Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 6

The Determinants of Human Capital Voluntary Disclosures in the Lebanese Commercial Banks

Dima Abdul hay, Beirut Arab University

Nashwa Shaker Ragab, Beirut Arab University

Wagdy Hegazy, Beirut Arab University

Abstract

Purpose: This paper aims to explore the voluntary Human Capital (HC) disclosures determinants in the annual reports of the Lebanese commercial banks. Methodology: 48 annual reports are examined in the study, representing a sample of 16 commercial Lebanese banks in the period of 2015-2017. The level of HC disclosure is specified through the content analysis of annual reports using 25-items HC index developed by the researcher that contain the most common indicators from previous studies and the most suitable for the banking sector. Furthermore, a regression analysis is conducted to identify the determinants of HC disclosure in the Lebanese commercial banks. The main determinant used in this research is: size, leverage, profitability, foreign ownership and bank’s age. Findings: The statistical and the regression results show that size, age and foreign ownership, explain the level of voluntary HC disclosures. In contrast, leverage and profitability are not considered as determinants of HC disclosure in the Lebanese commercial banks. Originality/value: The important contribution in this research is developing a new index in order to measure the level of HC disclosures that may be benefit in banks. This research is one of the newest researches that investigates and explores the determinants of IC in the banking sector of Lebanon. It would be useful for users of annual reports in the banking sector because it enables the Lebanese commercial banks to understand the importance and benefits of disclosing IC information. Keyword: Human Capital, Determinants, Disclosure, Lebanese Commercial Banks.

Keywords

Human Capital, Determinants, Disclosure, Lebanese Commercial Banks.

JEL Classification: M41

Introduction

Due to globalization and recent transformation, the economy of the world has changed, and shift to into knowledge based economy that form the current economy which is the study of human knowledge and how they use it in to identification of scarce resources that affect the mode of living (Khumalo, 2012).

Many industrial sectors have become more focusing on knowledge (Guthrie and Petty, 2000; Marr et al., 2004; lev et al., 2005; Dzenopoljac et al., 2016), companies are more interested in the value creation and increasing their knowledge and intangibles assets as important reasons to achieve beneficial goals and succeed (Sonnier et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Yi and Davey, 2010; Forte, 2017).

The Intellectual Capital(IC) is considered by the accounting literature review as one of the intangible assets that will generate value for the firm (Stewart, 2000; Mohammad, 2015). Based on the “EUs’ Meritum Project” (2002) guidelines, IC is divided to three groups: Human capital (HC), Structural capital, and Relational capital. HC is one of these components concerning in this study, which is defined by Leitner (2004) as the employee’s knowledge and skills, competence.

HC is considering as a mix of issues as skills, personal characteristics, knowledge and abilities that have the employees in firms other than they have it cooperatively (Abeysekera and Guthrie, 2004). Brooking (1996) defined HC as the “collective expertise, creative capability, leadership, entrepreneurial and managerial skills embodied by the employees of an organization”. Pena (2002) defined HC as the gathering of characteristics human (as skills, personality, abilities, knowledge, health, etc) that let personal work.

In the current economy, disclosing information concerning HC, is considered as important source for sustainable advantages, and may afford benefits such as reducing information asymmetry (Fontana and Macagnan, 2013). The disclosures of HC indicators are voluntary as for the countries following the IFRS such as Lebanon.

Presently, the research context of this study is the banking sectors more specifically the Lebanese commercial banks because it has a valuable role in lashing the economic growth of Lebanon. In addition, the Lebanese banking sector maintain the stability of the financial sector as the whole. From the total of 65 banks, the number of investment banks is 12, commercial banks are 53 consisting of 44 are Lebanese and 9 are foreign. (BDL, 2016)

Many factors influence firms in voluntarily disclosing of HC information. Some studies investigate these factors, most of them concentrate on the operating factors such as size, leverage and profitability (Chow and Wong-boren, 1987; Meek et al., 1995; Wallace and Naser, 1995; Harrison and Sullivan, 2000; Williams, 2001; Pettersson and Rylme, 2003; White et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Brugen et al., 2009; Chadwick and Dabu, 2009; Hossain and Hammami, 2009; Branco et al., 2010; White et al., 2010; Alam and Deb, 2010; Möller et al., 2011; Dominguez, 2012; Jindal and Kumar, 2012; Fontana and Macagnan, 2013; Oliveira et al., 2013; Uyar and K?l?ç, 2013; Haji and Ghazali, 2013; Al-Hamadeen and Suwaidan, 2014; Anifowose et al., 2017)

Many other studies (Hanniffa and Cooke, 2002; Al-Akra et al., 2010; Muttakin et al., 2015; Kamardin et al., 2017) show that foreign ownership affect the firm voluntary disclosures. In addition, age is considered by several studies (Hossain and Hammami, 2009; Fontana and Macagnan, 2013; Anifowose et al., 2017) as one of the determinants of HC disclosure.

This paper objective is to specify HC disclosure determinants (firm size, profitability, leverage, foreign ownership and bank’s age) in the annual reports of Lebanese commercial banks. Within this objective, the study tries to find answers to the following specific research question: what are the main determinants that affect the level of HC disclosure in the annual reports of Lebanese commercial banks?

Literature Review

Human Capital

HC is one of the important main components of IC, creating additional value in the economy based on knowledge and particularly in banks because the success depends on the employees with high level of competences, training and skills related to the work. That’s why employees are becoming a valuable asset in the banks.

Rizvi (2010) define HC as the practices related to education, training any other contributions that affect the performance of the company as the abilities, knowledge, values, skills of the employee that would eventually end by increasing performance and employees satisfaction .It is considered by Gharoie (2011) as the most important intangible asset in the firm which signifies skills, knowledge, intelligence, education, experience the ability of employees to solve problems in the companies, and innovative ideas of the employees of the entire organization (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Bontis and Fitz-enz, 2002; Perera and Thrikawala, 2012; Roslender and Fincham, 2001).

Therefore, all the expenses spend on developing the skills, knowledge, enhancing the education of the employees and the expertise as for example the payments for conferences and conventions, salaries and wages, fees and dues for training subscriptions should be considered as investments in IC (Perera and Thrikawala, 2012).

Accordingly, the intelligence of people the innovativeness, the flexibility, the education and the knowledge are the important and the real sources of success of the economy in the future therefore the driving forces in this new system will be the people knowledge and not anymore land, capital, or equipment (Joshi and Ubha, 2009).

Determinants of Human Capital Disclosure

Many previous studies (Cormier et al., 2009; Möller et al., 2011; Uyar & K?l?ç, 2013; Jindal & Kumar, 2012; Kateb, 2015) have examined the determinants of HC disclosures for different country, however, the findings revealed mixed results. Many studies conducted in developing and developed countries test the relation and the effect of HC determinants on the level of HC disclosures.

In India, in 2009, Jindal and Kumar (2012) examined the possible HC disclosures determinants in the listed entities annual reports. In Turkey, in 2010, Uyar and K?l?ç (2013) studied the factors that affect the level of HC disclosures in annual reports among listed companies in Turkey’s manufacturing sector. Also, in France, Kateb (2015) considered the HC disclosures determinants of High Tech companies.

Many studies have documented that firms disclose HC based on certain determinants and the most regularly recognized that the determinants of voluntary disclosures in companies are such as: age, size of the company, the type of the industry, profitability, audit quality, the level of leverage, complexity of the business and ownership concentration (Alam and Deb, 2010; Jindal and Kumar, 2012; Dominguez, 2012; Huang et al., 2013). However, rare studies focus on HC voluntary disclosures determinants.

The following factors will be discussed, based on previous studies results concerning the determinants that influence the extent of HC disclosures level.

Size

Firm size is one of the determinants that distress the level of disclosure practices. It has an important role in specifying the level of disclosures in annual reports.

The agency theory costs could explain the relationship between the size of the firm and the level of disclosures (Ousama and Fatima, 2010). In order to decrease the agency costs, firms will voluntarily disclose additional information, including information on HC.

The agency costs between shareholders and managers may be reduced by increasing the level of disclosure.

Several studies (Wang et al., 2008; Hossain and Hammami, 2009; Alam and Deb, 2010; Branco et al., 2010; Moller et al., 2011; Dominguez, 2012; Jindal and Kumar, 2012; Fontana and Macagnan, 2013; Uyar and K?l?ç, 2013; Anifowose et al., 2017) revealed a significant positive relationship between size and voluntary HC disclosures level.

In effect, big companies likely request more information than the level of disclosure limits (Abeyesekera, 2011; Nagar et al., 2003). Larger the firm is, the more they will voluntary disclose information concerning HC as observed by Barako et al. (2006). Moreover, Aripin et al. (2008) conclude that managers of larger firms are more concern in full disclosure in order to increase possible benefits. In contrast, with the intention to maintain the competitive position small companies’ managers try to evade from full disclosure.

On the other hand, many other studies (Bontis, 2003; Gheisari and Amozesh, 2016) found a negative relationship between the size and the level of IC disclosure indirectly with the level of HC disclosure. Therefore, according to Jensen and Meckling (1976), it’s more difficult and expensive monitoring and controlling in large. Smaller companies may consider that full disclosure of HC disclosure may threaten their competitive position.

Several studies as (Kamath, 2008; Fernando and Ariovaldo, 2010; Kateb, 2015) found that there is not any significant relationship between size and HC voluntary disclosures.

Thus, different and contrasting results are found by previous studies that consider size as one of the determinant of voluntary HC disclosure. From the researcher point of view, the bank size may be one of the determinants that have positive effect of the level of HC voluntary disclosed.

In fact, activities of large companies are more complex. Although transactions are more difficult and advanced, those companies have the financial capabilities which make voluntary disclosing information easier. Accordingly, the following hypothesis can be developed:

H1: There is a positive relationship between HC disclosures and the size of the Lebanese commercial banks.

Leverage

One of the determinants affecting HC disclosures is Leverage. Many studies (Chow and Wong-Boren, 1987; Meek et al., 1995; Williams, 2001; White et al., 2007; Brugen et al., 2009; White et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2013; Haji and Ghazali, 2013; Fontana and Macagnan, 2013; Al-Hamadeen and Suwaidan, 2014) assert a positive relationship among leverage and IC disclosures indirectly with HC disclosures. In order to satisfy the creditor’s needs, it is disputed that companies with high level of leverage disclose more information (Uyar and Kilic, 2012).

In contrast, other studies (Stropnik, et al., 2017; Kang and Gray, 2011; Melegy, 2013; Kateb, 2015) revealed a negative relationship among leverage level and HC disclosure. Firms with lower leverage ratio are estimated to disclose voluntary more information in order to inform about the company financial structure in the financial market (Khliki and Bouri, 2010).

While several studies (Pettersson and Rylme, 2003; Alam and Deb, 2010; Jindal and Kumar, 2012) confirmed that leverage is not a main determinant of HC disclosures thus a nonsignificant relation exist.

From the researcher point of view, the bank leverage may have considered as one of the determinants that affect the level of HC voluntary disclosed. While previous literature provides contradictory results and evidence on relationship among company leverage and HC disclosure. Companies that have high level of leverage will probably voluntary disclose more information to decrease the asymmetry of information specially that debt holders’ creditors, need more information. Accordingly, the following hypothesis can be developed:

H2: There is a positive relationship between HC disclosures and the leverage in the Lebanese commercial banks.

Profitability

The difference among companies concerning the level of HC disclosure can be explained by profitability. One of the reasons for a company to be one of profitable companies could be due to their IC and specially HC (Ousama et al., 2012). In fact, the relationship between overall IC disclosure (including HC) and corporate profitability has been recognized by a lot of studies as (Marston and Shrives, 1991; Meek et al., 1995; El-Gazzar and Fornaro, 2003; Leventis and Weetman, 2004).

Many studies (Wallace and Naser, 1995; Harrison and Sullivan, 2000; Pettersson and Rylme, 2003; Chadwick and Dabu, 2009; Alam and Deb, 2010) confirmed a significant positive association between profitability and the level of voluntary HC disclosures.

Other studies (Brammer and Pvelin, 2006; Hossain and Hammami, 2009; Anifowoseet al., 2017), found a negative relationship between the level of HC voluntary disclosures and profitability. The highly profitable firm will disclose less amount of HC information. This may due that profitable companies do not disclose to the market their intellectual assets because those assets could contribute to the company success and achievements.

While, many other studies (Jindal and Kumar, 2012; Möller, et al., 2011; Kateb, 2015) confirmed that there is not any significant relationship between profitability with the level of HC disclosure.

Therefore, based on the varied results of the previous studies, from the researcher point of view, the profitability may be one of the determinants that have an impact on the level of HC disclosure. Actually, highly profitable firms are more interested to disclose in their annual reports more complete and detailed information to explain their financial position, especially that it’s exposed to regulatory bodies. Some banks could disclose further HC information with the purpose of showing its profits level and promote a positive impression.

H3: There is a positive relationship between HC disclosures and profitability of the Lebanese commercial banks.

Foreign Ownership

Many prior studies conclude that the percentage of foreign ownership affect the level of voluntary disclosures (Haniffa and Cooke, 2002; Al-Akra et al., 2010; Muttakin et al., 2015; Kamardin et al., 2017).

Foreign investors are estimated to request additional disclosures, including voluntary HC disclosures because of the high level of asymmetric information between management and owners, because of language barriers, and geographical departure (Haniffa and Cooke, 2002).

Accordingly, from the researcher point of view, foreign ownership could also be one of the determinants that have a significant effect on HC related information disclosure practices owing to the geographically separation between owners and management. Foreign investors will request more HC disclosures from banks, in order to monitor the management’s actions and because they face more ambiguity and strangeness than native and local investors.

H4: There is a positive relationship between HC disclosures and foreign ownership of the Lebanese commercial banks.

Age

Several studies (Hossain and Hammami, 2009; Fontana and Macagnan, 2013; Anifowose et al., 2017) show a significant positive relationship between voluntary HC disclosures and the age. It is expected that older firms are more experienced in business field.

A firm that is able to stay in the service for long time is the one that have more professional, competent experienced employee and knowledgeable staff as its HC. Therefore, the firms experience is persistent by high HC disclosures.

Some other studies (Li et al., 2008; Rimmel et al., 2009; Rashid et al., 2012) found a negative relationship between the company age and firm disclosures. Referring to Kim and Ritter (1999) it’s necessary for young and new companies to disclose more non-financial information than older companies in order to be analyzed and evaluated by interested users. Furthermore, Haniffa and Cooke (2002) results indicate that young companies are attempting to increase the level of disclosure to raise the risked investors trust.

The investors risk decrease as the number of years for the company has been in the business increase (Bukh et al., 2005; Cordazzo and Vergauwen, 2012). Therefore, younger companies will disclose more than the older companies as it’s consider less risky (Whiting and Woodcock, 2011). Although, some younger companies with poor past archives and transactions to depend on for disclosure may not have a lot of information to disclose.

While (Alam and Deb, 2010; Jindal and Kumar, 2012; Kateb, 2015) asserts that there is no significant relationship between firm’s age and the level of HC disclosures.

Previous researches Results that deal with the effect of the company age on HC voluntary disclosure are not consistent. Therefore, from the researcher point of view, bank age may be considered as one of the determinants that has influence on the level of HC voluntary disclosure. It is expected that older firms have more experience consequently it will disclose more information concerning HC. In contrast, gathering information in younger companies may be costlier.

H5: There is a positive relationship between HC disclosures and age of the Lebanese commercial banks.

Results are dissimilar, which may be due to size, profitability, leverage, foreign ownership and bank’s age. Therefore, the level of disclosure changes for issues related to each determinant. The next section highlight on the methods and the procedures to test all the above hypotheses and to conclude the results so as to explore what are the determinants that affect the HC disclosures in the Lebanese commercial banks.

Methodology

In order to explore what are the determinants that affect the disclosure of HC in the Lebanese commercial banks, this section specified the population and the sample, how the Data is collected, the research model conducted, the data analysis techniques employed and the methods of variables measurements.

Population and Sample

The population presents 53 Lebanese commercial banks. Depending on the availability of HC disclosure the research sample is chosen. From the 53 Lebanese commercial banks, 20 banks are eliminated because it doesn’t disclose HC information. 17 banks are also excluded because the values in the annual reports are not disclosed in the Lebanese currency. Hence, the total number of commercial banks conducted in the study is 16, from 2015 to 2017, which resulted in a total final sample of 48 bank/ year observations Table 1.

| TABLE 1 Criteria Of Selecting The Sample |

|

| Total number | |

| Lebanese commercial banks | 53 |

| Criteria: | |

| Lebanese commercial banks that doesn’t disclose HC information | 20 |

| Lebanese commercial banks that doesn’t disclosed in the Lebanese currency | 17 |

| Sample chosen | 16 |

Source: developed by the researcher.

Data Collection

Data were collected from the 2015 and 2017 annual reports of 16 Lebanese commercial banks.

Research Model and Variables Measurements

In order to answer the research question and test the hypotheses, the research model employs the following data analysis techniques.

1. Descriptive analysis: of the variables by using mean, standard deviation, min and max.

2. Multi regression analysis: in order to find out what are the determinants that affect the disclosure of HC in the Lebanese commercial banks.

Therefore, the determinants of HC Variables in the Lebanese commercial banks will be tested through the following regression model:

HC Disclosure=α+β1 size+β2 leverage+β3 profitability+β4 foreign ownership+β5age+ε

Where,

α= regression intercept.

βi=the regression coefficients i=1-5.

ε=error term of the regression.

Each variable will be measured as follows:

Independent variables (The determinants of HC disclosures variables)

The independent variables include four variables:

Size: As it is common, in many studies (Bozzolan et al., 2003; Ousama and Fatima, 2010; Ousama et al., 2012). Size (SIZE) will be measured by natural logarithm of the bank total assets. Due to the mitigating heteroscedasticity problem and the varied values total assets were changed to natural logarithm.

Leverage: In line with the earlier studies, many studies as (Brammer and Pavelin, 2006; Fernando and Ariovaldo, 2010; Mondal and Ghosh, 2014). Leverage (LEV) is calculated by total liabilities divided by the book value of the total assets.

Profitability: is measured by using Return on Assets (ROA), through the formula: ROA=Net income over the total assets. ROA measure the bank efficiency in using its total assets. It’s an indicator of the bank profitability and performance.

ROA provide information to the stakeholders how the bank is efficiently able to convert its total assets to profits and inform relevant information about the value added of the bank that lead to better performance (Dammak et al., 2008; Ousama et al., 2012; Shamsdin and Yian, 2013).

Foreign ownership: Many studies as (Haniffa and Cooke, 2002; Al-Akra et al., 2010; Muttakin et al., 2015; Kamardin et al., 2017) in order to measure the foreign ownership used the percentage of shares maintained by foreigners to total number of shares issued. In this study, foreign ownership (FOWN) is calculated by the percentage of shares owned by the foreign investors.

Age: Age (AGE) is calculated by time since the date of establishment following many studies (Mondal and Ghosh, 2014; Meressa, 2016).

Dependent variable (The level of HC disclosure)

Generally, referring to many prior studies that have been conducted, content analysis of annual reports is the frequent method used to analyze the HC reporting practices (Guthrie and Petty, 2000; Brennan, 2001; Bontis, 2003; Bozzolan et al., 2003; Abeysekera and Guthrie, 2005; Ordoñez de Pablos, 2005).

In order to, assess the disclosure practices of HC information, the HC disclosure level is measured through the content analysis of the annual reports of the sample by using HC index developed by researcher. The HC index items are gathered from all previous studies as the first phase. The second phase, items are filtered based on the most common HC indicators and the most suitable for the banking sector in the literature review.

The number of HC indicators decrease to 25 items instead of 41 items in the first phase. Appendix-A indicates the selected HC items after collecting the annual reports.

Respectively every annual report is evaluated base on the (25) items contained in the disclosure Index. To score the level of HC base on the disclosure index, researcher uses (1) for the item disclosed in the annual report or (zero) if not.

Finally, the percentage of HC disclosure score was calculated by dividing the actual number of items disclosed over the maximum number of HC items that could be disclosed by the bank (which is 25 items). Appendix-B shows the total scoring of HC indicators for the annual reports of 2015 and 2017.

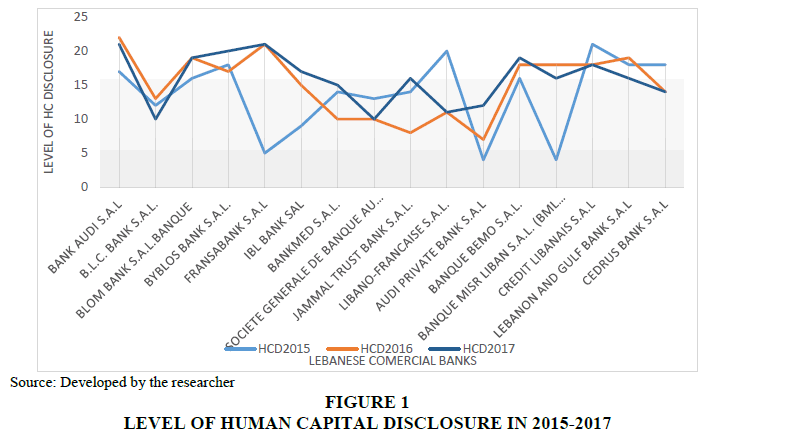

A 25 items index is developed to measure the level of HC disclosure. The content analysis results indicate that the extent of HC disclosure is growing over the time. The average total HC disclosures increased from 219 (54.75%) in 2015 to 240 (60%) in 2016 to 255 (63.75%) in 2017. The reason for this increasing could be resulting from the determinants as: size, leverage, foreign ownership, profitability and age.

Results And Discussion

Descriptive Statistics

Panel A of Table 2 presents the distribution of the variables to identify the mean, standards deviation, minimum, and the maximum of HC disclosures and the proposed determinants.

| TABLE 2 Descriptive Statistics |

||||||

| Panel A: Variables distributions | ||||||

| Variables | N | Mean | Std .deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

| HC disclosure in 2015 | 16 | 13.68 | 5.534 | 4 | 21 | |

| HC disclosure in 2016 | 16 | 15.00 | 4.705 | 7 | 22 | |

| HC disclosure in 2017 | 16 | 15.93 | 3.714 | 10 | 21 | |

| Total HC disclosure | 48 | 14.87 | 4.702 | 4 | 22 | |

| AGE | 48 | 66.75 | 38.225 | 4 | 187 | |

| Size | 48 | 19.04 | 3.598 | 14 | 24 | |

| LEV | 48 | 86.95 | 16.162 | 0 | 93 | |

| ROA | 48 | 1.2939 | 0.725 | 0 | 3.59 | |

| FOWN | 48 | 0.56 | 0.501 | 0 | 1 | |

| Panel B: Spearman and (Pearson) correlation coefficient for the model variables (below) above the diagonal | ||||||

| HCD | SIZE | AGE | LEV | FOWN | ROA | |

| HCD | 1 | 0.096 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.251 | -0.085 |

| SIZE | 0.026 | 1 | 0.320* | -0.376** | -0.327* | 0.018 |

| AGE | 0.140 | 0.069 | 1 | -0.111 | -0.103 | -0.157 |

| LEV | -0.174 | -0.166 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.196 | -0.465** |

| FOWN | 0.211 | -0.353* | -0.016 | 0.020 | 1 | 0.355** |

| ROA | -0.048 | -0.169 | -0.295* | -0.350* | 0.355* | 1 |

Note: *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The results show increasing in the mean of HC disclosures from 2015 to 2017. However, the mean of HC disclosure for all observations is relatively high 14.87 14.34 and the standard deviation is 4.702, indicating that there is a tendency dispersion in HC disclosure, as shown in Figure 1.

The mean of size is 19.04 and the standard deviation is 3.598, this displays relatively small dispersion in banks’ size.

The mean of age is 66.75 and the standard deviation is 38.225, this means that there is a high dispersion which indicates a differentiation among Lebanese commercial banks age which is ranges of minimum 4 to 187 years as maximum. The mean of leverage is 86.95 and the standard deviation is 16.162. In addition, the mean of profitability measured by ROA is 1.2939 and the standard deviation is 0.72464. Concerning the foreign ownership determinant, the mean is 0.56 and the standard deviation is 0.501.

Panel B of Table 2 reveals the results of correlation coefficients matrix of the variables. The matrix indicates that the association between the dependent variable and the independent variables are insignificant. In addition, indicating that multi-collinearity problem will not be a major issue in the regression analysis, the model includes variables with correlations inferior to 0.5.

Table 3 presents the results of the regression analysis. Results show that the coefficient of determination (represented by R2) is 0.144. This means that the variables explain only 14.4% of changes in the HC disclosures. The adjusted R-squared value is 0.042, which means that 4.2% of the variations in the level of HC disclosures can be described by variations in size, leverage, profitability, foreign ownership and age of the Lebanese commercial bank.

| TABLE 3 Statistical Regression |

|||||

| HC Disclosure=α +β 1 size+β2 leverage+β3 profitability+β4 foreign ownership+β5age+ε | |||||

| Variables | Coefficient | t-test | Sig. (p- value) | VIF** | |

| (Constant) | 19.699 | 2.851 | |||

| SIZE | 0.066 | 0.323 | 0.748 | 1.196 | |

| LEV | -0.078 | -1.698 | 0.097 | 1.229 | |

| ROA | -1.491 | -1.300 | 0.201 | 1.532 | |

| FOWN | 3.064 | 1.965 | 0.056 | 1.356 | |

| AGE | 0.014 | 0.746 | 0.460 | 1.115 | |

| R Square | 0.144 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.042 | ||||

| N | 48 | ||||

| F | 1.413 | ||||

| Durbin-Watson | 1.977*** | ||||

Note: *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); **VIF shows the absence of multi-collinearity; ***The value of Durbin- Watson is 1.977, which mean that there are no autocorrelation problems in the sample.

Table 3 shows that the coefficient of the bank’s size is B=0.066 and p-value=0.748, that is mean an insignificant positive relation between size and HC disclosure. Thus, the research results are in accordance with many studies results that find larger bank will disclose more information concerning HC in order to increase benefits and reduce the agency cost. Accordingly, hypothesis H1 is accepted.

Bank’s leverage has insignificant negative impact on the extent of HC disclosure level over the 2015-2017 fiscal years, the coefficient value and p-value are respectively (B=-0.078 and p-value=0.097). Thus, hypothesis H2 is rejected. These results indicate that companies with low level of leverage disclose more HC information to inform about the company financial structure in the financial market which is due maybe to the Lebanese culture.

Furthermore, a very insignificant negative relationship between bank’s profitability and the level of HC disclosure of the Lebanese commercial banks, the coefficient is (B=-1.491 and pvalue= 0.201). It means that more a Lebanese commercial bank is profitable less the level of HC information is disclosed, thus the results of this research is consistent with many studies as (Brammer and Pvelin, 2006; Hossain and Hammami, 2009; Anifowoseet al., 2017). Therefore, hypothesis H3 is rejected.

Moreover, the relation between foreign ownership and HC disclosure level is significantly positive (at 10% level), the coefficient value B=3.064 and p-value=0.056. Therefore, hypothesis H4 is accepted. More the Lebanese commercial bank has a foreign shareholders structure more the will of disclosing HC information is increased in order to decrease the high level of information asymmetry caused by the difference of language, culture and geographical departure.

Finally, firm’s age with a coefficient B=0.014 and p-value=0.460) that’s mean an insignificant positive relation between the age of the Lebanese commercial bank and HC disclosure. Accordingly, hypothesis H5 is accepted. Older Lebanese banks will disclose more HC information as they have more experience and past archive.

Conclusion

Finally, this study tries to indicate the possible HC disclosure determinants in the Lebanese commercial banks. The study employed a content analysis of 48 sampled of Lebanese commercial banks using the HC index developed by the researcher that contain the most common indicators from previous studies and the most suitable for the banking sector over the fiscal year of 2015 and 2017. The data were analyzed using a multiple regression analysis.

Based on prior studies related to corporate HC disclosures, the study developed five hypotheses. Generally, the results from the data analyses confirmed the existence of a relation between the determinants of HC disclosure and the level of HC disclosure. Lebanese commercial banks profitability and leverage are not as one of the major determinants of HC disclosures. In contrast, size, foreign ownership and age are considered as determinants of HC disclosure, but with insignificant relationship.

Moreover, this study provide contribution to literature of the accounting research by developing an appropriate HC index in order to measure the level of HC disclosures in the annual reports of Lebanese banks. Besides, scarce studies have concentrated on the determinants of HC disclosures; this study is the first study that explores the determinants of HC disclosures in the commercial banks of Lebanon.

This study is important, first for the accounting and financial reporting boards by using the findings from this study when developing the financial reporting standard concerning the disclosure of HC information. Secondly, this study helps the investors to take in consideration and use the determinants of HC disclosures explored in the current study to identify the potential of HC disclosures in banks.

This study was restrained on HC only because it is considered as the main element of IC although the concept of HC is not clearly understood and poorly disclosed by some of Lebanese commercial banks. In addition, one of the major limitations that some banks disclose the values in the annual reports in a currency different than Lebanese currency, that’s why these banks are eliminated from the study and the operation of converting currency is one of the challenges that the researcher face because of the fluctuation of the exchange price and that could affect the reliability of the financial information in the bank annual reports.

In many studies the significance and the importance of HC is recognized but only few of researchers make efforts to quantify or measure it, which open new future research path. Another possibility for research could be by testing other determinants that could affect the level of HC disclosure in Lebanon for other than banking sectors, or compared with the banking sector in other countries.

Appendices

| Appendix A The Items Of Hc Index Collected From Previous Studies After 2 Phases |

||

| Human capital indicators | ||

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

| Collected from previous studies. | Selected based on the most common in the literature review. | |

| 1 | Salaries and wages (Flamholtz,1999; Huang et al., 2012; Haniffa et al., 2013; Rezai and Mousavi, 2015). | Salaries and wages. |

| 2 | Know-how ( Edvinsson and Malone,1997; IFAC,1998;CIMA, 2005) | Know-how. |

| 3 | Employee knowledge (knowledge related to work ) (Skandia, 1994; Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Johnson, 1999; Dzinkowski, 2000 ; Brennan and Connell, 2000; OECD, 2001; Davis and Harrison, 2001; Flamholtz et al., 2002; Bontiz and Fitz- enz, 2002; CIMA, 2005; Swart, 2006; Tovistiga & Tulugurova, 2009; Rizvi, 2010; Baron, 2011; chang and Lee, 2012; Rawal and Mahini, 2014; Kamath, 2014 Todericiu and serban, 2015). | Employee knowledge. |

| 5 | Employee work-related competences, competencies (IFAC,1998; Dzinkowski,2000 ; Flamholtz et al., 2002; Tovistiga & Tulugurova, 2009; Haniffa et al.,2013; Kamath, 2014; Rawal and Mahini, 2014; Todericiu and serban, 2015). | Competence. |

| 6 | Training (Bozbura, 2004; Baum, 2000; Dzinkowski, 2000; Vuolle et al., 2009; Haniffa et al., 2013; Rezai and Mousavi, 2015). | Training. |

| 7 | Entrepreneurial skills, leadership (IFAC, 1998; Miller et al., 1999; Johnson, 1999; Dzinkowski, 2000; Bozbura, 2004; CIMA, 2005). | entrepreneurial skills. |

| 8 | professional experience, expertise (Miller et al.,1999; Flamholtz et al, 2002; Bozbura, 2004; Vuolle et al., 2009; chang and Lee, 2012; Haniffa et al., 2013; Rawal and Mahini, 2014) . | professional experience, expertise. |

| 9 | Education levels ( Sveiby, 1997; IFAC, 1998; Baum, 2000; Bontis, 2000; Guthrie and Petty, 2000; Dzinkowski, 2000; Bozbura, 2004; CIMA,2005; Vuolle et al., 2009; Haniffa et al., 2013). | education levels. |

| 10 | Employee creativity and innovation (Baum, 2000; Dzinkowski,2000 ; Bozbura, 2004; Vuolle et al., 2009; Haniffa et al., 2013; Rawal and Mahini, 2014). | Employee creativity and innovation. |

| 11 | Employee relationship ( Baum, 2000; Pasher and shachar, 2007). | Employee relationship |

| 12 | Employee profile (age, number, gender ) (Pasher and shachar, 2007). | Employee profile. |

| 13 | Information technology literacy of staff (Miller et al., 1999). | Information technology literacy of staff. |

| 14 | Conventions and Conferences payments (Rezai and Mousavi, 2015). | conventions and conferences payments. |

| 15 | Staff turnover rate (Dzinkowski, 2000;Papmehl, 2004; Rezai and Mousavi, 2015). | Staff turnover rate. |

| 16 | Professional qualification (Vocational qualification) (IFAC, 1998; Dzinkowski, 2000; CIMA, 2005; li et al., 2008). | Professional qualification(Vocational qualification). |

| 17 | Occupational assessments (IFAC, 1998). | Occupational assessments. |

| 18 | Employee Satisfaction (Miller et al.,1999; Dzinkowski, 2000 ; Bozbura, 2004; Rizvi, 2010). | Employee Satisfaction. |

| 19 | Reactive abilities, changeability ( Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; IFAC, 1998; Bozbura, 2004). | Reactive abilities, changeability. |

| 20 | Innovative, proactive (Edvinsson and Malone,1997; CIMA,2005) | Innovative, proactive. |

| 21 | Employee attitudes principles (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Rudolf, 2004) | Employee attitudes principles. |

| 22 | behavior (moral values) Human Value (Guthrie and Petty, 2000; Dzinkowski, 2000; Cuganesan et al., 2007; Rizvi , 2010). | behavior (moral values- human values). |

| 23 | Motivation (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Miller et al.,1999; Dzinkowski, 2000; Meritum Guidelines, 2002; Ismail, 2005; li et al., 2008). | Motivation. |

| 24 | Employee commitments ( Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Bontis, 2000; Bontis and Fitz-enz, 2012). | Commitments. |

| 25 | Employee abilities, capabilities (Skandia, 1994; Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Dzinkowski, 2000; Davis and Harrison, 2001; Rizvi, 2010). | Employee abilities, capabilities. |

| 26 | Psychometric assessments(Guthrie and Petty, 2000; Marr and Moustaghfir, 2005) | |

| 27 | Dues and subscriptions ( Ekundayo and Odhigu, 2016). | |

| 28 | Development spend on the employee( Ekundayo and Odhigu, 2016). | |

| 29 | problem solving and communication skills (Payne, 2000; Rudolf, 2004). | |

| 30 | self-confidence (cooper et al.,1994; Urban, 2012). | |

| 31 | Individual and Collective Experiences Productivity (li et al.,2008). | |

| 32 | Employee flexibility (Meritum Guidelines, 2002; Ismail, 2005; li et al., 2008). | |

| 33 | Employee involvement with community (li et al., 2008) | |

| 34 | Other employee features (Huang et al., 2012) | |

| 35 | Human Resources (Lee et al., 2012). | |

| 36 | Ideas capital (Johnson,1999). | |

| 37 | Loyalty (Baharum and Pitt, 2009). | |

| 38 | Information gathering skills (Rudolf, 2004). | |

| 39 | learning capacity (Meritum Guidelines, 2002; Ismail, 2005). | |

| 40 | adaptation and packaging (Roos et al.,1998). | |

| 41 | Social competence (Sveiby, 1997; Cavell et al., 2003). | |

Source: developed by the researcher.

| Appendix B Total Scoring Of Hc Indicators For The Annual Reports Of 2015 And 2016 |

|||||||

| Banks name | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||

| Human capital | % | Human Capital | % | Human capital | % | ||

| 1. | Bank Audi S.A.L | 17 | 68 | 22 | 88 | 21 | 84 |

| 2. | B.L.C. Bank S.A.L. | 12 | 48 | 13 | 52 | 10 | 40 |

| 3. | Blom Bank S.A.L. | 16 | 64 | 19 | 76 | 19 | 76 |

| 4. | Byblos Bank S.A.L. | 18 | 72 | 17 | 68 | 20 | 80 |

| 5. | Fransabank S.A.L | 5 | 20 | 21 | 84 | 21 | 84 |

| 6. | IBL Bank SAL | 9 | 36 | 15 | 60 | 17 | 68 |

| 7. | Bankmed S.A.L. | 14 | 56 | 10 | 40 | 15 | 60 |

| 8. | Societe Generale De Banque Au Liban S.A.L. (SGBL) | 13 | 52 | 10 | 40 | 10 | 40 |

| 9. | Jammal Trust Bank S.A.L. | 14 | 56 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 64 |

| 10. | Libano-Francaise S.A.L. | 20 | 80 | 11 | 44 | 11 | 44 |

| 11. | Audi Private Bank S.A.L | 4 | 16 | 7 | 28 | 12 | 48 |

| 12. | Banque Bemo S.A.L. | 16 | 64 | 18 | 72 | 19 | 76 |

| 13. | Banque Misr Liban S.A.L. (BML ) | 4 | 16 | 18 | 72 | 16 | 64 |

| 14. | Credit Libanais S.A.L | 21 | 84 | 18 | 72 | 18 | 72 |

| 15. | Lebanon And Gulf Bank S.A.L | 18 | 72 | 19 | 76 | 16 | 64 |

| 16. | Cedrus Bank S.A.L | 18 | 72 | 14 | 56 | 14 | 56 |

| Total | 219 | 240 | 255 | ||||

Source: developed by the researcher.

References

- Abeysekera, I., (2003). Intellectual accounting scorecard: Measuring and reporting intellectual capital. Journal of American Academy of Business, 3(1), 422-427.

- Abeysekera, I., (2011). The relation of intellectual capital disclosure strategies and market value in two political settings. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 12(2), 319-338.

- Abeysekera, I., & Guthrie, J., (2005). An empirical investigation of annual reporting trends of intellectual capital in Sri Lanka. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(3), 151-63.

- Abhayawansa, S., & Abeysekera, I. (2008). Forthcoming 'An explanation of human capital disclosure from the resource based perspective. Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, 12(1), 51-64.

- Al-Akra, M., Eddie, I.A., & Ali, M.J. (2010). The influence of the introduction of accounting disclosure regulation on mandatory disclosure compliance: Evidence from Jordan. The British Accounting Review, 42(3), 170-186.

- Alam, I., & Deb, S.K. (2010). Human resource accounting disclosure (HRAD) in Bangladesh: Multifactor regression analysis: A decisive tool of quality assessment. The Cost and Management, 9-13.

- Al-Hamadeen, R., & Suwaidan, M. (2014). Content and determinants of intellectual capital disclosure: Evidence from annual reports of the Jordanian industrial public listed companies. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(8).

- Anifowose-M, Ab., Rashid, H.M., & Bin-Annuar, H.A. (2017). Determinant of human capital disclosure in the post IFRS regime: An examination of listed firms in Nigeria. Malaysian Accounting Review (MAR), 16(2), 1-30.

- Banque de liban. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.bdl.gov.lb/

- Baharum, M.R., & Pitt, M. (2009). Determining a conceptual framework for green FM intellectual capital. Journal of Facilities Management, 7(4), 267-282.

- Barako, D.G., Hancock, P., & Izan, H.Y., (2006). Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by kenyan companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14(2), 107-125.

- Baron, A. (2011). Measuring human capital. Strategic HR Review, 10(2), 30-35.

- Bontis, F.E. (2002). Intellectual capital ROI: A casual map of human capital antecedents and consequents. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 3(3), 223-247.

- Bontis, N. (2003). Intellectual capital disclosure in Canadian corporations. Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, 7(1), 9-20.

- Bozzolan, S., Favotto, F., & Ricceri, F., (2003). Italian annual intellectual capital disclosure: An empirical analysis. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4(4), 543-58.

- Branco, M.C., Delgado, C., Sa, M., & Sousa, C. (2010). An analysis of intellectual capital disclosure by Portuguese companies. EuroMed Journal of Business, 5(3), 258.

- Brennan, N., & Connell, B., (2000). Intellectual capital: Current issues and policy implications. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(3), 206-240.

- Brennan, N., (2001). Reporting intellectual capital in annual reports: evidence from Ireland. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 14(4), 423-36.

- Brooking, A. (1996). Intellectual capital: Core asset for the third millennium enterprise. International Thomson Business Press, New York.

- Brüggen A., Vergauwen P., & Dao M. (2009). Determinants of intellectual capital disclosure: Evidence from Australia. Management Decision, 47(2), 233-245.

- Bukh, P.N., Nielsen, C., Gormsen, P., & Mouritsen, J. (2005). Disclosure of information on intellectual capital in Danish IPO prospectuses. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18(6).

- Cavell, T.A., Meehan, B.T., & Fiala, S.E. (2003). Assessing social competence in children and adolescents. In C. R. Reynolds & R.W. Kamphaus (Eds.), Handbook of psychological and educational assessment of children (pp.433- 454). New York: Guilford Press.

- Chadwick, C., & Dabu, A. (2009). Human resources, human resource management, and the competitive advantage of firms: Toward a more comprehensive model of causal linkages. Organization Science, 20(1), 253-272.

- Chang, C., & Lee, Y. (2012). Verification of the influences of intellectual capital upon organizational performance of taiwan-listed info-electronics companies with capital structure as the moderator. The Journal of International Management Studies, 7, 80-92.

- Chow, C.W., & Wong-Boren, A., (1987). Voluntary financial disclosure by Mexican corporations. The Accounting Review, 62(3), 533-541.

- Cooper, A.C., Gimeno-Gascon, F.J., & Woo, C.Y., (1994). Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(5), 371-395.

- Cordazzo, M., & Vergauwen P., (2012). Intellectual capital disclosure in the UK biotechnology IPO prospectuses. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 16, 4-19.

- Cormier, D., Aerts, W., Ledoux, M. J., & Magnan, M. (2009). Attributes of social and human capital disclosure and information asymmetry between managers and investors. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 26(1), 71-88.

- Cuganesan, S., Finch, N., & Carlin, T., (2007). Intellectual capital reporting: A human capital focus. Proceedings of the Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies, 12(1), 21-25.

- Dammak, S., Triki, M., & Boujelbene, Y. (2008). A study on intellectual capital disclosure determinants in the European context. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 5, 417-430.

- Dominguez, A.A. (2012). Company characteristics and human resource disclosure in Spain. Social Responsibility Journal, 8(1), 4-20.

- D?enopoljac, V., Janoševic, S., & Bontis, N. (2016). Intellectual capital and financial performance in the Serbian ICT industry. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 17(2), 373-396.

- Dzinkowski, R, (2000). The measurement and management of intellectual capital: An introduction. Management Accounting, 78(2), 32-6.

- Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M.S. (1997). Intellectual capital: The proven way toestablish your company's real value by measuring its hiddenbrainpower. London: Judy Piatkus.

- Ekundayo, O., & Odhigu, F, (2016). Determinants of human capital accounting in Nigeria. Journal of Accounting, 1.

- El-Gazzar, S.M., Fornaro, J.M., & Jacob, R.A. (2008). An examination of the determinants and contents of corporate voluntary disclosure of management’s responsibilities for financial reporting. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 23(1), 95-114.

- Fernando, D.R.M., & Ariovaldo, D.S. (2010). Determinants of corporate voluntary disclosure in Brazil. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract¼1531767

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics, (Third Edition). London: Sage.

- Fontana, F.B, Macagnan C.B. (2013). Factors explaining the level of voluntary human capital disclosure in the Brazilian capital market. Omnia Science, Intangible Capital, 9(1), 305-321.

- Forte W., Tucker J., Matonti G., & Nicolò G. (2017). Measuring the intellectual capital of Italian listed companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(4), 710-732.

- Gheisari T., & Amozesh, N. (2016). An analysis of the effect of intellectual capital disclosure on liquidity stock of companies listed in Tehran stock exchange. Journal of Administrative Management, Education and Training, 12(3), 71-78.

- Guthrie, J., & Petty R. (2000). Intellectual capital literature review. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(2), 155-176.

- Guthrie, J., & Petty, R. (2000). Intellectual capital: Australian annual reporting practices. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(3), 241-251.

- Haji A.A., & Ghazali M. (2012). Intellectual capital disclosure trends: some Malaysian evidence. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 13(3), 377-397.

- Haniffa, R.M., & Cooke, T.E. (2002). Corporate governance structure and performance of Malaysian listed companies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(1), 391-430.

- Harris, L. (2000). A theory of intellectual capital. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 2(22), 22-37.

- Harrison, S., & Sullivan, P.H. (2000). Profiting from intellectual capital learning from leading companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(1), 33-46.

- Hossain, M., & Hammami, H. (2009). Voluntary disclosures in the annual reports of an emerging country: The case of Qatar. Advances in Accounting, Incorporating Advances in International Accounting, 25, 255-65

- Huang, C.C., Luther, R.G., Tayles, M.E. & Lin, B. (2012). Intellectual capital information gaps. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 9(4), 448-463.

- Huang, C.C., Luther R., Tayles M., & Haniffa R. (2013). Human capital disclosures in developing countries: figureheads and value creators. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 14(2), 180-196.

- Ismail, M. (2005). The influence of intellectual capital on the performance of telekom Malaysia. Unpublished Dissertation, University Technology Malaysia, Johor Baru.

- Jensen, M.C., & Meckling, W.H. (1976).Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305-360.

- Jindal, S., & Kumar, M. (2012). The determinants of HC disclosures of Indian firms. Journal ofIntellectual Capital, 13(2), 221-247.

- Johnson, W.H.A. (1999). An integrative taxonomy of intellectual capital: Measuring the stock and flow of intellectual capital components in the firm. International Journal of Technology Management, 18, 562-575.

- Joshi, M., & Ubha, S.D. (2009). Intellectual capital disclosures: The search for a new paradigm in financial reporting by the knowledge sector of Indian economy. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(5), 575-582.

- Kamardin, H., Abu Bakar, R., & Ishak, R. (2017). Intellectual capital disclosure: The effect of family and non-executive directors on board. Advance Science Letters, 23(4), 3102-3106.

- Kamath, B. (2008). Intellectual capital disclosure in India: Content analysis of ‘TecK’ firms. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 12(3), 213-24.

- Kang, H., & Gray, J. (2011). Reporting intangible assets: Voluntary disclosure practices of top emerging market companies. The International Journal of Accounting, 46(4), 402-423.

- Kateb, I. (2015). Voluntary human capital disclosure in French annual reports. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 12(4), 323-341.

- Khlifi, F., & Bouri, A. (2010). Corporate disclosure and firm characteristics: A puzzling relationship. Journal of Accounting- Business & Management, 17(1), 62-89.

- Khumalo, B. (2012). Defining economics in the twenty first century. Modern Economy, 3, 597-607.

- Leitner, K.H. (2004). Intellectual capital reporting for universities: Conceptual background and application for Austrian universities. Research Evaluation, 13(2), 129-140.

- Lee, G., Kim, T., Kim, W.G., Park, S.S.S., & Jee, B. (2012). Intellectual capital and business performance: What structural relationships do they have in upper-upscale hotels? International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(4), 391-408.

- Lev B., Cañibano L., & Marr B. (2005). An accounting perspective on intellectual capital. Perspectives on Intellectual Capital, Oxford.

- Leventis, S., & Weetman, P. (2004). Voluntary disclosures in an emerging capital market: Some evidence from the Athens stock exchange. Advances in International Accounting, 17, 227-250.

- Li, J., Pike, R., & Haniffa, R. (2008). Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK firms. Accounting and Business Research, 38(2), 137-159.

- Mangena M., Pike R., & Li J. (2010). Intellectual capital disclosure practices and effects on the cost of equity capital: UK evidence. The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, CA House.

- Marr, B., & Moustaghfir, K. (2005). Defining intellectual capital: A three-dimensional approach. Management Decision, 43(9), 1114.

- Marston, C., & Shrives, P. (1991). The use of disclosure indices in accounting research: A review article. British Accounting Review, 23(3), 195-210.

- Meek, G.K., Roberts, C.B., & Gray, A.J. (1995). Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by US, UK and continental European multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 555-572.

- Melegy M. (2013). Determinants of the accounting disclosure on intellectual capital and its impact on the financial performance empirical study on the listed Egyptian companies. Thesis.

- Meressa H. (2016). Determinants of intellectual capital performance: Empirical evidence from Ethiopian banks. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 7(13).

- Meritum-Guideline. (2002). Guidelines for managing and reporting on intangibles.Intellectual Capital Report: European Union, Fundación Airtel Móvil, Madrid.

- Mohammad, A.J. (2015). Human capital disclosures: Evidence from Kurdistan. European Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance Research, 3(3), 21-31.

- Möller, K., Gamerschlag, R., & Guenther, F. (2011). Determinants and effects of human capital reporting and controlling. Journal of Management Control, 22(3), 311-333.

- Mondal, A., & Ghosh, K. (2014). Determinants of intellectual capital disclosure practices of Indian companies. Journal of Commerce & Accounting Research, 3(3).

- Mouritsen, J., Bukh, P.N., & Marr, B. (2004). Reporting on intellectual capital: Why, what and how? Measuring Business Excellence, 8(1), 46-54.

- Muttakin, M., Khan, A., & Belal, A. (2015). Intellectual capital disclosures and corporate governance: An empirical examination. Advances in Accounting, Incorporating Advances in International Accounting, 31, 219-227.

- Nagar, V., Nanda, D., & Wysocki, P. (2003). Discretionary disclosure and stock-based incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34(1-3), 283-309.

- Nielsen, C., Rimmel, G., Bukh, P.N., Koga, C., Tadanori, Y., & Sakakibara, S. (2005). Intellectual capital in Japanese and Danish IPO prospectuses: A comparative analysis. Working Paper, Department of Accounting, Finance and Logistics, Aarhus School of Business, Aarhus.

- OECD. (2001). The well-being of nations: The role of human capital and social capital. Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

- Oliveira, L., Rodrigues, L.L. & Craig, R. (2013). Stakeholder theory and the voluntary disclosure of intellectual capital information. International Journal of Governance, 3(1), 1-20.

- Ordoñez de Pablos, P., (2005). Intellectual capital reports in India: Lessons from a case study. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(1), 141-149.

- Ousama Abdulrahman A., Abdul-Hamid F., & Abdul Rashid H.M. (2012). Determinants of intellectual capital reporting: Evidence from annual reports of Malaysian listed companies. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 2(2), 119-139.

- Ousama, A., & Fatima, A. (2010). Factors influencing voluntary disclosure: Empirical evidence from Shariah approved companies. Malaysian Accounting Review, 9(1), 85-103.

- Ousama, A., Fatima, A.H., & Hafiz?Majdi, A. R. (2012). Determinants of intellectual capital reporting: Evidence from annual reports of Malaysian listed companies. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 2(2), 119-139.

- Payne, J. (2000). The unbearable lightness of skill: The changing meaning of skill in UK policy discourses and some implications for education and training. Journal of Education Policy, 15(3), 353- 369 .

- Pena, I. (2002). Intellectual capital and business start-up success. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 3(2), 180-198.

- Perera, A., & Thrikawala, S. (2012). Impact of human capital investment on firm financial performances an empirical study of companies in Sri Lanka. IPEDR, 54(3).

- Pettersson, J., & Rylme, H. (2003). Voluntary disclosure of human capital: An explorative study of voluntary disclosure practices in Swedish annual reports. Master Thesis, Go¨teborg University.

- Rawal, N., & Mahini S.A. (2014). Models and methods of intellectual capital accounting. Advances in Economics and Business Management (AEBM), 1(1).

- Rizvi, Y. (2010). Human capital development role of human resource during mergers and acquisitions. African Journal of Business Management, 5, 261-268.

- Roos J., Roos G., Dragonetti N.C., & Edvinsson L. (1998). Intellectual capital: Navigating in the new business landscape. New York University Press, New York.

- Roslender R., & Fincham R. (2001). Thinking critically about intellectual capital accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(4), 383-399.

- Rudolf, W. (2004). Human capital as the centre of all business in building human capital: A South African perspective, I. Boninell & T.W.A. Meyer (eds.). Johannesburg: Knowres Publishing.

- Shamsudin L., & Yian R. (2013). Exploring the relationship between intellectual capital and performance of commercial banks in Malaysia. Rent Seeking Contest and Indirect Risk Preference, 2(2).

- Stewart, T.A. (1997). Intellectual capital: The new wealth of organizations. Currency Doubleday, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Stewart, T.A. (2000). Intellectual capital: the wealth of organizations. London: Nicholas

- Stropnik, N., Korošec, B., & Tominc, P. (2017). The relationship between the intellectual capital disclosure and cost of debt capital: A case of slovenian private audited organizations. Naše gospodarstvo/Our Economy, 63(4), 3-16.

- Sveiby, K.E. (1997). The “invisible” balance sheet”. Retrieved from http;//www.sveiby.com/articles/Invisible Balance.html

- Gheisari, T., & Amozesh, N.(2016). An analysis of the effect of intellectual capital disclosure on liquidity stock of companies listed in Tehran stock exchange. Journal of Administrative Management, Education and Training, 12(3), 71-78.

- Tovistiga, G., & Tulugurova, E. (2009). Intellectual capital practices: A four region comparative study. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 10(1), 70-80.

- Urban, B., (2012). A metacognitive approach to explaining entrepreneurial intentions. Management Dynamics, 21(2), 16-33.

- Uyar, A., & K?l?ç, M. (2013). Discovering the nature and extent of human capital disclosure, and investigating the drivers of reporting: evidence from an emerging market. International Journal of Accounting and Finance, 4(1), 63-85

- Uyar, A., & Kilic, M. (2012). The influence of firm characteristics on disclosure of financial ratios in annual reports of Turkish firms listed in the Istanbul Stock Exchange. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 8(2), 137-156.

- Wallace, R.S.O., & Naser, K. (1995). Firm-specific determinants of the comprehensiveness of mandatory disclosure in the corporate annual report of firms listed on the stock exchange of Hong Kong. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 14, 311-368.

- Wang, K., Sewon, O., & Claiborne, M.C. (2008). Determinants and consequences of voluntary disclosure in an emerging market: evidence from China. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 17, 14-30.

- White G., Lee A., Yuningsih Y., Nielsen Ch., & Bukh Per, N. (2010). The nature and extent of voluntary intellectual capital disclosures by Australian and UK biotechnology companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 11(4), 519-536.

- Whiting, R.H., & Woodcock, J. (2011). Firm characteristics and intellectual capital disclosure by Australian companies. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 15(2), 102-126.

- Williams, S.M. (2001). Is a company’s intellectual capital performance and intellectual capital disclosure practices related: Evidence from public listed companies from the FTSE 100? Paper presented at the Fourth World Congress on IC, Hamilton.

- Yi, A., & Davey, H. (2010). Intellectual capital disclosure in Chinese (mainland) companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 11(3), 326-347.