Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

The Influence of Corporate Governance Practices on Firm Sustainability Reporting Disclosure: Empirical Evidence from Malaysian Companies

Farah Amalin Mohd Noor, Universiti Teknologi Mara

Roshayani Arshad, Universiti Teknologi Mara

Nor Bahiyah Omar, Universiti Teknologi Mara

Ruhaini Muda, Universiti Teknologi Mara

Abstract

This study aimed to link the role of corporate governance practices on sustainability reporting disclosure for the top 100 Private Limited Companies (PLCs) in Bursa Malaysia. The study made use of the Legitimacy Theorem as a framework and content analysis. The study found that among the three (3) components of sustainability disclosure, the social theme had the most disclose provisions, while the economic theme had the least disclosure provisions. The study revealed that leadership commitment towards sustainability reporting results in better sustainable reporting disclosure. The findings showed that the larger a company is, the more likely it is to be subjected to public scrutiny, hence resulting in higher sustainability disclosures. However, there is a lack of evidence pertaining to the relationship between corporate governance and sustainability disclosure in Malaysia.

Keywords:

Corporate Governance, Malaysia, Firm Sustainability

Introduction

Sustainability reporting has become a common reporting practice adopted by companies to demonstrate their accountability. Sustainability reporting practices aim to fulfil the expectations and respond to pressure from the stakeholders for disclosure of information about social and environmental factors based on company activities (Boiral, 2013; Suttipun, 2015). In addition, issues on global climate change had raised public concerns on environmental issues which have increased societal expectations with regard to society, economics and the environment (Hossain et al., 2012). This escalating awareness among the stakeholders in the industry has led companies to be more vigilant in their decisions on the impact of business activities on society, and the environment as well as economics. Due to that, corporate governance practices in companies are important in order to improve a company’s offerings to be in line with stakeholders’ demands, and companies also need to be more socially and environmentally responsible, (Suttipun, 2015; Hasanudin, Yuliansyah, Said & Susilowati, 2019). After the Financial Crisis in 2008, transparency has become one of the important tools used to gauge good corporate governance (Amran & Ooi, 2014; Kazemian et al., 2021). According to (Mousa & Hassan, 2015), companies’ corporate governance practices gain legitimacy through the disclosure of social and environmental information to the public. (Lu & Abeysekera, 2014) asserted that companies with poor exposure on its social and environmental performance need to provide more disclosure and information on its activities, failing which it increases threats to a company’s legitimacy. Therefore, it can be said that corporate governance practices help legitimacy through disclosures in sustainability reporting (Mousa & Hassan, 2015)

Based on a survey by KPMG, over 80 percent of companies published sustainability reports worldwide (KPMG, 2008). The KPMG international survey indicated that sustainability reporting is going into more mainstream currency. Meanwhile, Ernst and Young’s beyond the Global 250 report further strengthened KPMG’s finding, when it reported that thousands of companies globally issued sustainability reports, and there is an upward trend in the number of companies doing so every year (EY, 2014). This is a strong indication that companies around the world have become more aware of the need to publish sustainability reporting and disclosure information on social and environmental factors related to a company activity.

Sustainability Reporting in Malaysia

In Malaysia, one of the initiatives undertaken by the government to promote sustainability engagement by local companies is by imposing a requirement for such information to be disclosed in the annual reports of Malaysian listed firms (The 2007 Budget Speech, 2006). In line with the government’s efforts to promote sustainability reporting amongst the listed firms, Bursa Malaysia i.e., the regulatory body of the capital market in Malaysia had issued a sustainability guideline for companies, which provides specific guidance on information that should be disclosed when making a sustainability statement in annual reports, as part of the compliance with the listing requirements (Bursa Malaysia, 2015). In addition, Bursa Malaysia, developed a comprehensive Corporate Social Reporting Framework in 2006. The framework provides guidance to companies in Malaysia on how to develop critical sustainability strategies and communicate those strategies to their stakeholders effectively. In brief, the framework focused on four (4) main areas of sustainability, namely marketplace, environment, community and workplace, and emphasizes on triple bottom-line advantages. Despite publishing a comprehensive framework, the companies were left riddled, as no clear requirements on what needs to be reported in the sustainable report concerning their sustainability activities. Subsequently, Bursa Malaysia issued another guideline on Sustainability Reporting in 2015, and imposed that all companies listed on the Main Market have to comply with the regulation by 2016 (Bursa Malaysia, 2015). Unlike the guidelines published earlier, the new guidelines provided a clearer picture on the disclosures that need to be incorporated in sustainability reporting.

However, there are companies which are more concerned with economic development, and view that sustainability initiatives become a burden as additional reporting can be expensive (Bertazzi, 2014; Dally, Rohayati & Kazemian, 2020). Hence, it is not surprising that (ACCA Singapore, 2013) stated that sustainability reporting becomes an issue in certain companies due to lack of management support. According to (D’Amato & Roome, 2009), competencies of people in top management can make an impact on organisational change. Whilst, the Legitimacy Theory asserts that in order for a company to still operate a business, it is important to remain legitimate with societal values and norms (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975). Hence, like it or not, companies have to abide to this new norm, as it appears that sustainability reporting is here to stay.

For a start, willingness by companies to disclose or publish sustainable reporting alone may be acceptable. However, what kind of information is being disclosed or published in a sustainable report is far more important as it will have an impact on various stakeholders. Hence, it is not surprising that the Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI, 2011) discusses the importance of external assurance in sustainability reports. Nevertheless, in the absence of such external assurance, stakeholders may depend on a company’s corporate governance practices. In fact, according to (Gnanaweera & Kunori, 2018), the development of sustainability reporting is one of the important theoretical perspectives for corporate governance practices in the Legitimacy Theory. Therefore, there is a possibility that companies with good corporate governance practices will be more willing to engage in sustainable practices, and subsequently make appropriate disclosure to their stakeholders. Due to this, elements such as the board of directors’ component and experiences and shareholding structures have some significant impact on a company’s sustainability reports. For instance, contributions of the board of directors’ to the direction of a company direction and performance is important. (Ahmad & Sulaiman, 2004; Nor et al., 2017) stated that a better company performance is strongly influenced by the board’s intellectual composition. The board’s engagement with company’s sustainability endeavours sends a strong message to company leaders and employees. As such, the board’s directions need to be aligned to its views on corporate sustainability (Jorgensen, 2014). Thus, the board’s commitment to sustainability is crucial in order to share same culture throughout the entire organisation, going beyond logic compliance, towards a real passion for sustainability (Salvioni et al., 2016). According to the Association of Certified Chartered Accountants (ACCA) Singapore (2013), the ownership of sustainability reporting needs to be linked with the board as it includes portraying the operation of the company as a whole. Meanwhile, corporate ownership contributes to the residual claims and decision control that give an impact on a company’s behaviour. According to (Haladu & Beri, 2016), ownership structure is important for sustainability information disclosure Although there are many studies made on the impact of company characteristics and external factors on the extent of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reporting, the impact of internal factors such as family involvement in ownership is inconclusive (Adams, 2002).

Sustainability reporting is a key mechanism for communicating sustainable performance and impacts to the stakeholders (GRI, 2011). It also acts as an assessment tool for possible risks to company activities which may have an impact on the environment and society (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005). A strand of studies discussed issues related to sustainability reporting in Malaysia. Issues such as pollution, waste, resources depletion, product quality and safety, the rights and status of workers and the power of larger corporations are amongst the issues which have become the focus of discussion and have gained attention and concerns by the stakeholders (Hussainey & Walker, 2009). Hence, in order to cope with such issues, sustainability engagement has become an important tool in addressing such matters. Such engagements in a way may also enhance a company’s corporate image, as well as improving their credibility by informing stakeholders about sustainability related activities undertaken by them (Pfau et al., 2008). In general, companies will gain competitive advantage when they are actively involved in sustainability activities, and subsequently reporting such activities to stakeholders, as such undertakings increase trust and goodwill of the stakeholders towards a company (Kolk & Pinkse, 2010). In addition, companies that actively engage in sustainability and reporting of sustainability issues may easily attract or retain excellent and talented employees, as employees are found to be attracted to work with employers who possess a good corporate reputation (Adams & Zutshi, 2004; Nor, Bhuiyan, Said, & Alam, 2017). Thus, it is important for companies to treat disclosure on sustainability as an integral part of their reporting responsibility. This study examined the relationship between corporate governance and sustainability reporting using the Legitimacy Approach. The remaining paper is organized as follows; Section 2 presents a review of the literature. Section 3 explains data collection procedures and the methodology used in the study. Next, Section 4 discusses the findings of the study. Finally, Section 5 concludes.

Literature Review

Legitimacy Theory and Sustainability Reporting Disclosure

Parsons (1960) defines legitimacy as “the appraisal of action in terms of shared or common values in the context of the involvement of the action in the social society”. Meanwhile Maurer (1971) views legitimation as a process whereby an organization justifies to a peer or a superordinate system its right to exist; that is to continue, import, transform and export energy, material or information. (Preston & Post, 1975) points out that legitimacy is the combination of institutional actions and social values, and legitimization as actions that institutions take either to signal value congruency or to change social value. In essence, legitimacy can be achieved by linking company activities with acceptable social values.

The Legitimacy Theory also stresses the importance of societal acceptance in ensuring a company’s survival (Deegan, 2002). The basic foundation of this theory is the belief that a company’s activities are seen to have an impact on the environment in which it operates. Hence, sustainability disclosures in this situation can be used or are exploited to justify a company’s continued existence. This theory further posits that companies are continually seeking ways to ensure that they operate within the bounds and norms of society (Deegan, 2000). This is important as the a company may lose its operation licenses if it breaches societal norms and expectations (Jung et al., 2012). Legitimacy of a company is achieved when they show that their activities comply with social values (Martínez et al., 2016). Thus, a company must act in favour of what a society has established and disclosing the measures that were taken in order to adhere to societal needs. According to (Vogt et al., 2017), the Legitimacy Theory is a tool that interprets studies on the reporting and on the environmental performance of companies. Many studies have used this Theory to interpret and explain the reactions of companies to assess any threats to their legitimacy (Martínez et al., 2016; Vogt et al., 2017).

The Legitimacy Theory is derived from the concept of organizational legitimacy that has been defined by (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975) as “a condition or status which exists when an entity’s value system is congruent with the value system of the larger social system of which the entity is a part”. According to (Chu et al., 2012), the Theory is capable of describing social acceptance of companies. Simply put, the Legitimacy Theory ensures that organizations continually operate within the bounds and norms of respective societies. In order to secure their legitimacy, companies need to inform their stakeholders of the improvement they intend to do on company performance, finding ways to distract stakeholders from certain issues, changing stakeholders’ perception regarding certain events and changing expectations of external stakeholders on company performance (Lindblom, 1994). Therefore, accounting is a legitimating institution and provides the means by which social values are linked to economic actions of a given company (Richardson, 1987).

The scope of the Legitimacy Theory is based on the belief that managers will undertake necessary strategies to prove to society that they are complying with the expectations of a said society. According to (Chan et al., 2014), companies must keep pace with the constant changes in societal values in order to make society believe that they are good corporate citizens, operating a business legitimately. This theory also pertains that an organization would voluntarily report on its activities if management perceives that those activities are expected by the communities in which they operate in (Deegan, 2002). Based on prior research, in order to ensure legitimacy, companies tend to limit the disclosures to only good news (Milne et al., 2009).

The growing accounting research in social and environmental reporting areas are usually focused on studies concerning the extent and determinants of social voluntary disclosure (Nurhayati et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2012). There are also several other studies which directly or indirectly examine the Legitimacy Theory and its applicability to sustainability disclosure practices of companies (Deegan, 2002; Chan et al., 2014; Shanmugam, 2017). In the context of this study, it is inferred that the Legitimacy Theory shall demonstrate that companies will only disclose mandatory information required to show that their operations are legitimate, or they are behaving as good corporate citizens.

Corporate Governance Practices and Sustainability Reporting Disclosure

The Legitimacy Theory has been used in various studies in corporate governance (Fauziah et al., 2012). According to (Martínez et al., 2016), the legitimacy of a company is achieved when it shows that company activities comply with social values. Companies also seek to establish congruency between social values associated with their activities and the norms of acceptable behavior in the larger social system of which they are a part to justify their legitimacy (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975). As society in a way owns the use of natural resources and provides supply of labor, a company implicitly needs permission from it to operate its business, and ultimately becomes accountable to the society on how it operates and what it does.

From the perspective of the Legitimacy Theory, disclosures of financial and non-financial information involve a relationship between a company and its managements. It provides information on company activities that help to legitimize its behavior which leads to change perceptions and expectations of stakeholders (Adams & González, 2007; Adams & McNicholas, 2007). Meanwhile, good governance refers to the legitimate, accountable and effective ways of obtaining and using public power and resources in the pursuit of widely accepted social goals (Johnston, 2009). According to (Keping, 2017), the function of governance is to guide and regulate activities through various authoritative systems and to maximize public interests. Therefore, good corporate governance practices and sustainability disclosure can be seen as a complementary mechanism of legitimacy that companies use to communicate with stakeholders.

Company activities which provide benefits to society will normally gain support from its stakeholders. Hence, the board of directors plays a vital role in establishing strategies that legitimize company behavior, which includes accommodating sustainability reporting (Khan et al., 2013). According to (Weber & Schweiger, 1992), the board of directors’ commitment and exposure towards sustainability reporting sends a positive message to the employees of the companies and contribute to efficiency of the reporting, thus advocating the Legitimacy Theory. In addition, the board of directors which has the right skills, attitudes, knowledge and values, especially if they have experience working abroad, may contribute to the success of organizational reporting.

Within the Legitimacy Theory Framework, sustainability disclosure is meant as a company’s response toward public pressure, in an attempt to prove that a company’s behavior is in line with societal norms and values (Freeman, 2004). In brief, the Legitimacy Theory provides a useful framework to examine social and environmental disclosure as a response to the expectation to particular stakeholder groups (Deegan, 2002). The Legitimacy Theory has been widely used in prior research to describe the fulfillment of environmental and social disclosures (Campbell, 2003). According to (Gray et al., 1995) the Legitimacy Theory has an advantage over other organizational and management theories as it explains the disclosing strategies that companies may use to legitimate their existence, which are can be empirically tested. Apart from that, the ownership structure of a company is also one of the important factors which can influence a company’s corporate governance system and practices. In summary, the legitimacy theory asserts that corporate governance is vital in contributing to an enhancing disclosure by companies.

Malaysia has its own corporate governance legislation and guidelines in order to cope with corporate scandals in as Enron, WorldCom and Satyam as well as to enhance and guide corporate governance (Bhatt, 2016). The main sources of the corporate governance reform agenda in Malaysia are from the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance (MCCG) by the Finance Committee on Corporate Governance, Capital Market Master Plan (CMP) by the Securities Commission and Financial Sector Master Plan (FSMP) by Bank Negara Malaysia for the financial sector. A high-level finance committee on corporate governance published a comprehensive report which formed the basis of corporate governance reforms in Malaysia in 1999. The MCCG applies to all public listed companies, which are required to disclose compliance with the MCCG in its annual reports. MCCG 2012 supersedes the 2007 Code and it sets out the broad principles and specific recommendations on structures and processes that companies should undertake to be good at corporate governance as an integral part of their business culture.

Corporate governance is, therefore, about what the board of the company does and how it sets the value of the company and it is to be distinguished from the day-to-day operational management of a company by its full-time executives. As mentioned earlier, the Legitimacy Theory is a useful mechanism that provides recognition of the companies to their stakeholders. Therefore, this study used the Legitimacy Theory as the underlying theoretical perspective to explain the disclosure characteristics of sustainability reporting among the top 100 Public Listed Companies (PLC) at Bursa Malaysia that were published for the 2016 financial year.

Hypotheses Development

The study examined the components of corporate governance- the board and ownership structure. In the case of the board, this study focused on international experience and top management culture. In addition, the study focused on two ownership structures that is family ownership and government ownership. MCCG (SSM, 2012) focused on the role of the board in providing leadership, enhancing board effectiveness through strengthening its composition and reinforcing its independence. Thus, international experience of the board of directors related to knowledge, skills and human capital and the prevalent top management culture were included.

International Experience

International experience refers to a person who has worked and travelled abroad and who probably has been in a good role that has an international focus (British Council, 2015). (Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2011; Rahim et al., 2017) used the term human capital efficiency that includes international experience as one factor of the human capital. Consistent with the Legitimacy Theory, the board of directors of organizations which has skills, attitudes, knowledge and values from overseas could contribute to the success of organizational reporting.

The board of directors is believed to have a relationship with the performance of a company and the extent of sustainability disclosures. A board of directors with international experience can be considered to have an edge over others because of the experience and knowledge gained while working and living in other countries. Prior literature has provided empirical evidence that there is significant positive relationship between human capital among boards and corporate sustainability reporting disclosure. In summary, studies have highlighted that international experience has a positive effect on financial performance. In addition, (Carpenter & Fredrickson, 2011) found that a Chief executive officer with proven international experience will have a positive and consistent impact on company performance. They concur that CEOs with international experience have broader perspectives as they have been exposed to international complexities and worldviews. Yeoh (2004) also argued that international experience gained by CEOs allows them to achieve success in managing a company. Additionally, they were able to adapt quickly in securing opportunities including emerging ones as they are experienced in analyzing internal as well as external information collated, as well as strategize and execute business plans better than their peers. (Slater & Fowler, 2009) found evidence of a positive relationship between a board with international experience and corporate sustainability reporting performance. They argued that awareness of broader stakeholder expectations will be gained when the boards have international assignment experience and, at the same time, apply their personal values to act in society’s interest which leads to taking proactive CSR initiatives and results in a positive impact on sustainability performance. According to (Rivas, 2012), executives who have international experience are more prepared to face challenges and consequently would produce positive effects on their strategic actions and decisions. In summary, based on the above arguments, it is deduced that international experience plays a critical role in ensuring the enhancement of sustainability disclosure in companies. This infers that international experience may potentially have a positive effect on sustainability disclosure. Hence, the first hypothesis is:

H1: There is significant positive relationship between international experience and sustainability disclosure.

Top Management Culture

Top management culture relates to the responsibility of top management in companies to exhibit good leadership support and commitment which is seen to lead to superior company disclosures and performance. The Legitimacy Theory proposes that leadership commitment and exposure towards sustainability reporting sends a positive message to the employees of companies and can contribute to efficiency of reporting (Weber & Schweiger, 1992). Top management is more likely to exhibit sustainability behaviors if they possess corporate commitment to sustainability. Studies by (Bardeleben, 2011; Yahya & Ha, 2014) show that leaders who support sustainability disclosures will enhance their prospect of achieving strategic goals. Leadership engagement and commitment from top management will lead to good disclosures. (Huafang & Jianguo, 2007) argued that board commitment has a positive significance to company disclosure. D’Amato & Roome (2009) also indicated that companies create more commitment through leadership practices for sustainability. Thus, top management is more likely to feel positive about their company if they are committed to sustainability. (Cameron & Quinn, 2006) also found a positive relationship between the successes of a firm and organizational culture. Organizational culture refers to the culture that leaders bring into an organization. Likewise, Asree, et al., (2010) also found similar results in their study regarding competency of the leadership, responsiveness and organizational culture influence a firm’s performance. From these arguments it is inferred that top management culture may potentially have a positive effect on sustainability disclosures. Thus, the following is hypothesized:

H2: There is significant positive relationship between top management culture and sustainability disclosure.

Family Ownership

A strand of studies has examined the relationship between family ownership and sustainability disclosures. The purpose of those studies was mainly to examine whether the existence of sustainability reporting initiatives has been influenced by family ownership. Prior literature has registered many studies on the relationship between financial performance and family ownership structure as well as on financial and corporate socially responsible disclosure. However, there is still lack of studies discussing sustainability reporting disclosures.

Most of the studies on accounting disclosure agree that corporate disclosure is influenced by ownership structure (Ghazali, 2007). Related scholarly and practitioner reports have indicated that family ownership has a high control of corporate disclosure compared to non-family firms (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005; Ghazali, 2007; Amran & Ahmad, 2013; Habbash, 2016). However, Haniffa & Cooke (2005) found that family ownership is less likely to disclose information voluntarily. (Pérez & Marín, 2017) stated that family-owned companies also contain unique characteristics derived from patterns of ownership, governance and succession which influence organizational value and belief systems such that family firms may differ from non-family firms. In relation to the Legitimacy Theory, family ownership can achieve company activities linked to social values.

Furthermore, according to (Berrone et al., 2012) family ownership is more concerned with protecting and enhancing the image and reputation of a company. It is because family ownership is committed to the prevention of social concerns in terms of damage to the interest groups (Dyer & Whetten, 2006). Overall, the family ownership literature suggests that family ownership particularly seeks legitimation for their actions and thus, they try to meet shareholders’ interests in terms of social and environmental preservation (Berrone et al., 2012). Family members on the board have the power to monitor other managers from expropriating company wealth. This is consistent with the study by (Lin & Chang, 2011) that argued that such power leads to better performance of companies as well as better disclosure. However, the study by (Chau & Gray, 2002) on ownership structure and voluntary disclosure in companies in Hong Kong and Singapore revealed that outside ownership is positively associated with voluntary disclosure while family owned in companies have less impact on the level of disclosure. Chen, et al., (2008) stated that family-owned companies have a large, concentrated equity holding and are less diversified; hence, they are more into internalizing both the benefits of voluntary disclosure and cost of non-disclosure.

Based on the above arguments, this study examined this issue within the context of high family influence in companies. The researcher believes that family ownership could gain several social benefits from their shares in the company in addition to financial gains such as building a strong social image, prestige, good reputation and social position for their families. At same time it should result in a greater concern to society as well as high disclosure in sustainability reporting. Hence, the following is hypothesized.

H3: There is significant positive relationship between family ownership and sustainability disclosure.

Government Ownership

Government ownership refers to the proportion of government investment in a company. It serves as a control mechanism for a company (Ahmad et al., 2008) and promote accountability and transparency of company disclosures (Kazemian, Rahman, Ibrahim & Adeymi, 2014). A strand of studies asserts that government ownership in a company has an impact on voluntary disclosure. For example, (Eng & Mak, 2003) found a significant positive relation between government ownership and voluntary disclosure. It is evident that government-controlled companies have greater communication with other stakeholders which leads to an increase in disclosure. (Ghazali, 2007) investigated the influence of ownership structure on corporate social responsibility disclosure in Malaysia. He found that companies in which the government has a substantial ownership disclosed significantly more information. It implies that since government-owned companies are constantly in the public eye, they are expected to be transparent and more information should be disclosed. In addition, public companies that are politically supported by the government, disclosed more social and environmental information to be seen as ‘legitimate’ (Cormier & Gordon, 2001). Hence, the Legitimacy Theory would predict that companies that have government ownership would disclose more sustainability information to show their accountability to the citizens.

Sepasi, et al., (2016) found that there is no relationship between government ownership and disclosure quality. Furthermore, (Ghazali & Weetman, 2006) also found no significant association between government ownership and the extent of voluntary disclosure in Malaysia. The study asserted that government- controlled companies which are strongly politically associated tend to disclose less information to protect their beneficial owners. However, this study argues that government ownership could effectively influence society and give pressure to disclose additional information to be accountable to the public as a whole. Thus, government ownership could promote good governance, social responsibility and disclosure practices, hence, the following is hypothesized.

H4: There is significant positive relationship between government ownership and sustainability disclosure.

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

The sample was drawn from the population of listed companies in the main board of Bursa Malaysia based on the categories of industries, namely, consumer products, industrial products, trading/services industries, construction, plantation and property. However, companies in the financial industry were excluded in the study due to their high leverage and the fact that they differ from non-financial companies as is the common practice in research. The data set was obtained from the Annual reports and Sustainability reports of the top 100 public listed companies for the financial year ending in 2016 using content analysis. Content analysis is a preferred and dominant method used in previous studies to assess voluntary disclosure in annual reports. This method has been used in studies on capital market, sustainability disclosure and CSR reporting such as in (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012; Gavana et al., 2017).

Measurement of Variables

The study made use of the Sustainability disclosure Index based on Sustainable Disclosure themes by (Bursa Malaysia, 2015; GRI, 2011). Table 1 presents the measurement of variables used in the study. The data set was examined to determine type of disclosure into 3 main themes using the thematic labels Economic, Environment and Social. Each theme represented different amounts of construct characteristics, for example, the economic theme was measured by three (3) constructs; environment and social themes were measured with ten (10) constructs. In total there were twenty-three (23) construct parameters. The scoring of each themes in the sustainability disclosures were calculated based on the measurement of the criteria met. The score of one (‘1’) was be assigned on the criterion met, and a score zero (‘0’) assigned if the criterion was not met. The first element in sustainability disclosure is economics which refers to company’s disclosure on the impact of economic conditions to their stakeholders, as well as to economic systems at local, national and global levels (Bursa Malaysia, 2015). The three (3) main factors that focused on the economic theme were elements of procurement practices, community investment and indirect economic impact. Second, the environmental theme referred to a company’s impact on the natural ecosystem. The environmental theme also included a company’s usage of energy and water, biodiversity, discharge of emissions, supply chain products and services responsibility, compliance of environmental activities to relevant laws and guidelines as well as components used as input in the production of goods. Third, the social theme measured information on the impact that the company created on the social systems. This included assessment on a company’s relationship with the communities, employees and consumers. Finally, the study included organizational size as a control variable.

| Table 1 Summary of Variable Measurement |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Description of Measurement | Sources |

| Sustainability Disclosure | Self-constructed sustainability disclosure | Sustainability Reporting |

| Sustainability index, Ij | (Shanmugam, 2017) | |

| =?nXij x 100 | (Bursa Malaysia, 2015) | |

| 23 | (GRI, 2011) | |

| Whereby, | ||

| n=Number of indicators disclosed | ||

| Xij=1 if the indicator is disclosed and ‘0’ if otherwise | ||

| Dichotomous scores of ‘1’, if sustainable and ‘0’ if otherwise. | ||

| International Experience | IEX=The percentage of boards with international experience | Boards’ Profile in companies’ annual reports. |

| (Bronco and Rodriques, 2008) | ||

| Top management culture | TMC=available information by top management that support the disclosure of sustainbility activities. | Companies’ annual reports in CEO’s statement and Sustainability Reporting, |

| (Rodríguez-Ariza et al., 2012) | ||

| Dichotomous scores whereby score of “1” is given if the CEO/managing directors/Chairman’s reviews are related to the sustainability disclosure and score of “0” if otherwise | ||

| Family Ownership Structure | FAM=Total percentage of family members on board to total number of board members | Companies’ annual reports. |

| (Habbash, 2016) | ||

| Government Ownership Structure | GOV=Total percentage of shares owned by government to total number of shares issued | Companies’ annual reports, (Aman et al., 2006) |

| Organizational Size | SIZE=Natural log of total asset of company | Annual Reports |

| (Juhmani, 2014) | ||

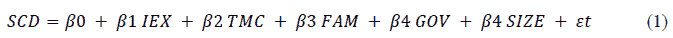

This study applies regression analysis to test the hypotheses as follows:

SCD is sustainability disclosure

IEX is international experience

TMC is top management culture

FAM is family ownership structure

GOV is government ownership structure

SIZE is organization’s size

εt is error term

The study applied a standard multiple regression to explore the predictive ability of a set of variables (Pallant, 2011), to test relationships between corporate governance practices and sustainability disclosure of the top 100 Private Limited Companies (PLCs) in Bursa Malaysia for the financial year ending in 2016.

Results and Discussion

Reliability and Validity of Content Analysis

In order to ensure the reliability of sustainability disclosure of the top 100 public listed companies in Bursa Malaysia for the year ending in 2016, Cronbach’s coefficient was used as mean to measure the internal consistency of the data samples. Internal consistency of data refers to the consistent scores across the measurement. Aside from that, the measure of reliability of sustainability disclosure was undertaken to ensure that the data was measured precisely and accurately. The values ranged from zero (0) to one (1), with higher values indicating higher reliability. It was recommended that the minimum level of 0.7 Cronbach’s alpha be used to indicate reliability of the sustainability disclosure (Pallant, 2011).

Based on Table 2, the value of Cronbach’s alpha for the overall scale was 0.828. The value indicated that internal consistency of the reliability on all 23 scaled items were consistent. According to George & Mallery (2003), as a rule of thumb, Cronbach’s alpha at a minimum level of 0.8 to 0.89 indicated that the samples are in good consistency. Thus, based on the results, the data samples collected on the content analysis were of good quality.

| Table 2 Reliability Statistics |

||

|---|---|---|

| Cronbach's Alpha | Cronbach's Alpha Based on Standardised Items | N of Items |

| 0.828 | 0.828 | 23 |

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics for the sustainable disclosure score for the top 100 public listed companies. The mean value of 18.12 indicated that in average the sustainable disclosure score of the companies was above the median. For components of sustainability disclosure, all three components showed mean values above the median values. For the economic component, the minimum value of 0.00 for the sustainability disclosure indicated that there is no improvement on the sustainability disclosure for some companies even though mandatory sustainability reporting has been imposed by the regulatory body since 2015. The maximum value of 3 for the sustainability disclosure on the economic perspective infers that there were full scores for sustainability disclosure on the economic theme for some companies based on the Bursa Malaysia Sustainability Disclosure. This indicated that a majority of the top 100 public listed companies on Bursa Malaysia had the economic sustainability disclosure item in their sustainability disclosure. From the Environment perspective, the minimum value of 2 indicated that there were at least two information on the environment that have been disclosed by some of the companies in compliance with sustainability reporting imposed by Bursa Malaysia. A maximum value of 10 for the sustainability disclosure from the environment perspective inferred that there were full scores for some companies. It can be inferred that the public listed companies are able to adjust their activities with the changes in the environment in order to ensure that sustainability is achieved in the future. Meanwhile from the social perspective, most companies were able to adapt to sustainability disclosure. The minimum value of 4 indicated that at least four items have been disclosed by some companies from the social perspective in compliance with the guidelines set by Bursa Malaysia Sustainability Disclosure. The maximum value of 10 shows that there were full scores for the social perspective in the sustainability disclosure.

| Table 3 Descriptive Statistics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Sustainability Disclosure score | 8 | 23 | 18.12 | 3.99 |

| Components of sustainability disclosure | ||||

| Economic | 0 | 3 | 2.35 | 0.9 |

| Environment | 2 | 10 | 7.38 | 2.17 |

| Social | 4 | 10 | 8.39 | 1.63 |

| International experience | 0 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.21 |

| Top management culture | 0 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Family ownership structure | 0 | 0.63 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| Government ownership structure | 0 | 0.95 | 0.12 | 0.18 |

| Size of companies | 5.09 | 8.02 | 6.44 | 0.61 |

Among these three components, the economic perspective in the sustainability guidelines by Bursa Malaysia scored the lowest mean at 2.35 and a minimum value of 0. This highlights that the top 100 public listed companies in Bursa Malaysia need to give more attention to the economic perspective in their sustainability reporting.

Multivariate Test

This study used the multiple regression method in pursuing multivariate analysis. The multiple regression results in Table 4 shows the extent varying on the degree of regression coefficient at a different variable in the model.

| Table 4 Regression Results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Sustainability Reporting Disclosure | ||

| Model | Beta | t | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 0.388 | 0.7 | |

| Size of companies | 0.353* | 3.554 | 0 |

| International experience | -0.065 | -0.68 | 0.5 |

| Top management culture | 0.208** | 2.053 | 0.04 |

| Family ownership structure | -0.073 | -0.76 | 0.45 |

| Government ownership structure | -0.05 | -0.51 | 0.61 |

| R square | 0.211 | ||

| Adjusted R square | 0.169 | ||

| F | 5.027 | ||

| Sig | 0 | ||

| **Significant at 5% level (1-tailed test) * Significant at 1% level (1-tailed test) | |||

Table 4 shows that the adjusted R-squared is 0.211 with a F value of 5.027. Therefore, these values provide evidence that the model in this study was valid. The results indicated that the size of the organization and top management culture have a significant positive relationship with sustainability reporting disclosure at the 1% and 5% level of significance. The result affirms that the control variable that is company size has a relationship with sustainability reporting and disclosure, as found in (Ghazali, 2007).

Discussion of the Findings

Table 5, presents a summary of conclusions for the hypotheses developed in the study. There were four hypotheses developed to test the relationship between corporate governance practices and sustainability reporting disclosure for the top 100 companies listed at Bursa Malaysia for the financial year ending 2016. The study had identified the sustainability reporting disclosure score to link with the four components of corporate governance practices. Sustainability reporting disclosures were measured based on the information disclosed in their respective annual reports and/or sustainability reports, as some public listed companies prepare an integrated sustainability report. The evaluations of the sustainability reporting published by the public listed companies focused on four (4) themes, classified as community, environment, workplace and marketplace based on the classifications by (Bursa Malaysia, 2015; GRI, 2011). Meanwhile, the evaluation on corporate governance characteristics of the public listed companies focused on four (4) attributes, namely international experience, top management culture, family ownership and government ownership as suggested in the literature of corporate governance and the Legitimacy Theory.

| Table 5 Summary of Hypotheses Tests |

||

|---|---|---|

| Components of Corporate governance practices | Hypotheses | Sustainability reporting disclosure |

| International experience | H1 | Rejected |

| Top management culture | H2 | Failed to reject |

| Family ownership structure | H3 | Rejected |

| Government ownership structure | H4 | Rejected |

The statistical inferences suggest that H2 is not rejected at the 5% level of significance. Whilst H1, H3 and H4 were rejected at the 5% level of significance. The study found that there is a significant positive relationship between top management culture and the sustainability disclosure score (H2). The boards’ commitments to developing the culture in companies lead to a comprehensive disclosure of sustainability information (Huafang & Jianguo, 2007; Weber, 2006). In fact, the ability of top management to focus on the commitment on sustainability reporting disclosure will enhance sustainability reporting disclosure of the companies (Yahya & Ha, 2014). Top management support has been found to be an important factor for the successful integration of a standard (Young & Jordan, 2008). The finding revealed that leadership commitment towards sustainability reporting results in better sustainable reporting disclosure.

Meanwhile, the results also showed that there was no significant relationship sustainability reporting disclosure with the three components of corporate governance: namely, international experience, family ownership and government ownership. The study revealed that international experience has an insignificant relationship with sustainability disclosure. In addition, H3 predicted that family ownership has a significant positive impact on sustainability disclosure of public listed companies. (Chen et al., 2008) found that family-owned companies, i.e., which have large, concentrated equity holdings and are less diversified, have a higher sustainability reporting content. Though the relationship observed was positive, family ownership did not significantly encourage sustainability disclosure. This result is consistent with findings by (Ghazali, 2007) that companies with a concentrated family ownership tend to have a high degree of control on corporate disclosure matters as compared to nonfamily-owned companies, hence providing less disclosure. H4 predicted that government ownership has a significant positive impact on sustainability disclosure by public listed companies. A study by (Eng & Mak, 2003) found a significant positive relation between government ownership and voluntary disclosure. On the contrary, the result revealed contradict that the relationship between government ownership and sustainability disclosure in the public listed companies was insignificant.

In summary, the findings infer that the larger a company is, the more likely it is to be subjected to public scrutiny, hence resulting in higher sustainability disclosures. This result is consistent with the posits of the Legitimacy Theory that larger companies tend to disclose more social and environmental information to meet the expectations of society (Lu, 2014). Top management culture also promotes comprehensive information in sustainability reporting disclosure. However, other corporate governance components had no significant influence on sustainability reporting disclosure. It implies that there is a lack of evidence pertaining to the relationship between corporate governance and sustainability disclosure, particularly in developing countries. The legitimacy literature views that culture, beliefs and commitment of the boards play a crucial role in advancing the quality of corporate socially responsible disclosures.

Conclusion

- ACCA Singapore. (2013). The business benefits of sustainability reporting in singapore: ACCA Sustainability Roundtable Dialogue on 24 January 2013. Singapore: ACCA Singapore.

- Adams, C.A. (2002). Internal organizational factors influencing corporate social and ethical reporting: Beyond current theorizing. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(2), 223-250.

- Adams, C.A., & González, C.L. (2007). Engaging with organizations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting and performance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 333-355.

- Adams, C.A., & McNicholas, P. (2007). Making a difference: Sustainability reporting, accountab-ility and organizational change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 382-402.

- Adams, C.A., & Zutshi, A. (2004). Corporate social responsibility: Why business should act responsibly and be accountable. Australian Accounting Review, 14(34), 31-39.

- Ahmad, R., Aliahmed, H.J., & Razak, N.H.A. (2008). Government ownership and performance: An analysis of listed companies in Malaysia.

- Aman, A., Iskandar, T.M., Pourjalali, H., & Teruya, J. (2006). Earnings management in Malaysia: A study on effects of accounting choices. Management & Accounting Review, 5(1), 185-209.

- Amran, N.A., & Ahmad, A.C. (2013). Effects of ownership structure on Malaysian companies’ performance. Asian Journal of Accounting & Governance, 4, 31-60.

- Amran, A., & Ooi, S.K. (2014). Sustainability reporting: Meeting stakeholder demands. Strategic Direction, 30(7), 38–41.

- Asree, S., Zain, M., & Razalli, M.R. (2010). Influence of leadership competency and organizatio-nal culture on responsiveness and performance of firms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(4), 500-516.

- Berrone, P., C Cruz, C., & Mejía, L.R.G. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279.

- Bertazzi, P. (2014). Cost and burden of reporting.

- Bhatt, P.R. (2016). Corporate governance in Malaysia: Has MCCG made a difference. International Journal of Law and Management, 58(4), 403–415.

- Boiral, O. (2013). Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(7), 1036-1071.

- British Council. (2015). A world of experience: How international opportunities benefit individuals and employers, and support UK Prosperity.

- Bursa Malaysia. (2015) Sustainability reporting guide. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Bursa Malaysia.

- Campbell, D. (2003). Intra‐ and intersectoral effects in environmental disclosures: Evidence for legitimacy theory? Business Strategy and the Environment, 12(6), 357-371.

- Carpenter, M.A., & Fredrickson, J.W. (2011). Top management teams, global strategic posture, and the moderation role of uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 533–546.

- Chau, G.K., & Gray, S.J. (2002). Ownership structure and corporate voluntary disclosure in Hong Kong and Singapore. The International Journal of Accounting, 37, 247-265.

- Chu, C.L., Chatterjee, B., & Brown, A. (2012). The current status of greenhouse gas reporting by Chinese companies. Managerial Auditing Journal, 28(2), 114–139.

- Chen, S., Chen, X., & Cheng, Q. (2008). Do family firms provide more or less voluntary disclosure? Journal of Accounting Research, 46(3), 499–536.

- Cameron, K.S., & Quinn, R.E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

- Chan, M.C.C., Watson, J., & Woodliff, D. (2014). Corporate governance quality and CSR disclosures. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(1), 59–73.

- Cormier, D., & Gordon, I.M. (2001). An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(5), 587-617.

- D’amato, A., & Roome, N. (2009). Leadership of organizational change toward an integrated model of leadership for corporate responsibility and sustainable development: A process model of corporate responsibility beyond management innovation. Unpublished dissertation, Universite Libre de Bruxelles.

- Dally, D., Rohayati, Y., & Kazemian, S. (2020). Personal carbon trading, carbon-knowledge management and their influence on environmental sustainability in Thailand. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 10(6), 609-616.

- Deegan, C. (2002). Introduction: The legitimizing effect of social and environmental disclosures – A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282-311.

- Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social value & organizational behavior. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122-136.

- Dwivedi, S., Kaushik, S., & Luxmi. (2014). Impact of organizational culture on commitment of employees: An empirical study of BPO Sector in India. Vikalpa, 39(3), 77–92.

- Dyer, W.G., & Whetten, D.A. (2006). Family firms and social responsibility: Preliminary evidence from the S&P 500. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 785-802.

- Eng, L.L., & Mak, Y.T. (2003). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22(4), 325–345.

- EY. (2014). Value of sustainability reporting: A Study by EY and Boston college center for corporate citizenship. United States: EY and The Carroll School of Management Center for Corporate Citizenship at Boston College.

- Freeman, R.E. (2004). The stakeholder approach revisited. Journal of Business and Business Ethics, 5(3), 228–241.

- Gavana, G., Gottardo, P., & Moisello, A.M. (2017). The effect of equity and bond issues on sustainability disclosure. Family vs non-family Italian firms. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(1), 126–142.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step-by-step: A simple guide and reference, 14.0 update (7th Edition). Boston, United States: Allyn & Bacon.

- Ghazali, N.A.M. (2007). Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Some Malaysian evidence. Corporate Governance, 7(3), 251-266.

- Ghazali, N.A.M., & Weetman, P. (2006). Perpetuating traditional influences: Voluntary disclosure in Malaysia following the economic crisis. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 15(2), 226-248.

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). (2011). Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, Version 3.1. The Netherlands: Global Reporting Initiative.

- Gnanaweera, K., & Kunori, N. (2018). Corporate sustainability reporting: Linkage of corporate disclosure information and performance indicators. Cogent Business & Management, 5(1), 1-21.

- Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2), 47-77.

- Habbash, M. (2016). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Social Responsibility Journal, 12(4), 740-754.

- Haladu, A., & Beri, M.H. (2016). Corporate characteristics and sustainability reporting environm-ental agencies’ moderating effects. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 21(8), 19–30.

- Haniffa, R., & Cooke, T.E. (2005). The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(5), 391–430.

- Hasanudin, A. I., Yuliansyah, Y., Said, J., & Susilowati, C. (2019). Management control system, corporate social responsibility, and firm performance. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 6(3), 1354-1366.

- Hossain, M., Rowe, A., & Quaddus, M. (2012). The current trends of Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting (CSER) in Bangladesh. Proceedings of 11th Australasian Centre for Social and Environmental Accounting Research (A-CSEAR) Conference, Australia: University of Wollongong.

- Huafang, X., & Jianguo, Y. (2007). Ownership structure, board composition and corporate voluntary disclosure: Evidence from listed companies in China. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(6), 604-619.

- Hussainey, K., & Walker, M. (2009). The effects of voluntary disclosure and dividend propensity on prices leading earnings. Accounting Business Research, 39(1), 37-55.

- Jorgensen, H.B. (2014). 5 ways boards of directors can support sustainability.

- Johnston, M. (2009). Good governance: Rule of law, transparency, and accountability.

- Juhmani, O. (2014). Determinants of corporate social and environmental disclosure on websites: The case of Bahrain. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance, 2(4), 77 – 87.

- Jung, T., Miller, M.J., Palmer, T.N., & Wedi, N. (2012). High-resolution global climate simulations with the ECMWF model in project Athena: Experimental Design, Model Climate, and Seasonal Forecast Skills. Journal of Climate, 25(9), 3155-3172. Kazemian, S., Djajadikerta, H. G., Said, J., Roni, S. M., Trireksani, T., & Alam, M. M. (2021). Corporate governance, market orientation and performance of Iran’s upscale hotels. Tourism and Hospitality Research, https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584211003644

- Kazemian, S., Rahman, R. A., Ibrahim, Z., & Adeymi, A. A. (2014). AIM's Accountability in Financial Sustainability: The Role of Market Orientation. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 5(2), 191-194.

- Keping, Y. (2017). Governance and good governance: A new framework for political analysis. Fudan. Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 11, 1–8.

- Khan, A., Muttakin, M.B., & Siddiqui, J. (2013). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 207-223.

- Kolk, A., & Pinske, J. (2010). The integration of corporate governance in corporate social responsibility disclosures. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Managem-ent, 17(1), 15-26.

- KPMG. (2008). KPMG international survey of corporate responsibility Reporting 2008.

- Lin, F.L., & Chang, T. (2011). Does debt affect firm value in Taiwan? A panel threshold regression analysis. Applied Economics, 43(1), 117-128.

- Lindblom, C.K. (1994). The implication of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. Proceedings of Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, University of St Andrews.

- Lu, Y., & Abeysekera, I. (2014). Stakeholders' power, corporate characteristics, and social and environmental disclosure: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 64, 426-436.

- Maurer, J.G. (1971). Readings in organizational theory: Open system approaches. New York: Random House.

- Michelon, G., & Parbonetti, A. (2012). The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. Journal of Management and Governance, 16(3), 477–509.

- Martínez, J.B., Fernández, M.L., & Fernández, P.M.R. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25(1), 8–14.

- Nor, N. G. M., Bhuiyan, A. B., Said, J., & Alam, S. S. (2017). Innovation barriers and risks for food processing SMEs in Malaysia: A logistic regression analysis. Geografia-Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 12(2), 167-178.

- Pérez, P.J., & Marín, G.S. (2017). Does transitioning from family to non-family controlled firm influence internationalization? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(4), 775-792.

- Mousa, G.A.. & Hassan, N.T. (2015). Legitimacy theory and environmental practices: Short notes. International Journal of Business and Statistical Analysis, 2(1), 41–53.

- Milne, M.J., Tregidga, H., & Walton, S. (2009). Words not actions! The ideological role of sustainable development reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 22(8), 1211–1257.

- Ahmad, N.N.N., & Sulaiman, M. (2004). Environmental disclosures in Malaysian annual reports: A legitimacy theory perspective. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 14(1), 44–58.

- Nurhayati, R., Brown, A., & Tower, G. (2006). Understanding the level of natural environment disclosures by Indonesian listed companies. Journal of the Asia Pacific Centre for Environmental Accountability, 4-11.

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using the SPSS program, (4th Edition). Berkshire, England: Allen & Unwin.

- Pfau, M., Haigh, M.M., Sims, J., & Wigley, S. (2008). The influence of corporate social responsibility campaigns on public opinion. Corporate Reputation Review, 11(2), 145–154.

- Parsons, T. (1960). Structure and process in modern societies. New York: Free Press.

- Preston, L.E., & Post, J.E. (1975). Private management and public policy. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs.

- Rahim, A., Atan, R., & Kamaluddin, A. (2017). Human capital efficiency and firm performance: An empirical study on Malaysian technology industry. SHS Web of Conferences, 36(26), 1-11.

- Richardson, A.J. (1987). Accounting as a legitimating institution. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(4), 341–355.

- Rivas, J.L. (2012). Board versus TMT international experience: A study of their joint effects. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 19(4), 546-562.

- Salvioni, D.M., Gennari, F., & Bosetti, L. (2016). Sustainability and convergence: The future of corporate governance systems? Sustainability, 8(11), 1-25.

- Securities Commission Malaysia (SSM). (2012). Malaysian code of corporate governance 2012. Malaysia: Securities Commission Malaysia.

- Sepasi, S., Kazempour, M., & Mansourlakoraj, R. (2016). Ownership structure and disclosure quality: Case of Iran. Procedia Economics and Finance, 36, 108-112.

- Shanmugam, S. (2017). The relationship between corporate governance quality and sustainability reporting: An analysis of top performing companies and financially distressed companies. Unpublished dissertation, Auckland University of Technology Library.

- Slater, D.J., & Fowler, H.R.D. (2009). CEO international assignment experience and corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(3), 473-489.

- Suttipun, M. (2015). Sustainable development reporting: Evidence from Thailand. Asian Social Science, 11(13), 316-326.

- The 2007 Budget Speech (2006). The 2007 Budget Speech

- Vogt, M., Hein, N., da Rosa, F.S., & Degenhart, L. (2017). Relationship between determinant factors of disclosure of information on environmental impacts of Brazilian companies. Management Studies, 33(142), 24–38.

- Van Bardeleben, M. (2011). Implementing sustainability. European Coatings Journal, (11), 38–40.

- Weber, Y., & Schweiger, D.M. (1992). Top management culture conflict in mergers and acquisitions: A lesson from anthropology. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 3(4), 285-302.

- Yahya, W.K., & Ha, N.C. (2014). Investigating the relationship between corporate citizenship culture and organizational performance. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 19(1), 47–72.

- Yeoh, B.S.A. (2004). Cosmopolitanism and its exclusions in Singapore. Urban Studies, 41(12), 2431–2445.

- Young, R., & Jordan, E. (2008). Top management support: Mantra or necessity? International Journal of Project Management, 26(7), 713-725.

The focus of this study was to link the role of corporate governance on sustainability reporting disclosure for the top 100 public listed companies in Malaysia for the financial ending in 2016. The motivation of this study is to gauge whether companies comply with the recommendations provided in MCCG 2012 and follow the guidelines suggested in the Sustainability Reporting Guide 2015 (Bursa Malaysia, 2015). The study found that among the three (3) components of sustainability disclosure, the social theme had the most disclosure provisions, while the economic theme had the least disclosure provisions. In addition, this study showed that top management culture has a significant and positive influence on sustainability reporting disclosure. It implies that a positive culture brought in by the boards and prioritization of values-driven strategies can assist public listed companies to become more sustainable as shown in sustainability reporting. Top management commitment is a value laden behaviorally anchored cultural variable of the organizational environment (Dwivedi et al., 2014). This study also showed that the companies have become more aware that they should provide information to the public on their social activities to sustain their respective legitimacy. Hence, it was found that sustainability disclosure in public listed companies in Malaysia exhibited an encouraging degree of compliance that might indicate that they are in support of sustainability efforts in the future. However, currently only a small number of companies publish sustainability reporting. It is imperative that more incentives be offered so that more, if not all, will be motivated to publish their sustainability reporting.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Malaysian Accounting Research Institute (HICoE), Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, for providing the financial support needed for the project.