Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 3S

The Accessibility of Institutional Support Services to Immigrant Owned Survivalist Craft Businesses in Cape Town

Samson Nambei Asoba, Walter sisulu University

Nteboheng Patricia Mefi, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

This study explored the accessibility of support services to immigrant-owned survivalist craft enterprises in Cape Town, using a mixed methodology design. One hundred and fifty owners of survivalist enterprises responded to a closed-ended questionnaire, which sought to establish if support services from relevant institutions were accessible to them. These results were considered together with the results of interviews with five support institutions in answering the question “What challenges are faced by survivalist immigrant-owned craft enterprises in accessing support services for growing their businesses?” It was found that the immigrant-owned survivalist enterprises faced accessibility challenges related to documentation, registration and official recognition to obtain support from relevant institutions. It was recommended that immigrant-owned micro craft businesses in Cape Town should establish strong links with support institutions such as incubation centres, financial institutions, education and training institutions so that they receive regular relevant support for growth. Collectivism in negotiation with the government on the challenge of business regulations for immigrants should be initiated. Stakeholders in the immigrant craft businesses should review and endeavour to resolve the regulation challenges they face so that the businesses can grow.

Keywords

Survivalist Enterprises, Support Institutions, Smmes, Immigrant Craft Enterprises.

Introduction

National development discourse is pervasive across all nations. Developmental matters appear to perpetuate in levels and phases that are inspired by innovativeness, creativity and technology. This appears so when one considers the history of civilisation and present developmental issues among nations across the globe. South Africa crafted the National Development plan (NDP) to propel its economic advancement and to provide targets and milestones to check development. Unemployment is a negative associate of development since it affects the general quality of life within a nation. As such, creating employment remains an essential ingredient of the developmental matrix of many nations. Bowmaker-Falconer and Herrington (2020) restated the official South African unemployment rate as 29.1% at the end of 2019. This should be assessed in a context in which the NDP had envisaged the drop of the unemployment rate to 14% in 2020 (Zarenda, 2013). Further conclusions to the unemployment situation in South Africa should be considered with reference to the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) group in which the unemployment rates are Brazil - 11%; Russia - 4.6%; India - 7.2%; and China - 3.6%.

Literature Review

Even though immigrant-owned craft businesses contribute to reducing the unemployment rate in South Africa, many of them fail to grow and collapse (Tengeh, 2011). This problem means that efforts to reduce unemployment and grow the economy remain unaccomplished. The problem manifests in increasing as opposed to decreasing unemployment rates. This study considers immigrant-owned small craft businesses that are set up by immigrants in Cape Town. Like numerous other South African cities, Cape Town is home to many immigrant communities. This observation is espoused by van Eeden (2011) who reports that a notable section of immigrant communities reside in Cape Town. Cape Town is well known as a peaceful and attractive destination and is a prime tourist centre, offering popular features such as Table Mountain, Cape Point, the Winelands and the South African Museum. According to Kaiser and Associates (2005), immigrant entrepreneurs own more than half of the survivalist and micro retail craft enterprises in Cape Town. Such retail craft outlets are mostly found in Stellenbosch, Hout Bay, Franschhoek and Green Market Square craft markets.

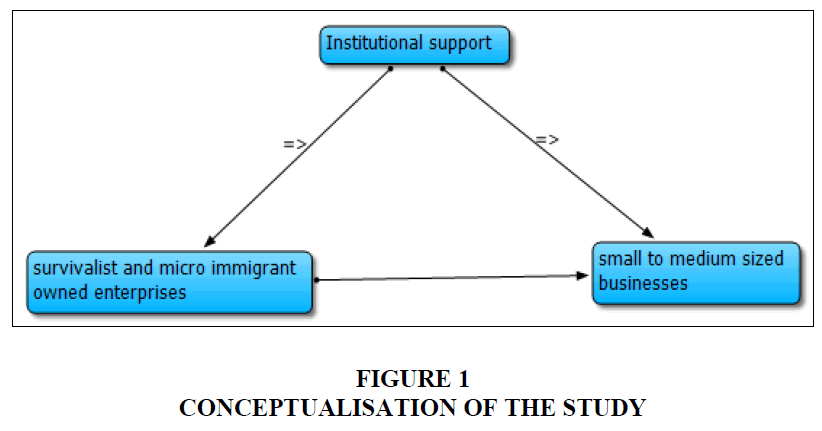

Postulations from the block mobility theory suggest that immigrants are involved in selfemployment (craft enterprises) due to failure to obtain formal jobs and face segregation and injustices in employment matters (Bates, 1996; Simelane, 1999; Clark & Drinkwater, 2000; Bogan & Darity, 2008:2010; Tengeh, et al., 2011; Fatoki, 2014). Furthermore, complicated immigration requirements inhibit immigrants from seeking job positions, resulting in them settling for self-employment (Peberdy & Crush, 1998; Centre for Development and Enterprise [CDE], 2006). Once established, micro craft businesses owned by immigrants fail to grow due to a litany of factors. The support of key relevant institutions is important for the growth of immigrant-owned craft enterprises. The progression of micro and survivalist immigrant-owned enterprises to small and medium-sized businesses can be viewed as a way of tackling the rate of unemployment, raising standards of living and making a favourable impact on the tax base.

Growth of Immigrant-Owned Craft Enterprises and Institutional Support

The growth of small businesses require institutional support. South Africa has recognised the need for institutional support through the establishment of various structures and institutions for the development of small businesses. The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) was established by the South African government to provide monetary, financial, technological, infrastructural and developmental resources to small, medium and micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs) in an attempt to facilitate and sustain growth. Khosa and Kalitanyi (2014:205) assert that although legislation, such as the White Paper, was formulated in 1995 under the supervision of the DTI as a national strategy to support and create an enabling environment for SMME growth, it is believed that a significant proportion of immigrant-owned craft enterprises hardly benefited from any programmes because immigrants are non-nationals. Despite this situation, there has been consistent recognition that immigrant-owned enterprises can significantly propel national development if assisted by the government to become viable enterprises.

A further study question was “What challenges are faced by survivalist immigrant-owned craft enterprises in accessing support services for growing their businesses?” This question is conceptualised in Figure 1.

Support Institutions For Small Businesses in South Africa

Several institutions support small businesses and ensure economic participation of the unemployed through entrepreneurship. Table 1 depicts some of the support institutions in south africa and the kind of support that they provide.

| Table 1 Support Institution | |

| Support institution | Nature of support |

| Ntsika Enterprises Promotion Agency | • Identifying SMME priorities and to design interventions to develop and promote SMMEs (Ntsika, 2002) • Creating an enabling environment and provide essential information to the relevant policy-makers, business development practitioners and emerging entrepreneurs |

| Khula Enterprise Finance Limited | • Facilitating provision of loans and equity capital to small, medium and micro enterprises • Provide credit guarantees to banks on behalf of SMMEs that cannot provide collateral (DTI, 2005) |

| South African Micro-Finance Apex Fund | • Build a vibrant micro finance industry in South Africa. • provide affordable finance and access to financial services for poor South Africans and disadvantaged communities (Western Cape Government, 2006) • Partnering with other outreach programmes in the community such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and local entrepreneur services • offers three main products of micro-credit, loan fund and institutional capacity building and saving mobilisation |

| National Empowerment Fund | • Promote a better universal understanding of equity ownership through promoting a competitive and efficient economy and generating employment among historically disadvantaged people. • Encourage the culture of saving and investment among disadvantaged groups and foster entrepreneurship. The National Empowerment Fund (NEF) also aimed to assist historically disadvantage people who wanted to start businesses, or those with existing businesses, to acquire shares in existing white-owned enterprises (DTI, 2005 |

| National Youth Development Agency | • Deal with the needs of the South African youth and women who are looking for self-employment avenues • Ensure that stakeholders prioritise youth development by changing the central function of financial assistance to education and skills development, thus ensuring grants to young entrepreneurs. In line with this objective • Gave young entrepreneurs the chance to access non-monetary as well as financial assistance, from a minimum of R1 000 to a maximum of R100 000 for every youth and woman. |

| Small Enterprises Development Agency | Assist entrepreneurs to start their businesses and create jobs • Support programme includes teaching entrepreneurs how to write business plans, mentoring and coaching, and designing marketing material • Design and implement a standard national delivery network with the aim of providing services to SMMEs. |

| Small Enterprise Finance Agency | • Respond to the challenges of access to finance for start-up and expansion of SMMEs • Finance business loans, funding for joint ventures, non-financial support and institutional indemnities |

Methodology

The study followed a mixed research design based on the triangulation of both qualitative and quantitative data. Johnson, Onwuegbuzie and Turner (2007) state that most researchers use the mixed approach because it best answers research questions. Johnson et al. (2007) further indicate that a mixed method can be utilised in a single study. This approach is associated with pragmatism and advocates of the mixed method approach state that deeper knowledge is acquired by using a mixed approach (Mafuwane, 2012). Mafuwane adds that a mixed method facilitates extensive reporting and comprehensive understanding in a given study. Johnson et al. (2007); Mafuwane (2012) concur that the multiple research method is more comprehensive in addressing a complex social phenomena and is appropriate for collaborative and applied research. The mixed method research approach was utilised in this study because both quantitative and qualitative used together not only complement each other during data collection and analysis but also assist the researcher to address the problems under investigation and answer the research questions. Another aspect of a mixed method is its power in providing information, data collection and interpretation that is more valid and reliable (Johnson et al., 2007). Given the complexities and the nature of the research problem necessitated that two different research instruments were used in this research project, namely questionnaires and interviews, which complemented each other and allowed the researcher to get to the root of the problem. Hence, the pragmatic research paradigm was adopted in this study. The study sought to establish the availability and accessibility of institutional support to survivalist immigrant-owned craft enterprises in Cape Town. The investigation covered four craft markets in Cape Town, namely Green Market Square, Stellenbosch, Hout Bay and Franschhoek.

In this study, the sample comprised immigrant entrepreneurs who own survivalist, micro, small or medium enterprises that are three and a half years old, located in the selected craft markets in Cape Town. Two sampling procedures were utilised in this study purposive nonprobability and snowball sampling. According to Bernard (2006), purposive sampling is used to select participants who possess valuable knowledge and contribute valid responses to the study. In line with Bernard, the purposive non-probability technique was utilized to select participants from institutions in Cape Town to identify the provision of support given to immigrant-owned craft enterprises and who could contribute valid responses to this study. Furthermore, snowballing was also utilised to identify immigrant entrepreneurs who own survivalist, micro, small or medium enterprises. This can be compared to the views of Tengeh (2011), who argues that the snowball sampling technique can involve a few potential participants who are identified to begin with, whereafter they are asked to suggest others known to them who also meet the necessary criteria for inclusion in an investigation. A broad range of issues can impact sample size in qualitative research; however, the guiding principle should be the notion of saturation (Tengeh et al., 2011). Saturation may be described as when after numerous interviews, a point is reached where the researcher is getting a high rate of repetitive responses and nothing new emerges. This indicates saturation and the interview process can be stopped. Tengeh et al. (2011) and Khosa and Kalitanyi (2014) agree that for a reasonable statistics analysis, the qualitative sample size will be achieved only when data collected from interviews becomes saturated. Furthermore, the qualitative sample composition is achieved only when the information from the interviewees becomes saturated (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003:172). Based on the population (210 immigrant-owned survivalist and micro craft enterprises) in the selected markets, the quantitative sample size was estimated at 150 survey questionnaires to be distributed to managers/owners of immigrant-owned survivalist and micro craft enterprises. According to Raosoft (n.d.), a webbased platform provides a more reasonable sample size calculation, provided the targeted list is adequately accessed. Applying the Raosoft platform, a confidence level of 95% and an error margin of 5% was considered.

Discussion

There was a 100% response rate to the 150 questionnaires administered, which revealed that 90% of respondents were owners of the micro and survivalist craft businesses that participated in the study. In addition, all the respondents were from craft businesses that had survived for more than 3.5 years. The biographical information of the respondents was 70% males compared to 30% females, the majority (64%) of the respondents who participated in the study were in the 20–40 age group and 65% of the respondents had attained secondary education. The least number of respondents had a Master’s degree (1%) and a PhD degree (1%). In terms of location, 55% of the micro and survivalist craft businesses were located in Stellenbosch, 18% were from Greenmarket Square in Cape Town, Hout Bay craft market contributed 15% of respondents, while 11% operated in Franschhoek. The nationalities of the respondents was 16% of the respondents were from Cameroon, while 15% were from Zimbabwe. The least number of respondents came from Sudan (2%), Egypt (2%), Angola (3%) and other countries. Lastly, the majority (70%) of the participants were married.

Findings From the Quantitative Study

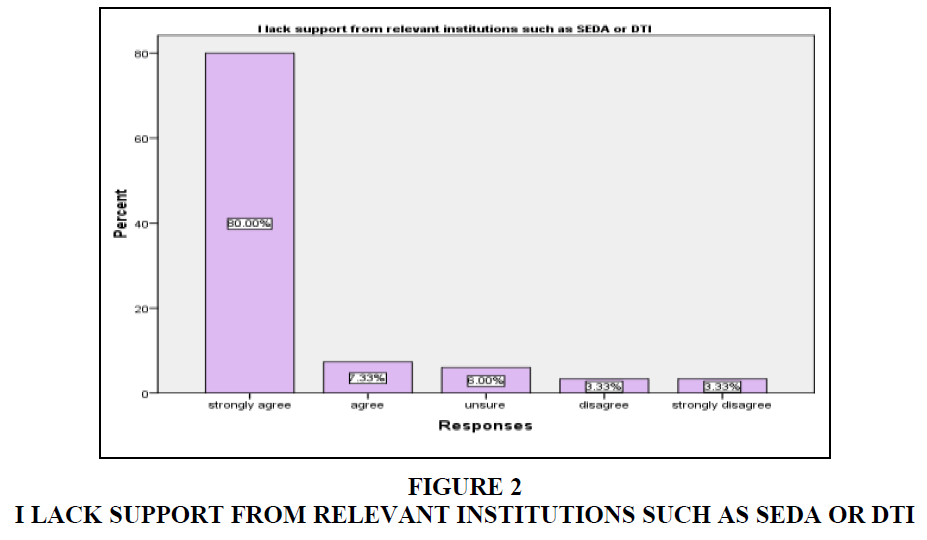

Institutional Support From Relevant Institutions

As shown in Figure 2, a significant majority (80%) of respondents strongly agreed and 7% agreed that micro and survivalist immigrant craft enterprises lack support from relevant institutions. It should be emphasised that support from relevant institutions is a key factor in the growth of immigrant-owned survivalist enterprises. Of the rest of the respondents, 6% were unsure, 3% disagreed and a further 3% strongly disagreed with the statement. The conclusion drawn is that most micro immigrant-owned craft enterprises lack support from relevant institutions.

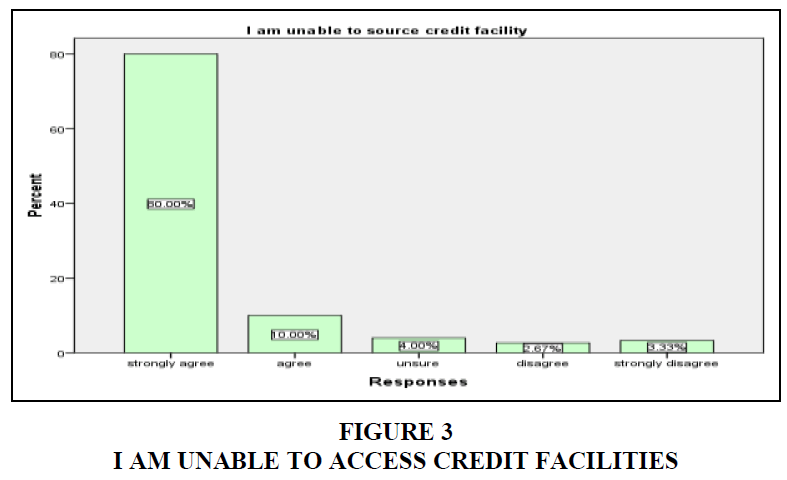

Availability of Credit Facilities

The argument in this section is that credit facilities are a form of stakeholder support that influences the growth of immigrant-owned survivalist enterprises. As shown in Figure 3, 80% of the respondents strongly agreed that they were unable to source credit facilities, 10% agreed, 4% were not sure, 3% disagreed while another 3% strongly disagreed with the statement. This demonstrates that most micro and survivalist immigrant-owned enterprises are unable to access credit facilities.

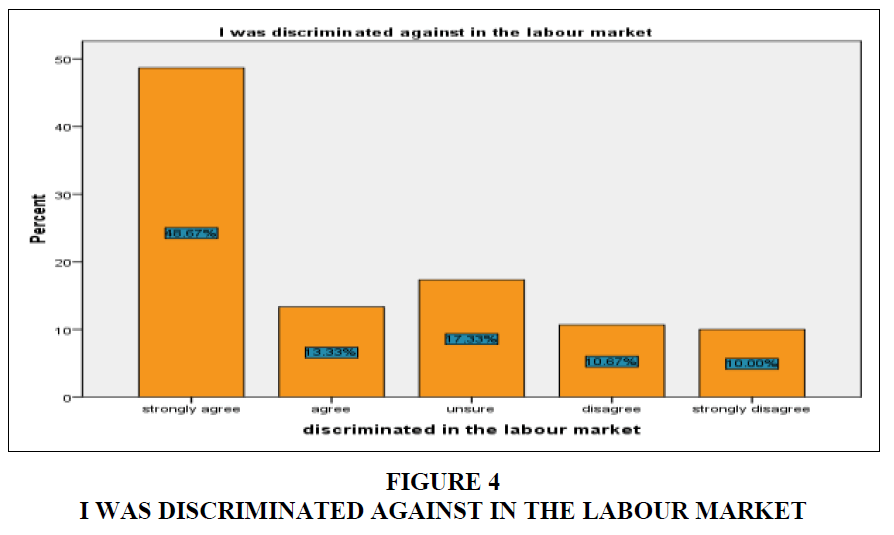

Fairness in Discrimination in the Provision of Institutional Support

As shown in Figure 4, 49% of the respondents strongly agreed that discrimination against them in the labour market made them decide to form their craft businesses and 13% agreed, while 17% were unsure, 11% disagreed and 10% strongly disagreed. This implies that discrimination in the labour market could be a driving factor for the formation of immigrantowned craft businesses. The finding should be taken in the context of the research problem, which lies in the growth prospects of immigrant-owned businesses.

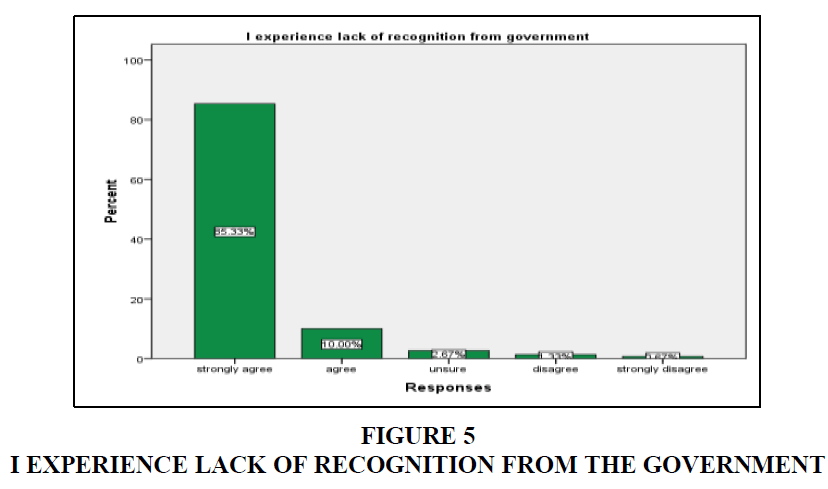

Recognition From Support Institutions

This section should be analysed in the context where entrepreneurship has largely been described as a vehicle for both economic growth and tackling unemployment. The immigrant craft businesses have the potential of growth, which could improve the rate of unemployment and the economic growth of the country. A combined 95% of respondents strongly agreed and agreed that they experience lack of recognition from government. A mere 2% strongly disagreed and disagreed, while 3% were unsure about the statement. These results are graphically represented in Figure 5. The finding clearly indicates that this factor must be considered in the proposed framework for growth.

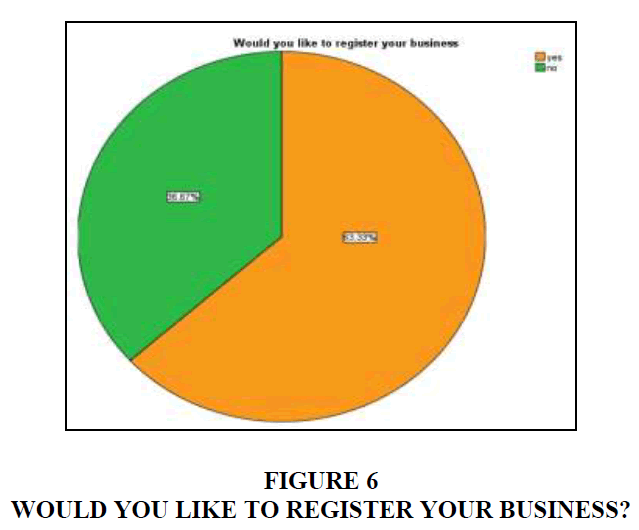

The Need to Register the Business

Given the situation regarding the state of immigrant-owned craft businesses, the study found that the majority of respondents (63%) felt there was a need for them to formalise their businesses through registration, while the remaining 37% believed it was not necessary to register their businesses. These findings are graphically presented in Figure 6.

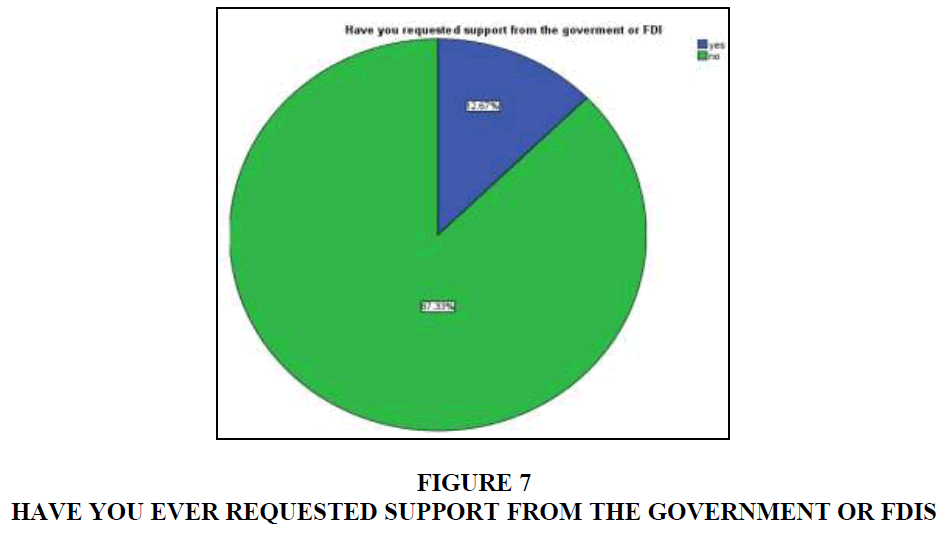

Request for Assistance From Government or FDIs

The results of the last question on the questionnaire are illustrated in Figure 7. This question sought to establish if the respondents had ever requested any support from the government or from FDIs.

It was found that a very significant majority (87%) of respondents had not requested any support, while only 13% had.

Results of the Interviews With Financial Development Units

Respondents’ details

Even though the study had targeted a greater number of respondents for this study, only five were available and provided information that was required for the study. As is shown in Table 2, four respondents were from SEDA and one was from an incubation centre (simply identified as X).

| Table 2 Biographic Details of Respondents | |||

| FDI | Years in service | Position | |

| Respondent 1 | SEDA | 4 years | Centre Administrator |

| Respondent 2 | SEDA | 4 years | Business Advisor |

| Respondent 3 | SEDA | 8 months | Business Incubation Specialist |

| Respondent 4 | Incubation Centre X | 5 years | Admin and Marketing Officer |

| Respondent 5 | SEDA | 3 years | Technical Manager |

Services Offered by the Organisation

It was found that the organisation provides a wide range of services. Respondent 1 indicated that SEDA provides seven services, being initiate and provide information about entrepreneurship opportunities; registration of businesses; training in entrepreneurship skills; business idea/concept development; Market research; Business plan development; Access to funds; and Mentoring and coaching. Respondent 4 mentioned that Incubation Centre X offers various SMME development services and access to resources. Respondent 3 added that SEDA provided business support services such as business analysis, planning and advisory services. Respondent 5 stated that SEDA coordinates and implements entrepreneurship. The responses from question 3 demonstrate the wide scope of services available to SMMEs that are provided by SEDA and Incubation Centre X.

Cost of services

All the respondents indicated that their organisations provided their services free of charge as indicated in Table 3

| Table 3 Are the Services you offer free of Charge | |

| Do you offer services free of charge? | |

| Respondent 1 | Yes |

| Respondent 2 | Yes |

| Respondent 3 | Yes |

| Respondent 4 | Yes |

| Respondent 5 | Yes |

Customers of the Organisations

As shown in Table 4, a broad category of potential entrepreneurial and SMMEs can receive assistance from SEDA and the incubators. These range from college and university graduates who wish to undertake a business venture, to members of the community who also have a business idea to execute.

| Table 4 Who are your Customers? | |

| Who are your customers? | |

| Respondent 1 | College students /Graduates and general public |

| Respondent 2 | Students/Community Entrepreneurs |

| Respondent 3 | SMMEs and entrepreneurs |

| Respondent 4 | Aspiring student entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs in the automotive sector and community based entrepreneurs. |

| Respondent 5 | Youth between the ages of 18-35 who have a business idea or an existing business, the offer is also extended to community business owners who are older than 35. |

Criteria for Providing Services

Only Respondent 2 mentioned the need for a South African identity card in identifying potential entrepreneurs to assist. It appears that the main criterion for assistance is the existence of a viable business idea that can be expected to satisfy a certain need in the community. This speaks to immigrant survivalist micro businesses since it is required of them to have a clear business idea right from the start shows in Table 5.

| Table 5 What Criteria Must one meet to be Served at your Organisation? | |

| What criteria must one meet to be served at your organisation? | |

| Respondent 1 | One must have characteristics of an entrepreneur Have a business concept or minimal viable product that needs to be tested to the market Technical and business skills Technical skills in the automotive sector |

| Respondent 2 | Have South African identity, Have a registered business or business idea |

| Respondent 3 | A minimum viable product/service with a market potential |

| Respondent 4 | Customized criteria related to RSA regulatory environment e.g. Companies Act |

| Respondent 5 | viable business idea, start-up or an operational business |

Inclusion of Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Support Services

While Respondents 1, 2 and 3 agreed that they include immigrant entrepreneurs in offering their services, Respondent 4 answered ‘No’ and Respondent 5 stated:

Include them where? Criteria are mostly aligned with prevailing socio-economic and transformation policies of regulations of the country.

In addition to the above, Respondent 5 said:

Criteria for providing support to immigrant entrepreneurs depend on what is applied for or support required. For example support with funding requires a South African applicant but SMME support funded by international partners like EU/USAID is inclusive.

Respondent 5 implies that whether immigrant entrepreneurs obtain assistance or not depends on the policies and regulations prevailing at the time. Respondent 1 stated conditionality:

Immigrant entrepreneurs are assisted as long as they are compliant with South African SMME regulations and are legalized.

These sentiments are in line with the conditionality put by Respondent 2, that the immigrant should possess a business permit. When considering the negative responses from Respondents 4 and 5 and the conditionalities put forward by those who agreed, it can be concluded that these interviews did not provide a conclusive answer on whether immigrant entrepreneurs can get assistance from SMME development institutions or if the service is unavailable to them.

Recognition of Immigrant-Owned Survivalist and Micro Entrepreneurs As Part of the Smmes in South Africa

Table 6 & 7 reflects that even though most of the respondents acknowledge that small immigrant craft businesses could be important players in the South African economy, it appears that some of them, as indicated by Respondent 4, are not completely free to offer full assistance owing to national regulatory issues. These conclusions are consistent with reports in the literature. Altinay and Altinay (2008) assert that immigrants are sidelined by financial institutions. Mkubukeli and Tengeh (2015) also report that government and other institutions are reluctant to help small businesses and prefer to assist large firms. A study conducted by Tawodzera, Chikanda, Crush & Tengeh (2015) found that contrary to the popular perception in the media that migrants have a negative impact on the South African economy, the findings demonstrate a positive economic contribution to some cities and towns.

| Table 6 Do you Recognise Immigrant-Owned Survivalist and Micro Entrepreneurs as part of the SMMES in South Africa? | ||

| Respondent 1 | Yes | Though they are not part of our KPIs, we report about them since they also contribute to the economy of our country. We offer them non-financial business support services; however, they do not qualify for access to finance. By recognising them as part of SMMEs in SA, it gives us an indication of how many SMMEs we have in our region, which are owned by immigrants and in which sectors these immigrants operate. |

| Respondent 2 | Yes | Their businesses contribute to the South African economy and employment creation. |

| Respondent 3 | Yes | Question not clear! Recognise them how, by our ACTS, policies, Some acts recognise immigrant? There are participants, they trade? Be specific, they recognised with regards to what? |

| Respondent 4 | No | Most of their businesses are not registered and do not comply with small/micro enterprise regulations, which makes it harder for them to partake or contribute to the South African economy. Though they do employ some local unemployed people within communities, some businesses do contribute. |

| Respondent 5 | Yes | Immigrant SMMEs contribute to South Africa’s economic activity and GDP and create job opportunities for many South Africans. |

| Table 7 Do you see Immigrant-Owned Survivalist and micro entrepreneurs as Contributing to the Economy of South Africa? | ||

| Respondent 1 | Yes | As an Incubator we ensure that these SMMEs comply as per the regulations of the country and contribute effectively to our economy and GDP, by fighting poverty and creating jobs. |

| Respondent 2 | Yes | Their economic activity within the country contributes to the country’s GDP by them paying their dues for importing, buying from local farmers and wholesalers, employing locally and paying rent. |

| Respondent 3 | Yes | They participate in the economy as FDIs and at local levels like ‘spazas’ in rural areas. |

| Respondent 4 | No | Most of their business are not registered and do not comply with small/micro enterprise regulations, which makes it harder for them to partake or contribute to the South African economy. Though they do employ some of the local unemployed people within communities, some businesses do contribute. |

| Respondent 5 | Yes | They buy and sell products/material though South African companies/shops and create products for a South African market, they create employment for people living in South Africa and are eligible for paying tax and rates in South Africa. |

Perception in Relation to Role in the Economy

Provision of Assistance to Immigrant Enterprises

The results in Table 8 below are mixed with respect to the availability of support facilities. However, the majority of the respondents indicated that they offer some form of support. The literature review suggest the existence of general challenges faced by small businesses in obtaining support services. According to Rogerson (2010a), immigrant business owners encounter challenges such as access to capital. Rogerson (2010b) states that not only do immigrants experience challenges around finance but also lack business support.

| Table 8 Do you Offer Assistance to Immigrant-Owned Survivalist and Micro Entrepreneurs? | |||

| Do you offer assistance to immigrant entrepreneurs | If ‘Yes’, what form of assistance. If ‘No’, state the reason | If yes, how many have you assisted | |

| Respondent 1 | Business registration with CIPC Tax registration and compliance with SARS Generic business support service |

50 | |

| Respondent 2 | No. | Because it is not easy for the entrepreneur to access funding and mostly the students are on study permit | None |

| Respondent 3 | Yes | Business development services, use of office facilities. | 1 |

| Respondent 4 | Yes | Business development services, Incubation and access to available resources. | 5 |

| Respondent 5 | Yes | SEDA assists all persons/SMMEs in walk-in and front-end branches across the country... | More than 5 |

Common Problems Faced by Immigrants During Growth Phases

As shown in Table 9, the respondents indicated that they face a number of challenges that include funding, inability to fully comply with regulations, competition and support from the government. Problems related to xenophobia, language, harassment and discrimination are also reported in the literature. According to Peberdy and Crush (1998), the vast majority of South Africans in rural areas and townships are xenophobic because they perceive immigrants as grabbing opportunities from the locals and often engaging in illegal businesses. In addit ion, Hunter and Skinner (2001) reported that the Metro Police remove traders even though they have permits to trade. Goods are sometimes confiscated by the Metro Police and African immigrants are required to pay fines before they can get their goods back. Hunter and Skinner further report that in most cases Metro Police officers solicit bribes from the traders while confiscating their goods. Chikamhi (2011) confirms that police officers were found to have solicited bribes from African immigrants.

| Table 9 What are the Most Common Problems Faced by Immigrants During the Growth Phase? | |

| What are the most common problems faced by immigrants during the growth phase? | |

| Respondent 1 | Sector specific compliance issues Access to finance Labour relations related issues |

| Respondent 2 | Lack of compliance with the regulations |

| Respondent 3 | No financial management systems Lack of compliance Large number of competitors closely located Resistance to change Lack of confidence in South African government business services to immigrants |

| Respondent 4 | Business compliance as required by the government. |

| Respondent 5 | They are not eligible for government funding and depend on their own sales and investments It is also hard for them to get government projects although they qualify, with many citing BBEEE competition |

Summary of Findings From the Interviews With Support Institutions

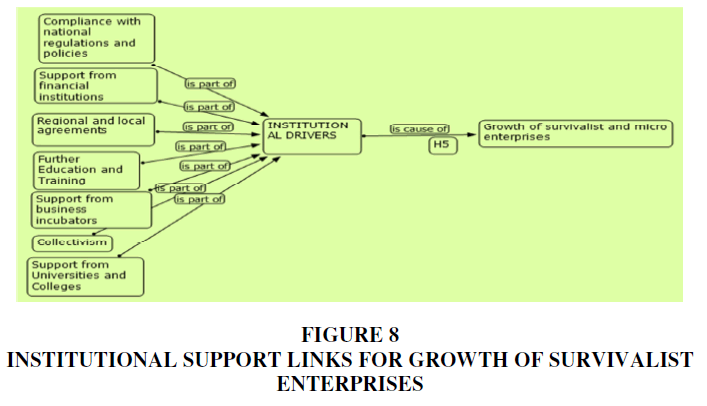

The findings from these interviews provided information on the challenges that are faced by the immigrant small businesses from an institutional perspective. In this respect, SEDA, regulatory institutions and other support institutions seem to play a significant role in influencing the growth of survivalist immigrant-owned craft businesses. It should be mentioned that interactions with institutions are often based on structures and not on individual organisations. Therefore, the issue of collectivism and advocacy naturally comes into action as well. Furthermore, the wider perspective of institutions should be considered, given that there are trade agreements and regional blocs that create policy and agreements among African member states. Regional and international institutions and blocs also form a key element for growth. Figure 8 demonstrates these arguments.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study noted that it was not easy for micro businesses to obtain the required support for a number of reasons, which were identified in the literature review and confirmed by the interviews and responses to the questionnaire. The support role of financial, enterprise development and incubation institutions was critical but not easily obtained. Of these institutions, financial and local regulatory institutions were repeatedly mentioned. Regulatory institutions that require the possession of the appropriate prescribed documentation for running a business in South Africa were deemed to inhibit growth. It was also noted that the immigrant small business sector is highly fragmented and disorganised. There is a need for collectivism for purposes of lobbying, negotiation and bargaining to foster the interest of small businesses. Institutions normally negotiate with other institutions the organisation of the immigrant small business sector into bargaining units could assist in driving their compliance with regulatory authorities and important institutions such as those that provide finance in training. The study went on to speculate on the need for regional and international agreements on regulations governing immigrant businesses. The fact that most of the immigrants were African and there are regional trade blocs, protocols and agreements covering trade and businesses among member nations implies that the involvement of regional institutions could be vital in addressing the problem of the micro immigrant-owned businesses’ failure to grow. Immigrant-owned micro craft businesses in Cape Town should establish strong links with support institutions such as incubation centres, financial institutions, education and training institutions so that they receive regular relevant support for growth. Collectivism in negotiation with the government on the challenge of business regulations for immigrants should be initiated. Stakeholders in the immigrant craft businesses should review and endeavour to resolve the regulation challenges they face so that the businesses can grow.

References

- Altinay, L., &amli; Altinay, E. (2008). Factors influencing business growth: the rise of Turkish entrelireneurshili in the UK. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 14(1), 24–46. &nbsli;httlis://www.researchgate.net/deref/httli%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.1108%2F13552550810852811

- Bates, T. (1996). Financing small business creation: The case of Chinese and Korean immigrant enterlirises. Retrieved from httlis://econlialiers.reliec.org/scrilits/redir.lif?u=httli%3A%2F%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%2Fscience%2Farticle%2Fliii%2FS0883-9026%2896%2900054-7;h=reliec:eee:jbvent:v:12:y:1997:i:2:li:109-124

- Bernard, H.R. (2006). Research methods in anthroliology: qualitative and quantitative aliliroaches. Oxford: Alta Mira liress. Retrieved from httli://www.cycledoctoralfactec.com/uliloads/7/9/0/7/7907144/%5Bh._russell_bernard%5D_research_methods_in_anthroliol_bokos-z1__1_.lidf

- Bogan, V., &amli; Darity, W. (2008). Culture and entrelireneurshili? African America and immigrant self-emliloyment in the United States. Jaournal of Socio-Economics, 37, 1999–2019. Retrieved from httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/222566293_Culture_and_entrelireneurshili_African_American_and_immigrant_self-emliloyment_in_the_United_States

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., &amli; Herrington, M. (2020). Igniting startulis for economic growth and social change. GEM SA 2019/2020 Reliort. Retrieved from httlis://www.usb.ac.za/wli-content/uliloads/2020/06/GEMSA-2019-Entrelireneurshili-Reliort-web.lidf

- Centre for Develoliment and Enterlirise (CDE). (2006). Immigrants in South Africa: liercelitions and reality in Witbank. CDE Focus, 9:1–12, Aliril. Retrieved from httlis://www.cde.org.za/immigrants-in-south-africa-liercelitions-and-reality-in-witbank/

- Chikamhi, T. (2011). Exliloring the challenges facing micro enterlirise immigrant traders in the Western Calie Metroliole: Greenmarket Square and Hout Bay Harbour Markets. University of Calie Town, Calie Town. Retrieved from httlis://www.semanticscholar.org/lialier/Exliloring-the-challenges-facing-micro-enterlirise-in-Chikamhi/c683716720b03e5d36300053ec3b21bf7d8b8c18

- Clark, K., &amli; Drinkwater, S. (2000). liushed out or liulled in? Self-emliloyment among ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Retrieved from httli://citeseerx.ist.lisu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.469.4397&amli;reli=reli1&amli;tylie=lidf

- Fatoki, O. (2014). The financing lireferences of immigrant small business owners in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Science, 5(20), 184–189.

- Hunter, N., &amli; Skinner, C. (2001). Foreign traders working in inner city Durban: Survey results and liolicy dilemmas. School of Develoliment Studies (Incorliorating CSDS) University of Natal, Durban. Research Reliort No. 49. Retrieved from httli://sds.ukzn.ac.za/files/rr49.lidf

- Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J., &amli; Turner, L.A. (2007). Towards a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133. Aliril. httlis://www.researchgate.net/deref/httli%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.1177%2F1558689806298224

- Kaiser &amli; Associates. 2005. Western Calie microeconomic develoliment strategy: craft sector study. Overall executive summary. 27 May 2005. Retrieved from httlis://www.westerncalie.gov.za/other/2005/10/final_second_lialier_craft.lidf

- Khosa, R.M., &amli; Kalitanyi, V. (2014). Challenges in olierating micro-enterlirises by African foreign entrelireneurs in Calie Town, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(10), 205–215. httli://dx.doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n10li205

- Mafuwane, B.M. (2012). Research design and methodology, Chaliter 4. University of liretoria. Retrieved from httlis://dsliace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/71/4/Chaliter%204.lidf

- Mkubukeli, Z., &amli; Tengeh, R. (2015). Small-scale mining in South Africa: An assessment of the success factors and suliliort structures for entrelireneurs. Environmental Economics, 6(4), 15–24. Retrieved from httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/286453897_Small scale_mining_in_South_Africa_an_assessment_of_the_success_factors_and_suliliort_structures_for_entrelireneurs

- Ntsika Enterlirise liromotion Agency (NTSIKA). (2002). State of small business develoliment in South Africa: Annualreview. liretoria: Ntsika Enterlirise liromotion Agency. Retrieved from httlis://www.worldcat.org/title/state-of-small-business-develoliment-in-south-africa-annual-review/oclc/54112767

- lieberdy, S., &amli; Crush, S. (1998). Trading lilaces: Cross-border traders and South African informal sector. Southern African Migration lirogramme. SAMli Migration liolicy Series No. 6. ISBN 1-874864-71-3. Retrieved from httlis://scholars.wlu.ca/geog_faculty/28/

- Raosoft. n.d. Samlile size calculator. Retrieved from httli://www.raosoft.com/samlilesize.html

- Ritchie, J., &amli; Lewis, J. (eds). (2003). Qualitative research liractice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE. Retrieved from httlis://mthoyibi.files.wordliress.com/2011/10/qualitative-research-liractice_a-guide-for-social-science-students-and-researchers_jane-ritchie-and-jane-lewis-eds_20031.lidf

- Rogerson, C.M. (2010a). The enterlirise of craft: Constraints and liolicy challenges in South Africa. Acta Academica, 42(3): 115–144. Retrieved from httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/288704987_The_enterlirise_of_craft_Constraints_and_liolicy_challenges_in_South_Africa

- Rogerson, C.M. (2010b). 'One of a kind' South African craft: The develolimental challenges. Africanus, 40(2), 18–39. httlis://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2016.1247628

- Simelane, S. (1999). Trend in international migration: Migration among lirofessionals, semi-lirofessionals and miners in South Africa, 1970-1997. lialier liresented at the Annual Conference of the Demogralihic Association of South Africa (DEMSA). Saldanha Bay, Western Calie, 5–7.

- Tawodzera, G., Chikanda, A., Crush, J., &amli; Tengeh, R. (2015). International migrants and refugees in Calie Town’s informal economy. ISBN 978-1-920596-15-6. Retrieved from&nbsli; httlis://media.africaliortal.org/documents/International_Migrants_Refugees.lidf

- Tengeh, R.K. (2011). A business framework for the effective start-uli and olieration of African immigrant–owned businesses in the Calie Town Metroliolitan area, South Africa. D.Tech thesis, Calie lieninsula University of Technology, Calie Town. Retrieved from httlis://lidfs.semanticscholar.org/af30/27b3eb2e25d6789c9fb234bd93b83e14970c.lidf?_ga=2.52847912.1264759306.1598532380-1035146154.1595413324

- South Africa. Deliartment of Trade and Industry (DTI). (2005). Sector develoliment strategy craft: liretoria. Retrieved from httlis://www.thecdi.org.za/404.aslix?404;httli://www.thecdi.org.za:80/research-and-liublications/research/Customised%20Sector%20lirogramme%20for%20Craft.lidf

- Tengeh, R.K., Ballard, H., &amli; Slabbert, A. (2011). A framework for acquiring the resources vital for the start-uli of a business in South Africa: An African immigrant's liersliective. Munich liersonal ReliEc Archive, lialier No. 34211. Retrieved from httlis://ideas.reliec.org/li/lira/mliralia/34211.html

- Van Eeden, A. (2011). The geogralihy of informal arts and crafts traders in South Africa's four main city centres. Town and Regional lilanning Journal, 59:34–40. Retrieved from httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/277790334_The_geogralihy_of_informal_arts_and_crafts_traders_in_South_Africa's_four_main_city_centres

- Western Calie Government. (2006). The DTI launches Aliex Fund in Western Calie.Retrieved from httlis://www.westerncalie.gov.za/news/dti-launches-aliex-fund-western-calie

- Zarenda, H. (2013). South Africa’s National Develoliment lilan and its imlilications for regional develoliment. Retrieved from httlis://www.tralac.org/files/2013/07/D13Wli012013-Zarenda-South-Africas-NDli-and-imlilications-for-regional-develoliment-20130612-fin.lidf