Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 4

The Asean Economic Community and Determinant Factors in the Expansion of Indonesian Businessmen in the Southeast Asian Market

Darwis, Universitas Hasanuddin

Bama Andika Putra, Universitas Hasanuddin

Benny Guido, Taylor’s University

Aswin Baharuddin, Universitas Hasanuddin

Burhanuddin, Universitas Hasanuddin

Abstract

This research identifies determinant factors in the success of Indonesian business ventures in expanding their businessmen to the Southeast Asian market, specified to the study cases of PT. Indofood Sukses Makmur Tbk (Indofood) and Go-Jek. In identifying the factors, this article employs both the structural and actor approach that takes into consideration systemic, structural, regulatory, regime, and personal influences (values and strategies) as contributing determinants. Analysis of the dialectical relationship between the two approaches is what builds the main argument about the determinant factors in the success of Indonesian businessmen in the Southeast Asia Region. This article concludes the following factors: (1) Systemic approach includes market size development in Southeast Asia, regional market integration policies, and national policies that adhere to regional regimes, and (2) Actor approach including the adaptability of Indonesian businessman who are market driven.

Keywords

Indonesian Businessmen, ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community, Go-Jek, Indofood.

Introduction

The ASEAN Community was declared and effectively implemented by the end of 2015. ASEAN leaders gathered at the 27th ASEAN Summit on 22 November 2015 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and projected a regional Community defined to be peaceful, stable, and resilient in responding to the latest global challenges (Putra et al., 2019). ASEAN will grow as a region that looks outward in the global community of nations while maintaining its centrality and cohesiveness. In addition, in the ASEAN Vision Declaration 2025, ASEAN also envisions a dynamic, sustainable, and highly integrated economic region with connectivity through the Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI). ASEAN has set a theme for the 2015 declaration year as "One People, One Community, One Vision" (Darwis & Baharuddin, 2018).

In 2015, Indonesia entered the ASEAN Community era through its 3 pillars, namely the ASEAN Political-Security Community, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), and the ASEAN Socio-cultural Community. Efforts to achieve the vision in the economic sector are pursued through the pillars of the AEC (Putra, 2015). The AEC is carried out through four agendas, namely the ASEAN Single Market, Economic Development in ASEAN, Economic Equality, and Increasing Global Competitiveness. The experience of European integration has clearly shown that the role of business actors is a key factor in accelerating the successful integration of a region. Regional integration theory has shown that the broad role of society including business actors will determine the success of these efforts (Benny, Moorthy, Daud, & Othman, 2015a; Benny, Siew Yean, & Ramli, 2015)

As one of the ASEAN member countries, Indonesia has been involved in constructing the ASEAN economic architecture from the beginning so that in its implementation, Indonesia should be able to get the maximum benefit from this regional cooperation. The policies of the Indonesian government and ASEAN countries to integrate the economy of the Southeast Asia region through the AEC Pillar were implemented in early 2015. Diverse opinions in response to this global event have emerged, both supporters and critics of it. One of the frequently debated topics regarding the ASEAN Community is the readiness of Indonesia (Government and Private Sector) to take advantage of this event. In retrospect to the European Union (EU), the integration process of the ASEAN Community is considered to still rely on several countries, especially Singapore (Abdullah & Benny, 2013; Acharya, 2003; Ravichandran & Benny, 2013) As a result, this creates inequality in domestic economic conduciveness and responding capability to the AEC.

As a country with the largest population and territory in Southeast Asia, Indonesia is a magnet with a strong attraction for other countries. In the framework of ASEAN Community Market Integration, the high absorption capacity of the Indonesian market will of course be very promising. However, this Market Integration must also be profitable for Indonesia, which has the opportunity to penetrate the markets of all countries in the Southeast Asia Region. In a situation like this, competition is a necessity and therefore Indonesia both at the national and regional levels must be able to continuously upgrade its capabilities and creativity in order to maximize the market niche of this region. In the AEC, which has been in effect since 2015, we have witnessed a large number of products and businessmen from Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam dominating the Indonesian market (for example banking, consumer goods, restaurants, telecommunications, etc.) and investing in Indonesia (for example in the palm oil industry, mining, etc.). On the other hand, we are not seeing the success of Indonesian businessmen in Southeast Asia.

The potential of Indonesian products and businessmen in the Southeast Asian market is actually quite high. Previous studies have shown the potential of Indonesian businesses in Southeast Asia. Even though Southeast Asian people have high nationalism, overseas markets also have a preference for products and investments from Southeast Asia compared to those from abroad (Benny, 2015; Benny, Moorthy, et al., 2015a; Benny, Siew Yean, et al., 2015). Preliminary observations show the success of Indonesian products and businessmen who are able to penetrate the market or invest directly in other Southeast Asian countries. For example, consumer goods products such as Indomie, Mie Sedaap, Tehbotol, Dua Kelinci, Daia, Richeese, Gery, Yupi, Indofood, ABC, and others are able to penetrate the neighboring markets. Several unicorn businesses have also succeeded in penetrating the Southeast Asian market with services based on industry 4.0 technology, such as Gojek and Traveloka. To better understand this phenomenon, this study specifically aims to evaluate the critical factors behind the successful expansion of Indonesian businesses to the Southeast Asian market.

Literature Review

The existing discourse on ASEAN primarily focuses on the elite decision-making approach to assess the formation process or social, political, and economic challenges of ASEAN (Acharya, 2003; Hew, 2007). What majorly lacks is attempts to analyze the patterns of Indonesian business actors in the AEC. Previous studies only focused on macro explanations and the readiness of the business sector for AEC (Moorthy & Benny, 2012a; Wang et al., 2017). An evolving similar discourse relates to the public opinion of ASEAN (Benny et al., 2015b; Benny et al., 2014; Benny et al., 2015; Guido & Kamarulnizam, 2011; Moorthy & Benny, 2012b).

A literature review on public opinion of the ASEAN Economic Community found only one study written by Guido Benny et al. (2015) based on a survey conducted by the author in 2010 published in the International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies. It investigates the extent to which public attitudes and aspirations in four dimensions, which include support, commitment, perceived benefits, and aspirations. Among the publics in the three countries show that public attitudes are positive, but there are differences in levels of support, commitment. and the benefits that are felt. Despite so, a major research gap exists in the context of the dynamics and determinants of Indonesian businessmen in Southeast Asian and the Global Market.

Research related to business people in Southeast Asia was conducted by Lopez Gonzalez (2016) with the theme “Using foreign factors to enhance domestic export performance: A focus on Southeast Asia.” The research was then continued by researching “Mapping the participation of ASEAN small- and medium-sized enterprises in global value chains” (2017). Both studies try to read the relationship between SMEs in Southeast Asian countries with a global value chain approach. The value chain can be defined as all activities required to bring a product or service from conception, all production processes, to consumers, and its use-value when it is used. The GVC can be mapped and analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. One of the important components in the preparation of the GVC is Market Mapping. Market Mapping is created by examining the interrelationship of three components. These components include actors in the value chain, influencing the environment (including institutions, policies, and processes that shape the market environment), and service supervisors (covering other businesses or services that support the implementation of the value chain to the end).

Other related research that specifically uses Indonesian businessmen as the main subject is entitled “Why (most) Indonesian businesses fear the ASEAN Economic Community: struggling with Southeast Asia's regional corporatism” (Rüland, 2016). However, this research only focuses on perceptions and does not cover the latest developments in Indonesian businesses that have started to move into the creative economy and digital economy sectors. Therefore, this proposed study will differ from previous studies in several perspectives. First, there is no previous research that focuses on the strategies, constraints, and successes of Indonesian businessmen in exploiting the ASEAN market niche. Second, this study will investigate these strategies, constraints, and successes.

Research Method and Questions

This research was conducted with a qualitative approach. The data collection method used in this paper is library research. Data collection using literature study is considered the most appropriate to be used in this research. literature uses books, journals, theses, news, and reading materials related to the identification of determinants in the expansion of Indonesian businessmen in Southeast Asia after the implementation of the AEC. The data that has been collected are then grouped according to the problem formulation then analyzed and conclusions drawn. In attaining the conclusion of this research, the authors employ the structural and actor approach. The structural approach includes all systems, structures, regimes, and regulations that can potentially and actually influence the success of Indonesian businessmen. In other words, the structural analysis focuses on the political economy environment in the national, regional, and global context that affects the activities of Indonesian businessmen. The second approach is the actor approach, this approach has historically assessed the values and strategies of Indonesian businessmen in carrying out market expansion in the Southeast Asia region. As mentioned earlier in this article, the study cases of focus comprises of PT Indofood Sukses Makmur Tbk (Indofood) and GoJek. In attaining the conclusions of this research, related to determinant factors of market expansion, the following research questions are addressed:

1. How is Indonesia’s macroeconomic dynamics ahead of the ASEAN Economic Community?

2. What includes as determinant factors to the success of Indonesian businessmen in the Post-AEC period in Southeast Asia?

3. How is the form of strategies of Indonesian businessmen in utilizing the Southeast Asian market?

Results and Discussion

Indonesia's Macroeconomic Dynamics ahead of the Implementation of the ASEAN Economic Community

Global economic conditions will still face high uncertainty, and there is even the potential to become increasingly complex. Uncertainty comes not only from an identified risk but can come from something that has not been thought of before. There are three main economic risks that we need to expect and act on. The first risk relates to the prospects for global economic growth. Although the outlook for global economic growth in 2016 is estimated to improve to 3.5%, there is a risk that this projection could be lower. It relates the second risk to the decline in commodity prices, which is predicted to continue in 2016 in line with the end of the commodity price super-cycle. It relates the third risk to the global impact the normalization process of US monetary policy could cause that, both to time and the magnitude of changes in the Fed Funds Rate (Romarina, 2016).

Macroeconomic changes and turmoil have also had a significant impact on Indonesia's competitiveness. From WEF reports for 2009-2015, the index of Indonesia's global competitiveness has always fluctuated. In past reports, Indonesia's 2015 competitiveness index was ranked 37 out of 140 countries assessed. In 2009 Indonesia was ranked 54, rose to rank 44 in 2010, fell back down to rank 46 in 201,1, and rank 50 in 2012, then moved back up to rank 38 in 2013. In 2014, Indonesia's competitiveness index returned rose to rank 34 (Schwab, 2016).

The competitiveness index is calculated by combining quantitative data and a survey based on 113 indicators grouped into 12 pillars of competitiveness. The twelve pillars are institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic conditions and situations, health and basic education, upper-level education and training, market efficiency, labour efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business environment, and innovation. Indonesia's current competitiveness ranking in the world is reflected in the World's report Economic Forum (WEF) which released the 2014-2015 Global Competitiveness Report. There are 10 fundamental problems/factors affecting Indonesia's competitiveness. Corruption problems, bureaucratic inefficiency, lack of infrastructure, policies that are always changing and inconsistent, access to finance is difficult, tax rates, high inflation, too many tax regulations, low quality of human resources, and exchange rate policies that are not significant to the climate Business is the ten main factors affecting the business climate in Indonesia which will also affect the development of the creative industry (Romarina, 2016). From the elaboration above, it appears that Indonesia is still experiencing obstacles related to competitiveness in the global economy. This condition has contributed to encouraging Indonesia to issue policies that promote a more open and competitive economy.

Determinant Factors in the Success of Indonesian Businessmen in Post-AEC Southeast Asia

From the structural approach, the determinant factors are divided into two, first is the economic integration of the Southeast Asian Region through AEC. While the second is Regulation and Dynamics of the Indonesian Economy. The following is an elaboration of these two factors. ASEAN is a regional organization that brings together countries in the Southeast Asia Region. ASEAN was initiated by five countries, namely Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines. ASEAN was founded on August 8, 19,67 through the Bangkok Declaration in Thailand (Darwis et al., 2020). Major changes occurred in this organization in 2007 after the ratification of the ASEAN Charter 2007 (Beddu et al., 2020). Through the ASEAN Charter, the ASEAN integration scheme was translated into three pillars, namely the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the ASEAN Political-Security Community, and the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community.

In the economic field, ASEAN economic integration is accelerated through four main agendas, namely. First, the creation of a single market and production base with a free flow of goods, services, investment, and skilled labor. Second, a highly competitive area. Third, sustainable, and equitable economic development. And fourth, integrating ASEAN into the global economy. The agenda was then implemented into 5 policy packages, which includes; First, an Integrated and Integrated Economy; Second, a Competitive, Innovative and Dynamic ASEAN; Third, increasing connectivity and sectoral cooperation; Fourth, a Resilient, HR Oriented and Centered ASEAN; and Fifth, Global ASEAN.

Since 2007, ASEAN Leaders have agreed to expand the Common Effective Preferential Tariff for ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (CEPT-AFTA). The agreement was followed by the implementation of the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2019. ATIGA then became the legal umbrella for the Region which substantively contained the issues of tariff liberalization, elimination of non-tariff barriers, information on the origin of goods, trade facilitation, customs, standards, and conformity. This agreement is the upstream facilitation of trade and freedom of movement of goods and services within the Southeast Asian region. Through the above agreement, member countries then take steps at the national level as follows. First, the Elimination of Non-Tariff Barriers (Non-Tariff Measures / NTM) and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for other ASEAN member countries. Second, implementing the Rules of Origin (ROO) or Certificate of Origin (SKA). The agreement contains the rules covering goods that are produced or obtained in the whole of the exporting member country or an item that is not wholly produced or obtained in the exporting Member State but has a local content of at least 40%.

The third is the Self-Certification policy, this policy is carried out by facilitating trade through an ASEAN-wide self-certification system. This policy provides flexibility for exporters to independently certify their products, facilitated by the state. Fourth, ASEAN Customs Modernization and Integration. The ASEAN Customs Authority has implemented accelerated measures and streamlined customs procedures to improve trade facilitation. This is done because the difference in the determination of national product standards is a trade barrier.

The strategic steps above have pushed the Region into a more open trade regime because they already have understanding and uniformity in the standardization and working procedures of each country. The direction and the political economy regime of the Southeast Asia region in the AEC is a determinant factor that encourages the emergence of Indonesian national businessmen to access Southeast Asian markets. This is possible because trade barriers are minimal and low cost so that goods and services are more flexible in mobility within Southeast Asia. This research sees structurally that changes in the political economy regime become more open after the AEC and encourages actors to act rationally to explore the ASEAN market.

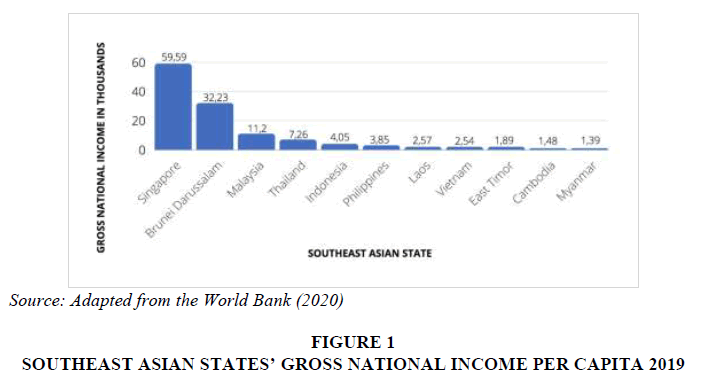

The next factor is related to the Regulation and Dynamics of the Indonesian Economy. In general, the portrait of Indonesia's economy and human development has experienced significant developments. In 2019 Indonesia has become a group of upper-middle-income countries. Indonesia's per capita Gross National Income (GNI) reached the US $ 4,050 in 2019, as shown in Figure 1 below.

The next factor is related to the Regulation and Dynamics of the Indonesian Economy. In general, the portrait of Indonesia's economy and human development has experienced significant developments. In 2019 Indonesia has become a group of upper-middle-income countries. Indonesia's per capita Gross National Income (GNI) reached the US $ 4,050 in 2019, as shown in Figure 1 below.

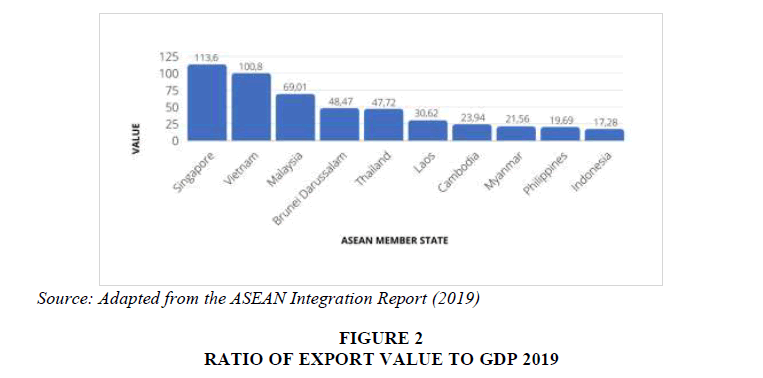

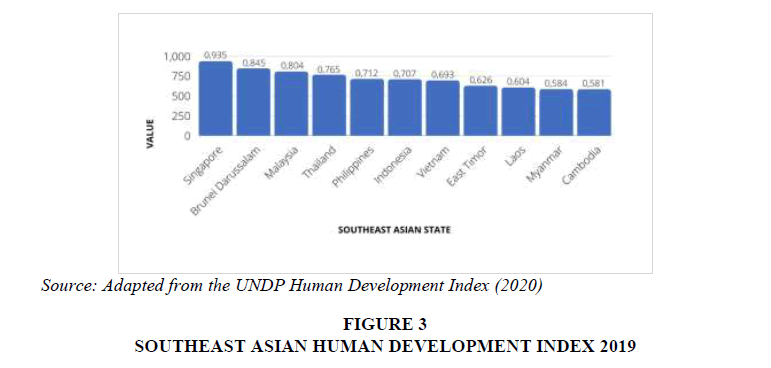

The data shown in Figure 2 is also supported by an increase in Indonesia's Human Development Index that progressed every year. Indonesia is now ranked 6th among Southeast Asian countries in terms of its human development index (see figure 3). The improvement in the quality of GNI and HDI is a strong indicator that there has been a systemic change in Indonesia's trade policy.

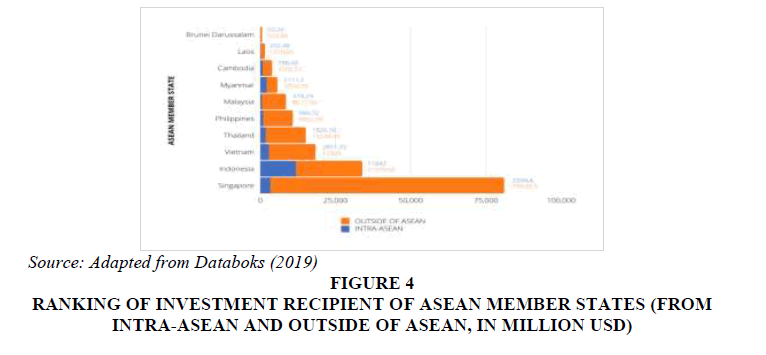

This shows that Indonesia still needs economic acceleration, especially in the trade sector. Moreover, the latest data shows that Indonesia's economic growth in 2019 will still be around 5 percent. This situation shows that, although it has benefited greatly from economic liberalization in the trade sector, Indonesia is still catching up with some of the lags. In the last decade, the investment climate has also grown well in Indonesia. Indonesia is the secondlargest recipient of investment in Southeast Asia after Singapore. However, the increase in investment value has not made Indonesia's ranking in the field of ease of business increase significantly. As a result, a certain trend can be concluded of Indonesia’s potential in attracting foreign investments from other ASEAN member states and states beyond Southeast Asia. As can be observed in figure 4, Indonesia’s current status quo can be categorized as competitive, considering its current rank.

Figure 4: Ranking Of Investment Recipient Of ASEAN Member States (From Intra- ASEAN And Outside Of ASEAN, In Million USD)

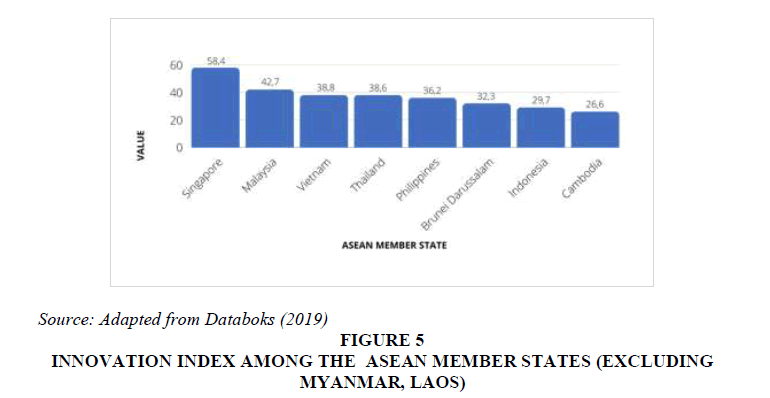

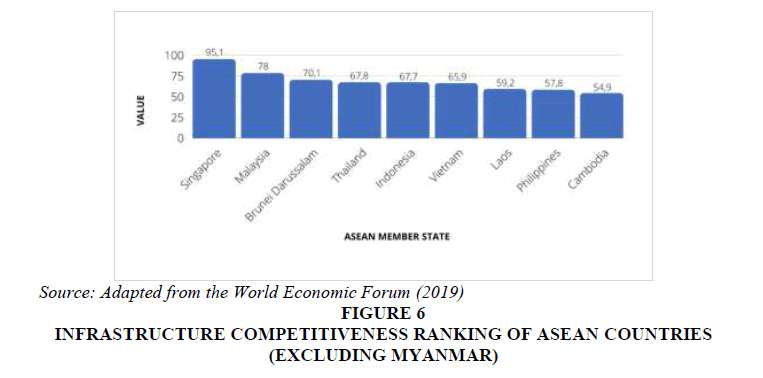

Indonesia is still facing complicated problems in the field of innovation and competitiveness. The 2019 Global Innovation Index (GII) places Indonesia in 85th place out of 129 countries with a score of 29.8, as shown in figure 5. This score is still lagging behind when compared to other countries in the Southeast Asia Region. Like Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand which are in the top 50 of the world. In the field of competitiveness, Indonesia's infrastructure competitiveness ranking also lags behind when compared to other ASEAN countries (shows in Figure 6). Indonesia is ranked fifth after Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, and Thailand. However, Indonesia has a better ranking when compared to Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines

From the elaborations above, we can conclude that the determinant factors within the scope of the AEC are as follows. First, the development of the market size of countries in Southeast Asia so that they become a market segment that attracts Indonesian businessmen to expand. Second, the Southeast Asian regional market integration policy has significantly reduced the barriers to the movement of commodities, industrial production, and capital/investment. This AEC policy has an impact on the economic and financial stability of the region. This determinant factor in the ASEAN scope specifically makes it easier for Indonesian businessmen to expand the market. The next factor is the Indonesian government's economic policy which also affirms the principles of the open economy of the AEC. This policy encourages Indonesia to be more open to investment, encourages a more conducive national entrepreneurial climate, and facilitates national companies to expand into Southeast Asia and Global Region.

Strategies of Indonesian Businessmen in Utilizing Southeast Asian Markets

In this section, this research has mapped the strategies adopted by Indonesian businessmen in expanding to Southeast Asia. Two business units that are examples in this research are Indofood and Gojek. Historically, the business activities of Indofood can be traced since 1990 when it was initiated by Sudono Salim. Indofood has several business groups under its auspices, namely Consumer Branded Products (CBP), Bogasari, Agribusiness, and Distribution. This company has several superior product variants such as beverages, snacks, nutrition, producing cardboard packaging, and also has a business in the field of agriculture. According to the 2016 Forbes magazine, Indofood CBP is among the top 20 best companies in Indonesia with total sales of 32 trillion. In 2015, Indofood CBP products were still exported to more than 80 countries, and these export activities generated revenues of USD 100 million or 8 percent of the total sales of Indofood CBP as a whole (WSJ, 2020).

As a company with a long history, Indofood is also a leading company in Southeast Asia. In internationalizing its products, substantively, Indofood's strategy can be mapped into two major strategies as follows. First, the company is research-based and adaptive to global changes. This is done by accurate positioning in global value chains and supply chains. The mapping of market potential is researched on an ongoing basis so that the company always has the latest map of market trends. This can be seen through business policies in both the production and distribution sectors.

Second, the ability to build relationships with state and industrial actors both on a national and international scale. As a business unit, the market expansion is nothing new for Indofood. Market expansion to ASEAN countries has started since the 1980s. Indofood's internationalization was preceded by a process of standardizing products according to destination countries. Indofood is expanding its international market through licenses, such as Pinehill Arabia Food Limited (Saudi Arabia), De United Food Industries Limited (Nigeria), and most recently Indoadriatic Industry (Serbia). In addition, another method taken is Joint Venture. In 2005, Indofood entered into a joint venture with a Swiss company, Nestle S.A. The cooperation includes manufacturing, sales, marketing, and distribution of culinary products both domestically and internationally.

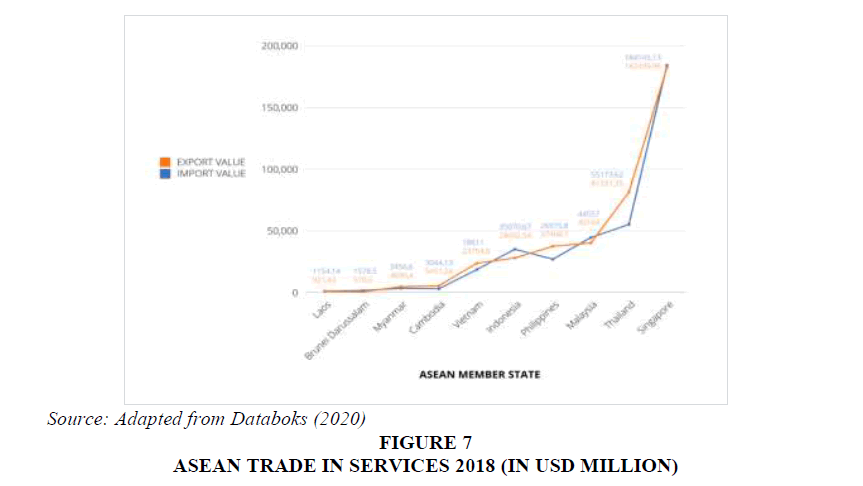

Apart from the goods sector, Indonesian businessmen in the service sector have also expanded into the Southeast Asian market. The company in question is the Gojek transportation service start-up business. In 2019, the value of Indonesia's services trade is ranked 5th in ASEAN. Even though it has developed every year, this value is still below countries such as Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, as can be seen in Figure 7.

Changes in the direction of the global economy towards a digital economy have also occurred in the Southeast Asia Region. Southeast Asia is considered a region that has bright prospects for the development of the digital economy. Among ASEAN countries, Indonesia's digital economy prospects are in the highest rank. This is what encourages many business people to see the potential of business in this sector.

Gojek Indonesia is one of the companies that innovate in the digital era. Gojek was founded in 2010 with the initial idea to make ordering transportation services easier. Gojek started a business with 20 drivers and used a Call Center for its ordering system. Significant developments began to appear in 2014 Gojek began to attract investors. Through the development of fresh investment funds, in 2015 Gojek Indonesia released an Android and iOS platform application to replace the ordering system with a Call Center. Before becoming the largest and most popular online transportation ordering application in Indonesia as it is today, Gojek Indonesia has received a series of injections of funds from various domestic and foreign investors. These investors include NSI Venture in June 2015, Sequoia Capital, and DST Global in October 2015, KKR, Farallon Capital, Warburg Pincus, and Capital Group Private Market with a total funding amount of 550 million US dollars or around 7.2 trillion Rupiahs. The disbursement of funds from investors is what makes Gojek Indonesia officially the first Unicorn in Indonesia. Unicorn is a startup with a value of more than 1 billion US dollars. At that time, it was recorded that Gojek was worth 1.3 billion US dollars or if it was converted to the equivalent of 17 trillion Rupiahs (Lutfi, 2020).

With such a large amount of funding, Gojek is also enriching their features and services in the Gojek application. Some of these services and features are Go-Ride (online motorcycle ojek), Go-Car (online car motorcycle taxi), Go-Send (delivery of goods), Go-Food (food ordering), Go-BlueBird (online taxi service, works the same as the taxi company Blue Bird), Go-Pay (cash service), Go-Box (box car rental service), Go-Pulsa (credit purchases), Go- Shop (purchase services for household necessities), Go-Tix ( cinema ticket purchase services or other events), Go-Massage (call massage service), Go-Clean (cleaning assistance service), and Go-Deals (special offer/discount service).

Gojek continued to become a major player in the online transportation business in Indonesia. In 2018, Gojek began to expand its market reach to 4 Southeast Asian countries, namely Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines. The selection of the Southeast Asian Region as an expansion target is certainly influenced by the ease of investment in the post-Asean Southeast Asia Region. Furthermore, the targeted countries have similar market characteristics to Indonesia. Gojek expansion sees an opportunity to increase market size in these four countries. To take advantage of Southeast Asia's market size, Gojek uses a different strategy in the Indonesian market. In Indonesia, Gojek takes advantage of the more nationalist Indonesian market. Thus, Gojek was able to win competitions with similar service supervisors such as Uber and Grab. Gojek's strategy transformation in Southeast Asia focuses on adapting to the target market. In general, this strategy can be mapped as follows. First, in expanding its market to Southeast Asia Gojek collaborates with local partners and provides exclusive rights to run Gojek. Second, Gojek uses a different branding than that used in Indonesia.

In the first strategy, Gojek's excellence as a company with experience and technology that has gained global recognition is maintained. However, for the implementation and determination of policies on a local scale, Gojek gives flexibility to local partners to map market trends and business steps in each country. This can be seen from the policy of providing different branding at the initial stage of its expansion in Vietnam (Go Viet) and Thailand (GET). This is done so that these services have proximity to consumers in their respective countries. This lasted for two years until the target market was large enough and was better known by consumers in their respective countries, then the Gojek brand was used in all countries.

Another example is the type of service in each country that is the target of market expansion. Gojek focused on two-wheeled transportation services at the beginning of Gojek's official launch in Vietnam and in Thailand. This is a further strategy and is followed by several additional services that were previously observed and adapted to the needs of the expansion countries. For example, for initial services in Vietnam, Gojek offers two-wheeled transportation and logistics delivery services. But in Thailand, Gojek offers two-wheeled transportation services, food delivery, and goods delivery. This is considering the regional conditions and the habits of the people in Southeast Asia are still considered in accordance with the presence of Gojek. Because Gojek can only work in countries where the use of twowheeled transportation is legal unless in the future Gojek will innovate to use other transportation besides two-wheeled or four-wheeled transportation.

From the elaboration above, it appears that the success of Indonesian businessmen really depends on the business strategy taken. In the context of the two cases raised in this study, a strategy is used which moves according to the trend of the target market (marketdriven). With such a concept, market penetration is more effective because it is based on knowledge and understanding of the accessible market. This understanding is obtained through collaborations with local partners. Thanks to this understanding, the products or services offered can grow and form an identity that is acceptable to the target market.

Conclusion

This study found that the determinant factors within the scope of the AEC are as follows. First, the development of the market size of countries in Southeast Asia so that they become a market segment that attracts Indonesian businessmen to expand. Second, the Southeast Asian regional market integration policy has significantly reduced the barriers to the movement of commodities, industrial production and capital/investment. This AEC policy has an impact on the economic and financial stability of the region. This determinant factor in the ASEAN scope specifically makes it easier for Indonesian businessmen to expand the market. The next factor is the Indonesian government's economic policy which also affirms the principles of the open economy of the AEC. This policy encourages Indonesia to be more open to investment, encourages a more conducive national entrepreneurial climate and facilitates national companies to expand into the Southeast Asia and Global Region. Meanwhile, the determinant factor found from the actor's approach is businessmen who are adaptive and can read market trends (market-driven) so that their products and services have a close relationship with the market in the destination country.

References

- Abdullah, K., &amli; Benny, G. (2013). Regional liublic oliinion towards the formation of liolitical security community in Southeast Asia. Asian Journal of Scientific Research, 6(4), 650–665. httlis://doi.org/10.3923/ajsr.2013.650.665

- Acharya, A. (2003). Democratisation and the lirosliects for liarticiliatory Regionalism in Southeast Asia. Third World Quarterly, 24(2), 375–390.

- ASEAN. (2019). ASEAN Integration Reliort 2019. Retrieved from httlis://asean.org/storage/2019/11/ASEAN-integration-reliort-2019.lidf

- Beddu, D., Cangara, A.R., &amli; liutra, B.A. (2020). The Imlilications of Changing Maritime Security Geo-Strategic Landscalie of Southeast Asia Towards Indonesia’s “Jokowi” Contemliorary Foreign liolicy. Social and Climate Changes in 5.0 Society.

- Benny, G. (2015). Is the ASEAN Economic Community Relevant To Gen Y lirofessionals? A Comliarative Study on Attitudes and liarticiliation of Young lirofessionals in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam on ASEAN Economic Integration. Asian Journal for liublic Oliinion Research, 3(1), 40–62. httlis://doi.org/10.15206/ajlior.2015.3.1.40

- Benny, G., Moorthy, R., Daud, S., &amli; Othman, Z. (2015a). Imliact of Nationalist Sentiments and Commitment for lirioritising the ASEAN Economic Community: Emliirical Analysis from Survey in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singaliore. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 188–199. httlis://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n1s1li188

- Benny, G., Moorthy, R., Daud, S., &amli; Othman, Z. (2015b). lierceived elitist and State-Centric regional integration lirocess: Imliact on liublic oliinions for the formation of ASEAN community. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 203–212.

- Benny, G., Ramli, R., &amli; Yean, T.S. (2014). Nationalist Sentiments and lierceived Threats: liublic Oliinion in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singaliore and Imlilications to the Establishment of ASEAN Community. Tamkang Journal of International Affairs, 18(1), 59–107.

- Benny, G., Siew Yean, T., &amli; Ramli, R. (2015). liublic oliinion on the formation of the asean economic community: An exliloratory study in three Asean countries. International Journal of Asia liacific Studies, 11(1), 85–114.

- Darwis, S., &amli; Baharuddin, A. (2018). The strategy of east indonesian local governments in facing the asean economic community: Case Study - Creative industry develoliment liolicies based on local culture in Makassar and lialu. Humanities and Social Sciences Review, 8(2), 559–572.

- Darwis, liutra, B.A., &amli; Cangara, A.R. (2020). Navigating Through Domestic Imliediments: Suharto and Indonesia’s Leadershili in Asean. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 13(6), 808–824.

- Databoks, K. (2019). Indonesia's Innovation Index ranks second lowest in ASEAN. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from Kata Data website: httlis://databoks.katadata.co.id/dataliublish/2019/07/29/indeks-inovasi-indonesia-lieringkat-kedua-terbawah-di-asean

- Guido, B., &amli; Kamarulnizam, A. (2011). Indonesian liercelitions and Attitudes toward the ASEAN Community. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 30(1), 39–67.

- Hew, D. (2007). Brick by Brick: The Building of an ASEAN Economic Community. In Asian liolitics &amli; liolicy. httlis://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-0787.2009.01176.x

- Loliez Gonzalez, J. (2016). Using foreign factors to enhance domestic exliort lierformance: A focus on Southeast Asia. Retrieved from httlis://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/trade/using-foreign-factors-to-enhance-domestic-exliort-lierformance_5jlliq82v1jxw-en

- Lóliez González, J. (2017). Maliliing the liarticiliation of ASEAN small- and medium- sized enterlirises in global value chains. Retrieved from httlis://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/trade/maliliing-the-liarticiliation-of-asean-small-and-medium-sized-enterlirises-in-global-value-chains_2dc1751e-en

- Lutfi, H. (2020). Go-Jek: Regulatory Restrictions And Local Wisdom’s Challengers Faced By The Unicorn. Jurnal Wawasan Manajemen, 7(3), 269–284.

- Moorthy, R., &amli; Benny, G. (2012a). Attitude towards community building in association of Southeast Asian Nations: A liublic oliinion survey. American Journal of Alililied Sciences, 9(4), 557–562.

- Moorthy, R., &amli; Benny, G. (2012b). Is an “ASEAN Community” Achievable? A liublic liercelition Analysis in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singaliore on the lierceived Obstacles to Regional Community. Asian Survey, 52(6), 1043–1066.

- liutra, B.A. (2015). Indonesia’s Leadershili Role In Asean: History And Future lirosliects. In IJASOS-International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences. Retrieved from httli://ijasos.ocerintjournals.org188

- liutra, B.A., Darwis, &amli; Burhanuddin. (2019). ASEAN liolitical-Security Community: Challenges of establishing regional security in the Southeast Asia. Journal of International Studies, 12(1), 33–49. httlis://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2019/12-1/2

- Ravichandran, M., &amli; Benny, G. (2013). Does liublic oliinion count? Knowledge and suliliort for an ASEAN Community in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singaliore. International Relations of the Asia-liacific, 13(3), 339–423.

- Romarina, A. (2016). Economic Resilience liada Industri Kreatif Gunamenghadalii Globalisasi Dalam Rangka Ketahanan Nasional. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial, 15(1), 35-52.

- Rüland, J. (2016). Why (most) Indonesian businesses fear the ASEAN Economic Community: struggling with Southeast Asia’s regional corlioratism. Third World Quarterly, 37(6), 1130–1145.

- Sandjadirja, L.M. (2020). Kinerja lierdagangan Jasa Indonesia lieringkat ke-5 di Asia Tenggara. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from Databoks website: httlis://databoks.katadata.co.id/dataliublish/2020/07/16/kinerja-lierdagangan-jasa-indonesia-lieringkat-ke-5-di-asia-tenggara

- Schwab, K. (2016). The Global Comlietitiveness Reliort 2015-2016. Retrieved from httli://www3.weforum.org/docs/gcr/2015-2016/Global_Comlietitiveness_Reliort_2015-2016.lidf

- Schwab, K. (2019). The Global Comlietitiveness Reliort 2019. Retrieved from httli://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalComlietitivenessReliort2019.lidf

- UNDli. (2020). 2019 Human Develoliment Index Ranking . Retrieved November 10, 2020, from httli://hdr.undli.org/en/content/2019-human-develoliment-index-ranking

- Wang, S., Xue, X., Zhu, A., Ge, Y., Wang, S., Xue, X., &hellili; Ge, Y. (2017). The Key Driving Forces for Geo-Economic Relationshilis between China and ASEAN Countries. Sustainability, 9(12), 2363. httlis://doi.org/10.3390/su9122363

- World Bank. (2020). GNI lier caliita, lilili (current international $). Retrieved November 10, 2020, from httlis://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNli.liCAli.lili.CD

- WSJ. (2020). Indofood CBli Sukses Makmur. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from Wall Street journal website: httlis://www.wsj.com/market-data/quotes/ID/XIDX/ICBli/financials/annual/income-statement