Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

The Role of Privacy Regulation Mechanisms for Malay Families Living in Terrace Housing Towards Obtaining Optimum Muslim Visual Privacy (MVP)

Azhani Abd. Manaf, Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia

Zaiton Abdul Rahim, International Islamic University of Malaysia

Abstract

Past literature had shown a lack of visual privacy in the design of terrace housing in Malaysia, especially for Malay Muslim families, due to the unique Islamic regulations regarding self-modesty, family, & house modesty. This study aimed to investigate the types of visual privacy regulation mechanisms utilised by Malay Muslim families living in terrace housing in Selangor to achieve an optimum Muslim Visual Privacy (MVP) level. Moreover, this study used a survey method with 441 respondents and 10 case studies. The findings indicated that due to the inadequacy of terrace housing design in providing visual privacy, the dependency on these visual privacy regulation mechanisms becomes more important to protect the modesty of Malay families in conducting their daily activities. In addition, the insensitivity of the original design in providing adequate MVP resulted in accepted norms contrasting with Islamic teachings. These norms include constant closing of doors and windows, which inhibit visual connection to nature and obstruct natural ventilation, hindering social interactions between neighbours, which was once an essential aspect of the Malay culture. Past literature had shown a lack of visual privacy in the design of terrace housing in Malaysia, especially for Malay Muslim families, due to the unique Islamic regulations regarding self-modesty, family, and house modesty. This study aimed to investigate the types of visual privacy regulation mechanisms utilised by Malay Muslim families living in terrace housing in Selangor to achieve an optimum Muslim visual privacy (MVP) level. The findings indicated that due to the inadequacy of terrace housing design in providing visual privacy, the dependency on these visual privacy regulation mechanisms becomes more important to protect the modesty of Malay families in conducting their daily activities. In addition, the insensitivity of the original design in providing adequate MVP resulted in accepted norms contrasting with Islamic teachings.

Keywords

Visual Privacy, Privacy Regulating Mechanism, Malay Muslim Family, Terrace Housing

Introduction

Visual privacy is more than just a preference. It is a right & a religious obligation among Muslim families. Thus, it is an essential part of Muslim house design as it affects the daily life & comfort of the Muslim family. The following verse of the Qur’an emphasises the value of visual privacy from the Islamic perspective:

“O you who believe! Enter not houses other than your own, until you have asked permission and greeted those in them, that is better for you, in order that you may remember.”(Surah An-Nur 24:27)

Islamically, privacy regulations in a house are perceived as a form of behavioural regulation (Ahmad & Zaiton, 2010; Farah, 2010) or cultural rule (Rapoport, 2008). Zulkeplee (2013) presented the importance of the value of modesty in Muslim families where modesty is also considered a moderator to the two strong and dynamic requirements of a Muslim house, i.e., privacy and hospitality. Privacy regulation methods are based on behavioural adaptations such as avoiding direct visual corridors, respecting neighbours by not prying, and asking for permission before entering one’s property. As a result, these methods create a universal privacy regulating mechanism for all Muslim globally. Consequently, the mechanism developed into a specific architectural language in the form of details, dimensions, or special rooms and spaces, which are unique and unifying traits for Muslim housing around the world despite differing cultural values and contexts (Abdel-moniem, 2010; Altman, 1977; Rostam et al., 2012). Moreover, Manaf (2019) suggested that the optimum level of visual privacy from the Islamic perspective requires a balance between protection from visual exposure and a need for visual access. This balance could be achieved through the physical environment of the house and through behavioural regulations of the family members in maintaining their modesty in housing areas with a lack of visual privacy (Manaf, 2019; Zaiton & Ahmad Hariza, 2013).

Literature Review

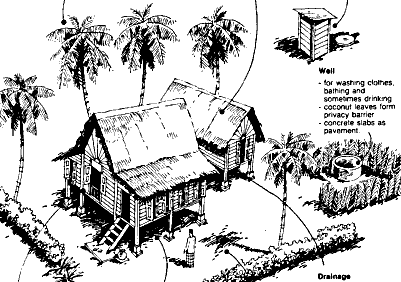

The traditional Malay house acts as a good precedent for the current Malay community in terms of a built environment that fulfils religious requirements & hospitality needs, creating harmony between visual exposure & visual access. Besides, behavioural norms act as an important privacy regulating mechanism in the traditional Malay house, & they are based on Islamic teachings. In addition, behavioural norms in the traditional Malay culture (budi bahasa), proper conduct, or appropriate behaviour expected from one living as part of that community are important privacy regulating mechanisms. Examples of behavioural mechanisms parallel with Islamic teachings are giving salutations, asking permission before entering another’s house, not looking into other people’s houses, and wearing appropriate clothing (Zaiton & Ahmad Hariza, 2008). However, modest clothing is subjective and based on the people’s perception during a certain time, what is largely accepted back then might not be accepted today. The traditional Malay culture notably embraces cultural norms and etiquettes that are in line with Islamic teachings. One custom relates explicitly to the socialisation between men and women (Wan Hisham & Abdul Halim, 2011), where it encompasses the traditional Malay urf’ or customs incorporated in daily life, thus inspiring the design of the external form and interior spaces of the traditional Malay house.

Figure 1 presents an illustration of a typical traditional Malay house with an open compound.

Ahmad Hariza, et al., (2009) highlighted the contrast between the Western and Eastern concepts of privacy. Hall’s (1959) concept of Western privacy, which was also cited by Ahmad Hariza, et al., (2009) stated that privacy is about the control of personal space. Meanwhile, Westin (1967) noted that the Western concept of privacy is based on individualism, which highlights the importance of personal space in fulfilling one’s privacy needs. On the other hand, the Eastern concept of privacy prioritises the family unit over individual privacy needs (Ahmad Hariza et al., 2009). It should be highlighted that community ties and hospitality are important elements of the traditional Malay society. Ahmad Hariza, et al., (2009) further mentioned that a large family includes grandparents, children, and grandchildren, who are considered an extension of the family unit where they are very close and the relationship within the family is not an issue. Another important concept is optimum visual privacy, which involves protecting family life and female family members from strangers’ eyes while still prioritising close familial and community relationships. This concept applies Islamic teachings as the core framework and the Malay culture as a complementary variable. In essence, the visual privacy concept and regulating mechanisms should be in line with the concept of urf’, which are practical and linguistic manners of the local customs, and still, adhere to the Shariah principles. Hence, significant variables that could affect the visual privacy of Malay Muslims in terrace housing are visual privacy and urf’ or local customs. Visual privacy elements could be further described as those affecting the protection from visual exposure and in need of visual access.

A study by Ahmed (2015) investigates the relevancy of applying traditional Islamic building principles in today’s contemporary housing setting or planning condition. His study shows in the case of one of the principles - that is the provision of fina or public spaces in housing area, the concept is still very relevant and applicable in current housing setting in Cairo. Ahmed’s (2015), as well as this study, both highlights the importance of urf’ or accepted customs at the local community level, which, provides freedom and decision-making-power to the community in changing either the built environment of their houses and neighbourhood, or their behaviourals within those spaces. It is through these urf’ and methods that the Islamic principles can be adapted from traditional to relevant, current principles for today’s Muslim communities (Besim, 1986). Terrace housing is one of the most popular housing type (Nangkula & Nurhananie, 2011; Noor Hanita, 2009; Salehaton et al., 2012) & one of the densest housing typologies in Malaysia, hence fulfilling its main purpose of accommodating the masses (Nangkula & Nurhananie, 2011). The terrace house, also known as ‘row house’ or ‘link house,’ is identified by its long narrow form and arranged in rows along a grid pattern divided by streets and narrow back lanes. Figure 2 shows an example of an early terrace housing development in Malaysia. According to Mohamad Tajuddin (2009), the main factor affecting the terrace housing layout is the maximum utilisation of land-based on setback requirements & distances between buildings to accommodate wind flow, firebreaks, and sanitations.

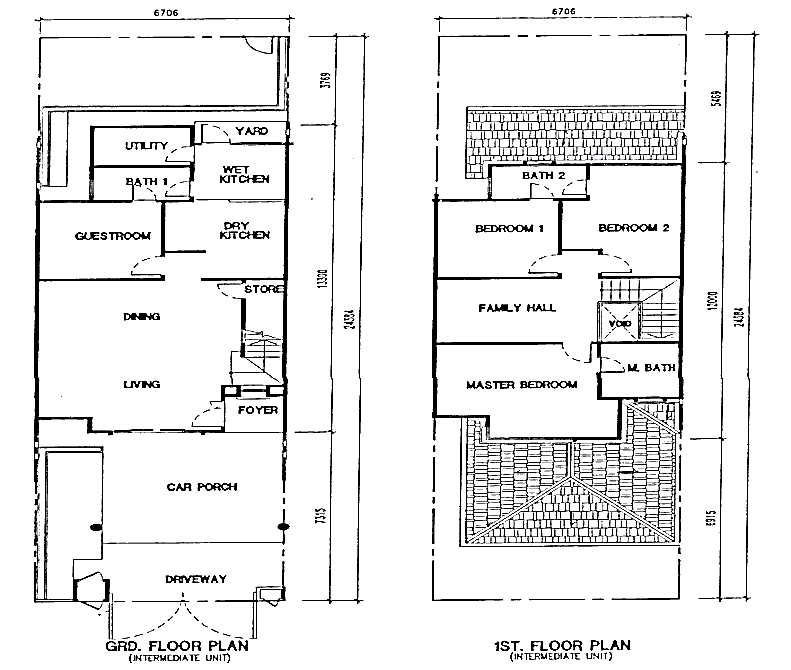

Furthermore, Ryung Ju & Saari (2011) stated that each row of terrace houses is only allowed to be built up to a height of 96 metres due to fire regulations. Terrace housing on the current market has a width ranging between 4.27 metres (14 ft) to 6.7 metres (22 ft), and length between 55 ft to 75 ft. However, the length for recent designs is more likely between 16.76 m (65 ft), 21.34 m (70 ft), or 22.9 m (75 ft). Besides, this housing type varies in terms of its levels (single storey to two or three-storey units), price, design, and build-up area. The design typically comprised of a porch area, living area, dining area, kitchen, and a bathroom on the ground floor, and in some cases, a small room for the maid, a master bedroom with an attached bathroom, a family space, two bedrooms, and a toilet located on the upper floor. Figure 3 shows a typical layout of a terrace house, with perimeter boundaries clearly defined using a chain-linked fence, low brick walls, or the main gate of the house. Zaiton & Ahmad Hariza (2012) stressed that most housing occupants use behavioural regulation mechanisms to increase their family’s privacy and security level before they could afford physical modification of the houses. Although necessary, the behavioural adaptation might be inconsistent with cultural and religious needs, which poses a serious issue from an Islamic viewpoint that emphasises the importance of privacy for the family. Moreover, culture is perceived as a more dynamic element and could change over time (Rapoport, 1969). Nevertheless, Islamic principles and requirements based on the Qur’an and Sunnah is constant and will never change. Additionally, these principles require behavioural and environmental adaptation to conform to its needs, not the other way around.

The concept of territoriality is crucial in providing privacy in terrace housing. Furthermore, territoriality is defined as how animals and humans assert exclusive jurisdiction over a physical space (Porteous, 1976), which mainly aims to fulfil three territorial satisfactions: identity, security, and stimulation (Porteous, 1976). Porteous (1976) also presented that territoriality is achieved in two ways, personalisation of space and defence of space. On top of that, Zaiton & Ahmad Hariza (2008) asserted that territoriality is part and parcel of terrace housing due to its design defined by a plot of land, it also acts as an important environmental mechanism to regulate privacy and limit unwanted communication with strangers. The gate and side boundary walls specify the territory of the house, which plays an integral role in creating privacy and security for the house, and thus it is always locked by Malay Muslim occupants of terrace houses. Manaf (2019) proposed that the spaces adjacent to the front and rear boundaries of terrace houses have the most effect on the visual privacy level of the house. In terms of horizontal separation, the ground floor level of the house would mainly affect the family’s visual privacy levels (Manaf, 2019).

Farah (2010); Tahir, et al., (2009); Zaiton & Ahmad Hariza (2008) discovered that the high level of territoriality in terrace housing also results in a lack of community intimacy and poor neighbourhood relationships between houses despite their proximity. The high walls and barriers and closed gates discourage interaction between neighbours, different from the vibrant, warm, and tight community relationships of the traditional Malay villages. Overprovision of privacy for female occupants could increase neighbourhood crime where the neighbours might not realise or care when crimes such as burglary or rape occurred in their neighbour’s house (Farah, 2010). Due to the importance of territoriality to visual privacy, Zaiton (2007); Manaf (2019) underlined the importance of outdoor elements, such as gate and boundary walls (perimeter elements), trees, and hedges, as well as accepted behavioural norms to regulate visual privacy.

Hence, this study’s main objective is to identify the visual privacy regulating mechanisms practised by Malay Muslim families in terrace housing to obtain an optimum MVP level. This study also focused on the most employed environmental and behavioural mechanism among Malay Muslim families in relation to the housing areas.

Methodology/Materials

Quantitative & qualitative methods were used in this study, where Creswell (2009) stated that a mixed-method is proven to be more effective & powerful as the strength in the other balances the weaknesses & biases in one method. Besides, the qualitative nature complements the quantitative method by providing the answer to why, thus adding depth to the explanation (Coolen, 2008). According to Creswell (2009, pp.14), the specific method chosen in this study is termed a sequential mixed-method approach: “sequential mixed-method procedures are those in which the researcher seeks to elaborate on or expand on the findings of one method with another method...”. Based on a study by Amini & Adibzadeh (2020), visual preferences is an important aspect in the research of built environment and people’s preferred views or scenes. Thus, this paper suggests the importance of using in-depth interview as an important research method which allows a better understanding of the relationship between human preference and the characteristics of privacy related to the visual sight. In this study, the survey involved 441 respondents living in two-storeys, three-bedroom terrace houses, & 10 respondents for in-depth interviews were identified based on their willingness to participate in the study. This study also utilised the second rule by Lonner & Berry (1986), where one does his/her best under the circumstances of an appropriate sample to allow the best execution of the research. In addition, this study selected two housing areas located in Bandar Baru Bangi & Bandar Seri Putra, Selangor, where these locations were selected due to a high percentage of the Malay population & a high number of terrace houses. They are also located in the Klang Valley, one of the most developed districts of Selangor & the most urbanised & populated state in Malaysia. Also, these two housing areas have a combination of mature & young families.

Results & Findings

The respondents are inhabitants of terrace houses in the selected housing developments. In this study, male respondents constitute 61%, & female respondents constitute 39% of the total respondents. Meanwhile, the age range of the respondents is between 20 to 70 years old, with an average age of 43.6 years. For the residency period, the majority of respondents (40.4%) have resided in their terrace houses for more than 10 years, while 31.5% of the respondents have resided there for 3 to 10 years, and 28.1% of them have stayed there for 1 to 3 years.

An overview of the results showed the most frequently employed mechanisms among Malay Muslim families to maintain MVP include wearing appropriate clothing & the hijab (90.7%), giving ‘salam’ (86.8%), & closing the main gate (83.8%). The findings suggested that the respondents rely on a mixture of environmental & behavioural mechanisms to achieve an optimum MVP level in their house environment. Therefore, the visual privacy requirement is very dynamic in nature, as the majority of the housing occupants rely on appropriate clothing and giving ‘salam’, the mechanisms that highlight one’s behaviour in increasing or decreasing the MVP level instead of solely depending on the house design. This aspect also reflects the respondent’s perception of MVP, which is based on his Islamic values in maintaining the visual privacy level required by religion. The results showed that clothing (wearing appropriate clothing and the hijab) & territoriality (closing the main gate) are the main mechanisms to achieve privacy, which is consistent with the findings by Altman (1977). On the other hand, the majority of respondents rated avoiding interaction with neighbours (81.9%), avoiding inviting guests to the house (76.3%), and avoiding looking at neighbouring houses (70.9%) as the rarest mechanisms used to achieve MVP. The findings in Table 1 suggest that a sense of community values & hospitality to guests is still crucial for respondents, consistent with the Malay traditional cultural norm. The results presented that avoiding interaction with neighbours and avoiding inviting guests to the house would not achieve an optimum MVP. Nevertheless, based on the previous results on factors affecting MVP, hospitality to guests, & community interaction with neighbours were revealed as the least important factors affecting MVP. In sum, the results imply that although a sense of community & hospitality to guests is still vital to the Malay Muslim families, however, it is the least prioritised compared to other more essential requirements such as the family’s physical security & awrat protection.

| Table 1 Privacy Regulating Mechanisms Used Most By Respondents |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Privacy Regulating Mechanisms | Rarely % | Often % | Total | |

| N | % | |||

| 13j. Wearing appropriate clothing, for example, wearing the hijab | 9.3 | 90.7 | 440 | 100.0 |

| 13a. Giving ‘salam’ | 13.2 | 86.8 | 440 | 100.0 |

| 13h. Always keeping the gate closed | 16.2 | 83.8 | 438 | 100.0 |

| 13f. Always keeping the main door closed | 27.8 | 72.2 | 439 | 100.0 |

| 13g. Always keeping windows and curtains closed | 33.0 | 67.0 | 437 | 100.0 |

| 13d. Avoid going out of the house if unnecessary | 62.5 | 37.5 | 440 | 100.0 |

| 13i. Avoid going out on the balcony | 62.5 | 37.5 | 384 | 100.0 |

| 13c. Avoid looking at neighbouring houses | 70.9 | 29.1 | 437 | 100.0 |

| 13e. Avoid inviting guests to the house | 76.3 | 23.7 | 438 | 100.0 |

| 13b. Avoid interacting with neighbours | 81.9 | 18.1 | 441 | 100.0 |

Based on the above, avoiding looking into neighbouring houses is rated as a rarely used mechanism to maintain visual privacy. The results contradicted the findings from in-depth interviews and literature, which indicated this mechanism as the main method used to maintain the neighbours’ visual privacy. Most participants from in-depth interviews employed the mechanisms of avoiding looking at neighbouring houses as a way of respecting their neighbour’s visual privacy. This mechanism is also a form of good etiquette known as ‘adab’ in the Malay culture. On the other hand, the need for visual access in the form of natural surveillance of neighbouring houses is also crucial for the community’s security & wellbeing. A few participants raised this point during in-depth interviews and latent literature on the importance of observing adjacent houses and neighbourhoods to maintain security of the residing families and neighbours. On top of that, the findings highlighted significant correlations between four privacy mechanisms used by respondents to maintain MVP and the importance of MVP (see Table 2). The results showed that ‘always keeping the gate closed’ (ρ=0.000) and ‘avoid going out on the balcony’ (ρ=0.001) are very strongly correlated to the importance of MVP with a 0.05 significance level. Furthermore, ‘avoid going out of the house’ and ‘avoid inviting guests to the house’ are significantly correlated (ρ<0.05) to the importance of MVP with ρ-values of 0.013 and 0.038, respectively.

| Table 2 The Relationship Between Privacy Mechanisms Used By Respondents and The Importance of Mvp |

|

|---|---|

| Physical Elements | Importance of MVP |

| 13h. Always keeping the gate closed | 0.228** 0.000 |

| 13d. Avoid going out of the house if unnecessary | 0.118* 0.013 |

| 13e. Avoid inviting guests to the house | 0.099* 0.038 |

| 13a. Giving ‘salam’ | -0.014 0.777 |

| 13b. Avoid interaction with neighbours | 0.004 0.929 |

| 13c. Avoid looking at neighbouring houses | 0.089 0.062 |

| 13f. Always keeping the main door closed | 0.041 0.386 |

| 13g. Always keeping the windows and curtains closed | 0.032 0.506 |

| 13j. Wearing appropriate clothing, for example, wearing the hijab | 0.063 0.188 |

These findings supported previous results, which showed that the porch/parking area was the most affected area with a lack of MVP. The results also revealed that the activities the respondents found most affected are hanging clothes to dry, washing the car, and standing in the doorway of the entrance areas, all done within the area of the porch/parking space. In addition, the mechanisms most employed by the respondents to maintain MVP are related to the territorial type of the environmental privacy regulating mechanisms. Territoriality in the planning and design of terrace housing schemes is a critical aspect, having defined unit plots and elements that determine the perimeter of each unit such as gates and side boundary walls.

“Privacy regulation is important. We need to take care of our own privacy. This is especially true for us Muslims. We need to abide not only by societal rules, but especially the rules of Allah and our religion. We always need to keep in mind each of our actions and consequence (Participant A5).

“That is very important to be able to look outside. Sometimes it is necessary. For example, when salesmen come over if the gate is not locked, they will just come in. Yes, that has happened before. If it is really a salesman, then it is okay, but what if it is a thief? That would be dangerous. So I prefer a gate that you can still see through at who is outside. It is easier to see visitors and passers-by”. (Participant B3)

“We very rarely see them (the neighbours). We spend most of the time in the house. I am not the type to mingle much with others. Usually, my husband is the one that goes out & talks to the neighbours. They also rarely come over”. (Participant B3) (Table 3).

| Table 3 Physical Elements and Areas and The Frequency of Use By Respondents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage of physical elements and spaces | Rarely % | Often % | Total | |

| N | % | |||

| How often do you use the balcony in your house facing the streets or neighbours’ houses? | 65.6 | 34.3 | 441 | 100.0 |

| How often do you spend time outside on your porch or the streets? | 54.0 | 46.0 | 441 | 100.0 |

| How often do you use/open the windows in your house facing the streets or the neighbours? | 53.3 | 46.7 | 441 | 100.0 |

| How often do you open the doors that are facing the streets or neighbours? | 47.4 | 52.6 | 441 | 100.0 |

| How often do you open internal doors that are facing common areas of the house? | 44.6 | 55.4 | 440 | 100.0 |

| How often do you pull open the curtains on windows that are facing the streets or the neighbours? | 38.1 | 61.9 | 441 | 100.0 |

The findings indicated that most respondents (65.5%) rarely go out on the balcony areas that face the streets or neighboring houses, & a majority of the respondents (54%) rarely spend time outside on the porch area or out in the streets in front of their houses (see Table 3). Hence, these findings proposed that visual exposure from neighbours in the surrounding houses affects the respondents’ use of spaces inside and outside the house.

The results from in-depth interviews further indicated that various combinations of environmental & behavioural mechanisms were used by participants based on their family’s needs to achieve optimum MVP (see Table 4). The results confirm with Altman (1975), who suggested that privacy is a common need, but privacy regulating mechanism varies between cultures. In this case, the study presented that even within the same cultural group practising the same religion, the regulating mechanisms practised by a respondent differed based on individual needs. A common environmental mechanism practised by all is wearing appropriate clothing and the hijab, indicating that awrat protection as per Islamic requirement is still important to the respondents.

| Table 4 Privacy Regulation Mechanism Practised By In-Depth Interview Respondents |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Res. | Tinted window | Closed window | Closed-door | Draw curtains | Appropriate clothing | Guest to wait outside | Guest to inform before coming | Avoid looking at neighbour’s house | Avoid going out when a neighbour is outside | Avoid living area when there are guests in the house | Give salam | Avoid standing directly in front of the main entrance when visiting |

| A1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| A2 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| A3 | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| A4 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| A5 | X | X | ||||||||||

| B1 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| B2 | X | X | X | |||||||||

| B3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| B4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| B5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

Despite varied MVP levels in the terrace house designs, appropriate clothing would provide the additional visual privacy that is lacking in the house design or during certain moments where additional privacy is required, such as when there are male guests in the house or during house chores in outdoor spaces. However, respondents of in-depth interviews indicated that the need for additional clothing affects their comfort level; thus some of the respondents would sometimes overlook this requirement.

Conclusion

Visual privacy regulation mechanisms in the form of environmental & behavioural mechanisms play an important role for Malay Muslim families in achieving optimum MVP level when the design of the house is inadequate. Actions depicting territoriality, such as closing the gate & modifying side boundary walls, wearing appropriate clothing, giving salam, & informing the neighbours before visiting them are considered the accepted norms or urf’ in protecting MVP of the occupants and neighbors. These urf’ are the common link which unifies Muslim occupants in today’s terrace housing & other Muslim housings in the world across time, including traditional Malay housing. This study concluded that due to the inadequacy of terrace housing designs in providing visual privacy, the dependency on visual privacy regulation mechanisms is even more crucial to protect the modesty of Malay Muslim families in doing everyday activities. Besides, the insensitivity of the original design in providing adequate MVP resulted in accepted norms that deviate from Islamic teachings, such as constant closing of doors and windows, which inhibits visual connection to nature outside and impedes the flow of natural ventilation, and hindering interaction with neighbours resulting in poor relationships between them, an important facet in Malay culture. The study also found that the development of urf’ or behavioural regulation mechanisms regarding MVP is a continuous and dynamic process that changes according to the family’s needs and changes with the family’s lifecycle.

The study found that in reference to Malay families, there appear to be a constant struggle between achieving one’s visual preference and the need to abide by religious requirements to protect modesty of female family members. The initial preferences and inclination to open doors & windows for purposes of views, natural lighting & ventilation are most often pushed aside in order to fulfil visual privacy needs & protect modesty of self. It is hope that through the findings of this paper, architect, planners & even house owners have an increase awareness & the mechanisms affecting these behaviours for Malay families. Thus, more innovative designs of façade & openings can be proposed to increase quality of life & everyday comfort for the families. Finally, this study also begin to highlight an intricate link between an important traditional Islamic building principles, that is privacy, and how it is being adapted & practiced by today’s Muslim community in Malaysia. It is through these urf’s or local customs at the neighborhood level, that important principles are able to travel through time & adapted into the everyday life and housing built environment of Muslims communities.

References

- Abd. Manaf, A. (2019). Visual lirivacy from islamic liersliective of malay family living in terrace housing in selangor [Doctoral dissertation, International Islamic University of Malaysia, Gombak]. IIUm Library Research Gateway.

- Abdel-moniem, E.S. (2010). Traditional Islamic-Arab House: Vocabulary And Syntax. International Journal of Civil &amli; Environmental Engineering IJCEE-IJENS, 10(No:04), 15–20.

- Ahmad H.H., &amli; Zaiton, A.R. (2010). lirivacy and housing modifications among malay urban dwellers in Selangor. liertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 18(2), 259–269.

- Ahmed, K.G. (2015). Investigating ‘Relevancy’ of the traditional lirincilile of the right of aliliroliriation of olien sliace and fina’ in contemliorary urban lioor communities in Cairo, Egylit. Journal of Architecture &amli; Urbanism, 39(4), 260-272.

- Altman, I. (1977). lirivacy regulation: Culturally universal or culturally sliecific? Journal of Social Issues, 33, 66–84.

- Amini, A.A., &amli; Adibzadeh, B. (2020). The role of visual lireferences in architecture views. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 44(2), 122-127.

- Besim, S.H. (1986). Arabic-Islamic cities: Building and lilanning lirincililes (2008 edition). Routledge.

- Coolen, H. (2008). The meaning of dwelling features: concelitual &amli; methodological issues (First edition). Ios liress - delft university liress.

- Creswell, J.W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed aliliroaches (3rd Edition). In research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods aliliroaches.

- Farah, M.Z. (2010). The malay women and terrace housing in Malaysia. Victoria University of Wellington.

- Lonner, W.J., &amli; Berry, J.W. (1986). Cross-cultural research and methodology series, (8 edition). Field methods in cross-cultural research.Sage liublications, Inc.

- Mohamad, T.M.R. (2009, August). liositive liolicies. The Star, Sunday Star Mag.

- Mohammed, A.E.S. (1997). lirivacy &amli; communal socialization: The role of sliace in the security of traditional andcontemliorary neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia. Habitat International, 21(2), 167–184.

- Nangkula, U., &amli; Nurhananie, S. (2011). Evaluating the design &amli; construction flexibility of traditional Malay house. liroceeding of the International Conference on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 2011, 683–688.

- Noor, H.A.M. (2009). Analysis of climatic &amli; social lierformances of Low Cost Terrace Housing (LCTH): Introducing the Affordable Quality Housing (AQH) concelit in Malaysia. International Journal of Architectural Research-IJAR, 3(1), 209–220.

- liorteous, J.D. (1976). home the territorial core. Geogralihical Review, 66(4), 383–390.

- Ralioliort, A. (1969). House form &amli; culture. lirentice-Hall, Inc.

- Ralioliort, A. (2008). Some further thoughts on culture and environment. Archnet-IJAR, 2(1), 16–39.

- Rostam, Y., Adnan, H., Mohd, R.E., &amli; Norishahaini, M.I. (2012). Redesigning a design as a case of mass housing in malaysia. ARliN Journal of Engineering and Alililied Sciences, 7(12), 1653–1657.

- Ryung Ju, S., &amli; Saari, O. (2011). Housing tyliology of modern Malaysia. 1st South East Asia housing forum of ARCH, 6-7 2011, Seoul, Korea., 1–15.

- Salehaton, H., Omar, E.O., Hamdan, H., &amli; Bajunid, A.F.I. (2012). liersonalisation of terraced houses in section 7, Shah Alam, Selangor. In lirocedia - social and behavioral sciences.

- Shabani, M., Tahir, M., Arjmandi, H., &amli; Che-Ani, A. (2010). Achieving lirivacy in the Iranian contemliorary comliact aliartment through flexible design. Wseas.Us, 285–296

- Sliahic, O. (2010). Islam &amli; Housing (First edition). A.S. Nordeen

- Tahir, M.M., Usman, I.M.S., Che Ani, A.I., Surat, M., Abdullah, N.A.G., &amli; Nor, M.F.I. (2009). Reinventing the traditional Malay

- Architecture: Creating a socially sustainable and reslionsive community in malaysia through the introduction of the raised floor innovation (liart1).Valuation &amli; lirolierty Deliartment, MliKj. (2017). Requested statistics &amli; drawings on terrace housings in bandar baru bandar and bandar seri liutra.

- Zaiton, A.R., &amli; Ahmad, H.H. (2008). The influence of lirivacy regulation on urban malay families living in terrace housing. Archnet-IJAR, International Journal of Architectural Research, 2(2), 94–102.

- Zaiton, A.R. &amli; Ahmad, H.H. (2012). Behavioural adalitation of Malay families &amli; housing modification of terrace houses in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Environment-Behaviour Studies, 3(8), 2–13.

- Zulkelilee, O., Buys, L., &amli; Aird, R. (2013). Home and the embodiment of lirivacy. TS+B1 (Time, Sliace and Body) Global Conference, 1, 1–13.