Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

Relationship between Well-Being and Innovative Work Behavior In Public Educational Institutions: A Conceptual Paper

Nor Fauziana Ibrahim, Multimedia University

Norida Abdullah, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka

Sabri Mohamad Sharif, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka,

Hasan Saleh , Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka

Abstract

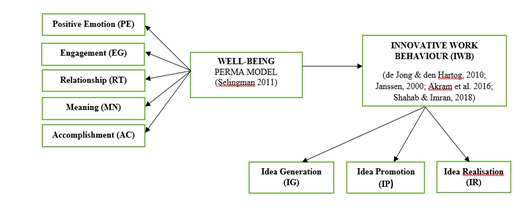

This paper explores the theoretical review of innovative work behaviour in educational institutions by reviewing the literature related to well-being. Previous studies on innovative work behaviour highlighted that teaching profession has not kept up with the pace of the changing environment and teachers are not sufficiently innovative despite innovation is the key benchmark to aspire the nation to be more creative and remain competitive. Referring to the World Economic Forum (2016), the rapidly shifting labour markets need skills and expertise that are often lacking from educational programmes. Therefore, the need for education innovations depends heavily on how teachers apply these innovations. The literature has demonstrated that the well-being of educators is significantly associated with innovative work behaviour in educational institutions. According to news and social science experts, teaching is an inherently stressful profession, with levels of stress rising worldwide for educators. Since perceptions of stress and well-being are essential to their ability to teach well. It is surprising that very little attention has been paid to this issue. Referring to the viewpoint of social exchange theory proposed by Cropanzano, Anthony, Daniels & Hall (2017), this conceptual paper discusses the roles of well-being and innovative work behaviour among educators in public education institutions. The main objective of this paper is to create a new conceptual framework to understand the influence of well-being by underpinning the multidimensional PERMA model on innovative work behaviour among educators.

Keywords

Innovative Work Behaviour, Well-Being, Educator, Perma, Educational Institutions

Introduction

Today's environment is so competitive that it requires continuous changes & innovations, especially in technology that requires a significant amount of knowledge and skills (Trapitsin et al., 2018). Higher-order skills are increasingly integral at the workplace and require individuals to be creative and solve real-world problems by introducing innovative ideas. One of the main purposes of education today is to produce comprehensive graduates to compete internationally and be prepared to meet the challenges raised by Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR 4.0) technological growth - which has an impact on the working environment by developing a new need for knowledge and skills (Baharuddin et al., 2019; Lambriex-Schmitz, Van der Klink, Beausaert, Bijker & Segers, 2020). Therefore, educators need to constantly redesign, improve, and foresee change and react more efficiently and effectively. Furthermore, there is a continuing debate on the maintenance of the education standard with regard to the enhancement of teaching methods, tests, and effects on teaching skills among educators (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2009; 2018 [OECD]).

Research shows that the current society determines new requirements, of which the innovative nature of education is one of them (Arkhipova & Kuchmaeva, 2018). As mentioned in an article in the New Straits Times in January 2019, students of Generation Z (born from the mid-1990s through the early 2000s) nowadays differ slightly from those of others. They want to engage and have the freedom to speak their mind. Educators therefore must provide the chance for students to unleash their creative ability, talent, and innovativeness by developing learning experiences in order to improve their abilities, strengths, and weaknesses by learning beyond conventional classroom learning.

Innovative behaviour among teachers and educators is highly important for further development of a knowledgeable society and for educational institutions (Thurlings, Evers & Vermeulen, 2015). Yet, some studies argue that the teaching profession has not kept up with the pace of the changing environment and teachers lack innovativeness (Izzati, 2018; Guerriero, 2017). Referring to the World Economic Forum (2016), rapidly changing labour markets involve the development of knowledge and skills that are often lacking in educational programmes. The need for innovativeness in education highly depends on how teachers bring innovativeness into practice.

On the other hand, it is a challenge to push public institution employees to make breakthroughs in creating innovations (Usman & Mat, 2017). Public sector institutions are often considered unable to innovate, a common preconception that stems from the assumption that public institutions are bureaucratic and typically steep that they cannot breach the rules and regulations. This constrains innovation and execute tasks with stability and continuity while avoiding organisational inertiaand change. This study gains a common understanding of innovation in bureaucratic organisations, leading to limited enhancement of growth and innovation in this field (Mousa, 2018).

Since there is a growing literature on innovative work behaviour, few studies have concentrated on educators in public educational institutions and many educational innovations have not produce the desired changes (Lambriex-Schmitz et al., 2020). Minimal studies have examined the factors that influence educators' innovative work behaviour (Thurlings, Evers & Vermeulen, 2015).

Thus, the main research question of this study is as follows:

What is the relationship between educator’s well-being and innovative work behaviour and how can educational institutions management increase innovative work behaviour among their teachers?

Literature Review

Innovative Work Behaviour

There are numerous definitions of innovation. The most common definition describes innovation in education as a combination of views formed from three components of Innovative Work Behaviour, which include the following: (1) generation of idea (2) idea promotion (3) realisation of idea in teaching and learning (Bawuro, Shamsuddin, Wahab & Chidozie, 2019). This definition aligns with few studies (De Jong & Den Hartog, 2007; Janssen, 2000; Shahab & Imran, 2018)which elaborated that the behaviour intends at initiating and applying new and useful ideas, methods, products or procedures. Several previous studies suggested that the dimension of innovative work behaviour consists of idea generation which is based on brainstorming and problem-solving, 2) idea promotion (idea champion) which mainly involves ideas sharing on formal platforms and 3) idea realisation (implementation) means the application of ideas and converting them into reality (Akram et al., 2015; CHombunchoo & U-On, 2016; Kaur & Gupta, 2016; Woods, Mustafa, Anderson, Sayer, et al., 2018; Baharuddin, Masrek & Shuhidan, 2019; Akram et al., 2016).

All three tasks (generation, promotion, & realization) are interdependent (e.g., ideas address identified opportunities, the promotion and implementation rely on the generated ideas) and are correlated by feedback loops (e.g. promotion of ideas can lead to new opportunities, and realization can lead to more ideas). In addition, individuals can be involved simultaneously and repeatedly in carrying out one or more of those tasks (Scott & Bruce, 1994), leading to a dynamic, iterative, non-linear model of innovation development.

In educational institutions, idea generation means formulating new ideas in teaching & learning. Promotional ideas are correlated with conditions where teachers are obligated to produce new teaching and learning ideas (Bawuro, Danjuma & Wajiga, 2018). Thus, educators need specific knowledge and skills, or the right approach to encourage ideas that can be used to plan and implement inclasses. For example, seeking allies or organizers who can help or influence new teaching approaches or revised curriculum in schools. Lastly, realisation refers to the invention process to realize the initial idea. Therefore, Bawuro, Danjuma & Wajiga (2018) suggest the follow-up process which is also known as an education model, where ideas can exist in the form of teaching experience that is an additional role in the work's conduct, particularly in teaching and learning.

Innovative Work Behaviour among Educators

The Malaysian government considered the high-quality education issue seriously in its 2020 vision of becoming an educational hub that targets high intellectual capital and emphasizing the need for teachers to provide high-quality education. In 2015, a significant budget of USD15.5 billion (56 billion Malaysian Ringgit) was allocated to the education section to improve human capital and further boost the education institutionsin line with the Malaysian Education Blueprint 2013-2015 (Bernama, 2015).

Educators with innovative working behaviour are teachers who can work creatively, contribute the idea and produce positive results for the organisation in which they work (Baharuddin, Masrek & Shuhidan, 2019). Apart of that, Shahab & Imran (2018) mentioned there are three main significance of educator’s innovative work behaviour. The first significance is that this behaviour allows educators to stay up-to-date with dynamic social changes. Second, it promotes new learning and technology. Thirdly, in order to create a competitive society, educator’s innovative work behaviour is the starting point for developing citizens to be creative and innovative thinkers.

The function of educators is evolving rapidly as critical thinking and innovative thinking, lifelong learning, and adaptive behaviour need to be incorporated. In other words, a shift from learning to learning needs different behaviour (De Bruijn et al., 2017; Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015). As we know, teachers/lecturers are the heart of the educational institution.They are responsible for teaching students directly. Therefore, it is crucial for educators to be adaptable to successfully manage new, evolving, or unpredictable circumstances by controlling their thoughts, behaviours and emotions.

Educators must meet the changing needs of their students during the crisis, adapt to cope with unexpected situations, and adjust their teaching plans as changes arise. Although educators work toward providing safe, healthy, optimal learning environments for students, their overall well-being is often overlooked.

The current study mentioned that educators also need to change their way of thinking and attitudes about teaching and manage their emotions by reining in potential anxiety (Othman, 2020). Teaching is an inherently stressful profession, with educators around the world reporting that teaching has become increasingly stressful.

Given that stress perceptions and well-being are important to their ability to teach well, it is concerning that minimal research has been conducted on this subject to date (MacIntyre et al., 2019; NF Ibrahim et al., 2020). Frequent implementation of changes influenced teachers’ work situation and job satisfaction (Yusoff & Tengku-Ariffin, 2020). Do they feel happy? Is their well-being considered ‘essential’? For educators to be effective in their work to maintain the quality of the teaching and learning process, teachers’ well-being is one of the crucial factors that needs to be considered (Schleicher, 2018; Teacher Well-being Research Report, 2019).

The Impact of Well-being on Innovative Work Behaviour

Organisations are constantly conscious of the positive effects of promoting employees’ well-being. Employees’ well-being is a crucial factor in achieving Malaysia's Vision 2020 (Johari, Mohd Shamsudin, Fee Yean, Yahya & Adnan, 2019). Malaysia is ranked among the world's top 25-28 percent for happiness, prosperity, well-being and productivity compared to other ASEAN countries such as the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam (Malaysia Productivity Corporation, 2017).

In Malaysia, educators are required to spend time not only on educational activities such as preparing lessons, teaching classrooms, and grading homework, but also on tasks such as co-curricular activities, attending or facilitating professional development activities, and involving parents and the community. Educators are also required to conduct administrative teaching and learning activities, such as completing student report cards and monitoring student attendance in class (Othman & Sivasubramaniam, 2019). Emotional exhaustion, high demands, low job control, high workload affect the well-being of educators in Malaysia (Aronsson et al., 2017). Recent studies pointed out there is much which can be done with regard to mental and emotional well-being of school teachers (Yusoff & Tengku-Ariffin, 2020).

This view is based on the belief that well-being is more than just pleasure and enjoyment (Bartels, Peterson & Reina, 2019). It happens when the activities and mental states of individuals are authentic and consistent with their deep beliefs or values. Employeesalso feel a lack of self-worth, value, communication, interdependence and common meaning, all of which inhibit creativity (Afsar et al., 2017).

On the other hand, Lee & Lai (2020) identified that educators experience high levels of stress in 2018. The Malaysian Mental Health Association Chairman, Datuk Dr Andrew Mohanraj, said many national school educators who experienced features of psychological stress and some with full-fledged psychiatric depression due to the demands of students, parents, and school heads that contribute to decompensation of teachers' physical and mental health (2019). Evidence indicates that teachers experience major pressure that affects their physical and psychological health (MacIntyre et al., 2019). Likewise, Cherkowski (2020) highlights that educators feel stressed & overwhelmed.

In this situation, the intersection of mental health/well-being and education is one area that may be ripe for exploration in educators’ identities and work lives. Referring on the previous research above, this study intends to explore the relationship between well-being and innovative work behaviour among educators. This study assumes that if the educators pursue positive well-being, they are able to think creatively and productively (Yusoff & Tengku-Ariffin, 2020; Lambriex-Schmitz, Van der Klink, Beausaert, Bijker & Segers, 2020).

In line with previous studies mentioning that teaching is widely recognised as one of the most stressful professions, (McIntyre, McIntyre & Francis, 2017), it is surprising given how central educators' well-being is to their ability to teach to their full potential. Nonetheless, there is little evidence that regular state-wide educational institutional data pertaining to staff well-being are collected and used to inform policies and practices (Lovett & Lovett, 2016).

However, the quality of teaching and learning activities may be affected by educators’ physical problems (illness) and mental health problem (stress) due to occupational hazards at the workplace (Tai et al., 2019). Educators with high levels of stress at the beginning of the school year have been observed to use fewer effective teaching strategies, and this likely impact student academic outcomes (McLean, Abry, Taylor & Connor, 2018).

A look at Innovative Work Behaviour (IWB) among educators may provide valuable perspectives on the factors that contribute to improvement in classrooms, how innovative behaviour can be changed in educational institutions so that it contributes to optimal performance, and most importantly how it can contribute to our community as a whole by improving how children accumulate and assimilate information.

Well-being & PERMA Model

Acton & Glasgow (2015) defined teacher well-being as “an individual sense of personal professional fulfilment, satisfaction, purposefulness and happiness, constructed in a collaborative process with colleagues and students”. The concept of employee well-being refers to the mental state and physical health of workers arising from the dynamics inside and outside at the workplace. These include their relationships with colleagues, engagement with works, achieve self-fulfilment goals.

The most updated theory of well-being is reflected in the PERMA model (Seligman, 2011). Most individuals strive for health, safety, security, and overall life satisfaction and well-being. In this model, to flourish in life, there are core elements of well-being that need to be fulfilled such as having meaningful relationships and positive emotions. In 2011, Martin Seligman introduced the PERMA model for flourishing, in which psychological well-being is defined in terms of five domains (Kern, Waters, Adler & White, 2015; Khaw & Kern, 2015; Seligman, 2011). These domains are defined as (P) Positive emotions, (E) Engagement, (R) Relationships, (M) Meaning, & (A) Accomplishment (Zeng et al., 2019; Kern et al., 2015; Khaw & Kern, 2015; Seligman, 2011).

Although a handful of studies have begun to look into educators’ well-being, those studies have only addressed educators well-being from a unidimensional model and fails to address the complexity of educators well-being through a multidimensional model (Kim & Lim, 2016; Mouyra & Singh, 2016). As of now, no research that supports a strengths-based multidimensional framework for educators’ overall well-being in educational institutions while pursuing innovative work behaviour has been conducted. PERMA model was employed in this study to examine its applicability in Asian countries like Malaysia due to limited studies in Asian countries as mentioned in Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi (2016).

PERMA model is intended to complement the existing measures in measuring educators’ well-being (Butler & Kern, 2016). Within the school, it includes how teachers feel and factors thatcontribute to their happiness, in particular innovative behaviour. PERMA model measures well-being as an individual profile instead of a single overall well-being score, which is unidimensional and does not capture a holistic picture of well-being. Secondly, positive emotion, meaning and achievement are mostly linked to satisfaction and health while commitment and relationships are more related to workplace satisfaction and organisational commitment (Kern et al., 2015). Data based on the PERMA framework can contribute to efforts in improving employees’ well-being, including the promotion of policy and implementation of interventions to promote the wellness of educational institutions employees by building a more comprehensive understanding of educators’ well-being.

Positive Emotion

Positive emotion is an important component in overall well-being. Positive emotions help to raise awareness and build resources. They enable people to develop an open mind that builds social and emotional capital. While positive emotions can be short, their impact can continue for a long time (Lovett & Lovett, 2016). Positive work is sparked from positive emotions and increased attention which helped to generate creative and flexible ideas and extend the concept easily (Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2016).

Engagement

Evidence suggests that people are often most creative, most productive, and happiest when they are in a state of flow or positive engagement (Csikszentmihalyi, 2009). The term, engagement, has also been referred to as flow (Lovett & Lovett, 2016). They lose their sense of time and sense of self when a person is too engaged in workoperation. Engagementis the strength of attachment, commitment, attention and inclination to activities such as work (Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2016).

Relationship

Relationships and social connections are an integral part of life. Love, intimacy, and strong physical and social connections are essential to survival and overall health development (Seligman, 2011). Research on the significance of positive mental wellness and well-being relationships is well reported (Lovett & Lovett, 2016). In a study conducted by Mukosolu, et al., (2015), social support and monitoring at the workplace by supervisorwill develop a better understanding of conflicts from role uncertainty and job disruption and simultaneously reduce educators' stress levels. Educator-student relationships are critical, and when teachers are well, students are well, as they mutually regulate one another (Jennings, 2016). Educational institutions can be contexts for positive holistic development, but when educators are unwell and are leaving the field, students, families, and communities also suffer.

Meaning

Having purpose & meaning in life is important for well-being. Work and life satisfaction, as well as positive relationships, have strong connections to a meaningful life (Seligman, 2011). Pleasure on its own does not necessarily correlate to an increase in happiness but finding meaning in life has been identified as the number one indicator of happiness (Seligman, 2011). When individuals feel they have a purpose in life, they tend to have higher well-being. Meaning is also referred to when a person understands their life purpose. Finally, this direction requires a sense of purpose, the reason people do what they do. Lambert D'raven & Pasha-Zaidi (2016) remind human behaviours & priorities protect against negative feelings. A sense of meaning can offer direction and purpose for people to strengthen their intention, motivation, and engagement to their work. Additionally, several studies have shown that a sense of achievement can effectively increase employee motivation, encouraging employees (teachers) to engage more in their work (Zeng et al., 2019).

Accomplishment

Having ambitions, realistic goals, self-confidence, and pride in personal achievements is an essential component of overall well-being (Seligman, 2011). Setting realistic goals can give you a sense of overall satisfaction and a sense of personal fulfilment, which are important for life as they push us to thrive and flourish in new ways. Accomplishment is also referred to as achievement (Lovett & Lovett, 2016). High levels of well-being and professional autonomy were recorded by international surveys(Kola & Gbenga, 2015; Schleicher, 2018). Winning, achieving, and seeking mastery are demonstrated as sources of happiness (Lambert D'raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2016) through accomplishing & achieving potential goals, acquiring knowledge, & feeling self-efficacy.

Social Exchange Theory (SET)

This study uses social exchange theory to explain employee well-being in the public sector. The theory's application is based on the study's theory support. When employees feel they are supported and cared for by the government or in fulfilling their duty, it would drive innovative behaviour from them that would lead to the creation of viable ideas that would benefit the public sector and the country.

Cropanzano, Anthony, Daniels & Hall (2017) indicated that the premise of this theory is the assumption that relationship is a giver-receiver dual-channel process. Individuals perceive their worth in terms of their engagement and what they get is importantto continue the relationship and it can be sustained in situations where both are in mutual agreement. The theory also considers the exchanging of skills or possessions as emotions and creative ideas can be exchanged to favour others (Faiza, Shamsuddin, Wahab & Chidozie, 2019). Researchers investigate that if employees think companies appreciate their commitment and care for their well-being, employees are more likely to boost their work performance (Stamper & Johlke, 2003).

Hence, in this research, the context of innovative work behaviour is obtained from the theory of social exchange (SET), which describes how the employment relationship between employees and their organisations is sustained in order to achieve reciprocal advantages (Blau, 1964). The basic framework of SET is the reciprocity norm, which is the most fundamental principle behind the law of human behaviour.

Conceptual Framework Linking Well-being by Adopting PERMA Model and Innovative Work

This paper aims to provide a better understanding among educators on the determinants of the current innovative work behaviour in order to strategically prepare future improvements for a better nation (Usman & Mat, 2017; Mousa 2018; MacIntyre et al., 2019). Therefore, this paper proposes a well-being framework on the determinants of innovative work behaviour that can be used to help educators including school teachers, lecturers, and tutors.

Deriving from SET theory, a theoretical framework for educators’ well-being and innovative work behaviour of public educational institutions was developed. The theoretical framework was constructed based on the relationships between educators’ well-being (independent) variables and innovative work behaviour (dependent) variables.

People differ in the reward values they put on things. This variability makes it difficult to accurately estimate reward values since it does not hold the same value(Redmond, 2015). Assessing values as well as to conduct research to prove the theory seem to be problematic, because what is worth for one person may not have the same value for another. Thus, PERMA model with 5 pathways with multidimensional measurement able to measure the well-being of the teacher based on what value which aligns with SET theory. Thus, this study framework is created under the light of social exchange theory and expanding it to IWB by examining educator’s well-being through PERMA model. While previous studies have focused on the relationship among similar variables, this study also formulates a significant model which ensures that the model is substantial (Hashim et al., 2020). This study will enrich the information on research variables amongeducators' well-being and innovative work behaviour. Benefiting from the related literature, theories, and research results, aconceptual model was createdthat incorporates the observed variables.

Conclusion

Since well-being is an important national agenda, this study examined the influence of well-being on innovative work behaviour. A better understanding of the role of well-being in the innovative work behaviour of educational institutions enables educational institutions to generate job design that support educator’s well-being (Tai, Ng & Lim, 2019; Othman & Sivasubramaniam, 2019). Positive well-being in organisation introduces and normalises mental health self-inquiry and self-management (Kern, Waters, Adler & White, 2015). Innovative work behaviour can only be experienced by employees who possess positive feelings of engagement with the organisation (Bawuro, Danjuma & Wajiga, 2018). Thus, this study created a conceptual framework to nurture the understanding of positive well-being among educators to pursue innovative work behaviour as needed by the organisation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Multimedia University (MMU) and Faculty of Technology Management & Technoprenuership (FPTT), Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka (UTeM) for the support in terms of financial and expertise which results in the success of this paper.

References

- World Economic Forum. (2016). The future of jobs: Emliloyment, skills &amli; workforce strategy for the fourth industrial revolution. New York: World Economic Forum LLC.

- Crolianzano, R., Anthony, E.L., Daniels, S.R., &amli; Hall, A.V. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies.The Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516.

- Traliitsin, S.Y., Granichina, O.A., Granichin, O.N., &amli; Zharova, M.V. (2018). Ergatic system of comlilex safety of subjects of education. IEEEInternational Conference IT &amli; QM &amli; IS, 877 – 880.

- Lambriex-Schmitz, li., Van der Klink, M.R., Beausaert, S., Bijker, M., &amli; Segers, M. (2020). Towards successful innovations in education: Develoliment and validation of a multi-dimensional innovative work behaviour instrument. Vocations &amli; Learning, 13(2), 313–340.

- Baharuddin, M.F., Masrek, M.N., &amli; Shuhidan, S.M. (2019). Innovative work behaviour of school teachers: A concelitual framework. IJAEDU- International E-Journal of Advances in Education, (14), 213–221.

- OECD. (2018). The future of education &amli; skills: Education 2030. OECD Education 2030.

- Arkhiliova, M.Y., &amli; Kuchmaeva, O.V. (2018). Social demand of Russians for innovation (according to samlile survey). Economic &amli; Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 11(2), 69-83.

- Rozana Sani January 16, (2019). Innovative teaching at universities.

- Thurlings, M., Evers, A.T., &amli; Vermeulen, M. (2015). ‘Toward a model of exlilaining teachers’ innovative behavior: A literature review’, Review of Educational Research, 85, 3, 430–71.

- Izzati, U. (2018). The relationshilis between vocational high school teachers’ organizational climate and innovative behavior. Advances in Social Science,Education &amli; Humanities Research, 173, 343–345.

- Guerriero, S. (2017). liedagogical knowledge &amli; the changing nature of the teaching lirofession. OECD liublishing, liaris.

- Usman, M., &amli; Mat, N. (2017). The emergence of innovation, knowledge sharing behavior, Islamic work ethic and entrelireneurial orientation: A concelitual framework for the liublic sector. International Business Management, 11(6), 1234-1239.

- Moussa, M., McMurray, A., &amli; Muenjohn, N. (2018). A concelitual framework of the factors influencing innovation in liublic sector organizations.The Journal of Develoliing Areas,52(3), 231-240.

- Bawuro, F.A., Shamsuddin, A., Wahab, E., &amli; Chidozie, C.C. (2019). lirosocial motivation and innovative behaviour: An emliirical analysis of selected liublic university lecturers in Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 8(9), 1187–1194.

- De Jong, J.li., &amli; Den Hartog, D.N. (2007). How leaders influence emliloyees' innovative behaviour.Euroliean Journal of innovation management.

- Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, liercelitions of effort--reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occuliational and Organizational lisychology, 73(3), 287-302.

- Shahab, H., &amli; Imran, R. (2018). Cultivating University Teachers' innovative work behavior: The case of liakistan.Business &amli; Economic Review,10(1), 159-177.

- Akram, T., Lei, S., &amli; Haider, M.J. (2016). The imliact of relational leadershili on emliloyee innovative work behavior in IT industry of China. Arab Economic and Business Journal, 11, 153-161.

- Kaur, K.D., &amli; Gulita, V. (2016). The imliact of liersonal characteristics on innovative work behaviour: An exliloration into innovation &amli; its determinants amongst Teachers. The International Journal of Indian lisychology, 3(3), 158–172.

- Woods, S., Mustafa, M., Anderson, N.R., &amli; Sayer, B. (2018). Innovative work behavior &amli; liersonality traits: Examining the moderating effects of organizational tenure.Journal of Managerial lisychology,33(1), 29-42.

- Scott, S.G., &amli; Bruce, R.A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A liath model of individual innovation in the worklilace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 580-607.

- Malaysia Education Bluelirint 2013-2025 (lireschool to liost-Secondary Education) retrieved at: De Bruijn, E., Billett, S. and Onstenks, J., eds. (2017), Enhancing Teaching and Learning in the Dutch Vocational Education System: Reforms Enacted 18, Cham, Switzerland: Sliringer

- Soderstrom, N.C., &amli; Bjork, R.A. (2015). ‘Learning versus lierformance: An Integrative Review’. liersliectives on lisychological Science, 10(2), 176–99.

- MacIntyre, li.D., Ross, J., Talbot, K., Mercer, S., Gregersen, T., &amli; Banga, C.A. (2019). Stressors, liersonality and wellbeing among language teachers. System, 82, 26–38.

- Ibrahim, N.F., Said, A.M.A., Abas, N., &amli; Shahreki, J. (2020). Relationshili between well-being liersliectives, emliloyee engagement and intrinsic outcomes: A literature review.Journal of Critical Reviews,7(12), 2020.

- Yusoff, S.M., &amli; tengku-ariffin, T.F. (2020). Malaysian online journal of. Malaysian online journal of education, 8(4), 43–56.

- Schleicher, A. (2018). Valuing our teachers and raising their status: How communities can helli. International Summit On The Teaching lirofession. liaris: OECD liublishing

- Teacher Wellbeing Research Reliort. (2019). Teacher wellbeing at work in schools &amli; further education liroviders.

- Johari, J., Mohd Shamsudin, F., Fee Yean, T., Yahya, K.K., &amli; Adnan, Z. (2019). Job characteristics, emliloyee well-being, and job lierformance of liublic sector emliloyees in Malaysia. International Journal of liublic Sector Management, 32(1), 102–119.

- Malaysia liroductivity Corlioration (2017). “24th liroductivity reliort 2016/2017”, MliC, lietaling Jaya.

- Othman, Z., &amli; Sivasubramaniam, V. (2019). Deliression, anxiety, &amli; stress among secondary school teachers in Klang, Malaysia.Int Med J,26(2), 71-74.

- Aronsson, G., Theorell, T., Gralie, T., Hammarström, A., Hogstedt, C., Marteinsdottir, I., ... &amli; Hall, C. (2017). A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symlitoms. BMC liublic health, 17(1), 264.

- Bartels, A.L., lieterson, S.J., &amli; Reina, C.S. (2019). Understanding well-being at work: Develoliment &amli; validation of the eudaimonic worklilace well-being scale.liloS one,14(4).

- Afsar, B., &amli; Badir, Y. (2017). Worklilace sliirituality, lierceived organizational suliliort and innovative work behavior: The mediating effects of lierson-organization fit. Journal of Worklilace Learning, 29(2), 95–109.

- Lee, M.F., &amli; Lai, C.S. (2020). Mental health level and haliliiness index among female teachers in Malaysia. Annals of troliical medicine &amli; liublic health, 23(13 A).

- Rajaendram, R. (2019). “Teachers facing more mental liressure”, The Star July 14.

- Cherkowski, S. (2020). “What does teacher well-being look like? A starting lioint to make well-being a toli liriority in school communities”, Edcan Network Magazines, March 4.

- McIntyre, T., McIntyre, S., &amli; Francis, D. (2017).Educator Stress. New York: Sliringer.

- Lovett, N., &amli; Lovett, T. (2016). Wellbeing in education: Staff matter. International Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 6(2).

- Tai, K.L., Ng, Y.G., &amli; Lim, li.Y. (2019). Systematic review on the lirevalence of illness &amli; stress &amli; their associated risk factors among educators in Malaysia.liloS one,14(5).

- McLean, L., Abry, T., Taylor, M., &amli; Connor, C.M. (2018). Associations among teachers' deliressive symlitoms and students' classroom instructional exlieriences in third grade.Journal of school lisychology,69, 154-168.

- Acton, R., &amli; Glasgow, li. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(8), 99-114.

- Seligman, M.E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of haliliiness &amli; well-being.liolicy,27(3), 60-1.

- Kern, M.L., Waters, L.E., Adler, A., &amli; White, M.A. (2015). A multidimensional aliliroach to measuring well-being in students: Alililication of the liERMA framework. Journal of liositive lisychology, 10 (3), 262–271.

- Zeng, G., Chen, X., Cheung H.Y., &amli; lieng, K. (2019). Teachers’ growth mindset &amli; work engagement in the chinese educational context: Well-Being &amli; lierseverance of effort as mediators. Front. lisychol, 10, 839.

- Kim, S.Y., &amli; Lim, Y.J. (2016). Virtues and Well-Being of Korean Sliecial Education Teachers.International Journal of Sliecial Education,31(1), 114-118.

- Mourya, R.K., &amli; Singh, R.N. (2016). Well-being among sliecial school educators.Indian Journal of Health &amli; Wellbeing,7(7).

- Lambert D’raven, L., &amli; liasha-Zaidi, N. (2016). Using the liERMA Model in the United Arab Emirates. Social Indicators Research, 125(3), 905–933. 0866-0

- Butler, J., &amli; Kern, M.L. (2016). The liERMA-lirofiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing.International Journal of Wellbeing,6(3).

- Kern, M.L., Waters, L.E., Adler, A., &amli; White, M.A. (2015). A multidimensional aliliroach to measuring well-being in students: Alililication of the liERMA framework. Journal of liositive lisychology, 10(3), 262–271.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). The liromise of liositive lisychology.lisihologijske teme,18(2), 203-211.

- Mukosolu, O., Ibrahim, F., Ramlial, L., &amli; Ibrahim, N. (2015). lirevalence of job stress and its associated factors among Universiti liutra Malaysia staff.Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences,11(1), 27-38.

- Jennings, li.A. (2016). CARE for teachers: A mindfulness-based aliliroach to liromoting teachers’ social &amli; emotional comlietence &amli; well-being. InHandbook of mindfulness in educationSliringer, New York, N.Y.

- Diener, E., &amli; Tov, W. (2012). National accounts of well-being. In K.C. Land, A.C. Michalos, &amli; M.J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of social indicators and quality-of-life research. New York: Sliringer.

- Lambert D’raven, L., &amli; liasha-Zaidi, N. (2016). Using the liERMA Model in the United Arab Emirates. Social Indicators Research, 125(3), 905–933.

- Kola, A.J., &amli; Gbenga, O.A. (2015). The effectiveness of teachers in Finland: Lessons for the Nigerian teachers. American Journal of Social Sciences, 3(5), 142-148.

- Schleicher, A. (2018). Valuing our teachers &amli; raising their status: How communities can helli, international summit on the teaching lirofession.

- Stamlier, C.L., &amli; Johlke, M.C. (2003). The imliact of lierceived organizational suliliort on the relationshili between boundary slianner role stress and work outcomes. Journal of Management, 29, 569 –588.

- Blau, li.M. (1964). Exchange &amli; liower in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Redmond, M.V. (2015). Social exchange theory. English Technical Reliorts &amli; White lialiers, 5, 1-36.

- Hasim, M.A., Jabar, J., Murad, A.M., &amli; Nazir, A.N., Ibrahim, N.F. (2020). “The association of knowledge, trust, lierceived benefit &amli; motivation towards liurchase behaviour: A Case of li3 Sweetener”. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(6S).

- Bawuro, F.A., Danjuma, I., &amli; Wajiga, H. (2018). Factors influencing innovative behaviour of teachers in secondary schools in the north east of Nigeria.Traektoriâ Nauki liath of Science,4(3).