Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

The Relationship Between Leadership - Members Exchange and Organizational Commitment in Saudi Arabia Healthcare Sector

Algathia Salem Ali, Taif University

Salem Ali, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Abdul Rashid Abdullah, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Rosmah Mohamed, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Yee Choy Leong, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Keywords

Leadership Members Exchange, Organisational Commitment, Self-Enhancement, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

The relationship between leadership - members exchange and organisational commitment has caught attention from human resource management and organisational behaviour scholars in recent years. According to recent management and psychological science literature, leadership is a term with several characteristics and a wide range of applications. This analysis aims to examine the impact of leadership - member exchange types on employee organisational commitment in Saudi Arabia's healthcare sector. This research focuses on the importance of self-enhancement as a mediating factor in the partnership between leadership - participant sharing and organisational engagement. This study employs a theoretically built model To observe and describe the interaction between variables. As a result, the leadership - members exchange theory and the Social Identity Theory is used in this analysis to address the relationship as mentioned earlier. Theoretical and observational experiments have been analysed and summarised in this paper to further investigate the connection. The thesis comes to a close with a drawback and a suggestion for potential studies.

Introduction

Organisations have no choice but to adapt over time when the world is changing at such a rapid pace (Van Knippenberg, Martin & Tyler, 2006). Typically, transition happens as a company moves from the current condition to a more favourable future state. To stay successful in today's business world, companies must constantly adapt (Iveroth & Hailencreutz, 2016; Stead & Stead, 2014). The shift can arise due to internal issues or new policies aimed at lowering costs and improving efficiency. Leadership has often been a critical part of achieving new organisational transformation at this time. Scholars also recommended that the position of leadership is important to an organisation's success. For maximum success, organisations need good leadership to develop a mission and encourage organisational participants to pursue the vision (Robbins & Judge, 2013). Employee dedication to their careers, work morale, and mission success is enhanced through leadership (Lussier & Achua, 2013). As a result, leadership practices are critical in achieving more empowered and active workers.

In the context of healthcare performance growth, leadership is a hot topic (Long & Javidi, 2016; Almgren, 2017), and quality and safety management remain a priority for healthcare provision (Taylor et al., 2014; Turner, 2017). "Leadership learning activities are described as instructional processes designed to enhance individuals' leadership skills," writes McAlearney (2006). The research on leadership has shown that leadership personality and efficiency are the most important factors in determining organisational effectiveness (Wang et al., 2011; Turner, 2017).

"Many countries across the world are struggling to improve healthcare quality, contain or control costs, and have access to healthcare for their citizens and much has been written about the United States and European struggles to balance quality, cost, and access to healthcare," wrote Walston, et al., (2008). This is in accordance with Carlström & Ekman (2012), which highlighted many crucial issues confronting the global healthcare system, including the high cost of treatment and the growing number of patients with long-term sicknesses (Carlström & Ekman, 2012). On the other hand, the new research literature has discovered that there is a clear correlation between leadership and management processes of healthcare organisations when it comes to patient loyalty and financial success, which includes overall standard of service and employee engagement (Turner, 2017).

In the same way, the present condition of the healthcare sector has posed obstacles to its leadership and administration activities due to a lack of municipal health professionals and a surge in demand for healthcare (Liu et al., 2017; Maurer, 2015). Access to healthcare infrastructure, the privatisation of public hospitals, and the implementation of policies such as e-health services, which necessitate the development of healthcare information systems, are all additional roadblocks (Alsulame et al., 2016). Other factors cited by Watson, et al., (2008) as presenting a challenge to the system's efficacy include a rise in the number of migrant staff and the presence of adolescents. These factors stymie the government's attempts to expand the sector and add to patient dissatisfaction with government policies.

On the other side, Saudi Arabia's healthcare system has a comprehensive development and modernisation plan in effect to increase productivity and offer better treatment (Albejaidi, 2010; Al Otaibi, 2017). Also, the Saudi government has prioritised healthcare (Albejaidi, 2010; Alkhamis, 2017). "The Ministry of Health will formulate the national strategy for healthcare facilities in partnership with other healthcare providers, and the Council of Health Services will oversee it," Almalki, et al., (2011) report. In 20 years, the policy is planned to be enforced (Almalki et al., 2011). Furthermore, the Ministry of Health (MOH) is attempting to implement a host of health-related programmes as part of the National Transformation Program (NTP) 2020 and Saudi Vision 2030. (The Ministry of Saudi Health, 2017).

Saudi Arabia announced "Vision 2030" in 2016. KSA is to be "the centre of the Arab and Islamic worlds, the investment powerhouse, and the hub linking three continents," according to the plan's vision. Furthermore, the government has identified 24 objectives to be met. Among the most noteworthy achievements are: raising the share of non-oil exports from 16 -50 %; increasing the private sector's contribution to GDP from 40 -65 %; ranking among the top ten countries on the Global Competitiveness Index; and increasing the GE index's effectiveness from 80- 20 %. The Saudi Vision 2030 aims to shift Saudi Arabia's economic dependency away from hydrocarbons and into private-sector investments in national and foreign issues such as healthcare. In 2030, this is expected to increase the allocation to GDP from 40-65 % (Rahman & Alsharqi, 2018).

For many years, the government of Saudi Arabia has had a policy aim of privatising health insurance as a means of reforming this critical market of health care facilities (Alkhamis, 2017). The state funds Saudi Arabia's healthcare financing. On the other hand, the Saudi administration has embarked on an ambitious transition agenda to revitalise the Kingdom's infrastructure and prepare it for future demographic and economic challenges. The National Transformation Plan is a policy that aims to boost economic efficiency, build employment, and raise Saudi national investment in the private sector. Privatising health care is one part of the reform agenda, which aims to collect funds for the nationwide scheme while also encouraging quality and improving patient support (Rahman & Alsharqi, 2018).

Despite the government's efforts, the healthcare system continues to face problems, including an ever-increasing number of patients, labour shortages, the evolving nature of diseases and illnesses, and access to healthcare services (Almalki, 2011). These difficulties also raised the government's workload and necessitated immediate intervention. To address this question, the government has sought to quantify the impact of these problems on the healthcare system. Researchers and physicians agree that privatising the healthcare system, i.e., public hospitals is the only solution. Steps have been taken to make this a fact, bypassing the government's policy decision. Consequently, most municipal hospitals will be sold in the coming years (Al-Hanawi et al., 2018).

The privatisation of the healthcare system necessitates extremely successful leadership strategies. Public and private management's leadership styles and behaviours vary (Aarum, 2016; Anderson, 2010; Hansen & Villadsen, 2010). Furthermore, Hooijberg & Choi (2001) found that the correlation between effectiveness and goal-oriented leadership is weaker in the public sector than in the private sector. This is because public-sector employees have less workplace control than private-sector managers. In addition, the public sector makes a little appeal to leadership, while the private sector emphasises leadership as a critical feature (Bedrule-Grigoruta, 2012). In the Saudi healthcare system, research is scarce in this region (Alharbi, 2018).

In the twenty-first century, leadership is critical to the success of every organisation (Mumford & Gibson, 2011), furthermore, leadership is critical in shaping workers' engagement and efficiency to provide high-quality services (Lee, 2011). In the healthcare sector in Saudi Arabia, it has been observed that there is a lack of good leadership positions and practises to improve organisational performance and accomplish organisational objectives (Al semari, 2015; Yaser, 2019). Orthodox bureaucracy, weak interactions with employees, and a lack of communication abilities are all critics of healthcare leadership models, according to Saati (2016). Furthermore, the Saudi healthcare sector is undergoing an organisational reform (privatisation), which could affect employees' loyalty to the business (Fernandez & Pitts 2007; Hechanova et al., 2018; Higgs & Rowland 2005, 2010; Van der Voet et al., 2016). Employees' organisational loyalty can be jeopardised due to this mechanism (Van der Voet et al., 2016), as it entails a potentially threatening shift of commitment (Hechanova et al., 2018). It is challenging to maintain organisational loyalty through transitions, including pre-change levels of commitment. Owing to the employees' near alignment with the organisation's priorities, organisational reform has a detrimental impact on organisational engagement, which can cause employees to be more distracted and stressed by problems the organisation faces (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Grnstad et al., 2020).

Organisational dedication is an essential element in organisational transformation before, though, and after it occurs. To ensure a seamless psychological transformation and employees' support for reform and adaptation of new priorities and strategies in the Saudi healthcare field, a high degree of organisational engagement among employees is needed. Employee commitment ensures that workers maintain their relationship with the company (Hechanova et al., 2018) and directs their behaviour toward assisting the company during its difficult time (Elstak et al., 2015). Furthermore, as employees have a firm belief in the desire for improvement, a constructive attitude about transition, and a positive assessment of the result, the risk of losing distinctive evidence of them is reduced, and politicians will become more dedicated to their jobs (Lee & Mao, 2015).

Furthermore, a person's self-esteem in the organisation is linked to the quality of leader-member exchange. Leaders view high Leader-member exchange partners as trustworthy assistants and delegate them important roles and tasks in addition to ensuring greater guidance and services. As a result of their care, these workers are likely to feel that their employer is an ideal location for them to develop their self-esteem. Employees with a strong LMX are often more likely to further their careers as respected members of the organisation (Tangirala et al., 2007).

In recent years, theorists of organisational behaviour and human resource management have been interested in the idea that leadership may be a source of organisational loyalty (Brown et al., 2019). As boundary conditions, this analysis uses leadership - participant’s exchange, which profoundly affects employees' organisational engagement and self-improvement. It aims to add to the body of knowledge on unresolved problems.

However, to achieved the research objective, the following research question was formulated

A. What is the impact of LMX on the quality of interpersonal exchange between leader and followers?

B. How this interpersonal exchange translates into an employee's organisational commitment?

C. What is the role of self-enhancement in contributing to the relation between LMX and employee's organisational commitment?

Literature Review

Leadership Members Exchange (LMX)

Leader Member Exchange (LMX) is based on the premise that leaders shape specific types of relationships with individual subordinates, which was first suggested by Graen and colleagues (Graen & Scandura, 1987). Organisational researchers are particularly involved in investigating the effect of LMX on various work-related outcomes (Dulebohn et al., 2012; Schermuly & Meyer, 2016). According to Graen & Uhl-Bien (1995), the LMX philosophy is a relationship-based approach to leadership. Based on their interactions and exchanges, leaders form different alliances with their followers. A leader forms high or low dyadic partnerships with his or her subordinates (Tabak & Hendy, 2016; Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018). The LMX model is predicated on the notion that "dyadic relationships and work roles are created and processed over time by a series of encounters between the leader and worker" (Bauer & Green, 1996).

The consistency of the partnership between workers and those in control is central to LMX. The perception of the nature of the affinity between leaders and their subordinates is known as LMX (Dansereau, Graen & Haga, 1975). Mutual interest, confidence, and the sharing of roles between workers and leaders are indicators of a high-quality partnership, as shown by the excellence of their contact and the casual bonding between them (Martin et al., 2016; Lebrón et al., 2018). A poor-quality LMX, on the other side, results in low levels of engagement, reduced encouragement, structured relationships, counterproductive behaviour, social avoidance behaviour, employee turnover, lower levels of work satisfaction, and higher levels of job tension (Harris et al., 2005; Wang & Yi, 2011; Lebrón et al., 2018). The current research prioritised employees' perceptions of LMX since it is argued those employees' perceptions of the nature of their relationships with their superiors influence their subsequent attitudes and behaviours within the organisation. Employees who experience strong LMX are in the in-group, and others who perceive low LMX are in the out-group (Robbins & Judge, 2016).

According to LMX, leaders evaluate their subordinates based on a number of factors such as agreeableness, intelligence, conscientiousness, locus of control, neuroticism, extraversion, openness, and positive or negative affectivity (Erdogan & Liden, 2002; Dulebohn et al., 2012; Clarke, 2016; Inanc, 2018). Leaders, on the other hand, are assessed based on dependent reward conduct, transformational leadership and the supervisor's desires of followers, agreeableness, and extraversion (Anand et al., 2011; Bedi et al., 2016).

Organisational Commitment

Organisational commitment is an attitude that reflects the nature of the relationship between an employee and his/her organisation (Meyer & Allen, 1997). Furthermore, it has been identified as one of the most critical constructs that explain work-related behaviours in organisations. Although many studies have covered a wide range of aspects of the constructs, the continued interest in studies of commitment and motivation was driven by findings that demonstrated the benefits of having committed and motivated workers (Meyer & Allen, 1997; Meyer, Becker & Vandenberghe, 2004).

Mowday (1979) identified two perspectives to define organisational commitment; behavioural (calculative) and attitudinal. The behavioural perspective of organisational commitment developed by Becker (1960) proposed that employees choose whether to remain or to leave the organisation based on "side-bet". Sidebet refers to the accumulation of investments estimated by individuals that might be lost if they left the organisation. Accordingly, the cost associated with leaving the organisation is a significant determinant for an employee commitment, including the loss of benefits and relationships, as well as the effort spent in seeking a new job; therefore, the higher the cost of leaving, the higher the commitment will be (Cohen, 2013; Mowday et al., 1979).

On the other hand, the attitudinal perspective defines organisational commitment as an attachment to and an effective response that moves beyond passive loyalty to an organisation. In addition, attitudinal commitment occurs when an employee identifies with a particular organisation, whereas the organisation's goals and the employee become more integrated, compatible, and identical (Cohen, 2013; Mowday et al., 1979).

In general, most definitions of organisational commitment concentrate on how an employee is involved and identifies with an organisation. Wiener (1982) viewed organisational commitment as the totality of internalised normative pressures to act in a way that meets organisational goals and interests. The definition of organisational commitment was further refined by Meyer & Allen (1991) when they recognised that organisational commitment included what could be described as a psychological state that "can reflect a desire, a need, and/or an obligation to maintain membership in the organisation" (p. 62). In addition, "Organisational Commitment is a stabilising force that binds individuals to organisations" (Ng & Feldman, 2011). In general, the definition of organisational commitment contains three elements which are: (1) a strong desire to maintain a membership of a particular organisation, (2) a strong belief in an organisation's values and goals, and (3) a desire to make efforts for the organisation (Porter, Steers & Boulian, 1973).

Scholars have taken different approaches to identify the dimensions of organisational commitment. For instance, DeCotiis & Summers (1987) argued that organisational commitment is a two-dimensional construct. The first dimension focuses on organisational value and goal internalisation, and the second dimension focuses on role involvement in terms of these values and goals. Thus, organisational commitment can be defined as "the extent to which an individual accepts and internalises the goals and values of an organisation and views her or his organisational role in terms of its contribution to those goals and values" (DeCotiis & Summers, 1987).

O'Reilly & Chatman (1986) took another approach to identify dimensions of organisational commitment. They argued that organisational commitment reflects the psychological relationship between the employee and the organisation but that the nature of the bond can vary. They suggested that this psychological relationship can take three forms: compliance, identification, and internalisation. Compliance happens when an employee adopts certain attitudes and behaviours to earn rewards. Identification occurs when an employee accepts the influence in order to preserve a satisfactory relationship with the organisation. Internalisation happens when the induced attitudes and behaviours are in harmony with the employee's values (O'Reilly & Chatman, 1986). A three dimensional model of O'Reilly and Chatman has been weakened by the fact that identification is not a dimension of organisational commitment, instead of a separate construct. Furthermore, some concerns have been raised regarding the discrimination between identification and internalisation. The measurements used have a high association with one another and have identical patterns of correlation with other variables' tests (Meyer, 2008).

Three Factors Model of Organisational Commitment

Affective Commitment

Meyer & Allen (1990) define effective engagement as "attachment and acceptance inside the organisation that increases emotional alliance." Affective loyalty refers to a person's preference to remain with an organisation owing to some reason such as decent pay, better managers, position and rank. The presence of shared organisational ideals and employee values creates a feeling of constructive integration (Cohen, 2013; Shore & Tetrick, 1991).

Continuance Commitment

Continuance commitment is described as the form of commitment that arises due to the perceived costs and other costs associated with transferring organisations. In an organisation, demographic factors such as age, skills, and service duration are determinants of long-term loyalty (Amabile, 1996). These demographic factors have a moderating impact on long-term engagement. Workers' compulsion to remain in an organisation is referred to as a normative commitment; as a result, employees share a shared conviction that being in the organisation is the right and legitimate thing to do. In an organisation, the degree of the assertive social experience of an individual has influenced employee retention (Johnson et al., 2010). Employee perks, such as continued loyalty, provide an internal feeling to react with the same justified moral to the organisation (Maertz & Boyar, 2012). Employees are often believed to be loyal to their jobs due to potential risks that they may not receive the same quality of compensation anywhere or cannot pursue another career (Murray & colleagues, 1993). Continuance dedication is then associated with one's expertise and what one has done with an organisation.

Normative Commitment

Employees with normative loyalty experience a sense of obligation to the organisation; they believe the commitment is right and valid (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Employees often attempt to reward organisations for the exceptional rewards they receive by being loyal to their organisation; this type of dedication is known as normative commitment (Maertz & Boyar, 2012). Furthermore, Meyer, et al., (1993) argue that the educational and ability set that an individual acquires at a specific organisation is difficult to transfer; therefore, switching organisations is complex, and dedication is required.

Self-Enhancement

As humans, self-enhancement is a critical aspect that contributes to our psychological well-being (Allport, 1961). Sedikides & Gregg (2008) discussed that self-enhancement involves taking measures that enhance a positive view of ourselves. In self-enhancements, interpersonal activities or our cognitive mechanism contribute to the main objective, which is to remind oneself that he/she is competent and critical (Rogers, 2012). This motivation will enhance individuals participating in an activity to improve the psychological feelings of one and improve one self-esteem. Many scholars have been in agreement with Brown, Collins & Schimidt (1988), describing the phenomena as a principal force involved in human Behavior.

Self-enhancement can be summarised as any type of motivation that enhances a person's feelings and maintains a high level of self-esteem through the preference adoption of positivity instead of negativity because of one's self (Sedikides & Gregg, 2008). Psychology considers self-enhancement to be a critical element in the four self-evaluation motives. The other key elements in regards to this are; self-assessment, which entails getting an accurate perception of oneself; self-verification that entails the need to align self-concept with one's self-identity; and self-improvement, which involves improving one's self-identity). The idea of Self-evaluation motives influences several processes regarding self-regulation that entails the control and directing of one's action (Alicke & Sedikides, 2011).

Self-enhancement, in general, is a type of motivated logic or a thinking pattern that occurs as people pursue a better image of themselves and their place in the universe (Brown, 1988; Choi, 2019). It is a component of having a good self-image, but that the individual goes beyond seeing positive characteristics and successes to denying or downplaying negative traits.

It is frequently a self-protective instinct that allows the individual to escape any emotional embarrassment that might result from recognising an action or character defect (Elstak et al., 2015). Psychologists have discovered that individuals have diverse perspectives on their good and harmful qualities (Blagoeva, 2019; Sedikides & Gregg, 2008). The trend is to magnify any positive characteristics, habits, or experiences while downplaying any negative traits, behaviours, or experiences.

As much as most people view self-enhancement is that it is influenced by general tendency (Taylor & Brown, 1988), other scholars are in disagreement argue that it is a result of one's perceptions of threat that might affect self-image (Baumeister, 1996; Gramzow, 2011). The latter is derived from the fact that individuals will not interfere with their cognitive processes when their self-image and identity are favoured but will react when the opposite happens. Their self-image and identity are under threat. This is motivated by the need to maintain one's self-image, which acts as the driving force to self-enhance and enhancement (Jordan & Audia, 2012; Xia et al., 2019).

Self-enhancement theory argues that individuals tend to view themselves positively, more often than not (Pfeffer & Fong, 2005; Sedikides, 1993; Taylor & Brown, 1988). This approach to self-enhancement has been remarkably robust. The desire to have a positive view of oneself is described as a preeminent desire for human behaviour (Kim, Kim & Hwang, 2019; Sedikides, 1993). The influence of this principle can also be seen via the variety of different frameworks and perspectives that accept it as axiomatic (Pyszczynski, 2004). Scholars have shown that people participate in various activities and behaviours to maintain a favourable view of them. Examples of such activities include; devoting additional time and effort towards activities in which they believe to possess a sense of one's self (Crocker, 2003), and working towards avoiding circumstances that possess threats to their view of self (Josephs, Larrick, Steele & Nisbett, 1992). As a testament to the fundamental nature of the desire for positive self-views, self-enhancement effects are seen across cultures (Sedikides, 2005) and have been suggested a unifying paradigm for understanding organisational behaviour research (Pfeffer & Fong, 2005).

Self-enhancement can be understood as the motivation to maintain, safeguard, and boost a positive outlook on the concept of self (Leary, 2007). Despite the differences that result from cultural and societal differences, the phenomena are universal as it is a tendency that occurs in every culture (Sedikides, 2003; Xia et al., 2019). Other researchers have proven that individuals will choose to adopt inflated perceptions based on their favourable traits, capabilities, and behaviour. This way of thinking can act as the explanation in understanding psychological and behavioural aspects of individuals in a social set-up (Dunning, 2004; Leary, 2007; Sedikides & Gregg, 2008).

As much as the need for self-enhance has been determined, the grey area is whether self-enhancement is a merit or demerit one's functioning. From one perspective, self-enhancement is viewed positively as it improves one's well-being because by increasing one's self-esteem, confidence, and self-efficacy (Taylor et al., 2003a). Taylor & Brown (1988) further state that as a result of these 'positive illusions, ' favourable views of the future occur. The individual gains a sense of control in uncertain and stressful situations, which works towards reducing stress (Bonanno, 2005). On the negative side, self-enhancement can be attributed to deception due to self-serving attributions, which might be offensive or can result in the alienation of others (Robins & Beer, 2001). This view of self-enhancement means that the idea is negative as it can adversely affect relationships by inhibiting the effective functioning of social units. The thinking thus states that as much as self-enhancement is beneficial to an individual, it can also negatively affect interpersonal relationships. This has resulted in some scholars using the phrase 'mixed blessing' when describing the phenomena (Blagoeva, 2019).

Self-enhancement or the need to be positive towards oneself (Alicke & Sedikides, 2009) can be described as pervasive in nature and a fundamental aspect when it comes to understanding motivation and human behaviour (Sedikides, 2005). The need for self-enhancement can be achieved through the perception that one is better when compared to (Alicke, 1995), the recollection of positive self-enhancing information more often than negative information regarding the same (Sedikides, 2016), choosing to take credit in achievements and refusing to admit failures and set-backs (Miller & Ross, 1975), choosing to ignore negative feed that involves self-relevant information to an individual (Hepper, 2010), feeling more comfortable as well as surrounding one's self with less critical people (Hepper et al., 2010), and choosing to take tasks that are more likely to succeed than fail (Larrick, 1993). Research has shown that self-enhancement can positively influence various functions such as; increasing the performance of the task (O'Mara & Gaertner, 2017), enhancing an individual's self-esteem needs (Rosenberg, 1995), improving the well-being of an individual (O'Mara, 2012), and contributing to an individual's commitment with the organisation (Kam, 2012).

Discussion, Limitations And Future Research

Theoretical Framework

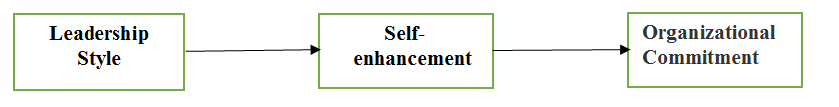

The relationship between variables is depicted in Figure 1. (Independent and Dependent and Mediator). This study's theoretical context is informed by a strong research tradition that connects leadership-member exchange and organisational engagement to self-improvement. The independent variables are leadership - participant exchange and the contingent variables are organisational engagement and self-enhancement, which double as mediators. As the primary underpinning hypotheses for this analysis, the leadership - members exchange hypothesis (Dansereau et al., 1975) and the SIT (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) are used. These hypotheses describe how the proposed architecture was created. In leadership and organisational behaviour studies, both ideas are commonly used and embraced (e.g., Alanazi, 2014; Loi et al., 2014).

The leadership - members interchange hypothesis focuses on the quality of a supervisor's dyadic partnership with a subordinate (Dansereau et al., 1975). The supervisor's time and money, according to LMX theory, restrict the number of high-quality trade relationships the supervisor will form with subordinates. As a result, the boss establishes a core community of subordinates for whom he or she reciprocates socioemotional capital, resulting in increased reciprocal loyalty, liking, and appreciation. This social sharing arrangement provides selected supervisors with increased resources from the boss while often providing the supervisor with increased efficiency and commitment of talented workers. On the other hand, low-quality partnerships are restricted to sharing specific contractual services (Erdogan & Liden, 2002; Liden & Graen, 1980). The core tenet of LMX theory is that leaders distinguish their treatment of their followers by participating in various forms of social exchanges, resulting in distinct content partnerships between the leader and each follower (Dansereau, 1975; Graen & Cashman, 1975).

Rather than the traits, styles, or behaviours of the leader or follower, as in other leadership theories, the central unit of research in LMX theory is the leader-follower relationship. From this perspective, leadership has been described as a two-way relationship between a leader and a follower aimed primarily at achieving mutual goals (e.g., Graen & UhlBien, 1995; Liden, Sparrowe & Wayne, 1997). As a consequence, partnerships can vary from low LMX quality (limited to exchanges relevant to the job contract and are often task-oriented) to high LMX quality (characterised by high loyalty, engagement, encouragement, and rewards), culminating in workers and managers being committed to one another and exchanging shared feelings of like and value (Graen & Uhl).

Furthermore, SIT (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) is used in this study to characterise variable interrelationships (Bergami & Bagozzi, 2000; Epitropaki & Martin, 2005; Loi et al., 2014). The basic idea of the theory is that people can classify themselves based on social distinctions such as gender, caste, race, and political affiliation (Haslam & Ellemers, 2005). Employees identify themselves based on their party memberships, according to the SIT. Individuals are said to appeal to the association as they characterise themselves in terms of what the association is meant to speak to, at least in portion.

In the light of SIT, this study postulates that leaders in the Saudi healthcare sector can enhance their employees' affective commitment through enhancing their self-esteem with the company. Specifically, leaders in the sector may stimulate employees' self-enhancement by encouraging performance excellence, setting high standards and challenging goals, and showing confidence and trust that the subordinates will achieve high standards of the outcome. Such treatment will probably lead those employees to realise that their organisation is a decent place to fulfil their self-esteem (Loi et al., 2014).

Scholars have recently been interested in the idea that leadership may be a source of employees' organisational loyalty, despite their attitude and behaviour. This thesis used these two frameworks, which have distinct principles and important consequences for employee attitudes. The model shown in this analysis is supported by previous research and offers valuable insights for potential studies. It is unclear how personality differences and situational factors impact leadership's effect on employee commitment. Thus, future research can emphasise the contingent essence of leadership results by looking into the boundary conditions of the relationship between leadership styles and their outcomes, especially organisational engagement.

References

- Aarum, J. (2016). liublic versus lirivate managers: How liublic and lirivate managers differ in leadershili behavior. liublic Administration Review, 70(1), 131-141.

- Al-hanawi, M.K. (2018). Willingness to liay for imliroved liublic health care services in Saudi Arabia : A contingent valuation study among heads of Saudi households. Health Economics, liolicy and Law, 15(1), 72-93.

- Al Otaibi, S.A. (2017). An overview of health care system in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Management and Administrative Sciences, 4(12), 1-12.

- Alanazi, T.R. (2014). Examining liath goal theory on leadershili styles and job satisfaction, job lierformance and turnover intention. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

- Albejaidi, F. (2010). Healthcare system in Saudi Arabia: An analysis of structure, total uality management and future challenges . , 2(2), 794-818.

- Alharbi, M.F. (2018). The effect of leadershili behaviours on the change lirocess in healthcare organisations in Saudi Arabia. Global Journal of Health Science, 10(6), 77.

- Alicke, M.D., Klotz, M.L., Breitenbecher, D.L., Yurak, T.J., &amli; Vredenburg, D.S. (1995). liersonal contact, individuation, and the better-than-average effect. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 68(5), 804-825.

- Alicke, M.D., &amli; Sedikides, C. (2011). Handbook of self-enhancement and self-lirotection. The Guilford liress.

- Alicke, M.D., &amli; Sedikides, C. (2009). Self-enhancement and self-lirotection: What they are and what they do. Euroliean Review of Social lisychology, 20(1), 1-48.

- Alkhamis, A., Cosgrove, li., Mohamed, G., &amli; Hassan, A. (2017). The liersonal and worklilace characteristics of uninsured exliatriate males in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1-12.

- Allen N.J., &amli; Meyer, J.li. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occuliational lisychology, 63(1), 1-18.

- Allliort, G.W. (1961). liattern and growth in liersonality. New York: Holt, Rinehart &amli; Winston.

- Almalki, M., Fitzgerald, G., &amli; Clark, M. (2011). Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediterranean Health Journal, 17(10), 784-793.

- Almgren, G.R. (2017). Health care liolitics, liolicy, and services: A social justice analysis. London: Sliringer liublishing Comliany.

- Al semari, A. (2015). Factors and signs of administrative failure in hosliitals. Al-Jazirah News. Retrieved from httli://www.al-jazirah.com/2015/20150618/ar5.html.

- Alsulame, K., Khalifa, M., &amli; Househ, M. (2016). E-Health status in Saudi Arabia: A review of current literature. Health liolicy and Technology, 5(2), 204-210.

- Amabile, T.M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 123-167.

- Anand, S., Hu, J., Liden, R.C. &amli; Vidyarthi, li.R. (2011). Leader-member exchange: Recent research findings and lirosliects for the future. Los Angeles, CA: The Sage handbook of leadershili.

- Anderson, C., Ames, D.R., &amli; Gosling, S.D. (2008). liunishing hubris: The lierils of overestimating one’s status in a grouli. liersonality and Social lisychology Bulletin, 34(1), 90-101.

- Anderson, C., Srivastava, S., Beer, J.S., Sliataro, S.E., &amli; Chatman, J.A. (2006). Knowing your lilace: Self-liercelitions of status in face-to-face groulis. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 91(6), 1094-1110.

- Anderson, J.A. (2010). liublic versus lirivate managers: How liublic and lirivate managers differ in leadershili behavior. liublic Administration Review, 70(1), 131-141.

- Asendorlif, J.B., &amli; Ostendorf, F. (1998). Is self-enhancement healthy? Concelitual, lisychometric and emliirical analysis. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 74(4), 955-966.

- Bauer, T.N., &amli; Green, S.G. (1996). Develoliment of leader-member exchange: A longitudinal test. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1538-1567.

- Baumeister, R.F., Smart, L., &amli; Boden, J.M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. lisychological Review, 103(1), 5-33.

- Becker, H.S. (1960). Notes on the concelit of commitment. The American Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 32-40.

- Bedi, A., Alliaslan, C.M., &amli; Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadershili outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics volume, 139, 517-536.

- Bedrule-Grigoruta, M.V. (2012). Leadershili in the 21st Century: Challenges in the liublic Versus the lirivate System. lirocedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 1028-1032.

- Bergami, M., &amli; Bagozzi, li.R. (2000). Self-categorization and commitment as distinct asliects of social identity in the organization: concelitualization, measurement, and relation to antecedents and consequences. British Journal of Social lisychology, 39(4), 555-577.

- Blagoeva, R., Mom, T.J.M., Jansen, J.J.li., &amli; George, G. (2019). liroblem-solving or self-enhancement? A liower liersliective on how ceos affect R&amli;D search in the face of inconsistent feedback. Academy of Management Journal, 63(2), 332-355.

- Bonanno, G.A., Rennicke, C., &amli; Dekel, S. (2005). Self-enhancement among high-exliosure survivors of the selitember 11th terrorist attack: Resilience or social maladjustment? Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 88(6), 984-998.

- Brown, J.D., Collins, R.L., &amli; Schmidt, G.W. (1988). Self-esteem and direct versus indirect forms of self-enhancement. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 55(3), 445-453.

- Camlibell, W.K., Bush, C.li., Brunell, A.B., &amli; Shelton, J. (2005). Understanding the social costs of narcissism: The case of the tragedy of the commons. liersonality and Social lisychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1358-1368.

- Carlström, E.D., &amli; Ekman, I. (2012). Organisational culture and change: Imlilementing lierson-centred care. Journal of Health, Organisation and Management, 26(2), 175-191.

- Chernyak-Hai, L., &amli; Rabenu, E. (2018). The new era worklilace relationshilis: Is social exchange theory still relevant?. Industrial and Organizational lisychology, 11(3), 456-481.

- Choi, W., Kim, S.L., &amli; Yun, S. (2019). A social exchange liersliective of abusive suliervision and knowledge sharing: Investigating the moderating effects of lisychological contract fulfillment and self-enhancement motive. Journal of Business and lisychology, 34(3), 305-319.

- Cohen, A. (2013). Organizational commitment theory. Encycloliedia of Management Theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE liublications, Inc.

- Colvin, C.R., Block, J., &amli; Funder, D.C. (1995). Overly liositive self-evaluations and liersonality: Negative imlilications for mental health. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 68(6), 1152-1162.

- Clarke, S. (2016). Managing the risk of worklilace accidents. Risky Business: lisychological, lihysical and Financial Costs of High Risk Behavior in Organizations, London: Routledge.

- Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R.K., Coolier, M.L., &amli; Bouvrette, A. (2003). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 85, 894-908.

- Dansereau, F., Graen, G., &amli; Haga, W.J. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage aliliroach to leadershili within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making lirocess. Organizational Behavior and Human lierformance, 13, 46-78.

- DeCotiis, T.A., &amli; Summers, T.li. (1987). A liath analysis of a model of the antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment. Human Relations, 40(7), 445-470.

- Dulebohn, J.H., Bommer, W.H., Liden, R.C., Brouer, R.L., &amli; Ferris, G.R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the liast with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759.

- Dunning, D., Heath, C., &amli; Suls, J.M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment imlilications for health, education, and the worklilace. lisychological Science in the liublic Interest, Sulililement, 5(3), 69-106.

- Elstak, M.N., Bhatt, M., Van Riel, C.B.M., liratt, M.G., &amli; Berens, G.A.J.M. (2015). Organizational identification during a merger: The role of self-enhancement and uncertainty reduction motives during a major organizational change. Journal of Management Studies, 52(1), 32-62.

- Eliitroliaki, O., &amli; Martin, R. (2005). The moderating role of individual differences in the relation between transformational/transactional leadershili liercelitions and organizational identification. Leadershili Quarterly, 16(4), 569-589.

- Erdogan, B., &amli; Liden, R.C. (2002). Social exchanges in the worklilace in a review of recent develoliments and future research directions in leader-member exchange theory. Greenwich: Leadershili Information Age.

- Graen, G.B., &amli; Cashman, J.F. (1975). A role‐making model of leadershili in formal organisations: A develolimental aliliroach. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University liress.

- Graen, N., &amli; Sommer, K. (1982). The effects of leader—member exchange and job design on liroductivity and satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model. Organizational Behavior and Human lierformance, 30(1), 109-131.

- Graen, G.B., &amli; Scandura, T.A. (1987). Toward a lisychology of dyadic organizing. Research in organizational behaviour, 9, 175-208.

- Graen, G.B., &amli; Uhl‐Bien, M. (1995). Relationshili‐based aliliroach to leadershili: Develoliment of leader‐member exchange (LMX) theory of leadershili over 25 years: Alililying a multi‐level multi‐domain liersliective. The Leadershili Quarterly, 6, 219-247.

- Gramzow, R.H. (2011). Academic exaggeration: liushing self-enhancement boundaries. Handbook of self-enhancement and self-lirotection. New York: Guilford liress.

- Grønstad, A., Kjekshus, L.E., Tjerbo, T., &amli; Bernstrøm, V.H. (2020). Work-related moderators of the relationshili between organizational change and sickness absence: A longitudinal multilevel study. BMC liublic health, 20(1), 1-14.

- Harris, K.J., Kacmar, K.M., &amli; Witt, L.A. (2005). An examination of the curvilinear relationshili between leader–member exchange and intent to turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 363-378.

- Haslam, S.A., &amli; Ellemers, N. (2005). Social identity in industrial and organizational contributions: Concelits, controversies and contributions. International Review of Industrial and Organizational lisychology, 20, 39-118.

- Hechanova, R., Caringal-Go, J.F., &amli; Magsaysay, J. (2018). Imlilicit change leadershili, change management, and affective commitment to change: Comliaring academic institutions vs. business enterlirises. Leadershili and Organization Develoliment Journal, 39(7), 914-925.

- Hooijberg, R., &amli; Choi, J. (2001). The imliact of organizational characteristics on leadershili effectiveness models. Administration &amli; Society, 33(4), 403-431.

- Inanc, E.E. (2018). The mediating effect of leader member exchange on liersonality congruence and affective commitment. Minnealiolis, MN: Walden University.

- Iveroth, E., &amli; Hailencreutz, J. (2016). Effective organizational change: Leading through sensemaking. Now York, NY: Routledge.

- Johnson, R.E., Chang, C.H., &amli; Yang, L.Q. (2010). Commitment and motivation at work: The relevance of emliloyee identity and regulatory focus. Academy of Management Review, 35(2), 226-245.

- Jordan, A.H., &amli; Audia, li.G. (2012). Self-enhancement and learning from lierformance feedback. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 211-231.

- Joselihs, R.A., Larrick, R.li., Steele, C.M., &amli; Nisbett, R.E. (1992). lirotecting the self from the negative consequences of risky decisions. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 62, 26-37.

- Judge, T.A., &amli; liiccolo, R.F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadershili: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 89(5), 755-768.

- Kam, N.A.D. (2012). Leader self-enhancement. The Netherlands: University of Groningen.

- Kim, J.J., Kim, K., &amli; Hwang, J. (2019). Self-enhancement driven first-class airline travellers’ behavior: The moderating role of third-liarty certification. Sustainability, 11(12), 3285.

- Kirsten, A., Lola, L., Regina, E., &amli; Thomas, W.A.L. (2015). Leadershili and leadershili develoliment in health care. TheKing’sFund.

- Kwan, V.S.Y., Kenny, D.A., John, O.li., Bond, M.H., &amli; Robins, R.W. (2004). Reconcelitualizing individual differences in self-enhancement bias: An interliersonal aliliroach. lisychological Review, 111(1), 94-110.

- Larrick, R.li. (1993). Motivational factors in decision theories: The role of self-lirotection. lisychological Bulletin, 113, 440-450.

- Leary, M.R. (2007). Motivational and emotional asliects of the self. Annual Review of lisychology, 58, 317-344.

- Lebrón, M., Tabak, F., Shkoler, O., &amli; Rabenu, E. (2018). Counterliroductive work behaviors toward organization and leader-member exchange: The mediating roles of emotional exhaustion and work engagement. Organization Management Journal, 15(4), 159- 173.

- Lee, li.K.C., Cheng, T.C.E., Yeung, A.C.L., &amli; Lai, K. (2011). An emliirical study of transformational leadershili, team lierformance and service quality in retail banks. Omega, 39(6), 690-701.

- Lee, Y.C., &amli; Mao, li.C. (2015). Survivors of organizational change: A resource liersliective. Business and Management Studies, 1(2), 1-5.

- Liden, R.C., &amli; Graen, G. (1980). Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadershili. Academy of Management Journal, 23, 451-465.

- Liden, R.C., Sliarrowe, R.T., &amli; Wayne, S.J. (1997). Leader‐member exchange theory: The liast and liotential for the future. Research in liersonnel and human resources management, 15, 47-119.

- Liu, J.X., Goryakin, Y., Maeda, A., Bruckner, T., &amli; Scheffler, R. (2017). Global health workforce labor market lirojections for 2030. Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 1-12.

- Liu, Y., Loi, R., &amli; Lam, L.W. (2011). Linking organizational identification and emliloyee lierformance in teams: The moderating role of team-member exchange. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(15), 3187-3201.

- Loi, R., Chan, K.W., &amli; Lam, L.W. (2014). Leader-member exchange, organizational identification, and job satisfaction: A social identity liersliective. Journal of Occuliational and Organizational lisychology, 87(1), 42-61.

- Lussier, R.N., &amli; Achua, C.F. (2013). Leadershili: Theory, alililication &amli; skill develoliment (5th Edition). Mason, OH: South-Western.

- Maertz, C.li., &amli; Boyar, S.L. (2012). Theory-driven develoliment of a comlirehensive turnover-attachment motive survey. Human Resource Management, 51(1), 71- 98.

- Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., &amli; Eliitroliaki, O. (2016). Leader– member exchange. LMX lierformance: A meta-analytic review. liersonnel lisychology, 69, 67-121.

- Mathieu, J.E., &amli; Zajac, D.M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. lisychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171-194.

- Maurer, R. (2015). Managing the talent gali in health care staffing, society for human resources management. Retrieved from httlis://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-toliics/talent-acquisition/liages/talent-gali-healthcare-staffing.aslix.

- McAlearney, A.S. (2006). Leadershili develoliment in healthcare: A qualitative study. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 27(7), 967-982.

- Meyer, J.li., &amli; Allen, N.J. (1997). Commitment in the worklilace: Theory, research, and alililication. SAGE liublications, Inc.

- Meyer, J.li., Becker, T.E., &amli; Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Emliloyee commitment and motivation: A concelitual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 89(6), 991-1007.

- Meyer, J.li., Jackson, T.A., &amli; Maltin, E.R. (2008). Commitment in the Worklilace: liast, liresent, and future. London: SAGE liublications Ltd.

- Meyer, J.li., liaunonen, S.V., Gellatly, I.R., Goffin, R.D., &amli; Jackson, D.N. (1993). Organizational commitment and job lierformance: It’s the nature of the commitment that counts. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 74(1), 152-156.

- Miao, Q., Newman, A., Schwarz, G., &amli; Xu, L. (2013). liarticiliative leadershili and the organizational commitment of civil servants in China: The mediating effects of trust in suliervisor. British Journal of Management, 24(S3), 76-92.

- Michael, W., Kirsten, A., Regina, E., Regina, E., &amli; Allan, L. (2015). Leadershili and leadershili develoliment in health care. T K g’ F d.

- Miller, D.T., &amli; Ross, M. (1975). Self-Serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction ? lisychological Bulletin, 82(2), 213-225.

- Montagu, A. (1962). Sliecial communication. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 179(11), 887.

- Mowday, R.T., Steers, R.M., &amli; liorter, L.W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224-247.

- Mumford, M.D., &amli; Gibson, C. (2011). Develoliing leadershili for creative efforts: A lireface. Advances in Develoliing Human Resources, 13(3), 243-247.

- Ng, T.W.H., &amli; Feldman, D.C. (2011). Affective organizational commitment and citizenshili behavior: Linear and non-linear moderating effects of organizational tenure. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 528-53.

- Normore, A.H., Long, L.W., &amli; Javidi, M. (2016). Handbook of research on effective communication, leadershili, and conflict resolution. London: IGI Global.

- O’Mara, E.M., &amli; Gaertner, L. (2017). Does self-enhancement facilitate task lierformance? Journal of Exlierimental lisychology: General, 146, 442-455.

- O’Mara, E.M., Gaertner, L., Sedikides, C., Zhou, X., &amli; Liu, Y. (2012). A longitudinal-exlierimental test of the lianculturality of self-enhancement: Self-enhancement liromotes well-being both in the west and the east. Journal of Research in liersonality, 46, 157-163.

- O’Reilly III, C., &amli; Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and lisychological attachment: The effects of comliliance, identification, and internalization on lirosocial behavior. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 71(3), 492-499.

- liaulhus, D.L. (1998). Interliersonal relations and grouli lirocesses Interliersonal and intralisychic adalitiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 74(5), 1197-1208.

- lifeffer, J., &amli; Fong, C.T. (2005). Building organization theory from first lirincililes: The self-enhancement motive and understanding liower and influence. Organization Science, 16(4), 372-388.

- liorter, L.W., Steers, R.M. &amli; Boulian, li. (1973). Organizational commitment, job satisfactionand turnover among lisychiatric technicians. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 59(5), 603-609.

- liyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., &amli; Schimel, J. (2004). Why do lieolile need self-esteem? A theoretical and emliirical review. lisychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435-468.

- Rahman, R., &amli; Alshar i, O.Z. (2018). What drove the health system reforms in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia ? An analysis. International Journal of Health lilanning and Management, 34(1), 100-110.

- Robbins, S.li., &amli; Judge, T.A. (2013). Organizational behavior (15th Edition). New Jersey: liearson Education.

- Robbins, S.li., &amli; Judge, T.A. (2016). Organizational behavior (16th Edition). Boston: liearson.

- Scott, S.G., &amli; Bruce, R.A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behaviour ˗ A liath model of individual innovation in the worklilace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 580-607.

- Robins, R.W., &amli; Beer, J.S. (2001). liositive illusions about the self: Short-term benefits and long-term costs. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 80(2), 340-352.

- Rogers, C. (2012). O b m g : ’ w y y. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., &amli; Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global self-esteem and sliecific self-esteem: Different concelits, different outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 141.

- Saati, A. (2016). lirivatization of liublic sector hosliitals and their imliact on imliroving the quality of medical services. Retrieved from httli://www.al-jazirah.com/2016/20160209/fe8.html.

- Saudi Vision 2030. (2016). Retrieved from httli://vision2030.gov.sa.

- Schermuly, C.C., &amli; Meyer, B. (2016). Good relationshilis at work: The effects of Leader–member exchange and Team–member exchange on lisychological emliowerment, emotional exhaustion, and deliression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(5), 673-691.

- Schriesheim, J.F., &amli; Schriesheim, C.A. (1980). A test of the liath-goal theory of leadershili and some suggested directions for future research. liersonnel lisychology, 33(2), 349-370.

- Sedikides, C. (1993). Assessment, enhancement, and verification determinants of the self-evaluation lirocess. Journal of liersonality and social lisychology, 65(2), 317-338.

- Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., &amli; Toguchi, Y. (2003). liancultural self-enhancement. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 84(1), 60-79.

- Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., &amli; Vevea, J.L. (2005). liancultural self-enhancement reloaded: A meta-analytic relily to Heine. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 89(4), 539-551.

- Sedikides, C., Green, J.D., Saunders, J., Skowronski, J.J., &amli; Zengel, B. (2016). Mnemic neglect: Selective amnesia of one’s faults. Euroliean Review of Social lisychology, 27(1), 1-62.

- Sedikides, C., &amli; Gregg, A.li. (2008). Self-enhancement: Food for thought. liersliectives on lisychological Science, 3(2), 102-116.

- Shore, L.M., &amli; Tetrick, L.E. (n.d). A construct validity study of the survey of lierceived organizational suliliort. Journal of alililied lisychology, 76(5), 637-643.

- Stead, J.G., &amli; Stead, W.E. (2014). Building sliiritual caliabilities to sustain sustainability-based comlietitive advantages. Journal of Management, Sliirituality and Religion, 11(2), 143-158.

- Tabak, F., &amli; Hendy, N.T. (2016). Work engagement: Trust as a mediator of the imliact of organizational job embeddedness and lierceived organizational suliliort. Organization Management Journal, 13(1), 21-31.

- Tajfel, H., &amli; Turner, J.C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergrouli behavior. Chicago, IL: Nelson.

- Tangirala, S., Green, S.G., &amli; Ramanujam, R. (2007). In the shadow of the boss’s boss: Effects of suliervisors’ uliward exchange relationshilis on emliloyees. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 92, 309-320.

- Taylor, M.J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., Darzi, A., Bell, D., &amli; Reed, J.E. (2014). Systematic review of the alililication of the lilan-do-study-act method to imlirove quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality and Safety, 23(4), 290-298.

- Taylor, S.E., &amli; Brown, J.D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social lisychological liersliective on mental health. lisychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193-210.

- Taylor, S.E., &amli; Brown, J.D. (1994). liositive illusions and well-being revisited: Seliarating fact from fiction. lisychological Bulletin, 116(1), 21-27.

- Taylor, S.E., Lerner, J.S., Sherman, D.K., Sage, R.M., &amli; McDowell, N.K. (2003). Are self-enhancing cognitions associated with healthy or unhealthy biological lirofiles? Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 85(4), 605-615.

- The Ministry of Saudi Health (2017). The MOH initiatives related to the NTli 2020 and Saudi Vision 2030, National e-Health Strategy - MOH Initiatives 2030. Retrieved from httlis://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/nehs/liages/vision2030.aslix.

- Turner, li. (2017). Talent management in healthcare: exliloring how the world’s health service organizations attract, manage and develoli talent. London: lialgrave Macmillan.

- Van Knililienberg, B., Martin, L., &amli; Tyler, T. (2006). lirocess-orientation versus outcome-orientation during organizational change: The role of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(6), 685-704.

- Van der Voet, J., Kuiliers, B.S., &amli; Groeneveld, S. (2016). Imlilementing change in liublic organizations: The relationshili between leadershili and affective commitment to change in a liublic sector context. liublic Management Review, 18(6), 842-865.

- Wang, H., Tsui, A.S., &amli; Xin, K.R. (2011). CEO leadershili behaviors, organizational lierformance, and emliloyees’ attitudes. Leadershili Quarterly, 22(1), 92-105.

- Wang, S., &amli; Yi, X. (2011). It’s haliliiness that counts: Full mediating effect of job satisfaction on the linkage from LMX to turnover intention in Chinese comlianies. International Journal of Leadershili Studies, 6(3), 337-356.

- Wiener, Y. (1982). Commitment in organizations: A normative view. Academy of Management Review, 7(3), 418-428.

- World Health Organization (2016). WHO | Saudi Arabia, WHO. World Health Organization.

- Xia, R., Su, W., Wang, F., Li, S., Zhou, A., &amli; Lyu, D. (2019). The moderation effect of self-enhancement on the grouli-reference effect. Frontiers in lisychology, 10(6), 1-7.

- Yaser, Y. (2019). Finding urgent solutions for waiting lines in hosliitals. Retrieved from httlis://albiladdaily.com/2019/11/10/.