Research Article: 2023 Vol: 29 Issue: 2S

Theory Selection and Applications for Immigrant Enterprises, Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurship (IEEE) Research

Carson Duan, University Of New England

Citation Information: DUAN, C. (2022). Theory selection and applications for immigrant enterprises, entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship (ieee) research. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 29(S2), 1-18.

Abstract

Five decades of research into immigrant enterprises, entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship (IEEE) call for a synthesis of the field to note the theories and matching applications. The paper aims to fill this literature gap in IEEE field by improving and synthesizing existing knowledge and establishing a clear picture for IEEE study. The paper argues that it is important to choose appropriate theories to guide the research design and inquiry procedure, and thus the comprehensive interpretation of the results in this multi- or inter-disciplinary literature of IEEE research. This paper synthesizes traditional and contemporary theories with their application conditions. Authors argue that since IEEE research needs to be conducted with numerous disciplines such as economics, sociology, anthropology, entrepreneurship and business studies, and the chosen theories need to be logically matching the researchers, conceptual frameworks, investigation questions, data collection and analysis methods. The findings contribute to the immigrant business, management and social science researchers, in particular for higher degree research students.

The research follows the procedure of the theory-context-characteristics-methodology literature review; it utilizes a well-accepted process analytical framework that indicates three phases (motivation, strategies and outcomes) in the IEEE process. Drawing on the framework, IEEE is determined by personal and environmental characteristics, including personal traits, socioeconomic, human capital, cultural, institutional, and many other influential dimensions. Therefore, the theory application in IEEE studies must be from multi- or inter-disciplinary perspectives with correct theory approaches.

The IEEE study process can be either objective or subjective with an inductive or deductive approach; with these objectives, researchers are able to select the best matching theories and apply them in to the research. The paper argues that the key to discovering the nature of knowledge in the field is to apply the best match theories for appropriate projects. From the discussions, it is apparent that theories as positions to explain the phenomena significantly impact research projects’ success. Thus, the choice of a theory infers a near certitude about a particular study that comes from a specific combination of researchers, targets and related environmental factors. This relationship is significant because the theoretical implications of theory choice suffuse the research question/s, participants’ choice, data collection implementation and collection processes, and data analysis. It should be noted that theories can be combined in one research project. This paper provides a clear understanding of the different aspects of the commonly used theories and conditions for application. The paper can be a handy reference for all researchers.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Immigrant, Dual Entrepreneurial Ecosystem, Immigrant Entrepreneurial Ecosystem.

Introduction

In today’s increasingly interconnected world, international migration has touched nearly all of its corners (UN, 2019). Modern transportation has made it easier, cheaper and faster for people to move to other countries in search of jobs, opportunities, education and quality of life. The United Nations International Migrant Report (2019) noted that the number of international migrants worldwide has continued to grow rapidly in recent years, reaching 258 million in 2017 and 272 million in 2019, up from 220 million in 2010 and 173 million in 2000 (International Organization for Migration [IOM], 2020). The UN report further stated that the growing trend of international migration would continue in the foreseeable future. Globalization not only enables individuals to move internationally more easily but also facilitates faster growth in international migration and cross-border activities, including capital transfer, technology spread, goods trade, service provision and culture diffusion. The IOM also emphasized the growing connections among people and countries due to global immigration trends.

Immigrant enterprises, entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship (IEEE) are recognized as an integral part of socioeconomic development and a crucial component of the support programs for immigrants. Evidence for these outcomes can be found in studies reporting on IEEE in Europe and North America. In the United States (U.S.), statistics have revealed that, although immigrants make up only 13% of the total population, they account for 27.5% of all entrepreneurs (Vandor & Franke, 2016). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reported for the United Kingdom (U.K.) that people with migrant backgrounds are twice as likely as their white British counterparts to be early-stage entrepreneurs (Hart, Bonner, Levie, & Heery, 2018). Vandor and Franke (2016) stated that about one-fourth of all engineering and technology companies started between 2006 and 2012 in the U.S. had at least one immigrant co-founder. According to Gould’s calculation, based on immigration numbers and transnational trade data in the U.S., the increase in immigrants has a direct impact on international trade in the host country, and the market size of the home country is directly linked to the success of immigrant entrepreneurship. Furthermore, in Australia and New Zealand (NZ), ventures established through cooperation between born-native and immigrant firms tend to expand faster internationally than ventures by natives, which stems from the synergistic effect of the combined knowledge bases (Lin et al., 2018). Describing the success of immigrant entrepreneurship in the U.S., the Department of Small Business Administration (SBA) stated that:

By virtue of having left their native land, they may have entrepreneurial inclinations. Their outsider status may allow them, in some cases, to recognize “out-of-the-box” opportunities that native-born individuals with similar knowledge and skills do not perceive. These capabilities may be linked to unique entrepreneurial resources, such as access to partners, customers, and suppliers in their countries of origin (Hart et al., 2011).

Factors that account for the increasing interest in entrepreneurship among immigrants compared to born-natives include a higher level of entrepreneurial motivation among immigrants (Kerr & Kerr, 2019). In addition, as a strategy for sustainable socioeconomic development, many governments have established programs to attract immigrant entrepreneurs to their countries. An example is the Project for the Promotion of Immigrant Entrepreneurship (PEI) in Europe. In many developed countries, the entrepreneurial environment for immigrants, in terms of business regulations and immigration policies, has continuously improved over the last three decades. Immigrants’ entrepreneurial capability, however, is still lagging behind the goal of “[creating] economic opportunities for all, with the purpose of leaving no one behind”, which is among the top priorities of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UNCTAD, 2018). One mechanism to achieve this agenda is through the promotion of entrepreneurship among immigrant groups.

Immigrant entrepreneurship, then, is a worldwide phenomenon, particularly in developed countries, and is worth in-depth research both theoretically and empirically. The number of scholars who are interested in the area has increased exponentially since the 1960s. As a young academic discipline, however, IEEE research has gaps from strategic, theoretical and empirical standpoints. From the research strategy perspective, as Collins and Low (2010) pointed out, “the literature on entrepreneurship often ignores the study of immigrant or ethnic entrepreneurship.” Kerr and Kerr (2019) noted that, although early work on IEEE has addressed many important issues, insufficient attention has been paid to the big picture and in-depth studies are few. From a research methodology standpoint, it is clear that the individual level of analysis is commonplace. Thus, argued that future investigations should take meso- and macro-level factors into consideration, given the importance of institutional context to the promotion of IE.

So far, IEEE research has centered on the individual, the immigrant community and the host society. From the home-country perspective, scholars have only examined some individual factors in different studies, thus the existing studies lack a holistic approach. Sometimes the home country is treated as a socio-economic-political system, but there is a lack of clarity concerning the factors in the home country ecosystem that impact IE. Moreover, there is no comprehensive framework that analyses the combined effects of factors from the host country (including the co-ethnic community), home country, individuals and their firms on IE.

Scholars have also recognized that the IEEE phenomenon originates mainly from changes to immigrants’ personal environment as a result of migrating from their home county to the host country, as they find themselves in a new and very different environment. According to the resource-based view, entrepreneurs do not literally “create something from nothing.” Apart from human and social capitals, they need financial capital to start and run their businesses.

The UN Conference on Trade and Development identified two broad antecedents of IEEE: the individual and the socioeconomic and political environments (UNCTAD, 2018). Some scholars even asserted that “studying entrepreneurs as individuals is a dead end”. Environmental (technological, demographic, regulatory, economic, socio-cultural) changes caused by migration itself are fundamental reasons for immigrants’ engagement in entrepreneurship. Whether positively or negatively affecting IE, in general, changes in any one or more of these environmental domains are likely to influence the types of entrepreneurial activity in which immigrants engage. Therefore, scholars believe that the key difference between immigrant and native entrepreneurs is the entrepreneurial environment in which they operate (Dabi? et al., 2020). Generally, immigrants face additional obstacles to start new businesses in their new environment due to the liability of foreignness (Gur?u et al., 2020) in a dynamic environment.

With respect to the research approach, some scholars have suggested that IEEE research should focus on systematic evaluations of entrepreneurship practices and study multiple factors. They believe that systematically exploring the IEEE phenomenon through a multi-dimensional approach can produce valuable results. It has been proposed that the structural factors in different regional and cultural settings need to be addressed. IEEE researchers emphasized that the home-country settings, including political, socioeconomic and cultural factors, impact IEEE and should not be ignored in the research.

In summary, researchers have been asking for instrumental, rigorous and practical results, which stem from investigations involving a systematic and multi-factor approach that includes the effects of home- and host-countries’ ecosystems. As a new research discipline, studies on IEEE have been proven relevant to the socioeconomic chain, garnering the attention of numerous scholars worldwide, and it is enormously different from general entrepreneurship investigation. Both scientifically and empirically current studies show objectives entailing (1) attributes of immigrants from various countries; (2) effects of a venture - pursue debating the ethnic enclave were observed by analyzing immigrant’s human, social and financial capitals; (3) incentives of immigrants to create their businesses; (4) equating the entrepreneurial disparities among immigrant communities; and (5) examining the function of ethnic resources in business creation (Dabi? et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2022).

From the theory-building perspective, the most potent theories established sociologically to explain the prodigy of IEEE include the middleman minority theory (Bonacich, 1973) the enclave economy hypothesis the discrimination hypothesis (Waldinger, 1989); 4) the interactive model (Waldinger et al., 1993) the social capital argument (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993) and the notion of mixed embedment. Other researchers have conducted investigations on enterprise processing outcomes that include recognizing opportunity (Shane, 2000) cause and effect and boot scraping and inform investors and others.

More debates have arisen in regard to the methodology (which is key to any successful research) used in IEEE studies. Some researchers support the use of qualitative research methods in a constructivist/interpretivist paradigm since they believe entrepreneurs are making decisions subjectively. They also believe that effective methods for carrying out empirical studies such as case studies, phenomenology, and grounded theory explain the phenomenon of IEEE where topics are unquantifiable. Others defend the view that quantitative inquiries into IEEE are the best way to generalize the knowledge required for creating new ventures. Recently, mixed methods for studying IEEE and its phenomena have become more acceptable under a “what works better” paradigm.

All these research aims, objectives, and theories can be classified into numerous disciplines: social science, ethnic studies, human research, sociology and business management and so on. Methodologies and methods used are based on a few overarching philosophical foundations (paradigms or worldviews). These philosophical foundations will strengthen 1) scholars’ explanatory outcomes, 2) novel contributions, and 3) the trustworthiness of claims (Huff, 2009). Without a clear paradigm statement, confusion can be created when reading research texts. All researchers’ philosophical roots and assumptions, made from knowledge gained during studies, should be known to people as these assumptions form the research processes.

This paper explores the most popular theories used in IEEE study. Most commonly used theories are explained in the next section, thereby providing a list of characteristics of the theories to ease scholars’ real world practices. Finally, a review of research methodologies being used in entrepreneurship study is given to emphasize the point of research rational

Methodology

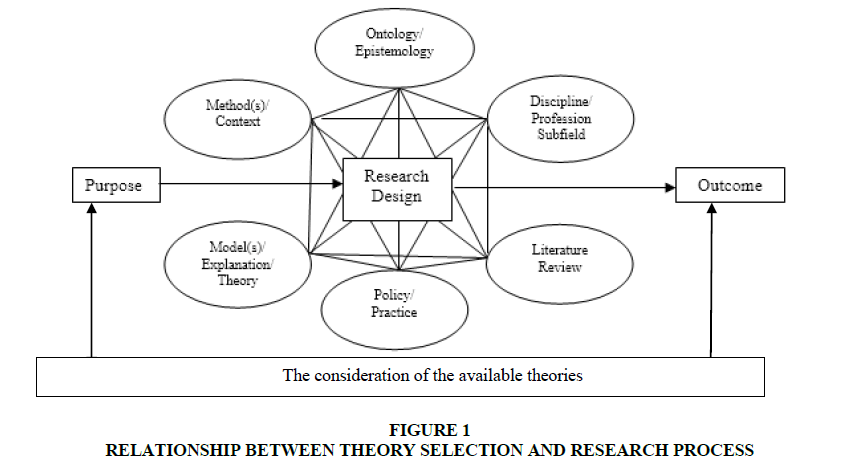

Exploring the known and unknown in a particular discipline is one of the purposes of this review research article. The subject is advanced when synthesizing research is designed to provide clear instructions for other scholars. Reviewing applicable theories in a discipline is impactful and useful when authors use the appropriate methodology and craft such articles with systematic rigor. Review studies then reconcile conflicting findings, identify research gaps and suggest exciting new directions for a given field of research, with reference to methodology, theory and contexts. This research adopted a research framework from Huff (2009), which provides an audience-focused purpose →design→outcome outline for design decisions (Top box Figure 1). This research further extended the process to include the theory selection process (Bottom box).

Theiries In IEEE Field Explained

To make changes to any of the heading tabs in the toolbar, right click on that tab and click on “modify.” This will allow you to structure the heading as you desire. Additional changes can be made by opening the “format” tab at the lower left of the “modify” box. Define “Heading 1” to be Times New Roman, 18 point, bold, all upper case, and centered on the margins (be sure not to let a first line indent command affect the centering). Choose 12 point paragraph spacing after the paragraph. You will only use the Header 1 command for the title of the article. Do NOT use the Header 1 command again anywhere in the document. Highlight the title and click on “Heading 1.”

Define “Heading 2” to be Times New Roman, 14 point, bold, initial capitals, and centered on the margins (be sure not to let a first line indent command affect the centering). Choose 12 point spacing after the paragraph. You will only use the Header 2 command for the names of the authors. Highlight the authors and their affiliations and click on “Heading 2.” Do not use titles or honorifics with the authors. That means that you will type each author’s name, followed by a comma, and that author’s affiliation. Do not include Ph.D., Dr., Professor, or other titles or honorifics. For the affiliation, type the name of the University or the name of the employer of the author.

Present the authors in the order in which they have contributed to the work, and type them one per line (do not double space between authors). When all have been typed, highlight all of the authors and affiliations at once, and click on “Heading 2.” Do NOT use Heading 2 again anywhere in the document.

Define “Heading 3” to be Times New Roman, 12 point, bold, all upper case, and centered on the margins (be sure not to let a first line indent command affect the centering). Choose 12 point spacing both before and after the paragraph. You will use the Header 3 command for ALL major headings inside your document. This will include Abstract, Introduction, etc. Just highlight the text to be used for the heading and click on “Heading 3.”

Theory of Entrepreneurship Process

Shane & Venkataraman (2000) defined entrepreneurship as the process by which “opportunities to create future goods and services are discovered, evaluated, and exploited.” In Bygrave & Zacharakis’ (2011) view, the entrepreneurship process involves all functions, activities and actions associated with identifying, pursuing, evaluating and seizing perceived opportunities and the bringing together of necessary resources for the successful formation of a new firm. Although theoretical frameworks of the entrepreneurship process differ in their assumptions and constituent variables and constructs, they do include common components such as opportunity recognition to inspire motivation, resource acquisition as one of the strategies and achievement as outcomes. This study adopted Naffziger et al. (1994); Shane et al. (2003) models in which the entrepreneurship process starts from motivations and ends with outcomes through strategies.

Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, 2001) holds that learning takes place socially and dynamically through interactions among the individual and the environment, leading to the behavior. Social context is central to the theory because it provides internal and external reinforcement of behavior. Individuals are understood to uniquely develop and sustain behavior through the influence of their environments. Their past experiences of control and reinforcement shape and explain their behaviors, since individuals self-regulate to achieve and maintain goals over time. Social cognitive theory, therefore, integrates several levels (e.g., individual, community, countries, regions) that interact and influence behaviors. SCT has been widely used in entrepreneurship research, given its emphasis on individual entrepreneurs and their environment and the increasing focus on the latter in contemporary entrepreneurship research. Notably, SCT has provided the foundations for creating entrepreneurship theory, as scholars often use the triangle framework of SCT (individual, environmental and behavioral determinants) to explain entrepreneurial behavior. In IEEE study, the researcher used SCT to create an overarching analytical framework to investigate the relationship between individual and environmental factors that impact the immigrant entrepreneur’s behavior.

Theory of Planned Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) predicts an individual's intention or motivation to engage in a behavior at a specific time and place. It was intended to explicate all behaviors over which individuals have the capability to exert self-control. The key component of TPB is behavioral intent, which is influenced by both the belief that the behavior is likely to produce the desired outcome and the subjective evaluation of the risks and benefits of that outcome. Three types of beliefs are identified: behavioral, normative and control. The theory has been used successfully to explain a wide range of entrepreneurial behaviors and motivations, such as being independent, becoming rich and utilizing personal skills (Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2015), and to develop entrepreneurial theory and conceptual frameworks (Naffziger et al., 1994; Shane et al., 2003). Behavioral outcome is understood to depend on both motivation (intention) and ability (behavioral control). The theory of planned behavior emphasizes a person's actual control over the behavior determined by attitudes, intention, subjective norms, social norms, perceived power and perceived control. In IEEE study, TPB was used to explain the IEEE process in which entrepreneurial strategies and activities (behavior) are driven by immigrant entrepreneurial motivation and intention.

Motivation Model of Entrepreneurship

Immigrant entrepreneurship studies reveal a wide range of motivations underlying the decision to start a business in a foreign land (Kourtit et al., 2015; Lan & Zhu, 2014). Entrepreneurial motivation is often loosely defined (Shane et al., 2003). Naffziger et al.’s, (1994, p.30) broad description is commonly used: “entrepreneurial motivation… describes the process by which entrepreneurs decide whether or not to engage in entrepreneurial behavior.” Shane et al. (2003), however, recommended that “researchers better define the motives that they think are important and focus on more precise measures of them.” Three entrepreneurial motivations—new venture initiation, venture growth and venture exit—apply to IE, the first being the most studied motivation. This research focused on the initial stage motivations associated with venture initiation and their precise measurement, antecedents and outcomes. To precisely measure IEEE motivations, the research conceptualized an integrated six-dimensional framework by combining two existing models: Naffziger et al.’s (1994) five-dimensional entrepreneurial process framework, comprising individual characteristics, personal environment, personal goals, idea and opportunity and business environment; and Shane et al. (2003) model, which depicts the importance of vision, knowledge, skills and capabilities as cognitive factors that shape entrepreneurship and opportunities and of environmental conditions as external actors in entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Framework

More recently, scholars have recognized the importance of employing a systems-based framework, involving the entrepreneurial environment, to support research that incorporates a comprehensive analysis of the entrepreneurial environment (Nicotra et al., 2018; Warwick, 2013), in particular by using the EE framework (Isenberg, 2011; Stam, 2015). The latter derives from the understanding that new ventures emerge and grow not only because of talented and visionary individuals but also because of the business environment in which entrepreneurs carry out their activities to achieve success.

Before the EE framework appeared as an instrument to systemically investigate and configure the entrepreneurial environment in IEEE literature, various studies had shown that IEEE is influenced by personal attributes, host-country entrepreneurial environment, co-ethnic community characteristics and immigrants’ home-country factors. Host-country influential factors identified in the literature include financial support, labor market, consumers, suppliers, professional services, social reception, regulation and political context. From the co-ethnic community perspective, community size, entrepreneurial culture, willingness to share knowledge and acceptance of low-paying jobs contribute to IEEE (Collins, 2002; Li et al., 2018; Oliveira, 2010). Home-country factors include finance, education, economic development, corruption status and government policies (Van Tubergen, 2005; You & Zhou, 2019). In this study, host- and home-country and immigrant ethnic community environments were examined together and conceptualized as the IEE.

Applied to the entrepreneurship discipline, an ecosystem refers to a system of socioeconomic, political and infrastructural domains promoting the development of innovative businesses and enhancing their performance (Stam, 2014; Stam & Spigel, 2016). Several definitions of “entrepreneurial ecosystem” have been proposed over the last two decades (Stam & Spigel, 2016; Isenberg, 2011; Brown et al., 2014; Spigel & Harrison, 2017). Although each definition incorporates different entrepreneurial factors that dynamically interact with one another, the general consensus is that a functional EE provides capital (e.g., financial, knowledge, institutional, social) to enable entrepreneurs to discover, assess, exploit and take advantage of market opportunities (Isenberg, 2011; Nicotra et al., 2018; Stam, 2015). Recent studies have expanded the elements of an ecosystem to cover additional dimensions such as culture, market, human, research institute, government and institutions (Isenberg, 2011; Motoyama & Knowlton, 2017). Each dimension is weighted differently in a specific EE. The World Economic Forum (WEF, 2013) argued that funding, workforce and market are the most critical factors to a functional EE.

The EE framework can be equally applied at city, region and national levels (Isenberg, 2011; Von Bloh et al., 2020). Isenberg (2011) often-cited article presents a national?level view of EE. However, researchers have shifted the boundary of IEEE studies from the local community or region to country or even multi-country studies (Legros et al., 2013).

Although EE has emerged as an economic development framework for creating an environment that fosters entrepreneurship, existing research on EE has been largely typological and theoretical, and its association with entrepreneurial outcomes has not yet been explored (Spigel & Harrison, 2017). Moreover, the EE framework has rarely been applied to IEEE research (Von Bloh et al., 2020). This study adopted the EE framework in each sub-project, from literature reviews and analytical framework development to empirical studies.

Theories of immigrant entrepreneurship

Numerous theories, concepts, frameworks and hypotheses have been developed and employed to explore factors that drive new immigrants to start business ventures in their host countries (Zhou, 2004). Some of these theories include the middleman minority theory (Bonacich, 1973), the discrimination hypothesis (Slamecka, 1960), the blocked mobility positions (Collins, 2002), the culture model (Kourtit et al., 2016), the enclave economy hypothesis (Portes & Jensen, 1992), the interactive model (or opportunity structure) (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990) and mixed embeddedness. They have been used effectively to explain the forces that drive IEEE in many of the advanced countries and from population ecology, anthropological, sociological and immigration perspectives (Collins, 2002).

Developed the concept of “middleman minorities” after he found some ethnic minorities were relying on their competitive advantage by occupying an intermediate position between mainstream society and their ethnic community. Blalock’s (1967) term “middleman minorities” refers not only to individual minority entrepreneurs but also to an entire entrepreneurial-oriented ethnic group. The middleman minority theory was subsequently used by Bonacich (1973) and focused on sojourners, those who do not intend to, or have not yet decided to settle permanently in their host country and therefore seek occupations with high liquidity (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990). Subsequently, scholars applied the theory to study permanent immigrants engaging in entrepreneurship (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990). The theory is still commonly used to investigate the IEEE phenomenon (Vinogradov et al., 2017). In this research, the original theorized position of the immigrant entrepreneur as a middleman, between the boundaries of mainstream society and their ethnic community, was expanded to that between their host and home countries.

Discrimination and blocked mobility hypotheses emphasize the immigrant’s reaction to environmental obstacles in a new society. After examining the association between the rate of immigrant entrepreneurship and the unemployment rate in a country, suggested that immigrants are disadvantaged in the job market because of discrimination, requiring that they start small-scale ethnic businesses to survive. These interconnected hypotheses were applied to investigate and interpret IEEE motivation in this research.

The culture model recognizes that different cultural backgrounds predispose immigrants to pursue entrepreneurship as a personal goal (Kourtit et al., 2016). The model emphasizes socio-cultural effects that pull immigrants towards engaging in entrepreneurship and was used in this study to explain why the entrepreneurship rate is higher among CCIs than most of the other ethnic groups in the IEEE literature, especially in Australia and NZ.

The enclave economy hypothesis states that immigrants start businesses that rely on their ethnic resources (e.g., in employment from customers and financial lenders) or because they lack the skills required in mainstream society (Portes & Jensen, 1989). The interactive model promoted by Aldrich and Waldinger (1990) is based on the idea that ethnic entrepreneurs adapt ethnic resources to meet the demands of mainstream opportunities. In other words, host-country opportunities are used as pull factors. The model is related to the opportunity structure notion, which emphasizes that mainstream society requires certain low-margin commercial activities that locals simply would not engage in because, for example, they involve long hours of work or too much hard work. These gaps in commercial activities provide opportunities for immigrants. Waldinger’s (1993) opportunity structure model shows that multiple interconnected factors motivate new immigrants to engage in entrepreneurship. These factors include market conditions (enclave and mainstream), access to business ownership, local employment prospects, host-country legal framework, ethnic social network and culture. The enclave economy hypothesis was used in this research to argue the position that immigrant entrepreneurs adopt enclave and mainstream strategies concurrently.

One of the often-cited theories in IEEE literature is mixed embeddedness, proposed by Kloosterman, Van Der Leun, and Rath (1999) and Kloosterman and Rath (2001). These authors postulated that IEEE activities originate from the immigrant entrepreneurs’ embeddedness in the co-ethnic community within the socioeconomic and politico-institutional environments of the host country. Mixed-embeddedness theory gives weight to the environmental drivers from the ethnic community and the host country. This theory was deployed to explain that immigrant entrepreneurs are simultaneously embedded in their host country and co-ethnic community.

Theory of Dual Embeddedness

The theory of dual embeddedness, as alternative perspectives to assimilation and integration theories, centers on the reasons and evidence for, and implications of transnational migration (Schiller et al., 1995). Described embeddedness as the extent to which an individual’s behavior depends on their networks in a specific network structure. He separated embeddedness into relational and structural aspects. Structural embeddedness emphasizes the configuration of an individual’s network of relationships, while relational embeddedness deals with the quality of those relationships. In the context of IE, transnationalism and dual embeddedness refer to immigrants who are embedded in their host and home countries and simultaneously engage in economic, political and cultural activities within the two countries.

Dual embeddedness theories postulate that economic activities occur only when the actors are embedded in the social networks and institutions of both societies (Ren & Liu, 2015). The extant literature on IEEE portrays the 21st century as a multicultural era, featuring transnationalism and dual embeddedness, whereby ethnic minorities utilize their home-country networks to access an array of valuable resources not available to their native peers in order to facilitate their transnational entrepreneurial activities (Brzozowski, 2017; Colic-Peisker & Deng, 2019). Immigrant entrepreneurs, therefore, benefit from their dual embeddedness in, and familiarity with host- and home-country socioeconomic environments. These bifocal attributes have led scholars to affirm that IEEE does have competitive advantages over host-country-focused entrepreneurship (Nkongolo-Bakenda & Chrysostome, 2020; Solano, 2015). These two theories, combined with the entrepreneurship ecosystem theory, informed the dual entrepreneurship ecosystem (DEE) framework (Duan et al., 2022) and home-country EE embeddedness theories generated in this study (Duan et al., 2021; Duan et al., 2020).

Theory of Transnationalism and Transnational Entrepreneurship

Transnationalism, first used by Bourne in 1916 in relation to migrants that maintain cultural ties with their home country, refers to the spread of economic, political and cultural processes beyond national borders. Transnational entrepreneurship in IEEE study, based on the transnationalism concept, has risen to prominence in the last twenty years. Strategic transnational entrepreneurship is "an alternative form of economic adaptation of foreign minorities in advanced societies that is based on the mobilization of their cross-country social networks” (Portes et al., 2002). The strategies executed by immigrant entrepreneurs include importing goods, exporting goods, investing in home-country business and real estate, hiring at least one home country employee and traveling abroad at least twice a year (Portes et al., 2002). Immigrants can either be pushed or pulled to engage in cross-national economic activities.

Today, the business model of transnational entrepreneurship has evolved. Information technology and digital platforms (e-commerce and social media) reduce the need for entrepreneurs to travel between host and home countries. There is also no need for transnational immigrants to employ staff or invest in real estate in their home countries. Thus, transnational entrepreneurs are simply immigrants who engage in cross-border business between host and home countries. Transnational entrepreneurship was one of the key concepts used across all the chapters in this research. Each analytical framework was based on transnational entrepreneurship and transnational entrepreneur(ship) and immigrant entrepreneur(ship) were often viewed as interchangeable.

Necessity and Opportunity For Immigrant Entrepreneurship

The necessity and opportunity IEEE model has been adapted from the entrepreneurship literature that organizes motivations for entrepreneurship into the dichotomous streams of necessity-driven (push) and opportunity-driven (pull) factors. In the necessity scenario, immigrants are pushed into entrepreneurship by obstacles that prevent them from competing in the local labor market (Chrysostome & Arcand, 2009; Reynolds, Bygrave, Autio, Cox, & Hay, 2002). Consequently, they enter less profitable and deserted business clusters and work long hours with family support to achieve business success (Chrysostome & Arcand, 2009).

Opportunity-driven IE, unlike necessity IE, is motivated by the pursuit of achievement, such as the desire for approval, personal development, independence, wealth creation and following a role model (van der Zwan et al., 2016). Typically, opportunity-driven entrepreneurs have innovative ideas, resources and market opportunities before they embark on the IEEE journey. Some scholars have identified several types of opportunity-driven immigrant entrepreneurs: traditional opportunity immigrant entrepreneurs, diaspora entrepreneurs, transnational immigrant entrepreneurs, and born global entrepreneurs (Chrysostome & Arcand, 2009). Others have continued to argue, however, that immigrants become transnational entrepreneurs because of necessity (Portes et al., 2002). Nevertheless, there is a consensus that IEEE in high-tech clusters is opportunity-driven (Hart & Acs, 2011; Lan & Zhu, 2014).

An individual’s socioeconomic status, personality and perception of the entrepreneurial environment are the critical determinants of their engagement in necessity or opportunity entrepreneurship (van der Zwan et al., 2016). Both theoretical models developed by Serviere (2010) and Chrysostome (2010) identified low levels of education and lack of language skills as obstacles to social mobility, thus leading to necessity entrepreneurship. In contrast, host-country socioeconomic conditions, job opportunities and institutional and government support are external factors that provide individuals with choices and encourage opportunity IE. In some situations, entrepreneurship is perceived as the only option for many immigrants, especially those from developing countries (Rubach et al., 2015). Immigrants who feel socially marginalized will fall back on creating opportunities through self-employment (Min & Bozorgmehr, 2000).

Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs have also been observed to differ in their growth aspirations. Opportunity entrepreneurs’ desire to grow is paramount, while necessity entrepreneurs look for low-risk and stable businesses (Chrysostome, 2010). With respect to business development strategies, necessity entrepreneurs are more likely to pursue a cost-saving strategy than an innovative strategy (Block et al., 2015). Lack of financial capital is a major barrier many necessity entrepreneurs face at the beginning of their entrepreneurial journey (Kushnirovich & Heilbrunn, 2015; Light, 1979). Chrysostome and Arcand (2009) therefore argued that it may not be appropriate to assess necessity and opportunity firm performance using the same indicators.

Push and pull is the primary theory employed to differentiate between immigrant and native-born entrepreneurs. The former are more likely to be driven by push factors, while the latter are largely pull-factor driven. The extant literature, however, presents mixed findings. Some studies have reported that the majority of immigrant entrepreneurs are necessity-driven (Bosiakoh & Tetteh, 2019), while others have signaled that opportunity entrepreneurship is the main driving force (Rametse et al., 2018). Despite the inconclusive findings, scholars have widely embraced the push-pull theory and the necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship typology (GEM, 2017/2018; Reynolds et al., 2002).

The theory of push-pull factors and related necessity and opportunity immigrant entrepreneurship were key to the investigations in this study for each sub-project, where motivations for IEEE are proposed as being associated with pull and push factors or necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs.

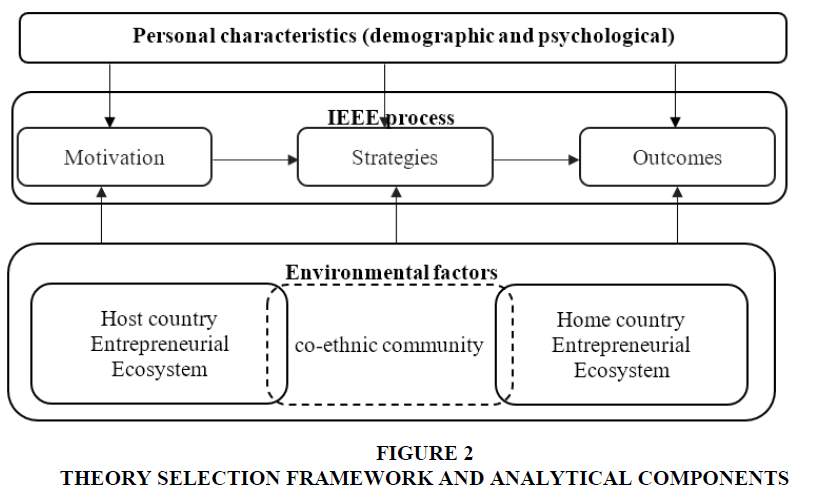

Findings

This research successfully classified the abovementioned IEEE-related theories through content analysis into two large groups: personal demographic-related notions and IEEE business environment-related positions (top and bottom boxes, Figure 2). Both group theories are driving forces for each stage of IEEE process, which includes three key components: motivation, strategy and activities, and outcomes. The research concludes that the correct theory selection needs to be based on the analytical framework and its components illustrated in Figure 2.

Given the absence of a comprehensive analytical framework of theory selection for IEEE, this study conceptualized a new framework (Figure 2) based on the abovementioned theories. Some theories such as process, motivation, transnationalism and transnational entrepreneurship, dual embeddedness and entrepreneurial ecosystem are explicitly present in the framework, while others such as push-pull, SCT and TPB are implied (but explained in detail in the chapters where they are applied). To apply this framework in the IEEE context, this study considered that the ecosystem constructs for IEEE ought to comprise both host- and home-country ecosystems since immigrant entrepreneurs operate in two business environments (Drori et al., 2009). Thus, the immigrant entrepreneurial process illustrated in Figure 2 comprises two constructs, motivations and strategies, which result in a third, outcomes.

IEEE is conceptualized as a process starting from the motivation to engage in entrepreneurship, which defines the strategies employed to achieve the desired outcomes. The dual (host and home-country) entrepreneurial ecosystem (DEE) framework (Duan et al., 2022) and its domain factors as well as personal characteristics of the entrepreneur affect each stage of the process. In other words, the motivations are determined by the DEE domain factors and personal characteristics of the entrepreneurs. Motivations in turn interact with these antecedents to determine the strategies pursued. Strategies are influenced by resources and opportunities in the DEE, the personal characteristics of the entrepreneur determine how they are deployed, and this results in outcomes. The outcomes reinforce personal characteristics of the immigrant entrepreneur as well as access to resources and opportunities in the DEE, expanding the process to generate more outcomes. The analytical framework extends Stam’s (2015, p.1765) EE framework from the host country only to the host and home countries, with IE determined by factors in the DEE. This DEE concept is supported by recent empirical studies, wherein scholars have concluded that new immigrants are embedded in dual economic, political and socio-cultural settings (Colic-Peisker & Deng, 2019; Schott, 2018). The framework depicts how embeddedness in the DEE determines the IE process and outcomes. In contrast to the region-specific EE framework, the DEE depicts the ethnic community as a subsystem that bridges the host- and home-country ecosystems. The DEE agglomerates resources from all three ecosystems to nurture entrepreneurial activities, leading to new venture creation and enhancing firm performance.

The framework also draws on the SCT and TPB theories to illustrate how personality characteristics of immigrant entrepreneurs shape their motivations, determine the strategies they adopt and the outcomes pursued. This is consistent with the generally accepted position that entrepreneurship emanates from both the individual and the environment in which they are embedded. The framework presents the central role of motivation as a process variable, which, in conjunction with the DEE factors, defines strategies pursued to achieve the desired outcomes.

Conclusion

This research conceptualized and investigated the IEEE theories and their application based on a review and content analysis focused on current available hypotheses, notions, positions and viewpoints in the research of immigrants, behavior and entrepreneurship. The study contributes to research in IEEE and to policy planning and implementation. Importantly, immigrants make up a significant proportion of entrepreneurs in their host countries and help expand international trade, thereby improving the balance of trade in these countries. Immigrant entrepreneurs have the potential to not only create economic value but also establish productive social and cultural connections between immigrants and their host societies. The socio-cultural diversity created through multiculturalism encourages new ideas and innovations that benefit the host countries.

The research concludes that the theory selection should consider the stages of IEEE. The findings from the analyses of the environmental effects on the IEEE process variables of motivation and business strategies and also on business outcomes, provide evidence that policy makers need to understand how immigrants experience the entrepreneurial terrain in their new country in order to formulate appropriate policies to advance the sector. This research identifies common as well as unique entrepreneurship ecosystem domains and associated elements that must be considered if policy makers are to encourage IEEE and enhance their contributions to the economy. The findings highlight the importance of improving ecosystem embeddedness and engagement for new immigrants, as they constitute new and resourceful contributors to the future economic and social development of both their host and home countries.

The finding revealed that theory selection should consider entrepreneurs’ individual sircumstances. The research uncovers how theories connect immigrants’ host countries, home countries and communities and how barriers such as the liability of foreignness and discrimination push them into necessity entrepreneurship, where they struggle to survive. The economic value derived from necessity immigrant entrepreneurs is in unambiguous contrast to that of immigrants who pursue opportunity-driven behaviours within the host and home countries, thus transferring innovations to enhance economic outcomes in the two contexts. These opportunity-driven entrepreneurs have the potential to further prosperity by reaching into several other foreign markets. Immigrant entrepreneurs actively pursue a better life and business opportunities in the host country, so a more socially inclusive system would be beneficial for localizing and/or internationalizing immigrants' entrepreneurial and business activities.

Furthermore, the research identifies the importance of business environment-related theories, which suggests to host-country governments that they should design and promote incentive programs to foster and reward enterprising individuals and outstanding immigrant firms.

Finally, the research contributes to the IEEE and entrepreneurship literature. It drew on key theories and models to create a new integrated conceptual framework of DEE for theory selection. It also recommends to apply the concept of the immigrant entrepreneurial ecosystem to engage IEEE research theory selection and application. It depicts an entrepreneurship process triggered by events in the host- and home-country environments. These combine with the personal characteristics of the immigrant to create the motivation to pursue entrepreneurship. Motivations, which could be necessity- or opportunity-driven, determine the strategic activities pursued and the outcomes achieved in terms of firm performance. The results, therefore, contribute empirical evidence to the IEEE field in terms of the relationships among host- and home-country ecosystems and personal characteristics of immigrants, as antecedents, and the process variables of (necessity/opportunity) motivation and strategies adopted. The findings present the relationships among these antecedents and process variables on one end and the financial and non-financial outcomes of the IEEE process on the other. The findings also reveal direct and mediated effects theory selection.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Aldrich, H. (1990). Using an ecological perspective to study organisational founding rates. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 14(3), 7-24.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alvedalen, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: towards a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 887-903.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. (2020). Migration, Australia.

Baker, T., & Nelson, R.E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329-366.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baker, T., Powell, E.E., & Fultz, A.E. (2017). Whatddya Know?: Qualitative Methods in Entrepreneurship. In The Routledge companion to qualitative research in organization studies (pp. 248-262). Routledge.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 1-26.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baycan, T., Sahin, M., & Nijkamp, P. (2012). The urban growth potential of second-generation migrant entrepreneurs: A sectoral study on Amsterdam. International Business Review, 21(6), 971-986.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Blalock, H.M. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations (Vol. 325). New York: Wiley..

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Block, J.H., Kohn, K., Miller, D., & Ullrich, K. (2015). Necessity entrepreneurship and competitive strategy. Small Business Economics, 44(1), 37-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bonacich, E. (1973). A Theory of Middleman Minorities. American Sociological Review, 38(5), 583-594.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bosiakoh, A.T., & Tetteh, W.V. (2019). Nigerian immigrant women’s entrepreneurial embeddedness in Ghana, West Africa. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 38-57.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brown, R., Mawson, S., Lee, N., & Peterson, L. (2019). Start-up factories, transnational entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial ecosystems: unpacking the lure of start-up accelerator programmes. European Planning Studies, 27(5), 885-904.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brzozowski, J. (2017). Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Economic Adaptation: A Critical Analysis. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 5(2), 159-176.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bygrave, W. & Zacharakis, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship (2nd ed). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cavaye, A. L. (1996). Case study research: a multi?faceted research approach for IS. Information systems journal, 6(3), 227-242.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chrysostome, E. (2010). The success factors of necessity immigrant entrepreneurs: In search of a model. Thunderbird International Business Review, 52(2), 137-152.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chrysostome, E., & Arcand, S. (2009). Survival of Necessity Immigrant Entrepreneurs:: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Comparative International Management, 12(2), 3-29..

Colic-Peisker, V., & Deng, L. (2019). Chinese business migrants in Australia: Middle-class transnationalism and ‘dual embeddedness’. Journal of Sociology, 55(2), 234-251.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Collins, F.L. (2012). Transnational mobilities and urban spatialities: Notes from the Asia-Pacific. Progress in Human Geography, 36(3), 316-335.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Collins, J. (2002). Chinese entrepreneurs: the Chinese diaspora in Australia. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 8(1/2), 113-13.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Collins, J., & Low, A. (2010). Asian female immigrant entrepreneurs in small and medium-sized businesses in Australia. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(1), 97-111.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Council, A. I. (2016). The economic impact of migration. The Migrant Council of Australia Report.

Dabic, M., Vlacic, B., Paul, J., Dana, L.P., Sahasranamam, S., & Glinka, B. (2020). Immigrant entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda . Journal of Business Research, 113, 25-38.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dai, F., Wang, K.Y., & Teo, S.T. (2011). Chinese immigrants in network marketing business in Western host country context. International Business Review, 20(6), 659-669.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dheer, R.J. (2018). Entrepreneurship by immigrants: a review of existing literature and directions for future research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(3), 555-614..

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational Entrepreneurship: An Emergent Field of Study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001-1022.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Duan, C., & Sandhu, K. (2021). Immigrant entrepreneurship motivation–scientific production, field development, thematic antecedents, measurement elements and research agenda. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Duan, C., Kotey, B., & Sandhu, K. (2020). Transnational immigrant entrepreneurship: effects of home-country entrepreneurial ecosystem factors. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(3), 711-729.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Duan, C., Kotey, B., & Sandhu, K. (2021). Understanding immigrant entrepreneurship: home-country entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 24(1), 2020.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Duan, C., Kotey, B., & Sandhu, K. (2022). Towards an Analytical Framework of Dual Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Research Agenda for Transnational Immigrant Entrepreneurship. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 23(2), 473-497.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Duan, C., Kotey, B., & Sandhu, K. (2021b). E-commerce Digital Platforms and Transnational Immigration Entrepreneurship. Journal of Global Information Management, scheduled in 30(3).

Duan, C., Kotey, B., & Sandhu, K. (2021). A systematic literature review of determinants of immigrant entrepreneurship motivations. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 1-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research: Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gartner, W.B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 696-706.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

GEM. (2012). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

GEM. (2017/2018). GEM Global Report 2017/18.

Gomez, C., Perera, B.Y., Weisinger, J.Y., Tobey, D.H., & Zinsmeister-Teeters, T. (2015). The Impact of Immigrant Entrepreneurs' Social Capital Related Motivations. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 18(2), 19-30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gur au, C., Dana, L.P., & Light, I. (2020). Overcoming the Liability of Foreignness: A Typology and Model of Immigrant Entrepreneurs. European management review, 17(3), 701-717.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hart, D.M., & Acs, Z.J. (2011). High-Tech Immigrant Entrepreneurship in the United States. Economic Development Quarterly, 25(2), 116-129.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hart, M., Bnner, K., Levie, J., & Heery, L. (2018). GEM UK 2017 report: enterprising immigrants boosting prosperity in the UK.

Hohenthal, J. (2006). Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods in research on international entrepreneurship. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 4(4), 175-190.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Huff, A. S. (2008). Designing research for publication. Sage.

International Organization for Migration [IOM]. (2020). World migration report 2020.

Isenberg, D. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: Principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. Presentation at the Institute of International and European Affairs, 1(781), 1-13.

Khosa, R.M., & Kalitanyi, V. (2015). Migration reasons, traits and entrepreneurial motivation of African immigrant entrepreneurs. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 9(2), 132-155.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kourtit, K., Nijkamp, P., & Arribas-Bel, D. (2015). Migrant Entrepreneurs as Urban 'Health Angels' - Contrasts in Growth Strategies. International Planning Studies, 20(1-2), 71-86.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kushnirovich, N. (2015). Economic Integration of Immigrant Entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 3(3), 9-27.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lan, T., & Zhu, S.J. (2014). Chinese apparel value chains in Europe: low-end fast fashion, regionalisation, and transnational entrepreneurship in Prato, Italy. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 55(2), 156-174.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Laughlin, R. (1995). Empirical research in accounting: alternative approaches and a case for “middle?range” thinking. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(1), 63-87.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Le, A.T. (2000). The determinants of immigrant self-employment in Australia. International Migration Review, 34(1), 183-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Legros, M., Karuranga, E.G., Lebouc, M.F., & Mohiuddin, M. (2013). Ethnic entrepreneurship in OECD countries: A systematic review of performance determinants of ethnic ventures. International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER), 12(10), 1199-1216.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lin, D., Zheng, W., Lu, J., Liu, X., & Wright, M. (2019). Forgotten or not? Home country embeddedness and returnee entrepreneurship. Journal of World Business, 54(1), 1-13.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mel, D. (1999). Life's A Pitch: Launching A Valley Internet Start-Up.(Industry Trend or Event). Inter@ctive Week, Nov, 1999.

Min, P.G., & Bozorgmehr, M. (2000). Immigrant entrepreneurship and business patterns: A comparison of Koreans and Iranians in Los Angeles. The International Migration Review, 34(3), 707-738.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Naffziger, D.W., Hornsby, J.S., & Kuratko, D.F. (1994). A proposed research model of entrepreneurial motivation. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 18(3), 29-42.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ngota, B.L., Rajkaran, S., Balkaran, S., & Mangunyi, E.E. (2017). Exploring the African immigrant entrepreneurship-job creation nexus: A South African case study. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(3), 143-149.

Nicotra, M., Romano, M., Del Giudice, M., & Schillaci, C.E. (2018). The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: A measurement framework. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(3), 640-673.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nkongolo-Bakenda, J.M., & Chrysostome, E.V. (2020). Exploring the organizing and strategic factors of diasporic transnational entrepreneurs in Canada: An empirical study. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 18(3), 336-372.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Portes, A., & Jensen, L. (1992). Disproving the enclave hypothesis: Reply. American Sociological Review, 57(3), 418-420.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Portes, A., Guarnizo, L.E., & Haller, W.J. (2002). Transnational entrepreneurs: An alternative form of immigrant economic adaptation. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 278-298.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ren, N., & Liu, H. (2015). Traversing between transnationalism and integration: Dual embeddedness of new Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs in Singapore. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 24(3), 298-326.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reynolds, D.P., Bygrave, D.W., Autio, E., Cox, W.L., & Hay, M. (2002). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2002 Executive Report.

Rosique-Blasco, M., Madrid-Guijarro, A., & Garcia-Perez-de-Lema, D. (2017). Performance determinants in immigrant entrepreneurship: An empirical study. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 15(4), 489-518.

Rubach, M.J., Bradley III, D., & Kluck, N. (2015). Necessity entrepreneurship: a Latin American study. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 19, 126..

Schiller, N.G., Basch, L., & Blanc, C.S. (1995). From immigrant to transmigrant: Theorizing transnational migration. Anthropological quarterly, 68(1), 48-63.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schott, T. (2018). Entrepreneurial pursuits in the Caribbean diaspora: networks and their mixed effects. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 30(9-10), 1069-1090.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sequeira, J., Mueller, S.L., & McGee, J.E. (2007). The influence of social ties and self-efficacy in forming entrepreneurial intentions and motivating nascent behavior. Journal of developmental entrepreneurship, 12(03), 275-293..

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shane, S., Locke, E.A., & Collins, C.J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human resource management review, 13(2), 257-279.

Slamecka, N.J. (1960). Tests of the Discrimination Hypothesis. The Journal of General Psychology, 63(1), 63-68.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Solano, G. (2015). Transnational vs. domestic immigrant entrepreneurs: a comparative literature analysis of the use of personal skills and social networks. American Journal of Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 1-20.

Spigel, B., & Harrison, R. (2018). Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 151-168.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stam, E. (2014). The dutch entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems.

Stats NZ (2018). 2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights.

Sui, S., Morgan, H.M., & Baum, M. (2015). Internationalisation of immigrant-owned SMEs: The role of language. Journal of World Business, 50(4), 804-814.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ullah, F., Rahman, M.Z., Smith, R., & Beloucif, A. (2016). What influences ethnic entrepreneurs' decision to start-up. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(4), 1081-1103.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

UN. (2017). International migration report.

UN. (2019).International migrant stock 2019.

UNCTAD. (2018). Policy guide on entrepreneurship for migrants and refugees.

UNE (2021). Higher degree research thesis by publication guideline. University of New England.

van der Zwan, P., Thurik, R., Verheul, I., & Hessels, J. (2016). Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Business Review, 6(3), 273-295.

Van Tubergen, F. (2005). Self-employment of immigrants: A cross-national study of 17 western societies. Social Forces, 84(2), 709-732.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vinogradov, E., Jorgensen, E.J., & Benedikte. (2017). Differences in international opportunity identification between native and immigrant entrepreneurs. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 15(2), 207-228.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Von Bloh, J., Mandakovic, V., Apablaza, M., Amoros, J.E., & Sternberg, R. (2020). Transnational entrepreneurs: opportunity or necessity driven? Empirical evidence from two dynamic economies from Latin America and Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(10), 18.

Waldinger, R. (1993). The ethnic enclave debate revisited. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 17(3).

Warwick, K. (2013). Beyond industrial policy: emerging issues and new trends.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

WEF. (2013). Entrepreneurial ecosystems around the globe and company growth dynamics.

Yasuyuki, M., & Karren, K. (2017). Examining the Connections within the Startup Ecosystem: A Case Study of St. Louis. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 7(1).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yin, R.K. (2002). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 5.

You, T.L., & Zhou, M. (2019). Simultaneous embeddedness in immigrant entrepreneurship: global forces behind chinese-owned nail salons in New york city. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(2), 166-185. doi:10.1177/0002764218793684

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhou, M. (2004). Revisiting ethnic entrepreneurship: Convergencies, controversies, and conceptual advancements. International Migration Review, 38(3), 1040-1074.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zolin, R., Chang, A., Yang, X.H., & Ho, E.Y.H. (2016). Social capital or ethnic enclave location? A multilevel explanation of immigrant business growth. Thunderbird International Business Review, 58(5), 453-463.

Received: 06-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12640; Editor assigned: 07-Dec-2022, PreQC No. AEJ-22-12640(PQ); Reviewed: 20- Dec-2022, QC No. AEJ-22-12640; Revised: 25-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12640(R); Published: 27-Dec-2022