Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 1

Taxation of International Business Organizations

Najim Abd Aliwie Al Karaawy, College of Administration and Economics, University of Qadisiya

Qassim Mohammed Abdullah Al Baaj, College of Administration and Economics, University of Qadisiya

Keywords

International Business Organizations, High-Tax Jurisdiction, Low-Tax Jurisdiction, Tax Avoidance, Tax Evasion.

Highlights

1. Congress has in the past addressed tax circumvention and avoidance by using tax refuges;

2. International companies can transfer proceeds from high-tax to low-tax territories;

3. Persons can dodge tax on passive income;

4. Changing tax law is essential for addressing profit movement by international firms.

Introduction

All nations around the world evaluate taxation on business organizations using varying tax systems, rates, compliance requirements and incentive provisions. Different countries evaluate tax on the domestic corporations and its citizens not considering where they earn the revenues. Many nations in the globe evaluate similar kinds of taxes as those of the United States like payroll taxes, consumption taxes, value-added taxes (VAT) and so forth. VAT is more dominant in Europe and contributes much of the governments’ total revenues. The approaches of composing taxable income and rates of taxation differ between various countries. The different nations provide for varying methods of depreciation where the straight line approach is more prevalent as compared to the reducing balance method.

In the United States, international business dealings are categorized into two classes. First, there are the outbound transactions in which American nationals and local organizations do business or invest overseas. Second, the inbound transactions involve foreign companies and non-resident alien individuals doing business in the United States. Both of these types of transactions are taxed by the federal government. Without inbound taxation, local business organizations are likely to be disadvantaged as compared to foreign firms doing business in the US in case their foreign taxes are lower as compared to those of America (Barrios, 2012). In totality, taxation is a critical factor to international businesses because investors highly consider it before deciding to invest in a certain region in the world. The article looks into different issues associated with international business taxation. However, the main focal point of the article is international tax avoidance on the multi-national business organizations.

Methods

The paper uses a qualitative approach to research and it uncovers trends in opinions, thought patterns and facts regarding the issue of taxation in International Accounting. Mainly, the article is based on textual analysis from secondary sources; books, journal articles, government publications and Internet sources in particular.

Materials of Research

The article derives facts from a broad range of academic and administrative works in building on the arguments of international taxation. Firstly, there is the use of journal databases in incorporating factual figures and statistics in the paper. The numbers are in support of the thesis statement of the paper and main argument for which the paper advocates. Secondly, there is the use of scholarly articles as reference points when writing down the paper. Articles have advised a significant part of the document. A majority of the articles are academic while others come from administrative quarters and so they are in the public domain. Thirdly, this paper derives information from professional websites in building on the arguments. It has exploited different online sources that are deemed credible for using in academic work. When borrowing information from a website, it has been important to determine its credibility through establishing the authors. The authors’ highest credentials are publicized and are verifiable in a website that is deemed fit for sourcing factual material. Also, credible online sources talk about the publication dates and publishers of the content that they hold. In this sense, it is possible to tell the relevance and validity of the facts that they publish for readers to absorb. Finally, the paper heavily borrows from academic books when applying theoretical knowledge regarding the issue of taxation in the context of international accounting. Books are the most detailed sources of information regarding this topic and for this article in particular.

Searching

When locating source materials, there was the utilization of keywords in a bid to establish and maintain relevance. Other than relying on the limited key terms, it became imperative to use synonyms to access a broad range of potential materials to utilize in creating the paper. Settling on the different sources came after searching for similar terms and ending up with different like-minded scholars’ published works.

Inclusion Criteria

When undertaking the systematic literature review, it was important to develop of criteria of deciding the materials to be used when developing the paper. In the paper, the criteria were basically based on the nature of the research topic; taxation in the light of international accounting. The sources had to be relevant to the subject of international accounting and more so about taxation in the field of evasion and avoidance. For articles, they had to be peer-reviewed in order to ensure that they have accurate and sound information regarding the topic. All the sources used, had to be less than ten years from the time that they were published to ensure relevance of their content.

Ethical Issues

All pieces of research require that the author observes ethical issues not to infringe on intellectual rights of other people’s works. Information from all the sources was obtained lawfully without the duplication of a scholar’s original work. Ideas borrowed from other people’s works are recognized through proper referencing to indicate the source of a given matter of fact. It is ethical that all pieces of information gathered in the process of conducting research are reported accurately in the final document. In this sense, efforts have been put towards ensuring that all the data and theoretical ideas borrowed from other writers’ works are transferred accurately in this final document.

Results

Legal Control of Economic Relationships

Taxation is not only a form of economic regulation; rather it is a dynamic and contradictory process in many ways. International business taxation mainly involves a process of the bargain between corporate bodies and tax officials. The tax system is structured in a hierarchic arrangement and the officials have access to state power. They are capable of ordering an audit, publish regulations, issue an evaluation to tax or go to court or the legislative arm of the government to amend or clarify a certain law (Czinkota et al., 2011).

Recourse to legislative intervention or legal adjudication depends on technical legal issues, interpretation of the statute and a wide range of other factors (Czinkota et al., 2011). They are the cultural elements in the administrative process such as relations and social backgrounds of actors, overall social attitudes and political affiliations. Such factors greatly influence the manner in which taxation of international businesses is carried out. They can encourage tax avoidance at that level and this result in a loss of revenue by the governments. In a bid to avoid such situations, it is important for tax officials and the government at large to put in place instrumental tax planning strategies.

Tax planning offers business enterprises the power of initiative and this means that the tax collector responds to certain events. On the contrary, tax officials have broad powers bestowed on them and this disallows claims that can reverse the advantages by putting the taxpayer in a defensive position. It is not all the taxpayers that want to divert significant resources from their real business tax planning. A system which provides for this malpractice undermines the concept of equity and results in wastage of resources. Regardless of all the social and political issues surrounding an economy, it is upon the tax collecting authorities to make sure that government revenues are not lost as a result of unscrupulous business persons who do not want to pay tax (Doupnik & Perera, 2011). Through reacting to tax prompting events, tax officials are likely to be in a position to seal different loopholes where government revenue is lost. Also, there is the need for a social approach of law that is capable of theorizing the historical progression of regulation forms including certain legal doctrines and their use as social processes.

Tax Havens

Tax havens are characterized by low or zero taxes, the absence of transparency, deficiency of effect interchange of info and lack of need for significant activity. They involve suppressed taxation remittance to tax officials and so there is an incentive offered by the government. Congress created a list of tax havens which aimed at treating organizations incorporated in specific tax havens as domestic businesses. In the 111th Congress, legislation was introduced to curb the abuse of tax havens by dishonest business persons who aimed at defrauding the government. It used a separate list that was obtained from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) court documents but had a majority of nations mutually. The list brought forward by OECD did not include low-tax jurisdictions, with some of them being OECD associates who were deemed by many people as tax havens like Switzerland and Ireland.

The nations absent from the initial list are the developed and larger nations and they are members of OECD such as Luxembourg and Switzerland. It is vital to make a difference between OECD’s initial list and its blacklist. Later, the body looked into information discussion and aloof nations for the ban once they decided to collaborate (Egger, 2010). The reduction of the OECD list was not attributable to real development to teamwork. Rather was because of the intensified focus on evidence on appeal and not calling for reorganizations until all the parties were signed. The breakdown postulates that the large nations were unsuccessful in their quest to harness the tax havens.

In the recent past, interest in tax havens has gone up. There have been major scandals touching the Liechtenstein Global Trust Group (LGT) and Swiss Bank, leading to lawsuits by the United States and other nations. Great focus is now accorded to international business taxation issues mainly data showing individual corporate evasion. The allowance of public funds to banks and the credit crisis has up-surged public interest and concern. The issue of tax havens was recently revived in a summit of the G20 both developing and industrializes nations that suggested sanctions (Gravelle, 2016). Different countries started to signify dedication to information sharing agreements on an international platform.

Methods of International Corporate Tax Avoidance

The United States multinational companies are not overtaxed on revenues received by overseas holdings till they are shifted to the US main firm as disbursements. However, some related and passive organizational revenues that are easily moved are taxed pursuant to the anti-abuse rules and regulations. Taxes on repatriated revenues provide for credit for the overseas income taxation remitted. The overseas taxation credits are constrained to the quantity of taxation enforced by the US so that in theory, they cannot counterbalance tax on local revenue (Griffin, Ricky and Pustay, 88). The limitation is enforced on a general basis, providing for extra credits in the high-tax nations to balance the United States taxation obligation on the revenue gained in the low-tax nations; distinct extents are applicable to both active and passive incomes. Other nations utilize this arrangement of credit or deferment or exempted revenue made in the extraneous nations with a majority of them having anti-abuse rules. If an organization can move proceeds from a high-tax state to a low-tax one, its taxes are lessened without impacting on other facets of the firm. Tax variances also impact on actual commercial activities, in turn affecting revenue levels.

The United States enforces taxes on all revenues gained in its boundaries and imposes residual taxation on proceeds earned by its citizens abroad. For this reason; taxation circumvention relates to both the US main organizations moving proceeds overseas to low-tax countries and moving of incomes beyond the US by alien parents of US subsidiaries. In the case of the United States multinational companies, past research has shown that about 50 percent of the variance between productivity in the low-tax and high-tax jurisdiction is attributable to the allocation of debt and transfers of intellectual property (Karkinsky & Riedel, 2012).

Evidence regarding the significance of scholarly stuff can be located in the sorts of organizations that shifted incomes overseas pursuing an impermanent decrease in taxation ratified in 2004 (Karkinsky & Riedel, 2012). One-third of the shifts were in the medicine and pharmaceutical sector and about 20% in the electronic equipment and computer trade. Taxing American corporate bodies and individual persons based in overseas countries significantly adds to be country’s tax collection base. However, it raises the question of double-taxation where the citizens are taxed both by their home administration and the host governments in the overseas countries. Organizations shift their earnings to the home country in systematically arranged ways as illustrated in this section of the document.

Earnings Stripping and Allocation of Debt

Among the most prevalent methods of moving earnings from high-tax jurisdictions to low-tax ones is to highly acquire funds in the high-tax countries and diminishingly in the low-tax ones. Such moving of liability is accomplished without altering the general debt disclosure of an organization. An additionally certain practice is the earning stripping; the debt is associated unrelated liability or related firms and is not subject to taxation by the receiver (McDaniel, Repetti & Ring, 2014). For example, a main alien company could advance credit to its branch in the United States. Alternatively, a disparate overseas debtor not subject to taxation on the United States interest revenue could advance to an American company.

The United States code of taxation currently has provisions that reflect on interest cuts and proceeds stripping. It applies to the distribution of the United States parent company’s interest for the constraint on overseas taxation credit. The quantity of overseas spring of revenue is suppressed when a section of the US interest is allotted and the extreme amounts of alien company credits are restricted. In this case, there is an assertion that impacts on organizations with excessive overseas taxation credits. There lacks an apportionment regulation to guide deferral so that a US parent company can run its branch with a holistic equity funding in a low-tax country and assume all the interests in the general company’s liability as a cut. Chairman Rangek of the Ways and Means Committee introduced a bill in the year 2007 and it came with a rule of allocation so that a section of interests and other overheads would not be deducted until the income is shifted to the home country (Mintz & Weichenrieder, 2010). The provision was also present in President Obama’s proposal regarding global tax review and other congressional suggestions.

Apportionment of interest approaches was applied in addressing the interest of high-tax nations. In the situation of the United States multinational corporations, they are inapplicable to the American subsidiaries of foreign companies. The United States has thin capitalization regulations so that to provide for the limitation of the scope of earning stripping. A portion of the Internal Revenue Code is applicable to an organization with a debt to equity ratio beyond 1.5 to 1.0 and characterized by rates of interest going beyond 50 percent of the adjusted ratable revenue. Interest above the 50 percent edge remunerated to a correlated organization cannot be deducted if the company is not under the US revenue tax bracket (Picciotto & Mayne, 2016). The same interest limitation is applicable to interest rewarded to distinct entities which are not tax-burdened to recipients.

The probability of proceeds stripping has gained more focus after certain American organizations inverted. The firms organized to shift their main firms overseas to make the US operations become a branch of the main company. The American Job Creation Act of 2004 guided the entire issue of transposal through handling organizations that reversed as American companies. When considering this piece of law, there were different applications for wider proceeds stripping limitations as a methodology to this issue which would potentially have minimized the excessive tax deductions. The universal earnings stripping suggestion was assumed in totality. However, the Treasury Department was authorized to study this and other issues are focusing on the United States subsidiaries of overseas parents and were unable to provide sufficient proof of the magnitude. The Treasury’s investigation looked into this issue and applied a methodology which had been utilized in the past of likening the branches to the American firms (Mintz & Weichenrieder, 2010). The survey did not offer convincing proof about moving of proceeds beyond the United States because of great weight rates for the country’s branches of overseas companies. However, it found concrete evidence of shifting regarding the inverted firms.

In the recent past, inversions have become a major issue. Even if some organizations inverted pursuant to the 2004 bill, on the basis of activity exception, the approach was constrained by regulation. In the year 2014 some American firms inverted through amalgamating with smaller overseas companies (McDaniel, Repetti & Ring, 2014). The president proposed more stringent limitations on the inversions and the two bills concerning the issue were tabled in the 113th Congress. Regulatory alterations to restrict some profits were made.

Transfer Pricing

The second principal avenue through which international businesses shift earnings from high-tax to low-tax nations is by prizing of services and goods traded between the partner countries. In a bid to reflect on income properly, prices of products and services offered by linked organizations are supposed to be similar to those that would be compensated up by disparate parties. Income can be shifted between these authorities through dropping the cost of products and amenities traded by the parent organizations and high-tax jurisdictions as well as inflating the cost of acquisitions. A significant and expanding issue of transfer pricing is the shift of justifications to rational property and intangible goods (Karkinsky & Riedel, 2012). If a manifest established in the United States is authorized to a partner in a low-tax jurisdiction, revenue is moved if the payment or other expenditures are below the true worth of the authorization. For numerous products, similar goods that are offered or other approaches that are applied in establishing if charges are set properly. Intangible property like new drugs or fresh inventions are not comparable and it is hard to establish the payments that could be waged up at an arms-length cost. For this reason; intangible is a representation of certain issues for monitoring the concept of transferal pricing.

Investments in intangible properties are handled positively in the United States since prices except for buildings and capital goods are incurred for R&D purposes and this also qualifies for taxation credit. Additionally, publicizing to build brands is also tax deductible. In general, such actions have the tendency of producing a low, zero or negatives rates of taxation for the overall funds in intangible goods (Karkinsky & Riedel, 2012). Hence, there are substantial benefits of making the reserves in the United States. Standardly, the incentives of tax decrements or credits to advance these investments usually offset taxes in the future on return on investment. However, for the succeeding investments, it is beneficial to move the proceeds to a low-tax dominion in a bid to secure tax reserves on the venture and minimal returns on taxation. For this reason; these hoards are potentially subject to adverse rates of tax and subventions that can be substantial.

Rules and regulations of transfer pricing in accordance with intellectual property are complicated due to the price of sharing agreements where various partners make contributions to the cost. In a situation where an imperceptible asset is partly established by a parent organization, affiliate firms advance contributions towards a buy-in consideration. It is cumbersome to establish arms-length appraising in such situations where there is the partial development of technology and there is a risk connected to the anticipated results. Past research shows that international organizations with cost-sharing agreements have a higher probability of engaging in the concept of profit shifting (Gravelle, 2016). One of the problematic issues with moving profits to certain tax refuge countries is that if realistic activities are essential to offer the intangible assets, such countries may lack sufficient labor and other vital resources that are necessary for conducting the activity. However, organizations have come up with established approaches in a bid to exploit regulations in other nations to accomplish an industrious operation when moving profits to zero-tax nations.

Hybrid Instruments, Hybrid Entities, Check-the-Box

The other approach of moving profits to the low-tax jurisdictions grew highly with the provisions of check-the-box. Initially, the provisions were meant to simplify the issues of whether an organization was a partnership or a corporation. The application of foreign situations through disregarding body regulations has resulted in the growth of hybrid corporates where a firm is acknowledged as a body corporate by a single jurisdiction but not others. For instance, an American parent’s branch in a low-tax nation can advance money to its other subsidiaries in the high-tax nations. It will do so potentially subject to interest reducible since the high-tax jurisdictions see the organization as an independent body. In normal circumstances, interest accrued by a branch in the low-tax nation is deemed passive income which is subject to the current United States tax (Picciotto & Mayne, 2016). From the United States point of view, there lacks interest revenue paid since the two are a single entity. The look-through regulations increase the latitude of check-the-box to more associated entities and situations. They started as impermanent directions but are now extended different times.

A converse hybrid body corporate could formerly allow the American corporation to gain from the overseas tax credit devoid of acknowledging the primary revenues. For instance, an American parent company could have established a holding corporation in a nation which was seen as a conglomeration of another overseas authority. Pursuant to the flow-through regulations, the parent company owed foreign tax. Additionally, since it is not a distinct entity, the American parent firm is responsible, but the revenue can be reserved in the overseas entity which is an independent entity from the United States perspective (Picciotto & Mayne, 2016). In this situation, the structure is that there is a partnership for overseas drives but a company in the eyes of the United States. Hybrid entities are some of the bodies that accomplish tax benefits through being traded differently in the United States. Additionally, there is a hybrid instrument which is capable or avoiding taxation through being viewed as a liability in a certain state and equity in an alternative jurisdiction.

Sourcing Rules for Overseas Tax Credit and Cross Crediting

Revenues from a low-tax jurisdiction acknowledged in the United States can potentially evade taxation due to cross-crediting. It involves the utilization of excessive overseas taxes that are remitted in one country or on a single form of revenue to compensate the United States tax which could be attributed to additional revenues. In certain eras in the historic overseas tax, credit frontier was suggested on the basis of an individual country, but the rule attested to be hard to apply because of the likelihood of utilizing holding corporations (Picciotto & Mayne, 2016). Overseas taxation credits have over time been distinguished into various baskets in a bid to curb cross-crediting. The categorization has been reduced from nine baskets to two pursuant to the American Jobs Creation Act of the year 2004.

International business organizations have the liberty of choosing when to shift income and so they can organize comprehensions to optimize the advantages of general extent on the overseas taxation credit. In this sense, the organizations having incomes from countries whose taxes exceed those of the United States can realize revenues from the jurisdictions with suppressed taxes. Also, they can utilize the excess credit in offsetting the American tax which is due on the income. Past research has found that between deferral and cross-crediting, the United States multinational companies pay no tax in the country of overseas source revenues (Picciotto & Mayne, 2016).

The capacity to decrease US tax as a result of cross-crediting is increased since revenue which is supposed to be considered US revenue is seen as foreign income and this raises the overseas tax credit limit. It includes revenue from the United States exports which are rendered American sources of income. The Title Passage Rule tax provision provides for 50 percent of shipment revenues to be allotted to the nation on which the ownership rests (Doupnik & Perera, 2011). The royalty income from operating business organizations is another form of revenue which is taken to be an overseas source. For this reason; it is protected with foreign tax crests and it has turned into a significant source of overseas revenue. The benefit can take place in high-tax jurisdictions since fees are deducted from revenues. Also, interest revenue also benefits from this kind of overseas tax credit provision.

Sources and Estimate Costs of Corporate Tax Avoidance

There is lack of official projections of the costs incurred through global business tax avoidance. Statistics brought about by different researchers are not replicated in the larger taxation gap estimation. The extent of commercial tax circumvention is projected through different approaches and not all of them are for absolute evasion. Some of them only address aversion by the American international companies and not by the overseas parents of the US subsidiaries. Approximations of the probable income cost of revenue shifting by the offshore organizations vary significantly with some assessments exceeding $100 billion per annum (Doupnik & Perera, 2011). The one survey conducted by the IRS in this topic is an estimation of the global gross taxation gap in relation to transfer pricing on the basis of an audit of returns. However, the study cannot detect and bring to light all the non-compliance issues and avoidance mechanisms which appear to be or are legal.

Ideas regarding the speculative magnitude of income lost through profit shifting by the United States multinational companies could be located in the estimations of income gained from doing away with deferrals. If a majority of the profits from the low-tax jurisdictions are moved there in a bid to circumvent the United States tax rates, the projected incomes accruing from halting deferrals could offer an idea of the overall extent of income cost shifting profit by the United States parent companies (Doupnik & Perera, 2011). The Joint Committee on Taxation speculated the loss of revenue from deferrals to be roughly $83.5 billion in the 2014 fiscal year. On the other hand, the federal government’s estimation after ending the deferral stood at around $63.4 billion.

The estimations could either be an understatement or an overstatement of the cost of avoiding taxes. It is possible that there was an overstatement since they fail to look at the tax which might be gathered by the United States other than overseas countries on the proceeds moved to low-tax nations. For instance, Ireland imposes a taxation rate of 12.5% while that of the United States is at 35%. In this regard, bringing deferral to a halt would merely gather beyond the US tax above the Irish one on moved incomes or roughly two-thirds of the lost income. It is hard to establish a distinct estimate for the United States subsidiaries of overseas international organizations since there lacks a way through which to observe parent firms and their other branches (Doupnik & Perera, 2011). Different past surveys have stated that these organizations have less taxable revenues and others higher debt/asset ratios as compared to domestic companies. There are other different enlightenments that these various facets that do not result in spurs to move proceeds when they have overseas processes.

Significance of Profit Shifting Approaches

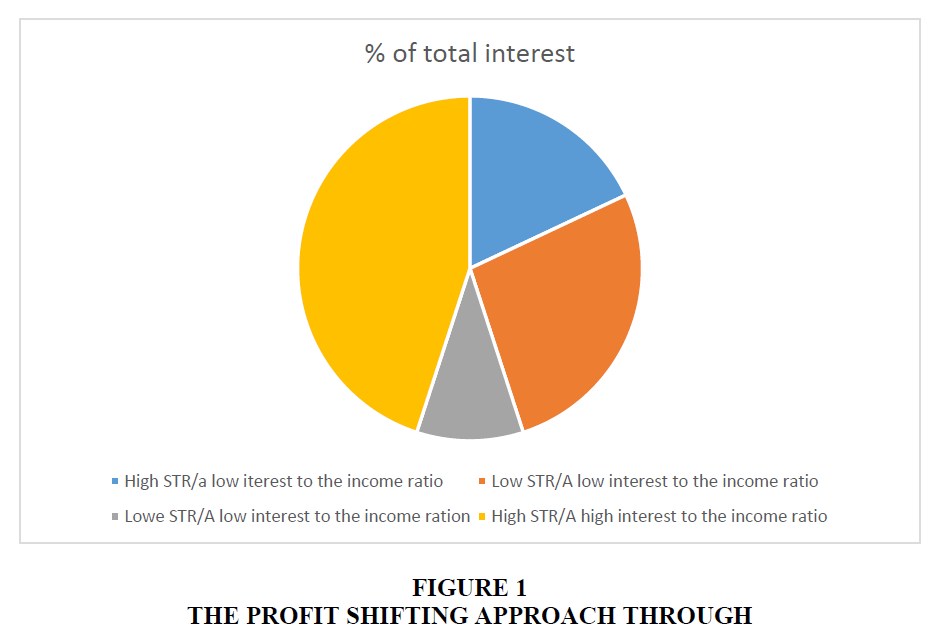

Different researchers have tried to establish the importance of techniques used in shifting profits between different tax profile jurisdictions. It has been established that roughly half its proceeds to shift is attributable to transfer pricing of intangible assets and the better part of the remainder to moving debt. Multinational companies save significant sums of money as a result of the check-the-box rules. Such gains come at the expense of high-tax cost hosting jurisdiction, but not for the United States (Fuest et al., 2013). Some of the estimations debated in the past surveys are in contradiction with the sources of profit shifting. The estimates of costing property may reflect errors or fraudulent activities such as money laundering, but not tax motives. Much of the moving is connected to trade activities in the high-tax jurisdictions. The chart below (Figure 1) demonstrates how profit shifting can be achieved through interest.

Tax Avoidance and Evasion by Individuals

There are different forms of individual tax evasion which are facilitated by the increasing multinational fiscal globalization and easiness of transacting through the Internet. People can by foreign investments directly offshore like bonds and stocks or deposit money in overseas bank accounts and fail to declare the revenue (Zucman, 2014). There has been the availability of minimal withholding data on individual tax remitters on this form of action. They could as well utilize structures shell conglomerates or trusts in a bid to dodge taxation on investment including those made in the United States which could exploit the US tax laws exempting capital gains and interest income of non-residents from taxation.

Instead of utilizing withholding, the United States has primarily depended on the Qualified Intermediary initiative where benefiting proprietors are concealed. In a bid to curb acts of evasion and unlawful avoidance, the European Union has established a multidimensional covenant in which the United States disregards (Zucman, 2014).

New establishments in data exchanges in information exchange are likely to impact on personal tax elusion both abroad and in the United States. In the year 2010, Congress passed the Foreign Account Tax Act. The Act upon becoming effective required alien financial institutions to file information regarding holders of assets subject to a withholding tax of 30 percent (Zucman, 2014). When enacted, income estimates did not seem to have significant effects and for this reason; the effectiveness of this piece of legislation is unclear.

Individual Income Provisions

The knack of American nationals to avoid taxation on US source revenue arises from the country’s regulations that do not enforce withholding taxation on multiple cradles of revenues. Capital and interest earnings do not pass through withholding tax. Non-portfolio interest, dividends and some rents are exposed to tax, but the treaty covenants broadly eliminate taxation on dividends (Mertens & Ravn, 2013). Additionally, even when payments are possibly exposed to withholding taxation, new approaches are established to change the assets to exempt interest.

In the current situation, concerns regarding capital flight could hold the country from altering this treatment of individual income. However, it comes with a deficiency of data presentation and deficiency of info distribution; allowing eligible Americans to avoid taxes on revenues earned from abroad. Nationals of offshore countries can evade tax and American standards for not collecting sufficient information is a part of this problem (Mertens & Ravn, 2013). A person, through the Internet, can start a bank account in the identification of a certain institution and this helps such an individual benefit from minimal taxes applied. Money is transferred electronically without the knowledge of state authorities and investments made abroad or right in the United States. Ventures established by foreigners in the interest-producing resources and maximum capital earnings are not subjected to withholding taxation in the US.

Constrained Information Sharing between Jurisdictions

In historical times, multinational levying of inactive assortment revenues by people has come as a topic of evasion since there lacks multilateral documentation of interest revenue. Even in the situations of consensual information distribution accords, the Tax Information Exchange Agreements, there were limits to sharing of data (Gallemore & Labro, 2015). A majority of these settlements are limited to felonious factors which form a trivial section of the incomes intricate and stance hard matters of proof.

Also, the arrangements at times need that the deeds associated with information being pursued amount to a crime in both jurisdictions and this can be a significant impediment in situations of tax circumvention. The OECD has assumed a prototypical covenant with the requirements of dual delinquency. It offers information when requested, calling for the United States and other nations to isolate probable tax violators before, without overriding the rules of bank secrecy (Gallemore & Labro, 2015). In certain cases, countries have minimal valuable information regarding the incidents and perpetrators of tax evasion.

United States Collection of Information on Income and Qualified Intermediaries (QI)

The US did not need its financial institutions to make an identification of the real recipients of exempt and interest bonuses. The IRS established a QI initiative in the year 2001 within which overseas banks receiving payments certified the nationalities of the depositors hence revealing the identities of America’s citizens. However, the QI initiatives should certify nationality; some of them depended on self-certification (Grinberg, 2012). QI programs are subjected to audits in a bid to detect potential tax abuse scandals which have in the past helped customers establish overseas developments. A nonqualified middle-party is supposed to expose the identities of the customer. This paves ways for the attainment of passive income like interest and reduced rates that come from taxation agreement, but there are queries regarding the accuracy of the admissions.

European Union Savings Directive

The European Union (EU), issued reserves dictate through which it established among the members a choice of either withholding tax or information sharing. The withholding or reporting covers the member nations and other non-member countries. Austria, Luxembourg and Belgium are some of the countries that have opted for the choice of withholding tax (Gérard & Granelli, 2013). Although this multi-lateral agreement helps these nations in tax administration, the United States does not take part.

Revenue Cost of Individual Tax Evasion

Various methodologies have been utilized in estimating tax avoidance in the context of corporate bodies in the economy (Hashimzade, Myles & Tran?Nam, 2013). On top of this estimation, the speculated rate of return and taxation are essential in the projection of revenue cost. Past research approximates a $50 billion value in personal tax dodging on the basis of an estimation of properties by high-end worth persons, having financed more than $1.5 trillion overseas. Applying a 10% rate of return, and a one-third average taxation, these individuals acquire an estimated $50 billion. If the earnings are in the form of interest revenue, the 10% rate of return is likely to be high. Applying a 15% tax rate is likely to result in about $23 billion. In the instance of equity stashes, if one-third of the returns are in disbursements and 50% of the capital additions are not recognized, the rate of taxation would be around 10% (Hashimzade, Myles & Tran?Nam, 2013). At the beginning of 2011, tax rate imposed on dividends and capital gains measured at about 20%, bringing about a loss of approximately $20 billion other than $15 billion. For purposes of interest, stakeholders can make tax-free proceeds in the range of 4 to 5% on the local bonds and domestic state to earn 5% returns after tax. In this instance, the estimate comes to around $40 billion.

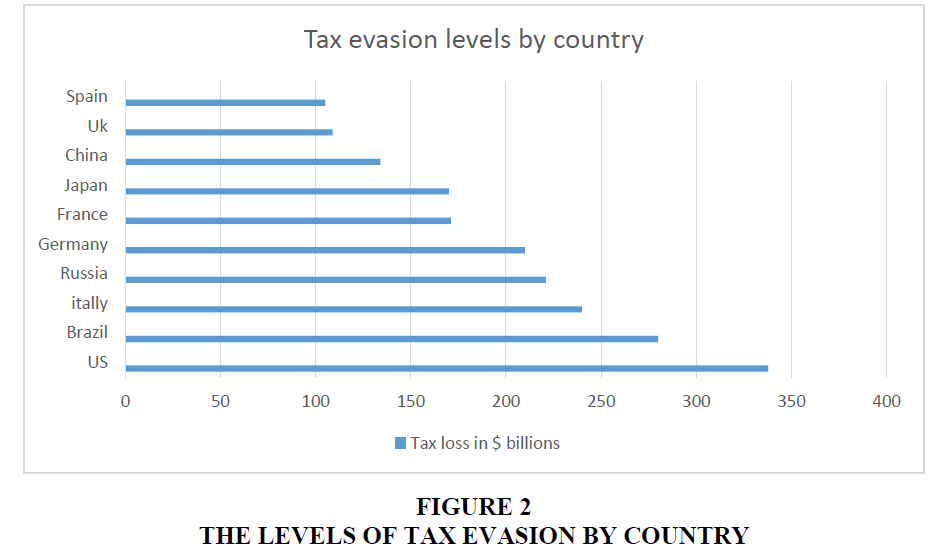

According to the Tax Justice Network, there is a global loss of revenues for all nations measuring at $255 billion from tax evasion at personal levels, applying a 7.5 percent yield and 30 percent rate of taxation. The conventions are in tandem with the $33 billion loss in the case of the United States applying the $1.5 trillion amount. The global statistics are in line with $11 trillion in overseas wealth. The most recent data position the wealth at $21 trillion to $32 trillion, potentially doubling or tripling the approximations (Hashimzade, Myles & Tran?Nam, 2013). For this reason; the cost for the United States is likely to be more, approaching and almost at $100 billion. In the year 2014, it is estimated that there was a $1.2 trillion accumulation of wealth in the US financial wealth overseas on the grounds of irregularities in investment data, hence resulting in loss of taxation to the tune of $36 billion (Hashimzade, Myles & Tran?Nam, 2013). There is lack of legitimate and accurate means of establishing whether the top-ranking cases of prosecuting tax evaders and tax amnesty may have minimized the estimated amounts of wealth invested overseas. It is important to note that this puts the US, as the country with the highest level of tax evasion. Figure 2 below shows the levels of tax evasion by country.

Recommendations

Policy options for Addressing Corporate Profit Shifting

A large portion of commercial tax income loss comes from endeavors that are either lawful or have a lawful appearance. For this reason; it becomes difficult to look into these issues rather than with alterations in the law of taxation. Results will be ideal if there is a mutual universal collaboration and standpoint regarding the aspects of combating international tax evasion at a corporate level (Giovannini, 2013). As it is in the modern setting, the probabilities for a global cooperation is likely to play a larger role in the options for handling individual evasion as compared to tackling it on a corporate platform. This section of the article touches on avenues of combating international tax evasion.

Repeal Deferral

Among the potential methods of mitigating recompenses of shifting profits is to rescind deferrals or introduce real global taxation of overseas source revenues. Corporate bodies would be subjected to the current tax rates on the revenues of their overseas branches. However, they continue to benefit from alien tax credits (Giovannini, 2013). According to the quoted projections, the change could currently go up from $63.4 billion to $83.4 billion annually. Different issues revolving around rescheduling have concentrated on the true impacts of retraction on the apportionment of capital. Customary, an economic study has postulated that getting rid of deferrals is likely to result in efficiency (Giovannini, 2013). There have been arguments to the effect that these gains would be compensated through the loss of fabrication of certain effectual organizations from the high-tax jurisdictions. Other scholars have advocated for sustaining the existing system or shifting to the other course of regional taxes.

The repeal of deferral could eradicate the value of the techniques of planning. However, there are concerns that international organizations could evade these impacts of repeal through having their parent firms incorporated in other jurisdictions that provide for deferral. Also, mergers and acquisitions could be applied in order to counter the effects of deferral. Mergers could be used even if they engage significant changes in the firm that could not be undertaken for the potential meager taxation benefits (Giovannini, 2013). There is also the possibility that direct portfolio investments in overseas companies will take place. A substantial growth has been experienced in the direct investment, although the proof postulates that it has been made because of portfolio diversification. It is not in the interest of tax avoidance on the side of the corporations.

Narrower proposals for addressing tax avoidance and deferrals would be to tax revenues earned in tax havens. It will involve eradicating deferrals for certain havens, more so the ones characterized by evasions the most (Giovannini, 2013). In such circumstances, it becomes crucial to distinguish a tax haven. Some jurisdiction deemed to be tax havens do not meet the provisions of one and this leaves a scope for the avoidance of corporate tax. Additionally, organizations can move some operations to the lower-tax nations hence increasing the available overseas tax credits available, resulting in losses in US income. There have been articulated concerns that listing certain tax haven states would result in supportive slants like sharing of tax info agreements (Alm, 2012).

Addressing Individual Evasion

A majority of options aiming at looking into individual avoidance is more about information sharing and additional implementation. Some choices engage vital alterations in the law like moving from a residence to a basis grounds for inert revenues. Meaning, the United States will tax the unreceptive revenue earned within its boundaries as it is the circumstance for companies and other forms of active incomes (Alm, 2012). The alteration implicates other efficiency and economic impacts that are not desired.

Information Sharing

The EU directive on reporting information or withholding tax is a good example of a multilateral approach to addressing the issue of sharing data. The current treasury should concentrate on bilateral agreements in a bid to accomplish the exchange of information. However, the United States also supposed to look into collaboration with the G-20 and OECD and other suitable establishments to enhance information. Also, the country is supposed to convince tax havens to engage in exchanges within the confines of the OECD model (Alm, 2012). The Tax Justice Network has come up with the idea of the United Nations developing a worldwide tax cooperation standard. It will do so by setting up a panel to establish acquiescent states and repudiate recognitions to jurisdictions that are not compliant. The body has also postulated that the World Bank and the IMF should carry out country evaluations and address the issue of tax compliance.

Increasing Bilateral Information Exchange

Different stakeholders have proposed an increment in the latitude of consensual material agreements to allow for automatic and often information interactions. The suggestion would need the United States banks to expand their aspect of collecting information. Information exchange is supposed to be associated with civil and criminal issues. Calling for misgiving of criminality rather than tax circumvention and would predominate bank confidentiality regulations in different tax havens (Alm, 2012). Treasure has projected just 16 nations, but there lacks a concrete reason for limiting the provision in such a stringent way. Instead, treasury could apply its existing authority not to conduct information exchange which is likely to be abused by non-democratic alien administrations.

Improving International Tax Compliance

Scholars have proposed a carrot and stick methodology of handling tax harbours. They believe that some benefits of the tax refuges trickle down to indigent populations and the specialists offering legal and financial services. Different stakeholders in the economy advocate for a traditional aid of moving away from the overseas activities. For the non-cooperating tax shelters, there is the suggestion that Treasury uses its existing power to rebuff interest benefits exemption (Alm, 2012). Tax havens cannot continue with their existence, not unless the develop nations allow them since finances are not productive in these regions.

A significant component of the Stop Tax Haven Abuse legislation is to position to the liability of evidence before the jury on the taxpayer. There is another move in the obligation of evidence for the accounts with non-qualified middle-parties for documenting a Foreign Bank and Financial Account Report (FBRAR) (Palan, Murphy & Chavagneux, 2013). President Obama’s plan could develop a presupposition that finances in alien accounts are significant enough to call for an FBRAR; it is needed when amounts go beyond $10000 (Palan, Murphy & Chavagneux, 2013). It treats the failure of filing for amounts more than $200000 as deliberated and this provides for criminal proceedings and larger civil punitive measures.

The Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act comes with a provision for treating any organization, trading publicly or having assets in excess of $50 million as an American corporation. The provision allows for hedge funds, but would not impact on branches of international companies since key decisions are reached the parent firms. Such an establishment comes with a detrimental impact on the US hedge fund sector where the overseas firms attract tax-exempt local investors and aliens willing to avoid filing tax returns (Palan, Murphy & Chavagneux, 2013). Also, it is likely to attract American tax avoiders and the statutory reprieve for American tax-exempt investors.

In a bid to enhance tax compliance in a global context, it is important to strengthen penalties and enforce them to evaders without fear or favour. Increased punitive measures are provided for in the projected Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act and the Finance Committee Draft. There should be punitive measures enforced on individuals and corporations that do not file FBRARs (Shaxson, 2012). Also, stringent punitive measures are supposed to be imposed on dishonest tax shelters, failing to file data regarding alien trusts and different overseas transactions. The Act has an establishment that lawful sentiment assuming the place that transactions are more likely not to succeed for taxation will not protect taxpayers from imminent punitive measures (Shaxson, 2012).

Conclusion

In taxation, there is a discourse of individuals who are unwilling to pay up and hence they seek legal means or ways similar to legality in avoiding and evading paying taxes. In this sense, it is important to deal with such cases and ensure that all eligible parties, either individuals or business organizations pay taxes to the relevant authorities. International companies artificially move proceeds from the high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions utilizing various approaches such as moving liability to high-tax jurisdictions. Duty on revenues on alien subsidiaries is deferred until when it is repatriated to the home country and this enables revenues to escape American tax perchance indefinitely. Taxation of passive revenues has been decreased substantially through hybrid entities that are treated in varying ways in various jurisdictions. Revenues from proceeds that are fixed are often shielded by alien tax credits on other incomes. Averagely, little tax is paid on overseas revenues of American organizations. There is sufficient evidence that substantial amounts of profit shifts happen, but the income cost estimations vary significantly. Also, evidence shows a substantial increment in international organizations’ profit movement over the recent past years. Estimations show that over $100 billion of revenues is lost in tax evasion and avoidance by the corporate bodies. Individuals evade tax on passive revenues like capital gains, dividends and interest by failing to declare the incomes earned overseas. Since interest paid to alien beneficiaries is not taxable, people evade taxes based on the United States source revenues through establishing trusts and shell corporations in tax haven countries. There are provisions that look into the issue of profit shifting by international business organizations that mainly advocate for changes in the law of taxation. Dynamics in the anti-abuse requirements have been established in broad tax restructuring suggestions throughout the years more so in Congress. Provisions that guide individual evasion include more information sharing and allowing for increased implementation such as moving the task of evidence to the taxpayer.

References

- Alm, J. (2012). Measuring, explaining and controlling tax evasion: Lessons from theory, experiments and field studies. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 54-77.

- Barrios, S. (2012). International taxation and multinational firm location decisions. Journal of Public Economics, 96(11), 946-958.

- Czinkota, M.R., Ronkainen, I.A., Moffett, M.H., Marinova, S. & Marinov, M. (2011). International Business (European Edition). Wiley.

- Doupnik, T. & Perera, H. (2011). International accounting. European Accounting Review, 27-52.

- Egger, P. (2010). Corporate taxation, debt financing and foreign-plant ownership. European Economic Review, 54(1), 96-107.

- Fuest, C., Spengel, C., Finke, K., Heckemeyer, J.H. & Nusser, H. (2013). Profit shifting and 'aggressive' tax planning by multinational firms: Issues and options for reform. ZEW Discussion Paper No. 13-078, Mannheim.

- Gallemore, J. & Labro, E. (2015). The importance of the internal information environment for tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(1), 149-167.

- Gérard, M. & Granelli, L. (2013).From the EU savings directive to the US FATCA, taxing cross border savings income. Discussion Papers (IRES-Institut de Recherches Economiques et Sociales), 7, 82.

- Giovannini, A. (2013). International capital mobility and tax avoidance. PSL Quarterly Review, 44(77), 71-78.

- Gravelle, J.G. (2016). Tax havens: International tax avoidance and evasion. DIANE Publishing, 39-47.

- Griffin, R.W. & Pustay, W.M (2012). International business (Seventh Edition). Pearson Higher Ed.

- Grinberg, I. (2012). Beyond FATCA: An evolutionary moment for the international tax system. Georgetown University Law Centre 21.

- Hashimzade, N., Myles, D.G. & Tran-Nam, B. (2013). Applications of behavioural economics to tax evasion. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27(5), 941-977.

- Karkinsky, T. & Riedel, N. (2012). Corporate taxation and the choice of patent location within multinational firms. Journal of International Economics, 88(1), 176-185.

- McDaniel, P.R., Repetti, R.J. & Ring, D.M. (2014). Aspen student treatise for introduction to united states international taxation. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.

- Mertens, K. & Ravn, M.O. (2013). The dynamic effects of personal and corporate income tax changes in the United States. The American Economic Review, 103(4), 12-17.

- Mintz, J.M. & Weichenrieder, A.J. (2010). The indirect side of direct investment: Multinational company finance and taxation. MIT press.

- Palan, R., Richard, M. & Christian, C. (2013). Tax havens: How globalization really works. Cornell University Press.

- Picciotto, S. & Ruth, M. (2016). Regulating international business: Beyond liberalization, Springer.

- Shaxson, N. (2012). Treasure islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world. Random House.

- Zucman, G. (2014). Taxing across borders: Tracking personal wealth and corporate profits. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 121-148.