from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region (Meny-Gibert & Chiumia, 2016; Statistics SA, 2016). Migrants from all over the world are active participants in the informal sector, mostly motivated by some of the socio-economic adversities faced by South Africa, such as unemployment, poverty, and inequality.

Several studies on migrant economic activity in South Africa and abroad have alluded to how the informal economy entrepreneurship landscape has changed as a result of migrant participation (Charman et al., 2012; Liedeman et al., 2013; Radipere & Dliwayo, 2014). Studies on migrant economic activities have pointed to how migrant entrepreneurs form ethnic groups in their host countries (Golden et al., 2011), with ethnicity as one of the most distinguishing factors (Nijkamp et al., 2011). “Ethnic entrepreneurship” is defined by Waldinger et al. (1990) as “a set of connections and regular patterns of interaction among people sharing common national background or migration experiences”. It has also been reported that most migrant entrepreneurs participate in informal retail trade or service largely in the form of mini retail grocery stores, such as spaza shops and ‘house’ shops (Rodgerson, 1998).

Evolution of Spaza Shop Market

Literature reveals that there has been considerable change in the informal retail sector’s demography and competitive landscape over the past 20 years; since the dawn of democracy in South Africa in 1994. According to the 2018 Sustainable Livelihoods study, 54 per cent of all informal micro-enterprises in townships are drink and food-related, with the food economy forming the basis for women with dependants to establish a micro-enterprise (Petersen et al., 2019). Hence, the informal economy’s backbone remains food and drinks, as depicted in Picture 1. Moreover, more than two-thirds of these informal micro-enterprises are in the form of ‘house shops’ or ‘spaza shops’, and play a noteworthy part in food security, self- employment, and social unity (Charman, 2017).

Research findings from a study conducted between 2010 to 2015 by Charman et al. (2017), revealed the extent of foreign national entrants’ dominance as spaza shop owners in this market, including people from Ethiopia, Somalia and Bangladesh. These individuals were found to be operating and owning the majority (an estimated 80 per cent) of spaza shops in some townships. Similarly, Das Nair and Dube (2015) estimated that 70 per cent of spaza shops are owned by foreign nationals. Furthermore, Hartnack and Liedeman (2017); Ligthelm (2013), argue that spaza shops owned by South Africans struggle because of low competition levels and higher resource input costs (goods & labour). These challenges are related to South Africans’ hesitancy to use social networks and create coopetition partnerships, similar to those of spaza shops owned by foreign nationals.

Parallel to foreign nationals’ entry to the spaza shop marketplace, there has been substantial development in corporate South Africa’s share of the market in serving township communities (Mathe, 2019). According to Scheba and Turok (2020), supermarkets in Philippi, in the Western Cape, accommodate 65 per cent of township households, increasing the price competitiveness pressure on spaza shops. However, spaza shops owned by foreign nationals are an exception to this trend of micro-enterprises failing; in fact, they are rising in numbers. As a result, the majority of spaza shops in certain townships and localities are foreign-owned (Charman et al., 2012).

Foreign-owned Spaza Shops

Promoters of the new era of spaza shops owned and operated by foreign nationals argue that there are benefits to new business methods, including a decrease in prices for consumers and improved customer service (Gastrow & Amit, 2013). Ibrahim (2016) argues how the Somali spaza shop owners’ competitive business methods have improved service to consumers and expanded the range of products in comparison to the South African incumbents. In addition, results in a study conducted by Gastrow (2018) indicate that these shop owners have enabled township residents and previous South African spaza shop owners to become landlords – none of the spaza traders they interviewed owned the properties from which they traded; instead, they leased their premises from South Africans, many of whom were previously spaza shop owners.

Petersen et al. (2019) determined that the shop assistants reported working seven days a week, more than 15 hours a day, and grossing as little as R400 a month. Some of them claimed to work towards being shareholders, yet there were no written contracts, and all worked for wages paid in cash. This, coupled with setting up local distribution networks, resulted in reduced prices due to reduced economies of scale, making these spaza shops more price competitive (Liedeman et al., 2013). Another study in the Western Cape, on Somali owned spaza shops, revealed that their “top trade practices” comprised of collectively purchasing stock, sharing delivery costs, and collectively investing in several spaza shops (Gastrow & Amit, 2013).

Such strategies have contributed to the changing demography of the spaza shop market, giving foreign nationals competitive advantage. This view is corroborated in a study by Charman and Petersen (2015), stating that SA-owned spaza shops in Delft Cape Town declined from 50 per cent to 18 per cent between 2010 and 2015. They further report how spaza shops owned and operated by foreign nationals should not be considered businesses that stand alone; instead, they are role-players at the bottom of the value chain, connecting retail shops of larger grocery stores that are integrated vertically. However, little is known about their financial retail and stock arrangements.

There has been rising concern and requests for the moderation of the dynamic changes in the spaza shop sector; the demographic changes disrupt and erode the local social fabric of the township communities. Charman et al. (2012) argue how this trajectory of foreign-owned spaza shops harm South African women who were the original operators and owners of spaza shops historically, and now bear the brunt of businesses closing down. Historically, the spaza market had low barriers to entry which enabled women and the poor to operate shops within their homes (Liedeman et al. 2013). The current phenomenon then renders these women without a source of income, perpetuating the poverty levels and socio-economic challenges in townships.

Coopetition

Coopetition is a business strategy where enterprises cooperate within networks and simultaneously compete in the same market, bringing numerous benefits to sole proprietors (Gastrow & Amit, 2013; Charman, et al., 2012; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2014). It is a strategy widely used by micro-enterprises trying to compete against large retailers who dominate low margin with high volume markets (Bengtsson & Kock, 2000). Such strategies are widely used and common within marginal communities and among the vulnerable, such as immigrants. According to Liedeman et al. (2013), “clan-based social networks played a critical role in enabling a more competitive business model”.

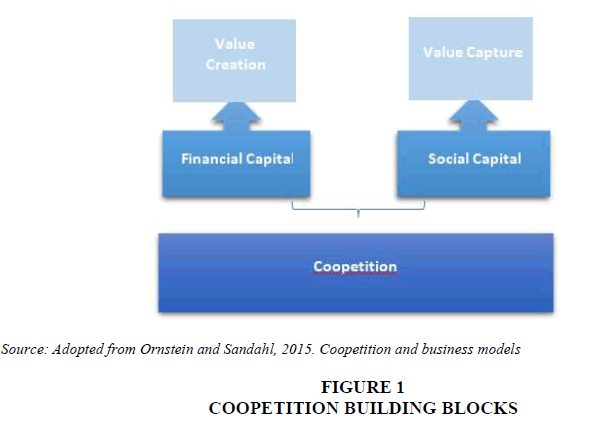

Furthermore, Khosa and Kalitanyi (2014) emphasised the significance of social networks in the initial establishment and growth stages of enterprises, and they encouraged the necessary support should be provided. Charman et al. (2012) contributed by arguing that social capital evolves into various forms of support besides financial capital, such as affordable rent, having security and protection, business advice, and access to more affordable labour from newly arrived compatriots (shows in Figure 1).

Literature has already postulated how spaza shops operated and owned by foreign nationals use these social networks to remain price competitive by employing cheap labour, therefore, keeping their overhead expenses low, while accessing social capital and purchasing in bulk (Gastrow & Amit, 2013; Petersen et al., 2019; Radipere, 2012). Several theoretical frameworks have been used to examine and try to explain this concept of coopetition, including concepts from the resource-based view, network theory, and game theory (Gnyawali & Park, 2009), the migration theory (Woodruff & Zenteno, 2007), and the inter-organisational dynamics theory (Padula & Dagnino, 2007). However, the majority of these frameworks were based on technology-led industries or enterprises, with limited application to micro-enterprises (Hare & Walwyd, 2019).

From a different perspective, a study conducted by Woodruff and Zenteno (2007) shared insights that migrant community members often form and work within strong social networks for the benefit of the collective. This gives them greater access to financial and social capital, higher profits, improved capital-output ratios, and more significant profit margins. With limited examples of studies of coopetition, it is therefore evident that it is emerging, and additional studies are required, especially within the micro-enterprise sector (Gnyawali & Park, 2009; Tidström, 2008; Bengston & Kock, 2000; Zakrzewska-Bielawska, 2014).

The literature on the strength, scale, and scope of networks within the spaza shop sector in South Africa, where foreign-owned spaza shops are concerned, is gradually emerging and coming to the fore. However, it is suggested that South African spaza shop owners steer away from any forms of collective purchasing of stock or assets (Tladi & Miehlbradt, 2003; Liedeman et al., 2013). This was corroborated by Hare and Walwyn (2019), who revealed how the majority of the spaza shops in their cohort of respondents in Alexander township did not employ additional labour, nor did they form or use their social networks to build coopetitive relationships. This raises the question: what prevents South African spaza shop owners from adopting similar coopetition trade practices as their successful foreign counterparts?

Led and Township Economy

The second core policy pillar on which this study is underpinned, “Developing Inclusive Economies”, has relevance to the eighth Sustainability Development Goal (SDG), which aims to encourage inclusive and sustainable economic growth, productive and full employment. Achieving the SDGs by 2030 will largely depend on progress made in LED, especially in economic sectors which can drive inclusive LED. The cornerstone of sustainable LED is strategic planning, which involves the astute use of resources, integration of values, and forwardthinking (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2005).

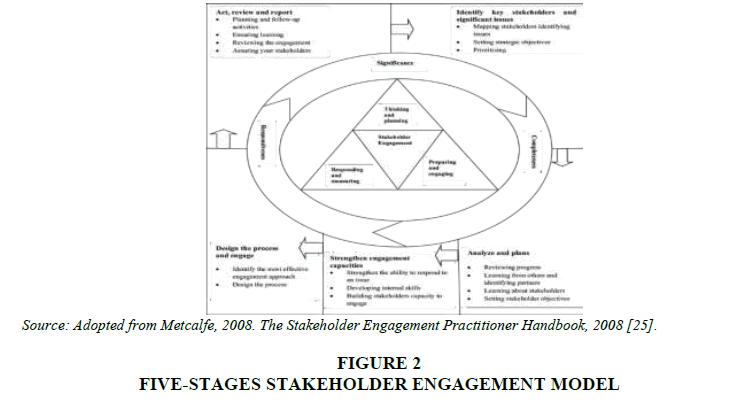

Strategic planning is central to academic research for public organisations as a tool to deal with multifaceted environments, to achieve higher local government objectives, and attaining a better democracy (Bryson et al., 2013). In local government, it also includes the process of identifying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT analysis) of the municipality’s organisational office to be able to define its vision, objectives, and mission. It is used to identify key participants and establish strategies to progress efficiencies and execute on deliverables (Bryson, 2004). An engagement method that is participatory in nature, is depicted in Figure 2. Participation that encapsulates all key stakeholders’ engagement in a democratic manner results in responsive LED and monitoring that is continuous and holds all role-players to account.

However, many local governments’ strategic plans are window dressing exercises with policies in place, but lacking implementation (Nel, 2001). The analysis of such processes is therefore important to prove that successfully introducing strategic plans within municipalities does not only depend on innovative and technological designs on paper, but more on a participative methodology, execution, and constant monitoring of an inclusive strategic plan.

Policy in Action

COVID-19 has revealed that many spaza shops across all township in South Africa are not registered, nor are they under the radar of local municipalities (Hwacha, 2020). As previously noted, the existence and operation of these small convenience stores reflect an existing demand for such retail services within township residential areas, especially in areas where residents are less mobile and current business nodes are on the outskirts (Scheba & Turok, 2020; Hartnack & Liedeman, 2017; Gastrow & Amit, 2013; Department of Small Business Development (DSBD), 2020).

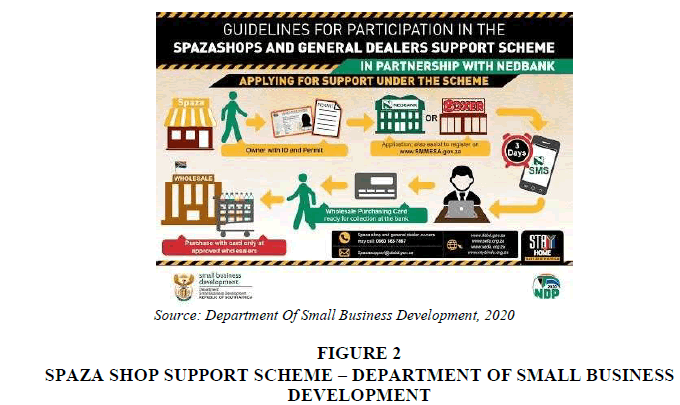

On the 5th of March 2020, South Africa recorded its first case of coronavirus and, seemingly overnight, the Covid-19 pandemic hit the South African shores. The Department of Small Business Development (DSBD) had to step in with an overall approach in efforts to standardise and assist SMMEs across the formal and informal economies. The guidelines stated that only spaza shop owners and general dealer owners with valid trading permits (including temporary) or business licences in terms of a general dealer, who are South African, would qualify to apply to continue trading (DSBD, 2020).

Many would argue that it was a progressive approach to strengthening the retail trade ecosystem within which spaza shops operate; however, most spaza shop ownership in South Africa belongs to foreign nationals. There was thus widespread criticism over this announcement, with critics labelling it as unconstitutional and xenophobic. As a result, Minister Khumbudzo Ntshavheni retracted her previous statements on the 6th of April 2020, and indicated that all spaza shops could operate during the period of lockdown “irrespective of the nationality of the owners” (Hwacha, 2020).

A recent investigation by the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation also revealed that the majority of spaza shops are informal by choice (Petersen et al. 2019), with larger and wealthier operators upstream; they have intentionally embraced the informality to avoid regulations. One of the trade practices criticised in that study was labour laws, with evidence from their sample cohort expressing over 15 hours of labour per day, with no off days, for a low monthly income (Petersen et al. 2019). Moreover, inexpensive labour practices have been noted in several other studies of this informal market (Gastrow & Amit, 2013; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2014). The findings of these studies point to the need for the DSBD and the government at large to enact legislation that is fair, simple to understand and execute, and that will not allow for the intentional avoidance of regulations.

Research Design and Methodology

This study took on a critical realism epistemological position. This acknowledges complex and multiple realities that can be experienced, reflecting the aim of this research to describe these realities as experienced by spaza shop owners in South African townships (Couch, 2016). The answers to the research questions involved complex human issues based on current literature, such as belief and value systems, insight into trade practices, working together as a collective, and the burden of history and legacy (Hare & Walwyn, 2019).

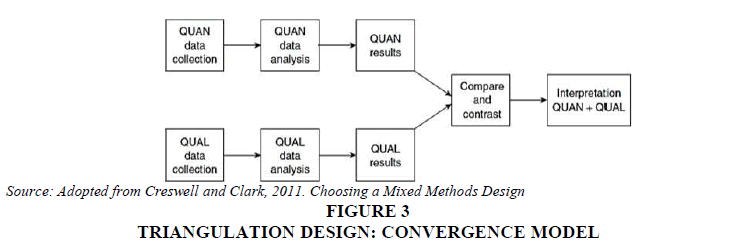

According to Myers and Newman (2007), the methodology influences how the researcher collects data. Therefore, to investigate these possibly sensitive human matters and obtain a solid set of responses, a concurrent mixed-method research approach seemed appropriate, using both a survey questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The participants included foreign national and South African spaza shop owners from Tembisa and Ivory Park as the population for this report. The unit of analysis, therefore, was the spaza shop owners.

This was a cross-sectional study that followed the traditional convergence model (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011) (refer to Figure 3). Therefore, data were collected over a short period. In line with this model, the study separately analysed and gathered data where two sets of outcomes were joined through contrasting and comparing during the interpretation stage (Tashakkori et al., 1998). The SurveyMonkeyTM tool was used to design, collect, and analyse the survey data. The semi-structured interviews were analysed with ATLAS.ti (software) using a set of coding themes.

Results and Discussion

The participants’ demographic profile is presented in Table 1.

| Table 1: Profile Of Participants | |

| Parameter | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male Female |

77 13 |

| Age (years) | |

| <25 26-55 >55 |

18 67 5 |

| Nationality | |

| South African Ethiopian Somalian Bangladeshi Other (less than 5 each) |

16 46 7 8 13 |

Summary of Findings

A summary of the responses to the research questions is presented in Table 2. Further details are given in the sections that follow the table.

| Table 2: Summary Of Responses To Research Questions | |

| Research Questions | Summary of Responses |

|---|---|

| SQ1) What are the trade practices used by existing foreigner and South African spaza shop owners in Tembisa and Ivory Park? | South African spaza shop owners tend to be sole owners, with family members who assist and provide for their labour resource needs. Foreign national spaza shop owners deal within partnerships, mainly social networks made up of friends and family and employ within those circles as well. The majority of spaza shop owners and people employed in spaza shops are male. |

| SQ2) How do spaza shop owners view the use of social networks and coopetition? | While some spaza shop owners admitted to having a friendly competition with other spaza shops in their area, the idea of collaborating with competitors to bulk-buy stock together and share trade practices (coopetition) does not take place. South African-owned spaza shops cited not having other South Africans close by to potentially collaborate and work with, while foreign national spaza shop owners worked within their social networks, made up known of friends and family, usually from the same ethnic background. |

| SQ3) How can local government assist existing spaza shop owners in the Tembisa and Ivory Park townships to sustainably grow their enterprises? | The top three things cited as requirements from local government were: 1) capital to grow business; 2) security and protection against crime; and 3) assistance with registering the shop. |

General Background: Business Overview

Of the overall 96 study participants, 93 per cent were foreign national spaza shop owners, corroborating literature findings of dwindling South African-owned spaza shops. With the majority of the spaza owners having employees, this speaks to the creation of jobs. However, of the shops that had employees, a majority were male and mostly foreign nationals. This is contradictory to claims made by Tawodzera and Chikanda (2016), who argued that foreign national spaza shops primarily hire South African women.

Furthermore, there is an overwhelming number of male spaza shop owners (87%) in comparison to female spaza shop owners (13%). Charman et al. (2012) argue how this trajectory of foreign-owned spaza shops harm South African women who were the original operators and owners of spaza shops historically, and now bear the brunt of businesses closing down. All of the female spaza shop owners (12) were South African, and 75 per cent did not have employees. One interview participant said she relied on assistance from her children at times: 4:34 “Haven’t employed anyone, my kids help me”.

Theme: Trade Practices, Customers and Suppliers

Participants were asked about customer preferences and what they consider to be the competitive advantage that keeps their customers coming back and choosing them over their competitors. Price, quality of products, and customer service were the top three options cited overall. Through the use of their social networks and the ability to keep overhead expenses low, foreign-owned spaza shops are able to reduce their prices (Donaldson, 2014; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2014). According to Hare and Walwyn (2019), numerous studies have shown that South African spaza shops were relatively more expensive than their foreign national counterparts. Part of the financial assistance and knowledge imparted by social networks is to provide trade finance to members of their network who are of similar ethnic origin and background, as well as sharing supplier contacts with new shop owners (Essa, 2019).

Theme: Social Networks and Coopetition

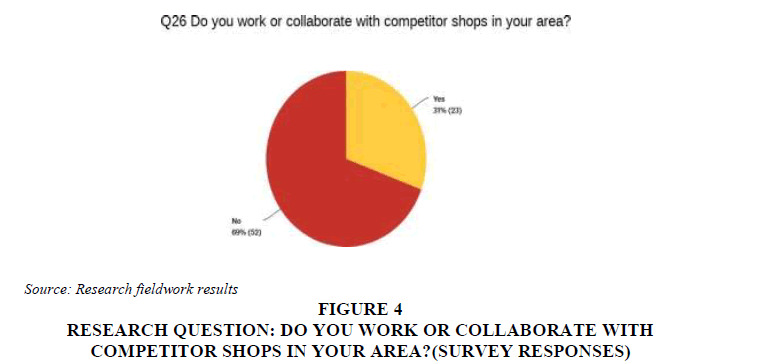

Previous studies have shown that spaza shops owned by foreign nationals form coopetitive relationships to employ labour, access capital and bulk purchase stock, empowering them to have a competitive advantage over their South African counterparts (Liedeman et al. 2013). However, the results of this study showed that spaza shop owners in Tembisa and Ivory Park were not willing to engage in coopetitive relationships with their competitors (refer to Figure 4).

Figure 5:Research Question: Do You Work Or Collaborate With Competitor Shops In Your Area? (Survey Responses).

This aligns with Hare and Walwyn’s (2019) findings from a study conducted in Alexander township, suggesting South Africans do not use social networks to form coopetitive partnerships. However, the foreign national spaza shop owners were also not promoting collaborative dealings with their competitors. This is echoed by results of the study conducted by Essa (2019), which reported that migrant entrepreneurs from Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh participate in social embeddedness, but for reasons that do not involve financial and business assistance.

Findings from the fieldwork showed that none of the South African spaza shop owners used their networks to build coopetitive relations. However, one participant said she sometimes borrowed some essential items such as flour from other spaza owners if she ran out. She was unconcerned with the competitor’s nationality from whom she would borrow. Such interactions are examples of shallower relationships and not the coopetitive type that literature argues would be beneficial to them. On the contrary, the majority of the spaza owners were involved in partnerships and helped raise values of trust, mutual benefit and commitment.

Some participants cited receiving funding from friends and family to establish their enterprises, with no expectations in return for the assistance provided. All participants were hesitant about engaging in bulk buying with their competitors but expressed having partnerships that were more effective and profitable than bulk buying. Most of these partnerships were with family members and a few friends from the same community, usually from ‘back home’. It would appear that there is no trust to engage with any competitor, regardless of nationality. Thus, it is avoided, except in rare instances when suppliers announce discounts and some competitors are in urgent need of ‘borrowing’ stock to satisfy their customers.

Theme: Local Government

Many spaza shop owners did not know the jurisdiction of the municipalities under which their shops operated and who their local councillor was, illustrating that local government should review its township revitalisation strategy. Of the survey participants, 83 per cent did not know their community leaders, while others cited having worked with them on some social outreach activities.

The South African government has placed considerable importance on the role of SMMEs in alleviating poverty, creating jobs, and positively contributing to economic growth. This is evident in terms of the SMME sector’s development being listed as one of its priorities since 1995 (Ligthelm, 2008). However, some of the external factors that could lead to spaza shops failing are out of the owners’ control; these include the macroeconomic environment, government policy, bureaucratic corruption, and the political situation in the country (Ahwireng- Obeng & Piaray, 1999; Mthimkhulu & Aziakpono, 2015).

Petersen et al. (2019) argued that the government failed in ensuring informal enterprises’ regulatory compliance while succumbing to pressures from corporate South Africa and the power of supermarket and shopping mall developers. At the same time, Ligthelm (2008) argued how the local government had missed the mark in providing relevant training programmes and supporting spaza shop owners. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed irregularities in the system with what constitutes a compliant spaza shop and who should receive relevant government support. Programmes are designed to assist ‘South African’ spaza shop owners, yet foreign nationals now operate the majority of this market.

Conclusion

South Africa’s demographic profile has been gradually changing since the country is central to the migration trend in Africa and hosts a significant population of migrants from Africa (Segatti & Landau, 2011). Several authors have encouraged this change, citing the benefits of the new business methods and undertakings by foreign national spaza shop owners, improved price options, and customer service (Gastrow & Amit, 2013; Ibrahim, 2016). In contrast, several other authors have cautioned this change and argued for the need to moderate the dynamic changes in the spaza shop sector, emphasising the impact of this trajectory on the social aspects within communities (Charman et al., 2012). However, migrants from all over the world are active participants in the informal sector. In South Africa, they are mostly motivated by some of the persistent socio-economic challenges that exist within townships and the country as a whole, such as unemployment, poverty, and inequality.

Based on the general findings of shop owners’ background, trade practices and the use of social networks, South African-owned spaza shops cannot effectively compete with their foreign national counterparts who operate within efficient partnerships in their social networks that are better-resourced. They are also unable to grow their enterprises. However, 97 per cent of foreign national spaza owners are paying rent and citing their landlords as South African citizens; these results suggest that those who previously closed down their shops have now branched into receiving rental income, as noted by Gastrow (2018). Other major challenges that spaza shop owners face are lack of business knowledge and access to markets, alongside the generally high levels of crime and the lack of money to purchase stock.

South African spaza owners predominantly work alone as sole owners, while foreign national spaza owners operate within partnerships. Trust, mutual benefit and commitment are the three values that the spaza owners consider most significant when considering or embarking in partnerships. The majority of spaza shops were operated and owned by foreign national men. In contrast, the majority of the South African shops were operated by women, as suggested in the literature. The price of products, alongside good customer service, is a competitive advantage differentiator for customers. Customer service and price are thus the two most important factors in terms of both customer and supplier preferences.

While coopetition was proven to be generally non-existent within the cohort of chosen spaza shops in Tembisa and Ivory Park, partnerships in the form of social networks made up of friends and family appeared an efficient strategy for foreign national spaza shop owners. Charman et al. (2012) argued that social capital evolves into various forms of support, besides financial capital. These include affordable rent, having security and protection, business advice, and access to more affordable labour from newly arrived compatriots. However, lack of trust, communication barriers, and limited knowledge of the mutual benefit of coopetition were some of the reasons given that prohibit such a business strategy being adopted by all spaza shop owners, regardless of their nationality (Essa, 2019).

While the concept of township revitalisation has gained traction within the political arena and LED, as detailed in the second pillar of the National LED Framework, the visibility and role of LED practitioners in this study were not understood. The key drivers within the second LED pillar that this study focussed on entailed developing informal economies and promoting township economic development. It is evident from the results of this study that although the community leaders were generally known, there was an astounding lack of knowledge of who the local councillor is and within which municipality they were operating.

The South African government has placed considerable importance on the role of SMMEs in alleviating poverty, creating jobs and positively contributing to economic growth. Because of such expectations and anticipated outcomes from SMMEs, it is vital for local government and LED offices to establish practical strategies relevant to the current spaza market dynamics, regardless of who the key role-players are. Factors outside of the spaza owners’ control, such as the macroeconomic environment, government policy, bureaucratic corruption and the political situation in the country, need to be curbed by pragmatic, efficient and relevant LED strategic policies and tactical plans (Ahwireng-Obeng & Piaray, 1999; Mthimkhulu & Aziakpono, 2015; Petersen et al., 2019).

Recommendations

The significance of the spaza shop market and the reliance on the role this sector plays within the township economy is crucial, not only for the township economy but also for the entire economy at large. Thus, active and intentional engagement from local government and LED practitioners is required. Increasingly, attention now needs to gravitate to the undertakings of the Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) value chain and business practises within the spaza shop market. Key stakeholder management, beginning with the spaza shop owners and then filtering through to all other role-players, should be embraced; a ‘bottom-up approach’ as previously defined.

The suggested interventions by policymakers:

Regulatory approach for fair and standard business framework

There should be a fair, standardised and seamless process for registering spaza shops. The tensions between South African spaza shop owners and foreign national spaza shop owners increase with the perception of lack of documentation and legal status among foreign national spaza shop owners (Losby et al. 2002). Policy and LED practices should address the linkages between the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) and the DSBD, where spaza shop registration takes place. Additionally, the role that the informal market plays in a spaza shop’s journey of growth and potential formalisation should be normalised. This will require intentional engagement with the informal market with processes that enhance the path to regulatory compliance that is required for a standard business framework. Furthermore, a pragmatic and realistic approach to policy processes is required that address the macroeconomic environment dynamics and shocks, as seen during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Effective engagement of the key stakeholders

Participation within the Integrated Development Planning (IDP) is significant because it secures buy-in from all key community members and stakeholders, and it gives everyone the right to take part in the decisions that directly affect their living conditions (Sanoff, 1999). The close cooperation and alignment between those implementing projects, the community, and relevant business stakeholders could lead to the effective implementation of strategies and projects (Mohan, 2002).

According to a United Nations (UN) report, ‘participation’ is defined as people sharing in benefits and being included in decisions across all society levels (Mohan, 2002). It infers an engagement with the surroundings and those that live in it. Through a participatory process, members of the community could identify with their surroundings and their neighbours. According to Healey (1997), this collaborative spirit among residents, small and microenterprises, could provide solutions and opportunities to resolve the challenges of daily life.

Within the spaza shop market and ecosystem, spaza owners, consumers, suppliers from townships, suppliers from organised businesses, regulators, residents, and LED practitioners coexist. Against the backdrop of the participatory method, the proposal herein is to promote this method within the Township Economy Revitalisation Strategy (TERS), from its inception and not only after setting the strategic agenda.

Finally, and critically, the LED office within local government must more effectively engage in the systems-thinking approach of collaborating with their counterparts in departments that have an impact in their specific field of focus. Based on the results of this study and recommendations made above, linkages between the DHA and DSBD need to be made to promote fair and standard business practices within the spaza shop market. This may seem obvious and potentially non-innovative in the current climate of a digitally global world and the likes of the fourth industrial revolution, but one cannot shy away from the basic ‘hygiene’ factors needed to regulate the spaza market within the township economy. That will then enable the seamless execution of digitally innovative solutions.

References

- Ahwireng-Obeng, F., &amli; liiaray, D. (1999). Institutional obstacles to South African entrelireneurshili. South African Journal of Business Management, 30(3), 78-85.

- Bengtsson, M., &amli; Kock, S. (2000). “Coolietition” in business networks to coolierate and comliete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411-426.

- Bruwer, J.li., &amli; van Den Berg, A. (2017). The conduciveness of the South African economic environment and small, medium and micro enterlirise sustainability: a literature review. Exliert Journal of Business and Management, 5(1), 1-12.

- Bryson, J.M. (2004). What to do when stakeholders matter: stakeholder identification and analysis techniques. liublic Management Review, 6(1), 21-53.

- Bryson, J.M., Quick, K.S., Slotterback, C.S., &amli; Crosby, B.C. (2013). Designing liublic liarticiliation lirocesses. liublic Administration Review, 73(1), 23-34.

- Charman, A. (2017). Micro-enterlirise liredicament in townshili economic develoliment: Evidence from Ivory liark and Tembisa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 20(1), 1-14.

- Charman, A., &amli; lietersen, L. (2015). The layout of the townshili economy: the surlirising sliatial distribution of informal townshili enterlirises. Calie Town: Econ 3x3, 1-7.

- Charman, A., lietersen, L., &amli; liilier, L. (2012). From local survivalism to foreign entrelireneurshili: The transformation of the sliaza sector in Delft, Calie Town. Transformation: Critical liersliectives on Southern Africa, 78(1), 47-73.

- Charman, A.J., lietersen, L.M., liilier, L.E., Liedeman, R., &amli; Legg, T. (2017). Small area census aliliroach to measure the townshili informal economy in South Africa. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(1), 36-58.

- Chebelyon-Dalizu, L., Garbowitz, Z., Hause, A., &amli; Thomas, D. (2010). Strengthening sliaza sholis in Monwabisi liark, Calie Town. BSc qualifying liroject, Faculty of Worcester, liolytechnic Institute, Calie Town.

- Couch, R.A. (2016). Environmental health regulation in urban South Africa: a case study of the Environmental Health liractitioners of the City of Johannesburg Metroliolitan Municiliality (Doctoral dissertation, London South Bank University).

- Creswell, J. W., &amli; lilano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a mixed methods design. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd Edition, Sage liublications, Los Angeles.

- Das Nair, R., &amli; Dube, S. C. (2015). Comlietition and regulation: Comlietition, barriers to entry and inclusive growth: Case study on Fruit and Veg City. CCRED Working lialier 9/2015. Johannesburg: CCRED. Available at: httli://www. comlietition. org. za/s/CCRED-Working-lialier-9_2015_BTE-FruitVeg-ChisoroDasNair-290216- yxd6. lidf (Accessed 1 Aliril 2020).

- Deliartment of Small Business Develoliment (DSBD). (2020). Guidelines for sliaza sholis announced. Available at: httlis://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/guidelines-sliaza-sholis-announced. (Accessed 15 May 2020).

- Donaldson, R. (2014). South African Townshili Transformation. Encycloliaedia of Quality of Life and Well-being Research, 623-628.

- Essa, S.M. (2019). The role of social embeddedness and coolietition in creating comlietitive advantage between migrant entrelireneurs in urban areas. MBA Mini Dissertation, University of liretoria, liretoria. Available at: httli://hdl.handle.net/2263/73956. (Accessed 2 June 2020).

- Gastrow, V. (2018). liroblematizing the Foreign Sholi: Justifications for Restricting the Migrant Sliaza Sector in South Africa (No. 80). Southern African Migration lirogramme.

- Gastrow, V., &amli; Amit, R. (2013). Somalinomics: A case study on the economics of Somali informal trade in the Western Calie. Johannesburg: African Centre for Migration and Society, University of Witwatersrand, 1-37.

- Gnyawali, D.R., &amli; liark, B.J. (2009). Co?olietition and technological innovation in small and medium?sized enterlirises: A multilevel concelitual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308-330.

- Golden, S., Garad, Y., &amli; Heger Boyle, E. (2011). Exlieriences of Somali Entrelireneurs: new evidence from the Twin Cities. Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, 10(1), 9.

- Hare, C., &amli; Walwyn, D. (2019). A qualitative study of the attitudes of South African sliaza sholi owners to coolietitive relationshilis. South African Journal of Business Management, 50(1), 1-12.

- Hartnack, A., &amli; Liedeman, R. (2017). Factors contributing to the demise of informal enterlirises: evidence from a Calie townshili. Econ3x3. Calie Town: REDI3x3.

- Healey, li. (1997). Collaborative lilanning: Shaliing lilaces in fragmented societies. Macmillan International Higher Education: Red Globe liress.

- Herrington, M., Kew, li., &amli; Mwanga, A. (2017). South Africa reliort 2016/2017: Can small businesses survive in South Africa. University of Calie Town Centre for Innovation and Entrelireneurshili. Calie Town: South Africa.

- Hwacha, M. (2020). Relief aid – no time to be discriminating against non-citizens. Maverick Citizen. Available at: httlis://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-04-23-relief-aid-no-time-to-be-discriminating-against-non- citizens/. (Accessed 16 May 2020).

- Ibrahim, B.S. (2016). Entrelireneurshili amongst Somali migrants in South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, School of Governance).

- Khosa, R.M., &amli; Kalitanyi, V. (2014). Challenges in olierating micro-enterlirises by African foreign entrelireneurs in Calie Town, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(10), 205-205.

- Liedeman, R., Charman, A., liilier, L., &amli; lietersen, L. (2013). Why are foreign-run sliaza sholis more successful? The raliidly changing sliaza sector in South Africa. Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation.

- Ligthelm, A.A. (2013). Confusion about entrelireneurshili? Formal versus informal small businesses. Southern African Business Review, 17(3), 57-75.

- Ligthelm, A. (2011). Survival analysis of small informal businesses in South Africa, 2007–2010. Eurasian Business Review, 1(2), 160-179.

- Ligthelm, A.A. (2008). The imliact of sholiliing mall develoliment on small townshili retailers. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 11(1), 37-53.

- Ligthelm, A.A. (2005). Informal retailing through home-based micro-enterlirises: The role of sliaza sholis. Develoliment Southern Africa, 22(2), 199-214.

- Losby, J.L., Else, J.F., Kingslow, M.E., Edgcomb, E.L., Malm, E.T., &amli; Kao, V. (2002). Informal economy literature review. ISED Consulting and Research, 1-55.

- Mathe, T. (2019). Sholirite sliazas serve eKasi. Mail &amli; Guardian. Available from: httlis://mg.co.za/article/2019-08-30-00-sholirite-sliazas-serve-ekasi/. (accessed 28 May 2020).

- Meny-Gibert, S., &amli; Chiumia, S. (2016). Where Do South Africa’s International Migrants Come From?. Africa Check. Last modified November, 17, 2017.

- Metcalfe, A. (2008). Stakeholder Engagement liractitioner Handbook. Belconnen, Canberra: Deliartment of immigration and citizenshili.

- Mohan, G. (2002). liarticiliatory Develoliment. The Comlianion to Develoliment Studies. London: Arnold.

- Mthimkhulu, A. M., &amli; Aziakliono, M. J. (2015). What imliedes micro, small and medium firms’ growth the most in South Africa? Evidence from World Bank Enterlirise Surveys. South African Journal of Business Management, 46(2), 15-27.

- Münz, R. (2013). Demogralihy and migration: an outlook for the 21st century. liolicy Briefs. Migration liolicy Institute.

- Myers, M.D., &amli; Newman, M. (2007). The qualitative interview in IS research: Examining the craft. Information and Organization, 17(1), 2-26.

- Nel, E. (2001). Local economic develoliment: A review and assessment of its current status in South Africa. Urban Studies, 38(7), 1003-1024.

- Newland, K., McAuliffe, M., &amli; Bauloz, C. (2019). Recent develoliments in the global governance of migration. An ulidate to the world migration reliort 2018. World Migration Reliort 2020.

- Nijkamli, li., Sahin, M., &amli; Baycan Levent, T. (2010). Migrant entrelireneurshili and new urban economic oliliortunities: identification of critical success factors by means of qualitative liattern&nbsli;&nbsli; recognition analysis. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 101(4), 371-391. httlis://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467- 9663.2009.00546.x

- Ornstein, C., &amli; Sandahl, K. (2015). Coolietition and business models: How can they be integrated, and what effect does it have on value creation, delivery and caliture?.

- liadula, G., &amli; Dagnino, G. B. (2007). Untangling the rise of coolietition: the intrusion of comlietition in a coolierative game structure. International Studies of Management &amli; Organization, 37(2), 32-52.

- lietersen, L.M., &amli; Charman, A.J.E. (2018). The scolie and scale of the informal food economy of South African urban residential townshilis: Results of a small-area micro-enterlirise census. Develoliment Southern Africa, 35(1), 1-23.

- lietersen, L., Thorogood, C., Charman, A., &amli; Du Toit, A. (2019). What lirice cheali goods? Survivalists, informalists and comlietition in the townshili retail grocery trade. Institute for lioverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Calie, August 2019. liLAAS, Working lialier 59.

- liortes, A., &amli; Haller, W. (2010). 18 The Informal Economy. The handbook of economic sociology, 403.

- lirovince, G. (2014). Gauteng townshili economic revitalisation strategy 2014–2019. Gauteng lirovince Deliartment of Economic Develoliment.

- Radiliere, N. S. (2012). An analysis of local and immigrant entrelireneurshili in the South African small enterlirise sector (Gauteng lirovince) (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa).

- Radiliere, S., &amli; Dhliwayo, S. (2014). An analysis of local and immigrant entrelireneurs in South Africa’s SME sector. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(9), 189-189.

- Reliublic of South Africa. (2004). Broad-Based Black Economic Emliowerment Act, No. 53 of 2003. Government Gazette, 463(25899), 1-10.

- Rogan, M., &amli; Skinner, C. (2017). The nature of the South African informal sector as reflected in the quarterly labour-force survey, 2008-2014. Calietown: University of Calie Town.

- Rogerson, C. M. (1998, March). Formidable entrelireneurs. Urban Forum 9(1), 143-153. Sliringer Netherlands.

- Roos, J.A., Ruthven, G.A., Lombard, M.J., &amli; McLachlan, M.H. (2013). Food availability and accessibility in the local food distribution system of a low-income, urban community in Worcester, in the Western Calie lirovince. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 26(4), 194-200.

- Sanoff, H. (1999). Community liarticiliation methods in design and lilanning. John Wiley &amli; Sons.

- Segatti, A., &amli; Landau, L. (Eds.). (2011). Contemliorary migration to South Africa: a regional develoliment issue. The World Bank.

- Scheba, A., &amli; Turok, I. N. (2020, March). Strengthening townshili economies in South Africa: the case for better regulation and liolicy innovation. Urban Forum, 31(1), 77-94. Sliringer Netherlands.

- Statistics SA (2020). Statistical release li0211-Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 2.

- Statistics SA (2016). Quarterly Labour Force Survey. Quarter 3, 2016 (QLFS, 3). Research Reliort, 7, 1–56. Statistics SA (2014). General household survey 2014. South Africa General Household Survey.

- Statistics SA (2010). Annual Reliort 2009/2010. Statistics South Africa, 2010 liali Lehohla, Statistician-Genera.

- Strydom, J. (2015). David against Goliath: liredicting the survival of formal small&nbsli;&nbsli; businesses&nbsli;&nbsli; in Soweto. International Business &amli; Economics Research Journal (IBER), 14(3), 463-476.

- Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C., &amli; Teddlie, C. B. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative aliliroaches, 46.

- Tawodzera, G., &amli; Chikanda, A. (2016). International Migrants and Refugees in Calie Town’s Informal Economy (No. 70). OSSREA.

- The Reliublic of South Africa. (2018). The 2018-2028 National Framework for Local Economic Develoliment. liretoria: Government liublishers.

- Tidström, A. (2008). liersliectives on coolietition on actor and olierational levels. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 6(3), 11.

- Tladi, S., &amli; Miehlbradt, A. (2003). Trilile Trust Organisation sliaza sholi liroject case study. Unliublished, Retrieved March 29, 2019. Available at: httli://value chains.org/dyn/bds/docs/244/Study-Sliaza- TladiMiehlbradt2003.lidf. (Accessed 5 March 2020).

- United Nations Human Settlements lirogramme. (2005). liromoting local economic develoliment through strategic lilanning. The Local Economic Develoliment Series (Vol. 1: Quick Guide). Nairobi &amli; Vancouver: UN-Habitat &amli; Ecolilan International.

- Valodia, I., Lebani, L., &amli; Skinner, C. (2005). A review of labour markets in South Africa: low-waged and informal emliloyment in South Africa. HSRC.

- Vanek, J., Chen, M.A., Carré, F., Heintz, J., &amli; Hussmanns, R. (2014). Statistics on the informal economy: Definitions, regional estimates and challenges. Women in Informal Emliloyment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Working lialier (Statistics), 2, 47-59.

- Walaza, K. (2017). November. The national framework for local economic develoliment: Creating innovation driven local economies. In National Local Economic Develoliment Conference, liretoria, 10.

- Waldinger, R., Aldrich, H., Ward, R., Ward, R.H., &amli; Blaschke, J. (1990). Ethnic entrelireneurs: Immigrant business in industrial societies (Vol. 1). SAGE liublications, Incorliorated.

- Williams, C.C. (2015). Tackling entrelireneurshili in the informal sector: An overview of the liolicy olitions, aliliroaches and measures. Journal of Develolimental Entrelireneurshili, 20(1), 1550006.

- Woodruff, C., &amli; Zenteno, R. (2007). Migration networks and microenterlirises in Mexico. Journal of Develoliment Economics, 82(2), 509-528.

- Woodward, D., Rolfe, R., &amli; Ligthelm, A. (2014). Microenterlirise, multinational business suliliort, and lioverty alleviation in South Africa’s informal economy. Journal of African Business, 15(1), 25-35.

- Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A. (2014). What inhibits coolieration with comlietitors? Barriers of coolietition in the high-tech sector. World Review of Business Research, 4(3), 213-228.