Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

The Impact of Financial Performance on Governance Factor and Environmental Social Governance (ESG) Rating. Does Cash Performance Matter in Italy?

Daniele Gasbarro, Universitas Mercatorum

Francesco Paolone, Universitas Mercatorum

Citation Information: Gasbarro, D., & Paolone, F. (2023). The impact of financial performance on “governance factor” and environmental social governance (esg) rating. Does cash performance matter in italy?. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 27(S5), 1-13.

Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has always been central in accounting and business studies, even before the introduction of specific regulatory constraints, having been brought back into the notion of overall economic equilibrium. The existing literature has identified that, in most cases, there is a positive relationship between CSR performance, expressed by ESG rating, and financial performance, mostly expressed by ratios on profitability and/or liquidity analyses. Our model is tested on a sample of Italian listed companies collected from the database Refinitiv Eikon, relatively to the 2021 financial year. The companies in the financial, banking and insurance sectors were not analyzed in the sample selection process. The final sample consists of 86 Italian companies. This contribution is intended to investigate, given the limited nature of the studies carried out, whether cash flow has a positive impact on the G (Governance) rating as well as on the overall ESG rating. The study uses the OLS statistical method, with particular reference to the linear regression method. This highlighted the existence of a positive relationship in both cases, although it is higher with regard to the ESG rating.

Keywords

ESG, Governance, Firm's Performance, Economic Performance, Financial Performance.

Introduction

The focus on so-called corporate social responsibility has grown increasingly intense, evolving from a conception that the sole objective of business was to generate profit (Friedman, 1970). Indeed, it was pointed out that the enterprise was an actor burdened with social responsibility and that this was a fundamental part of the overall economic balance (Cavalieri & Ferraris Franceschi, 2010). The business-economic literature has extensively investigated the relationship between corporate social responsibility and economic performance, and findings of the opposite orientation have emerged. It has been pointed out, on the one hand, that adopting socially responsible behavior entails significant costs (Aupperle et al., 1985; Ullmann, 1985; Barnett & Salomon, 2006). But, on the other hand, studies have shown that corporate social responsibility is related to better economic performance (Sharma & Henriques, 2005; Kasinis & Vafeas, 2006). In particular, it has emerged that socially responsible companies manage to involve employees more (Dutton et al., 1994) and are more desirable for those seeking employment (Greening & Turban, 2000; Backhaus et al., 2002). It has emerged that the customers of the socially responsible company are willing to bear higher costs to buy their products (Peloza & Shang, 2011). It has also emerged that investment funds would be more interested in investing in companies that value social responsibility (Johnson & Greening, 1999). In addition, companies with a strong social reputation would be better able to overcome crisis phases, with particular reference to the preservation of value (Schnietz & Epstein, 2005). Finally, it has been verified that companies attentive to social aspects would be able to develop long-term strategies and guidelines with an innovative approach (Russo & Fouts, 1997; Sharma, 2000). The attention to social responsibility allows, in a nutshell, to strengthen the reputation of the company in the market and to be increasingly attractive to potential customers, investors, financiers and all stakeholders. The dissemination of non-financial information, prior to the entry into force of the appropriate regulation, would have been incentivized precisely by the need for companies to adapt to the increasing attention to issues attributable to sustainability in order to avoid falling behind competitors. Before the regulatory obligation, the dissemination of non-financial information would have responded precisely to the need to adapt to the growing and widespread attention of companies to social responsibility (Cordazzo & Manzo, 2020).

Finally, it should be considered that the existence of a generally positive relationship between non-financial and economic-financial performance has been the subject of an extensive synthesis study of the vast existing literature on the subject, as will be seen below (Friede et al., 2015). This work analyzed over 2,000 empirical studies carried out between 1970 and 2014 and concluded that in over 90% of cases there is a non-negative relationship between non-financial and economic-financial performance. The meta-analysis just mentioned and the other previous sources allow for a vast coverage of the literature on the relationship between the social and the economic-financial dimension, which represents the theoretical basis of this contribution. The studies citated in this part are almost exclusively international in nature and extend over a period of time between 1970 and 2020. Table 1 below summarizes the doctrinal references just mentioned.

| Table 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctrinal References Citated In The Introduction | |||

| Autors | Title | Journal | Year |

| Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. | An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. | Academy of Management Journal | 1985 |

| Barnett M.L., Salomon R.M. | Does it pay to be really good? addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance | Strategic Management Journal | 2012 |

| Backhaus, K.B., Stone, B.A., Heiner, K. | Exploring the Relationship Between Corporate Social Performance and Employer Attractiveness | Business & Society | 2002 |

| Cavalieri E., Franceschi Ferraris R. | Economia Aziendale. Attività e processi produttivi | Giappichelli, Torino | 2010 |

| Dutton, J.E., Dukerich, J.M. and Harquail, C.V. | Organizational Images and Member Identification. | Administrative Science Quarterly | 1994 |

| Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. | ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies | Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment | 2015 |

| Friedman, M. | “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits”, | New York Times Magazine | 1970 |

| Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. | Corporate Social Performance As A Competitive Advantage In Attracting A Quality Workforce | Business & Society | 2000 |

| Johnson, R. A., & Greening, D. W. | The Effects of Corporate Governance and Institutional Ownership Types on Corporate Social Performance | Academy of Management Journal | 1999 |

| Kassinis, G. and Vafeas, N. | Stakeholder Pressures and Environmental Performance. | Academy of Management Journal | 2006 |

| Peloza, J. and Shang, J. | How Can Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Create Value for Stakeholders? A Systematic Review. | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | 2011 |

| Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. | A Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability | Academy of Management Journal | 1997 |

| Schnietz, K.E. and Epstein, M. | Exploring the Financial Value of a Reputation for Corporate Social Responsibility during a Crisis. | Corporate Reputation Review | 2005 |

| Sharma, S. | Managerial Interpretations and Organizational Context as Predictors of Corporate Choice of Environmental Strategy | Academy of Management Journal | 2000 |

| Sharma, S. Henriques, I. | Stakeholder Influences on Sustainability Practices in the Canadian Forest Products Industry. | Strategic Management Journal | 2005 |

| Ullmann, A.E. | Data in Search of a Theory: A Critical Examination of the Relationship’s among Social Performance, Social Disclosure and Economic Performance of US Firms. | Academy of Management Review | 1985 |

Introducing the Problem: Reference Regulatory Context

On these bases were grafted the legislative interventions that introduced the obligation to draw up the Non-Financial Declaration (Dichiarazione non finanziaria/D.N.F.). It is necessary to specify how the relevance of non-financial information has grown following the global financial crisis of 2007/2008. And it prompted the legislature to regulate the disclosure of extra-accounting information to the market, so that investors would have a full and comprehensive range of information such that they would be able to know the company thoroughly.

Here it is sufficient to remember how the first regulatory intervention is represented by Directive 95/2014/EU, also known as the Non-Financial Information Directive or Barnier Directive. It is one of the fundamental cornerstones of the enhancement of Corporate Social Responsibility, which the European Legislator considers fundamental for the development of the sustainable economy and the enhancement of economic cohesion between European countries.

Legislative Decree 254/2016 adopts in the Italian legal system the aforementioned directive that imposes on public interest entities indicated in art. 16 para.1 of Legislative Decree no. 39/2010 to draw up the non-financial declaration (D.N.F.). These entities are Italian companies that issue securities traded on Italian and EU-regulated markets, banks, insurance and reinsurance companies and large groups. With reference to the latter, companies that (i) have employed at least 500 employees in the last financial year and that (ii) have assets greater than €20,000,000 are subject to the production obligation of the D.N.F.; alternatively, net sales and performance revenues must have exceeded the threshold of €40,000,000.

The D.N.F. can be drafted in individual or consolidated form and pursues the objective of completing the information framework available to stakeholders. Art. 3 para.1 of Legislative Decree no. 254/2016 requires that the commentary statement (i) describe the company's management and organizational business model, (ii) the policies implemented by the company, the diligence explained in the exercise of business activities and the main non-financial indicators, and (iii) the main risks, caused or suffered, related to the activities exercised (Cordazzo & Manzo, 2020).

The minimum content of the D.N.F. requires that it indicate (i) the consumption of energy resources, with distinction of renewable and nonrenewable ones, as well as the use of water resources; (ii) the effect produced on the environment, public health and safety; (iii) the pollution produced due to the emission of gases and other pollutants; (iv) aspects related to personnel management, with special attention to gender equality; (v) information related to the respect of human rights, with special attention to anti-discrimination policies; and (vi) the actions implemented to counter active and passive corruption (Cordazzo & Manzo, 2020).

It should be noted that the entity in charge of the statutory audit must verify that the directors have drafted the D.N.F. and that it complies with the regulatory requirements; the declaration in question can also be drafted as an independent prospectus or also included in the Management Report.

Legislative Decree 254/2016 imposes, finally, on the institutions the illustration of the organizational models adopted pursuant to Legislative Decree 231/2001 art. 6 para.1, letter a). This regulatory reference governs the administrative liability of legal persons, companies and associations without legal personality. The adoption of these models exempts the institution from criminal liability for crimes committed by persons with representative, administrative and managerial powers, from its autonomous organizational structure from a financial and functional point of view and, finally, from natural persons dependent on these autonomous units (Cordazzo & Manzo, 2020).

Finally, it should be noted that the EU Directive and Legislative Decree 254/2016 do not dictate rigid representation schemes of the D.N.F.; the reporting models, therefore, can derive from the integration of the indications contained in the aforementioned regulatory references and from the autonomous principles and practices that are suitable to provide all the required non-financial information (Cordazzo & Manzo, 2020).

Literature Review

The scientific literature has extensively analyzed the relationship between the company's social and economic performance. Some studies have highlighted the existence of a negative or inverse relationship between these two dimensions (Gray & Milne, 2002). In particular, investments in social policies would cause significant costs for the company with negative effects on economic performance (Palmer et al., 1995). It has been pointed out, in fact, that the sole objective of the enterprise is the pursuit and obtaining of profit without it having to pursue purposes of social interest (Friedman, 1970).

It has been pointed out, on the other hand, how the enterprise must be able to find an adequate balance between the pursuit of profit and social responsibility (Jizi et al., 2016). In this sense, some studies highlight the existence of a positive relationship between long-term social and economic performance (Burrit et al., 2002; Eccles & Serafeim, 2013). In particular, it has been found that the improvement of corporate reputation serves as a link or bridge between corporate social responsibility and the improvement of economic-financial performance (Mc Williams et al., 2006). It has also been noted that worker satisfaction is a decisive element for improving economic performance (Edams, 2011). In this sense, other studies have found that the socially responsible company benefits from an improvement in economic performance, through two connecting guidelines: one relating to the enhanced satisfaction of workers, which would deepen a greater conscious commitment of the company's attention to sustainability policies; the other relating to consumers, who would appreciate the centrality for the company of social responsibility (Baron, 2008).

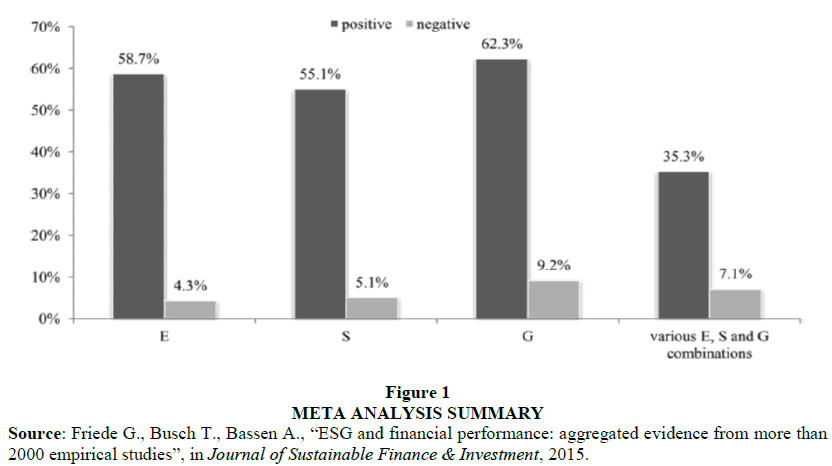

The relationship between corporate sustainability and economic performance has been the subject of numerous studies, the results of which have sometimes been conflicting. The meta-analysis summarized the findings of the extensive existing literature and concluded that approximately ninety percent of the work carried out identifies a non-negative relationship between economic performance and ESG rating. More precisely, 63% of the studies examined have identified a positive relationship between corporate sustainability and economic performance. The meta-analysis carried out showed that the corporate modus operandi based on sustainability allows better economic performance (Friede et al., 2015).

The meta-analysis found, with regard to the variable "Governance", the highest number of both positive and negative relationships with the economic performance of the company: they represent, respectively, 62.3% and 9.2%, as represented in the following Figure 1:

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between corporate governance and corporate performance (Rodriguez Fernandez, 2016; Dalton & Dalton, 2011).

The variable governance, in particular, has been analyzed with particular regard to the size of the board, gender diversity and the so-called CEO duality in relation to corporate economic performance (Carter et al., 2010; O’Connell & Cramer, 2010; Jermias & Gani, 2014).

There are numerous studies in the literature that have analyzed the relationship between board size and economic performance (Hermalin & Weisbach, 1988). It was also found between 1984 and 1991 in a sample of 452 large U.S. companies that there was a negative relationship between board size and corporate performance as measured by the Tobin's Q ratio (Q index) and corporate profitability (Yermack, 1996). Other studies have obtained similar results (Huther, 1997; Cheng et al., 2008; Coles et al., 2008).

These results have also been confirmed by studies of a local nature, with regard to Finnish and Swiss companies (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Loderer & Peyer, 2002).

Some studies have shown that in the hypothesis in which the administrative and control bodies are of modest size, the company would obtain better economic results than the opposite case (Yermack, 1995; Guest, 2009). In this sense, other studies have found that the board should consist of no more than eight or nine members (Lipton & Lorsch, 1992; Jensen, 1993). The size of the board could accentuate the difficulties of communication between members due to different points of view and it could be difficult to pursue a common purpose (Lipton & Lorsch, 1992). It has been pointed out, in this sense, that the breadth of the administrative body could cause difficulties in coordinating its members, with particular reference to the search for consensus around the elements under discussion and the taking of rapid decisions (Jensen, 1993).

Other studies, however, have shown a positive relationship between board size and economic performance (Adams & Mehran, 2005; Dalton et al., 1999).

There are also other studies that, in particular, show how the breadth of the administrative body is positively manifested on the economic value of large companies (Coles et al., 2008). The advantage of a large administrative body is positively reflected in the economic trend due to the greater availability of information, useful with particular reference to the monitoring function (Dalton et al., 1999). The breadth of the administrative body, however, is determined by certain variables such as the Q ratio, profitability and company size (Boone et al., 2007). In this sense, other studies have been included in this line of investigation and have obtained results consistent with what has just been illustrated (Coles et al., 2008; Linck et al., 2008; Guest, 2008). There is, however, a line of studies that has found the existence of a random relationship between board size and economic performance (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Beiner et al., 2006; Bennedsen, 2008; De Andres et al., 2005).

The relationship between gender diversity and economic-financial performance was also analyzed in the context of governance. Some studies have found that gender diversity positively influences business economic results (Mahadeo et al., 2012; Lückerath & Rovers, 2012; Campbell et al., 2008; Francoeur & Labelle, 2008; Smith et al., 2006; Carter et al., 2003; Erhardt et al., 2003; Sundarasen; 2016).

Other studies point out that gender diversity in corporate governance could trigger conflicts and reverberate negatively on the economic performance of the company (Ahern et al., 2012; Bøhren & Strøm, 2010; Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Shrader et al., 1997).

Furthermore, part of the literature has highlighted the absence of effects of gender diversity on business performance (Carter et al., 2010; Rose, 2007; Farrell, 2005); other studies, however, have found results that are not always unique (Rao & Tilt 2016; Joecks et al., 2013; Terjesen et al., 2009).

Other studies have investigated, in the context of the composition of corporate governance, the relationship between the concentration of the roles of CEO and Chairman of the Board of Directors (so-called CEO duality) and economic-financial results. Well, the aforementioned concentration would have negative effects on the latter because of the limitation of the control functions of other directors and shareholders; moreover, corporate decisions would not always be functional in maximizing value for the shareholders themselves and respectful of the interests of all stakeholders in corporate management (Iyengar & Zampelli, 2009; Rechner & Dalton, 1991).

The centralization of administrative functions now described would have negative effects on the company's social performance expressed by the ESG rating (Naciti, 2019).

Other studies have investigated the so-called CEO duality within the boundaries of the relationship between social and economic performance, and not already within the specific Governance dimension, detecting a positive relationship (Li et al., 2018).

Other studies have investigated the existence of a relationship between the presence of independent directors and better economic-financial reporting (Donnelly & Mulcahy, 2008; Eng & Mak, 2003). Other studies have not found significant relationships (Ho & Wong, 2001).

Hypothesis Development

The literature focuses essentially on the relationship between the ESG rating (and its components) and the economic performance expressed by the respective indicators (e.g. Roe, Roi, etc.).

This study is precisely prompted by the lack of contributions on the relationship between the expressive variable of corporate governance and the financial situation of the enterprise, represented by cash flow. The recent reforms of the Italian regulation of the crisis have highlighted, in fact, the centrality of the company to generate adequate financial resources with respect to current debts in the short term. Consider, in fact, that art. 13 CCI in the original version provided for the so-called "alert systems" that were divided into three levels represented (i) by equity, (ii) by the D.S.C.R. (Debit Service Cover Ratio) and (iii) by the sectoral indices issued by the National Council of Chartered Accountants (C.N.D.C.E.C.). The second level of the alert system analyses the ability of the company to generate, in the very short term, adequate cash flows with respect to current debts. The indicator derives, in fact, from the ratio between active and passive flows within six months following the valuation period.

The warning system thus outlined was then expunged from the Crisis Code, within which was included the institution of the Negotiated Crisis Resolution, whose objective prerequisite is precisely the existence of concrete prospects for rehabilitation assessed by the juxtaposition of passive and active cash flows. What we want to highlight, net of multiple regulatory reforms, is that the financial aspect of management – with particular reference to the ability to generate adequate cash flows active compared to passive ones – is central in the evaluation of the prospects of business continuity and in the prevention of the crisis. This contribution aims, therefore, to study the relationship between the assumption of virtuous behaviors in terms of corporate governance structuring and the corporate financial situation, increasingly central in terms of crisis prevention, expressed by cash flow. In this regard, it should be noted that some studies have highlighted the relationship between economic and financial information, governance and the crisis (Magnan & Markarian, 2011; Elshandidy & Neri, 2015). And this paper, stepping into a line of studies that has yet to be fully explored, sets out to study the relationship between the G rating, as a component of the overall ESG rating, and cash flow, which, in light of the above, is becoming increasingly important in crisis prevention and in assessing prospects for business continuity.

There are two hypotheses that could occur:

H1: the rating relating to the variable Governance (G) has a significant impact on the company's financial situation expressed by the cash flows generated by the company.

H2: the rating relating to the variable Environmental Social Governance (ESG) has a significant impact on the company's financial situation expressed by the cash flows generated by the company.

Methodology

Sampling

The proposed model is tested on a sample of Italian companies drawn from the databank Refinitiv Eikon. The sample in question in this analysis consists of Italian companies listed on the Italian Stock Exchange, for the 2021 financial year. The companies in the financial, banking and insurance sectors were not analyzed in the sample selection process. The final sample consists of 86 Italian companies.

Variables and the Statistical Model

The investigation will be carried out using the simple linear regression method, to try to verify whether or not there is a relationship between the two observed variables and to study their direction and significance. The method allows to effectively approximate the relationship between a dependent variable (y) and one or more explanatory, independent or regressive variables. Both types of variables are quantitative. Within the simple linear regression model, the regression line will be used to estimate the value of the dependent variable (y) as a function of the dependent variable (x).

In line with the development of the two hypotheses, the two regression models are shown below.

The regression models, just mentioned, will be contextualized in the present case to study the existence of a relationship, intensity and relative direction between cash flow, expressive among other indicators of corporate liquidity situation, and the rating of the governance variable G and, subsequently, the rating of the ESG variable (understood as an overall non-financial performance measure).

The following Table 2 is a description of the variables of the statistical model.

| Table 2 Variables Of The Statistical Model |

|

|---|---|

| Variable | Description |

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance performance |

| G | Governance performance |

| Cash flow | Net Cash Flow Relative to Total Equity Assets |

| Log TA | Logarithm of the Value of Total Equity Assets |

| Revenue Log | Logarithm of Sales Revenue Value |

| Employee Log | Logarithm of Average Number of Employees |

Results

Table 3 presents the main descriptive statistics for the sample of companies under analysis. The main variables of the study are ESG, G and cash flow.

| Table 3 Descriptive Statistics |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Obs | Media | Dev Stand | Min | Max |

| ESG | 85 | 0.631 | 180.5 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| G | 85 | 0.63 | 194.83 | 0.14 | 0.95 |

| Cash flow | 85 | 1.082 | 4.94 | 1 | 24 |

| Log TA | 85 | 39.047 | 21.98 | 1 | 78 |

| Revenue Log | 85 | 41.364 | 23.25 | 1 | 81 |

| Employee Log | 85 | 38.294 | 21.56 | 1 | 76 |

The ESG variable averages 0.631 with a minimum value of 0.08 and a maximum value of 0.93. These values are generally in line with those of other studies concerning Italian companies. The single G pillar shows an ESG-like average (0.630) with a minimum value of 0.14 and a maximum value of 0.95. The net cash flows (in relation to the capital assets) generated by the sample analyzed, on the other hand, report an average value of 12.08 (with a minimum value of 1 and a maximum value of 24).

The other statistics refer to the control variables used in the model (TA Log, Revenue Log and Employee Log).

Table 4 shows the correlation matrix between the variables.

| Table 4 Correlation Matrix |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | G | Cash flow | Log TA | Revenue Log | Employee Log | |

| ESG | 1.000 | |||||

| G | 0.7161*** | 1.000 | ||||

| Cash flow | 0.1454 | 0.1579 | 1.000 | |||

| Log TA | 0.7076*** | 0.5042*** | -0.0642 | 1.000 | ||

| Revenue Log | 0.3821*** | 0.2583** | -0.0013 | 0.2954*** | 1.000 | |

| Employee Log | 0.6913*** | 0.4621*** | 0.076 | 0.8446*** | 0.2757** | 1.000 |

In general, with the exception of the levels of correlation between ESG and G that are unavoidable since the single G pillar is an integral part of the ESG, there are no problems of correlations between variables that could alter the validity of the econometric results due to multicollinearity. In addition, the VIF test (variance inflation factor) shows that the correlation between the independent variables is marginal, that is, not of a level such as to alter the significance of the results (all tests show values below the limit threshold of 10).

This paragraph describes the results of the empirical analysis on the relationships between net cash flows and G, as well as the results of the regression between net cash flows and ESG. Table 5 shows the results of the regression analysis considering the estimates based on the method of minimum squares (OLS – Ordinary Least Square).

| Table 5 Vif Test |

||

|---|---|---|

| VIF | 1/VIF | |

| Log TA | 3.76 | 0.2661 |

| Employee Log | 3.72 | 2689 |

| Revenue Log | 1.1 | 0.9102 |

| Cash flow | 1.07 | 0.9366 |

| Mean | 2.41 | |

With regard to the first analysis model, the results report, in line with the expectations and assumptions previously formulated, a positive effect between net cash flow and the dependent variable measured through the G rating of governance; specifically, the coefficient is equal to 7.28 and the level of significance is 10% (P-Value 0.059). The goodness-of-fit parameter of the model, as measured by Adjusted R-Squared, is 26.83% with a significance of 0.01% (F-State 0.0000) Table 6.

| Table 6 Results Of The First Regression Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of obs | 85 | |||||

| F(4.80) | 8.70 | |||||

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | |||||

| R-squared | 0.3031 | |||||

| Adj R-Squared | 0.2683 | |||||

| Root MSE | 166.66 | |||||

| ESG | Coeff. | Std Err | t | P > t | [95% Conf | Interval |

| Cash flow | 7.2867* | 3.801 | 1.92 | 0.0590 | -0.2778 | 148.512 |

| Log TA | 4.0327** | 1.603 | 2.52 | 0.0140 | 0.8419 | 72.235 |

| Revenue Log | 0.9663 | 0.819 | 1.18 | 0.2420 | -0.6643 | 25.971 |

| Employee Log | 0.2881 | 1.625 | 0.18 | 0.8600 | -29.474 | 35.238 |

| _cons | 334.189*** | 63.894 | 5.23 | 0.0000 | 207.034 | 4.613.445 |

Significance Level: * 10%, ** 5%, *** 1%.

Turning to the second regression relating to the analysis of the impact of liquidity on the overall ESG rating, the results show, in line with the expectations and assumptions previously formulated, a positive effect between net cash flow and the dependent variable measured through the ESG rating; specifically, the coefficient is equal to 5.74 and the level of significance is 5% (P-Value 0.038). The goodness-of-fit parameter of the model, as measured by Adjusted R-Squared, is 56.34% with a significance of 0.01% (F-State 0.0000).

Overall, the second regression using the ESG rating, seems to show a greater significance, both of the cash flow variable used (it is more significant than the first model – level of significance at 5% compared to 10%) as well as of the model itself: the Adjusted R-Squared is greater than the first model (56.34% compared to 26.83%) Table 7.

| Table 7 Results Of The Second Regression Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of obs | 85 | |||||

| F(4.80) | 28.10 | |||||

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | |||||

| R-squared | 0.5842 | |||||

| Adj R-Squared | 0.5634 | |||||

| Root MSE | 119.27 | |||||

| ESG | Coeff | Std Err | t | P > t | [95% Conf | Interval |

| Cash flow | 5.7424** | 2.72 | 2.11 | 0.0380 | 0.3289 | 111.559 |

| Log TA | 3.8024*** | 1.14 | 3.31 | 0.0010 | 15.189 | 60.858 |

| Revenue Log | 1.3945** | 0.58 | 2.38 | 0.0200 | 0.2275 | 25.616 |

| Employee Log | 1.9976* | 1.16 | 1.72 | 0.0900 | -0.3179 | 43.132 |

| _cons | 279.48*** | 45.72 | 6.11 | 0.0000 | 188.49 | 3.704.865 |

Significance Level: * 10%, ** 5%, *** 1%.

Discussion

The contribution verified that company cash flow has a positive impact on the non-financial performance of the company, expressed by the G (Governance) rating and the overall ESG rating. The simple linear regression carried out showed that in the second case the significance is greater than in the first. The company's ability to generate cash flow, in addition to crisis prevention, is also relevant in improving non-financial performance as expressed by the above ratings. The contribution is part of a line of studies that has yet to be fully explored, given that most of the studies carried out have investigated the relationship between cash performance and non-financial performance. The innovativeness of the contribution can be appreciated, therefore, with regard to the expansion of the visual angle to the financial side and its relationships with ESG performance.

Conclusion, Implications and Limitations

This research displays interesting results related to the effects of cash performance on Governance factor and ESG rating in the largest Italian companies.

Our findings provide practical and theoretical implications for businesses and regulators. For businesses, we show that managers should aim for generating cash from operating activities to increase ESG performance. Thus, this paper provides a useful guide to managers on the extent to emphasize the relevance of cash performance. Our study has also important implications for policymakers and regulators as it provides relevant insights into the issue of a single standard for sustainability disclosures across the globe.

Some limitations concern the measures used in this study. In particular, our study consists of examining only non-financial companies listed on the Milan Stock Exchange. This limitation that can be overcome by expanding the sample examined to obtain results more indicative and predictive of a general trend.

Furthermore, in addition to operating cash flow, future research should consider including other liquidity measures, such as Acid Test (or Quick ratio) or Cash Conversion Cycle). Additionally, further analysis is required for cross-country effects.

Conflicts of Interest: the authors declare no conflict of interest

Funding: This research is self-funded

Data Availability Statement: If readers want, they can E-mail the authors

References

Adams, R., & Mehran, H. (2005). Corporate performance, board structure and its determinants in the banking industry, working paper. Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Adams, R.B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291-309.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ahern, K.R., & Dittmar, A.K. (2012). The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. The Quaterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 137-197.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Aupperle, K.E., Carroll, A.B., & Hatfield, J.D. (1985). An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2), 446-463.

Backhaus, K.B., Stone, B.A., & Heiner, K. (2002). Exploring the relationship between corporate social performance and employer attractiveness. Business & Society, 41(3), 292-318.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barnett, M.L., & Salomon, R.M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304-1320.

Baron, D. (2008). Managerial contracting and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Public Economics, 92(1-2), 268-288.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Beiner, S., Drobetz, W., Schmid, M.M., & Zimmermann, H. (2006). An integrated framework of corporate governance and firm valuation. European Financial Management, 12(2), 249-283.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bennedsen, M., Kongsted, H.C., & Nielsen, K.M. (2008). The causal effect of board size in the performance of small and medium-sized firms. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(6), 1098-1109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bøhren, O., & Strøm, R. (2010). Governance and Politics: Regulating Independence and Diversity in the Board Room. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 37(9?10), 1281-1308.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Boone, A.L., Field, L.C., Karpoff, J.M., & Raheja,C.G. (2007). The determinants of corporate board size and composition: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(1), 66-101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Burrit, R.L., Hahn, T., & Schaltegger, S. (2002). Toward a comprehensive framework for environmental management accounting – links between business actors and environmental management account tools. Australian Accounting Review, 12(27), 39-50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Campbell, K., & Mínguez-Vera, A. (2008). Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 435-451

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carter, D.A., D’Souza, F., Simkins, B.J., Simpson, W.G. (2010). The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18(5), 396-414.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carter, D.A., Simkins, B.J., & Simpson, W.G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial Review, 38(1), 33-53.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cavalieri, E., & Franceschi Ferraris, R. (2010). Economia Aziendale. Attività e processi produttivi, Torino.

Cheng, S., Evans, J.H., & Nagarajan, N. (2008). Board size and firm performance: the moderating effects of the market for corporate control. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 31, 121-145.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Coles, J.L., Daniel, N.D., &Naveen, L. (2008). Boards: Does one size fit all?. Journal of Financial Economics, 87(2), 329-356.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cordazzo, M., & Marzo, G. (2020). Informativa non finanziaria dopo il D. Lgs. 254/2016. Evoluzione della normativa e implicazioni nelle pratiche aziendali. FrancoAngeli, Milano, 1-151.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dalton, D., Daily, C., Johnson, J., & Ellstrand, A. (1999). Number of directors and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 42(6), 674-686.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dalton, D.R., & Dalton, C.M. (2011). Integration of Micro and Macro Studies in Governance Research: CEO Duality, Board Composition, and Financial Performance. Journal of Management, 37(2), 404-411.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Andres, P.A., Azofra, V., & Lopez F. (2005). Corporate boards in some OECD countries: Size, composition, functioning and effectiveness. Corporate Governance. An International Review.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Donnelly, R., & Mulcahy, M. (2008). Board structure, ownership, and voluntary disclosure in Ireland. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(5), 416-429.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dutton, J.E., Dukerich, J.M., & Harquail, C.V. (1994). Organizational Images and Member Identification, Administrative Science Quarterly, 239-263.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eccles, R.G. (2013). Serafeim, the Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Harvard Business Review.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Edams, A. (2011). Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 621-640.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eisenberg, T., Sundgren, S., & Wells, M.T. (1998). Larger board size and decreasing firm value in small firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 48(1), 35-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Elshandidy, T., & Neri, L. (2015). Corporate governance, risk disclosure practices, and market liquidity: Comparative evidence from the UK and Italy. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(4), 331-356.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eng, L.L., & Mak, Y.T. (2003). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22(4), 325-345.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Erhardt, N.L., Werbel, J.D., & Schrader, C.B. (2003). Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance International Review, 11(2), 102-111.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Farrell, K.A., Hersch, P.L. (2005). Additions to corporate boards: The effect of gender. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1-2), 85-106.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Francoeur, C., Labelle, R. (2008). Sinclair-Desgagné, B. Gender diversity in corporate governance and top management. Journal of Business Ethics, 81, 83-95.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A., (2015). ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210-233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Friedman, M. (1970). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. New York Times Magazine.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gray, R.H., & Milne, M. (2002). Sustainability reporting: Who’s kidding whom?. Chartered Accountants Journal of New Zealand, 81(6), 66-70.

Greening, D.W., & Turban, D.B. (2000). Corporate Social Performance as A Competitive Advantage In Attracting A Quality Workforce. Business & Society, 39(3), 254-280.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guest, P.M. (2008). The determinants of board size and composition: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(1), 51-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guest P.M. (2009). The impact of board size on firm performance: evidence from the UK. The European Journal of Finance, 15(4), 385-404.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hermalin, B.E., Weisbach, M.S. (1988). The determinants of board composition. The Rand Journal of Economics, 589-606.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ho, S.S., & Wong, K.S. (2001). Study of the relationship between corporate governance structure and the extent of voluntary disclosure. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 10(2), 139-156.

Huther J. (1997). An empirical test of the effect of board size on firm efficiency. Economics Letters, 54(3), 259-264.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Iyengar, R.J., & Zampelli, E.M. (2009). Self-selection, endogeneity, and the relationship between CEO duality and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(10), 1092-1112.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jensen M.C. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. Journal of Finance, 48(3), 831-880.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jermias J., & Gani L. (2014). The impact of board capital and board characteristics on firm performance. British Accounting Review, 46(2), 135-153.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jizi, M., Nehme, R., & Salama, A. (2016). Do social responsibility disclosures show improvements on stock price? Journal of Developing Areas, 77-95.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Joecks, J., Pull, K., & Vetter, K. (2013). Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm performance: What exactly constitutes a “critical mass”? Journal of Business Ethics, 118, 61-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Johnson, R.A., & Greening, D.W. (1999). The Effects of Corporate Governance and Institutional Ownership Types on Corporate Social Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 564-576.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kassinis, G. (2006). Vafeas N, Stakeholder Pressures and Environmental Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 145-159.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, Y., Gong, M., Zhang, X.Y., & Koh, L. (2018). The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: The role of CEO power. British Accounting Review, 50(1), 60-75.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Linck, J., Netter, J., & Yang, T. (2008). The determinants of board structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 87(2), 308-328.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lipton, M., & Lorsch, J.W. (1992). A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Business Lawyer, 59-77.

Loderer, C., & Peyer, U. (2002). Board overlap, seat accumulation and share prices. European Financial Management, 8(2), 165-192.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lückerath, & Rovers, (2013). Women on boards and firm performance. Journal of Management and Governance, 17, 491-509.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Magnan, M., & Markarian, G. (2011). Accounting, governance and the crisis: Is risk the missing link? European Accounting Review, 20(2), 215-231.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mahadeo, J.D., Soobaroyen, T., & Hanuman, V.O. (2012). Board composition and financial performance: Uncovering the effects of diversity in an emerging economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 105, 375-388.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mc Williams, A., Siegel, D., & Wright, P.M. (2006). Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic Implications. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 1-18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Naciti, V. (2019). Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability e performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117727.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

O’Connell, V., & Cramer, N.(2010). The relationship between firm performance and board characteristics in Ireland. European Management Journal, 28(5), 387-399.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Palmer, K., Oates, W.E., & Portey, P.R. (1995). Tightening environmental standards: the benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 119-132.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2010). How Can Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Create Value for Stakeholders? A Systematic Review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39, 117-135.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rao, K., & Tilt, C. (2016). Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 138, 327-347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rechner, P.L., & Dalton D.R. (1991). CEO duality and organizational performance: A longitudinal analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 12(2), 155-160.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rodriguez Fernandez, M. (2016). Social responsibility and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance. Business Research Quaterly, 19(2), 137-151.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rose, C. (2007). Does female board representation influence firm performance? The Danish evidence. Corporate Governance an International Review, 15(2), 404-413.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Russo, M.V., & Fouts, P.A. (1997). A Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 534-559.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schnietz, K.E., Epstein, M. (2005). Exploring the Financial Value of a Reputation for Corporate Social Responsibility during a Crisis. Corporate Reputation Review, 7, 327-345.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sharma, S., Henriques, I. (2005). Stakeholder Influences on Sustainability Practices in the Canadian Forest Products Industry. Strategic Management Journal, 26(2),159-180.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sharma, S. (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 681-697.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shrader, C.B., Blackburn, V.B., & Iles, P. (1997). Women in management and firm financial performance: An exploratory study. Journal of Management Issues, 355-372.

Smith, N., Smith, V., & Verner, M. (2006). Do women in top management affect firm performance? A panel study of 2,500 Danish firms. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 55(7), 569-593.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sundarasen, S.D.., Je-Yen T., & Rajangam N. (2016). Board composition and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Corporate Governance International Journal of Business in Society, 16(1), 35-53.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Terjesen S., Sealy, R., Singh, V. (2009). Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 320-337.

Ullmann, A.E. (1985). Data in Search of a Theory: A Critical Examination of the Relationship’s among Social Performance, Social Disclosure and Economic Performance of US Firms. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 540-557.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yermack, D. (1995). Do corporations award CEO stock options effectively? Journal of Financial Economics, 39(2-3), 237-269.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yermack, D. (1996). Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of Directors. Journal of Financial Economics, 40(2), 185-211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-Jul-2023 Manuscript No. AAFSJ-23-13782; Editor assigned: 15-Jul-2023, PreQC No. AAFSJ-23-13782(PQ); Reviewed: 22-Jul-2023, QC No. AAFSJ-23-13782; Revised: 24-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-23-13782(R); Published: 29-Jul-2023