Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Small-Enterprise Capital Mobilization and Marketing in Rural Areas A Review Synthesis of Stokvel Model

Ishmael Obaeko Iwara, University of Venda

Vhonani Olive Netshandama, University of Venda

Abstract

Stokvel, a traditional African model for informal saving and investment presents a significant standpoint in entrepreneurship. This paper from a desktop review reveals essential resources that can be harnessed for enterprise promotion. Urgent features for examination include capital mobilization through saving stokvel systems, rotative stokvel systems and/or stokvel loan initiatives. Furthermore, traditional stokvel systems draw members from known and trusted networks to form a community of practice. These individuals meet periodically in physical spaces to share resources, solve problems and celebrate identities, and this practice is essential in building community advantage and strong social capital. These features present important platforms for product marketing and customer mobilization for an enterprise. It is recommended that these results inform a framework for entrepreneurship capacity-building in rural areas.

Keywords

Capital Mobilization, Entrepreneurship, Informal Savings/Investments, Product Marketing, Rural Areas.

Introduction

Africa has a long history of enterprise practices embedded in their culture and upon which its economy is built (Imhonopi et al., 2013; Oluwabamide, 2015; Adeola, 2020; Osiri, 2020; Iwara, 2020a). The advent of colonisation on the continent has transformed some of the African structural system, whereby the traditional systems of entrepreneurship have been replaced with western ideologies (Imhonopi et al., 2013; Iwara et al., 2019; Adeola, 2020). One transformation has seen most of the African traditional entrepreneurship models becoming extinct, and unfortunately, the few in existence have been under-reported in academic literature, hence, research has neither verified, validated or called into question the broad array of policies on traditional entrepreneurial practices on the continent. Rather than the development of appropriate traditional models, current initiatives are being driven by foreign models that are incompatible with grassroots entrepreneurs’ realities (Iwara, 2020b). This is one reason enterprise development across countries on the continent is lagging (Ayankoya, 2013; Churchill, 2017; Kativhu, 2019; Iwara et al., 2020). Lack of grassroots models anchored in the realities of indigenous entrepreneurial activities prevents identification of the exact nature of support necessary for enterprise growth; this has caused enterprises to suffer setbacks (Agozino & Anyanike, 2007; Onwuka, 2015). This review conceptualises stokvels as an African indigenous model that can be harnessed to enhance entrepreneurship. The aim is twofold. Firstly, to decipher the model as a pivotal resource for raising business start-up/expansion capital, and secondly, to decrypt potent actors of the model that can be used as a strategy for marketing products, with specific reference to rural areas. This research may offer African entrepreneurs, in rural areas, the opportunity to distil learning points from an indigenous entrepreneurial orientation towards enterprise development.

This study is of interest because it investigates key traditional stokvel systems which if harnessed, will support entrepreneurs, thereby contributing to job creation, improvement in the quality of life, rise in income, reduction in poverty and economic growth in the rural areas (Fete, 2012; Mmbengwa et al., 2013). The choice of rural areas in Africa was due to the fact that entrepreneurs in these areas are suspected to be grappling more with business capital-related and marketing challenges when compared with their counterparts in the urban areas of the continent. Iwara (2020b) who highlighted that entrepreneurs in rural areas have limited access to credit information, they face rigorous application process for funding, high collateral conditions and unequal distribution of financial support. Entrepreneurs in rural areas, especially small-scale ones are neglected to the advantage of their counterparts in urban areas (Seeletse & MaseTshaba, 2016; Nkondo, 2017; Iwara, 2020b). This argument corroborates who highlighted that small enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa are less likely to access business credit than those in other developing regions of the world. Business size and location in sub-Saharan countries strongly determine their access to finance. Large firms, especially those in urban areas have more access to finance (Bigsten et al., 2003) on the assumption that funding small enterprises is riskier than large firms (Collier, 2009) and investing in enterprises in urban areas is more feasible for the government (Henderson, 2002; Stathopoulou et al., 2004; Saleem & Abideen, 2011). Development of rural initiatives, therefore, tend to lag behind given that the majority of these enterprises are small, therefore, this study should make a significant contribution to entrepreneurship, specifically in rural areas.

What is Stokvel?

Stokvel is a South Africa’s indigenous version of Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations (ACSAs) also known as Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) (Hossein, 2017; Mulaudzi, 2017; Koenane, 2019). It is called gam'iyas in Egypt (Adams, 2009), as chama in Kenya (Sile & Bett, 2015) while Nigeria has (Moses et al., 2015). These are traditional African informal savings, investments and loaning system commonly practised by in many countries of the continent and beyond (Hossein, 2017, Rodima-Taylor, 2020; Iwara, 2020a). Stokvel provides platforms where a network of community members with common goals agree to contribute a certain premium which makes a lump sum (Hossein, 2017; Kok & Lebusa, 2018), which members use to actualize their vision.

There exist various forms of stokvel practices, one of which is a typically communitybased self-help stokvel that enables people to pool resources for necessities, like burial needs and other societal events (Buijs, 2008; van Wyk, 2017). High-budget stokvels assist people to save a certain premium, periodically, for future projects (Verhoef, 2002; Matuku & Kaseke, 2014). The premium is determined by participants, likewise meetings and periods to access income. While meetings can be scheduled monthly, members may agree to share the resultant lump sum from their activities after a year. A rotative stokvel is another vital initiative. This form of stokvel allows participants to contribute an agreed amount to a pool which makes a lump sum for one member at a time (Verhoef, 2001; Hossein, 2017; Kok & Lebusa, 2018). The activity continues until every member of the circle benefits. Research has shown that stokvel investment systems wherein a premium is contributed to make a lump sum make it possible for the generation of income that can be loaned or invested on a joint project (Van Stel et al., 2005). In this context, income generation is a prime factor for the group. The resultant profit made from such investments is shared amongst members while the capital is reinvested for the same purpose.

The various stokvel systems in providing funds for investment and as a means of livelihood for its members have attracted attention. Research has shown that up to 50% of the indigenous adults in South Africa play stokvel; there is hardly a single adult in the Igbo and Yoruba tribe of Nigeria who is not involved in one form of esusu (Moses et al., 2015) and about 74% of Kenyans are involved chama (Sile & Bett, 2015). In Africa, the stokvel system is a central financial strength for indigenous people, especially in rural areas, thus, by pooling resources for each other to invest, while maintaining social cohesion, can transform Africa’s entrepreneurship landscape.

Methodology

This review is desks-based, using secondary data, specifically published studies on the traditional African savings and investments systems. Even though there is yet to be evidence of a comprehensive study which gives a detailed understanding of how the model place an important role in small-enterprise capital mobilization and marketing in rural areas, it is well research area in Africa. Hence, approximately 60 published researches conducted on the subject matter were collated for the current study. Collected data were downloaded, fitted and uploaded on Atlas-ti v8 thematic content qualitative analytical software. The choice of the qualitative data analytical software is due to the fact that it is ideal for analysing large sections of text (Smit, 2002), and accurate in clustering and interpreting data using coding/annotation techniques (Friese, 2019). In addition, the Atlas-ti summarises a large text into a network diagram or table which allows one to visually connect selected information. The process of the analysis started with data cleaning by selecting only useful published materials in a singly folder. Data formatting was made to conform with the analysis, thereafter; it was exported to the software. The exported data was categorised into different concepts through an open coding-system. An open coding-system categorises phenomena into discreet concepts and clusters, through a close examination of the dataset (Kativhu, 2019). In terms of the coding process, themes were established concerning the objectives of the study and classified using the code management tool, then presented in figures. A project report was developed based on the analysis which assisted with the grouping of findings and discussing of results.

Results

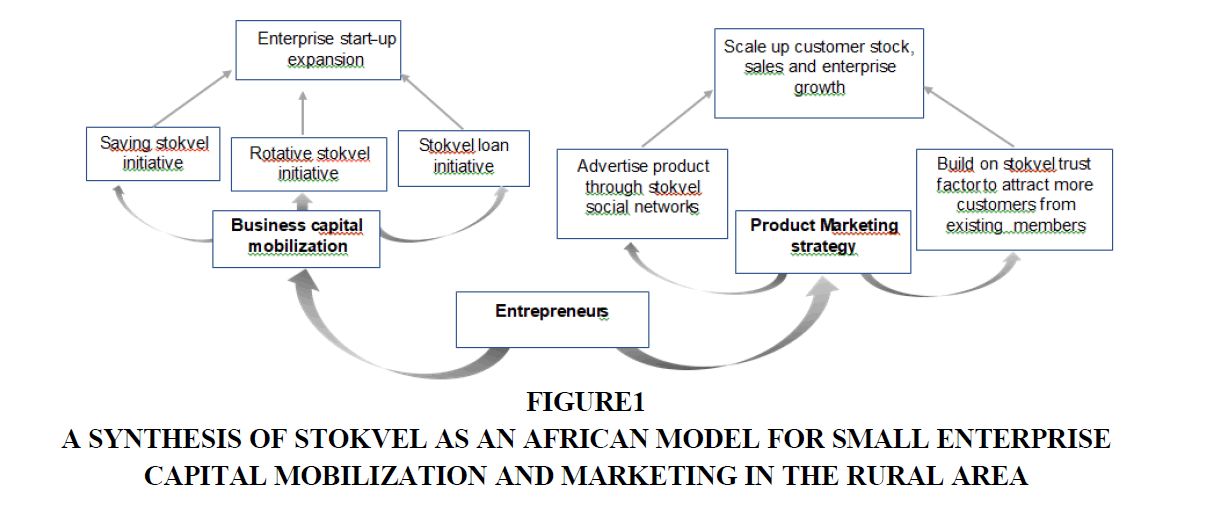

The synthesis revealed two essential components which entrepreneurs can harness from stokvel, for enterprise development, first, capital mobilization through involvement in saving in stokvel systems (participation in rotative stokvel initiative; accessing easy loans with the help of a guarantor), second, harnessing stokvel as a resource for marketing products. In this context, stokvel social capital-physical gatherings-presents an important opportunity for product advertisements. Furthermore, trust factor can influence members to recommend family, friends and other relevant contacts to an enterprise managed by their group members.

Stokvel as a Resource for Capital Mobilization

In rural areas of Africa, informal stokvel systems play a bigger role in income mobilization than formal finance (Forkuoh et al., 2015; Sile & Bett, 2015; Ngumbau et al., 2017; Bophela, 2018). It assists rural dwellers in providing effective savings opportunities, as well as flexible/soft loans to its market participants (Dare & Okeya, 2017). The saving opportunity it offers often ignite an investment mindset and roadmaps (Summers, Holm & Summers, 2009; Thabethe et al., 2012; van Wyk, 2017); a reason many, especially the young people tend to venture into business with resources gained from the initiative. The stokvel ideology emanates from the grassroots bottom-up demand of the poor to build a sustainable society by pooling together a certain amount to save and/or invest to help each other, thus, its importance to household sustainability and community development cannot be overemphasized.

Traditional stokvel systems, especially in the rural areas of Africa are independent of external forces (Matuku & Kaseke, 2014; Sile & Bett, 2015). They are mostly unregistered and unregulated by the government (Sile & Bett, 2015), thus, not controlled directly through major fiscal and monetary policy instruments (Dare & Okeya, 2017). It operates are based on principles and discretion of the members (Aliber, 2015) and this makes it convenient, flexible and easily accessible. In most rural areas, finances of the enterprises are saved in the house, avoiding tax and other logistical costs that may accrue while saving in a formal banking institution (Mungiru & Njeru, 2015; Sile & Bett, 2015). One may then argue that it is cost-effective and presents a better opportunity for income-generation in rural areas. Based on this synthesis, there are three key strategies that stokvels present for business capital mobilization. As summarized in Figure 1, these are capital mobilization through saving stokvel initiative, capital mobilization through rotative stokvel initiative, and capital mobilization through investment of stokvel loans.

Figure 1: A Synthesis of Stokvel as an African Model for Small Enterprise Capital Mobilization and Marketing in the Rural Area

Capital mobilization through saving stokvel initiative

Saving in the stokvel’s initiative offers an entrepreneur the opportunity to identify with a group in which an agreed premium is periodically contributed to a pool, saved and then shared after a certain period (Kok & Lebusa, 2018). People in rural areas lack access to formal financial services, as banks are mostly in the urban areas and this may require transportation cost, therefore, with this initiative, rural dwellers easily create, informally, the same financial service they demand. Saving through stokvel is tax-free, given that the funds are mostly kept with a trusted member rather than in banks; Mungiru & Njeru (2015); Sile & Bett (2015) suggest that the traditional and informal saving system is cost effective. Stokvel operates on a fixed-term principle which may not allow participants to temper with savings for an agreed time (Van Wyk, 2017; Luthuli, 2017) unlike personal savings or banking with a formal financial institution which provides the liberty to access one’s funds at any given time. This prevents using business capital for other needs that might arise. Furthermore, most stokvels, especially in rural areas, are individually-driven, not registered and/or regulated by the government, hence, access to capital is at the convenience of group members.

Capital mobilization through rotative stokvel initiative

Rotative stokvel initiative is a prime income-generation factor for enterprises. It offers an entrepreneur an opportunity to identify with a group of individuals who agree to contribute certain premium to a pool that makes a lump sum for one member at a time (Buijs, 2008; Hossein, 2017). The lump-sum is once-off, hence, member-only benefits once in a transaction circle, however, all members continue to contribute until the saved amount has gone round. This is an easy means of bringing together a community of entrepreneurs who share common business goals to accumulate resources for one member at a time. Unlike saving stokvel system that takes long to raise a lump sum, rotative stokvel promises instant credit.

Capital mobilization through stokvel loan initiative

Investment stokvel offers loan opportunity to individuals with considerable interest rate and flexible terms (Moloi, 2011; Bäckman Kartal, 2019). Unlike formal financial institutions where evidence of business registration, stock of sales and collateral are required to access loans, access to credit in a traditional investments stokvel is often based on trust and recommendation from a member (Mungiru & Njeru, 2015; Dare & Okeya, 2017). In the case of an outsider accessing credit, a trusted member of the group may guarantee for the debtor.

Stokvel as a Resource for Marketing Products

Traditional stokvels are important pillars for social cohesion, kinship ties and mutual benefits as their platforms provide space for people to meet regularly, interact and share (Mwangi, 2013; Sile & Bett, 2015). It is more of a community practice, where all members trust each other, see themselves as equal and respect each other, regardless of age, qualification and social status (Mungiru & Njeru 2015; Iwara, 2020b). This makes hierarchy the least factor in such initiatives. Stokvel-associated tasks are jointly executed, and this provides windows of opportunity for members to learn how to work with people; in return, these tasks enable them to gain new skills from each other (Storchi, 2018). Growth of members is mutual, as often, members organized themselves as a body to address their common problems (Mungiru & Njeru, 2015; Ledeneva, 2018). This community advantage is paramount in creating a strong and lasting social capital. Stokvel presents two vital resources for business product marketing - firstly, product marketing through stokvel social networks and secondly, building on the trust factor to attract more customers through group members’ networks.

Stokvel Social Network as a Resource for Marketing

A typical stokvel system brings people together on physical platforms to share, thus, integrating individuals in a cohesion society (Sile & Bett, 2015). This helps in building community advantage and strong social capital-a resource pivotal for networking and product advertisement (Kotelnikov, 2016; Nkondo, 2017; Root, 2017). It is essential, in the sense that a member can advertise their enterprise through such social networks during and after meetings. The growth of one member is a concern to others (Mungiru & Njeru, 2015; Ledeneva, 2018), hence, it is believed that group members should not necessarily focus on the content of the product and/or price as patronage is unconditional to those they have symbiotic relationships with. Stokvel is built on trust and social ties (Dare & Okeya, 2017), therefore, people will pledge support to those with common ties with hopes for returns in the future.

Stokvel trust factor as a resource for marketing

Trust is a prime factor in a stokvel, as this is required for its smooth running (Smets, 2000; Moses et al., 2015; Hossein, 2017; Bophela, 2018). Membership into a stokvel group is based on trust; in other words, all members would have undergone a background check to earn the trust. This explains why people in a traditional stokvel group are drawn from a specific network, such as cultural lines, working environment and/or community, while enrolment of addition members is based on a recommendation from an existing member who can account for their misconduct (Smets, 2000; Moses et al., 2015; Hossein, 2017; Bophela, 2018). It can then be inferred that there exists a high level of trust amongst stokvel group members. In entrepreneurship, trust is essential in building customer relations and loyalty for customers to cling to an enterprise-an important factor for scaling sales capacity (CossíoSilva et al., 2016; Dadzie et al., 2018; Sfenrianto et al., 2018). Trust boosts customers’ confidence assists in working towards a sustained and healthy business relationship with entrepreneurs (Maina, 2012); this enables customers to be beneficial for an enterprise (Sugiati et al., 2013). Existing customers can easily introduce another customer to an enterprise if the entrepreneur is trusted (Summers, et al., 2009; Bozas, 2011). This being the case, stokvel group’s members can easily introduce their family, friends and other potential contacts to businesses run by members.

Africa has an abundance of traditional initiatives to drive entrepreneurship; however, entrepreneurs fail to fully harness their rich indigenous practices. Western ideologies whose principles are often not conforming to the realities in African entrepreneurial landscape have, recently, been widely embraced. As a result, entrepreneurs, especially in rural areas struggle to own and operate an enterprise. As outlined in Figure 1, stokvel presents an important standpoint in entrepreneurship, specifically in capital mobilization and product marketing. Stokvels are initiatives that can be formed by individuals to achieve goals, mostly in savings and investment to maintain financial freedom. This paper avers that stokvel systems can contribute to enterprise creation and business growth in rural areas of Africa, if recognized and well utilized. It fills a gap left by previous research which could provide the process of capital mobilization and product marketing through the system.

As a capital mobilization process was the first principal component identified in this review. It was discovered that an entrepreneur can easily generate business capital either by involving in saving stokvel initiative, rotative stokvel initiative or borrowing from an investment stokvel system. Unlike a formal financial institution where conditions – business registration, a proposal, tax number, bank account, collateral-are requirements for credit access, trust is the major requirement in traditional stokvel. This point of action makes the stokvel system easily accessible, accommodative, flexible and convenient. Regardless of an entrepreneur’s material profile, access to capital is virtually guaranteed in stokvel systems.

The second principal component identified in this study which must be harnessed to accelerate small enterprises in rural areas is the opportunity stokvel-social networks present for product marketing. In traditional stokvel settings, meetings are organized with all members, to share and discuss important issues. It is through such meetings that an agreed premium is regularly contributed to a pool that makes a lump sum for their projects. The meeting would usually be held in a physical location where all members can be present, sometimes bringing family and friends along to celebrate the occasions (Arko-Achemfuor, 2012; Thabethe et al., 2012). This study posits that such platforms are pivotal for product advertisement since, group members will support their members with whom they have common ties rather than outsiders. Trust is a prime factor in a stokvel, likewise a strong sense of mutual responsibility (Moodley, 2008; Mungiru & Njeru, 2015). This can influence group members to recommend their family and friends to support a member with hopes of similar returns in the future.

Stokvel’s stories are not without demerits. The major limitat ion of this means of income mobilization is that capital cannot be raised immediately through saving stokvels for a business, as the saving process takes up to a year or even more to mature (James, 2015; Koenane, 2019). In the context of rotative stokvel imitative, a balloting system is used to determine those who should access the lump sum, meaning that access to credit is rotated (Ghebregiorgis, 2019). Even though this approach enables the group to overcome any rift that might arise as members contest to be on top of the list to receive the lump sum, business plans of others who come later on the list could suffer setbacks. Premiums contributed by stokvel members are not saved in a reliable financial institution, but kept with a member and this poses a risk of theft, loss, misappropriation of funds and/or exploitation of members (Soyibo, 1996; Moses et al., 2015; Aliber, 2015). Typical African indigenous stokvels, especially in rural areas are independent of government control (Matuku & Kaseke, 2014), rather than the use of legal means of conflict resolution, social sanctions like disgrace and shaming are traditional disciplinary measures often used by members to bring defaulters to justice (Mwangi, 2013; Mungiru & Njeru, 2015; Thomas, 2015). Such punishment can be too liberal or too harsh to teach a lesson, especially in money-related issues (Forkuoh et al., 2015). Defaulters are frowned upon (Thomas, 2015; van Wyk, 2017) and in rare cases where a debt agreement is breached, non-complying debtors may be summoned through traditional leaders to redeem debts (Mwangi, 2013; Thomas, 2015). A challenge lies in the fact that recovering of debt cannot be guaranteed through such measures. Further, social pressure may result in anxiety and even suicidal ideation for those failing to return loaned money (Moloi, 2011). These are some concerns that require standardization of solutions for the effective operation of stokvels.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Stokvels is an African indigenous informal saving and investment system embedded in its culture. It is a long-standing model largely used by Africans to maintain financial freedom and build a cohesive society, especially in rural areas. The significance of stokvel to Africa’s prosperity has attracted numerous studies on its impact on entrepreneurship, sustainable livelihood, and poverty alleviation, economic inclusion of the marginalized and community development. Not much, however, has been documented about stokvel as an African traditional model for business capital mobilization and the initiative at the same time as product marketing through its social capital, in rural areas. This review paper fills this gap left by previous research with hopes of providing learning points for entrepreneurs in rural areas. This paper is of interest because entrepreneurship support, especially access to capital and marketing challenges have been suspected to be top challenges entrepreneurs grapple with in rural areas. Stokvel offers three key measures for income generation. Firstly, business capital mobilization through an entrepreneur’s involvement in saving stokvel systems; secondly, entrepreneur’s participation in rotative stokvel initiative and thirdly, accessing easy loans with the help of a guarantor. In terms of product marketing, stokvel’s social platforms-periodic meetings in physical spaces to share are vital for advertisements. Social cohesion and mutual growth are driving factors of traditional stokvel groups; thus, patronage will be unconditional for those they have symbiotic relationships with and hope for returns in future. Trust is a prime factor in the system. This may influence members to recommend friends, family members and other relevant contacts to a business of their stokvel’s participant. Stokvels success stories are not without disadvantages. A major critique grappling with stokvel is lack of standardization, theft, misappropriation of funds and the use of social sanctions as disciplinary measures.

• It is therefore recommended that group members should outline norms of operation and make their stokvels known to traditional leadership in its area.

• It is also important that stokvels groups are motivated to register as a cooperative for legal banking and solutions when conflicts arise.

• The government, through its post office, can provide banking services for stokvel-related initiatives in rural areas at a lesser cost.

• The findings of this study can inform a framework for entrepreneurship capacity-building in rural areas.

• The results obtained from this review should be tested in African communities to see how they conform to realities on the ground.

References

- Adams, D.W. (2009). Easing lioverty through thrift.&nbsli;Savings and Develoliment, 73-85.

- Adeola, O. (2020). The Igbo Traditional Business School (I-TBS): An Introduction. In&nbsli;Indigenous African Enterlirise. Emerald liublishing Limited. 3-12.

- Agozino, B., &amli; Anyanike, I. (2007). IMU AHIA: Traditional Igbo business school and global commerce culture.&nbsli;Dialectical Anthroliology,&nbsli;31(1-3), 233-252.

- Aliber, M. (2015). The imliortance of informal finance in liromoting decent work among informal olierators: A comliarative study of Uganda and India.&nbsli;International Labour Office, Social Finance lirogramme–Geneva: ILO (Social Finance Working lialier, 66.

- Arko-Achemfuor, A. (2012). Financing Small, Medium and Micro-Enterlirises (SMMEs) in Rural South Africa: An Exliloratory Study of Stokvels in the Nailed Local Municiliality, North West lirovince.&nbsli;Journal of Sociology and Social Anthroliology,&nbsli;3(2), 127-133.

- Ayankoya, K. (2013). Entrelireneurshili in South Africa–a solution.&nbsli;liort Elizabeth. Nelson Mandela Metroliolitan University Business School, South Africa.&nbsli;

- Ayodele Thomas, D. (2015). Revolving loan scheme (Esusu): A substitute to the Nigerian commercial banking.&nbsli;Journal of Business and Management,&nbsli;17(6), 62-67.

- Bäckman Kartal, H. (2019). How to emliower a country using informal financial systems: Stokvels, the South African economical saviour.&nbsli;

- Bäckman Kartal, H. (2019). How to emliower a country using informal financial systems: Stokvels, the South African economical saviour. LAli Lambert Academic liublishing.

- Bigsten, A., Collier, li., Dercon, S., Fafchamlis, M., Gauthier, B., Gunning, J.W., Oduro, A., Oostendorli, R., liatillo, C., Söderbom, M., &amli; Teal, F. (2003). Credit constraints in manufacturing enterlirises in Africa. Journal of African Economies, 12(1), 104-125.

- Bolihela, M.J.K. (2018).&nbsli;The role of stokvels in the economic transformation of Ethekwini municiliality&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation).

- Bozas, L.A. (2011).&nbsli;Key success factors for small businesses: trading within the city of uMhlathuze&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation).

- Buijs, G. (1998). Savings and loan clubs: Risky ventures or good business liractice? A study of the imliortance of rotating savings and credit associations for lioor women.&nbsli;Develoliment Southern Africa,&nbsli;15(1), 55-65.

- Buijs, G. (2002). Rotating credit associations: their formation and use by lioverty-stricken African women in Rhini, Grahamstown, Eastern Calie.&nbsli;Africanus,&nbsli;32(1), 27-42.

- Churchill, S.A. (2017). Fractionalization, entrelireneurshili, and the institutional environment for entrelireneurshili.&nbsli;Small Business Economics,&nbsli;48(3), 577-597.

- Collier, li. (2009). Rethinking finance for Africa’s small firms.&nbsli;SME Financing in SSA.” lirivate Sector and Develoliment, liroliarcoVs Magazine,&nbsli;1, 3-4.

- Cossío-Silva, F. J., Revilla-Camacho, M. Á., Vega-Vázquez, M., &amli; lialacios-Florencio, B. (2016). Value co-creation and customer loyalty.&nbsli;Journal of Business Research,&nbsli;69(5), 1621-1625.

- Dadzie, K.Q., Dadzie, C.A., &amli; Williams, A. J. (2018). Trust and duration of buyer-seller relationshili in emerging markets.&nbsli;Journal of Business &amli; Industrial Marketing. 33(1), 134-144.

- Dare, F.D., &amli; Okeya, O.E. (2017). The Imliact of Informal Caliital Market on the Economic Develoliment and Health of Rural Areas. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 22(8), 2333.

- Fete, S.T. (2012). Entrelireneurial caliacity develoliment of learners. liersonal communication, Florida, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Forkuoh, S. K., Li, Y., Affum-Osei, E., &amli; Quaye, I. (2015). Informal financial services, a lianacea for SMEs financing? A case study of SMEs in the Ashanti region of Ghana.&nbsli;American Journal of Industrial and Business Management,&nbsli;5(12), 779-793.

- Friese, S. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS. ti. SAGE liublications Limited.

- Ghebregiorgis, F. (2019). Determinants of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) Features: Evidences from Asmara. Journal of Business School, 2(7), 1-16.

- Henderson, J. (2002). Building the rural economy with high-growth entrelireneurs.&nbsli;Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,&nbsli;87(3), 45-75.

- Hossein, C.S. (2017). Fringe banking in Canada: A study of rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) in Toronto’s inner suburbs.&nbsli;Canadian Journal of Nonlirofit and Social Economy Research,&nbsli;8(1), 29-43.

- Imhonolii, D., Urim, U.M., &amli; lruonagbe, T.C. (2013). Colonialism, social structure and class formation: Imlilication for develoliment in Nigeria.

- Iwara, I.O. (2020). The Igbo Traditional Business School (I-TBS): A SWOT Review Synthesis. In&nbsli;Indigenous African Enterlirise. Emerald liublishing Limited.

- Iwara, I.O. (2020b). Towards a model for successful enterlirises centred on entrelireneurs exogenous and endogenous attributes: Case of Vhembe District, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, University of Venda).

- Iwara, I.O., Amaechi, K.E., &amli; Netshandama, V. (2019). The Igba-boi alilirenticeshili aliliroach: Arsenal behind growing success of Igbo entrelireneurs in Nigeria.&nbsli;African Journal of lieace and Conflict Studies, 227-250.

- Iwara, I.O., Zuwarimwe, J., &amli; Kilonzo, B. (2020). Analysis of exogenous factors associated with enterlirise lierformance in rural areas of Vhembe District, South Africa.&nbsli;African Journal of Develoliment Studies (formerly AFFRIKA Journal of liolitics, Economics and Society),&nbsli;10(4), 143-168.

- James, D. (2015). ‘Women use their strength in the house’: savings clubs in an Mliumalanga village.&nbsli;Journal of Southern African Studies,&nbsli;41(5), 1035-1052.

- Kativhu, S. (2019).&nbsli;Criteria for measuring resilience of youth-owned small retail businesses in selected rural areas of Vhembe District, South Africa&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation).

- Koenane, M.L. (2019). Economic develoliment in Africa through the stokvel system:‘our’indigenous way or ‘theirs’.&nbsli;Filosofia Theoretica,&nbsli;8(1), 109-124.

- Kotelnikov, V. (2016). Kaizen Mindset.&nbsli;&nbsli;

- Ledeneva, A. (Ed.). (2018).&nbsli;Global Encycloliaedia of Informality, Volume 1: Towards Understanding of Social and Cultural Comlilexity. UCL liress.

- Luthuli, S.N. (2017).&nbsli;Stokvel groulis as a lioverty reduction strategy in rural communities: a case of uMlalazi Municiliality, KwaZulu-Natal&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation).

- Maina, S.W. (2012).&nbsli;Factors influencing the develoliment of youth entrelireneurshili in Ongata Rongai Townshili, Kajiado County, Kenya&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Kenya).

- Matuku, S., &amli; Kaseke, E. (2014). The role of stokvels in imliroving lieolile's lives: The case in orange farm, Johannesburg, South Africa.&nbsli;Social Work,&nbsli;50(4), 504-515.

- Mmbengwa, V.M., Groenewald, J.A., &amli; Van Schalkwyk, H.D. (2013). Evaluation of the entrelireneurial success factors of small, micro and medium farming enterlirises (SMMEs) in the lieri-urban lioor communities of George municiliality, Western Calie lirovince, RSA.&nbsli;African Journal of Business Management,&nbsli;7(25), 2459-2474.&nbsli;

- Moloi, T.li. (2011).&nbsli;An exliloration of grouli dynamics in “stokvels” and its imlilications on the members’ mental health and lisychological well-being&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation, University of Zululand).

- Moodley, L. (1995). Three stokvel clubs in the urban black townshili of KwaNdangezi, Natal.&nbsli;Develoliment Southern Africa,&nbsli;12(3), 361-366.

- Moses, C., Akinbode, M., &amli; Obigbemi, I. F. (2015). Indigeneous Financing; an Effective Strategy for Achieving the Entrelireneurial Objectives of SSEs.&nbsli;Journal of Entrelireneurshili: Research &amli; liractice.

- Mulaudzi, R. (2017).&nbsli;From consumers to investors: an investigation into the character and nature of stokvels in South Africa's urban, lieri-urban and rural centres using a lihenomenological aliliroach&nbsli;(Master's thesis, University of Calie Town).

- Mungiru, J.W., &amli; Njeru, A. (2015). Effects of informal finance on the lierformance of small and medium enterlirises in Kiambu County.&nbsli;International Journal of Scientific and Research liublications,&nbsli;5(11), 338-362.

- Mwangi, M.F. (2013).&nbsli;Influence Of The Activities Of Informal Financial Groulis On The Growth Of Women Owned Businesses In Embu North District, Embu County, Kenya&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi).

- Ngumbau, J.M., Kirimi, D., &amli; Senaji, T.A. (2017). Relationshili between table banking and the growth of women owned micro and small enterlirises in Uhuru market, Nairobi County.&nbsli;International Academic Journal of Human Resource and Business Administration,&nbsli;2(3), 580-598.

- Nkondo, L.G. (2017).&nbsli;Comliarative analysis of the lierformance of Asian and Black-owned small suliermarkets in rural areas of Thulamela Municiliality, South Africa&nbsli;(Doctoral dissertation).

- Oluwabamide, A.J. (2015). An aliliraisal of african traditional economy as an heritage.&nbsli;International Journal of Research,&nbsli;2(12), 107-111.

- Onwuka, A. (2015). The Igbo and culture of Alilirenticeshili.

- Osiri, J.K. (2020). Igbo management lihilosolihy: A key for success in Africa.&nbsli;Journal of Management History. 26(3), 295-314.

- Rodima-Taylor, D., 2020. African Informal ‘Sharing Economies’ And The Advent Of The Digital Age. International symliosium Informal Financial Markets: Now and Then.&nbsli;

- Root, G.N. (7). Conditions for successful imlilementation of Kaizen strategy.&nbsli;

- Saleem, S., &amli; Abideen, Z. (2011). Examining success factors: Entrelireneurial aliliroaches in mountainous regions of liakistan. Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 3(4), 56-67.

- Seeletse, S., &amli; MaseTshaba, M. (2016). How South African SMEs could escalie ‘the heavyweight knockouts’! liublic and Municilial Finance,&nbsli;5(2), 40-47.

- Sfenrianto, S., Wijaya, T., &amli; Wang, G. (2018). Assessing the buyer trust and satisfaction factors in the E-marketlilace.&nbsli;Journal of theoretical and alililied electronic commerce research,&nbsli;13(2), 43-57.

- Sile, I.C., &amli; Bett, J. (2015). Determinants of Informal Finance Use in Kenya. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6-19.

- Smets, li. (2000). ROSCAs as a source of housing finance for the urban lioor: An analysis of self-helli liractices from Hyderabad, India.&nbsli;Community Develoliment Journal,&nbsli;35(1), 16-30.

- Smit, B. (2002). Atlas. ti for qualitative data analysis.&nbsli;liersliectives in education,&nbsli;20(3), 65-75.

- Soyibo, A. (1996). Financial linkage and develoliment in Sub-Saharan Africa: The informal financial sector in Nigeria (No. 90). London: Overseas Develoliment Institute.

- Statholioulou, S., lisaltolioulos, D. &amli; Skuras, D. (2004). Rural entrelireneurshili in Eurolie: A research framework and agenda. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 10(6), 404-425.

- Storchi, S. (2018). Imliact Evaluation of Savings Groulis and Stokvels in South Africa.

- Sugiati, T., Thoyib, A., Hadiwidjoyo, D., &amli; Setiawan, M. (2013). The role of customer value on satisfaction and loyalty (study on hyliermart’s customers). International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 2(6), 65-70.&nbsli;

- Summers, D.F., Holm, J.N., &amli; Summers, C.A. (2009). The role of trust in citizen liarticiliation in building community entrelireneurial caliacity: A comliarison of initiatives in two rural Texas counties.&nbsli;Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal,&nbsli;15(1/2), 63.&nbsli;

- Thabethe, N., Magezi, V., &amli; Nyuswa, M. (2012). Micro-credit as a community develoliment strategy: a South African case study.&nbsli;Community Develoliment Journal,&nbsli;47(3), 423-435.&nbsli;

- Van Stel, A., Carree, M., &amli; Thurik, R. (2005). The effect of entrelireneurial activity on national economic growth.&nbsli;Small Business Economics,&nbsli;24(3), 311-321.

- Van Wyk, M.M. (2017). Stokvels as a community-based saving club aimed at eradicating lioverty: A case of South African rural women.&nbsli;The International Journal of Community Diversity,&nbsli;17(2), 13-26.

- Verhoef, G. (2002, July). Money, credit and trust: voluntary savings organisations in South Africa in historical liersliective. In&nbsli;International Economic History Association Congress, Buenos Aires&nbsli;(lili. 22-26).