Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 5

Structural equation modeling of commitment in the COVID-19 era

Elias Alexander Vallejo Montoya, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Cruz Garcia Lirios, Autonomous University of the State of Mexico

Diego Leon Restrepo Lopez, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Hector Enrique Urzola Berrio, University of Antonio José de Sucre Corporation

Clara Judith Brito Carrillo, University of La Guajira

Citation Information: Montoya, E.A.V., Lirios, C.G., Lopez, D.L.R., Berrio, H.E.U., & Carrillo, C.J.B. (2022). Structural Equation Modeling of Commitment In The Covid-19 Era. Journal of International Business Research, 21(5), 1-11.

Abstract

Given that Social Work is immersed in public policies and social programs that are aimed at vulnerable, marginalized or excluded groups, it is necessary to analyze its commitment considering its relationship with management for the treatment of diseases and rehabilitation in institutions of the health sector. In this sense, the objective of this study was to establish the reliability and validity of an instrument that measures work commitment (22 items out of a total of 35) in the health sector. For this purpose, a non-probabilistic sample of 125 social work professionals with experience in the implementation of social programs and monitoring of institutional strategies for health promotion was used. Normality (kurtosis=7.272), reliability (alpha=0.673) and validity (KMO=0.875; X2=12.156; 11gl; p=0.000) of the scale that measured work commitment were established. A reflective structural model was established in which commitment to the institution was positively related to work commitment (β=0.91). The fit and residual indices corroborated the multidimensionality hypothesis of work commitment (GFI=0.975; NFI=0.975, CFI=0.985, RMSEA=0.009). In light of the findings put forward, the scope and limits of the study were discussed.

Keywords

COVID-19, Commitment, Public Policies, Health Sector, Social Work

Introduction

In Mexico, social policies and programs involve assistance to vulnerable, marginalized or excluded groups through the professional practice of Social Work. In the area of health, management and promotion are areas of intervention of Social Work. In other words, as the State encourages human development in its spheres of health, education and employment, it affects institutional strategies for the prevention and treatment of diseases. However, the politicalinstitutional machinery of the health sector requires talents committed to low-income social groups, since networks for local development will be formed among them (Barranco et al., 2010). Therefore, it is relevant to study the indicators of work commitment in professionals linked to social assistance programs. A diagnosis of the areas of opportunity and the virtues of the health management and promotion system will allow us to discuss the emergence of new paradigms of social assistance focused on the promoters of human development (Melano, 2007).

Despite the fact that public institutions are circumscribed to a National Development Plan, the professional practice of Social Work is often conditioned by local or institutional situations or by the work environment, the salary or the stress that personalized attention implies (Ocampo, 2008). In this sense, it is necessary to establish the dimensions of the organizational commitment of Social Work professionals, since a high degree of commitment suggests an efficient level of care which could translate into a favorable evaluation of social policies and institutional programs.

In the case of the health sector, labor commitment, being associated with health management and promotion, is configured by indicators that are responsible for exalting institutional structures and policies to predict personal actions (Ruiz, 2010). In this sense, work commitment has been a transmitter of relationships and conflicts within an institution that inhibit or enhance job satisfaction. As the professional commitment transfers organizational values of collaborative interrelation, it affects the expectations of the members of an organization (Santarsiero, 2012). Such a process supposes the coexistence between indicators of labor commitment that by their nature are complementary and opposite. That is to say, the organizational commitment contains two socialization processes, primary allusive to principles that place the individual in a context and secondary relative to principles that identify him in a structure of power relations, both can be complementary or opposed.

In the field of Social Work, institutions serve as secondary socialization structures to influence the perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, decisions and actions of their employees. In principle, the institutions are a scenario of political rationality in which the State wields social assistance programs that Social Work professionals must follow and in any case perfect said system to achieve a favorable evaluation of public policies and social programs. Such a process of political rationality can be complementary or antagonistic to the principles that guide personal, interpersonal, family or collaborative commitment in the employees of a public institution. In this sense, the commitment derived from primary socialization can come to oppose the organizational commitment derived from second-order socialization.

The psychology of organizations has argued that production processes are inherent to the cognitive processes of those who work in an organization (Rios et al., 2010). In reference to organizational development, organizational psychological studies have shown that commitment is a factor of systematization of production. In this sense, the commitment is assumed as a set of actions, roles, motives and expectations that generate a collaborative dynamic among the members of a work group or productive organization. The organizational commitment model of Caykoylu et al. (2011) proposes seven causes related to empowerment, motivation, identity, trust, ambiguity and conflict, which affect commitment through satisfaction.

An increase in empowerment and motivation would lead to an increase in satisfaction and commitment. However, the reduction of ambiguity and conflict, as they are negatively related to satisfaction, lead to an increase in commitment. Rather, increasing identity and trust also influence satisfaction and commitment (Garcia et al., 2014). If organizational commitment is determined by empowerment, motivation, identity, trust, ambiguity and conflict through satisfaction, then commitment can be defined as the result of the interrelation between organizational factors of a human nature in reference to the relationship between leaders. and employees. In this sense, commitment is a function of personal desires and organizational visions. It is an indicator of fairness and justice in which leaders relate to employees based on a balance between freedoms, capacities and responsibilities.

Within the framework of Higher Education Institutions (IES), commitment is considered an intrinsic value of the individual. In contrast, organization theories posit that commitment is a complex process of interrelationships between psychological and organizational factors aimed at systematizing strategies to achieve goals (Sanchez et al., 2018). The state of the art considers commitment as an intermediate factor between climate and job satisfaction. As organizations systematize production, they substantially increase subjective well-being.

Based on such assumptions, organizational psychologists have assumed that commitment is a product rather than a permanent process of identity (Garcia, 2021). Those who assume a commitment to their companies are considered as a product of organizational dynamics rather than as individuals with collaborative personalities and values. In this sense, the recruitment and selection of prospects is not carried out based on their individual characteristics, but on their abilities and coping strategies in the face of the emergence of conflicts, risk and uncertainty.

Organizational commitment opens the discussion about the relationship between organization and individual. The influence of the first on the second seems to be corroborated by organizational psychological studies, but the commitment, as systematization of functions and results, goes beyond the individual and the organization (Ruiz et al., 2010). Work commitment refers to a set of moral and evaluative principles characteristic of leaders who, in their eagerness to achieve goals, firmly believe in the ideals of productivity, order and systematization of organizational functions.

In short, commitment is a set of beliefs, attitudes and actions that reduce uncertainty and increase propensity for the future. The increase in risk expectations would decrease motivation for work and would disorder the human relations system, affecting the performance of each member. Psychological studies of work commitment have established causal relationships between this variable and leadership styles (Anwar & Norulkamar, 2012). As the type of leadership intensifies, it explains the increase in work commitment. That is, the different types of leadership affect the increase or decrease of the perceptions, attitudes, decisions and actions of the employees. In this sense, the history of performance affects the commitment to increase productivity in the future (Tayo & Adeyemi, 2012). That is, behind work commitment, command structures, task relationships, conflicts and stress or satisfaction seem to explain the increase or decrease in commitment assumed by employees during their work stay, although for Manas et al. (2007) sex and for Mendoza et al. (2010) customer service explain the degree of work commitment.

Manas et al. (2007) as well as Anwar & Norulkamar (2012) agree in relating life satisfaction with commitment. Such findings suppose continuity between primary and secondary socialization, whether in a collectivist or individualistic, favorable or unfavorable sense, the principles that guide the individual in a family group would be the same that guide them in a work or productive group. In light of these results, work commitment would be the last link, at least in the workplace, in a chain of perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, decisions and actions directed from the primary group in which the individual learned the basic symbols and in whose development he never had the opportunity to question such principles that now seem to guide him in his commitment, productivity and job satisfaction. In short, the state of the art seems to show solid evidence regarding the complementarity between primary socialization and secondary socialization.

Therefore, it is necessary to clarify the dimensions of organizational commitment based on the complexity involved in the practice of Social Work. This study seeks to establish the dimensions of work commitment considering levels of institutional complexity that would frame the disagreement with indicators of a commitment derived from primary socialization.

What are the dimensions of labor commitment in Social Work professionals who work in public institutions, but have had a critical training around the exercise of their profession and have been socialized under collectivist principles where the interests of the majority prevail over the objectives? Personal or institutional.

To answer the question, the Theory of Labor Commitment was reviewed, which together with organizational psychological studies show that: Work commitment, as a framework of perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, intentions and actions, is configured by various dimensions since individual, group and institutional values converge in it. Work commitment, despite its configuration, is one-dimensional when adjusting personal expectations and group values to organizational structure and politics.

Method

Design

A cross-sectional study (only a diagnosis is made in a given time and space) and a correlational study (only associative relationships between ordinal variables are established) were carried out (Garcia Lirios, 2021a&b).

Sample

Non-probabilistic selection of 125 professionals (75 women and 50 men with an average age of 33 years and 7 having graduated) from Social Work at health centers in the state of Morelos (Mexico) with an average monthly income of 870 USD (SD=12.5 USD) and seven years of work experience (SD=2.3). Considering that the organizational commitment is influenced by social policy and the assistance program, knowing the National and Institutional Development Plan as well as the areas of professional practice was considered convenient as an inclusion criterion (Garcia Lirios et al., 2014).

Instrument

Questions related to gender, age, income, origin, experience, and marital and family status were included. The Garcia-Lirios Labor Commitment Scale (2011) was used, which includes reagents around perceptions of support (4 items), recognition (12 items), learning (11 items) and job evaluation (8 items). Each item includes five response options ranging from “never” to “always” Table 1 (Garcia Lirios et al., 2019).

| Table 1 Operationalization Of Factors |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Definition | Example item | Weighing | Measurement | Items |

| Institutional support | It refers to the perception of the facilities granted by the leaders of the institution to carry out the professional practice in reference to social policy and institutional programs. | “The health center has the resources that social policy needs to help people” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 1,2,3,4,5 |

| supraordinal recognition | The set of perceptions that employees have regarding the achievements that are enunciated by their leaders as extraordinary actions. | “Our leader is very given to praising those who visit distant communities” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 |

| Healthcare assessment | They are perceptions related to the relevance of the professional practice that is carried out considering the supervision of leaders (Garcia et al., 2019). | “Microcredit to single mothers impacts indigenous communities” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 14,15,16,17,18 |

| Collaborative learning | It refers to perceptions of shared professional practices that were previously carried out discretionally (Sanchez-Sanchez et al., 2018). | “Before I could visit more communities because I didn't have to check a card” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 19,20,21 |

| personal recognition | They are perceptions about one's own professional practice in reference to the comments of leaders (Garcia, 2021) | “I like my work when I deliver groceries to people” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 22,23,24,25,26, |

| family recognition | They are perceptions related to achievements that, when highlighted by family members, guide professional practice towards an emotional order. | “My family tells me that I help people who look crushed” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 27,28,29 |

| functional learning | They are perceptions about challenges and opportunities in reference to the professional practice that the leaders of the institution have implemented as internal norms (Sanchez et al., 2019). | “Our boss tells us that we must get involved with the indigenous communities” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 30,31,32 |

| interpersonal assessment | It refers to perceptions alluding to the social relevance of professional practice in relation to comments from colleagues, friends or partners. | “My colleagues are willing to go to places of extreme poverty” | Measurement of perceptions from frequencies ranging from never to always | Ordinal | 33,34,35 |

Procedure

Respondents express their degree of commitment regarding specific situations of their job functions and their organizational environment. Through a telephone contact with the selected sample in which they were asked for an interview and whose purposes would be merely academic and institutional to monitor the graduates, whether they were graduates or not. Once the appointment was established, they were given a questionnaire that included sociodemographic, economic, and psych organizational questions. In the cases in which there was a tendency to the same answer option or, alternatively, the absence of a response, they were asked to write down on the back the reasons why they answered with the same answer option or, where appropriate, the absence of them. The data was captured in the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) and the analyses of structural equations were estimated with the help of the Analysis of Structural Moments (AMOS) program and the Relationships program. Linear Structural (LISREL).

Analysis

The establishment of the structural model of reflective relationships between work commitment and its indicators was carried out considering the normality, reliability and validity of the scale that measured the psychological construct. Table 2 shows the results of the normality, reliability and validity analyses. The kurtosis parameter was used to establish the normality of the distribution of responses to the level of commitment questioned. The results show that the kurtosis parameter had a value lower than eight, which is the minimum suggested to assume normality of distribution. In the case of reliability, Cronbach's alpha value allowed establishing the relationship between each question and the scale. The value greater than 0.60 was considered as evidence of internal consistency. Finally, the exploratory factorial analysis of principal components and varimax rotation in which factorial weights greater than 0.300 allowed deducing the emergence of commitment from eight indicators.

| Table 2 Normal Distribution, Factor Analysis And Reliability Of Organizational Commitment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Half | Deviation | Bias | kurtosis | Factor Weight |

| Institutional | 3.1 | 0.24 | -1,378 | 0.985 | 0.304 |

| Supraorbital | 2.1 | 0.12 | -1,194 | 0.548 | -.385 |

| Assistance | 2.5 | 0.25 | 1,878 | 2,981 | 0.465 |

| collaborative | 2.6 | 0.13 | 1,280 | 0.446 | 0.305 |

| Staff | 2.0 | 0.15 | 1,362 | 0,887 | -.567 |

| Family | 1.7 | 0.17 | 2,152 | 3,761 | 0.687 |

| Functional | 3.5 | 0.10 | 2,043 | 3,746 | -.342 |

| interpersonal | 4.6 | 0.3.4 | -.885 | -.333 | 0.723 |

Multivariate=7.272; Bootstrap=0.000; Alpha =0.673; KMO =0.875; X2 = 12,156; 11gl; _ p=0.000

Once normality, reliability and validity were established, the covariances between the indicators were established to model the existing relationships with the organizational factor.

Results

The analysis of covariances shows negative and positive, significant and spurious associations between the indicators of work commitment Table 3. In the case of the commitment that the surveyed sample has with the institution where they work, it is related to the commitment to growth as a couple (Φ=0.901). In other words, as the institutional objectives are met, they seem to affect the objectives shared with a couple. In this sense, interpersonal dynamics could be interrelated with other collaborative dynamics that in the workplace are inherent to the task climate or the relationship climate (Medina et al., 2004).

| Table 3 Covariances Between The Determinants Of Organizational Commitment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional | Supraordinal | Assistance | collaborative | Staff | Family | Functional | interpersonal | |

| Institutional | 0.072 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Supraordinal | 0.710 | 0.594 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Assistance | -0.586 | -0.434 | 0.042 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Collaborative | -0.388 | -0.038 | 0.035 | 0.210 | - | - | - | - |

| Staff | -0. 635 | -0.009 | 0.187 | 0.055 | 0.103 | - | - | |

| Family | -0.188 | -0.375 | 0.628 | 0.725 | 0.652 | 0.677 | - | - |

| Functional | -0.224 | -0.230 | 0.388 | 0.198 | 0.704 | 0.205 | 0.195 | - |

| interpersonal | 0.901 | 0.650 | -0.160 | -0.200 | -0.776 | -0. 528 | 0.170 | 0.592 |

In contrast, commitment to oneself, which reflects a propensity for individualism in reference to institutional commitment, which implies a propensity for collectivism, are opposite indicators since while the values of a variable increase, a decrease is observed in the values of the other variable (Φ=-0.635). This is that personal purposes do not seem to converge with the interests of the institution where Social Work professionals perform their functions. Supraordinal indicator, which denotes a commitment beyond the simple functions of observation, interview, systematization, and intervention that the profession requires, the criticism of these functions is linked to interpersonal objectives (Φ=0.650). In this sense, the climate of tasks and the climate of relationships are closer to the critical commitment of the profession than to conflict, since the questioning of welfare functions is necessary in the development of Social Work (Mojoyinola, 2006). Perhaps it is for this reason that criticism of the profession maintained a negative relationship with commitment to care (Φ=-0.434).

On the other hand, the care commitment had its greatest link with the family commitment (Φ=0.628). Both indicators maintained positive relationships from which it is possible to deduce that the surveyed sample shows a close relationship between the exercise of the profession as a care commitment and the type of group to which they belong or want to belong. This is a third socialization of the social work professional in which public policies and assistance programs seem to complement the secondary socialization of the families and groups that surrounded the Social Work professionals in their development.

On the contrary, welfare commitment is negatively related to interpersonal commitment (Φ=-0.160). Although the relationship is spurious, other variables exert influence on both commitments; such an association is relevant since the commitment to the institution that projects and directs the social programs vanishes before the interrelation of the Social Work professional with other colleagues, groups vulnerable, reference or belonging. Commitment to the closest interpersonal circle is opposed to institutional politics

In the case of the relationship between collaborative commitment and family commitment (Φ=0.725), it is possible to observe that the primary socialization group acts as a complement to the secondary socialization group. In systemic terms, the mesosystem in which family and work are indicators par excellence can be explained from commitment as a multidimensional factor (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Brofenbrenner, 1994). However, collaborative engagement is negatively related to interpersonal engagement (Φ=-0.200).

On the other hand, commitment to oneself is positively associated with commitment to the profession: social work (Φ=0.704). Personal and work identities, being linked, explain the consistent exercise of the profession even despite its vicissitudes. In a context in which the functions of Social Work are reduced to technical procedures and risk inherent in socioeconomic studies, Social Work professionals show a close association between the functions of their work and personal life goals, but such aspects are overshadowed by relationships with their fellow professionals since commitment to the profession is opposed to interpersonal commitment (Φ=- 0.776).

worth highlighting the association between institutional and supraorbital commitment (Φ=0.710), which supposes that the norms of health centers and the recognition of managers towards the professional practice of social workers are associated in such a way that the granting of resources, socioeconomic studies or home visits seem to be linked to the organizational structure in terms of the distribution of resources or microcredits.

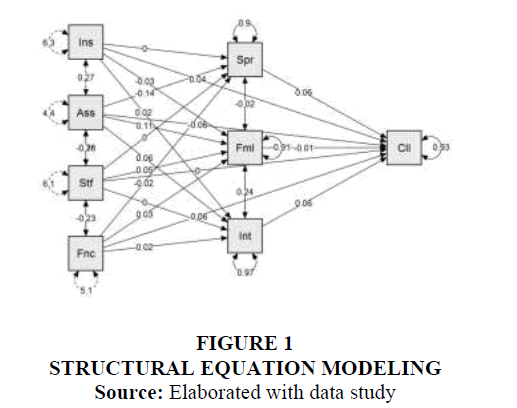

In the case of personal commitment and that derived from family recognition (Φ=0.652), the relationship suggests an interlocution between the information that family members have about Social Work and its professional practice. This finding is relevant in light of the Caykoylu et al. (2011) since it confirms the hypothesis that commitment is the result of organizational factors in reference to personal desires. Once the covariances between the indicators were established, a reflective model was estimated. Figure 1 shows a higher correlation between workorganizational commitment and the institutional indicator (β=0.91). In this sense, the psychological construct of labor-organizational commitment is explained by commitment to institutional politics. Apparently, Social Work professionals are influenced by organizational principles rather than by personal, interpersonal, collaborative, functional, professional, caregiving, family, or critical goals inherent in Social Work. In an opposite sense, the critical commitment of the profession was negatively related to the factor (β=-0.42). Such a result complements the assumption around which Social Work professionals adjust their objectives to the internal policies of the institution for which they work, although they coexist with other principles that guide organizational commitment.

Finally, the adjustment and residual indices were estimated to test the hypothesis regarding the configuration of an organizational commitment that would have as indicators aspects inherent to the individual, family, colleagues, functions, policies and structure in which each social worker is inserted Table 4.

| Table 4 Adjustment Indices Of The Organizational Commitment Structure |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi Square | Degrees of freedom | Significance Level | Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | Normal Fit Index (NFI) | Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) |

| 17.00 | .13 | .000 | .975 | .975 | .985 | .009 |

The results show that the null hypothesis can be accepted since the fit indices are close to unity and the residual close to zero.

Discussion

The present study has established eight dimensions of organizational commitment to show the differences between the commitment derived from a primary socialization that was observed in the personal, interpersonal, family and collaborative objectives compared to the commitment derived from a secondary socialization that was observed in the principles. Assistance, functional institutional and supraorbital. The convergence between these principles of contextual location and identity in the face of power relations allows us to deduce that work commitment is a network of perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, decisions and actions aimed at the interrelation between the eight dimensions mentioned.

However, the prevalence of institutional commitment seems to show that Social Work professionals adjust their objectives to the structure and politics of the organization for which they work. Such findings are relevant in light of the Labor Commitment Theory since they complement one of its principles related to customer service. To the extent that organizations follow a service quality evaluation and satisfaction policy, they foster an increase in the responsibilities, expectations and commitments of their employees (Caykoylu et al., 2011). In this way, the present study has found that the adjustment to the norms and policies of an organization prevails over personal, interpersonal, collaborative and family objectives. That is, if service quality policies were followed in the institutions where Social Work professionals work and productivity was established based on consecutive evaluations, the surveyed sample would adjust its primary commitments to the objectives of said institution.

However, the command structure, according to the studies by Anwar & Norulkamar (2012), Tayo & Adeyemi (2012), show that the leadership style explains a higher percentage of the variance of work commitment in reference to job satisfaction. Life, performance or productivity. In this sense, the present investigation maintains that the commitment to the institution, coexisting with the personal commitment, explains the influence of the leadership style. In the context of the study, the sample surveyed expressed a work commitment consisting of matching their expectations with the mission and vision of the institution where they work. Therefore, it is logical to think that the leadership style complements the primary socialization.

Despite the contributions put forward, it is recommended to extend the study to leadership styles in order to develop a theory to explain the influence of the institutional power structure on the work commitment of Social Work professionals. If it is considered that leadership in institutions is occupied by other health professionals such as administrators, accountants or doctors, then it would be pertinent to explain the areas of opportunity for Social Work professionals when assuming a greater commitment and responsibility: planning of an institution.

Now, regarding the construction of an explanatory model of job satisfaction as an indicator of efficiency in the professional practice of Social Work, it is necessary to consider the incidence of social programs and sectorial strategies since the dynamics of evaluation of social and institutional policies It supposes the achievement of objectives by a human capital willing to reproduce the development plans on social needs as well as manage the opportunities and capacities to spread responsibilities such as health in vulnerable, marginalized or excluded sectors. The success of development policies is centered on the level of commitment of those who carry out institutional plans and strategies manage resources and promote a culture of selfcare, without whom any development plan would be fallible.

Conclusion

The objective and contribution of this work to the state of the question was to compare the theoretical structure reported in the literature with respect to the observations made in this study. The results show that the factors are related to each other with a scope for labor commitment. The literature suggests that this variable is multidimensional and the results support it. The structural composition of work commitment suggests eight preponderant dimensions. These same components were established in the present study, although their relationships are close to zero. The areas and lines of research concerning the eight components and their structural relationships will allow us to notice the impact of the pandemic on work commitment. If the studies suggest that there is a configuration of eight components reflecting commitment, and the results of the study note that structure in a formative way, then the discussion should focus on the setting of the agenda before and after the pandemic and how it modified the agenda reported engagement structure.

References

Anwar, F. & Norulkamar, U. (2012). Mediating role of organizational commitment among leaders' chip and employee outcomes, and empirical evidence from telecom sector. Processing International Seminar on Industrial Engineering and Management 2, 116-161.

Barranco, C., Delgado, M., Melin, C., & Quintana, R. (2010). Social work in housing: research on perceived quality of life. Portularia, 10, 101-111.

Brofenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development.International encyclopedia of education,3(2), 1643-1647.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Towards an experimental ecology of human development. American psychologist. 32, 523-530.

Caykoylu, S., Egri, C., Havlovic, S. & Bradley, C. (2011). Key organizational commitment antecedents for nurses, paramedical professionals and non-clinical staff. Journal of Health Organization and Management. 25, 7-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Garcia Lirios, C. (2021a). Modeling of work commitment in the face of COVID-19 in a public hospital in central Mexico. Bolivian Medical Gazette, 44(1), 34-39.

Garcia Lirios, C. (2021b). Occupational risk perceptions in the Post Covid-19 era. Know and Share Psychology, 2(1).

Garcia Lirios, C., Carreón Guillén, J., Hernández Valdés, J., & Morales Flores, M. de L. (2014). Contrast of a model of work commitment in public health centers. University Act, 24(1), 48–59.

Garcia Lirios, C., Carreón Guillén, J., Rincón Ornelas, R.M., Bolivar Mojica, E., Sanchez Sánchez, A., & Bermudez Ruiz, G. (2019). Contrast of a knowledge management model in a public university in central Mexico. 360: Journal of Management Sciences, (4), 105-127.

Manas, M.A., Salvador, C., Boada, J., González, E., & Agulló, E. (2007). Satisfaction and psychological well-being as antecedentsoforganisationalcommitment.Psicothema,19(3), 395-400.

Medina, F., Munduate, L., Martínez, I., Dorado, M., & Mañas, M. (2004). Positive effects of the activation of task conflict on the climate of work teams. Journal of Social Psychology. 10, 3-15.

Melano., M. (2007). Citizenship and autonomy in Social Work: the role of political and technical scientific knowledge. Alternatives Magazine, 15, 99-110.

Mendoza, M., Orgambídez, A., & Carrasco, A. (2010). Orientation of total quality, job satisfaction, communication and commitment in rural tourism establishments. Magazine of Tourism and Cultural Heritage. 8, 351-361.

Mojoyinola, J. (2006). Social work interventions in the prevention and management of domestic violence. Journal of Social Science. 13, 97-99.

Ocampo, J. (2008). The conceptions of social policy: universalism versus targeting. New Society, 215, 36-61.

Ruiz, HDM, Munoz, EM, Aguayo, JMB, Nájera, MJ, & Lirios, CG (2020).Peri-Urban Socio-Environmental Representations.Kuxulkab',26(54), 05-12.

Ruiz, L. (2010). Urban security management: criminal policy and municipalities. Journal of Criminal Science and Criminology, 12, 1-125

Sanchez, A., Vales-Ambrosio, O., Garcia-Lirios, C., & Amemiya-Ramirez, M. (2019). Reliability and validity of an instrument that measures knowledge management. BLANKS. Education Magazine (Inquiries Series), 1(30), 9-22.

Sanchez, A.S., Guillen, J.C., Ruiz, H.D.M., & Lirios, C.G. (2018). Contracting a model of labor training. Interconnecting knowledge, (5), 37-73.

Sanchez-Sanchez, A., Aguayo, JMB., Vades, JH., Guillen, JC., Munoz, EM., & Lirios, CG. (2018). Factorial structure of the determinants of organizational bullying. Hispanic American Notebooks of Psychology, 18 (1).

Santarsiero., L. (2012). Social policies in the case of satisfaction of needs. Some conceptual elements for its determination. Work and Society, 18, 159-176.

Tayo, E., & Adeyemi, A. (2012). Job involvement & organizational commitment as determinants of job performance among educational resource centre personal.European Journal of Globalization and Development Research,5(1), 302-311.

Received: 02-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. JIBR-22-12613; Editor assigned: 05-Sep-2022, Pre QC No. JIBR-22-12613(PQ); Reviewed: 19- Sep-2022, QC No. JIBR-22-12613; Revised: 26-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. JIBR-22-12613(R); Published: 30-Sep-2022