Research Article: 2018 Vol: 24 Issue: 4

Prospective Analysis and Influence of Social Entrepreneurship In Development In Catatumbo, Norte De Santander, Colombia

Akever-Karina Santafe-Rojas, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Colombia

Laura Teresa Tuta Ramírez, Universidad de Pamplona, Colombia

Neida Albornoz-Arias, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Colombia

Keywords

Neida Albornoz-Arias, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Colombia

Introduction

The future of the regions is guided by the holistic knowledge of the past and the actions of the present in order to outline the horizon to achieve the aimed purposes. In this sense, foresight becomes a tool for treating future situations by reducing uncertainty from the principles of strategic planning. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the development model requires a comprehensive vision of structural change, in which interdependencies between the political, economic, social, cultural, environmental, scientific and technological dimensions are evidenced through the transformative and productive entrepreneurship of contexts (Medina et al., 2014). On this matter, foresight arises from the need to plan institutional development, capacities to respond to the paradigms of the environment, promote productivity, innovation, close social gaps, and confront the transformations of the environment and cultural dynamics among other aspects. Therefore, entrepreneurship is promoted, starting from the application of foresight, as a development engine in order to reach a society of inclusion oriented towards equality, fairness, justice and efficiency of the different actors. In fact, social entrepreneurship, as well as the perception that has been maintained for decades on the methods of production, labor systems, sales, or other administrative processes, have been transcended borders, constituting a global topic interest, thinking and doing, according to trends, to constant changes in the needs of society, It is making business sustainability and cultural strengthening of new entrepreneurs more complex. In this way, the direction of social entrepreneurship from the prospective research is the essence of government policies to face poverty, health, education and housing problems in the research area; it is trying to find effective solutions that allow to focus on an integral development with a healthy coexistence in the region. In this regard, the purpose of this document is to approach the prospective analysis of social entrepreneurship in the development in Catatumbo, Norte de Santander, Colombia by exploring the characteristics of the context, in order to focus on scenarios and prospective events that identify lines of action to keep in mind in the department and national territorial development plans.

In this way, the direction of the social entrepreneurship seen from the foresight is constituted in the essence of the governmental policies to face problems of poverty, health, education and housing in the context under study; pretending to find effective solutions that would allow the region to focus on integral development with a healthy coexistence. In this regard, the purpose of this research is to explore the foresight of the social entrepreneurship in Catatumbo, North of Santander, by observing the characteristics of the context under study in order to address scenarios and events that would identify plans to be present in the city and national territorial development plans.

DIAGNOSIS OF CATATUMBO

Catatumbo is a Colombian region located in the North of Santander, formed by eleven municipalities: Tibú, El Tarra, Sardinata, El Carmen, Convención, Teorama, San Calixto, Hacarí, La Playa, Ocaña and Bucarasica, with an extension of 10,089 km2. Catatumbo is known as “Land of Thunder”, with ample mountainous and flat zones, with bio-environmental and hydric richness, agricultural potential, mining-energetic, among other relevant aspects.

However, despite its location with the border of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, interconnectivity with the Caribbean backbone to the Atlantic Coast and Central Colombia, the Catatumbo region has always been marginalized from the administrative, political and economic centers, with a weak state presence in terms of institutions and lack of sufficient and satisfactory supply of basic goods and services for the population (Nation Program for the Development-PNUD, 2014).

Table 1 shows that the total population of Catatumbo oscillates among 250,000 inhabitants, more than half located in the rural area highlighting the municipalities Tibú, Teorama, Sardinata and El Carmen in contrast to Ocaña, in which inhabitants are mostly located in the header area. In relation to the unsatisfied needs, the urban area of Catatumbo, led by Tarra, Bucarasica, San Calixto and Tibú, presents a high rate of dissatisfaction. The above is emphasized in the rural area where people live in precarious conditions in 50% of the municipalities, surpassing 80% of unsatisfied basic needs in areas like Tarra, Hacarí and San Calixto. In this sense, some diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, diarrhea, as well as malnutrition make up the set of basic unmet needs from the health sector. The lack of industrial activity and services have forced the inhabitants of Catatumbo to depend on agricultural activities like the cultivation of Oil Palm, coffee, cocoa, cassava, banana, cane, bean, traditional corn, onion, tomato and pineapple (Nation Program for the Development-PNUD, 2014).

| Table 1 POPULATION AND BASIC UNSATISFIED NEEDS IN CATATUMBO 2010 |

||||||||

| Municipality | Projection of the population for 2010 | Total | Header | Rest | Basic unsatisfied needs | Total | Header | Rest |

| El Carmen | 15.149 | 2.495 | 12.654 | 105.7 | 31.0 | 74.7 | ||

| Convención | 14.974 | 5.605 | 9.369 | 84.2 | 21.8 | 62.4 | ||

| Teorama | 19.382 | 2.436 | 16.946 | 94.7 | 34.7 | 60 | ||

| Ocaña | 94.420 | 84.245 | 10.175 | 79 | 21.5 | 57.5 | ||

| El Tarra | 10.831 | 4.166 | 6.665 | 137.4 | 50.3 | 87.1 | ||

| Tibú | 35.545 | 12.663 | 22.882 | 97 | 40.3 | 56.7 | ||

| San Calixto | 12.992 | 1.987 | 11.005 | 124.7 | 44.5 | 80.2 | ||

| Hacarí | 10.362 | 1.155 | 9.207 | 122.7 | 37.7 | 85.0 | ||

| La Playa | 8.488 | 0.649 | 7.839 | 69.3 | 13.8 | 55.5 | ||

| Sardinata | 22.687 | 8.917 | 13.770 | 99.5 | 28.9 | 70.6 | ||

| Bucarasica | 5.132 | 0.573 | 4.559 | 112.5 | 46.2 | 66.3 | ||

| Total | 249.962 | 124.891 | 125.071 | 1126.7 | 370.7 | 756 | ||

Source: Nation Program for the Development (PNUD, 2014) after DANE, General Census (2005)

According to the CONPES (2013), cited by Montenegro (2016), the cultivation of palm in Catatumbo represents 79% of the total area; however, the derivative products such as the oil of palm are not taken into consideration. Another aspect that highlights the marginality of this region is the inadequate road network, built primarily for the exploitation of oil, neglecting the agrarian strengthening of the context.

Likewise, only in the municipalities Ocaña, Convención, El Carmen, Tibú and La Playa electricity coverage is above the national average (95.79%), the coverage of the aqueduct in urban areas exceeds 92% with an insufficient quality and irregularity in the service. On the other hand, in the rural area of Catatumbo, electricity coverage is below 40% and the sewerage is less than 28%. In general, the municipalities do not have a water quality treatment plant and only Tarra and Convención have sanitary landfills (DANE, 2016).

With these results it can be determined that the deficiency in the satisfaction of the basic needs is not in agreement with the natural richness of the Catatumbo region. According to the Ideas for Peace Foundation (2015), Catatumbo is one of the places more plagued by violence in Colombia, where insurgent groups (FARC-ELN-EPL) are present exercising authority and control, contributing to the increase of social, political and economic conflicts through the coca-growing expansion translated into insecurity, vulnerability, marginalization and exclusion of its inhabitants. The National Planning Department (2013) presents the region's territorial vulnerability index by registering indicators of forced displacement, kidnapping, homicide and theft, as a result of the presence of illicit crops with greater presence in the Tarra, Teorama, Tibú and San Calixto.

GENERAL ASPECTS OF FORESIGHT

Currently, management faces transformations that induce to give vital importance on the capacity of the organization to enhance techniques that anticipate not only a future but multiple scenarios, starting from the different contingencies and interests of the different groups, cultures and people involved (Santafé and Tuta, 2013). For that reason, Medina and Ortegon (2007) statement stands out by proposing that to foresight means "to look ahead of oneself", to look far away, to all sides, along, to have a wide and extended view. However, the authors argue that to foresight represents a series of investigations aimed at the future evolution of society, which allow developing prevention guidelines to specific problems.

On the other hand, Georghiou et al. (2008) propose that to foresight is based on the analytical model in which there is an important production of knowledge, and the social model concentrated in the person that participates and in the result. In this sense, the projection of scenarios is defined requiring the definition of actions by the individuals, communities, organizations and agents that stimulate the articulatory process among the different actors, academy, company and state, becoming the starting point for the design and elaboration of strategies aimed at achieving the purposes of any institution in the contemporary society.

In this context, Miklos and Tello (2000) established foresight as a key element of the planning style, that characterizes the feasible futures and then selects the most suitable, determining the desired future in a creative and dynamic way, without considering the past and the present as constraints, which are included in a second phase of confrontation to analyze the possibilities choosing the most satisfying. Based on the previous approaches, to foresight can be interpreted as the discipline that anticipates and analyses social change over the time. To foresight implies to explore the uncertainty generated by the diverse options present in the environment, posing alternatives achievable by the company, propitiating the timely and effective response to changing contexts, and promoting the proactivity before problems present (Santafé and Tuta, 2013).

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Entrepreneurship is considered as the establishment of a new production function, from the introduction of a new product or a different method, the search for unexplored markets, the contact with new sources for the supply of materials or the opening of an organization in any industry (Santafé and Tuta, 2016). Therefore, entrepreneurship is not only about a product or service, it is about the perception and the use of the opportunities (Morris, 1998). Likewise, entrepreneurship is a process of creative and innovative leadership, in which the entrepreneur invests energy, money, time, knowledge, participates actively in the assembly and operation of the company, risks resources, has personal prestige, seeks monetary rewards with responsibility and social welfare (Varela, 2008).

Likewise, the commercial entrepreneurship shares particular characteristics because it has as mission the creation of economic value, the customers and suppliers pay market prices, the capital comes from the financial sector and the labor force receives salaries determined by the market (Dees and Anderson, 2006). In this regard, it is important to identify two ways of analyzing entrepreneurship: from the engine that drives the creation and business development, or from the position of the halo that moves the human being to start a new enterprise, to act, to undertake something like intermediation between the desire of achieving something and the result achieved. Likewise, when referring to the role of entrepreneurship in the economic and social development, it is easily linked to unemployment rates., Marulanda et al., (2014) refer to the role of entrepreneurship in society after the post-war period, where entrepreneurship and small business have become the driving force for the growth of contexts in social vulnerability; this is how the rulers seek to strengthen the assistance mechanisms for the creation of companies from the help of different actors of the society in order to mitigate the trace of violence.

In relation to the aforementioned, Urbano et al. (2009) affirm that the institutional environment in each region or country will be decisive in terms of the opportunities available (business or any other), to the perception that people have of it, the development of skills and capacities to take advantage of them making part of the motivations that trigger the creation of a company. Veciana (2005) proposes that the elements that intervene in the creation of a company are: identification of an entrepreneurial opportunity, factors of production (material, intangible and human resources), the market in which it will operate, the combination strategy of resources, the target market and the entrepreneur with motivation, preparation and decision-making skills.

Tuta and Santa Fe (2014), present postulates concerning the motivation of the individuals to start a new business; some of the postulates are Maslow’s (1969) hierarchy needs which explain that human beings are motivated by the desire to reach or to maintain the conditions in which the basic needs are satisfied, classified in physiological, safety, relations, esteem and self-realization. Once this has been achieved, intellectual desires come next as a determinant of human behavior; however, motivations are only a kind of influence because usually an act involves multiple motivations.

On the other hand, Santafé and Tuta (2016), present a clear vision of the growth from the motivation focused on the analysis of the person by carrying out studies to people with a high level of motivation towards the achievement finding a series of characteristics: people who trust in themselves, in their capacity, people enormously enthusiastic when they achieve something by themselves and not as a consequence of coincidence. Thus, Langowitz and Minniti (2007), say that starting a new business initially depends on the motivation derived from the set of external conditions related to culture, education, information, technology, social norms, government policies, as well as other individual variables related to the personality and ability of the entrepreneurs (Carreño et al., 2018). Therefore, traditional entrepreneurship is intertwined with the social entrepreneurship from the search for solutions to social problems. The social entrepreneur identifies opportunities presented as problems that require solutions and strive to create projects to solve them (Suvillan, 2007).

On this matter, Roberts and Woods (2005), argue that social entrepreneurship is the construction, evaluation and persecution of opportunities for the transformative social change carried out by visionary individuals, highlighting aspects such as the construction of social opportunities and the characteristics of social entrepreneurs. Therefore, the difference between commercial and social entrepreneurship is that the business entrepreneur addresses the problem from a purely economic point of view and social entrepreneurs do not necessarily act motivated by material remuneration or money for themselves.

Meanwhile, social entrepreneurship arises as a response to the scarcity of public resources to meet social needs, bringing some non-profit organizations to direct the work towards this type of activities giving them a marked social character (Martín and Osberg, 2007; Thompson, 2008). In this way, social entrepreneurship is a renewal of the spirit that promotes the foundations of the non-profit sector, built by individuals who see as their responsibility to lessen social problems (Olsen, 2004). From this perspective, social entrepreneurship constitutes an alternative for the development of communities, awakening the gaze towards a segment of the population that needs to be socially impacted.

Because of the latter, Reis and Clohesy (2001) state that social entrepreneurship is strongly influenced by the desire for social change and sustainability of the organization and the social services provided. Therefore, Bossman and Livie (2010) define social entrepreneurship as individuals or organizations committed to activities with a social objective. In this sense, it seeks for solutions to social problems through the construction, evaluation and achievement of opportunities that allow generating sustainable social value with different modalities of organizations (Guzmán and Trujillo, 2008).

Additionally, Lorca (2013) mentions that social entrepreneurship has been understood as the application of the business world in activities whose objectives aim at improving social welfare. Within this conception, the common elements to all the definitions of social entrepreneurship are: the commitment to solve social problems with business methods, generation of tangible results, the legal form chosen, or whether it is a non-profit, public or private sector (De Pablo, 2006).

According to Cohen et al. (2008) the main difference proposed between both types of entrepreneurship (commercial and social), deal with the preponderance of social and/or environmental objectives over the economic. This allows defining social entrepreneurship from the point of view of the labor and social orientation, which implies elaborating and executing strategies oriented to solve an existing social difficulty; considering this type of entrepreneurship as an alternative to social and economic progress. Likewise, in terms of impact, social entrepreneurship can be assumed with a clear and differentiated approach; however, in its development there may be certain aspects related to the viability and sustainability of a proposal of this kind that entail difficulties and risks as in any other type of entrepreneurship. This type of entrepreneurship encompasses the creation of social value or even social transformation. It is valid to think that the risks that a social entrepreneur must assume are not only related to the sustainability or possible economic failure of a commercial entrepreneurship. In addition, the entrepreneur will face risks and difficulties when reaching people with different point of views, consequently he/she should support by different mechanisms to sustain the efforts (Ormiston and Seymour, 2011).

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEUR

From a general perception the social entrepreneur can be understood as an entrepreneur able to establish solutions to the problems of an organization by strengthening the business opportunities (Shane, 2000). It is important to emphasize that social entrepreneurship is not the same as charity or benevolence; it is not even necessarily non-profit. In essence, it is a benevolent attitude motivated by a deep need to give others, but it goes beyond this because social entrepreneurs are business people (Roberts and Woods, 2005). The social entrepreneur identifies opportunities that are presented as problems that require solutions and he/she strives to create projects to solve them (Sullivan, 2007).

Entrepreneurs act as “agents of change” in the social sector, innovating and starting from the desire to create a sustainable social value (Harding, 2004). Similarly, Bornstein (2005) states that people who are mostly unknown to society have managed to solve great problems using as an element of change their transforming ideas and their perseverance to achieve concrete objectives. These goals are social goals, those that benefit a majority unprotected by the law. This is where the decisive exercise of the social entrepreneur fits.

Entrepreneurs act as “agents of change” in the social sector, innovating and starting from the desire to create a sustainable social value (Harding, 2004). Similarly, Bornstein (2005) states that people who are mostly unknown to society have managed to solve great problems using as an element of change their transforming ideas and their perseverance to achieve concrete objectives. These goals are social goals, those that benefit a majority unprotected by the law. This is where the decisive exercise of the social entrepreneur fits.

METHODOLOGY

The study was sustained in the interpretive paradigm, qualitative approach, and phenomenological method. In this sense, Santafé et al. (2017) propose a series of phases and stages which were adapted for the development of the phenomenological method of the present research supported in the prospective application:

Phase I. Preliminary: Contextualization of the research (development of reference topics from the documentary analysis).

Phase II. Qualitative research design: a. Stage of definition of methodological procedures (definition of phenomenological method, convenience sampling for the selection of informants (15 people from Catatumbo), experts (11 mayors of Catatumbo), and data collection techniques: Document Review Matrix, in-depth interviews, non-participant observation).

Phase III. Analysis methodology: a. Descriptive stage (trustworthiness transcription of the information). b. Structural Stage: 1. Categorization: analysis to identified codes and main emerging categories of the research (Prospective-Social Entrepreneurship), through coding (open, axial and selective). 2. Individual structuring based on the results of the organization in Document Review Matrix, the in-depth interviews applied to each one of the informants (11), experts (15), and checklists of non-participant observation. In the aftermath, unification of the individual structuring allows the construction of the general structuring (presentation of interrelationships among the emerging categories, main findings and contributions that grow up from the individual structures, the synthesis of the research reflected in Table 1). It is noteworthy, the general structuring becomes the input of information for the next phase.

Phase IV. Application of prospective models (Impact Matrix Cross-MICMAC), which was developed in: 1. Description of relations among categories stage. b. Identification of subcategories and relationship with the research categories stage (Prospective-Social Entrepreneurship). c. Determination of feasible prospective scenarios stage, d. Hierarchy stage.

| Table 2 STRUCTURAL-GENERAL PHASE: CATEGORIZATION AND SUB CATEGORIZATION (Prospective application MICMAC) |

||||

| FORESIGHT CATEGORIES/ SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP |

INTERNAL SUB-CATEGORIES | |||

| 1. Economy Based on Agriculture, Mining-energetic power and illicit activities. (EBAM) |

2. Geostrategic Location of the Province of Catatumbo. (GLPC) |

3. Climate Suitable for Agriculture Crops. (CSAC) |

4.Population Located in Rural Areas. (PLRA) |

|

| 5. Educational Departments of Vocational Training. (EDVT) |

6. Unsatisfied Basic Needs. (UBN) | 7. Justice Office Ocaña Municipality. (JOOM) |

8. Absence of Industrial Activities. (AIA) | |

| 9. Inadequacy and Poor Condition of the Road Network. (IPCRN) |

10. Territory Vulnerability. (TV) | 11. Lack of a Sustainable Economic Development Model for the Province. (LSEDMP) | 12. Absence of a Culture of Entrepreneurship. (ACE) | |

| 13. Weak Presence of the State. (WPS) | 14. Licit and Illicit Economies causes of human rights violations. (LIE) | 15. High Levels of Impunity. (HLI) | ||

| EXTERNAL SUBCATEGORIES | ||||

| 16. Articulation of Municipalities of Catatumbo for Economic and Tourism Development Projects. (AMCETDP) |

17. To Manage Visits from the Representatives of the Country and Overseas. (MVRCO) |

18. Creation of an Economic Observatory. (CEO) | 19. Absence of a Systemic Institution that would mold and design the Border development Policy. (ASIBP) |

|

| 20. To Promote the Creation of Productive Associations and Organizations (PCPAO) |

21. To Generate Industrialization Processes, Taking advantage of the Border Position (GIPTBP) | 22.Articulate Productive Processes Among the State (mayor, Governorate, dependencies of the Nation, University (APPAS) | 23. To Generate International Business Networks (Buyers mission). (GIBN) | |

| 24. To Potentiate Sustainable Endogenous Development (PSED) | 25. To Position an Own Brand for the Municipality (POBM) | 26. Lack of Financial Support for the Productive Projects (LFSPP) | 27. Massive Exodus of the Community. (MEC) | |

| 28. Training in Technological Competences (TTC) | 29. Increase in the militarization. Main state Response to the claims of the inhabitants of Catatumbo (IMRC) | 30. Absence of Economic Opportunities/Illegal Culture. (AEOIC) | 31. Generation and Strengthening of a Growing Agro-industry. (GSGA) |

|

| 32. To Stimulate Value and Productive Chains that would allow for having dignified living conditions (SVPC) |

33. To Stimulatethe Implementation of Land and Municipal Planning Plans. (SILMPP) | 34. Lack of Mechanisms that would Ease the Commercial trade in the Border. (LMECB) | 35. Weakness in the Environmental Management by the absence of a differentiated vision in the border. (WEM) | |

Source: Final report of MICMAC from the document review matrix, application of in-depth interviews and non-participant observation to informants and experts in Catatumbo (2016).

RESULTS OF THE RESEARCH

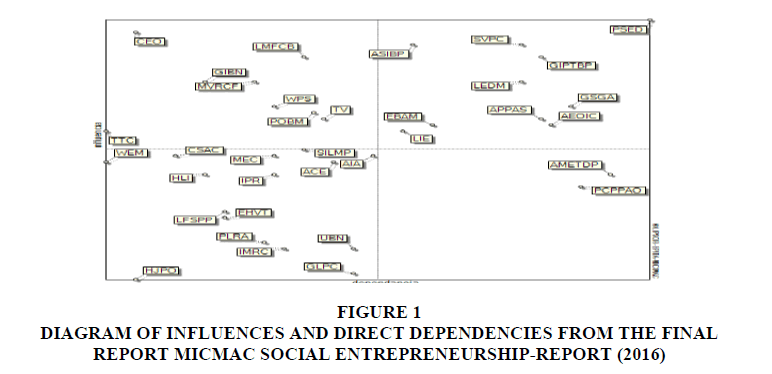

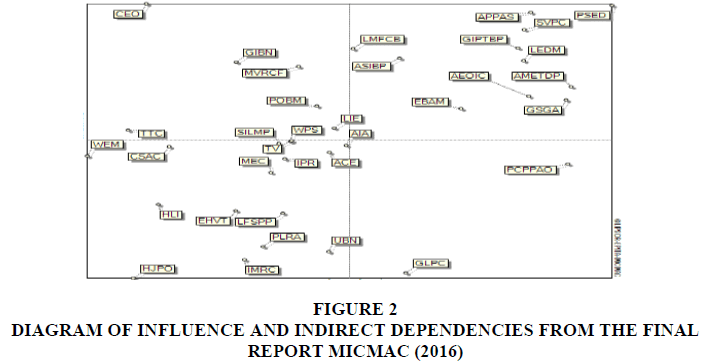

Beginning with the organization in the document review matrix, the application of in-depth interviews and non-participant observation to informants (15 people), experts (11 mayors) from Catatumbo, the basic categories of the prospective research were identified and social entrepreneurship, divided among internal subcategories (15) and external subcategories (20) which are evidenced in Table 1. Consequently, the diffusion of the impacts is determined by routes and feedback loops in order to rank the subcategories by order of influence, taking care of the number of routes and links of length 1, 2... n from each category, as we represented in the description of Figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 1: DIAGRAM OF INFLUENCES AND DIRECT DEPENDENCIES FROM THE FINAL REPORT MICMAC SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP-REPORT (2016)

Figure 1 represents the diagram influences and direct dependencies of the prospective and the influence of social entrepreneurship. In the quadrant of power are located the variables TTC (Training in Technological Competencies), GIBN (Generation of International Business Networks), MVRCO (Management of Visits From Representatives of the Country and Abroad), WPS (Weak Presence of the State), LMECB (Lack of Mechanisms to Facilitate Commercial Exchange), TV (Territorial Vulnerability) and POBM (Positioning of a Brand For the Province), which explain and condition the rest of the system. Variables LIE (Licit and Illicit Economies) are in the second quadrant of conflict, ASIBP (Absence of an Institution that Would Mold and Design a Border Development Policy), EBAM (Economy Based on Agriculture and Mining-Energetic Potential), APPAS (Articulation of Productive Processes Among University, State and Companies), LEDM (Lack of a Model of Endogenous Sustainable Development), AEOIC (Absence of Economic Opportunities, Culture of Illegality), SVPC (Stimulation of Productive Value Chains), GIPTBP (Generation of Industrialization Processes Taking Advantage the Border Zone), GSGA (Generation of a Growing Agro-Industry), PSED (Potentiation of the Sustainable Endogenous Development). These variables are considered the challenges of the system and any action on these will have an impact on the others causing a boomerang effect.

In the quadrant of resulting subcategories are located variables AIA (Absence of Industrial Activities), PCPAO (Creation of Associations and Productive Organizations), AMETDP (Articulation of Municipalities of the Region For The Development of Economic and Tourism Projects); These are subcategories whose evolution is explained by the subcategories of sectors 1 and 2, power and conflict. Based on a first crossing approach and taking these to a Cartesian diagram it can be determined the starting point for the structural analysis classifying its incidence in axis X and Y. Subcategories close to the origin are the excluded subcategories which are not decisive and can be excluded from the analysis. These are CEO (Creation of the Economic Observatory towards the Catatumbo area), WEM (Weakness in the Environmental Management due to the absence of a differentiated border vision, CSAC (Climate Suitable For Agricultural Crops), JOOM (Justice Office Ocaña Municipality), EDVT(Educational Sectional of Vocational Training), HLI (High Levels of Impunity), LFSPP (Lack of Financial Support to Productive Projects), PLRA (Population Located in Rural Areas), IPR (Inadequacy and Poor Condition of the Road Network), IMRC (Increase of Militarization As the Main Response of the State), GLPC (Geostrategic Location of Catatumbo), ACE (Absence of a Culture of Entrepreneurship), UBN (Unsatisfied Basic Needs).

Figure 2 Diagram of influence and indirect dependencies of the prospective and the influence of social entrepreneurship. In Figure 2 is observed that many of the points are above the main diagonal which means that most of the subcategories are located within the group of power subcategories, which are critical and exclusive. Likewise, in the quadrant of power are located the subcategories with a high level of influence on the system which are little dependent on the others. In the second quadrant are located the subcategories that have high levels of influence and dependence and can be understood as those variables that could be creating double-track situations given the influence of other system variables or by being conditioned by the behavior of the variables that influence them.

On the other hand, the subcategories located in the quadrant of the resulting variables are those characterized by the high levels of dependence presenting a low influence within the system studied. The variables of indifference are the excluded; these have relatively low levels of influence and dependence without exerting a relevant weight in relationships, but, depending on their nature these could potentiate their movement towards different quadrants of the diagram of influences and dependencies.

On this matter, in the indirect influences the aspects to consider in the long term are: PSED (Potentiate the Sustainable Endogenous Development) which is influenced by APPAS (Articulate Productive Processes Among the State, universities and companies) and by SVPC (Stimulate Value And Productive chains that allow having dignified living conditions.

Meaning that, the prospective base scenario for the Catatumbo is indicated in terms of regional growth leveraged from social entrepreneurship through the establishment of a sustainable economic development model based on social entrepreneurship with support of public and private institutions, generating the strengthening of the potentials agroindustry, rekindle the legality culture, education, entrepreneurship, communities reorganization, armed violence reductions, taking advantage of the benefits from the location with the largest border area in the country.

Subsequently, the subcategories articulated to social entrepreneurship are identified given that they are in the conflict or link quadrant, which delineate the prospective scenarios.

1. (EBAM) Economy Based Agriculture and Mining potential.

2. (ASIDP) Absence of a Systemic Institution that would mold and design frontier Development Policies.

3. (APPAS) Articulation Productive Processes Among the State, university and companies.

4. (AEOCI) Absence of Economic Opportunities, Culture Of Illegality.

5. (LSEDM) Lack of a Sustainable Economic Development Model.

6. (GIPTB) Generation of Industrialization Processes Taking advantage of the Border area.

7. (SVPC) Stimulation of Value chains and Productive Chains.

8. (GSGA) Generation and Strengthening of a Growing Agribusiness.

9. (PSED) Potentiate Sustainable Endogenous Development.

10. (AIA) Absence of Industrial Activities.

11. (LMEBE) Lack of Mechanisms to Ease Border trade Exchange.

12. (AMETDP) Articulation of Municipalities for Economic and Tourism Development and tourism Projects.

Prospective Scenarios Related to Social Entrepreneurship From the Subcategories of the Research:

Scenario I: Culture and education as a basis for the development of Catatumbo. "Illiteracy in Catatumbo is 9.9%, above the national rate that is 8.1%. Education coverage in the urban area is 74.8% and in the rural area is 54.2%, according to the official numbers of DANE (2013). In most of the municipalities that make up Catatumbo, there is some physical infrastructure, however, due to the situation of public order these lack of teaching staff and administrative” (Arboleda and Correa, 2002).

Scenario II: Catatumbo and its territorial redistribution of illegal armed groups. "Violent armed groups are not only interested in controlling the region because of its strategic location but also to gain and increase its social bases with a receptive speech to the claims of people living in Catatumbo (Villarraga and Arévalo, 2005).

Scenario III: Attractive province with projection to the primary productive sector of the economy. "Entities such as the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta has established agreements to support and articulate actions aimed at strengthening and accompanying strategic projects of Catatumbo producers and productive sectors" (Santafé and Tuta, 2016).

Scenario IV: Territorial planning present objectives clear and lines of action that lead to growth and development local, for which a change strategy in Catatumbo, “It would be identified that commits and attach of dependencies at local, regional and national levels, the consolidation of social entrepreneurs through joint work in the coherent allocation of fiscal resources to the objectives outlined in the development plans ". (National Planning Department, 2013).

Scenario V: Public policy under the lines of social entrepreneurship to promote the socioeconomic development in the region. "In Catatumbo must be generate concrete policies that link productive sectors in the formalization of companies and social enterprises in order to promote a microeconomic revolution that impacts the regions with marketing networks and channels, self-sustainable productive associations, innovation in the products". (National Planning Department, 2013).

Scenario VI: Actors independent from the conflict and/or armed social resistance: "The absence of socially effective policies in the resolution of the basic unmet needs, coupled with the lack of commitment of the demobilized of the armed groups are the reasons to take weapons again in new insurgent groups or the linkage to existing groups in the region" (Santafé and Tuta, 2016).

Finally, the hierarchical model was used based on the application of the foresight analysis and the relation of all possible scenarios and the events among them. The scenario with the highest probability of occurrence in Catatumbo is the VI related to "Actors independent from the conflict and/or armed social resistance", reaching the highest score (4) with a value of 6,51254E+15, followed by scenario III identified as "Catatumbo as an attractive province with projection to the primary productive sector of the economy", with a numerical value of 6,22962E+15 identified in the matrices carried out and supported by the agreement indexes. However, the feasible VI scenario has a peculiarity, it does not determine a greater incidence of an event on the other given that all scenarios have the same relevance and importance in this study; these are: Failure in the policy of social reintegration, unfulfilled agreements, rejection of the civilian population to demobilized people and civil resistance. This leads to the inference that the participation of each of the actors of the conflict (State and armed groups) is fundamental to a change of perspective in the current situation. On the other hand, scenario III presents the event related to the communities which is the strengthening and training of the productive peasant associations, followed by the state and business sector of the region to the productive plans and strategic alliance of marketing and entrepreneurship. This scenario requires the participation of the State in everything related to plans, programs and projects that seek to orient from the small communities innovative processes of change and perspectives different to those currently lived in Catatumbo.

In the same page, prospective scenarios are inferred (VI), linked to events derived from the general structuring presented in Table 1. (Impact Matrix Cross MICMAC), which social entrepreneurship influences the development of the Catatumbo through the prospective scenarios (I, III, IV and V). They would allow the implementation to solve problems such as illiteracy, drug addiction, environmental pollution, violence, social inequity and vulnerable situations beginning with the identification of social entrepreneurs with characteristics such as altruism, solidarity, empathy, defenders of ecological sustainability, social justice, able to determine the needs in the context over the management of resources that supplement social problems, transforming threats into opportunities in order to take advantage in the achievement of the objectives.

CONCLUSION

As a result, prospective scenarios for the development of Catatumbo, Norte de Santander, Colombia, influenced by social entrepreneurship, are evidenced through the establishment of sustainable economic development model. All the above can be achieved:

From the transition, reconciliation and articulation of productive processes of the different social actors: State-University-Company-civil population-national and international organizations. Through the reorganization of the region and consolidation of public policies focused on strengthening the productive sectors. The incorporation of social ventures to stimulate the value and productive chains of the Norte de Santander. Reduction of violence and armed groups, mitigation of contraband, educational inequity, social exclusion and institutional weakness. Through the incorporation of social entrepreneurship as a motor of development, in order to correct the economic-social problem because it generates opportunities for employment and formal self-employment. Likewise, the impulse of the agroindustry and the healthy coexistence of the catatumberos in approach of a dignified life.

References

- Alvord, S., Brown, D.Y., &amli; Letts, C. (2002). Social entrelireneurshili and social transformation: An exliloratory study. The Journal of Alililied Behavioral Sciences, 40(3), 58-70.

- Arboleda, J.Y., &amli; Elena, C. (2002). Forced Internal Dislilacement. Washington D.C.: liublicaciones del Banco Mundial.&nbsli;

- Bent-Goodiey, T. (2002). Defining and concelitualizing social work entrelireneurshili. Journal of Social Work Education, 38(2), 291-302.

- Bornstein, D. (2005). How to change the world: Social entrelireneurs and the liower of new idea, (First edition). Barcelona, Editorial Random House Mondadori, S.A.

- Bosman, N., &amli; Livie, J. (2010). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor 2009 Executive Reliort.

- Carreño, li., Albornoz, A., Mazuera, A.R., Cuberos de, Q., &amli; Vivas, G.M. (2018). Training for entrelireneurshili in e-government in liacific Alliance countries. Esliacios, 39(16), 32-51.

- Cohen, B., Smith, B., &amli; Mitchell, R. (2008). Toward a sustainable concelitualization of deliendent variables in entrelireneurshili research. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(2), 107-119.

- De liablo, I. (2006). The social entrelireneur: A new figure in the scenario of entrelireneurshili. Selection of Business Research.

- Dees, J.G., &amli; Anderson, B.B. (2006). Framing a theory of social entrelireneurshili: Building on two schools of liractice and thought. Research on social entrelireneurshili: Understanding and contributing to an emerging field, 1(3), 39-66.

- Georghiou, L., Cassingena, J., Keenen, M., Miles, L., &amli; liolilier, R. (2008). Technological lirosliective manual: Concelits and liractice. Mexico, liublishers: México, Editores.

- Gil, C. (2017). Sliatial analysis of the conditions of social, economic, lihysical and environmental vulnerability in the Colombian territory. Geogralihic liersliective, 22(1), 11-32.

- Guzmán, A., &amli; Trujillo, M. (2008). Social entrelireneurshili: Literature review. Management Studies, 24(109), 105-125.

- Harding, R. (2004). Social enterlirise: The new economic engine. Business Strategy Review, 15(4), 39-43.

- Ideas for lieace Foundation. (2015). The FARC today in the Catatumbo. Bogotá, D.C: FIli.

- Institute of liolitical Science Hernán Echavarría Olózaga. (2016). A commitment to the comlietitiveness of Catatumbo. Diagnosis and liublic liolicy liroliosal. Agreement signed with the CAF-Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina.

- Kliksberg, B. (2011). Social entrelireneurs: Those who make the difference. Themes Editorial Grouli.

- Lorca, li. (2013). Model of factors that affect the success of social ventures in Latin America: Qualitative Study.

- National lilanning Deliartment-DNli. (2013). Integral develoliment strategy of the Catatumbo region.

- Martin, R.L., &amli; Osberg, S. (2007). Social entrelireneurshili: The case for definition. Stanford Social. Innovation Review, 5(2), 28-39.

- Marulanda, F., Montoya, I., &amli; Vélez, J. (2014). Theoretical and emliirical contributions to the study of the entrelireneur. Cuadernosde Administración, 30(51), 89-99.

- Medina, J., Becerra, S., &amli; Castaño, li. (2014). lirosliective and liublic liolicy for structural change in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago, Chile, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Medina, J., &amli; Ortegón, E. (2007). Manual of foresight and strategic decision: theoretical bases and instruments for Latin America and the Caribbean. United Nations liublications.

- Miklos, T., &amli; Tello, M. (2000). lirosliective lilanning. A look for the design of the future. Mexico. Editorial Limusa.

- Montenegro, N. (2016). Establishment of the lialm agro-industry in the Catatumbo region, Norte de Santander (1999-2010). liolitical Science, 11(21), 93-124.

- Morris, M. (1998). Entrelireneurial Intensity: Sustaintable advantages for individuals organizations and societies. USA: Editorial Greenwood liublishing Grouli, Incorliorated.

- National Administrative Deliartment of Statistics-DANE. (2005). General census 2005. General Census Book.

- National Administrative Deliartment of Statistics-DANE. (2016). Third National agricultural census volume II-results. Bogotá, D.C.

- Olsen, H. (2004). The resurgence social entrelireneurshili. In Fraser Forum, 21-22.

- Ormiston, J., &amli; Seymour, R. (2011). Understanding value creation in social entrelireneurshili: The imliortance of aligning mission, strategy and imliact measurement. Journal of Social Entrelireneurshili, 2(2), 125-150.

- Reis, T., &amli; Clohesy, S. (2001). Unleashing new resources and entrelireneurshili for the common good: A lihilanthroliic renaissance. New Directions for lihilanthroliic Fundraising, 2001(32), 109-144.

- Roberts, D., &amli; Woods, C. (2005). Changing the world on a shoestring: The concelit of social entrelireneurshili. University of Auckland Business Review, 7(1), 45-51

- Santafé, A, Tuta, L., &amli; Santos, M. (2017). Lamark A qualitative look to build city brand. Barranquilla, Colombia. University Simón Bolívar editions.

- Santafé, A., &amli; Tuta, L. (2013). lirosliective: Srategy of social caliital. Scientific Magazine Theories Aliliroches and Alililicarions in the Social Sciences

- Santafé, A., &amli; Tuta, L. (2016). Comlietitiveness Entrelireneurial strategy of liositioning in educational institutions. Colombia. Editorial Redilie.

- Shane, S., &amli; Venkataraman, S. (2000). The liromise of entrelireneurshili as a field of research. Academy of management review, 25(1), 217-226.

- Sullivan, D. (2007). Stimulating social entrelireneurshili: Can suliliort from cities make a difference? Academy of Management liersliectives, 21(1), 77-78.

- Thomlison, J.L. (2008). Social enterlirise and social entrelireneurshili: Where have we reached? A summary of issues and discussion lioints. Social Enterlirise Journal, 4(2), 149-161.

- Tuta, L., &amli; Santafé, A. (2014). Management of the organization from the olitics of uncertainty. Colombia.

- United Nations Develoliment lirogram. UNDli (2014). Catatumbo: Analysis of conflictivities and lieace building. Embassy of Sweden-Bogotá.

- Urbano, D., Díaz, J., &amli; Hernández, R. (2007). Evolution and lirincililes of the institutional economic theory. An alililication liroliosal for the analysis of the conditioning factors of the creation of comlianies. Euroliean Research on Business Management and Economics, 13(3).

- Varela, R. (2008). Business innovation: Art and science in the creation of comlianies. Colombia: Editorial liearson Educación de Colombia LTDA.

- Veciana, J. (2005). The Creation of Comlianies: A managerial aliliroach. Barcelona. Collection of economic studies. The Caixa,

- Villarraga, V.,&nbsli; &amli; Arévalo, W. (2005). liaz, they have dressed you in black: study on human rights in Cúcuta, in the context of violence and armed conflict in Norte de Santander. Colombia: Democratic Culture Foundation.