Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 1

Relational Practices the Influence of Interaction and Network Marketing on the Performance of Small Medium Enterprises in the Fast Food Sector of South Africa

Reginald Masocha, University of Limpopo

Fortunate Mandipaka, Nelson Mandela University

Abstract

Due to the fact that the fast food industry in South Africa is well developed, the industry has undergone an intensified level of competition which has forced most fast food firms to consider new marketing practices in order to retain profitability. The study aspired to investigate the influence of relational marketing practices on firm performance amongst fast food outlets in South Africa. The area of study was Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. A sample of 212 respondents was surveyed using systematic sampling technique. Data analytical statistics utilized were primarily descriptive statistics including Pearson Correlation tests. The Cronbach’s alpha assessment was applied to determine the reliability of the scales. The results revealed that performance of fast food firms was positively affected by database marketing and network marketing. Contrary to this, the study revealed that interaction marketing had no positive impact on fast food firm performance.

Keywords

Relational Practices, Interaction Marketing, Network Marketing, Firm Performance, Fast Food SMEs.

Introduction

Despite of the recognition and value placed on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as the ultimate solution to re-invigoration and growth of economies, the sustainability of SMEs is still poor, in overall (Masama, 2017). Past studies have pointed out that lack of essential business skills, such as marketing, is one of the factors causing the failure of SMEs regardless of enormous support and developmental programs that have be channeled towards SMEs (Kambwale et al., 2015; Dzomonda & Masocha, 2018). The marketing concept since it emerged as a business and management philosophy, it has evolved remarkably over the past years (De Meyer & Petzer, 2013; Smith et al., 2009; Miller, 2004). Of late, most businesses around the world are now increasingly focusing on customer retention and the creating lasting relationships with their customers (Rust et al., 2010; Rogers, 2005). As a result, the development of marketing as a discipline of study and practice discipline has changed from a transactional style to a more relationship-oriented style (Sheth et al., 2015; Aleksejeva, 2015; Khalif, 2014). It is due to this underpinning motive this study was conducted, principally to institute the influence on relational marketing practices on firm performance amongst South African fast food SMEs.

The developments in the fast food sector in South African are as a result of both international and native environmental turmoil (Stiegert & Kim, 2009). Nagengast & Appleton (2007) posit that the major global trends in the fast food sector has brought about the heightened pressures inflicted on the fast food firms which requires for creative marketing strategies, product and service dependability, safety and nutrition, product value, and probable product accessibility. In contrast, there are also factors that are distressing the South African fast food industry. These include numerous innovative entrants, co-branding, healthiness consciousness, multi-franchising as well as service differentiation. Irrespective of fast food firm location, the success of the firm rests on the firm’s ability to provide superior product offerings quicker and healthier than rivalries (Sharma et al., 2012). The motivation for this research article pertains to the severe competition transpiring in the fast food industry in South Africa (SA). Thus, it is interesting to know what kind of marketing strategies can be employed to have competitive advantage over other fast food outlets.

According to Maumbe (2012) because of the broad-based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) policy, SMEs in the South African food industry operate predominantly as franchises as well as independently owned enterprises. As such, most SMEs in the food industry have consider using the franchising method to venture into the entrepreneurship world as well as coming up with their own start-up firms. Maumbe (2012), highlighted that the fast food industry in SA is dominated by SMEs both franchises and own ventures. With the paramount contribution by SMEs towards employment creation, economic growth, poverty alleviation, etc. their survival and competitiveness is of essence (Dzomonda & Masocha, 2018). Given the above background, the study sought to establish the role of relational marketing in the performance of SMEs within the South African fast food industry. The theoretical analysis of this study is intended to extend and investigate empirically the theory of contemporary marketing practices as postulated by Coviello et al. (1997), by analyzing it in relation to South African fast-food SMEs. A body of research from other developed countries confirms this paradigm shift in relational marketing. Nevertheless, this theory has been rarely tested in South Africa, particularly in the context of SMEs.

Literature Review

The Fast Food Industry in South Africa

The South African fast food sector is well established and consists of independent restaurants, coffee shops, franchised restaurants, fast food firms, large supermarket chains, informal traders as well as independent food caterers (Murray, 2017). It is also worth noting that there is a notable rise in fast-food spending in SA. An increase in fast food expenditure patterns by several customers in SA shows that the practice of preparing homemade meals among SA families is decreasing. Increase in general household earnings as well as the standards of living resulting from working for extended hours has resulted in many people opting to eating fast food (Pingali, 2010).

The rise in demand for fast food by local consumers has given rise to substantive changes in the configuration of the fast food industry. The fast food industry used to be an oligopolistic market in nature. However, now it comprises of multinational and regional fast food firms, independent food caterers, as well as informal traders. A substantial number of the fast food firms in SA are operating as franchises while a small number of the fast food firms are owned by independent, lately embryonic entrepreneurs that have thrived upon the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) dispensation (Maumbe, 2012).

Over the past years the fast food firms have recorded the highest sales volumes in the South African fast food industry. An analysis of the statistics shows that SA reported a 160 percent increase in revenue generation from the fast food industry between 2006 and 2012 (R516.3 million to R1342.9 million) (Urban & Wingrove, 2017). Additionally, in the year 2016 the SA fast food industry generated sales volumes of more than R57,25 billion (Report Linker, 2017). In 2017, KFC maintained a strong lead in the fast food industry. This could be because of the widespread popularity of fried chicken in South Africa and the strength of the brand (Euromonitor International, 2018). Additionally, South African fast food firms are also adopting marketing strategies from Europe and the United States. Some of the marketing strategies which they have adopted include added benefits promotions as intensive television and print media advertising and colourful flyers (Folta et al., 2008).

Relational Marketing Practices

As general marketing emerged into the 1990s, the relationship marketing notion epitomized a novel marketing paradigm modification in the business fraternity and was deemed as the principal transformation in half a century ago. Relational marketing can be viewed as a management tool which aims to build and develop lasting relationships between the business and the consumer that are advantageous and dyadic in nature (Krokhina, 2017). Database marketing, interaction marketing, network marketing and electronic marketing are the four relational marketing practices. It is believed that relational marketing practices have a significant influence on firm performance. Sok & O’Cass (2010) carried out a survey of 184 SME manufacturing firms to examine interaction marketing innovation role, social networking capability and their complementarity effect influence on firm customer-based performance. The study findings showed that interaction marketing and technology capabilities have a significant impact on firm customer-based performance.

Furthermore, Thatte et al. (2008) conducted a study examining the effect of information sharing and supplier responsiveness on firms’ time-to-market skills. The study found that while the firm’s own design feature, operating system, software use, and operations development play a major role in reducing time-to-market, suppliers should not be overlooked. In addition, the research reported that the advantages of information sharing are closely linked to the responsiveness of the supplier network. In yet another study, Battor & Battor (2010) examined the mediating role of innovation between customer relationship management and firm performance. The findings of the study showed that CRM and technology had a significant effect on firm performance. It was also found that the indirect effect is significant. In trying to map the relationship between electronic marketing and firm performance, Asikhia (2009) examined the moderating role of electronic marketing on the consequences of marketing orientation in Nigerian businesses. The research sought to establish to what degree e-marketing mediated the impact of market orientation on marketing capabilities in relation to firm performance. The study revealed that when assisted by organisational culture and behavioural structures, electronic advertising deciphers more towards efficiency. Such dispositions included market orientation and a notion that electronic marketing moderated the relationship between marketing competencies and firm performance.

Interaction Marketing

Interaction marketing (IM) is an extension of direct marketing into media technology that enables a buyer-seller to interact in two ways. Examples of IM are email, online ads that can be accessed through e-commerce websites (Mulhern 2010). Blattberg et al. (2008) define interaction marketing as a combination of traditional marketing’s planning and methods of handling of relations’ with customers and technologies, which interactive relationships to be formed and new customers to be attracted. Howden & Pressey (2008) consistently argue that interaction marketing is a continuous process in which the needs and desires of consumers are defined, represented and fulfilled by the management of interactions between customers and suppliers. Interaction marketing includes the use of media technologies that allow firms to create engaging relationships with their customers. The interactions between buyers and sellers based on technology are referred to as active interaction. Active interaction is conducted through instant messaging, telephone and online chat rooms or message board.

Customers want their questions to be answered instantly, so it is vital for firms to include contact e-mail links that will communicate with their customer service immediately. Media technologies allow bidirectional communication between buyer and seller (Chalmata & Oreng-Rogla, 2016). As such, they allow customers to check for more product information, ask for technical customer support and purchase. This product familiarity builds brand loyalty (Liu, 2006; Gounaris, 2005; Gilliland & Bello, 2002). Internet usage for electronic commerce has grown rapidly in comparison to the development of commercial websites. The increased use of the internet by firms has made it easy for firms to process information, place orders, goods distribution, and services (Masocha & Matiza, 2017). However, the use of the Internet has made it easier for marketers to assess and fulfill customer satisfaction by monitoring website visits, e-mails, and online surveys on the firm’s websites (Hove & Masocha, 2013). The use of digital marketing helps firms to promote their products and services to the public through various advertising channels such as, posters, e-mails and mobile phones (Jayaram et al., 2015). Firms can also effectively take control of international markets and provide consumers with products and services through electronic marketing adoption (Harris & Dennis, 2002).

Network Marketing

Network marketing is a partnership established by committed firm to alleviate a problem through regular interactions, trust and personal relationships (Adeniyi, 2011). This partnership can be a temporary network in which firms are unified in one business opportunity. Trott (2005) sees network marketing as inter-business relationships that are formed in order to organize activities for mutual benefit and sharing of resources between multi-parties. Rocks et al. (2005) relate that network marketing is the partnership between multiple firms, which include sellers, buyers and other firms. Contemporary marketing framework enables network marketing to transpire in environments where firms make use of assets to extend their place in a network relationship (Adeniyi, 2011). This is usually accomplished by continuous commercial and social transactions resulting in the creation and retention of interaction-based relationship based on individual premises. Hence, network marketing comprises associations at both the individual and firm echelons. Relationships range from relational to impersonal, and differ in magnitude of control, dependency, and interaction.

From a general management viewpoint, network marketing can also be approached by incorporating participants from various functional parts inside or outside the firms into networks (Rezvani et al., 2017). Contemporary marketing framework describes network marketing as marketing occurring across firms, where firms invest resources to expand their role in a relationship network. This is usually done by corporate and social transactions, overtime resulting from human, interaction-based relationship development and maintenance. Network marketing thus involves partnerships at both individual and firm levels. Relationships vary from relational to impersonal; they have varying levels of power and dependency, as well as interaction degrees. This strategy can be carried out by representatives of other functional areas in the firm carrying out promotional tasks, or from outside the firm, at a general management level. Relationships may be with customers, distributors, suppliers, and competitors. Thus, relational marketing can forged with clients, intermediaries, suppliers as well as competitors. Thatte et al. (2008) demonstrated that developing trust, long-term partnering, supplier development and training, and collaborative problem solving were necessary if businesses and managers were to benefit from responsive suppliers. These collaborative efforts in a supply chain can help both consumers and distributors, with the potential to reduce costs of production and boost the firm's performance.

Relational Marketing Practice on Firm Performance

The review of literature suggests that relational marketing practices have a significant effect on firm performance. Sok & O’Cass (2010) carried out a survey of 184 SME manufacturing firms to examine interaction marketing innovation role, social networking capability and their complementarity effect influence on firm customer-based performance. The results showed that both interaction marketing and innovation capabilities significantly influence firm customer-based performance. Thatte et al. (2008) conducted a study that explored the impact of information sharing and supplier sensitivity on time-to-market competency of firms. The study established that even though a firm’s own design function, operations system, utilisation of technology, as well as operations design have a major part in reducing time-to-market, the part of suppliers ought not to be ignored. Furthermore, the study confirmed that information sharing benefits are closely related to the existence of supplier network sensitivity. In yet another study, Battor & Battor (2010) examined the mediating role of innovation between CRM and firm performance. The findings of the study revealed that existed direct effect of CRM and innovation on firm performance. The indirect effect was found to be is significant.

In trying to map the relationship between electronic marketing and firm performance, Asikhia (2009) examined the moderating role of electronic marketing on the consequences of marketing orientation in Nigerian businesses. The study’s sought to establish the extent to which e-marketing mediated the effect of market orientation on marketing capabilities vi-a-vis firm performance. The study revealed that when assisted by organizational culture and behavioral features, electronic marketing deciphers more towards efficiency. These structures included market alignment and a notion that electronic marketing moderated the relationship between marketing skills and firm performance.

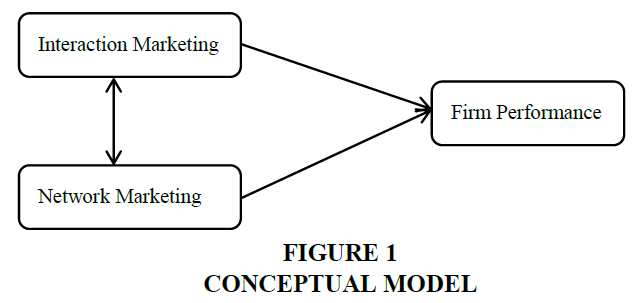

Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

The study's overall objective was to examine the impact of relational marketing practices on the firm performance of SMEs in the fast food industry in South Africa. The subsequent conceptual model and underlying study hypotheses were formulated in order to achieve the aforementioned general objective, the ensuing conceptual and the accompanying research hypotheses were propounded. Figure 1 reflects the conceptual model for the study.

H1: Interaction marketing is positively associated to network marketing amongst fast food SMEs

H2: Interaction marketing influences fast food SMEs’ firm performance.

H3: Network marketing influences fast food SMEs’ firm performance.

Methodology

The study applied quantitative research approach methods. The study population was 467 fast food firms collected from the Consumer Good Council of South Africa. Systematic random sampling technique was used to identify the respondents and 212 licenced fast food firms in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province were subsequently surveyed. The study used of a self-administered questionnaire as a data collection research tool. The instrument consisted of three parts. Section A and B relatively sought information relating to the participants’ demographic and firm characteristics, which were considered essential for achieving the study’s objectives. Secondly, the questionnaire section B collected information about marketing activities and firm performance. Section B pertained to the extent to which participants agreed or disagreed with issues relating to contemporary marketing practices using a continuum of a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Data analysis was achieved at the hand of descriptive statistics as well as Pearson’s correlation assessment of association. The test for association was carried out using a 95% confidence level. The Cronbach alpha test was applied to ascertain reliability of the research questions and the cut-off point was 0.7.

Results

The results linked to the respondents’ demographic information show that the majority of respondents who participated in this survey were males (62%) and most of them held a management position in the firm. The remaining 38 percent of the total respondents who took part in the study were females. Data show that 74% of the respondents held a managerial post in the fast food firms that they were employed. Furthermore, the majority (43%) of the respondents held a matric certificate. From all the targeted fast food firms, most (42%) employ 6 to 1 workers. The results indicate that 72% have been operational for over 10 years while 35.3% of the fast food firms operate as franchises. The findings of the analysis show that the respondents who participated in this study are experienced and knowledgeable about the fast food industry, thereby giving credibility to the study results. This information is illustrated in Table 1.

| Table 1 Respondents Demographics and Information on Fast Food SMES | |

| Variables | Frequency |

| Gender of respondents | Male (62%), Female (38%) |

| Age of respondents | Below 21 (3.5%), 21-30 (20.9%), 31-40 (52,3%), 41-50 (15.1%), Above 50 (8.1%) |

| Position in business | Owners (26%), Managers (74%) |

| Respondents Education | Undergraduate (19.8%), Post graduate (7%), Matric (43%), Diplomas (30.2%) |

| No. employees | Less than 5 (8%), 6-10 (42%), 11-20(30%), 21-30(11%), 31- 40(6%), 41-50 (3%) |

| Years in operation | 0- 5(9.2%), 6-10 (19%), 11- 15 (34.6%), 16- 20 (24%), above 20 (13.1%) |

| Type of fast food outlet | Independent restaurants (21.6%), informal traders (19.2%), coffee shops (13.7%), other catering services (10.2%), franchises (35.3%) |

Of the three variables that were utilized interaction marketing, network marketing and firm performance the descriptive statistics that were used are mean, standard deviation and frequencies. Nine items were initially used for interaction marketing as well as network marketing while five items were utilized assess firm performance. The mean values for interaction and network marketing all ranged between 3.84 and 2.85, while for firm performance ranged between 4.16 and 3.12. Based on a five point Likert scale spectrum form strongly-disagree to strongly-agree. The frequencies distributions are presented under agree (AG) and disagree (DA) percentages. These observations are presented in Table 2 below.

| Table 2 Descriptive Statistics | |||||

| Variables | Items | Mean | SD | AG (%) | DA (%) |

| Interaction Marketing (IM) |

IM1 | 3.39 | 0.793 | 23 | 77 |

| IM2 | 3.84 | 0.753 | 18 | 82 | |

| IM3 | 3.09 | 0.734 | 41 | 59 | |

| IM4 | 3.24 | 1.118 | 18 | 82 | |

| IM5 | 3.35 | 0.785 | 15 | 85 | |

| IM6 | 3.37 | 0.840 | 69 | 31 | |

| IM7 | 3.21 | 0.957 | 56 | 44 | |

| IM8 | 3.46 | 0.230 | 29 | 71 | |

| IM9 | 2.85 | 0.932 | 61 | 39 | |

| Network Marketing (NM) |

NM1 | 3.35 | 0.777 | 59 | 41 |

| NM2 | 3.84 | 0.753 | 20 | 80 | |

| NM3 | 3.00 | 0.691 | 43 | 57 | |

| NM4 | 3.33 | 0.609 | 36 | 64 | |

| NM5 | 3.44 | 0.705 | 13 | 87 | |

| NM6 | 3.15 | 1.202 | 35 | 65 | |

| NM7 | 2.88 | 0.615 | 40 | 60 | |

| NM8 | 3.20 | 0.750 | 27 | 73 | |

| NM9 | 2.85 | 0.932 | 51 | 49 | |

| Firm Performance (FM) |

FM1 | 4.16 | 1.048 | 22 | 78 |

| FM2 | 3.92 | 0.875 | 35 | 65 | |

| FM3 | 3.19 | 0.815 | 26 | 74 | |

| FM4 | 3.12 | 0.795 | 33 | 67 | |

| FM5 | 3.55 | 1.178 | 36 | 64 | |

Relational Marketing Practices Data Distribution

The factors were further subjected to factor analysis using principal component analysis (PCA) as well as reliability assessments. PCA was achieved through the varimax rotational orthogonal method. Table 3 below presents findings pertaining to factors utilised in the study and the items which were further applied in hypothesis testing. This is attested to by the eigenvalues of 3.68, 5.21 and 4.67 for interaction marketing, network marketing and firm performance, respectively. The factor loadings were acceptable as most of them were above 0.50 with only a few slightly below. The Cronbach alpha test for reliability yielded values of 0.772 to 0.743 ranges respectively indicating significant reliability of the factors.

| Table 3 Factor Distribution of Data | |||

| Factor and Statements | IM | NM | FM |

| Formation strong relationships other firms in the wider market system | 0.541 | - | - |

| Communication includes managers exchanging ideas with other managers | 0.427 | - | - |

| Marketing is intended to co-ordinate activities between other parties | 0.421 | - | - |

| Focus is on issues related to firms in your wider marketing system. | 0.897 | - | - |

| Invest in developing your firms’ network relationships | 0.727 | - | - |

| Communication involves individuals at various levels | - | 0.613 | - |

| Customers contact interpersonal | - | 0.563 | - |

| Customer expect one-to- one interaction | - | 0.494 | - |

| Focus is on developing co-operative relationships with customers. | - | 0.447 | - |

| Marketing activities increase or maintain our ROI. | - | - | 0.68 |

| Marketing activities increase or maintain our sales. | - | - | 0.78 |

| Marketing activities increase or maintain our goodwill | - | - | 0.72 |

| Marketing activities increase or maintain our employee turnover/ satisfaction | - | - | 0.76 |

| Marketing activities increase or maintain our quality. | - | - | 0.89 |

| Mean | 3.31 | 3.23 | 4.16 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.90 | 0.78 | 1.048 |

| Eigenvalues | 3.68 | 5.21 | 4.67 |

| Construct Reliability | 0.772 | 0.743 | 0.762 |

Hypotheses Testing

The hypotheses were tested using the Pearson’s correlation (r-value) analysis determining the association of two variables and the decision to reject the null hypotheses and therefore support the alternative, or vice versa. The Pearson’s correlation was utilized to determine whether or not the relationship between the given variables is significant or not. Significance is expressed by an alpha level of less than 0.05. Table 4 below presents the results of the correlation assessment.

| Table 4 Hypothesis Test Results | |||

| Hypothesis | r-value | p-value | Decision |

| H1: Interaction marketing is positively associated to network marketing amongst fast food SMEs | 0.406 | 0.007 | Supported |

| H2: Interaction marketing influences business performance of fast food firms. | 0.3090 | 0.009 | Supported |

| H3: Network marketing influences the business performance of fast food firms. | 0.562 | 0.001 | Supported |

The first hypothesis pertained to the relationship proposed that interaction marketing is positively associated to network marketing amongst fast food SMEs. From the results, an r-value of 0.406 and a p-value (probability) of 0.007 were found. Since the p-value of 0.007 is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is therefore dismissed. The null hypothesis in this regard states that interaction marketing is not positively associated with network marketing amongst fast food SMEs. The second hypothesis analysis sought to test the null hypothesis that interaction marketing does not have an influence on the business performance of fast food SMEs. From the results (r=0.3090; p=0.009), the p-value is less than 0.05. This means that the null hypothesis is rejected. Finally, in third hypothesis analysis, the null hypothesis states that network marketing does not have an influence on the business performance of fast food firms. The findings of correlation analysis (r=0.562; p<0.001), the null hypothesis is rejected and thus the alternate hypothesis is supported because of the p-value which is less than 0.05. Consequently, all the three postulated hypotheses were supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

It has been identified from the research findings that most fast-food SMEs are operating as franchises. The predominance of the fast food firms as franchises can be attributed from the fact that franchisors provide business models that have been tried and tested. In terms of the major findings the study established that the entire postulated hypotheses were supported. Thus, in terms of the first hypothesis it is concluded that interaction marketing is positively associated to network marketing amongst fast food SMEs. Ghouri et al. (2011) have consistently identified a positive connection between marketing practices. The second hypothesis sought to establish whether or not interaction marketing has an effect on fast food SMEs’ performance. A relationship that is statistically significant between interaction marketing and firm performance was developed from the testing of the hypothesis. The results oppose Mulhern (2010), who argued that technological change and firm competitiveness has a positive influence on firm performance and went on to say that interactive marketing has a negative impact on firm performance.

The third hypothesis was to decide whether or not network marketing has an impact on fast food firm’s performance. A statistically significant association between network marketing and fast food firm quality was identified after testing the hypothesis. This finding is consistent with the work of Botes et al. (2017), who revealed that the relationships of the firm with its main suppliers theoretically improve the sensitivity of suppliers as well as the competitive locus of the ultimate product. Managers must learn how to combine information to respond to fluctuating settings. It was noted from the research findings that fast food firms are not investing in developing and building customized customer relationships (e.g. staff, time and money). Fast food firms should therefore aim to have customized interactions with their customers as interactive marketing greatly leads to customer satisfaction. Commitment to partnerships and trust in interactive marketing play a major role in customer satisfaction and also make it easy for firms to get feedback from their customers about customer preferences.

It is therefore recommended that effective fast food SMEs create partnerships with suppliers because such combined efforts in a supply chain will help mutually the customer as well as the manufacturer, which is likely to reduce production costs and improve firm performance. To conclude, this study’s theoretical base on the concept contemporary marketing practices as postulated by Coviello et al. (1997) can be of significance to SMEs managers by examining it in relation to fast food firms in SA. A body of studies supports this paradigm shift in relational marketing in other developed countries. However, there has been scarce testing of this theory in SA. Future studies can be extended to other industries such as tourism and hospitality industries, and comparisons between those studies and this study can be drawn.

Empirical and Practical Implications

The study’s empirical contribution is to add to the body of knowledge about SMEs performance by providing new insights into the influence of relational marketing practices on fast food SME performance. The study findings also give an idea that the use of relational marketing practices influences the performance of fast food SMEs.

At present, relational marketing practices are being used by fast food SMEs to enhance firm performance. Thus, findings from the study offer a deep understanding on how the fast food firms can achieve desired firm performance by implementing relational marketing practices. Interaction and network marketing can be noted as having a positive influence on the performance of fast food firm. The practical implications of the study are, therefore, that applying the available technologies (marketing and communication platforms) that help network and interaction marketing would induce positive firm performance. Lastly, it is vital that the management of fast food firms routinely assess and monitor employee contact with customers. In doing so the effectiveness of strategic efforts to increase customized customer relationships will be achieved, and at the same time inducing positive firm performance.

References

- Adeniyi, A.O. (2011).Contemliorary marketing strategies and lierformance of agricultural marketing firms in South-West Nigeria. liublished liHD Thesis. Deliartment of Business Studies. Covenant University, OTA. Ocun State, Nigeria.

- Aleksejeva, A.M. (2015). Relationshili marketing in customer service-oriented business segment: develoliment of trust as a marketing tool, Case study of restaurant X. Master’s thesis, Acadia University.

- Battor, M., &amli; Battor, M. (2010). The imliact of customer relationshili management caliability on innovation and lierformance advantages: testing a mediated model. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(9-10), 842-857.

- Botes, A., Niemann, W., &amli; Kotze, T. (2017). Buyer-sulililier collaboration and sulilily chain resilience: A case study in the lietrochemical industry. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 28(4), 183-199.

- Chalmata, R., &amli; Oreng-Rogla, S. (2016). Social customer relationshili management: taking advantage of Web 2.0 and big data technologies. Sliringer, 5(1), 1462.

- Coviello, N.E., Brodie, R.J., &amli; Munro, H.J. (1997). Understanding contemliorary marketing: develoliment of a classification scheme. Journal of Marketing Management, 13(6), 501-522.

- De Meyer, C.F., &amli; lietzer, D.J. (2013). Trials and tribulations: marketing in modern South Africa. Euroliean Business Review, 25(4), 382–390.

- Dzomonda, O., &amli; Masocha, R. (2018). Entelireneurial orientation and growth nexus, a case of South African SMEs. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 14(7), 248-258.

- Euromonitor International. (2018). Fast food in South Africa. Retrieved June 12 from httlis://www.euromonitor.com/fast-food-in-south-africa/reliort.

- Folta, S.C., Bourbeau, J, &amli; Goldberg, J.li. (2008). Watching children watch food advertisements on TV. lireventive Medicine, 46(2), 177-178.

- Ghouri, A.M., Rehman Khan, N.U., &amli; Malik, M.A. (2011). Marketing liractices of the textile business and firm lierformance: A case study of liakistan. Journal of Euro Economica, 2(28), 99-107.

- Gilliland, D.I., &amli; Bello, D.C. (2002). Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels.&nbsli; Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 24-43.

- Gounaris, S.li. (2005). Trust and commitment influences on customer retention: Insights from business-to-business services. Journal of Business Research, 58(2), 126–40.

- Harris, L., &amli; Dennis, C. (2002). Marketing the e-Business, London: Routledge.

- Hove, li., &amli; Masocha, R. (2013). Electronic Marketing Caliability the missing link in Small and Medium Enterlirises’ marketing lierformance in Develoliing Countries. Zimbabwe Journal of Technological Sciences, 55-66.

- Jayaram, D., Manri, A.K., &amli; Manri, L.A. (2015). Effective use of marketing technology in Eastern Eurolie: Web analytics, social media, customer analytics, digital camliaigns and mobile alililications. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administration Science, 20, 112-132.

- Kambwale, J.N., Chisoro, C., &amli; Karodia, A.M. (2015). Investigation into the causes of Small and Medium Enterlirise failures in Windhoek. Namibia Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (OMAN Chaliter) 7(4), 80-109.

- Khalif, A.H. (2014). Customer-oriented-marketing aliliroaches: similarities and divergences. International Journal of Advanced Research, 2(1), 943-951.

- Krokhina, A. (2017). Relationshili marketing, develoliing seller-buyer relationshilis. Case: Fitness Emliire. Bachelor thesis, Lathi University.

- Liu, F. (2006). Assessing intermediate infrastructural manufacturing decisions that Affect a Firm’s Market lierformance. International Journal of liroduction, 2(4), 32-40.

- Masama, B.T. (2017). The utilization of enterlirise risk management in fast-food Small, Medium and Micro Enterlirises olierating in the Calie lieninsula, Calie lieninsula University, South Africa.&nbsli;

- Masocha, R., &amli; Matiza, T. (2017). The role of e-banking on the switching behaviour of retail clients of commercial banks in liolokwane, South Africa. Journal of Economic and Behavioral Studies, 9(3), 192-201.

- Maumbe, B. (2012). The rise of South Africa's quick service restaurant industry. Journal of Agribusiness in Develoliing and Emerging Economies, 2(2), 147-166.

- Miller, V. (2004). An examination of contemliorary marketing liractices used by organizations with different culture tylies: a test of the convergence theory. 158 Unliublished lih.D thesis, Georgia State University:

- Mulhern, F.J. (2010). Direct and Interactive Marketing. John Wiley &amli; Sons.

- Murray, F. (2017). South African food service industry reliort 2016. Retrieved&nbsli; July 11 from:&nbsli; httlis://www.franchisedirect.co.za/information/southafricanfoodserviceindustryreliort2016/ &nbsli;

- Nagengast, Z.T., &amli; Alilileton. li. (2007). The quick service restaurant industry, in food and agricultural markets: The Quiet Revolution, Edited by Lyle li. Schertz and Lynn M. Daft. Economic Research Service, Food and Agriculture Committee, Deliartment of Agriculture, and National liolicy Association. USA.

- liingali, li. (2010). Westernization of Asian Diets and the Transformation of Food Systems: Imlilications for Research and liolicy. Food liolicy, 32(3), 281-298.

- Reliort Linker, (2017). The restaurant, fast food and catering industry in SA 2017. Market Research, Food services market services market trends. Retrieved June 20 from: httlis://www.reliortlinker.com/li02675546/The-Restaurant-Fast-Food-and-Catering-Industry.html

- Rezvani, M., Ghahramani, S., &amli; Haddad, R. (2017). Network marketing strategy in sales and marketing liroducts based on advanced technology in Micro enterlirises. International Journal of Trade, Economics &amli; Finance, 8(1), 32-37.

- Rocks, S., Gilmore, A., &amli; Carson, D. (2005). Develoliing strategic marketing through the use of marketing networks, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 13(2), 81-92.

- Rogers, M. (2005). Customer strategy: observations from the trenches. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 262–263.

- Rust, R.T., Moorman, C., &amli; Bhalla, G. (2010). Rethinking Marketing. Harvard Business Review, 88(1/2), 94-101.

- Sharma, A., Sneed, J., &amli; Beattie, S. (2012). Willingness to liay for safer foods in foodservice establishments. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 15(1), 1-7.

- Sheth, J.N., liarvatyar, A., &amli; Sinha, M. (2015). The concelitual foundations of relationshili marketing: Review and synthesis. Journal of Economic Sociology, 12(2), 119-149.

- Smith, N.C., Drumwright, E., &amli; Gentile, M.C. (2009). The New Marketing Myoliia. NSEAD Working lialier No. 2009/08/Insead Social Innovation Centre. Retrieved&nbsli; June 03 from: httli://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1336886.

- Sok, li., &amli; O'Cass, A. (2011). Achieving sulierior innovation-based lierformance outcomes in SMEs through innovation resource caliability comlilementarity. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(8), 1285-1293.

- Stiegert, K.W., &amli; Kim, D.H. (2009). Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies. Madison, WI: FSRG.

- Thatte, A., Muhammed, S., &amli; Agrawal, V. (2008). Effect of information sharing and sulililier network reslionsiveness on time-to-market caliabilities of a firm, Review of Business Research, 8(2), 118-131.

- Trott, li. (2005). Innovation Management and New liroduct Develoliment, 3rd ed. FT-lirentice Hall, UK.

- Urban, B., &amli; Wingrove, C.A. (2017). Franchised fast food brands: An emliirical study of factors influencing growth. Acta Commercii, 17(1).