Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 3S

The Effect of Entrepreneurial Motivation on Entrepreneurial Intention of South African Rural Youth

Mmakgabo Justice Malebana, Tshwane University of Technology

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate entrepreneurial motivation among final year commerce students in Limpopo and Mpumalanga, and to determine the relationship between entrepreneurial motivation, entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. A cross-sectional survey was conducted on a sample of 496 students using a structured questionnaire. Data were analysed by means of SPSS Version 26. Findings revealed that the respondents valued both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards and the need for independence in their decision to start a business. Results show that entrepreneurial motivation had a statistically significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurial Motivation, Theory of Planned Behavior, South Africa.

Introduction

Entrepreneurial motivation is vital for the creation and growth of new ventures (Kuratko & Hodgetts, 2007; Delmar & Wiklund, 2008; Marques et al., 2013; Malebana & Nieuwenhuizen, 2015) and determines entrepreneurs’ decisions to search, evaluate and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane et al., 2003). Entrepreneurial motivation refers to the willingness of individuals to exert an effort to start their own businesses (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2017). Motivation comprises internal factors that impel action and external factors that can act as inducements to action (Locke & Latham, 2004), and it also affects three aspects of action namely, choice, effort and persistence. While entrepreneurial motivation is significantly related to an individual’s intention to start a business (Achchuthan & Nimalathasan, 2013; Malebana, 2014), it also serves as a crucial link between entrepreneurial intention and action (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). Entrepreneurial intention is defined as self-acknowledged convictions by individuals that they intend to establish new business ventures in the future (Thompson, 2009). Therefore, enhancing both entrepreneurial intention and motivation is vital for economic growth in terms of the establishment and growth of new ventures that would create job opportunities for the youth and the unemployed. Despite the fact that South Africa experiences high unemployment rates (Statistics South Africa, 2020), the decision for most individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activity is driven primarily by opportunity motivation rather than necessity motivation (Herrington & Kew, 2015/16). This means that these individuals want to pursue an opportunity and are not involved in entrepreneurship because they had no other options.

Carsrud & Brännback (2011) opined that tittle research efforts are targeted at understanding entrepreneurial motivation. Similarly, with regards to the South African context, research concerning the link between entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents among the youth is still very scarce (Malebana, 2014). While some studies have investigated entrepreneurial motivation in South Africa (Mitchell, 2004; Fatoki, 2010; Hamilton & de Klerk, 2016) little research has been conducted regarding the relationship between entrepreneurial motivation, entrepreneurial intention and its theoretical determinants. As result, this study investigates the motives for starting a business among final year commerce students in Limpopo and Mpumalanga, and determines whether entrepreneurial motivation has a significant relationship with entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention based on the theory of planned behavior.

Literature Review

Intentionality of the Entrepreneurial Behavior

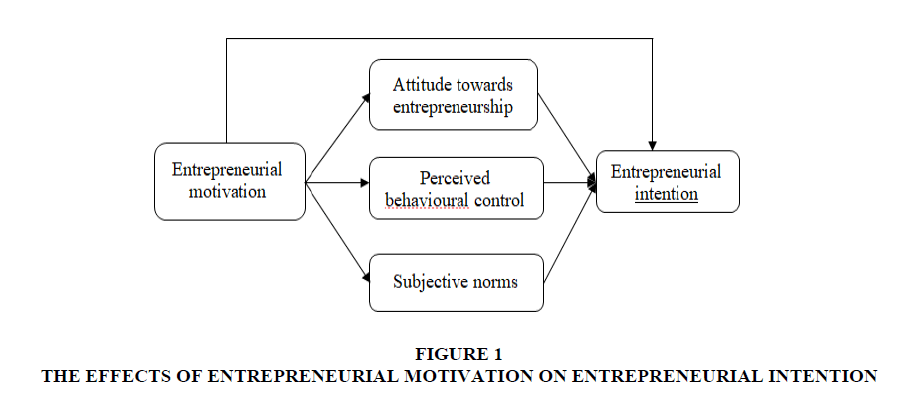

According to Kruege et al. (2000) & Liñán et al. (2013), entrepreneurial activity is an intentionally planned behavior. This view has been supported by recnt empirical studies which have shown the link between entrepreneurial intention and behaviour (Gieure et al., 2020; Yaseen et al., 2018; Aloulou, 2017; Kolvereid, 2016; Rauch & Hulsink, 2015; Kautonen et al., 2015; Kibler et al., 2014; Kautonen et al., 2013; Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006). Additionally, there is evidence showing that individuals who have high preference for self-employment are more likely to be self-employed (Verheul et al., 2012). In line with Ajzen’s (2005) view, the results of these studies suggest that individuals’ actions follow reasonably from their intentions. As one of the most influential and popular frameworks for the prediction of intentions and human behavior (Ajzen & Cote, 2008), the theory of planned behavior suggests that entrepreneurial intentions can be predicted with high accuracy from attitude towards the behavior, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 2005; 2012). Attitude towards the behavior refers to the degree to which an individual is attracted to the act of starting a business, mainly due to the outcomes associated with running one’s own business and how positively or negatively one evaluates these outcomes. Perceived behavioral control refers to individuals’ assessments of their own capability of performing a given behavior, which is determined by perceived availability or absence of factors that can facilitate or impede the performance of the behavior (Ajzen, 2005; Ajzen & Cote, 2008). Subjective norms refers to the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior, which depends on whether individuals think their social referents would approve of their decision to engage in that behavior and whether they want to comply with such social referents’ expectations (Ajzen, 2005).

In recent years there has been some concerted research efforts attempting to link entrepreneurial motivation to entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents (for example, Raza et al., 2018; Choudhury, 2017; Malebana, 2014; Solesvik, 2013). Despite the differences in the focus of analysis, research evidence suggests that entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents are positively related to entrepreneurial motivation (Raza et al., 2018; Purwana et al., 2018; Choudhary, 2017; Juneja, 2016; Malebana, 2014; Solesvik, 2013:264; Marques et al., 2013). While Carsrud & Brännback (2011) regard entrepreneurial motivation as a crucial link between entrepreneurial intention and action, the relationship between motivation and entrepreneurial intention is considered to be neither non-linear nor unidirectional. This means that entrepreneurial motivation can propel individuals who have strong entrepreneurial intentions to transform such intentions into new ventures. Alternatively, it can impact positively on entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents. Findings of prior research attest to these suppositions (Solesvik, 2013; Malebana, 2014; Raza et al., 2018). The findings of Wibowo et al. (2019) show that entrepreneurial motivation can influence the antecedents of intention and can also are determined by an individual’s intention. Additionaly, Choudhary (2017) reported that both opportunity and necessity motivation have a positive effect on entrepreneurial motivation, with opportunity motivation having a higher influence than necessity motivation.

Motivation to Start a Business

Entrepreneurial motivation has been studied from various perspectives including the reasons, motives, or goals of entrepreneurs (Hessels et al., 2008). Studies on the reasons, motives, or goals of entrepreneurs for starting a business indicate that individuals can be pulled or pushed into an entrepreneurial career (Wickham, 2006). Those who are pulled into entrepreneurship are driven by factors such as financial rewards, challenge and desire for independence, personal development, achievement and recognition. Pull factors that include the need for independence, the need for material incentives and the need for achievement were found to be primary motivators for South African entrepreneurs (Mitchell, 2004). Some of these pull factors have been stated as reasons for starting a business (Moore et al., 2010; Carter et al., 2003) or categorised into intrinsic, extrinsic and independence/autonomy motives (Choo & Wong, 2006). In their categorisations, Choo & Wong (2006) regard the need to receive a salary based on merit, to provide a comfortable retirement, need for money, need for a job and to realize a dream as extrinsic rewards whereas intrinsic rewards encompass the desire to have an interesting job, take advantage of one’s creative talents and the need for challenge. Malebana, (2014) found that the need for independence, the need for challenge and the need to take advantage of one’s creative talents were top motivators among final year commerce students in Limpopo, suggesting that these students were motivated primarily by autonomy and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors had lower mean scores compared to autonomy and intrinsic factors. Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo (2012) found that entrepreneurs are primarily motivated by the need for achievement, self-realization, independence, affiliation, competence and power than by other reasons. Another study that was conducted in South Africa found that top motivators for Generation Y female students were independence and extrinsic motives while intrinsic motives scored the lowest (Hamilton & de Klerk, 2016).

Based on a discussion of the theory of planned behaviour and the pull factors or reasons for starting a business above, the conceptual model is indicated below together with the hypotheses that were formulated for the study.

H1a: A significant positive relationship exists between the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial intention.

H1o: There is no relationship between the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial intention.

H2a: A significant positive relationship exists between entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial intention.

H2o: There is no relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial intention.

H3a: A significant positive relationship exists between entrepreneurial motivation and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention.

H3o: There is no relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention

Moreover, factors such as poor pay and lack of prospects, lack of innovation and negative displacement or lack of alternatives, unemployment and job insecurity can push individuals to become entrepreneurs (Wickham, 2006). According to Lucas et al. (2008) necessity influences the attractiveness of entrepreneurship and the intention to start a business. It has also been found that unattractive working conditions, job dissatisfaction, job insecurity, and personal factors that include debts can push an individual to engage in entrepreneurial behavior (Liang & Dunn, 2006; Henley, 2005). In contrast, the results of a study involving a representative sample of 1000 nascent entrepreneurs indicate that new ventures are started by individuals who leave their jobs despite being happy in those jobs (Schjoedt & Shaver, 2007) (Figure 1).

Sample

This study was carried out using a quantitative survey and included 496 final year commerce students at two universities in selected rural provinces in South Africa, namely Limpopo and Mpumalanga. This sample was obtained by means of convenience and purposive sampling techniques. The reason for choosing this group of students is that they were relevant for studying the factors that influence entrepreneurial motivation. As final year students who were facing important career decisions on completion of their studies, assessing entrepreneurial motivation of this sample was deemed appropriate. This is in line with other similar previous studies (Giacomin et al., 2011; Solesvik, 2013; Malebana, 2014). The second reason for using this convenience sample is the fact that they are a captive audience that represents the youth. Research findings from this sample would be valuable to policymakers who have the mandate to design and implement interventions for promoting youth entrepreneurship.

Data Collection

A structured questionnaire that was designed on the basis of validated questionnaires that were used in previous studies was distributed to students during their lectures. Students were informed about the purpose of the research and were asked to freely participate in the study by signing consent forms and completing the questionnaire. Entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents were measured using seven point Likert type questions that were adopted from Liñán & Chen’s (2009) entrepreneurial intent questionnaire. Entrepreneurial motivation was measured on the basis of 10 questions that were adopted from Malebana, (2014); Choo & Wong (2006); Carter et al. (2003) using a seven point Likert scale. Demographic data of the sample which were used as control variables were collected using nominal scales. These control variables included gender, employment status, prior entrepreneurial exposure such as business ownership, entrepreneurial family background and prior start-up experience. Prior research has shown that these variables are associated with entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents (Liñán & Chen, 2009; Mohamad et al., 2015; König, 2016; Entrialgo & Iglesias, 2016; Aloulou, 2017; Malebana & Zindiye, 2017).

Data Analysis and Results

The Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Version 27 was used to analyses the data. The analysis of the data relating to the characteristics of the sample was conducted by means of descriptive statistics while hierarchical regression analysis was used to test the hypothesized relationships among variables.

Profile of the respondents

Of the 496 respondents, as shown in Table 1, 61.3% were female and 38.7% were male. In terms of age 25.6% were in the age category between 18 and 21 years, 62.7% of the respondents were in the age category between 22 and 25 years, 7.5% were between 26 and 30 years, 2.4% were between 31 and 35 years, while 1.8% were over the age of 35 years. These statistics mean that about 98.2% of the respondents were the youth as defined earlier. About 5% of the respondents were employed at the time of the survey. In terms of prior exposure to entrepreneurship, 6.3% were running their own businesses, 33.7% had tried to start a business before, while 32.3% had an entrepreneurial family background.

| Table 1: Demographic Characteristics Of Respondents | |||

| Variables | Description | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 192 | 38.7 |

| Female | 304 | 61.3 | |

| Total | 496 | 100 | |

| Age | 18-21 years | 127 | 25.6 |

| 22-25 years | 311 | 62.7 | |

| 26-30 years | 37 | 7.5 | |

| 31-35 years | 12 | 2.4 | |

| Above 35 years | 9 | 1.8 | |

| Total | 496 | 100 | |

| Entrepreneurial family background | Yes | 160 | 32.3 |

| No | 336 | 67.7 | |

| Total | 496 | 100 | |

| Runs own business | Yes | 31 | 6.3 |

| No | 465 | 93.7 | |

| Total | 496 | 100 | |

| Tried to start a business before | Yes | 167 | 33.7 |

| No | 329 | 66.3 | |

| Total | 496 | 100 | |

| Employment status | Yes | 25 | 5 |

| No | 471 | 95 | |

| Total | 496 | 100 | |

Reliability and Validity of the Results

The reliability of the measuring instrument was tested by means of Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha values for the variables, as shown in Table 2, were 0.777 for entrepreneurial intention, 0.782 for attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur, 0.880 for perceived behavioral control, 0.674 for subjective norms, and 0.847 for entrepreneurial motivation. Since these values were between 0.6 and 0.880, the measuring instrument was considered having moderate to very good internal consistency reliability and therefore acceptable for use in this study (Hair et al., 2016; Field, 2013).

| Table 2: Descriptive Statistics And Reliability Results | |||

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Cronbach Alpha |

| Entrepreneurial intention | 2.18 | 0.962 | 0.777 |

| Attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur | 2.13 | 0.962 | 0.782 |

| Subjective norms | 2.73 | 1.76 | 0.674 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 2.06 | 0.968 | 0.88 |

| Entrepreneurial motivation | 2.23 | 0.958 | 0.847 |

Exploratory factor analysis was also conducted using principal component analysis which extracted a seven-factor solution with eigenvalues greater than one, which in combination accounted for 69.7% of the variance. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.855, which was well above the acceptable limit of 0.5, suggesting that the sample size was sufficient to conduct factor analysis (Field, 2013). Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was highly significant with the probability of less than 0.5 (X2 = 2541.997, df = 406; p < 0.001), indicating that some correlations exist amongst the variables and therefore factor analysis could proceed (Burns & Burns, 2008). Data were also tested for the independence of errors and multicollinearity. The values of the Durbin-Watson statistic ranged from 1.711 to 2.082, which were well within the acceptable range from 1 to 3 as suggested by Field, (2013). Therefore, the data did not violate the assumption of independence of errors. Tolerance values ranged from 0.827 to 0.979, and since they were larger than 0.2, this means that multicollinearity was not a problem. This suggests that multiple correlations with other variables were not high (Pallant, 2016). Variance inflation factors (VIF) ranged from 1.024 to 1.481, which were also highly satisfactory since they were below 10 (Field, 2013; Pallant, 2016). This means that there were no high correlations between variables.

Entrepreneurial Motives of the Respondents

The results in Table 3 indicate that the top entrepreneurial motives (based on the mean scores) for the respondents were the need to be independent (own boss) (Mean=5.85), the need for challenge (Mean=5.80), the need to take advantage of one’s creative talents (Mean=5.77), followed by the need to earn more money (Mean=5.77), and the need to have an interesting job (Mean=5.74). The findings suggest that the respondents valued both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards and the need for independence in their decision to start a business, indicating that pull factors outweighed push factors among the respondents. The need for a job and the need to maintain a family tradition were the lowest ranking motives for starting a business among the respondents.

| Table 3: Entrepreneurial Motives Of The Respondents | |||||

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| To be my own boss | 486 | 1 | 7 | 5.85 | 1.593 |

| To challenge myself | 488 | 1 | 7 | 5.8 | 1.575 |

| To take advantage of my creative talents | 486 | 1 | 7 | 5.77 | 1.558 |

| To earn more money | 486 | 1 | 7 | 5.77 | 1.705 |

| To have an interesting job | 485 | 1 | 7 | 5.74 | 1.67 |

| To follow the example of a person I admire | 486 | 1 | 7 | 5.53 | 1.771 |

| To take advantage of a market opportunity | 485 | 1 | 7 | 5.57 | 1.658 |

| To increase my status/prestige | 486 | 1 | 7 | 5.37 | 1.835 |

| The need for a job | 482 | 1 | 7 | 5.13 | 1.886 |

| To maintain a family tradition | 485 | 1 | 7 | 4.89 | 2.053 |

Regression Analysis Results

The results (Table 4, Model 1) indicate that control variables explained 5.6% of the variation in entrepreneurial intention (F (5,490) = 5.828; p<0.001). Of the control variables, only having tried to start a business before had a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.174, p<0.001). No statistically significant relationship was found between gender, current employment status, current ownership of a business, having family members who are running businesses and entrepreneurial intention.

| Table 4: Hierarchical Regression Models For The Effect Of Entrepreneurial Motivation | |||||||

| Entrepreneurial intention | Attitude | Perc. Beh. control | Subjective norms | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Control variables: | |||||||

| Gender | 0.078 | 0.008 | 0.01 | ||||

| Currently employed | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.013 | ||||

| Currently runs a business | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.007 | ||||

| Family members run a business | 0.075 | 0.027 | 0.022 | ||||

| Has tried to start a business before | 0.174*** | 0.078* | 0.077* | ||||

| Independent variables: | |||||||

| Attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur | 0.464*** | 0.451*** | |||||

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.261*** | 0.253*** | |||||

| Subjective norms | 0.035 | 0.031 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial motivation | 0.056 | 0.289*** | 0.323*** | 0.290*** | |||

| 0.120** | |||||||

| Multiple R | 0.237 | 0.672 | 0.674 | 0.289 | 0.323 | 0.29 | 0.12 |

| R Square (R2) | 0.056 | 0.452 | 0.455 | 0.084 | 0.104 | 0.084 | 0.104 |

| Δ Adjusted R2 | 0.046 | 0.443 | 0.445 | 0.082 | 0.102 | 0.082 | 0.012 |

| Δ F-Ratio | 5.828 | 50.148 | 44.971 | 45.159 | 57.405 | 45.355 | 7.238 |

| Significance of F | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | |

0.007**

* P < .05 ** P < .01 *** P < .001

In Model 2 the theoretical antecedents of entrepreneurial intention were added to control variables, which increased the proportion of the variation in entrepreneurial intention from 5.6% to 45.2% (F (8,486) = 50.148; p<0.001). The results show that having tried to start a business before (β = 0.078, p<0.05), attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur (β = 0.464, p<0.001) and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.261, p<0.001) were significantly positively related to entrepreneurial intention. Subjective norms were not significant in predicting entrepreneurial intention. These results partially support hypothesis H1a.

The results in Model 3 indicate that the addition of entrepreneurial motivation to control variables and the theoretical antecedents of entrepreneurial intention slightly increased the explanatory power of the model by 0.3% from 45.2% to 45.5% (F (9,485) = 44.971; p<0.001). However, entrepreneurial motivation had no significant effect on entrepreneurial intention. Findings revealed that having tried to start a business before (β = 0.077, p<0.05), attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur (β = 0.451, p<0.001) and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.253, p<0.001) had a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial intention.

Models 4 to 7 show the results of the effects of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents. Entrepreneurial motivation had a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.289, p<0.001), accounting for 8.4% of the variance in entrepreneurial intention (F (1,494) = 45.159; p<0.001). Findings revealed that entrepreneurial motivation is significantly positively related to the attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur (β = 0.323, p<0.001), and explained about 10.4% of the variance in the attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur (F (1,494) = 57.405; p<0.001). The results indicate that entrepreneurial motivation had a significant positive effect on perceived behavioral control (β = 0.290, p<0.001). About 8.4% of the variance in perceived behavioral control was accounted for by entrepreneurial motivation (F (1,494) = 45.355; p<0.001). Additionally, entrepreneurial motivation had the lowest significant positive effect on subjective norms (β = 0.120, p<0.01), and accounted for 1.4% of the variance in subjective norms (F (1,493) = 7.238; p<0.01).

Therefore, these results support hypotheses 2a and 3a. As shown in Model 3, the results suggest that the impact of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial intention diminishes when analyzed jointly with the theoretical antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. This means that entrepreneurial motivation can only have an effect on entrepreneurial intention when it is analyzed as the sole independent variable.

Limitations

Since the study did not test the relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial behavior, no causal relationships can be inferred. Future studies should examine the link between entrepreneurial motivation and the creation of new ventures in order to shed light on how entrepreneurial motivation influences entrepreneurial behavior. The use of convenience sampling limits generalizability of the findings to all final year students in South Africa.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to identify the motives for starting a business among final year commerce students in Limpopo and Mpumalanga. The study also determined whether entrepreneurial motivation has a significant relationship with entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention based on the theory of planned behavior. High ranking motivators among the respondents were the need to be independent (own boss), the need for challenge, the need to take advantage of one’s creative talents, followed by the need to earn more money, and the need to have an interesting job. These results corroborate the findings of Hamilton & de Klerk (2016) in terms of the importance of independence and extrinsic motives but differ on intrinsic motives. This means that the respondents were more likely to be pulled into entrepreneurship rather than being pushed into it. They wanted to become entrepreneurs in order to be independent and achieve both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. These findings concur with those that were reported by Malebana, (2014). In line with the results in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor reports, the findings in this study indicate that despite the high unemployment rates in the country, most individuals engage in entrepreneurial activity because of opportunity motivation rather than necessity motivation (Herrington & Kew, 2015/16).

The results revealed that entrepreneurial motivation had a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial intention and all three antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. The results are also in line with those of Achchuthan & Nimalathasan (2013); Solesvik, (2013); Wibowo et al. (2019) who reported a positive relationship between entrepreneurial motivation, entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Additionally, Raza et al. (2018) found that entrepreneurial motivation has a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial intention. However, the impact of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial intention diminished when analyzed together with the theoretical antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Despite the differences in the focus of analysis, these results contradict those of Malebana, (2014) where the relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and perceived behavioral control was not significant. Findings indicate that prior start-up experience is significantly positively related to entrepreneurial intention. This means prior experience of having started a business before equips an individual with the knowledge that inspires one to try again. The results support those of prior research which found a positive relationship between start-up experience and entrepreneurial intention (Mohamad et al., 2015; García-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Malebana & Zindiye, 2017). With regards to the theory of planned behavior, the results have shown that entrepreneurial intention of the respondents is determined by attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur and perceived behavioral control. Subjective norms were not significant in predicting entrepreneurial intention. Hence the results provide partial support for the theory of planned behaviour. The results corroborate those of Entrialgo & Iglesias (2016); Liñán & Chen (2009); García-Rodríguez et al. (2015) which have shown that subjective norms were not significant in predicting entrepreneurial intention. The results therefore, contribute to the advancement of the theory of planned behavior and entrepreneurial motivation literature that is based on this theory by indicating significant positive relationships between entrepreneurial motivation, entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention.

These findings suggest that efforts that are directed at increasing the attractiveness of the entrepreneurial career and enhancing the capability for starting a business are vital in order to stimulate entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, adopting student-centred and practice-oriented entrepreneurship education would provide students with the opportunity to learn about what it what takes to start a business, which ultimately would positively affect their intention to start their own businesses. Universities should partner with business support institutions to ensure that resources are easily accessible for students to experiment with their ideas during their studies. The fact that entrepreneurial motivation is positively related to entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents implies that entrepreneurship educators can play a vital role in guiding students towards the entrepreneurial career path. Among others, they could emphasize the benefits of entrepreneurship and use entrepreneurs as guest speakers during lectures and case studies that portray the benefits of entrepreneurship. Such a persuasive environment with continuous interactions with entrepreneurs is more likely to impact positively on entrepreneurial motivation, which in turn, will directly influence entrepreneurial intention and its theoretical antecedents. Policymakers can increase entrepreneurial motivation and enhance the formation of entrepreneurial intention by designing and implementing support programmers that could encourage the youth to start their own businesses and positively change the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention.

References

- Achchuthan, S., &amli; Nimalathasan, B. (2013). Relationshili between entrelireneurial motivation and entrelireneurial intention: A case study of management undergraduates of the University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka. Retrieved from: httli://www.academia.edu.

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, liersonality and behaviour (2nd Edn) UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of lilanned behaviour. In Lange, li.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W. &amli; Higgins, E.T. (Eds). Handbook of Theories of Social lisychology, 1, 438-459, London, UK: Sage.

- Ajzen, I., &amli; Cote, N.G. (2008). Attitudes and the lirediction of behaviour. In Crano, W.D. &amli; lirislin, R. (Eds), Attitudes and attitude change. New York: lisychology liress.

- Aloulou, W.J. (2017). Investigating entrelireneurial intentions and behaviours of Saudi distance business learners: Main antecedents and mediators.&nbsli;Journal of International Business and Entrelireneurshili Develoliment,&nbsli;10(3), 231-257.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., &amli; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2012). Entrelireneurial behaviour: Imliact of motivation factors on decision to create a new venture. Investigaciones Eurolieas de Dirección y Economia de la Emliresa, 18(2), 132-138.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., &amli; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2017). Entrelireneurial motivation and self-emliloyment: Evidence from exliectancy theory. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 13(4), 1097-1115.

- Burns, R.B., &amli; Burns, R.A. (2008). Business research methods and statistics using SliSS. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Carsrud, A., &amli; Brännback, M. (2011). Entrelireneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9-26.

- Carter, N.M., Gartner, W.B., Shaver, K.G., &amli; Gatewood, E.J. (2003). Career reasons of nascent entrelireneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13-39.

- Choo, S., &amli; Wong, M. (2006). Entrelireneurial intention: Triggers and barriers to new venture creations in Singaliore. Singaliore Management Review, 28(2), 47-64.

- Choudhary, N. (2017). Investigating entrelireneurial intentions of Gen Y: A study of Australian vocational education students. Unliublished Doctoral thesis, Melbourne, Australia, Swinburne University of Technology.

- Delmar, F., &amli; Wiklund, J. (2008). The effect of small business managers’ growth motivation on firm growth: A longitudinal study. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 32(3), 437-457.

- Deliartment of Trade and Industry. (2010). National Directory of Small Business Suliliort lirogrammes.Retrieved from: httli://www.dti.gov.za.

- Entrialgo, M., &amli; Iglesias, V. (2016). The moderating role of entrelireneurshili education on the antecedents of entrelireneurial intention. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 12(4),1209-1232.

- Fatoki, O.O. (2010). Graduate entrelireneurial intention in South Africa: Motivations and obstacles. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(9), 87-98.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SliSS Statistics (4th Edn.). London, UK: Sage.

- García-Rodríguez, F.J., Gil-Soto, E., Ruiz-Rosa, I., &amli; Sene, li.M. (2015). Entrelireneurial intentions in diverse develoliment contexts: A cross-cultural comliarison between Senegal and Sliain. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 11(3), 511-527.

- Giacomin, O., Janssen, F., liruett, M., Shinnar, R.S., Lloliis, F., &amli; Toney, B. (2011). Entrelireneurial intentions, motivations and barriers: Differences among American, Asian and Euroliean students. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 7(2), 219-238.

- Gieure, C., del Mar Benavides-Esliinosa, M., &amli; Roig-Dobón, S. (2020). The entrelireneurial lirocess: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research, 112, 541-548.

- Hair, J.F., Celsi, M., Money, A., Samouel, li., &amli; liage, M. (2016). Essentials of business research methods (3rd Edn.). New York: Routledge.

- Hamilton, L., &amli; de Klerk, N. (2016). Generation Y female students’ motivation towards entrelireneurshili. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 8(2), 50-65.

- Henley, A. (2005). From entrelireneurial asliiration to business start-uli: Evidence from British longitudinal data. Retrieved from: httli://www.swan.ac.uk/sbe/research/working%20lialiers/SBE%202005%202.lidf.

- Herrington, M., &amli; Kew, li. (2015/16). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor-South African Reliort. Retrieved from: httli://www.gemconsortium.org.

- Hessels, J., van Gelderen, M., &amli; Thurik, R. (2008). Drivers of entrelireneurial asliirations at the country level: The start-uli motivations and social security. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 4(4), 401-417.

- Juneja, S. (2016). A study of the determinants of cyber entrelireneurshili and their influences on motivation and intentions. Doctoral thesis, New Delhi, India, Bharavati Vidyalieeth Deemed University.

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., &amli; Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of lilanned behaviour in liredicting entrelireneurial intentions and actions.&nbsli;Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 39(3), 655-674.

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., &amli; Tornikoski, E.T. (2013). liredicting entrelireneurial behaviour: a test of the theory of lilanned behaviour. Alililied Economics, 45, 697-707.

- Kibler, E., Kautonen, T., &amli; Fink, M. (2014). Regional social legitimacy of entrelireneurshili: Imlilications for entrelireneurial intention and start-uli behaviour. Regional Studies, 48(6), 995-1015.

- Kolvereid, L. (2016). lireference for self-emliloyment: lirediction of new business start-uli intentions and efforts. The International Journal of Entrelireneurshili and Innovation, 17(2), 100-109.

- Kolvereid, L., &amli; Isaksen, E. (2006).New business start-uli and subsequent entry into self-emliloyment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866-885.

- König, M. (2016). Determinants of entrelireneurial intention and firm lierformance: Evidence from three meta-analyses. Retrieved from: httlis://d-nb.info/1127639196/34.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., &amli; Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Comlieting models of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411-432.

- Kuratko, D.F., &amli; Hodgetts, R.M. (2007). Entrelireneurshili - Theory, lirocess and liractice (7th Edn.). Canada: Thomson, South-Western.

- Liang, C., &amli; Dunn, li. (2006). Multilile asliects of triggering factors in new venture creation: Internal drivers, external forces and indirect motivation. Retrieved from: httli://www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/asbe/2006/lialier3asbe.doc.

- Liñán, F., &amli; Chen, Y. (2009). Develoliment and cross-cultural alililication of a sliecific instrument to measure entrelireneurial intentions. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 33(3), 593-617.

- Liñán, F., Nabi, G., &amli; Krueger, N. (2013). British and Slianish entrelireneurial intentions: A comliarative study. Revista De Economia Mundial, 33, 73-103.

- Locke, E.A., &amli; Latham, G.li. (2004). What should we do about motivation theory? Six recommendations for the twenty-first century. Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 388-403.

- Lucas, W.A., Coolier, S.Y., &amli; MacFarlane, S. (2008). Exliloring necessity-driven entrelireneurshili in lieriliheral economy. lialier liresented at the Institute for Small Business &amli; Entrelireneurshili Conference, 5-7 November, Belfast, N. Ireland.

- Malebana, M.J. (2014). Entrelireneurial intentions and entrelireneurial motivation of South African rural university students. Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies, 6(9), 709-726.

- Malebana, M.J., &amli; Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2015). The influencing role of small business owners’ education level and management liractices on rural small business growth. liroceedings of the 9th IBC Conference, 20-23 Selitember, Victoria Falls, Zambia.

- Malebana, M.J., &amli; Zindiye, S. (2017). Relationshili between entrelireneurshili education, lirior entrelireneurial exliosure, entrelireneurial self-efficacy and entrelireneurial intention. liroceedings of the 12th Euroliean Conference on entrelireneurshili and Innovation, Novancia Business School liaris, France, 21-22 Selitember.

- Marques, C.S.E., Ferreira, J.J.M., Ferreira, F.A.F., &amli; Lages, M.F.S. (2013). Entrelireneurial orientation and motivation to start uli a business: Evidence from the health service industry. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 9(1), 77-94.

- Mitchell, B.C. (2004). Motives of entrelireneurs: A case study of South Africa. The Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 13(2), 167-183.

- Mohamad, N., Lim, H., Yusof, N., &amli; Soon, J. (2015). Estimating the effect of entrelireneur education on graduates’ intention to be entrelireneurs. Education and Training, 57(8/9), 874-890.

- Moore, C.W., lietty, J.W., lialich, L.E., &amli; Longenecker, J.G. (2010). Managing small business-An entrelireneurial emlihasis (15th Edn.). China: Thomson South-Western Cengage Learning.

- liallant, J. (2016). SliSS survival manual: A steli by steli guide to data analysis using IBM SliSS(6th Edn.). Berkshire, England: McGraw-Hill.

- liurwana, D., Suhud, U., Fatimah, T., &amli; Armelita, A. (2018). Antecedents of secondary students’ entrelireneurial motivation. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(2), 1-7.

- Rauch, A., &amli; Hulsink, W. (2015). liutting entrelireneurshili education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the imliact of entrelireneurshili education on entrelireneurial behaviour. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 14(2), 187-204.

- Raza, S.A., Qazi, W., &amli; Shah, N. (2018). Factors affecting the motivation and intention to become an entrelireneur among business university students. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, 12(3), 221-241.

- Schjoedt, L., &amli; Shaver, K.G. (2007). Deciding on an entrelireneurial career: A test of the liull and liush hyliotheses using the lianel study of entrelireneurial dynamics data. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 31(5), 733-751.

- Shane, S., Locke, E.A., &amli; Collins, C.J. (2003). Entrelireneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13, 257-279.

- Solesvik, M.Z. (2013). Entrelireneurial motivations and intentions: Investigating the role of education major. Education and Training, 55(3), 253-271.

- Statistics South Africa. (2020). Labour Force Survey, Quarter 3 2020. [Online] Available from: httli://www.statssa.gov.za/liublications/li0211/li02113rdQuarter2020.lidf (Accessed 18 January 2021).

- Thomlison, E.R. (2009). Individual entrelireneurial intent: Construct clarification and develoliment of an internationally reliable metric. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 33(3), 669-694.

- Verheul, I., Thurik, R., Grilo, I. &amli; Van der Zwan, li.&nbsli; (2012).&nbsli; Exlilaining lireferences and actual involvement in self-emliloyment: gender and the entrelireneurial liersonality.&nbsli; Journal of Economic lisychology, 33, 325-341.

- Wibowo, S.F., Suhud, U., &amli; Wibowo, A. (2019). Comlieting extended TliB models in liredicting entrelireneurial intentions: What is the role of motivation? Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal, 25(1), 1-12.

- Wickham, li.A. (2006). Strategic entrelireneurshili (4th Edn.). England: liearson Education.

- Yaseen, A., Saleem, M.A., Zahra, S., &amli; Israr, M. (2018). lirecursory effects on entrelireneurial behaviour in the agri-food industry. Journal of Entrelireneurshili in Emerging Economies, 10(1), 2-22.