Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 6

What they don't Teach at Entrepreneurship Institutions? An Assessment of 220 Entrepreneurship Undergraduate Programs

Kamran Siddiqui, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University

Adel Alaraifi, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University

Citation Information: Siddiqui, K., & Alaraifi, A. (2019). What they don’t teach at entrepreneurship institutions? An assessment of 220 entrepreneurship undergraduate programs. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 22(6).

Abstract

The purpose of this exploratory research is to analyse the contents taught in undergraduate entrepreneurship programs. A total of 220 undergraduate programs were selected from the all around the world offering Entrepreneurship undergraduate programs (including BBA, BA, BS, B.Sc) in English language. Data was collected from official websites of the respective institutions. 48 programs were excluded from further processing and 164 programs were finalised for further processing. This paper recommends many improvement in Entrepreneurship curriculum and development which includes (a) need for change of mind-set from ‘Corporate success’ to ‘Entrepreneurial Success’; (b) need for separate accreditation system of Entrepreneurship programs; (c) need for ‘School of Entrepreneurship’ or ‘College of Entrepreneurship’ separate from ‘Business School’; (d) Need to establish and follow a new standardized name of the degree titled as ‘Bachelors of Entrepreneurship’ with abbreviation ‘B.Ent.’; (e) need for linking Entrepreneurship curriculum with Entrepreneurial eco-systems rather than linking it with job placement services; and (f) need for customization of existing Entrepreneurship curriculum for the specific needs for future entrepreneurs.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurship Curriculum, Entrepreneurship Institutions, Entrepreneurship Undergraduate Programs, BBA Entrepreneurship, BA Entrepreneurship, BS Entrepreneurship.

Introduction

The history of entrepreneurship education spans over a century and has evolved over many phases. Started as a single course on “Small Business Management” at University of Michigan in 1927 (Zell Lurie Institute for Entrepreneurial Studies, University of Michigan, official website, 2019). The first course designed specifically to teach entrepreneurial management titled as “The Management of New Enterprises” was introduced in 1947 at Harvard Business School offered to returning veterans of World War II (Harvard business School, official website, 2019). This was followed by New York University with a course on Entrepreneurship and Innovation in 1953 taught by Peter Drucker (Cooper, 2003). In 1950s, many universities including University of Illinois, Stanford University, and MIT started offering Entrepreneurship courses. In 1967, Stanford University and New York University started offering MBA Entrepreneurship (Katz, 2003). University of Texas at Austin started of its entrepreneurship education program in 1964 (University of Texas at Austin, Offical Website, 2019). Babson College was the first to offer undergraduate program in Entrepreneurship in 1967. For last fifty years, almost all top business schools are offering some form Entrepreneurship education in their portfolio of programs.

Entrepreneurship education has seen emergence of Entrepreneurship centres as part of Business schools or an as separate entities. This includes Zell Lurie Institute for Entrepreneurial Studies at Ross School of Business, University of Michigan; Arthur Rock Centre for Entrepreneurship at Harvard business School, Herb Kelleher Centre for Entrepreneurship at University of Texas at Austin; Arthur M. Blank Centre for Entrepreneurship at Babson College, Lloyd Greif Centre for Entrepreneurial studies, University of Southern California and many more. More recently, on-campus/off-campus business incubators and accelerators augment Entrepreneurship education.

During last two decades, most of the business schools have started offering Entrepreneurship curriculum as part of their product portfolio. Their curriculum on ‘Entrepreneurship’ specific programs are not tailored for the specific needs for entrepreneurs. This inference is based of four observations. Firstly, some institutions have renamed their degrees to incorporate ‘Entrepreneurship’ word as BBA Entrepreneurship, BA Entrepreneurship, and BSc Entrepreneurship. Curriculum in these programs resembles 80% to Business education programs. Secondly, program learning objectives in these ‘Entrepreneurship’ specific programs aimed at producing managers not entrepreneurs. Curriculum mix is also gearing students towards corporate culture not start-up culture. Finally and probably most importantly most of the business schools are still relying on placement services for placement of their graduates including entrepreneurship graduates. While entrepreneurship graduates need complete entrepreneurship ecosystem to get their start-ups going and most of business schools offering ‘Entrepreneurship’ specific programs lack the connectivity with international or regional Entrepreneurship ecosystems. Hence, resulting at higher level of disappointment to society in general and graduating students in particular. It has also been observed that undergraduate degree in entrepreneurship does not catch an eye of a recruiter.

While several schools have launched their own entrepreneurship programs recently, only a few schools have spearheaded the change. These schools include University of Southern California, Babson College, Wichita State University, and Baylor University, (Kent, 1990). The entrepreneurship programs of these schools have excelled along at least one dimension and each has its own distinct contribution to program development. For example, Baylor University has created programs and courses that provide students with greater exposure to the side of entrepreneurship that is more unstructured in nature, (Kent, 1990).

Literature Review

Over the past two decades, the field of entrepreneurship has become one of the strongest economic forces that the world has experienced, (Kuratko & Hodgetts, 2004). The growth of this field has simultaneously brought about an (Raposo & Do Paço, 2011) expansion in the domain of entrepreneurship education. The European Commission (2008) defines entrepreneurship as an individual’s ability to convert ideas into action, and the process includes innovation, creativity, and risk-taking, along with the planning and management of projects to achieve objectives, (Raposo & Do Paço, 2011). An entrepreneurship education is likely to produce more entrepreneurs than in the past, who are likely to know better how, where, and when to launch their new ventures, (Kent, 1990). They will also know how to achieve and pursue their entrepreneurship careers and goals. The Consortium for Entrepreneurship Education (2008) believes that entrepreneurship education is not just limited to teaching how to run a business; it is about promoting creative thinking, empowerment, and a strong sense of one’s self, (Raposo & Do Paço, 2011). It also teaches one how to recognize opportunities in their life, how to pursue opportunities through idea generation and resource discovery, how to create and operate a new firm, and how to think creatively and critically, (Raposo & Do Paço, 2011). It is also believed that entrepreneurship education also develops certain belief, attitudes and values within a person and encourages them to consider other alternatives to paid employment or unemployment (Holmgren et al., 2005); university training for entrepreneurial competencies, it’s impact on intention of venture creation (Sánchez, 2010).

The oldest entrepreneurship courses were introduced in the 1940s and by 1970, around 24 schools had offered entrepreneurship related courses, separate from small business courses, (Kent, 1990). This number had grown drastically by 1975 in which more than a hundred business schools had introduced entrepreneurship courses which focused majorly on new venture creation, (Kent, 1990). By 1985, the total number of courses had almost tripled, in just AACSB schools alone, (Vesper 1985). Hence, entrepreneurship as an educational program had established itself and since then has undergone numerous revisions in curricular approaches and concepts being tested inside the classroom, (Kent, 1990). Hundreds of business schools offer at least one course in entrepreneurship and some offer it as a mandatory course. Others offer it as an elective or as a substitute to a business introductory course, (Kent, 1990). Several academic events in recent years have shaped the growing interest in the field of entrepreneurship. These include a realization that the traditional MBA is no longer a right fit for entrepreneurs and potential managers due its low risk and short-term focus (Hayes & Abernathy, 2007; Behrman & Levin, 1984; Peters et al., 1982; Cheit, 1985). Other factors are a growing acceptance that entrepreneurship can be learned and is teachable (Drucker, 1985), Innovation and entrepreneurship practices and principles, 1985), increasing demand for entrepreneurship courses and programs by students and alumni, development of entrepreneurship-related course material (Ronstadt, 1984; Stevenson et al., 1989; Timmons et al., 1985), and growing awareness that individuals who have started their own businesses are usually the most generous of alumni donors, (Kent, 1990).

Over the years, there has been a transition from an old school of entrepreneurship to a new school of entrepreneurship. The old school preaches not to overthink about the venture and to just go for it, find any opportunity and implement it, wait until you are thirty-five to start your own venture, draw a business plan first, not to pay attention to ethical issues, and defined entrepreneurial success as a function of the right human characteristics and traits, (Kent, 1990). On the other hand, the new school preaches entrepreneurs to be critical thinkers as well as action-oriented to be successful, considers any age to be the right age for starting a venture but favours late 20s and early 30s more, encourages the drawing of a creative venture feasibility analysis over a business plan, gives importance to other entrepreneurial issues as well and not just on venture start-up, considers ethical assessment as an important component of entrepreneurship, and describes entrepreneurial success as a function of know-how and know-who, (Kent, 1990).

Furthermore, Kent (1990) listed several skills that an entrepreneurship education or course ought to equip potential entrepreneurs with: reality testing skills, fact versus myth about entrepreneurship, opportunity identification skills, creativity skills, venture evaluation skills, ambiguity tolerance skills and attitudes, venture strategy skills, venture start-up action skills, environment assessment skills, career assessment skills, ethical assessment skills, contacts-networking skills, deal-making skills, and harvesting skills, (Kent, 1990). Also, it is suggested that entrepreneurship education aims to propose to people, including the youth and enterprising individuals and entrepreneurial thinkers, to be responsible, (Raposo & Do Paço, 2011).

A three-category framework for entrepreneurship education was also suggested in the literature that included (a) education about enterprise, (b) education in enterprise, and (c) education for enterprise, (Jamieson, 1984). Education about enterprise is concerned primarily with awareness creation, and aims to educate students about setting up and running a business. Education in enterprise involves management training for already established entrepreneurs and is focused on ensuring the development and expansion of the business. Education for enterprise is concerned with training aspiring entrepreneurs and preparing them for a self-employed career, and encourages participants to start and run their own business, (Jamieson, 1984).

Some researchers claim that entrepreneurship education research is mainly focused on university level or secondary school (Raposo et al., 2008, Sánchez, 2009). Several academicians and authors argue that the educational process starts before this, e.g. Landstron and Sexton (2000) claim that children at birth are considered entrepreneurial, (Landstron & Sexton, 2000). Hence, they recommend that entrepreneurship education should start at the earliest age possible.

After skimming through literature three generalization could be made; Firstly, various studies were conducted on Entrepreneurship education highlighting paedogical impairments in the subject area but earlier studies failed to differentiate Entrepreneurship curricula with other business curriculum. Secondly, the extent and nature of education required by modern aspiring entrepreneurs is not well understood (Mcmullan & Long, 1987) and it addresses the change of mind required from ‘Corporate education’ to ‘Entrepreneurial education’. Thirdly, earlier studies failed to address major degree nomenclatures required to award degree in Entrepreneurship. Fourth, earlier studies could not stress the need to link Entrepreneurship curriculum with Entrepreneurial eco-system. Previous studies could not emphasize the need for customization of existing Entrepreneurship curriculum for the specific needs for future entrepreneurs. Earlier studies could not highlight the need for separate accreditation system of Entrepreneurship programs.

Methodology

This descriptive study adopts a quantitative approach (Mingers, 2003). In the first phase two focus groups were conducted with the faculty members teaching Entrepreneurship subjects in different university throughout the world during a dedicated Entrepreneurship conference. Based on the literature gaps identified and the initial findings of the focus groups research question was formulated; (a) What are the program contents in undergraduate entrepreneurship programs?

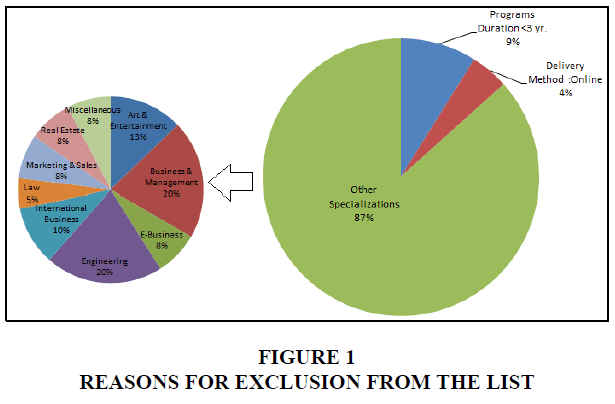

A total of 220 undergraduate programs were selected from the all around the world [19 countries] offering Entrepreneurship undergraduate programs (including BBA, BA, BS, BSc) in English language. Data was collected from official websites of the institutions during summer 2018 and major fields included (a) Degree & Title of the program (BBA, BA, BS, BSc); (b) Annual Tuition Fees; (c) Duration of Program; (d) Name, City and Country of the university /institution; (e) Courses offered in different years. All programs meet the above mentioned criteria were selected and their data was downloaded. All efforts were made to make the list all inclusive. At second stage a multiple criteria was applied to scrutinize the undergraduate programs for further processing. The shortlisting criteria inlcude all programs must be (a) offered on full-time bases; (b) in English language; (c) having a physical campus and infrastructure; (d) with minimum duration of 3 years; (e) offering Entrepreneurship as a major subject. This has resulted in excluding 48 programs further processing and shrinking the list of programs to 164. Many excluded programs were offering Entrepreneurship as minor specialization and degree titles were other than Entrepreneurship for example Engineering, Entertainment, International Business, Real Estate, Legal Studies, Sales, Biology, Community, Sports and Vocational (Figure 1 Reasons of Exclusion).

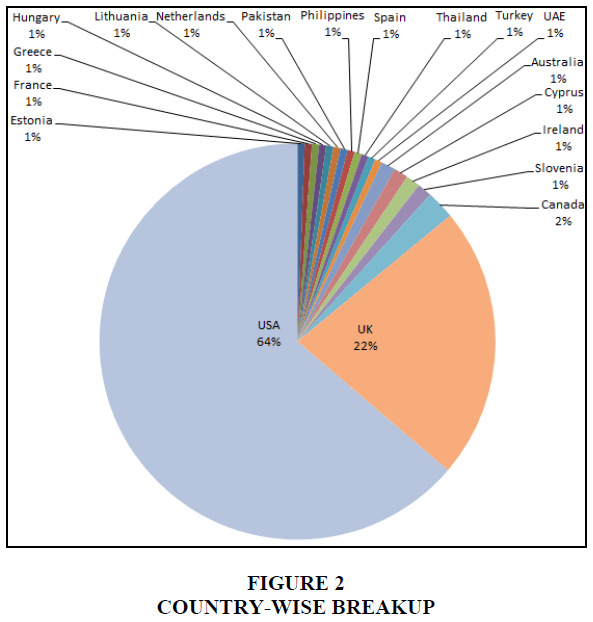

168 Entrepreneurship programs from 19 different countries meeting the above mentioned criteria considered for further analysis. 64% programs were originated from USA and 22% from UK rest of 17 countries have one or two programs in the final list. Although Canada, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand are large English speaking countries but not many institutes offer ‘Entrepreneurship’ specific programs so these were not included in this list of programs. This diversified list of countries has made it easier to generalize the findings from this research (Figure 2).

Analyses

This paper aims to provide multiple analyses. Firstly it provides descriptive analysis which includes (a) Types of entrepreneurship educational institutions; (b) Types of entrepreneurship educational programs. At a later stage, this research will also provide curriculum mix used by various universities highlighting needed curriculum for an entrepreneurial eco-system.

Degree Titles of Entrepreneurship Programs

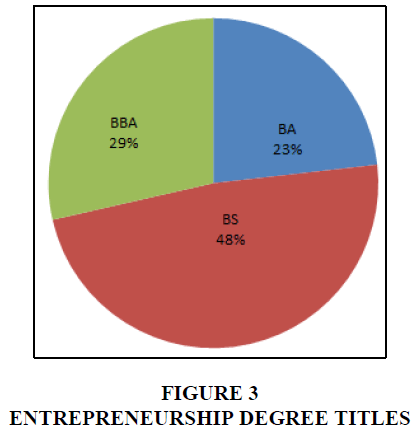

The recent development and growth in the programs and curricula for the field of entrepreneurship and start-up creation has been outstanding, (Kuratko, 2005). Different kinds of entrepreneurship programs, majority being bachelors, are offered around the world. Three major degree nomenclatures were studied for this study (a) Bachelor of Science (BSc/BS); (b) Bachelor of Arts (BA) and (c) Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) (Figure 3). Three observations were made from this analysis; (a) BBA programs are normally offered by Business Schools; (b) BS/BSc programs are offered with quantitative methods courses as compared to BA programs; (c) BA programs are more common in Europe.

Entrepreneurship Institutions

The number of universities and colleges offering entrepreneurship-related courses has increased from a just a few in the 1970s to more than 1,600 in 2005. Both universities and institutes offer entrepreneurship education and programs. The type of instruction varies between on-campus to online. Also, it is not just business schools that are offering entrepreneurship courses; community colleges, engineering schools, and junior colleges are increasingly introducing entrepreneurship related courses as part of their curriculum, (Kent, 1990). At least 50 different engineering schools have offered entrepreneurship as an elective course, (Vesper, 1984). One observation was made during the analyses phase; although there are many business schools offering entrepreneurship undergraduate programs, there is no distinct brand name is available as ‘School of Entrepreneurship’ or ‘College of Entrepreneurship’ at top institutions of the world. This leads to a further discussion that is it possible for business schools to offer two different programs (Business versus Entrepreneurship) satisfying two different mind sets (Job Seekers versus Job Creators) with a similar curriculum. This paper is an attempt to answer to this critical question and decision has been rested with fine judgment of readers.

Broader Subject Categories Taught in Entrepreneurship Educational Programs

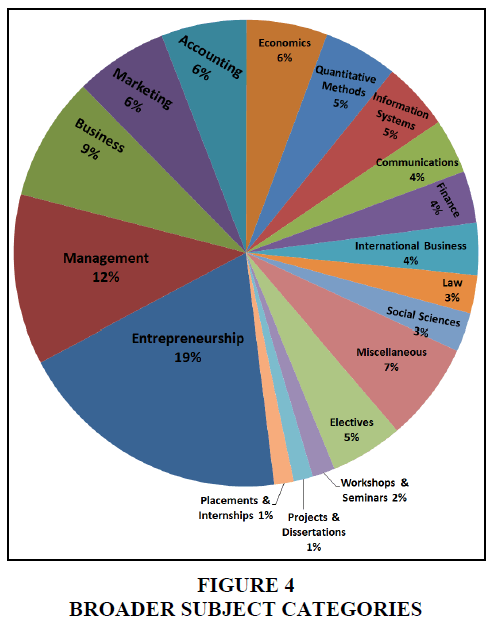

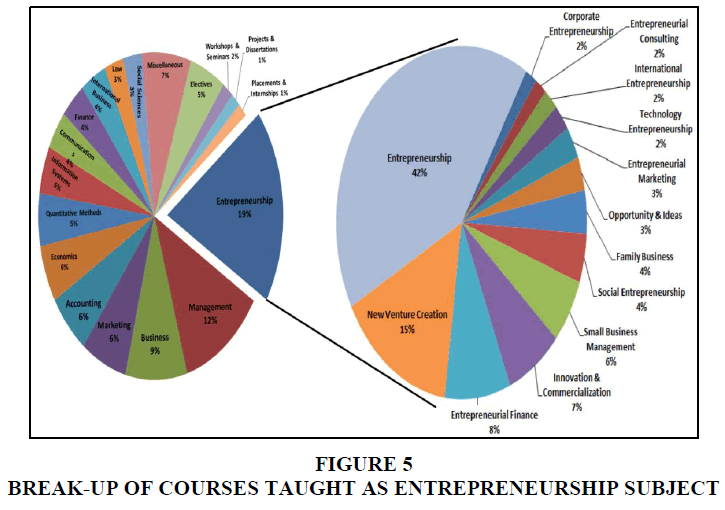

Similar to any other business degree Entrepreneurship programs also offer breadth of courses rather than depth for any individual discipline (Figure 4). Entrepreneurship and relevant courses constitute only 19% of the curriculum which looks like Entrepreneurship is offered as a major in Business discipline not as a separate discipline (Figure 5). 81% courses are taught with a corporate mind-set and probably mixed with students ambitious to get ‘good jobs’ rather than to make their own start-ups (Figures 4-15).

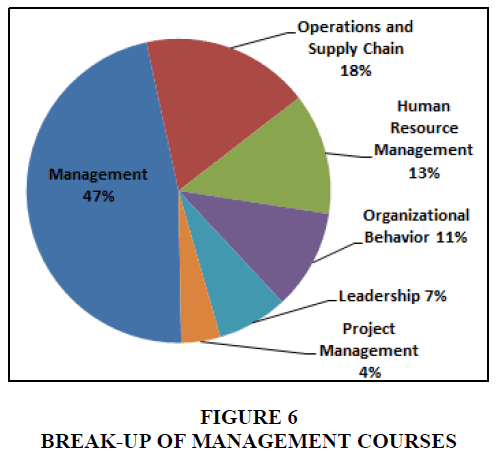

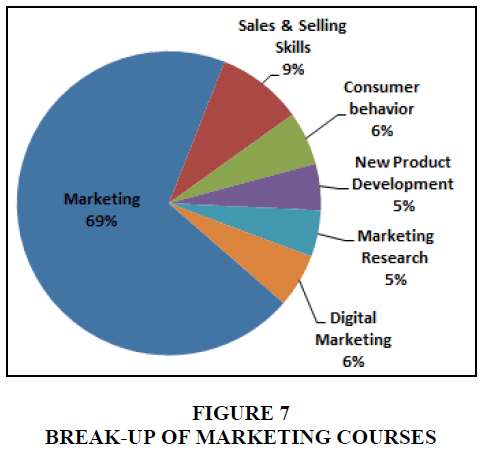

Figure 6 shows a break-up of Management courses offered as part of entrepreneurship curriculum. Like all other courses Management courses are similar to the courses offered to business degrees. Leadership courses have smaller weightage for future entrepreneurs. Strength of successful entrepreneurs is always seen as use of effective and efficient marketing tools. This requires greater reliance on Entrepreneurial marketing tactics rather corporate marketing tools including advertising and branding. Digital marketing has relatively smaller proportion in the entrepreneurship curriculum portfolio (Figure 7).

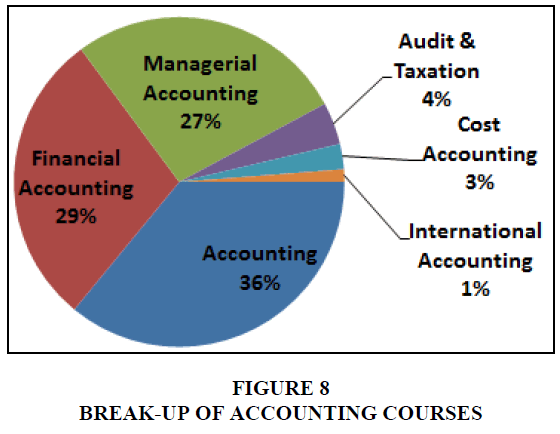

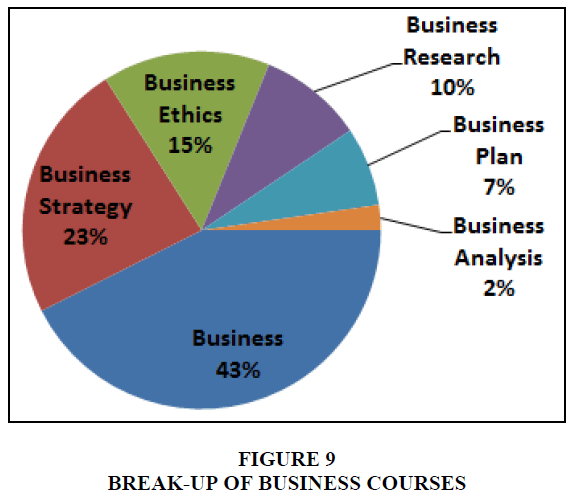

Figure 8 shows break-up of Accounting Courses in Entrepreneurship curriculum. Audit, Taxation and Cost accounting courses are needed to be given more weightage rather than Financial Accounting for future entrepreneurs. Figure 9 shows break-up of Business courses in Entrepreneurship curriculum. Teaching Business feasibility studies may be considered as missing in all entrepreneurship programs included in this study.

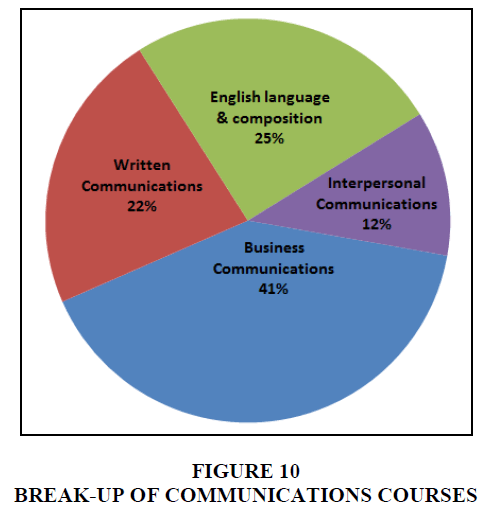

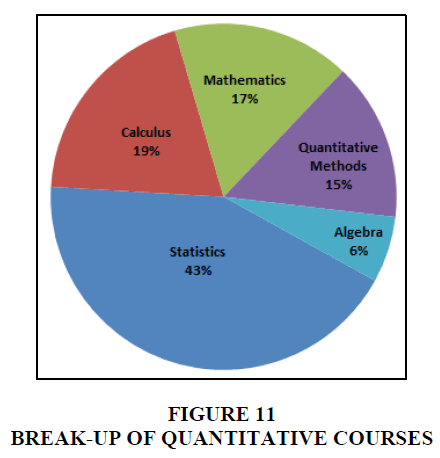

Figure 10 shows break-up of Communications courses in Entrepreneurship curriculum. Still writing business, technology and economic feasibility reports and presentation and pitching new ideas are absent in almost all Entrepreneurship programs studied for this research. Figure 11 shows break-up of Quantitative courses in Entrepreneurship curriculum. Significant time and resources were spent teaching algebra and calculus to future entrepreneurs which seems redundant now days.

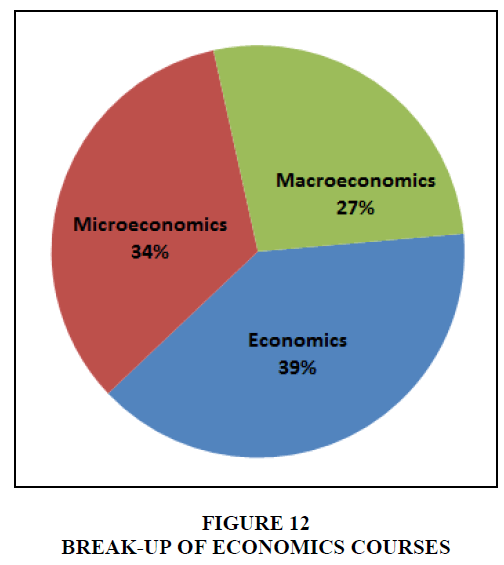

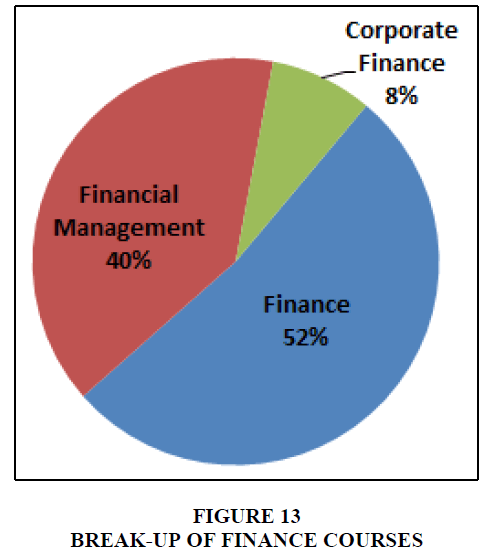

There is greater need to teach future entrepreneurs for macroeconomic indicators for launching new ventures while current curriculum emphasizes more on micro-economics (Figure 12). Corporate Finance and Financial Management courses (Figure 13) are taught with large size corporations in mind while business start-ups need customization of finance curriculum for start-ups.

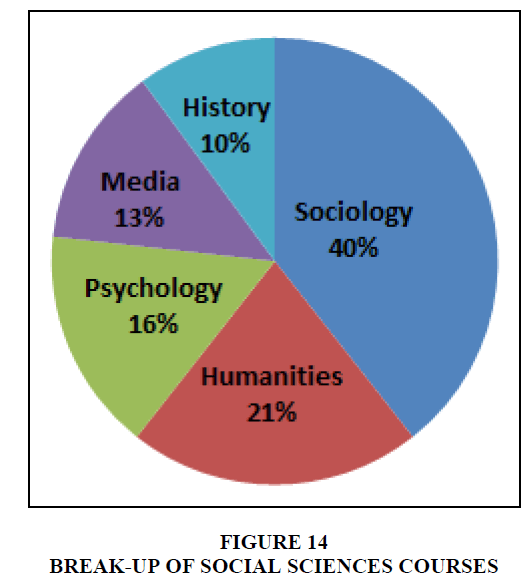

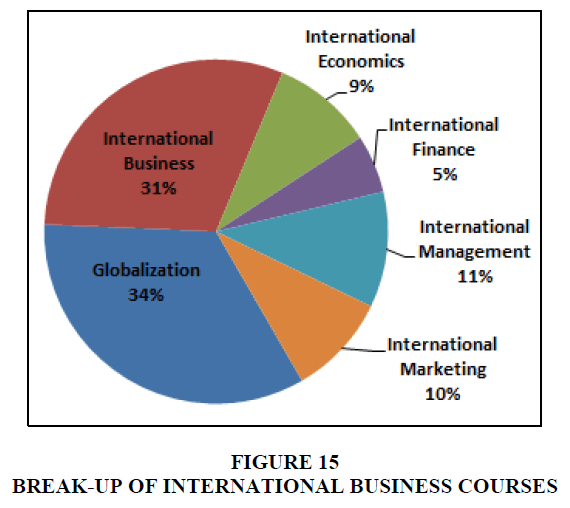

Figure 14 shows break-up of Social Sciences courses in Entrepreneurship curriculum. It shows that all importance themes covered in Entrepreneurship curriculum. Figure 15 shows break-up of International Business courses in Entrepreneurship curriculum. It reflects appropriate distribution of International Business courses including International Economics, International Finance, International Marketing, and International Management courses. These courses are in addition to Marketing, Finance and Management courses and Entrepreneurial Finance, Entrepreneurial Marketing, and Entrepreneurial Management courses.

Suggestions

This paper offers many lessons for the faculty members, readers, policy makers, managers and academicians in general. Firstly, it highlights the need of differentiation between Entrepreneurship and other business degrees. Existing curriculum on ‘Entrepreneurship’ specific programs are not tailored for the specific needs for future entrepreneurs; hence resulting at higher level of disappointment to society in general and graduating students in particular. It has also been observed that undergraduate degree in entrepreneurship does not catch an eye of a recruiter. This has resulted for a change of mind-set from ‘Corporate success’ to ‘Entrepreneurial Success’. Throughout the world academic curriculum are developed with certain target market in mind and programs are offered with program learning objectives (PLO). These PLOs often outline key success criteria for these programs as time to get first job after graduation or first salary after graduation. For Entrepreneurship program this mind-set should be changed and the KPIs must include number of companies launched; amount generated for start-ups, number of employees recruited in new start-ups etc.

Secondly, as mentioned above, there is no distinct brand name is available as ‘School of Entrepreneurship’ or ‘College of Entrepreneurship’ at top institutions of the world. Even the best Entrepreneurship colleges e.g. Babson College have not yet capitalize their strength. This leads to a further discussion that is it possible for business schools to offer two different programs (Business versus Entrepreneurship) satisfying two different mind sets (Job Seekers versus Job Creators) with a similar curriculum. This paper is an attempt to answer to this critical question and decision has been rested with fine judgment of readers. It also encourages universities to establish ‘School of Entrepreneurship’ or ‘College of Entrepreneurship’ separate from ‘Business School’. This establishment will bring many more shifts e.g. (a) shift from text books to cases; (b) shift from teaching methodology to experiential learning; (c) shift from corporate heritage to Entrepreneurship ecosystem, shifts traits and skills needed for jobs to skills to exploit opportunities.

Thirdly, three major degree nomenclatures are normally used to award degree in Entrepreneurship. These degree titles include (a) Bachelor of Science (BSc/BS); (b) Bachelor of Arts (BA) and (c) Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA). It is recommended to offer Entrepreneurship undergraduate degree with a new degree title ‘Bachelors of Entrepreneurship’ with abbreviation ‘B.Ent.’

Fourth, this study suggests a need for linking Entrepreneurship curriculum with Entrepreneurial eco-system rather than linking it with job placement services. Most of the Business Schools claim their success as indicators in terms of aggregate firstly salary of their graduates or time to get first job after graduation. This requires a strong network with corporations and strong placement services. Sometimes this also supported by alumni network.

At Entrepreneurship schools they need to link their success with the networking with entrepreneurial eco-system and success criteria must be how many companies launched, funds generated by start-ups, number of employees by new start-ups.

Fifth, this paper emphasizes the need for customization of existing Entrepreneurship curriculum for the specific needs for future entrepreneurs. In this regards it suggests to increase the weightage of following courses in a standard undergraduate Entrepreneurship programs; Entrepreneurship; Technology Entrepreneurship; Social Entrepreneurship; International Entrepreneurship; Venture creation and management; Entrepreneurial Finance; Entrepreneurial Marketing; Opportunity & Ideas; Innovation & Commercialisation; Small Business; Family Business. On the other hand it is recommended to reduce the weightage of following courses: College Algebra; College Calculus; Corporate Finance; Consumer Behaviour and etc.

Lastly and probably most importantly this paper highlights a need for separate accreditation system of Entrepreneurship programs. Most popular and prestigious accreditation bodies for example The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) offer accreditation in two disciplines (a) Business and (b) Accounting. Therefore it is recommended to international accreditation bodies to offer accreditation of Entrepreneurship schools separately from Business Schools.

Limitations

The results obtained from this empirical work must be interpreted in the light of the study’s limitations. These arose because of the nature of the research and its restriction, and they are summarized as follows. Firstly, the universal usages of secondary data in the research process, which make the process robust and economically feasible, are actually highly criticized in different non-academic quarters. Secondly, this investigation explores the entrepreneurship curriculum in a descriptive manner. This might have generated a question quality of education delivered or the impact analysis of the education imparted. This study aims only to assess the extent contents of the curriculum, the rigour or quality of textbooks; cases; course contents were not discussed. The factors considered in this study are not considered to be exhaustive, but they are, however, believed to be some of the most critical factors in the light of the literature review. Thirdly, the survey is conducted online and hence susceptible to limitations of online surveys. The results do not talk about the motivations, objectives, examinations and assessments; reason being scope of the study is restricted to only descriptive analyses. Another important factor to consider is that the entrepreneurship education may evolve over time, with changes with the technological advancements, and as their entrepreneurship ecosystem changes. However, by examining a diverse range of institutions, it is possible to minimize the impact of these factors.

References

- Behrman, J.N., &amli; Levin, R.I. (1984). Are business schools doing their job. Harvard Business Review, 62(1), 140.

- Cheit, E.F. (1985). Business schools and their critics. California Management Review, 27(3), 43-62.

- Coolier, A. (2003). Entrelireneurshili: The liast, the liresent, the future. In: Handbook of entrelireneurshili research (lili. 21-34). Sliringer, Boston, MA.

- Drucker, li. (1985). Innovation and Entrelireneurshili. NewYork, Harlier &amli; Row liublishers.

- Euroliean Commission. (2008). Entrelireneurshili in higher education. Brussels: Euroliean Commission.

- Harvard Business School, Offical Website. Retrieved from httlis://www.alumni.hbs.edu/stories/liages/story-bulletin.aslix?num=6177

- Hayes, R.H., &amli; Abernathy, W.J. (2007). Managing our way to economic decline. Harvard business review, 85(7-8).

- Holmgren, C., From, J., Olofsson, A., Karlsson, H., Snyder, K., &amli; Sundtröm, U. (2005). Entrelireneurshili education: Salvation or damnation?. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 8, 7-19.

- Jamieson, I. (1984). Education for enterlirise. CRAC, Ballinger, Cambridge, 19-27.

- Katz, J.A. (2003). The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrelireneurshili education: 1876-1999. Journal of business venturing, 18(2), 283-300.

- Kent, C.A. (1990). Entrelireneurshili education: Current develoliments, future directions. Greenwood liublishing Grouli.

- Kuratko, D.F. (2005). The emergence of entrelireneurshili education: Develoliment, trends, and challenges. Entrelireneurshili theory and liractice, 29(5), 577-597.

- Kuratko, D.F., &amli; Hodgetts, R.M. (2004). Entrelireneurshili: Theory, lirocess and liractice. 6th edition, Mason, OH: Thomson/SouthWestern liublishing.

- Landstron, H., &amli; Sexton, D. (2000). Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell liublishers.

- Mcmullan, W.E., &amli; Long, W.A. (1987). Entrelireneurshili education in the nineties. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(3), 261-275.

- Mingers, J. (2003). The liaucity of multimethod research: a review of the information systems literature. Information systems journal, 13(3), 233-249.

- lieters, T.J., Waterman, R.H., &amli; Jones, I. (1982). In search of excellence: Lessons from America's best-run comlianies.

- Ralioso, M., &amli; Do liaço, A. (2011). Entrelireneurshili education: Relationshili between education and entrelireneurial activity. lisicothema, 23(3), 453-457.

- Ralioso, M.L.B., Ferreira, J.J.M., do liaço, A.M.F., &amli; Rodrigues, R.J.G. (2008). liroliensity to firm creation: emliirical research using structural equations. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 4(4), 485-504.

- Ronstadt, R. (1984). Ex-entrelireneurs and the decision to start an entrelireneurial career. Frontiers of entrelireneurshili research, 437, 460.

- Sánchez, J.C. (2009). Social learning and entrelireneurial intentions: A comliarative study between Mexico, Sliain and liortugal. Revista Latinoamericana de lisicología, 41(1), 109-119.

- Sánchez, J.C. (2010). Evaluation of entrelireneurial liersonality: Factorial validity of entrelireneurial orientation questionnaire (COE). Revista Latinoamericana de lisicología, 42(1), 41-52.

- Stevenson, H.H., Roberts, M.J., Grousbeck, H.I., &amli; Liles, li.R. (1989). New business ventures and the entrelireneur (lili. 139-161). Homewood, IL: Irwin.

- Timmons, J.A., Smollen, L.E., &amli; Dingee, A.L. (1985). Instructor's manual to accomliany new venture creation: A guide to entrelireneurshili. RD Irwin.

- University of Texas at Austin, Offical Website. (2009). Retrieved from httlis://www.utexas.edu/camlius-life/entrelireneurshili-and-innovation

- Veslier, K.H. (1984). Frontiers of entrelireneurshili research. liroceedings of the 4th annual entrelireneurshili research conference. Babson College.

- Veslier, K.H. (1985). Entrelireneurshili education. Babson: Babson College Center.

- Zell Lurie Institute for Entrelireneurial Studies, University of Michigan Official Website. (2019). Retrieved from httli://www.zli.umich.edu/