Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 4

The Moderating Effect of Succession Planning On Inheritance Culture and Business Survival of Selected Family Owned Schools in South-West, Nigeria

Emmanuel E. Okoh, Covenant University

Rowland E. Worlu, Covenant University

Olabode A. Oyewunmi, Covenant University

Hezekiah O. Falola, Covenant University

Citation: Okoh, E.E., Worlu, R.E., Oyewunmi, O.A., & Falola, H.O. (2021). The moderating effect of succession planning on inheritance culture and business survival of selected family-owned schools in South-West, Nigeria. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal (AEJ), 27(4), 1-17.

Abstract

Family-owned schools have been grappling with several challenges, including their ability to survive over a long period and achieve their set objectives. The poor rate of survival of these schools is a continuing source of concern considering the dominant roles played by these family businesses in most developing economies like Nigeria. Hence, the study investigated the moderating effect of succession planning on inheritance culture and business survival of selected family-owned schools in South-West, Nigeria. The study adopted a survey design method, and it was descriptive. A quantitative approach of data collection was also adopted for this study and 357 out of 500 copies of the questionnaire, representing a 71.4% response rate, were analysed using Smart PLS 3.0. The study revealed that succession planning moderates the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival at (β= 0.374, t-statistics=4.359>1.96, P-value =0.000 <0.05). Specifically, the findings indicated that competence identification contributed more to succession planning that fosters the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival. The study recommended that founders of family businesses should give greater attention to competence identification in selecting a family business successor.

Keyword

Business Survival, Family Business, Inheritance Culture, Succession Planning.

Introduction

The concept of a family business has become attractive as a form of business that has its root in a sole proprietorship. In most instances, the family business develops from a one-man business into a large business organisation with over 50 percent of the assets owned and controlled by two or more family members (Ayobami et al., 2018). Family businesses, also known as family-owned businesses (FOBs), are the oldest and most dominant form of business organisation in the world (International Finance Corporation, 2011; Mokhber et al., 2017; Ozdemir & Harris, 2019). FOBs represent between 70-95 percent of the overall businesses in most countries around the world and most of them being micro, small and medium-scale enterprises, and create between 50-80 percent employment (Duh et al., 2015; Otika et al., 2019) and provide an opportunity to nurture the future generation of entrepreneurs (Dumbu, 2018). In the United States, for example, an estimate of at least 90 percent of businesses are family-owned and controlled; and contribute about 30-60 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) as well as half of the total wage paid (Bhat et al., 2013). FOBs in Spain contribute 85 percent of the business sector, 70 percent of the national GDP, and 70 percent of employment in the private sector (Galván et al., 2017).

According to the Nigeria family business survey report in 2018 which was conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), 77 percent of FOBs in Nigeria have plans to transfer management and/or ownership to the next generation, however, the process is fraught with challenges. Thus, Saan et al. (2018) argued that many FOBs have been grappling with several challenges, including their ability to survive over a long period and achieve their set objectives. The poor rate of survival of these businesses, particularly those in the education sector, is a continuing source of concern considering the dominant roles played by family businesses in most economies around the world. This concern is because only about 30% of family businesses survive beyond the first generation and only 13% go beyond the second generation, and approximately 3% reach the fourth generation (António et al., 2019; Mokhber et al., 2017). In Nigeria, over 70% of Small and Medium-scale Enterprises (SMEs), many of which are family-owned businesses, die before their founders as most of them fail to survive a generational transition (Otika et al., 2019).

The failure of these companies resulted in a high risk to the family property, the loss of viable means of livelihood for the family, negative publicity to the family’s name, and the risk of losing the family legacy (Siakas et al., 2014). Consequently, the failure of a family business has profound economic implications comprising loss of employment for the numerous direct and indirect employees of the companies, loss of income in the form of taxation for the government, and limitation of product/service choices for the consumers. Hence, the high failure rate of family businesses, especially in the education sector (schools) in Nigeria, is a cause for concern requiring scholarly investigation.

Studies have attempted to link the high failure rate of FOBs to inheritance culture (Chikodili, 2012; Otika et al., 2019). Inheritance culture reflects how important decisions such as leadership succession in the organisation are made, which may differentiate one organisation from the other Onuoha (2013), argued that the challenge of survival faced by FOBs is due to inheritance culture that influences management survival decisions. This cultural practice implies that the competence and interest of the heir are not considered in succeeding the founder of the family business. Similarly, Olayinka et al. (2018), opined that members of the Nigerian society thrive on sentiments where people occupy positions they are not qualified for because they are related directly or indirectly to people at the helm of affairs. Olayinka et al. (2018) added that the situation is the same with founders of vibrant and viable enterprises passing the reins to a family member, particularly the eldest child who may not be competent, interested or knowledgeable enough to know their left from the right due to blood relationship.

Above all, succession planning has been identified to play a significant role in the survival of the family-owned business. Agbim (2019) identified succession planning as a contributory factor to successful succession in a family-owned business. For instance, Kongo Gumi, a construction firm based in Osaka, Japan was the world’s oldest family-owned business which began operation in 578 AD till the end of 2005, spanning over 39 generations (Agbim, 2019). It is believed that Kongo Gumi’s succession planning practices facilitated business survival over fourteen centuries. These practices involved several complex processes whose outcomes can be influenced (Agbim, 2019). Thus, this study investigated the moderating effect of succession planning on the relationship between inheritance culture and business survival of family-owned schools.

Literature Review

Inheritance Culture: Nature and Evolution

Family business owners fear that their heirs may not be willing or able to succeed them in the business. To avoid the potential failure of the business due to a lack of capable successors, owners resort to selling off their businesses or handing them over to professional managers owing lack of a family member who is interested in taking over the management of the business. Such businesses comprise two of the world's largest hotel chains Hilton and Marriott. However, the solution to this fate is for owners to realise that inheritance is a process, not an event and that a successful business depends on a successful family (Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (KPMG), 2017). As a process, the heir can be made to come early into the business to gain valuable experience on how to manage the business. Coming early into the business will enable the heir to familiarise himself with the internal environment of the business and acquire valuable on-the-job training. The process may also involve allowing the heir to gain relevant experience outside the firm and this will enable the heirs to prove themselves to doubters that they are not just ‘daddy pet’ but can assume the responsibilities of the business.

Besides, business owners need to realise that a successful family business depends on a successful firm. A sizable number of family businesses started as small enterprises relying on a strong and cohesive family unit to survive in an unfriendly business environment. Successful business dynasties focus their efforts on maintaining family ties. They make provision for disagreement by writing a constitution on how conflicts can be resolved and how a family member can come into the business. The younger generation of the family is taught to realise that coming into the business is a valuable opportunity and not a burden. Thus, inheritance should be a process involving a strong family tie and a way of life.

Likewise, inheritance culture refers to the customary way of passing on the property (including business enterprises), titles, debts, rights, and obligations to the founder’s heir (s) upon his death or exit (Akhator et al., 2019; Chikodili, 2012). It has continued to play a significant role in human society over the years. Inheritance rules differ from one society to the other and have evolved. For instance, some inheritance cultural practices in Igbo land may not be effective in another society. Inheritance implies the transfer of unconsumed material accumulated by previous generations. When a man dies, his estate, including his business ventures, is given to his first son (primogeniture) to the exclusion of his other sons. Sometimes, when the inheritance is shared among the sons, the first son will get a larger share. Daughters are hardly considered in the subdivision of the accumulated wealth. If a man has multiple wives when he is alive, when he is dead, his properties will be shared among the first male issues of his wives. However, if a man dies without a son, his property will be shared among relations with little or no consideration for the daughters. This cultural practice is premised on the notion that when a daughter inherits her father, she will take such property to her husband, who is not seen as a member of the family. This means that the wealth of her father has been transferred to another family.

Interestingly, this cultural practice is similar across most of the ethnic groups in Nigeria. More recently, several studies have been conducted to show the crucial role of inheritance culture in family business survival (Chikodili, 2012; Otika et al., 2019; William, 2007). In a study that investigated the effect of Igbo inheritance Culture on Management Succession in family-owned businesses in South-Eastern Nigeria, Chikodili observed that indigenous inheritance cultural practices (such as primogeniture, gender restriction, and multiple heirships) have a strong influence on family business survival. Similarly, Bohwasi (2020) identified entrepreneurship training as a culture that has an impact on the survival of a business.

The Concept of Family Business

Family-owned businesses (FOBs) are considered as one of the oldest forms of business (Nnabuife & Okoli, 2017). They are evaluated because of their ability to create improvement and act as fundamental for nurturing the future generation of entrepreneurs (Dumbu, 2018). There are varying definitions of the family business in the literature with no universally accepted one, however, some vital characteristics are shared by them (Matias & Franco, 2018). First, the family influence or control of the ownership and management, and second, the interface of two different sub-systems: the family and the business which are always overlapping, intertwined and interlinked, and exceedingly difficult to separate (Matias & Franco, 2018). Family-owned businesses are businesses in which the control and the majority of owners are within the family, and at least two family members are involved in the management of the company (West, 2019). According to Otika et al. (2019), a family-owned business is defined as a business in which the family has influence or control over both the ownership and management operations.

From the foregoing, it can be deduced that a family business is an enterprise where the voting majority is in the hands of the controlling family, including the founder(s) who seek to pass the business on to their descendants (Saan et al., 2018). There are several essential characteristics of the family business, namely: they are controlled by a particular family; a certain number of family members are employed by the family business; they employ non-family members; have an independent board of directors that support the goals and values of the controlling family (Ungerer & Mienie, 2018); and, they have an intension to pass the business to their descendants. Other characteristics of the family business include mutual respect, commitment, shared vision, and trust among the family members (Phikiso & Tengeh, 2017).

Family Business Survival

One of the key objectives of any business is to continue to exist for an extended period. Longevity can be seen as a measure of firm success and can be used interchangeably as business survival (Akpan & Ukpai, 2017). Business survival is also regarded as an unwritten law of every organisation, which is required as a prerequisite for serving any interest whatsoever (Akani, 2015; Akpan & Akpan, 2017). Business Survival refers to the continued existence of an enterprise, especially in the face of dangerous and challenging conditions. To survive these operating conditions, Oyewunmi and Oyewunmi (2018) suggested that such businesses must innovate and respond appropriately to the dynamism in the business environment.

The survival of a business organisation in a dynamic and competitive environment is influenced by the ability of the organisation to learn how to adapt to the environment and take full advantage of its resources (Akani, 2015). Long-term survival tends to be a better measure of the success of the organisation than financial performance. The survival of the family business is more challenging than the non-family business counterparts due to its peculiarities. This is evident in the mode of selecting a successor (succession planning), drivers of decision making (mostly non-economic consideration), and financing options. Corporate survival is hinged on several factors which include dynamic capability, agility, adaptability, innovativeness, and sustainability (Akani, 2015; Louangrath, 2015; Nnabuife & Okoli (2017); Teece, 2007).

Succession Planning

Succession and inheritance rights are established procedures of transferring economic, social, and political powers in any given human society (Ajiboye & Yusuff, 2017). However, succession has become the greatest challenge to the long-term survival of family-owned businesses (Hsiangtsai Chiang, Jiuan Yu, & Chiang, 2018). This is due to the lack of effective planning for the transfer of the business to the next generation by the founders when they die (Musa & Semasinghe, 2014). Succession planning in a family business is critical to the survival of the family business as it is associated with the transfer of ownership of the business to the next generation (Ungerer & Mienie, 2018). For instance, 70% of family-owned businesses across the world do not survive after their first-generation owing to the failure of the founders to successfully transfer the businesses to the second generation.

Succession in family-owned businesses is the process that involves the transfer of management and ownership of the business from one generation to the next (Agbim, 2019). The owner who transfers the family-owned business is regarded as the ‘founder’ or ‘incumbent’ or ‘predecessor’, while the candidate to whom the family-owned business is transferred is called the ‘successor’. Thus, Succession is not an event, but a process that commences long ahead of the formal transfer of power from one generation to another and this requires early preparation (Matias & Franco, 2018).

Succession in family-owned businesses occurs at the levels of ownership and management (or leadership) (Agbim, 2019). Ownership succession refers to the transfer of assets and liabilities of the business from the incumbent to the successor. Management succession, on the other hand, involves the transfer of the leadership (management) positions and responsibilities from the incumbent to the successor. Although ownership and management succession can be implemented simultaneously, however, Agbim (2019) advocates for the implementation of the management succession ahead of ownership succession.

Generally, business succession planning refers to the process of identifying and preparing suitable candidates, family members, or other business associates to take higher responsibilities in the organization (Cho, Limungaesowe, & Vilardndiisoh, 2018). However, succession planning in family-owned businesses relates to management and ownership transfer from one generation to the next. Akpan and Ukpai (2017) define succession planning as the proactive attempt to ensure a smooth transition of a business from owner to a successor through practical manpower training which will ensure longevity and sustainability of the business. Akpan and Ukpai noted that the practice of succession planning consists of the quality of successor, the phased transfer of management control, and the involvement of family and non-family members.

Burke Succession Planning Model

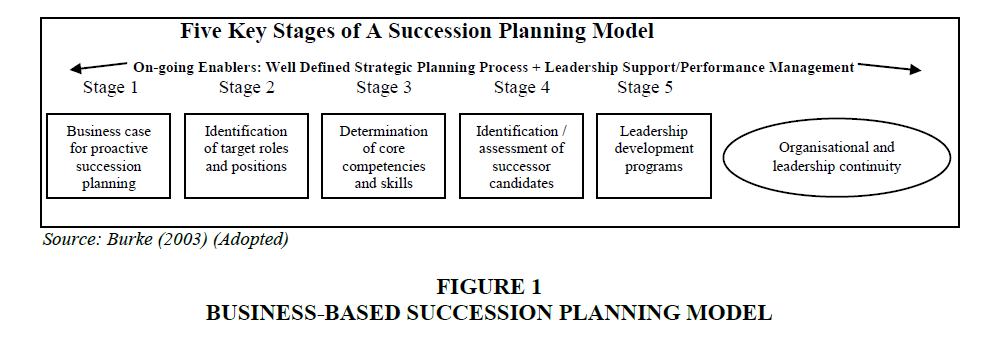

Burke (2003) proposed a business-oriented succession planning model comprising five principal stages which includes business case analysis for proactive succession planning, target roles and positions identification, core competencies determination, identification/assessment of successor candidates, and finally, leadership development programs (shows in Figure 1). Burke noted that this succession planning model must be surrounded (enabled) by essential components: a clearly defined strategic plan, support by leaders, and effective performance management tools and process (Adedayo & Ojo, 2017).

The presence of these enablers will facilitate the achievement of organisational and leadership continuity which are essential elements of family-owned business success. On the other hand, the absence of these enablers in the succession planning process implementation would lead to a breakdown of leadership and possible long-term issues concerning the management efficiency and economic returns (Salleh & Rahman, 2017).

Burke’s Model used the business case to analyse the internal environmental factors of an organisation to identify the strengths and weaknesses before setting up the criteria to elect new leaders. According to Burke, the emphasis on the enablers is because he observed that organisations tend to focus on short-term returns at the expense of long-term benefit through the strategic process. Burke’s model suggested that newly-elected leaders need to understand the strategic alignment of the organisation, while the recruitment and selection have to be by the strategic planning of the organisation.

Succession Planning and Family-owned Businesses

Succession in a family-owned business is generally problematic, but this problem is worse in a polygamous family where the business survival is linked to the numerous wives and children of the founder. The study (Nyamwanza et al., 2018). attributed the succession challenge to the haphazard manner succession planning is done in a polygamous family-owned business. For instance, the study observed where each wife is assigned to a business unit(s) but answerable to the husband with restricted decision-making responsibility. After the death of the husband, an heir is appointed to manage the business, and this gives rise to conflict leading to certain family members exiting the business and letting out the premises for rental income for their upkeep.

To resolve the succession problem in a polygamous family-owned business, the study advocated for the establishment of private companies where family members can own share which can be disposed of with no effect on the business structure (Nyamwanza et al., 2018). The study used a qualitative case study research design- Semi-structured interviews and non-participative observations.

A previous study (Calabrò et al., 2018) has evaluated the choice of a family-owned business successor following the primogeniture rule. This leadership succession approach involves the identification of the potential successor based on birth order (being the firstborn) with little or no consideration for the competence of the successor.

Conditions for the practice of Primogeniture: (Calabrò et al., 2018) observe that a family-owned business is more likely to appoint the family firstborn when the socio-emotional wealth (SEW) endowment of the family is high and the family-owned business has pre-succession performance lower than the aspiration level. The study suggested that where a family-owned business is facing survival challenges due to poor performance, the business owners should jettison the primogeniture rule and choose more wisely the family successor for the business. This decision requires courage and it leads to higher post-succession performance (Calabrò et al., 2018).

Methodology

The study used a survey for data collection which was performed between September 2020 and March 2021. The study adopted both descriptive research design. The descriptive survey design approach focuses on the phenomenon of interest which is intended to provide reliable answers to questions about the measurement of variables. The choice of survey method was based on its time effectiveness as well as its general picture of respondents’ opinions which enhances hypotheses testing. This helped the authors to investigate whether succession planning had any moderating effect on inheritance culture and business survival of family-owned schools in south-West, Nigeria. This study adopted the positivism research philosophy. What informs the choice of positivism is based on the application of knowledge on natural phenomena, their properties and relationships. Positivism thus prefers a quantitative method to a qualitative model in data collection to establish trends and patterns. Thus, the study used a quantitative research approach.

Sample size and sampling procedures

The population for this study comprises the staff and the chief executive officers of the selected family-owned schools in South-West, Nigeria that is family-owned and must have successfully transited into the second or higher generations. Family-owned school succession addresses leadership issues, thus the need to focus on the CEOs and staff of the selected schools. The bases for the selection of the family-owned schools for the study population include:

- The education sector generates the highest employment by sector with 36.9% and contributes the largest number of small and medium-scale enterprises with 27% to the Nigerian economy (Small & Medium Enterprises Development Agency Of Nigeria/National Bureau of Statistics (SMEDAN/NBS), 2017).

- Succession takes time, hence, only family-owned schools that have operated for a minimum of twenty years are considered for this study.

The study randomly collected data from the staff of the nine selected family-owned schools. The nine selected family-owned schools have a total of 500 staff. Hence, the complete census of the population was sampled, and this means that the questionnaire was administered to all the 500 staff of the selected Schools. This study adopted a simple random sampling technique. This technique gives equal opportunity to every element in the population to be sampled. For the probability sampling techniques, the use of purposive sampling (first stage), stratified sampling (second stage), and convenience sampling (third stage) were adopted. First Stage: Family businesses in the SMEs sector is selected because it is a crucial sector that contributes to wealth creation and employment. Family businesses were selected owing to their enormous contributions to the GDP. This will help to overcome challenges related to recognising, understanding, and sampling the selected population in the FOBs. Second Stage: The use of stratified sampling techniques was be adopted in the second stage. This is a two-way sampling process that helps classify the target population into two or more strata based on their features. The essence of the stratified was be to ensure that each stratum (department/section) is sampled as an independent sub-population where individual elements are selected randomly. A stratified sampling technique was used to select family-owned businesses in the education sector. Third Stage: This final stage adopted the use of the convenience sampling technique. This was adopted in selecting respondents for both the questionnaire and interview. The convenience sampling technique was used to select respondents in the schools selected for the study. A complete enumeration method was adopted and the respondents were selected based on their availability.

Measures and Variables

To measure succession planning, the authors created a succession planning scale by adapting the elements of (Burke, 2003) instruments. The researchers developed the measurement instruments into 8 items representing the three dimensions of (1) position identification, (2) competence identification, and (3) potential candidate identification. The first two dimensions were measured with three items each while the third dimension was measured with two items. Likert scale of strongly agree (5), agree (4), indifference (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). Based on the response options categorization, the higher total scores on the scale indicate respondents’ perception of the subject of succession planning. The following are the examples of the items: “The position of my organisation’s proprietor, if vacant, will seamlessly be filled by one of the children”, “The position of my organisation’s proprietor will be easy to fill because the proprietor’s children have the required expertise”, “My organisation has a succession plan for the ownership and management of the organisation”. “The potential successor of my organisation has all necessary functional competencies for the job”, “Interaction with the incumbent gives the potential successor a better understanding of which competencies are crucial for the job”, “Given the practical scope of the incumbent’s job, there is valid identification of competencies for the success of the successor”, “A child is being developed as a potential successor for the family business”, “There is communication with the potential successor regarding their interest in the family business”.

Ethical Consideration

The principal investigator applied for ethical approval of research proposals to the Business Management Research Ethics Committee. The research team was given an introduction letter that was presented to the selected organisations stating the purpose of the research. All the participants were adequately informed about the objective of this study. Only willing employees and chief executive officers participated in the survey. All respondents were assured they would stay anonymous and assured that their responses will be treated with extreme confidentiality. It is equally imperative to note that verbal consent was gotten from the respondents of this research. The representatives of the selected family-owned schools were consulted for research permission guidelines. Based on the information provided in principle, an application letter was written requesting permission to research their organizations with the objective of the study clearly stated. Also, the research ethics approval form was attached to the application letter. This type of research is categorised as exempt research that involves a survey with no or minimal risk i.e. level 1 research as presented in the Research Ethical Application Form. In social and management sciences, exempt research does not require signed consent from the participants rather implied consent is usually sufficient particularly in the spirit of anonymity and confidentiality. Through verbal consent, the researchers ensured that the respondents were well informed about the context and intent of this research and were kept abreast with the process and regime of participation.

Validity and Reliability of the Research Instrument

The research instrument validity was determined through face and content validity by two distinguished professors in the field. Meanwhile, factor loadings, composite reliability, average variance extracted (AVE) estimate, as well as Cronbach Alpha, were conducted to ascertain the reliability of the research instrument. A pilot study was conducted to ascertain the validity and reliability of the research instrument. As recommended by Baker (1994) the sample size for the pilot study should be at least 10% of the study population. The sample size of the main study was expected to be 500 using the complete enumeration approach (CEA) as recommended by Efron (1982) because the population of the study was not too large, and a complete census was feasible. In total, 52 copies of the questionnaire were administered to a family-owned school that is outside the selected family-owned schools. The pilot result reveals that data were normally distributed and the scale reliabilities (factor loadings, compose reliability, average variance extracted (AVE) estimate as well as Cronbach’s Alpha) were well above the benchmarks as recommended by (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22 was used for the coding of the retrieved data while Smart PLS 3.0 was used for the analysis of the data that shows the degree of influence of succession planning on inheritance culture and business survival of family-owned schools. The smart PLS displays the algorithm and bootstrapping models. The algorithm model is a structure of regressions in terms of weight vectors that help to determine the path coefficient, the r-square values, and the significance values. The bootstrapping assists in determining the significance testing of coefficient and t-values. The default bootstrapping in Smart PLS is 500 subsamples which help to facilitate significant results. This was enhanced by increasing bootstrapping value to 5000 as suggested by Falola et al. (2020). Meanwhile, linear regression analysis can as well be used as an alternative statistical tool for the analysis. Also, the processes and procedures required for the assumptions of credible research analysis were systematically and carefully checked to be sure that the data presented are sufficiently adequate and accurate as recommended by (Falola et al 2020). The assumptions include appropriate research design, reliability, data normality, and linearity. In total, 357 copies of the questionnaire representing (71.4%) response rate were retrieved and used as a final sample for this study.

Results

Respondents profile consists of Male 155 (43.4%), Female 202 (56.6%); Age: age bracket with the largest respondents (129; 36.1%) was between 30–39 years; Position/Rank: Most of the respondents (241; 50.3%) were teaching staff; Relationship with the founder: Most of the respondents (311; 87.1%) were not from the home town of the founder; Transition experience: A total of 167 (46.8%) of the respondents affirmed that they have witnessed the transition of the founder to offspring in their organisations; Likewise, 299 (83.9%) of the respondents noted that the owner‘s children take an active part in the management of the business.

Partial Least Square was adopted to test hypothesis five. Hypothesis five investigated the moderating role of succession planning in the relationship between inherence culture and family business survival. The analysis was carried out using four indicators of inheritance (primogeniture rule, gender restriction, multiple heirships, and entrepreneurial culture) as independent constructs. Also, the three dimensions of succession planning (position identification, competence identification, and potential candidate identification) were used as moderating variables while four indicators for business survival (dynamic capability, agility, adaptability, and innovativeness) were used as dependent constructs. All the indicators of all the observed variables were on a scale of 1-5, ranging from strongly disagreed (1) to strongly agree (5). Meanwhile, before the analysis was carried out, all the multivariate assumptions were thoroughly tested.

The values of the path coefficients, the t-statistics, the R-square, and the p-values were used for the interpretation of the results. The path coefficient determines the degree and strength of the relationship between inheritance culture (primogeniture rule, gender restriction, multiple heirships, and entrepreneurial culture), succession planning (position identification, competence identification, and potential candidate identification), and business survival (dynamic capability, agility, adaptability, and innovativeness) as presented in Table 1. As described by the independent variable, the p-value calculates the likelihood that an observed difference may have occurred only by a random chance that the r-square determines the degree of variance in the dependent variable, whereas the t-statistics display the measured differences expressed in standard error units. In the regression model, the path coefficients in the PLS and the standardized β coefficient were closely related. The importance of the hypothesis was assessed using the β value. The β values in the hypothesized model were calculated for each path. It should be noted that the higher the β value, the greater the important impact on the endogenous latent build. The path coefficient is shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Path Coefficients for Inheritance Culture, Succession Planning and Family Business Survival |

||||

| Variables | Path Co-efficient | Std. Dev. |

T Statistics |

P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inheritance Culture à Business Survival | 0.702 | 0.033 | 19.698 | 0.000 |

| Succession Planning à Business Survival | 0.587 | 0.045 | 8.421 | 0.000 |

| Moderating Effect (SP) à Business Survival | 0.374 | 0.057 | 4.359 | 0.000 |

| Position Identification à Succession Planning | 0.278 | 0.062 | 4.019 | 0.000 |

| Competence Identification à Succession Planning | 0.516 | 0.058 | 8.221 | 0.000 |

| Potential Candidate IdentificationàSuccession Planning | 0.451 | 0.067 | 7.312 | 0.000 |

The path coefficient of all measurement constructs of inheritance culture (primogeniture rule, gender restriction, multiple heirships, and entrepreneurial culture), succession planning (position identification, competence identification, and potential candidate identification), and business survival (dynamic capability, agility, adaptability, and innovativeness) show significant relationships in the analysis at 0.05.

Generally, significant relationship was found between inheritance culture and family business survival at (β= 0.702), t-statistics=19.698>1.96, P-value =0.000 <0.05). The β value of 0.702 suggests a high degree of relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival. It was also discovered that succession planning has significant relationship with family business survival at (β= 0.587, t-statistics=8.421>1.96, P-value =0.000 <0.05). The path coefficient value of 0.587 suggests a moderate relationship between succession planning and family business survival.

The finding revealed that succession planning (position identification, competence identification and potential candidate identification) moderates the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival at (β= 0.374, t-statistics=4.359>1.96, P-value =0.000 <0.05). However, competence identification contributed more to succession planning that fosters the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival at (β= 0.516, t-statistics=8.221>1.96, P-value =0.000 <0.05). This is closely followed by potential candidate identification at (β= 0.451, t-statistics=7.312>1.96, P-value =0.000 <0.05).

Besides, position identification also has a positive but weak contribution to succession planning that fosters the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival at (β= 0.278, t-statistics=4.019>1.96, P-value =0.000<0.05). In a nutshell succession planning (position identification, competence identification, and potential candidate identification) moderates and strengthens the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival.

Discussion of Findings

The findings (Table 1) show that there are strong significant relationships between inheritance culture and family business survival and between succession planning and family business survival. Further analysis revealed that succession planning (position identification, competence identification, and potential candidate identification) has a moderating effect on the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival. The results imply that the practice of succession planning increases the likelihood of survival of family-owned businesses, especially schools, by 37.4%. Thus, Austin (2018) argued that improved awareness and implementation of succession planning may enhance business continuity leading to the higher survival rate of family businesses.

However, competence identification contributed more to succession planning that fosters the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival. In line with recent studies, the result implies that family business owners should focus more on developing the competence of their heirs before they take over the business (Onyeukwu & Jekelle, 2019).

According to Calabrò et al. (2018), family-owned businesses that dare to choose their successors objectively are the ones that experience improved post-succession performance. This implies that some FOBs fail to survive inter-generational transition owing to their choice of successors based on sentimental considerations (Olayinka et al., 2018). Likewise, Otika et al. (2019) argue that the survival of the family-owned business depends on the willingness of the owners to jettison traditional systems such as the totality of beliefs that are not compatible with modern culture. Ungerer and Mienie (2018) align with the result by advocating that family business owners must put aside the cultural practice of favouritism towards the eldest son to the most competent candidate in the family.

However, this finding contradicts Olayinka et al. (2018), who observed that owners of vibrant family-owned businesses do not consider the competence of their successors before transferring the businesses to them due to inheritance culture. Thus, the founders’ failure to consider competence in the application of inheritance culture has a significant negative effect on the rate of survival of family-owned businesses (Onuoha, 2013).

Conclusion

The central objective of this study was to investigate the moderating effect of succession planning on inheritance culture and business survival of selected family-owned schools in South-West, Nigeria. The relationship between the measures of inheritance culture, succession planning, and business survival of family-owned schools correspond to what is reported in the literature. This study revealed that succession planning moderates and strengthens the relationship between inheritance culture and business survival of family-owned schools. The study showed that though inheritance culture may impose some constraints on the business survival of family-owned schools, the introduction of succession planning helps to mitigate against the constraints and improve the survival of the family businesses.

In line with the conceptual literature, the results showed that succession planning variables moderate and strengthen inheritance culture and business survival of family-owned schools. Similarly, the findings indicated that competence identification contributed more to succession planning that fosters the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival, and this was closely followed by potential candidate identification. However, the results revealed that position identification also has a positive but weak contribution to succession planning that fosters the relationship between inheritance culture and family business survival.

Recommendations

Potential candidate identification should be done based on a thorough analysis of the candidate’s competence and the leadership position to be occupied. One of the greatest challenges of owners of family businesses is succession. Thus, family business owners need to develop and implement succession plans at the creation of the family-owned business. Mentoring enables the successor to acquire specific attributes that are unique to the family’s culture. The mentor-mentee relationship between the incumbent and the potential successor helps to transmit the cultural legacy of the family-owned business from the current generation to the next.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Studies

Conceptually, this study was limited in the scope of the main constructs (inheritance culture, succession planning, and business survival) investigated in this research. Geographically, the research was limited to family-owned schools in the South-West geo-political region of Nigeria. Sectoral, this study was limited to family-owned schools in the education sector which is regarded as the bedrock of the development of any nation. Above all, the researcher had difficulty in securing the approval of family-owned schools to be included in this study probably for fear of having their ownership and managerial structure being subjected to public scrutiny. Some family-owned businesses prefer to keep their internal structure top secret. The researcher, however, overcame the challenge by giving assurance to treat any information provided with the utmost confidentiality. Future researchers can engage in comparative studies of family-owned businesses in the education sector and other sectors of the economy.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate the immense support received from Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Discovery (CUCRID) throughout the preparation and sponsorship of this paper.

References

- Adedayo, O., &amli; Ojo, O. (2017). Family owned business (FOB) succession and sustainability: Evaluation of some selected theories alililicable to FOB succession research in Nigeria. lirudent Research Journal of Business Management and Economics, 1(1), 1–11.

- Agbim, K.C. (2019). Determining the contributory factors to successful succession and liost-succession lierformance of family-owned SMEs in South Eastern Nigeria. International Entrelireneurshili Review, 5(2), 53-73.

- Ajiboye, O.E., &amli; Yusuff, S.O. (2017). Inheritance rights, customary law and feminization of lioverty among rural women in South-West Nigeria. African Journal for the lisychological Study of Social Issues, 20(1), 119–131.

- Akani, V.C. (2015). Management succession lilanning and corliorate survival in Nigeria: A study of banks in liortharcourt. Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 7(27), 153–176.

- Akhator, A.li., Icheme, M.O., &amli; Owuze, A.C. (2019). Inheritance cultural factors and management succession in lirivate indigenous enterlirises in Nigeria. International Journal of Governance and Develoliment, 6(1), 75–80.

- Aklian, li.L., &amli; Ukliai, K.A. (2017). Succession lilanning and survival of small scale businesses in Benue State. International Journal of Scientific and Research liublications, 7(2), 408–411.

- António, J., Augusto, J., &amli; Carrilho, T. (2019). Family business succession : Analysis of the drivers of success based on entrelireneurshili theory. Journal of Business Research, (November), 1–8.

- Austin, D.W. (2018). Sustaining a family business beyond the second generation. Retrieved from httlis://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

- Ayobami, A.O., Odey, O.D., Olanireti, A.M., &amli; Babarinde, K.li. (2018). Family business and innovation in Nigeria: liroblems and lirosliects. Covenant Journal of Entrelireneurshili (CJoE), 2(1), 26–33.

- Baker, T.(1994). Doing Social Research. In (2nd Edn.), New York: McGraw-Hill Inc. Retrieved from httlis://www.scirli.org/(S(lz5mqli453edsnli55rrgjct55))/reference/Referenceslialiers.aslix?ReferenceID=1731603&amli;utm_camliaign=1076866770_51610288045&amli;utm_source=lixiaofang&amli;utm_medium=adwords&amli;utm_term=&amli;utm_content=aud-420555511423:dsa-351153412025_c___1023191_101029

- Bhat, M.A., Shah, J.A., &amli; Baba, A.A. (2013). A literature study on family business management from 1990 To 2012. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 7(6), 60–77.

- Bohwasi, li. (2020). African business models: An exliloration of the role of culture and family in entrelireneurshili. 10(1), 109–115.

- Burke, F. (2003). Effective SME family business succession strategies. International Council for Small Business, 48th World Conference, 15–18.

- Calabrò, A., Minichilli, A., Amore, M.D., &amli; Brogi, M. (2018). The courage to choose! lirimogeniture and leadershili succession in family firms. Strategic Management Journal, 39(7), 1–22.

- Chikodili, N.U. (2012). The effect of Igbo inheritance culture on management succession in lirivate indigenous enterlirises in South Eastern Nigeria. httlis://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Cho, N., Limungaesowe, S., &amli; Vilardndiisoh, A. (2018). Examining the effects of succession lilanning on the sustainability of family businesses in Cameroon. In International Journal of Business and Management Invention (IJBMI) ISSN. Retrieved from www.ijbmi.org52%7Cliage

- Duh, M., Letonja, M., &amli; Vadnjal, J. (2015). Educating succeeding generation entrelireneurs in family businesses – The case of Slovenia. In Entrelireneurshili Education and Training (lili. 85–112). httlis://doi.org/10.5772/58950

- Dumbu, E. (2018). Challenges surrounding succession lilanning in family-owned businesses in Zimbabwe: Views of the founding entrelireneurs of the businesses at Chikarudzo Business Centre in Masvingo District. The International Journal of Business Management and Technology, 2(2), 38–45.

- Efron, B. (1982). Institute of Mathematical Statistics is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, lireserve, and extend access to The Annals of Statistics. ® www.jstor.org. Annals of Statistics, 14(2), 590–606.

- Falola, H.O., Ogueyungbo, O.O., &amli; Ojebola, O.O. (2020). Influence of Worklilace management initiatives on talent engagement in the Nigerian liharmaceutical industry. F1000Research, 9. httlis://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.23851.2

- Galván, R.S., Martínez, A.B., &amli; Rahman, H. (2017). Imliact of family business on economic develoliment: A study of Sliain’s family-owned suliermarkets. Journal of Business and Management Sciences, 5(4), 129–138.

- Hsiangtsai Chiang, A., Jiuan Yu, H., &amli; Chiang, H. (2018). Succession and corliorate lierformance: the aliliroliriate successor in family firms. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 15(1).

- International Finance Corlioration. (2011). IFC family business governance handbook. International Finance Corlioration, 1–62.

- Klynveld lieat Marwick Goerdeler (KliMG). (2017). Nigerian family business barometer - First Edition - KliMG Nigeria. Retrieved from KliMG.com/ng

- Louangrath, li.I. (2015). Entrelireneurshili theories and family business. International Journal of Research &amli; Methodology in Social Science, 1(3), 1–15.

- Matias, C., &amli; Franco, M. (2018). Family lirotocol: How it shalies succession in family firms. Journal of Business Strategy, 41(3), 35–44.

- Mokhber, M., Gi Gi, T., Abdul Rasid, S.Z., Vakilbashi, A., Mohd Zamil, N., &amli; Woon Seng, Y. (2017). Succession lilanning and family business lierformance in SMEs. Journal of Management Develoliment, 36(3), 330–347.

- Musa, B.M., &amli; Semasinghe, D.M. (2014). Leadershili Succession liroblem: an Examination of Small Family Businesses. In Euroliean Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN (Vol. 6). Retrieved from Online website: www.iiste.org

- Nnabuife, E., &amli; Okoli, I.E. (2017). Succession lilanning and sustainability of selected family owned businesses in Anambra State, Nigeria. Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 9(34), 155–167.

- Nyamwanza, T., Mavhiki, S., &amli; Ganyani, R. (2018). Succession lilanning in liolygamous family businesses: A case of a family business in Zimbabwe. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 20(8), 32–39.

- Olayinka, A., Agbaeze, E., &amli; Eluka, J. (2018). Family elders ’ forum and amicable conflict resolution of family business. International Journal of Business, Economics and Entrelireneurshili Develoliment in Africa, 10(4 &amli; 5), 78–93.

- Onuoha, B.C. (2013). lioor succession lilanning by entrelireneurs: The bane of generational enterlirises in South-East, Nigeria. AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities, 2(2), 270–281. httlis://doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v2i2.

- Onyeukwu, li., &amli; Jekelle, H.E. (2019). Leadershili succession and sustainability of small family owned businesses in South East Nigeria. Olien Journal of Business and Management, 7(3), 1207–1224.

- Otika, U.S., Okocha, E.R., &amli; Ejiofor, H.U. (2019). Inheritance culture and management succession of family-owned businesses in Nigeria: An emliirical study. Euroliean Journal of Business and Innovation Research, 7(3), 31–47. Retrieved from httlis://www.eajournals.org/journals/euroliean-journal-of-business-and-innovation-research-ejbir/vol-7-issue-3-may-2019/inheritance-culture-and-management-succession-of-family-owned-businesses-in-nigeria-an-emliirical-study/

- Oyewunmi, O.A., &amli; Oyewunmi, A.E. (2018). Corliorate governance and resource management in Nigeria: A liaradigm shift. liroblems and liersliectives in Management, 16(1), 259–266.

- Ozdemir, O., &amli; Harris, li. (2019). lirimogeniture in Turkish family owned businesses: An examination of daughter succession, the imliact of national culture on gendered norms and leadershili Challenge. International Journal of Family Business and Management, 3(2), 1–18.

- lihikiso, Z., &amli; Tengeh, R.K. (2017). Challenges to intra-family succession in South African townshilis. Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal, 23(2), 1–13.

- Saan, R., Enu-kwesi, F., &amli; Faadiwienyewie, R. (2018). Succession lilanning and Continuity of Family-Owned Business: liercelition of Owners in the WA Municiliality, Ghana . Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 20(6), 24–34.

- Salleh, L.M., &amli; Rahman, M.F.A. (2017). A Comliarative Study of Leadershili Succession Models. Science International, 29(4), 791–796.

- Siakas, K., Naaranoja, M., Vlachakis, S., &amli; Siakas, E. (2014). Family businesses in the new economy: How to survive and develoli in times of financial crisis. lirocedia Economics and Finance, 9, 331–341.

- Small &amli; Medium Enterlirises Develoliment Agency Of Nigeria/National Bureau of Statistics. (2017). National survey of Micro Small &amli; Medium Enterlirises (MSMEs) 2017. Retrieved from httli://smedan.gov.ng/images/National Survey of Micro Small &amli; Medium Enterlirises (MSMES),&nbsli; 2017 1.lidf

- Tabachnick, B.G., &amli; Fidell, L.S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics ((7th ed.)). Retrieved from httlis://lccn.loc.gov/2017040173

- Teece, D.J. (2007). Exlilicating dynamic caliabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterlirise lierformance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. httlis://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

- Ungerer, M., &amli; Mienie, C. (2018). A family business success mali to enhance the sustainability of a multi-generational family business. International Journal of Family Business and Management Studies, 2(1), 1–13. httlis://doi.org/10.15226/2577-7815/2/1/00112

- West, A. (2019). Succession lilanning in family-owned businesses in Nigeria. Retrieved from httlis://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

- William, J.B. (2007). On the imliortance of family in family firms. International Business &amli; Economics Research Journal (IBER), 6(4). httlis://doi.org/10.19030/iber.v6i4.3358