Research Article: 2024 Vol: 30 Issue: 1

The Influence of the Fear of Failure on the Entrepreneurial Behaviour of Chinese and United Kingdom Agricultural Students

Bozward, David, Global Banking School

Bell, Robin, University of Worcester

Carol Yongmei, Royal Agricultural University

Ma, Hongyu, Northwest A and F University

Fulin An, Northwest A and F University

Angba, Cynthia, Royal Agricultural University

Topolansky, Federico, Coventry University

Sabia, Luca, Coventry University

Rogers-Draycott, Matthew, Global Banking School

Hoyte, Cherisse, Coventry University

Citation Information: David, B., Robin, B., Yongmei, C., Hongyu M., An, F., Cynthia, A., Federico, T., Luca, S., Mathew, D.R., & Cherisse, H. (2024). The Influence of the Fear of Failure on the Entrepreneurial Behaviour of Chinese and United Kingdom Agricultural Students. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 30(1), 1-16.

Abstract

This paper determines whether fear of failure influences the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action for students who study agriculture at universities in the UK and China. It uses the international Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) data as the baseline which provides the ability to compare national and international data for entrepreneurial attitudes. The study looks at 679 students from both Chinese and UK Agricultural Universities. The total early-stage entrepreneurship activity rate for these students is higher than the national averages demonstrating that agricultural students are more entrepreneurial. For Chinese students’ opportunity identification has a significant positive affect on their entrepreneurial behaviour. However, this was not seen in the case of the UK students. In both cohorts, the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action was negatively mediated by fear of failure. The study contributes to the literature: firstly it challenges the core assumption that fear of failure is a premier obstruction to entrepreneurial action; secondly it provides a contextualised international study on the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity, fear of failure and entrepreneurial action. Thirdly, it calls for further contextualised education to experiential education to help develop the practice, behaviour and skills required to be entrepreneur.

Keywords

Fear of Failure, Agriculture, Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Behaviour, Entrepreneurial Action, Entrepreneurial opportunity

Introduction

Different environments shape different entrepreneurship dynamics determining the presence and the nature of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Acs, Desai, & Hessels 2008). The interplay between institutions and local development in turn affects other factors such as access to resources (Sabia, Bell & Bozward 2021) and ultimately contribute to form the national attitude to entrepreneurship as a form of collective orientation to business creation. This attitude presents itself as the ability to recognise new business opportunities and understand the competencies, knowledge, skills and experience to bring them to fruition thus in turn influencing the entrepreneurial activity across regions (Bosma & Schutjens 2011), ethnic groups (Levie 2007), subject cultures (Morris, Schindehutte & Allen 2005) and also across industrial sectors (De Massis et al. 2018). For example, rural and agricultural businesses differ from their urban counterparts in terms of a greater number of registered business ventures per head of population and a smaller size of businesses in terms of turnover and employment.

In the UK, farm diversification, which plays a critical strategy in the enduring viability of many farms with nearly two thirds (63%) saying that the income generated by diversification was ‘vital’ or ‘significant’ to their operations (DEFRA 2019, 2022), is often used as a metric to understand how entrepreneurial farmers behave with data showing that 65% of UK farmers have already diversified at least once their businesses. Therefore, we argue that an entrepreneurial attitude within the agriculture sector and more importantly in agricultural students is a pivotal factor in the long-term sustainability of farm-based ventures and the broader rural economy.

For many years, China has seen rural population moving to cities for economic benefits with Liu and Li (2017) reporting this figure to be 286 million people in 2017. However, the Chinese government's policy of ‘rural revitalization’ and the implementation of policies to support the rural population to set up and grow their own businesses has highlighted agricultural entrepreneurship as a key policy initiative (Ma et al. 2021).

In this study, we apply the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) survey (Reynolds, Hay & Camp 1999); (Reynolds, et al. 2005) which has been used in numerous nations around the world to provide a robust indicator of the available entrepreneurship policies and ecosystems. The fundamental approach of the GEM research is to survey individuals to develop an understanding of the attitudes and perceptions towards entrepreneurship and self-reported activity in starting a business. Since its inception, GEM has established itself as a dataset for internationally comparative entrepreneurship research (Bergmann et al. 2014) due to its unique longitudinal and national benchmarking capability. The last year in which both the UK and China participated was 2019 which saw 50 countries participating (Bosma et al. 2020).

Our work contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by empirically testing in what way fear of failure influences behaviour and also the challenges identified in current research findings. A series of researchers from Gartner in 1985 to (Audretsch, 2012) and Watson in 2013 to more recently (Welter et al. 2017) have all urged for more study that intentionally considers the entrepreneurial setting. This is further amplified by researchers who have identified that agricultural entrepreneurship requires further development (Carter 1999; McElwee 2006; Alsos , Carter, & Ljunggren 2011; Grande 2011; Brunjes and Revilla 2013; Fitz-Koch et al. 2018; Dias, Rodrigues, & Ferreira 2019).

The paper is structured as follows. The following section introduces the theoretical foundations of the study starting with presenting the research model and the concepts used within the hypothesis. The research method is presented with the analysis methods used. The results are then presented and discussed. The last section provides conclusions and opportunities for further research.

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

The fundamental premise of the paper is that fear of failure influences the bond between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action. To capture this relationship, we shall review each of these three theoretical areas in turn.

Concept of Entrepreneurial Intention

The intention to start a new business venture is derived from planned behaviour theory (Ajzen, 1991). When an individual has a developed entrepreneurial intention there is a higher likelihood they will start on a path of entrepreneurial behaviour or early-stage entrepreneurial activity (Bosma et al. 2012).

The theory of planned behaviour is the behaviour of individuals when influenced by their attitude. This was proposed by Ajzen in 1991 who described attitude as “the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation or appraisal of the behaviour in question” (p.188). Once people believe there are several business prospects available, they assess their personal five capitals (Yujuico 2008) to take advantage of such opportunities. Individuals will develop a favourable attitude toward the behaviour if they rate it positively (Ajzen 1991). This positive mindset will also lead to the establishment of intentions and behaviours. Similarly, we contend that a favourable perception of attractive business prospects will lead to entrepreneurial intent which has been supported by studies from Honjo (2015) and (Arafat & Saleem, 2017).

(Fayolle & Gailly, 2015) and (Tomy & Pardede, 2020) both applied the theory of planned behaviour to model the progress of entrepreneurial intention and the entrepreneurship education pedagogical processes and found that students who participated in entrepreneurship education programmes had a substantial and measurable bearing on their entrepreneurial intentions.

Ferreira et al. (2012) used psychological and behavioural characteristics within a cohort of students and found that self‐confidence, the need for achievement, and a personal attitude strongly affect entrepreneurial intention.

Nowiński and Haddoud, (2019) studied entrepreneurial intention within university students, building on studies which found that those exposed to entrepreneurship are more likely to perceive intentions as desirable (Krueger, 1993). In this study it was confirmed that role models can be used to predict intention and relate to studies based on agricultural families (Burton et al. 2005) (Pouratashi 2015) and (Ulvenblad et al., 2020) found that within agricultural students those who took entrepreneurship had higher levels of intention.

As intention has a strong relationship to behaviour, it follows that given their human capital and after participating in entrepreneurship education, that a person might be more likely to engage in entrepreneurship, in one way or another.

Concept of Entrepreneurial Opportunity

Sarason & Conger (2018) highlights that entrepreneurship research has focused on the nexus between the entrepreneur and their opportunities. The body of research on entrepreneurial opportunity has grown with numerous models having been presented in the last thirty years (Bhave 1994; Singh et al. 1999; De Koning 1999; Shane & Venkataraman 2000; Argichvili, Cardozo & Ray 2003; Sarasvathy, Dew, Velamuri & Venkataraman 2003; Ramoglou & Tsang 2016).

The diversity and range of models developed, are based on a broad range of management disciplines and are often conflicting but all fundamentally have perceived opportunity as the central motivating factor which encourages individuals to start their own businesses (McMullen & Shephered 2006). Logically we would expect recognition to precede the action of starting a business.

Randerson et al. (2016) and (Subbady & Bruton, 2015) have explored both the philosophical and the material nature of opportunities and highlighted the role that knowledge and experience play in informing their exploration. The ebb and flow of the entrepreneurial environment is shown as an interconnection between our personal, familial, and business dispositions, as expressed in our personal knowledge. As a result, opportunity recognition must be viewed as a skill that is not shared by all members of the community.

During this idea recognition/discovery, modelling and start-up phases of the entrepreneurial process (Bozward & Rogers-Draycott, 2017), the entrepreneur will start to deliberate and conceptualise new venture creation and make fundamental decisions regarding capitals to employ (Reynolds & White, 1997). Environmental factors are thought to affect the formation of new opportunities at the interface of individuals and teams during these phases. (Hindle 2010; Busenitz et al. 2014; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; George et al. 2016).

Busenitz et al. (2014) found that macro environmental factors influence the personal need for new opportunities to be found especially in periods of change or stability. Likewise, (George et al., 2016) confirmed that environmental factors create and moderate the relationships between the individual’s behaviour and their opportunity recognition.

Therefore, given the environmental and social factors which support agricultural students to act on opportunities, we begin by hypothesising the following:

H1: Perceived entrepreneurial opportunity has a positive effect on the entrepreneurial action of Chinese students.

H2: Perceived entrepreneurial opportunity has a positive effect on the entrepreneurial action of United Kingdom students.

Concept of Fear Of Failure

Researchers classified fear of failure (FoF) as a negative emotion that prevents people from beginning businesses (Li 2011; Patzelt & Shepherd 2011; Ekore & Okekeocha 2012; Wennberg, Pathak, & Autio 2013). Emotions have been shown to be adaptive responses that mirror assessments of particular events in the external world that are important for an individual’s well-being, according to the theory of appraisal of emotions. In this way, emotional experience is made up of the affect and perceptions of meanings that are connected in a single moment. As a result, an intentional condition is created in which the effect is perceived as being generated by a scenario. As a result, emotional experience arises from an assessment process and is linked to psychological and behavioural responses.

Experiencing FoF as a momentary emotional condition reduces a person’s willingness to start a business. FoF, according to Li (2011), is a feeling about the consequences of a new enterprise that influences people’s assessments of the value and likelihood of starting one. FoF, according to Caccoiti and Hayton (2015), is an obstruction to entrepreneurship and obstructs entrepreneurial behaviour.

Fear of failure, according to (Tsai, Chang, & Peng, 2016), is influenced by a person's perceived entrepreneurial abilities. Fear of failing is equated to the resistance to taking risks. As a result, the likelihood of encountering uncertain scenarios such as entrepreneurship is also reduced.

Fear of entrepreneurship failure has been shown to prevent individuals from entering the entrepreneurial process (Vaillant & Lafuente, 2007) due to the individual's risk adversity (Arenius & Minniti, 2005). It has also been demonstrated that in both factor-driven and efficiency-driven countries, entrepreneurs who are most afraid of failure also have the lowest intention rates (Bosma & Levie, 2010).

In previous work contrasting eastern and western perspectives on failure by (Begley & Tan, 2001) the researchers suggest that FoF, explored in the context of the perceived shame this might generate, can be a negative predictor of an interest in entrepreneurship. Although it should be noted that this conclusion is limited in scope, given the manner in which it is defined, and only partially supported.

More generally, there is research which finds that FoF is a deterrent to entrepreneurship (Shinnar et al., 2012; Noguera et al., 2013; Martin-Sanchez et al., 2018), that it is not (Bosma & Schutjens, 2011; Usman & Hussain, 2014), that the impacts are more nuanced (Damaraju et al., 2010); Primo and Green, 2011), and some which goes further, suggesting that it might even have a positive impact (Mitchell & Shepherd, 2011; Hayton et al., 2013).

Taken together, our work echoes that of (Lee et al., 2022) which suggests that the literature is, at best, inconclusive, more so regarding agriculture entrepreneurship, which receives almost no specific attention.

Given that our study focused on first year students and what will influence their behaviour, we would further hypotheses the following:

H3 Fear of failure plays a negative role in mediating the perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action of Chinese students.

H4 Fear of failure plays a negative role in mediating the perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action of United Kingdom students.

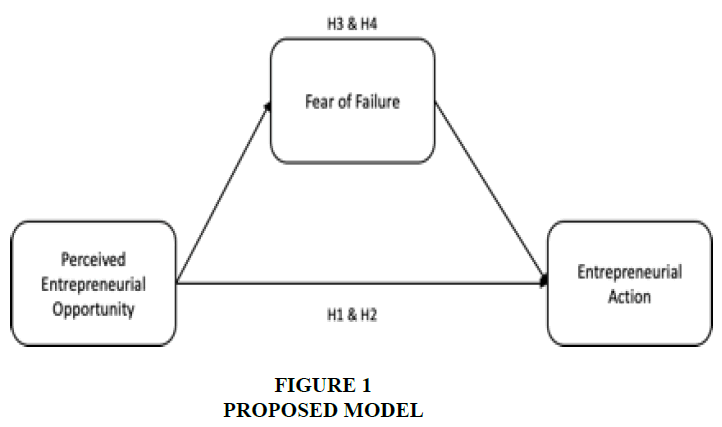

Research Model

The research model in Figure 1 summarises the hypotheses to be tested in order to determine (1) Can perceived entrepreneurial opportunity predict entrepreneurial action in Chinese and United Kingdom students?, (2) What influence does the fear of failure have on the relationship between the perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action of Chinese and United Kingdom students? and (3) Does fear of failure influence the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action differently in the Chinese and United Kingdom contexts?

Research Method

The English language GEM survey was translated into Chinese. The translated survey was then tested to ensure the questions were “functionally equivalent for the purposes of analysis” (Scheuch 1968: 113-4). This means that the responses to questions should represent the same concepts we want to measure across these multicultural and multinational groups. (Harkness et al., 2010).

The quantitative data was gathered from students through a self-administered anonymous paper-based GEM survey in the language of the tuition of that University, the first question 1, What University do you attend? (QU) determined their university and the following five questions, taken from the standard GEM survey (Reynolds et al., 2008) and related to this research: 2, What is your Age in years? (QA); 3, What is your Gender? (QG); 4, In the next six months will there be good opportunities for starting a business in the area where you live? (Q1); 5, Would fear of failure prevent you from starting a business? (Q2); and 6, Over the past twelve months have you done anything to help start a new business, such as looking for equipment or a location, organising a start-up team, working on a business plan, beginning to save money, or any other activity that would help launch a business? (Q3).

The research adopted categorical answers to measure perceived entrepreneurial opportunity, fear of failure, and entrepreneurial action to simplify the measures to improve comparability within the cross-cultural sample. Comparability and equivalence are the two biggest challenges within cross-cultural research (Sekaran, 1983), leading to the decision to reduce the range of answers to yes, no, or don’t know to create a more objective base for comparability and equivalence within the research. The desire to ensure that the questionnaire was simple for respondents to complete led to the decision to measure the constructs within the research through single items. Whilst, using multiple items to measure constructs is common, research has found that single item measures can be nearly as effective (e.g.; Hyland & Sodergren, 1996; McKenzie & Marks, 1999; Wanous et al., 1997). More succinct and concise measurement can save time, increasing the response rate and (Drolet & Morrison, 2001) concluded that as the number of synonymous items grows, respondents are more likely to engage in ‘mindless response behavior’, which might actually increase error.

The data was collected from four universities, three in China and one in the UK, all of which specialise in agricultural higher education. These were the Henan Agricultural University (HAU) which is based in Zhengzhou, Henan, China, the Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University (NAFU) which is based in Xianyang, the Shaanxi province, China, Shandong Agricultural University (SDAU) which is based in Shandong province, and the China and Royal Agricultural University (RAU) which is based in Gloucestershire, UK. The data was collected over three academic years, 2018, 2019 and 2020 before Covid-19 restriction took place.

For the research questions (Q1-Q3) the respondents were provided with the option to answer Yes, No, Don’t Know, or Refuse to Answer.

The survey was completed by 679 (Second year in China and First year in UK) Bachelors Undergraduate students, 201 from HAU, 162 from NAFU, 197 from SDAU and 119 from RAU. The average age of the students was 20.9 years old, with HUA with 19.9, NAFU with 21.4, SDAU with 20.2 and RAU with 20.9 average age of the students who completed the survey. All students except 2 were in the age range from 18-24. Across this student group, 62% of students were female, with HAU having 60%, NAFU having 51%, SDAU having 75% and RAU having 61% female student’s respondents.

Analysis and Results

The first question we shall address is (Q1), “In the next six months will there be good opportunities for starting a business in the area where you live?”. As these were mainly first year undergraduate students, the overall results of 48.8% of the respondents stating Don’t know should be expected. When we compare the Don’t know’s across the universities, we see HAU having 54%, NAFU having 47%, SDAU having 55% and RAU having 55%. Those stating No were 14%, 18%, 14% and 13%. For who stated Yes and see good opportunities in the next six months, the percentages are 25%, 35%, 30% and 31% respectively. This provides a consistent viewpoint from the student cohort.

The reported national perceived opportunity rate in the UK (GEM, 2019a) is reported to be 43.8%, in China (GEM, 2019b) it is 74.9%, and globally 53.6%. We can see that our Chinese respondents have a considerably lower perceived opportunity rate than their national counterparts (by around 45%), whilst the UK students have a 12.8% lower. This initial question provides a much lower rate of actions (29.9%) than the national averages (43.8% and 74.9%) and a very large (52.9%) who are not sure. This we can put down to this being a student population from the first year and their current mindset is focused on necessity or opportunity entrepreneurship.

The second question we shall address is (Q2) “Would fear of failure prevent you from starting a business?”. This provides 45% stating Yes, whilst 46% stating No and 6.9% stating they did not know. Given we have seen studies which have concluded either way, these findings that are similar are understandable. If we evaluate this on a university basis for Yes, we see HAU having 49%, NAFU having 48%, SDAU having 33% and RAU having 52%. The Chinese score from the three universities is 43%. The fear of failure rate in the UK (GEM, 2019a) is reported to be 44.5%, in China (GEM, 2019b) is 44.7% and globally 41.7%. From this we can see that agricultural students are broadly in line with national data provided. However, SDAU students have a lower rate of fear of failure with 33% and given 75% were female, this requires further analysis.

The third question we shall address is (Q3) “Over the past twelve months have you done anything to help start a new business, such as looking for equipment or a location, organising a start-up team, working on a business plan, beginning to save money, or any other activity that would help launch a business?”. This demonstrated that 14% students are actively launching a business. If we compare the university results, we see HAU having 13%, NAFU having 15%, SDAU having 14% and RAU having 13%, providing very similar rates across the student cohorts.

The total early-stage entrepreneurship activity rate in the UK (2019a) is reported to be 9.3%, in China (2019b) is 10.4% and globally 14.5%. We can see that agricultural students are more aligned with the global average than their national counterparts by having higher entrepreneurship activity.

The next stage was to compute a Spearman’s rho correlation on the variables under investigation (Q1, Q2 and Q3). This provided a correlation between the Q1 and Q3 of r = +0.177, p=0.002 showing a relationship between those that have started on the entrepreneurial activity and opportunities in the next six months.

Gender and (Q3) entrepreneurial activity also correlation r = +0.091, p=0.017 (Male = 1, Female =2) and (Yes =1 and No = 2), meaning that female students were marginally less likely to started an entrepreneurial activity. Gender and (Q2), fear of failure (Yes = 1, No =2) r = -0.096, p=0.013, showing that female students were marginally less likely to see fear of failure as a barrier to starting a business.

Logistic Regression

Logistic regression is a suitable econometric technique for predicting and explaining a binary categorical dependent variable (Menard, 2002). This paper researches the influence of Perceived Entrepreneurial Opportunity as an independent factor on a single non-metric (binary) dependent variable, which is Entrepreneurial Action. The mediator variable is Fear of Failure with the control variables being Age and Gender. The analysis will be presented for each hypothesis in turn and with this for Chinese and United Kingdom students. We will address each research question and associated hypothesis in turn below.

Research question one asked, Can perceived entrepreneurial opportunity predict entrepreneurial action in Chinese and United Kingdom students? A logistic regression was carried out to assess the effect of perceived entrepreneurial opportunity on the likelihood of entrepreneurial action in Chinese and UK students. The results, shown in Table 1, for all students shows that perceived entrepreneurial opportunity is significant when compared to the null model, (χ2 (1) = 10.033, p < 0.002), explained 4.8% of the variation of survival (Nagelkerke R2) and correctly predicted 77.8% of cases. The odds of those with a Perceived Entrepreneurial Opportunity (Q1) taking entrepreneurial action is 2.650 times higher than those who do not.

| Table 1 Entrepreneurial Opportunity Predict Entrepreneurial Action Logistic Regression | ||||||||

| Variables in the Equation | ||||||||

| Students | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | ||

| All | Step 1b | Q1 | 0.975 | 0.349 | 7.788 | 1 | 0.005 | 2.65 |

| Constant | -0.04 | 0.448 | 0.008 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.961 | ||

| H1 China | Step 1b | Q1 | 1.105 | 0.377 | 8.578 | 1 | 0.003 | 3.019 |

| Constant | -0.268 | 0.481 | 0.311 | 1 | 0.577 | 0.765 | ||

| H2 UK | Step 1b | Q1 | 0.77 | 0.822 | 0.877 | 1 | 0.349 | 2.159 |

| Constant | 0.712 | 1.022 | 0.486 | 1 | 0.486 | 2.038 | ||

| b. Variable(s) entered on step 1: Q1. | ||||||||

Considering H1: Perceived entrepreneurial opportunity has a positive effect on the entrepreneurial intention of Chinese students. This result shows that perceived entrepreneurial opportunity (Q1) is significant. The odds of Chinese students with a Perceived Entrepreneurial Opportunity (Q1) taking entrepreneurial action are 3.019 times higher than those who do not. The if we consider H2: Perceived entrepreneurial opportunity has a positive effect on the entrepreneurial intention of United Kingdom students, The result shows perceived entrepreneurial opportunity (Q1) is not significant.

Research question two asked, What influence does the fear of failure have on the relationship between the perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action of Chinese and United Kingdom students? Therefore, for the second test, a logistic regression was carried out to assess the effect of perceived entrepreneurial opportunity on the likelihood of entrepreneurial action when using Fear of Failure (Q2) as the mediation variable in three cases, All students, Chinese and UK students. The results in table 2, for all students is shown to not be significant.

| Table 2 Influence of Fear of Failure Logistic Regression | ||||||||

| Variables in the Equation | ||||||||

| Students | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | ||

| All | Step 1b | Q1 | 0.969 | 0.35 | 7.674 | 1 | 0.006 | 2.635 |

| Q2 | 0.085 | 0.288 | 0.088 | 1 | 0.766 | 1.089 | ||

| Constant | -0.163 | 0.61 | 0.071 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.85 | ||

| China | Step 1b | Q1 | 1.144 | 0.38 | 9.054 | 1 | 0.003 | 3.141 |

| Q2 | -0.118 | 0.313 | 0.143 | 1 | 0.705 | 0.888 | ||

| Constant | -0.154 | 0.649 | 0.056 | 1 | 0.812 | 0.857 | ||

| UK | Step 1b | Q1 | 0.8 | 0.842 | 0.902 | 1 | 0.342 | 2.225 |

| Q2 | 0.955 | 0.686 | 1.94 | 1 | 0.164 | 2.599 | ||

| Constant | -0.669 | 1.501 | 0.198 | 1 | 0.656 | 0.512 | ||

| b. Variable(s) entered on step 1: Q1, Q2. | ||||||||

The result shows in table 2 for all students, that fear of failure (Q2 = moderator) is not significant. Therefore, Fear of Failure has no influence on entrepreneurial action. The results also show for UK and Chinese students that fear of failure (Q2 = moderator) and perceived entrepreneurial opportunity (Q1) are not significant.

Research question three asked, Does fear of failure influence the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action differently in the Chinese and United Kingdom contexts?

In this regression the Mediation was Q2, (Fear of Failure) and controlled for gender. Result shows for All, China and UK students that perceived entrepreneurial opportunity (Q1), fear of failure (Q2 = moderator) and gender are not significant see table 3.

| Table 3 Influence of Fear of Failure on the Relationship Logistic Regression | ||||||||

| Variables in the Equation | ||||||||

| Students | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | ||

| All | Step 1b | Q1 | 0.927 | 0.353 | 6.907 | 1 | 0.009 | 2.528 |

| Q2 | 0.091 | 0.288 | 0.101 | 1 | 0.751 | 1.096 | ||

| Gender | 0.27 | 0.291 | 0.858 | 1 | 0.354 | 1.309 | ||

| Constant | -0.542 | 0.733 | 0.546 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.582 | ||

| H3 China | Step 1b | Q1 | 1.137 | 0.381 | 8.914 | 1 | 0.003 | 3.119 |

| Q2 | -0.117 | 0.313 | 0.138 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.89 | ||

| Gender | 0.258 | 0.298 | 0.745 | 1 | 0.388 | 1.294 | ||

| Constant | -0.546 | 0.79 | 0.477 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.579 | ||

| H4 UK | Step 1b | Q1 | 0.821 | 0.844 | 0.945 | 1 | 0.331 | 2.273 |

| Q2 | 1.009 | 0.692 | 2.124 | 1 | 0.145 | 2.742 | ||

| Gender | 0.617 | 0.694 | 0.791 | 1 | 0.374 | 1.853 | ||

| Constant | -1.654 | 1.858 | 0.793 | 1 | 0.373 | 0.191 | ||

| b. Variable(s) entered on step 1: Q1, Q2, Gender. | ||||||||

Therefore, we can dismiss both; H3 Fear of failure plays a negative role in mediating the perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action of Chinese students and H4 Fear of failure plays a negative role in mediating the perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action of UK students.

Discussion

In the case of the Chinese students, opportunity identification had a positive effect on entrepreneurial action. This offers some support for the contentions of (Honjo, 2015) and (Arafat & Saleem, 2017) that a favourable perception of attractive business prospects will lead to entrepreneurial intent and action. However, this was not the case in the UK cohort. This may suggest that UK students may not appreciate or identify opportunities in the same way to take advantage of the opportunities, are less inclined to act, unable to act, or perceived themselves as less able to act. The Chinese governments rural revitalisation policy has made agricultural entrepreneurship a key policy initiative. Whilst, Brexit may have produced uncertainty, which may have had a negative effect on taking advantage of opportunities. Pindado & Sánchez (2017) have shown that education negatively influences agricultural entrepreneurship. However, education can help agriculture students and graduates to not only identify entrepreneurial opportunities through the development of their entrepreneurial alertness which can help them in evaluating their environment but can also help them to develop an entrepreneurial mindset to take advantage of the opportunity and bring it to fruition (Rosairo & Potts, 2016). Entrepreneurial alertness is a significant factor in identifying entrepreneurial opportunities (Ardichvili, Cardozo & Ray, 2003) and is a characteristic of opportunistic entrepreneurs. An entrepreneurial mindset facilitates the individual in thinking and acting entrepreneurially and underlies successful strategies (Covin & Slevin, 2017). It is based on a range of abilities that include previous knowledge, pattern recognition skills and the ability to process information (Cui, Sun & Bell, 2021). Experiential education can play an important role in developing the required behaviours and skills that students need to successfully approach entrepreneurship practice (Ramsgaard & Christensen, 2018). These skills, behaviours and the appropriate knowledge can help agriculture students to move from the initial stage of identifying a possible opportunity to acting upon it.

The proposition that a fear of failure would have a significant mediating effect on the relationship between opportunity identification and entrepreneurial behaviour was rejected and not found to be the case in this research. A FoF has often been considered as a barrier to the successful conversion of intent into actual action. An appraisal of threat in taking an action triggers cognitive schemas around the results that failure will ensue (Conroy 2004). The resulting concerns over these outcomes can then lead to a fear of failure (Lazaras 1999). In this case, entrepreneurial intent into entrepreneurial action. Azjen’s (1991) Theory of planned behaviour proposed three motivational factors that influenced behaviour, namely, behavioural control, attitude to the behaviour, and the perception of societal norms. In the context of entrepreneurial intent these can be considered in terms of entrepreneurial effectiveness or efficacy, attractiveness of the idea, and perceived social norms (Fayolle & Liñán, 2014). The agricultural entrepreneur faces a great deal of uncertainty due to fluctuating agricultural community markets, changing climate as well family business dynamics which create a resistance to change (Naldi et al. 2007). Anything that impacts these factors (such as the fear of failure and its consequences) can impact (entrepreneurial) behaviour. Whilst some research suggests that the fear of failure did not impact the early stages of the entrepreneurial process, still others have concluded that the fear of failure acts as a deterrent to entrepreneurship (Martin-Sanchez, Contín-Pilart, & Larraza-Kintana, 2018); Koellinger, (Minniti, & Schade, 2013); (Noguera, Alvarez & Urbano, 2013); Shinnar, Giacomin & Janssen , 2012). In addition to the fears of financial failure (Ucbasaran et al. 2013), it has been argued that in collectivistic societies, such as those which are rural and/or agriculturally based, this fear of failure may be exacerbated by two cultural factors, the loss of face (Bedford, 2004), and familism, or the prioritisation of the family over one’s own aspiration (Schwartz et al. 2010). These might be expected to play a part, particularly in the Chinese context (Chua & Bedford, 2016). However, in this research, the data identified that in the Chinese cohort the fear of failure did not impact the relationship between opportunity and entrepreneurial behaviour. Similarly, the research identified that in the UK cohort the fear of failure did not impact the relationship between opportunity identification and entrepreneurial behaviour. Such findings conflict with other research (Shinnar, Giacomin & Janssen, 2012); (Noguera, Alvarez & Urbano, 2013); (Martin-Sanchez, Contín-Pilart & Larraza-Kintana 2018), including research where participants saw entrepreneurship as a risky undertaking (financial both to self and others, psychological, and career) that could end in failure and a waste of time, in a qualitative study of 40 final and penultimate year students in Singapore (Chua & Bedford, 2016).This may be due to the motivational factors being strong enough to override any potential fears of failure, or possibly be due to the cohorts consisting of students who may not be contemplating taking action in the near future and business failure, and its consequences, not being such an imminent reality.

Conclusion

The results indicated that agricultural Chinese students’ opportunity identification has a significant positive affect on their entrepreneurial behaviour. However, this was not seen in the case of the UK agricultural students. This may be because UK students may not appreciate or identify opportunities in the same way to take advantage of the opportunities, may be less inclined to act, or perceived by themselves as less able to do so, or may not be in a position to do so. Education can play an important part in helping students to move from opportunity identification to entrepreneurial behaviour. In particular, experiential education can help develop the practice, behaviour and skills required.

In both cohorts, the fear of failure played a negative role in mediating the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial opportunity and entrepreneurial action. This result is at odds with the bulk of research in this area although not with all.

Further research is required to understand these conflicting findings which may be contextual including the areas of research. In this case, the research was conducted in agricultural Universities in China and the UK. Further research could also seek to add further understanding by conducting interviews to gain a deeper insight into these findings and provide proposals for contextualised interventions.

Limitations of this research included the size and highly contextualised nature of the cohorts which could potentially constrain the generalisability of the findings. Future research can seek to confirm the findings across larger and more widely distributed areas. This research adopted binary assessments of opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial action, future research could utilise more nuanced measurements of opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial action, taking into account the different forms of action and opportunities that exist within entrepreneurship. Whilst a decision was taken to use categorical measures for the variables being researched in order to simplify the response options to support comparability and equivalence, this could be a limitation as it narrowed the options available to respondents. Additionally, the variables were measured using single items, which could potentially lead to lower content validity and reliability. Future research could build on this study by adopting continuous scales and multi-item measures.

References

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small business economics, 31, 219-234.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 50(2), 179-211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alsos, G. A., Carter, S., & Ljunggren, E. (Eds.). (2011). The handbook of research on entrepreneurship in agriculture and rural development. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Anwar ul Haq, M., Usman, M., Hussain, N., & Anjum, Z. U. Z. (2014). Entrepreneurial activity in China and Pakistan: A GEM data evidence. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 6(2), 179-193.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arafat, M. Y., & Saleem, I. (2017). Examining start-up Intention of Indians through cognitive approach: a study using GEM data. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 7, 1-11.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arafat, M. Y., Saleem, I., Dwivedi, A. K., & Khan, A. (2020). Determinants of agricultural entrepreneurship: a GEM data based study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16, 345-370.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business venturing, 18(1), 105-123.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Audretsch, D. (2012). Entrepreneurship research. Management decision, 50(5), 755-764.

Bedford, O. A. (2004). The individual experience of guilt and shame in Chinese culture. Culture & Psychology, 10(1), 29-52.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Begley, T. M., & Tan, W. L. (2001). The socio-cultural environment for entrepreneurship: A comparison between East Asian and Anglo-Saxon countries. Journal of international business studies, 32, 537-553.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bergmann, H., Mueller, S., & Schrettle, T. (2014). The use of global entrepreneurship monitor data in academic research: A critical inventory and future potentials. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 6(3), 242-276.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bhave, M. P. (1994). A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation. Journal of business venturing, 9(3), 223-242.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bosma, N. S. A. D. J., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Levie, J., and Tarnawa, A. (2020). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2019/2020 global report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School.

Bosma, N. S., & Levie, J. (2010). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2009 Executive Report.

Bosma, N., & Schutjens, V. (2011). Understanding regional variation in entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurial attitude in Europe. The Annals of regional science, 47, 711-742.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., Van Praag, M., & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of economic psychology, 33(2), 410-424.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bozward, D., & Rogers-Draycott, M. C. (2017). Developing a staged competency based approach to enterprise creation. Proceedings of the International Conference for Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development. ICEIRD.

Brünjes, J., & Diez, J. R. (2013). ‘Recession push’and ‘prosperity pull’entrepreneurship in a rural developing context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(3-4), 251-271.

Burton, R., Mansfield, L., Schwarz, G., Brown, K., & Convery, I. (2005). Social capital in hill farming. Report prepared for the International Centre for the Uplands by Macaulay Land Use Research Institute, Aberdeen & University of Central Lancaster, Penrith.

Busenitz, L. W., Plummer, L. A., Klotz, A. C., Shahzad, A., & Rhoads, K. (2014). Entrepreneurship research (1985–2009) and the emergence of opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(5), 1-20.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cacciotti, G., & Hayton, J. C. (2015). Fear and entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(2), 165-190.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carter, I. (1999). Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana. Education Research Paper. Report. DFID Education Publications Dispatch, PO Box 190, Sevenoaks, TN14 5SP, United Kingdom, England (Stock Number: ED31).

Chua, H. S., & Bedford, O. (2016). A qualitative exploration of fear of failure and entrepreneurial intent in Singapore. Journal of Career Development, 43(4), 319-334.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Conroy, D. E. (2004). The unique psychological meanings of multidimensional fears of failing. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26(3), 484-491.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (2017). The entrepreneurial imperatives of strategic leadership. Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset, 307-327.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100296.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Damaraju, Naga Lakshmi, Jay Barney, and Gregory Dess. "Stigma and entrepreneurial risk taking." Summer Conference, Imperial College London Business School. 2010.

de Koning, A. J. (1999). Conceptualising opportunity formation as a socio-cognitive process. INSEAD (France and Singapore).

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Majocchi, A., & Piscitello, L. (2018). Family firms in the global economy: Toward a deeper understanding of internationalization determinants, processes, and outcomes. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 3-21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Defra. (2019). The future farming and environment evidence compendium.

Dias, C. S., Rodrigues, R. G., & Ferreira, J. J. (2019). What's new in the research on agricultural entrepreneurship?. Journal of rural studies, 65, 99-115.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Drolet, A. L., & Morrison, D. G. (2001). Do we really need multiple-item measures in service research?. Journal of service research, 3(3), 196-204.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ekore, J. O., & Okekeocha, O. C. (2012). Fear of entrepreneurship among university graduates: a psychological analysis. International Journal of Management, 29(2), 515.

Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of small business management, 53(1), 75-93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of business research, 67(5), 663-666.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ferreira, J. J., Raposo, M. L., Gouveia Rodrigues, R., Dinis, A., & Do Paco, A. (2012). A model of entrepreneurial intention: An application of the psychological and behavioral approaches. Journal of small business and enterprise development, 19(3), 424-440.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fitz-Koch, S., Nordqvist, M., Carter, S., & Hunter, E. (2018). Entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector: A literature review and future research opportunities. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 42(1), 129-166.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of management review, 10(4), 696-706.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

GEM, 2019a UK, Retrieved February 1, 2020, from https://www.gemconsortium.org/economy-profiles/united-kingdom-2

GEM, 2019b China, Retrieved February 1, 2020, from https://www.gemconsortium.org/economy-profiles/china-2

Grande, J., Madsen, E. L., & Borch, O. J. (2011). The relationship between resources, entrepreneurial orientation and performance in farm-based ventures. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23(3-4), 89-111.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harkness, J. A., Braun, M., Edwards, B., Johnson, T. P., Lyberg, L., Mohler, P. P., & Smith, T. W. (2010). Comparative survey methodology. Survey methods in multinational, multiregional, and multicultural contexts, 1-16.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hayton, J., Cacciotti, G., Giazitzoglu, A., Mitchell, J. R., & Ainge, C. (2013). Understanding fear of failure in entrepreneurship: A cognitive process framework (No. 0003).

Hindle, K. (2010). How community context affects entrepreneurial process: A diagnostic framework. Entrepreneurship and regional development, 22(7-8), 599-647.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Honjo, Y. (2015). Why are entrepreneurship levels so low in Japan?. Japan and the World Economy, 36, 88-101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hyland, M. E., & Sodergren, S. C. (1996). Development of a new type of global quality of life scale, and comparison of performance and preference for 12 global scales. Quality of Life Research, 5, 469-480.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Koellinger, P., Minniti, M., & Schade, C. (2013). Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxford bulletin of economics and statistics, 75(2), 213-234.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 18(1), 5-21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, C. K., Wiklund, J., Amezcua, A., Bae, T. J., & Palubinskas, A. (2022). Business failure and institutions in entrepreneurship: a systematic review and research agenda. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 1997-2023.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Levie, J. (2007). Immigration, in-migration, ethnicity and entrepreneurship in the United Kingdom. Small Business Economics, 28, 143-169.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, Y. (2011). Emotions and new venture judgment in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28, 277-298.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International entrepreneurship and management journal, 11, 907-933.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liu, Y., & Li, Y. (2017). Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature, 548(7667), 275-277.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ma, H., Zhang, Y. C., Butler, A., Guo, P., & Bozward, D. (2022). Entrepreneurial performance of new-generation rural migrant entrepreneurs in China. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 28(2), 412-440.

Martin-Sanchez, V., Contín-Pilart, I., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2018). The influence of entrepreneurs’ social referents on start-up size. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14, 173-194.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mary George, N., Parida, V., Lahti, T., & Wincent, J. (2016). A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: insights on influencing factors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12, 309-350.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McElwee, G. (2006). Farmers as entrepreneurs: developing competitive skills. Journal of developmental entrepreneurship, 11(03), 187-206.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McKenzie, N., & Marks, I. (1999). Quick rating of depressed mood in patients with anxiety disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 174(3), 266-269.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management review, 31(1), 132-152.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Menard, S. (2002). Applied logistic regression analysis (No. 106). Sage.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mitchell, J. R., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Afraid of opportunity: The effects of fear of failure on entrepreneurial action. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 31(6), 1

Morris, M., Schindehutte, M., & Allen, J. (2005). The entrepreneur's business model: toward a unified perspective. Journal of business research, 58(6), 726-735.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjöberg, K., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Family business review, 20(1), 33-47.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Noguera, M., Alvarez, C., & Urbano, D. (2013). Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9, 183-197.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Negative emotions of an entrepreneurial career: Self-employment and regulatory coping behaviors. Journal of Business venturing, 26(2), 226-238.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pindado, E., & Sánchez, M. (2017). Researching the entrepreneurial behaviour of new and existing ventures in European agriculture. Small Business Economics, 49, 421-444.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pouratashi, M. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions of agricultural students: levels and determinants. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 21(5), 467-477.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Primo, D. M., & Green, W. S. (2011). Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 1(2), 20122006.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ramoglou, S., & Tsang, E. W. (2016). A realist perspective of entrepreneurship: Opportunities as propensities. Academy of management review, 41(3), 410-434.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ramsgaard, M. B., & Christensen, M. E. (2018). Interplay of entrepreneurial learning forms: a case study of experiential learning settings. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(1), 55-64.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Randerson, K., Degeorge, J. M., & Fayolle, A. (2016). Entrepreneurial opportunities: how do cognitive styles and logics of action fit in?. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 27(1), 19-39.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reynolds, P. D., & White, S. B. (1997). The entrepreneurial process: Economic growth, men, women, and minorities.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reynolds, P. D., Autio, E., & Hechavarria, D. M. (2008). Global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM): Expert questionnaire data. Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Reynolds, P. D., Hay, M., & Camp, S. M. (1999). Global entrepreneurship monitor. Kansas City, Missouri: Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership.

Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I., & Chin, N. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small business economics, 24, 205-231.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosairo, H. R., & Potts, D. J. (2016). A study on entrepreneurial attitudes of upcountry vegetable farmers in Sri Lanka. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 6(1), 39-58.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sabia, L., Bell, R., & Bozward, D. (2021). Crowdfunding and entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans. Entrepreneurial Finance, Innovation and Development: A Research Companion.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sarason, Y., & Conger, M. (2018). Ontologies and epistemologies in'knowing'the nexus in entrepreneurship: burning rice hay and tracking elephants. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 34(4), 460-479.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sarasvathy, S. D., Dew, N., Velamuri, S. R., & Venkataraman, S. (2010). Three views of entrepreneurial opportunity (pp. 77-96). Springer New York.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Scheuch, E. K. (1968). CHAPTER XII. The cross-cultural use of sample surveys: problems of comparability. Comparative research across cultures and nations, 176-209.

Schwartz, S. J., Weisskirch, R. S., Hurley, E. A., Zamboanga, B. L., Park, I. J., Kim, S. Y., & Greene, A. D. (2010). Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather?. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 548.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sekaran, U. (1983). Methodological and theoretical issues and advancements in cross-cultural research. Journal of international business studies, 14, 61-73.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of management review, 25(1), 217-226.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shinnar, R. S., Giacomin, O., & Janssen, F. (2012). Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions: The role of gender and culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and practice, 36(3), 465-493.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, R. P., Hills, G. E., Lumpkin, G. T., & Hybels, R. C. (1999, August). The entrepreneurial opportunity recognition process: Examining the role of self-perceived alertness and social networks. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 1999, No. 1, pp. G1-G6). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Suddaby, R., Bruton, G. D., & Si, S. X. (2015). Entrepreneurship through a qualitative lens: Insights on the construction and/or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunity. Journal of Business venturing, 30(1), 1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tomy, S., & Pardede, E. (2020). An entrepreneurial intention model focussing on higher education. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(7), 1423-144.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tsai, K. H., Chang, H. C., & Peng, C. Y. (2016). Refining the linkage between perceived capability and entrepreneurial intention: Roles of perceived opportunity, fear of failure, and gender. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(4), 1127-1145.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ucbasaran, D., Shepherd, D. A., Lockett, A., & Lyon, S. J. (2013). Life after business failure: The process and consequences of business failure for entrepreneurs. Journal of management, 39(1), 163-202.

Ulvenblad, P., Barth, H., Ulvenblad, P. O., Ståhl, J., & Björklund, J. C. (2020). Overcoming barriers in agri-business development: Two education programs for entrepreneurs in the Swedish agricultural sector. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 26(5), 443-464.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vaillant, Y., & Lafuente, E. (2007). Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity?. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(4), 313-337.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: how good are single-item measures?. Journal of applied Psychology, 82(2), 247.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Watson, T. J. (2013). Entrepreneurial action and the Euro-American social science tradition: pragmatism, realism and looking beyond ‘the entrepreneur’. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(1-2), 16-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Welter, F., Baker, T., Audretsch, D. B., & Gartner, W. B. (2017). Everyday entrepreneurship—a call for entrepreneurship research to embrace entrepreneurial diversity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(3), 311-321.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wennberg, K., Pathak, S., & Autio, E. (2013). How culture moulds the effects of self-efficacy and fear of failure on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(9-10), 756-780.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yujuico, E. (2008). Connecting the dots in social entrepreneurship through the capabilities approach. Socio-economic review, 6(3), 493-513.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 26-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23-14214; Editor assigned: 30-Oct-2023, PreQC No. AEJ-23- 14214(PQ); Reviewed: 13-Nov-2023, QC No. AEJ-23-14214; Revised: 18-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23- 14214(R); Published: 24-Nov-2023