Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 1

Understanding The Various Ways Entrepreneurship Education in Country of Origin Influences Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation in the Host Country

Kingsley Njoku, Technological University Dublin

Citation Information: Njoku, K. (2023). Understanding The Various Ways Entrepreneurship Education In Country of Origin Influences Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation In The Host Country. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 26(1),1-18.

Abstract

Entrepreneurship Education (EE) provides students with basic tools and ideologies necessary for taking informed decisions regarding entrepreneurial activities (EAs) and business formation opportunities. In Njoku & Cooney (2020), the term ‘education’ was contextualized as an ethnic variable factor, capable of influencing an ethnic group’s Opportunity Formation (OF) idiosyncrasies subject to their countries of origin. As a cultural variable, what is not yet known in the literature is how EE might influence EAs amongst Immigrant Entrepreneurs (IEs). This paper will demonstrate that participants’ inclination to self-employment is facilitated by entrepreneurial courses undertaken before their arrival to the host country. In congruence with prior studies, immigrants’ EAs are influenced by mixed relationship. Therefore, the author argues that immigrants’ home countries play significant roles and thus facilitates EE subject to embedded predisposing skills, which immigrants bring to entrepreneurship. EE shapes immigrants’ entrepreneurial behaviours by influencing their cognitive abilities, which directs their choice of career path. Using data collected from 20 IEs in Dublin, this paper will make contribution to knowledge by building a framework model, that will show how education as a ‘cultural variable’ plays the role of ‘enabler’ amongst participants. Thus, the aim of this paper is to show how cultural perceptions can be subjective based on the responses obtained from participants. Using a phenomenological qualitative methodology, the paper analyses participants’ entrepreneurial behaviours based on their responses during in-depth interviews. Consequently, understanding how participants interpreted ‘educational culture’ is vital to elucidating how their perceptions influence their entrepreneurial (OF) as either ‘enablers’ of ‘threats’.

Introduction

Wielemans & Chan (1992) shows that the view of ‘education’ as purely an ‘economicbenefit’ term can result to the loss of its profound meaning, because it implies that those undergoing different levels of training are only but commodities to be manufactured. To ensure that what students learn will enable them to make macro-projections and plan in order to reduce the gap between unemployment and lack of jobs in the job market, ‘education time’ should not be calculated only in terms of invested-process-product-time. As an embodiment of cultural components, the need to revisit the concept of ‘Entrepreneurship Education’ (EE) based on different ways it influences the student is necessary for better understanding and as well, for the growth of entrepreneurship.

From an immigrant entrepreneurial point of view, the impact of EE on Entrepreneurial Activities (EAs) and outcomes remains a novel area of investigation (Kuratko, 2005; Matlay, 2006; Rasmussen & Sørheim, 2006; Solomon & Matlay, 2008). Needless to say, there is yet to emerge an empirical paper investigating EE as a cultural variance with focus on how it might have influenced Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation (EOF) amongst immigrant ethnic groups. As the gap identified in the literature, this paper will address it using data collected from 20 Immigrant Entrepreneurs (IEs) from 4 different ethnicities, who reside and run their businesses in Dublin. Immigrants’ contribution to the host economies has attracted the attention of many governments and private organisations (Lemes et al., 2010). As a sure keyway to success, governments have considered supporting both immigrant and native entrepreneurs.

Based on participants’ experiences, the objective is to develop a model framework that will explore EE from a cultural perspective to show how participants’ business formation idiosyncrasies are influenced differently in the host country. Using phenomenological qualitative method, in-depth data was collected from 4 ethnic groups through semi-structured interview. The results were interpreted using interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) technique. Findings were juxtaposed across other ethnicities. These highlighted the difference between the roles played by other explanatory variable factors.

Entrepreneurship Education

Study shows that the concepts of ‘education’ and ‘culture’ have been examined differently (Kuratko, 2005; Matlay, 2006; Rasmussen & Sørheim, 2006; Solomon & Matlay, 2008). The idea is to objectively demonstrate in context the different ways in which individual cognitive ability can be expressed based on their interpretations of what constitutes ‘reality’ as informed by experience. The importance of examining the impacts of ‘education’ from a cultural point of view is paramount to identify how entrepreneurship education (EE) fits into a broad theoretical framework for understanding entrepreneurial behaviour in education (Hallinger & Leithwood, 1996). In this context, the question that has risen is weather societal ‘culture’ construct be classified under exogenous or endogenous variable factors influencing entrepreneurial activities (EAs)? Regardless, the literature shows that an individual interpretation of what constitutes ‘reality’ subject to a particular phenomenon should be respected since it is based on experience and perception of the event (Alvarez et al., 2013).

From a cultural perspective, the concept of ‘EE’ had been established as an embodiment of cultural values comprising of embedded customary components since it shapes the way people reason and approach their daily realities (Njoku & Cooney, 2020). Thus, the question of how societal ‘culture’ construct should be classified was addressed in Njoku & Cooney (2020). This showed that participants’ interpretations of their experiences should be viewed as true representations of their reality to uphold research ethics and integrity, thus reduce bias. Examined under the same rubric as economic and political culture following their embeddedness in the system, ‘EE’ influences not only the willpower to career choices, but also provides options between following the traditional career path and becoming self-employed.

Prior research studies have examined ‘culture’ based on the role it plays in the context of EE (Hallinger & Leithwood, 1996). For instance, the seminal works of Getzels et al., (1968) identified both the administrator and the educational institution in a cultural context. This further highlights the importance of context (McKeever et al., 2014; Welter, 2011). Context in this perspective helps with understanding specifics, especially in research based on specialization of interest. Hence, ‘education’ as a cultural component brings out the varying impact that different cultural values could exert on the thinking and behaviour of people subject to their ethnic origins. The notion of context thus focuses attention on differences in the way the educational system as a cultural variable influences entrepreneurial behaviours through indoctrination and transferring entrepreneurial values.

From a relational point of view, the relationship between ‘education’ and ‘culture can be examined from an interdependent hypothetical scenario. This reasoning posits that if cultural variables are subjective Njoku & Cooney (2018), the concept of EE can be argued based on the same rubric. Since ‘education’ as a process indoctrinates others through learning, it also transfers ideas and values through imposition, which shapes behaviours and get students to act in accordance with stipulated institutional regulations. This had been established to influence the way people reason and act in response to daily phenomena subject to knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation. As an embedded component, entrepreneurial behaviours are influenced subject to genetic heritages (Kennedy, 2018). This is evident in children who clone their parents’ career paths.

Where culture can be vaguely defined as a practice that has been commonly recognised as an aspect of life within a group, it suffices to state that EE is culture-centric and thus, an important aspect of life since it shapes behaviours and actions in conformity with social norms. For a deeper understanding of how ‘EE’ relates with ‘culture’, the works of Peters (2001) is of great importance. Under Margaret Thatcher’s administration, the notion of ‘enterprise culture’ emerged as a central motif in political thought in the UK (Peters, 2001). Though represent a profound shift away from the Keynesian welfare state to a deliberate attempt at cultural restructuring, the shift took the form of the ‘enterprise education’ in education. This is important in the context of EE and culture because it sets the context under which both can be explore by highlighting that the rise in EE from a cultural point of view in Thatcher’s years.

As Peters (2001) acknowledged “Education has come to symbolise an optimistic future based on the increasing importance of science and technology as the engine of economic growth and the means by which countries can successfully compete in the global economy in years to come”. An understanding of the relationship between ‘culture’ and ‘EE’ would require the remodelling of the educational system to embody cultural perspectives since the influence of educational culture to Opportunity Formation (OF) can be traced back to the time of Margaret Thatcher, where it was established that culture and enterprise exist in a co-dependence relationship (Peters, 2001). Given that governments have deemed such relationship important to sustain economic growth, EE operates in a co-dependent relationship with culture. The argument is that since ‘education’ shapes entrepreneurs’ cognitive skills through indoctrination and imposition, it also provides them with ideological perceptions that have been embedded into the society and recognised as part of existence within the institutional system.

Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation

In recent times, businesses established by immigrants in their host countries have been observed to grow rapidly across western societies. Evansluong (2016) agrees that immigrant Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation (EOF) has become a matter of international interest. Based on the review of the literature, the pursuit of entrepreneurial action requires strong cognitive skills. As Vinogradov & Elam (2010) show, immigrant entrepreneurs (IEs) have gained significant attention over the past three decades, hence there is a growing need for understanding how immigrants view and perceive the practice of EOF in their country of residence. Consequently, the need to employ the logic of the visual mixed embeddedness framework (VMEF) is paramount to clearly understand the phenomenon of immigrant EOF (Njoku & Cooney, 2018).

Due to restricted mobility in the labour force, IEs’ inability to access existing jobs has led to their engaging in EAs, thus utilizing existing enterprise skills to achieve their goals in their country of residence (Hastie, 2001). Within this context, Halkias & Adendorff (2016) have identified that ethnic variables in the form of cultural factors/components (amongst many others) have played important roles in the way that IEs engage in pursuing, running and managing EOF. In business models of entrepreneurial activity, it was proposed that an entrepreneur’s ability to reduce uncertainties that prevent them from taking action to create new opportunities is facilitated by his/her beliefs (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006). Furthermore, despite the imprecise definitions over EOF models, the review of the literature shows that there are several models on how entrepreneurs form opportunity (Burkhart et al., 2011; Zott et al., 2011). In Ojala (2016, p.3), the conceptualization of a business model comprises of four different components (i.e., the product/service, the value network, value delivery and the revenue model). Thus, a business model is defined as: “a description of the value a company offers to one or several segments of customers and of the architecture of the firm and its network of partners for creating, marketing and delivering this value and relationship capital, to generate profitable and sustainable revenue streams” (Osterwalder et al., 2005). Given that the propensity to start and run businesses is higher amongst immigrants than natives, it has been argued that understanding how immigrants view EOF is paramount. Thus, immigrants adopt an approach different from native entrepreneurs based on their perceptions of phenomenal process (Njoku & Cooney, 2018).

Consequently, Axman (2003) shows that entrepreneurship opportunities are hard to define because of the different ways it has been perceived and the processes involved in creating and forming new businesses opportunities. Entrepreneurial opportunity occurs when a niche product/service with a competitive advantage and reasonable chance to succeed in the market has been identified either by a person or an enterprise (Longenecker, 2009). It had further been argued that a complete definitional paradigm for EOF must comprise of all the components suggested in (Ojala, 2016). Such as identifying a market niche (product/service) with a competitive advantage and high potential to succeed. Since entrepreneurial actions determine the critical pathways to the creation and development of sustainable business models Breat (2009), the authors argue that EOF occurs when viable ideas with potential economic values that are capable of solving both consumer, market and environmental related needs are identified and implemented.

Although, the adopted definitional approach was influenced by the Schumpeterian logic that constant change in consumer behaviour affects EOF (Schumpeter, 1934), the reviewed literature acknowledges that there is a lack of a unified definition for EOF (Low & MacMillan, 1988).

Table 1 captures the works of previous entrepreneurial theorists who pioneered the basis for understanding EE and how it informs EOF decision making through its embeddedness with cultural values as IEs have repeatedly demonstrated. It further highlights the principal EOF processes and how they facilitate the formation of sustainable businesses by entrepreneurs. Table 1 further demonstrates how underpinning theories and their adaptabilities have been explored differently to achieve similar results during OF process. From an immigrant entrepreneur’s perspective, the table identified relationship and points out the different positions of scholarly ontological and epistemological perceptions regarding EOF, focusing on the roles played by EE in the country of origin. Hence to every individual entrepreneur, it can be argued that what constitutes ‘reality’ is subject to experience, because it originates from within, as informed by his/her perceptions of them and thus described as embedded enabling factors. Since ‘reality’ is a product of experience subject to a particular phenomenon, how it is interpreted is informed by how it was perceived. Therefore, their interpretations are bound to differ between individuals.

| Table 1 Key Advocates Of Entrepreneurship Education & Opportunity Formation Process Models |

||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Authors | EOF Models & Theories/Entrepreneurship Education |

| The direction of entrepreneurial process. |

Shane (2003) | A step-by-step process of EOF beginning with the theory of existence of opportunity to performance. |

| Creative & Discovery Spectrum | Breat (2009) | A strategy on how entrepreneurs bring EOF process to existence through actions. |

| The role of the pattern recognition in opportunity recognition | Baron (2006) | A process of EOF through recognition by alert entrepreneurs. |

| The Moore-Bygrave Model of Entrepreneurial Process | Moore (1986); Bygrave (2004) | How entrepreneurs achieve EOF through a stage event approach. |

| A dynamic entrepreneurial Process model |

Timmons (1990) | A model on how EOF process is achieved through identifying 3 important components. |

| The basic structure of entrepreneurial process model | Grebel et al. (2001, 2003) | A seven level strategy to an EOF process model and where it primarily begins. |

| Ideas assessment & business development process | Hofstrand, D (2006) | A step-by-step approach on how EOF process is assessed prior to development. |

| Bottom-Up & Top-Down processes of Opportunity belief formation | Shepherd et al. (2007) | This is a coherent theory on how belief formation facilitates EOF process in practice. |

| The effectuation process | Sarasvathy, 2001) | The effectuation logic strategy to EOF through fabrication of the mundane realities rather than resorting to discovery and exploitation of existing opportunities. |

| A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation | Bhave (1994) | An EOF process through the stimulation of both internal and external resources within an entrepreneur's environments. |

| Entrepreneurial discovery & the competitive market process: An Austrian approach. | Kirzner (1997) | An integrative model for EOF based on the works of Mises and Hayek (Austrian Economists). |

| Education & Culture in Industrialized Asia | Wielemans & Chan (1992) | Studia Paedagogica |

| Entrepreneurship Education | Manimala & Thomas (2017) | Experiments with Curriculum, Pedagogy and Target groups |

| Entrepreneurship Education | McElwee (2017) | New Perspectives on Entrepreneurship Education |

| Entrepreneurship Education | Kent, (1990) | Current Developments & Future Directions |

| Handbook of Research in Entrepreneurship Education | Fayolle (2007) | A General perspective (Vol. 1) |

| Illuminating the Black Box of Entrepreneurship Education Programs | Maritz & Brown (2013) | Education Plus Training |

Although studies have been conducted on business models and entrepreneurial opportunities to highlight how entrepreneurs utilize good business strategies during new business opportunity formation Breat (2009), the literature equally acknowledges that before the actors in the context can transform resources into products of economic goodwill and value, they first have a visual imagery of the business ideas with a strong conviction that their implementation will be of economic benefit (Njoku & Cooney, 2018). Since immigrants’ home countries serve as sources of opportunities, logic dictates that the predisposing skills they bring to entrepreneurship are inherently facilitated by prior entrepreneurial trainings received in their country of origins (e.g. education and family training). Thus, an entrepreneur is an actor who manifests what is in his/her mind in the form of transforming raw materials from perception into reality (Cherukara & Manalel, 2011). This distinguishes between business opportunities amongst immigrant and native entrepreneurs (Ram et al., 2000).

During the process of new business formation, immigrants’ families and country of origin are instrumental in understanding the concept of EE as an ‘enabler’ and, thus offers vital information which continually helps to develop diverse societies (De Vries, 2007). Hence, cultural factors have equally been identified to play an important role in the way that immigrant entrepreneurs form business opportunities (Halkias & Adendorff, 2016). Given that different reasons underpin the decision to be self-employed, IEs view EOF differently comparable to native entrepreneurs (ibid). Based on Evansluong (2016), the study of EE in line with immigrants’ opportunity creation process models is imperative because businesses and opportunities created by immigrants are yet to earn sufficient attention in entrepreneurship research (Aliaga-Isla & Rialp, 2013).

In answering the question on whether IEs use the same models/strategies as the mainstream entrepreneurs or follow a different approach Brush et al. (2010; Bygrave (2004), it is important to establish that the type of business that an immigrant entrepreneur starts, how it operates and its success is shaped by the opportunity structure of the community, group’s characteristics, region and the country of his/her residence (Halkias & Adendorrff, 2016). Evansluong (2016) refers to these factors as the “embedding process” because immigrant entrepreneurial models consider enabling factors and threats from both countries when creating new business opportunities. Evansluong (2016) further points out that “the entrepreneurial opportunities of immigrant entrepreneurs must be examined (a) in a process manner and (b) in relation to immigrant entrepreneurs’ actions in the home country and the host country because their business activities are influenced by both countries”. Thus, immigrant entrepreneurial opportunity formation process model involves certain factors uniquely identifiable in their activities that come in the forms of previous latent entrepreneurial trainings, networking and government regulations in their country of residence (Bolivar-Cruzet et al., 2014). In order to identify the nature of influence EE has on immigrant entrepreneurial behaviour as an explanatory variable ‘enabling factor’ from the home country, its role within the context of EOF must first be examined to show how these relate. Also, their simultaneous interactions with both internal and external resources present in both countries must be considered.

While research studies by Kuratko (2005), Matlay (2006), Rasmussen & Sørheim (2006), Solomon & Matlay (2008) shade important light regarding EE, Evansluong (2016), Singh et al., (2013); Bhave (1994) provide basis for exploring and understanding the topic in discussion from an immigrant entrepreneurs’ point of view based on the typology in Cyert & March (1963) on how opportunities can be recognised and exploited subject to stimulated ‘internal’ and ‘external’ factors. In congruence with Singh et al. (2013) on black entrepreneurship in the USA, it is evident that EE and business activities cannot be separated Evansluong (2016) because together they induce entrepreneurial action. As immigrants have shown, EOF process is influenced by factors from their country of origin (e.g. EE. Training, etc.) And enablers present in the host country (government regulation, institutions, etc.). Immigrant entrepreneurial creations are integrative, holistic and sustainable Timmons (1990) and are different from the mainstream entrepreneurial approach.

Research Methodology

To show how EE (as explanatory variable factor) in the country of origin influences immigrants’ approach in forming new business opportunities in their county of residence, an exploratory study was undertaken with participants from diversified ethnic backgrounds (i.e. Nigeria, Poland, Brazil and Pakistan). As a cultural variable, to expound how EE might have affected the perceptions of the subjects, participants were selected from a mixed background. The aim is to identify how the cultural differences in their backgrounds reflected in their understanding of entrepreneurial behaviour based on their actions. Saunders et al. (2016) agree that a mixed perception on what constitutes one’s ‘reality’ based on his/her experience makes a good qualitative study.

A flexible methodological approach was exercised in the current research and justified by (Smith et al., 2009). The authors recommended that novice phenomenological analysts should be innovative in their methodological approaches. In conjunction with analysing societal determinants that occurred, the author employed a phenomenological qualitative research methodology analysis to examine values and population principles. Using equal sample sizes and parallel questions, data was collected from 20 IEs from Nigeria, Poland, Brazil and Pakistan (5 participants from each country), using in-depth interview technique. These communities were selected because they provide the largest groups of IEs in Ireland (CSO, 2018).

The interview process lasted over 3 months and was conducted at nineteen different sites (e.g. at participants’ residence, workplace, etc.) (Marshall & Rossman, 2016). The rationale for employing a qualitative method was based on its flexible designs. While the primary aim of this study was to engage participants in a face-to-face in-depth conversation to understand the essence of their lived experiences, the concern is that a qualitative method is unable to generalize data from smaller to a larger group. This was mitigated by exploiting the flexibility offered by the qualitative method (i.e. it gives room for alteration and possible modification of any design component during the study to accommodate new developments). This provides stronger reasons for using a phenomenological approach and overrides any limitation likely to arise. Hence, a clearer understanding of the study problem was achieved through in-depth inquiry using abductive reasoning technique. A phenomenological approach aided and offered suggestions regarding how to resolve issues that were discovered. Table 2 below summarises the methodological choice as underpinned by theoretical justifications.

Table 2 details the adopted processes considered during data analysis (i.e. the different phases taken in their order of appearance). Also, Table 2 captures the empirical authorities underpinning their theoretical adoptions and justifications. To substantiate the grounds for the use of a phenomenological approach in this study, the author further highlights the rationale for each decision taken. According to Smith et al. (2009), the phases in qualitative methods attempt to resolve questions accompanying each phase. The results obtained were influenced by the current research stances (e.g. approach to reality (ontology), perceptions of reality (epistemology), the value-stance (axiology) and the procedures used in the study (methodology) (Creswell & Poth, 2017).

| Table 2 Overview Of Choice Of Methodology & Justifications |

||

|---|---|---|

| Choices Made | Justifications | |

| Method | Qualitative Method (QUAL M) (Creswell & Poth, 2017) | Qualities method is the appropriate approach because it explores lived experience) (Abebrese, 2013) of people. |

| Approach to Theory Development | Abductive (Saunders et al., 2016) | The approach to theory development is 'abductive' because it makes up for the limitations of inductive & deductive approaches. |

| Research Design | Phenomenology (Husserl,1927) | Phenomenology is best used because it is inherently qualitative and focuses on understanding people's lived experiences (Cope, 2005). |

| Type(s) | Hermeneutics (Heidegger, 1962) & Transcendental(Moustakas, 1994) | A person's reflection of the experience can help in interpreting the meaning discovered (Heidegger, 1962), while observing the Philosophy of presuppositionless (Husserl, 1927), which holds all personal views in abeyance. |

| Interview Structure | In-Depth (Open-Ended Questionnaires) (Hennink et al., 2010) | In-depth interview was used because it allows an informal conversation b/w the researcher & the participants. This helps the management of sensitive questions by restructuring them. |

| Data Collection | Semi-Structured | The interviews were semi-structured because it allows prompts & probes to be used. This is important since it facilitates follow-up questions. |

| Mode | Face-To-Face | The idea for a Face-To-Face interview is to manage sensitive information by reading body language and gestures during interview process (Creswell & Poth, 2017). It allows a proper interpretation of participant's responses. |

| Sampling | Purposive | The sampling is purposive because it allows the selection of qualified participants at the expense of unqualified volunteers. |

| Data Sample Size | 20 (5 Participants from each of the groups (Brazil, Nigeria, Poland & Pakistan (CSO, 2016) | The idea for mixed immigrant group is to test d/f perspectives for a better qualitative result (Saunders et al., 2016). |

| Form of Analysis | IPA (Husserl, 1970) | The choice of analysis is IPA because it reflects on participant's 'lived experiences' about the phenomenon of EOF in Ireland (Collins & Stephens, 2010). |

| Approach | Interpretivism (Abel & Myers, 2008; Dudovskiv, 2017) | By nature, phenomenology is both interpretive & descriptive |

| Perspective | Subjective (Dudovskiv, 2017) | Phenomenology rejects the objectivist view about reality, which does not agree with the research perspective. |

| Time Horizon | Cross Sectional | The interview process lasted between 2-3 Months. |

| Micro Level (20 Interviews) |

Goal | The goal of micro-level interview is to make a small theoretical contribution to knowledge. |

To ensure that the focus is on participants’ ‘lived experiences’, the use of interpretative phenomenological approach helped the author to suppress personal views and brackets personal perspectives. As the 1st phase reports, after collection of data, it was read, cleaned and reorganised for analysis. As the author believes, this enhanced data validity by ensuring that findings accurately reflect the original data through accurate representation of participants’ opinions. It further allowed data exploration by facilitating a deeper understanding of the meanings of languages used mostly by participants. In the 2nd phase, the transcripts were summarised focusing on the main questions raised by participants. Flick (2018), helped the author to avoid getting lost in a welter of details and enabled the identification of commonality, differences and relationships between the patterns that emerged. Subsequently, participants’ responses were summarised and the author selected important statements as reflected in the interpretation technique used (Harding, 2018).

The constant comparison of data in the 3rd phase generated insight by helping the author to identify patterns of similarity/difference and relationships within the data set (Barbour, 2013). Based on his best judgement, the author identified categories by going over the transcripts many times to identify broad subject areas under which data could be grouped as the 4th phase showed. This is known as ‘horizonalization’ in (Moustakas, 1994). Charmaz (2006), consequently, the transcripts were coded by selecting, separating and sorting the data as the 5th phase acknowledged (Adu, 2016).

The author achieved rigor and validity by accurately representing participants’ positions, which involved iteration and paying attention to participants’ responses. This further reflects the double hermeneutics concept in interpretative phenomenological analytical approach (i.e. about the meanings participants make out of their ‘lived experiences’ and what the authors think of these meanings based on participants’ interpretations of them). In the 6th phase, the author generated themes based on the contents in the data transcripts. The conceptual themes emerged from different sections of the transcripts and the generated codes used to illustrate different issues. Traditionally, conceptual themes were not always referred to directly because they cannot be spotted easily. They also help to achieve the most difficult aim of the analysis by building theories as part of the characteristics (Gibson & Brown, 2009). By comparing answers in the transcripts focusing on the orientation of the topic, the author generated and identified themes focusing on their aims and objectives through a constant comparative and summary approach (Harding, 2018) and by examining interview questions.

Discussion of Empirical Results

Moustakas (1994), analysing the Nigerian participants using approach for phenomenological study, they showed that their EOF is mostly influenced by their backgrounds in the forms of parental advice and career cloning. This group indicated this by showing that they are influenced by the type of businesses that their family members and friends are running. The response from one of the participants makes this clearer in the background question that was asked to identify where his inspiration originated from. In his response, he affirmed: “While I was in Nigeria, I was working part-time as a barber at a friend’s shop. Although, I was just assisting him with his business, I was motivated during my time with him and that pushed me forward to what I am doing today” (Matthew NG, 2018). In comparison, the Polish participants showed that they graduated from universities knowing what entrepreneurial career path to pursue between self-employment and traditional paid jobs. This group believed that credits should be given to the Polish educational system for making it possible to study entrepreneurship/business modules in colleges and high schools. This is reflected in the 2018 Central Statistics Report on immigrant entrepreneurs in Ireland, which confirms that the Polish immigrants in Ireland are one of the largest immigrant groups with their own businesses (CSO, 2018).

As a form of culture in the Polish educational system this group was indoctrinated in the process and this provided them with options, thus enhancing their choices to follow the selfemployment career path (Guibernau & Rex 2010). To isolate the variable factors that motivate career decisions, one of the Polish participants was asked to identify how his background played a role in his career choice. His response was: “Before I came to Dublin, the Polish environment was difficult for entrepreneurial activities. After graduation from University in Artificial Intelligence in Business, it was very difficult to find well paid job and that left me with limited options”. Prior to graduation, Marcin like most graduates was hoping for a well-paid traditional job. However, he resorted to running his own his own business subject to the difficulty in securing traditional job. Singh et al. (2013) agrees with findings in that “we found the entrepreneurs in our study-all of whom had achieved moderate success-were much more likely to have pursued internally stimulated opportunities than externally stimulated opportunities”.

Similarly, the analysis of the Pakistani community agrees with Singh et al. (2013). For instance, Faiz’s tone and his descriptions of his experience made greater emphasis regarding how he was compelled to start a business targeting the Pakistani community in Dublin. His account can be described as ‘feelings of disappointment’ and ‘discrimination’. Against all odds, Faiz would have preferred a traditional job over running his own business had the opportunity been given him. When further asked concerning his relationship with Pakistan, he stated: “What I do is influenced by culture. I belong to a community where we take responsibility ourselves. For our survival, we must be extra active and it is in our background. We basically have to be entrepreneurs”.

In the case of the Brazilian participants, it can be established that unlike the Pakistanis with a strong cultural background and religious practices with strict adherence to family business succession tradition, they were mostly influenced by indirect threats stemming from a negative political culture (Almond & Verbal, 2015). Participants from this group mostly described their politicians as corrupt because their political approach poses threats to their future and the economic well-being of Brazilians. This is evident following the response from one of the participants to identify why he left Brazil, focusing on how his reasons justified his actions and decisions to be self-employed in Ireland. He stated: “I came to Ireland because Brazil, as we speak, is very difficult. The politicians take money meant for the public and people are very poor. As a result, they have no spending power. I had to look for a better life for my wife and kids”.

In comparison, the Pakistani group showed that there is something unique about their line of businesses and approach to entrepreneurship as supported by the data. To consolidate this observation, one of the Pakistani participants was asked if he has families back home who run their own businesses. To which he affirmed: “Yes, all my family members back home run their own businesses” (Shabbiz, 2018). In response to the follow-up questions that were asked, the following were the pattern of conversation that took place between the interviewer and the interviewee: Interviewer: Tell me about your entrepreneurial background, is it something that you inherited from your family or influenced by your ethnic origin? “Shabbiz: I would say that I inherited running my own business from my family given that all my family members run their own businesses”. Interviewer: How did you identify and evaluate the business opportunity? “Shabbiz: Although this is a family line of business, I would also add that my studies in England in electronics encouraged me more and that was how this business opportunity was identified”. Thus, findings further support the argument that ‘reality’ is best experienced and does not exist independently. Based on participants’ country of origin, understanding EE as an explanatory variable factor is evident in the context because the ‘reality’ construct was presented in light of participants’ experiences.

The author thus posits that ‘experience’ is the product of phenomena encountered while living in the world of reality and therefore, a personal narrative theory. It follows that a person understands and descriptions of them are subject to the resultant emergent ‘feelings’ about that which was experienced. Leonardo described how his prior experiences back in Brazil facilitated the processes involved in setting up his own business in Dublin. For instance, in an attempt to identify the explanatory variable factors from his background and how they influence his entrepreneurial activities, he stated: “Given that I had prior experience back home before arriving in Dublin, I would say that ideologies play a significant role on how I manage my business, because I did not have to undergo new training, besides learning the Irish rules and regulations governing self-employment in Dublin”. With a deeper focus on the embeddedness of these explanatory variables and their roles (directly or indirectly), a follow-up question was asked to elicit participants’ knowledge regarding the presence of these factors in their daily entrepreneurial life. From a list of features/characteristics likely to influence career path, he further identified ‘group solidarity’, ‘willingness to work long hours’, ‘self-reliance’, ‘flexibility’, ‘business acumen, educational qualification, etc. as ethnicresources with strong effects on how he manages his business. Leonardofurther added: “I am influenced by money…as the family breadwinner; I need to make more money to support my families back home”. This further explains why he was running two separate businesses (i.e. pizza business & a supermarket) in Dublin, which employs eleven people.

In comparison, participants from other ethnic groups had different expression of views. For instance, one of the Pakistani participants showed he was influenced differently. Muhammad: “I can say that I developed this skill when I was working for someone who was running a similar business in Pakistan where mobile phones were fixed and repaired. I decided to run the same business here after my graduation in Dublin. Suffices to state that I was influenced by prior home experience and trainings in the same line of businesss”. In addition to peer-related syndrome, Muhammad was mostly influenced by predisposing explanatory variable factor(s) based on his previous encounter with his former boss. In a further observation, the following conversation with another participant was recorded: “Researcher: How did you identify and evaluate the business opportunity? Shaoiab_PA responded: Besides my personal research on this line of business, this business opportunity was identified through meeting with friends in Dublin who are also running similar businesses. Through conversations and discussions, they explained everything there is to know about the mobile phone business and that was how I learnt and was able to start my own business”.

As participants showed, their career choices were motivated by different reasons and factors. Njoku & Cooney (2018) agrees with findings in that cultural perceptions are subjective to a higher degree. In practice, each participant’s prior entrepreneurial training back home had differently affected their EOF approach. Furthermore, rigor and rigidity were achieved by creating recurrent themes based on participants’ responses. This also helped to justify research claims, thus addressing the question on whether participants’ positive responses to the questions are present in over half of the sample. Since there is no rule regarding what counts as reoccurrence (Smith et al., 2009), the creation of the recurrent themes was influenced by pragmatic concerns, thus respecting the set of criteria in (Smith et al., 2009).

Analysis and Findings

Fishman & Garcia (2016), by extension, the analysis has demonstrated that ‘entrepreneurship education’ (EE) as used in the context can further be described in light of the primordialists’ logic on ethnicity which comprises the potential to influence behaviours positively. As an explanatory variable factor, EE mostly played the role of an ‘enabler’ based on the nature of effects it had on participants. Arguably, the nature of the role played by EE in the daily activities of participants can be expounded to have multifaceted features. This is evident given that they acknowledged other possible ways their educational systems had influenced their career choices (e.g. providing them with clear career options between pursuing the traditional career path and the possibility of running own business). Agreeing with previous studies, EE was approached to represent unique characteristics that facilitated the identification of specific group’s behaviour. This was achieved through isolation of other possible variables present within the host environmental context based on participants’ descriptions of them. Per description, participants demonstrated that EE is an ethnic component with strong effects to their career choices and decision-making powers. This is evident following the nature of their entrepreneurial activities in their country of residence. As an explanatory variable factor, participants affirmed that the effects of EE can neither be suppressed by outside influences nor altered by merely being exposed to a different culture.

Participants further showed that their entrepreneurial motivations were subject to multifaceted events that originated from their country of origin. As a variable factor, this is important because the results emphasised on the need to understand that the effects of EE was instrumental to participants’ decisions to be self-employed and therefore a sources of encouragement. As a conscious act to respond to reality, the author argues that the concept of immigrant entrepreneurial activity can be described as personal idiosyncratic behaviours, which brings career fulfilment when acted upon, and or poses a threat when neglected. Participants resort to different career paths to either escape emergent threats originating from their country of residence (e.g. unemployment, discrimination at workplaces etc.) or in response to career passion.

Participants further showed that their entrepreneurial motivations were subject to multifaceted events that originated from their country of origin. As a variable factor, this is important because the results emphasised on the need to understand that the effects of EE was instrumental to participants’ decisions to be self-employed and therefore a sources of encouragement. As a conscious act to respond to reality, the author argues that the concept of immigrant entrepreneurial activity can be described as personal idiosyncratic behaviours, which brings career fulfilment when acted upon, and or poses a threat when neglected. Participants resort to different career paths to either escape emergent threats originating from their country of residence (e.g. unemployment, discrimination at workplaces etc.) or in response to career passion.

At basic level, the analysis demonstrated that the role played by EE in this context is multifaceted. Discussed in the context of ‘explanatory variable factors’, EE played the role of ‘enablers’ by empowering the study subjects with knowledge and reasons to take informed decisions regarding career options. Participants’ responses indicated that ‘EE’ encourages the pursuit of passion, career goal, curiosity, etc. as was the case with one of the Polish participants. Approached from an embedded genetic component perspective, EE demonstrated at the higher level that the perceptions of ‘culture’ on a pure intellectual level are inherently subjective. This is underpinned by collective recognition and acceptance, thus agrees with the claims in (Njoku & Cooney, 2018). EE possesses characteristics and qualities that can directly, indirectly and remotely influence behaviours and actions.

In this light, the results confirm that the concept of EE had different impact on participants’ EOF approach subject to their ethnic origins. Arguably, participants’ understanding of EE in the context discussed appears to have existed outside their consciousness because they are either pleasing or displeasing based on their current realities and experiences. This is evident given that participants in many cases were not cognizant of opportunities resulting from a specific event or phenomenon around them, which makes them either happy or sad. Until their realities became conscious experiences, the nature of an individual’s reality triggers the action that follows in response. In summary, the paper has demonstrated that the concept of EE is not only a form of culture subject to participants’ responses, it is equally powerful as other practices which have been recognised as customary because they formed the basic principles and traditions underpinning certain behaviours within a community of people. Thus, one of the ways EE can change the course of career choice is through indoctrination.

The Process of Building a Framework Model

Arguably, an entrepreneur’s ability to process knowledge and information makes him/her a lively and active economic agent. It has been established that in order to understand entrepreneurial processes, the need to have knowledge of the values, characteristics and actions of the entrepreneur over time is paramount (Nassif et al., 2010). Subject to the world view that conceptualises processes, rather than objects, the ‘Process Theory’ is underpinned by the basic building blocks of how the world around us is understood (Moroz & Hindle, 2012). Thus, the two most provocative questions often asked in this field of research are: what do entrepreneurs do differently from managerial functions and how do they do it (Busenitz & Barney, 1997; Leibenstein, 1968)? As process related questions, understanding the processes underpinning immigrant entrepreneurial opportunity formation activity is invaluable. Bygrave (2007) affirms that a process-focussed approach offers much unexplored potential for understanding, if not unifying, a highly disparate research domain. Hence, making entrepreneurial process universal is important for the benefits of this field of study. Using Process Theory to frame academic examination of entrepreneurial actions informs several researched themes and issues prominently related to entrepreneurship and have equally produced several insightful observations.

Scholars have established that building an immigrant entrepreneurial model follows a stage-like approach that divides the processes into major phases (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Although, a stage-like approach to this process building simplifies the different phases involved, it has been criticised because it fails to reflect the interactions of different components (i.e. explanatory variable factors) representing the true positions of the different actors in the process theory) (Moroz & Hindle, 2012). In addition to static, stage and the dynamic as the three additional immigrant EOF process models (Baltar & Icart, 2013; Aliaga-Isla & Rialp, 2012), immigrant entrepreneurial model captures both the sequences of actions and the temporal order from which the practices of their EOF processes are created and thus advantageous.

The relationship between the different actors and the temporal sequences of the actions present during the EOF process is identified as important activities in the dynamic process model (Evansluong, 2016). Similarly, the nature of the relationship that exists between immigrant entrepreneurs (IEs) and the different actors in both countries is identified in the static process model (ibid). For example, while ‘motivation for migration’, educational culture, family traditions, etc. are some of the environmental actors from immigrants’ country of origin, ‘access to capital’, ‘entrepreneurial opportunities’, ‘institutional support’, etc. are some of the environmental actors from their country of residence that influence the type and level of entrepreneurial actions they carryout (Johnson et al., 2007). Similarly, the stage process model aims at showing immigrant entrepreneurial actions in sequence Aliaga-Isla & Rialp (2012), it was criticized for its failure to acknowledge the existence of interaction between the different actors. To discover opportunities, IEs used other process models, which include: (i) through knowledge acquired in the home and host country during pre-migration period; and (ii) through migrant’s predisposing skills (e.g. EE). Even though the ‘static’ process model can illustrate the relationship between IEs and the different actors in the home and host countries, it was criticised because it is unable to show the sequence of IEs’ activities (Castells, 2010).

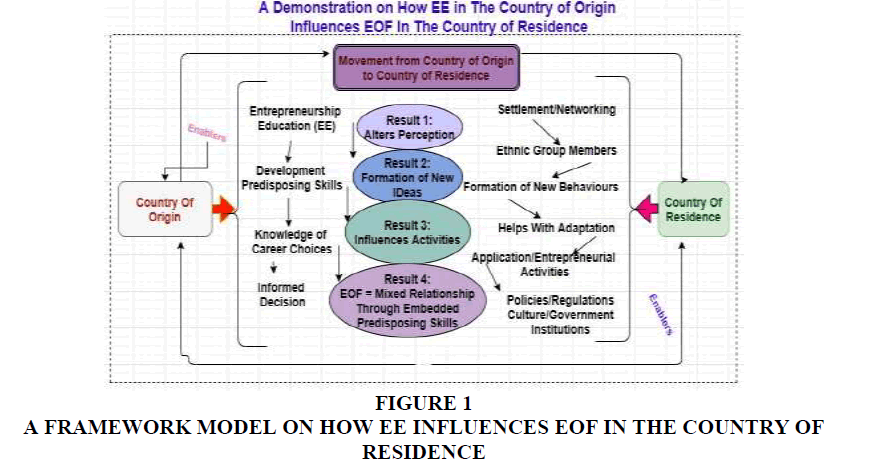

Arguably, while the criticisms in the previous models were abstract to the topic in context, they facilitated the initiatives taken in building the current study model framework not only to address the loopholes identified, but to expand knowledge by showing how Entrepreneurship Education (EE) as a cultural variable influences immigrant entrepreneurial idiosyncrasies in their country of residence during the formation of opportunities. Thus, the model framework below visually demonstrates the sequence of an immigrant’s entrepreneurial actions and interactive processes to show how their embeddedness has been recognised as a cultural practice manifested through action. In agreement with Foley (2008), entrepreneurial actions have strong effects of social networking because entrepreneurs’ decisions are influenced by their embeddedness in the social context. Such embeddedness with social networking activities and relationship are described as ‘integration’ into new cultures (Kloosterman & Rath, 2001).

In the model framework below, the author expounds how EE (as a cultural explanatory variable) influences immigrant entrepreneurial opportunity formation practices to reflect their entrepreneurial activities. Although, the mixed embeddedness theory acknowledges the existence of connections between immigrants’ ethnic origins and their opportunity formation approach (Kloosterman et al., 1999), the current model demonstrates how other ethnic variable factors (i.e. EE) affect immigrants’ Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation (EOF) activities in their country of residence using an interactive mode approach. The figure below thus depicts how EE as a variable factor not only enables the pursuit for self-employment in the country of residence, but equally influences how immigrants engage in creating new business opportunities in response to embedded predisposing skills.

Figure 1 captures the processes involved during Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation (EOF), thus demonstrating how variable factors in the forms of home-country predisposing skills influences decision making during the creation of new opportunities in the host country. As the figure further shows, through Entrepreneurship Education (EE) and training, immigrants acquire entrepreneurial skills which help them deal with career challenges such as: career choices, decision-making, etc. Approached under the rubrics of variable factors, EE plays dual roles; (i) it enables an individual to pursue the entrepreneurial path subject to embedded predisposing skills acquired through EE and training in the country of origin; (ii) it provides sufficient information that facilitates informed decision-making process on whether or not to follow the traditional career path.

As previous studies acknowledged Njoku & Cooney (2018), the framework analogy posits that immigrants bring with them predisposing skills acquired through EE in their country of origin. As embedded enabling factors, immigrants are subject to new changes that facilitate their adaptations in their country of residence. During the first few weeks and months of their arrival, these skills are described as latent because they are yet to be activated and put to action. Often immigrants are proactive and are able to settle and network with other ethnic members who through additional trainings. This helps them to prepare and adapt into the host country by forming new behaviours and becoming law abiding. Consequently, the concept of what constitutes ‘acceptable conduct’ in their county of residence becomes their primary goal. This becomes the basic foundation that guide and govern their day to day life activities in their country of residence. Following the logic in Evansluong (2016), immigrant entrepreneurial activity is affected by mixed relationship. As an ‘enabler’, the model framework thus concludes that the impact of EE in country of origin reflects on immigrants’ entrepreneurial activities as explanatory variable factors. This influences immigrants’ EOF in country of residence through the utilization of embedded predisposing skills as their choices of business formation show.

Conclusion

While the concept of EE has been explored differently based on the study context, the current paper adopted the view that EE can be examined from the view of explanatory variable factor, capable of influencing entrepreneurial behaviour. Besides providing students with important tools to make career related decisions and choices, this paper has established that EE has the potential to influence entrepreneurial activities in the host country as a variable factor taking the form of predisposing skills that immigrants bring to entrepreneurship. This is important because it highlights the need to examine EE beyond its economic benefit to indicate how EE influences EOF amongst immigrant entrepreneurs in their country of residence.

Furthermore, this paper explored EE as an emergent cultural enabler originating from immigrants’ country of origin. As the paper showed, EE plays multifaceted roles on immigrant Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation (EOF) activities in their country of residence. This is important because it helped the author to examine ‘education’ and ‘culture’ separately to show how these relate based on an objective review of what constitutes ‘reality’ using participants’ descriptions of their experiences. Thus, the knowledge that EE embodies cultural components subject to its embeddedness in a system highlights its ability to control individual willpower, decisions and choice making.

By showing that what constitutes culture is subject to its acceptance in the society, participants to the study demonstrated that EE as used in the context constitutes a recognised tradition, which has gradually become part of their educational system and as such, formed the basic foundation of life. Using a phenomenological qualitative analytical procedure, data was collected from 20 immigrant entrepreneurs from Brazil, Nigeria, Poland and Pakistan. Comparable to other participants to the study, the Polish group acknowledged that they mostly took to self-employment as a result of their educational system, which helped them developed entrepreneurial mind-sets through indoctrination. With this, participants were able to make informed choices between the traditional and self-employment career path. As participants’ entrepreneurial activities showed, the model framework thus expounded how EE facilitated EOF through decision making, subject to its embeddedness in the system. Thus, EE in country of origin influence EOF in country of residence by acting as an ‘embedded enabling factor’ reflected in participants’ entrepreneurial activities through choices, decision-making and the type of businesses participants

References

Adu, P. (2016). Presenting qualitative findings: Using NVivo output to tell the story.

Aliaga-Isla, R., & Rialp, A. (2013). Systematic review of immigrant entrepreneurship literature: previous findings and ways forward.Entrepreneurship & Regional Development,25(9-10), 819-844.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Almond, G.A., & Verba, S. (2015).The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton university press.

Alvarez, S.A., Barney, J.B., & Anderson, P. (2013). Forming and exploiting opportunities: The implications of discovery and creation processes for entrepreneurial and organizational research.Organization Science,24(1), 301-317.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Axman, A. (2003).Ultimate Small Business Advisor (with CD). Entrepreneur Press

Baker, T., & Nelson, R.E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage.Administrative Science Quarterly,50(3), 329-366.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baltar, F., & Icart, I.B. (2013). Entrepreneurial gain, cultural similarity and transnational entrepreneurship.Global Networks,13(2), 200-220.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barbour, R. (2013).Introducing qualitative research: a student's guide. Sage. (2008)

Bhave, M.P. (1994). A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation.Journal of Business Venturing,9(3), 223-242.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Breat, J. (2009). ECEI2009-4th European conference on entrepreneurship and innovation: ECEI2009. Academic Conferences Limited.

Brush, C.G., Kolvereid, L., Widding, L.O., & Sorheim, R. (2010).The Life Cycle of New Ventures: Emergence, Newness and Growth. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Burkhart, T., Krumeich, J., Werth, D., & Loos, P. (2011). Analyzing the business model concept—a comprehensive classification of literature.

Busenitz, L.W., & Barney, J.B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making.Journal of Business Venturing,12(1), 9-30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bygrave, W.D. (2004). The Entrepreneurial Process inThe portable MBA in entrepreneurship. John Wiley & Sons.

Bygrave, W.D. (2007). 'The Entrepreneurship Paradigm'Revisited Seventeen Years Later.

Castells, M. (2010). The rise of the network society (with a new pref).Chichester, West Sussex.

Charmaz, K. (2006).Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. sage.

Che, A.A.M.A. (2016). Linking instrumentalist and primordialist theories of ethnic conflict.E-International Relations,1, 14-19.

Cherukara, J.M., & Manalel, J. (2011). Evolution of Entrepreneurship theories through different schools of thought. InThe Ninth Biennial Conference on Entrepreneurship at EDI, Ahmedabad.

Creswell, J.W., & Poth, C.N. (2017).Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

Cyert, R.M., & March, J.G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm.Englewood Cliffs, NJ,2(4), 169-187.

De Vries, H.P. (2007). The influence of migration, settlement, cultural and business factors on immigrant entrepreneurship in New Zealand.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Evansluong, Q.V. (2016). Opportunity creation as a mixed embedding process.

Fishman, J.A., & García, O. (2016).Handbook of language and ethnic identity. Oxford University Press, USA.

Flick, U. (2018).An introduction to qualitative research. Sage Publications Limited.

Foley, D. (2008). Does culture and social capital impact on the networking attributes of indigenous entrepreneurs?Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy,2(3), 204-224.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Getzels, J.W., Lipham, J.M., & Campbell, R.F. (1968).Educational administration as a social process: Theory, research, practice. Harpercollins College Division.

Gibson, W., & Brown, A. (2009).Working with qualitative data. Sage.

Guibernau, M., & Rex, J. (2010).The ethnicity reader: Nationalism, multiculturalism and migration. Polity.

Halkias, D., & Adendorff, C. (2016).Governance in immigrant family businesses: Enterprise, ethnicity and family dynamics. Routledge.

Hallinger, P., & Leithwood, K. (1996). Culture and educational administration.Journal of Educational Administration.

Harding, J. (2018).Qualitative data analysis: From start to finish. SAGE Publications Limited.

Hastie, R. (2001). Problems for judgment and decision making.Annual review of psychology,52(1), 653-683

Johnson, J.P., Muñoz, J.M., & Alon, I. (2007). Filipino ethnic entrepreneurship: An integrated review and propositions.International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal,3(1), 69-85.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kennedy, J.F. (2018).A nation of immigrants. HarperCollins.

Kloosterman, R., & Rath, J. (2001). Immigrant entrepreneurs in advanced economies: mixed embeddedness further explored.Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,27(2), 189-201.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kloosterman, R., Van Der Leun, J., & Rath, J. (1999). Mixed embeddedness:(in) formal economic activities and immigrant businesses in the Netherlands.International Journal of Urban and Regional Research,23(2), 252-266.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kuratko, D.F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,29(5), 577-597.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Leibenstein, H. (1968). Entrepreneurship and development.The American Economic Review,58(2), 72-83.

Lemes, P.C., Almeida, D.J.G., & Hormiga, E. (2010). The role of knowledge in the immigrant entrepreneurial process.International Journal of Business Administration,1(1), 68.

Longenecker, J. G. (2009).Small business management: Launching and growing new ventures. Cengage Learning.

Low, M.B., & MacMillan, I.C. (1988). Entrepreneurship: Past research and future challenges.Journal of Management,14(2), 139-161.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2016).Designing qualitative research. Sage publications.

Matlay, H. (2006). Researching entrepreneurship and education.Education+ Training.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McKeever, E., Anderson, A., & Jack, S. (2014). Entrepreneurship and mutuality: social capital in processes and practices.Entrepreneurship & Regional Development,26(5-6), 453-477.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McMullen, J.S., & Shepherd, D.A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur.Academy of Management Review,31(1), 132-152.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moroz, P.W., & Hindle, K. (2012). Entrepreneurship as a process: Toward harmonizing multiple perspectives.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,36(4), 781-818.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moustakas, C. (1994).Phenomenological research methods. Sage.

Nassif, V.M.J., Ghobril, A.N., & Silva, N.S.D. (2010). Understanding the entrepreneurial process: a dynamic approach.BAR-Brazilian Administration Review,7(2), 213-226.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Njoku, K.C., & Cooney, T.M. (2018). Understanding How Immigrant Entrepreneurs View Business Opportunity Formation Through Ethnicity.Creating Entrepreneurial Space: Talking Through Multi-Voices, Reflections on Emerging Debates, 49.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Njoku, K.C., & Cooney, T.M. (2020). The Influence of Ethnicity on Entrepreneurship Opportunity Formation (EOF) Amongst Immigrants. InDeveloping Entrepreneurial Competencies for Start-Ups and Small Business. 192-214. IGI Global.

Ojala, A. (2016). Business models and opportunity creation: How IT entrepreneurs create and develop business models under uncertainty.Information Systems Journal,26(5), 451-476.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., & Tucci, C.L. (2005). Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept.Communications of the Association for Information Systems,16(1), 1.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Peters, M. (2001). Education, enterprise culture and the entrepreneurial self: A Foucauldian perspective.The Journal of Educational Enquiry,2(2).

Ram, M., Sanghera, B., Abbas, T., Barlow, G., & Jones, T. (2000). Ethnic minority business in comparative perspective: the case of the independent restaurant sector.Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,26(3), 495-510.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rasmussen, E.A., & Sørheim, R. (2006). Action-based entrepreneurship education.Technovation,26(2), 185-194.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students, (no. Book, Whole).Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Singh, R.P., & Gibbs, S.R. (2013). Opportunity recognition processes of black entrepreneurs.Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship,26(6), 643-659.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Smith, J.A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009).Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage.

Solomon, G., & Matlay, H. (2008). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial outcomes.Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Timmons, J. A. (1990).New business opportunities: getting to the right place at the right time. Brick House Pub Co.

Vinogradov, E., & Elam, A. (2010). A process model of venture creation by immigrant entrepreneurs.The Life Cycle of New Ventures: Emergence, Newness and Growth, 109-126.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—conceptual challenges and ways forward.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,35(1), 165-184.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wielemans, W., & Chan, P.C.P.(1992).Education and culture in industrializing Asia: the interaction between industrialization, cultural identity, and education: a comparison of secondary education in nine Asian countries(Vol. 13). Leuven University Press.

Williams, J.L., & Gentry, R.J. (2017). Keeping it real: The benefits of experiential teaching methods in meeting the objectives of entrepreneurship education. Emerald Publishing Limited, 27, 9-20.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The business model: recent developments and future research.Journal of Management,37(4), 1019-1042.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 17-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AJEE-22-12686; Editor assigned: 19-Oct -2022, Pre QC No. AJEE-22-12686(PQ); Reviewed: 02-Nov-2022, QC No. AJEE-22-12686; Published: 09-Nov-2022