Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 6S

A causal relationship model of self forgiveness among Thai youth offenders

Phummaret Phupha, Chulalongkorn University

Arunya Tuicomepee, Chulalongkorn University

Abstract

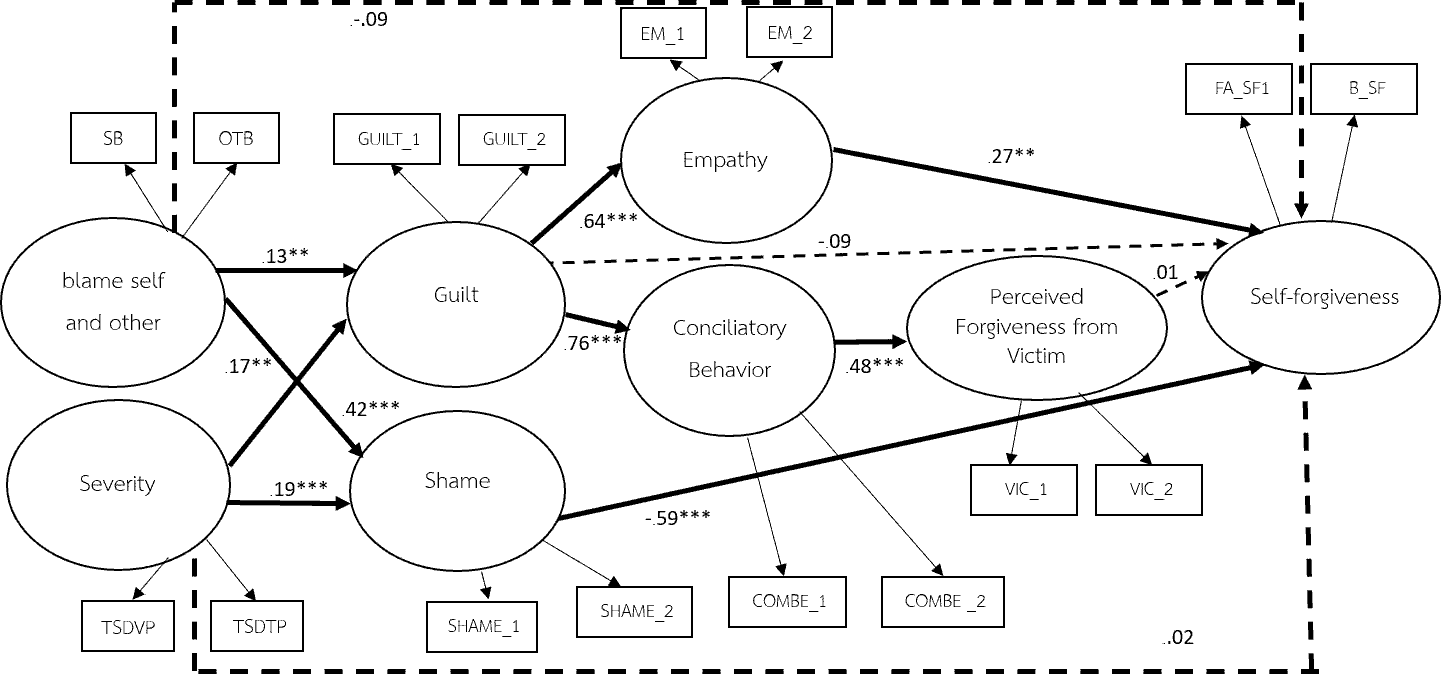

Self-forgiveness is the reduction of negative emotions that occurs when persons admit their wrongdoing and modify new thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Therefore, the objective of this research was to study the causal relationship model of self-forgiveness among youth offenders that consisted of seven important variables, namely blaming themselves and others, perceiving the severity of the offense, guilt, shame, empathy, conciliatory behaviors, and perceiving the forgiveness from the victims and those affected. The research sample group consisted of 1,031 juvenile offenders who were detained in juvenile detention and protection centers and training centers for children and youth with an average age of 17.42 +1.63 years. The results revealed that the causal model of self-forgiveness among juvenile offenders was consistent with the empirical data (Chi-square = 68.84, df = 53, p = 0.071, GFI = 0.992, AGFI = 0.979, RMR = 0.0257, RMSEA = 0.0170). All variables described the self-forgiveness variance for 41%. The factors that had the greatest overall influence on self-forgiveness were shame, empathetic understanding, and tendency to blame themselves and others, respectively. The shame and mutual understanding had direct influence on self-forgiveness. The tendency to blame oneself and others and to be guilty indirectly influenced the self-forgiveness. The findings suggested that self-forgiving youth offenders should focus on reducing feelings of shame, reducing the tendency to blame themselves and others. This included properly addressing guilt along with having a conscientious understanding of the victims and those affected leading to a “sincere apology”, showing responsible for wrongdoing until finally forgiving.

Keywords

Self-Forgiveness, Juvenile Offenders, Verification on Causal Model

Introduction

For the juvenile offenders , whether it is an offense that causes damage and harm to others, such as offenses related to property offenses about life, sexual offenses or offenses that cause damage and harm to oneself, such as drug-related offenses, the consequences of these offenses directly affect the youth offenders in their expressed thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, such as feeling ashamed, feelings of guilt, anger, regret, and disappointment, etc. (Griffin et al., 2015; Hall & Fincham, 2008). From a psychological point of view, the psychologists and therapists such as O’Connor et al. (1999) states that the self-forgiveness is the correction or reduction of negative emotions (such as guilt, shame, anger, regret, and disappointment) that are manifestations of blaming or Self-Condemnation) of a person after infringement, violation, wrongdoing or bad behavior towards others (Worthington, 2013) and improves positive mood (Liu, 2021; Peterson et al., 2017; Roxas et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2017). Self-forgiveness occurs only when persons admit their wrongdoing and modify new thoughts, emotions, and behaviors such as understanding other people’s perspectives more, viewing themselves in a more positive way, being more compromising and friendly. The empirical research studies on self-forgiveness caused by offending others, such as (Hall & Fincham, 2005) indicate that self-forgiveness results from changes in motivation based on three factors; (1) Affective factors including feelings of guilt that cause sympathy for others and induces compromising behaviors such as apologizing, compensating, seeking forgiveness. This guilt is negatively associated with self-forgiveness. Conciliation and empathetic behavior are the transmission variables while shame is the negative self-image and low self-worth. The shame motivates people to respond by escaping and not forgiving themselves. (2) The social-cognitive factors) included the inference and perception of the cause of wrongdoing (Attribution) such as blaming themselves and others. The studies have shown that the more people blame themselves and others, the less self-forgiveness they have. (3) The Offense-Related factors included conciliatory behaviors, apologizing and compromising behaviors towards the victims to reduce the feelings of guilt about the wrongdoing. It leads to self-forgiveness to perceive the severity of the offense. The higher level of perception on severity of the offense is, the lower level of self- forgiveness will be.

In 2008, Hall and Fincham (2008) studied the self-forgiveness model among 148 undergraduate students who said they had offended the others by causing them to experience pain and guilt. This was the long-term study. The findings revealed that the self-forgiveness model changed in motivation from 3 to 4 factors separated behavioral factors such as Conciliatory behavior out of the original 3 factors, namely the Offense-Related factors such as perceived transgression severity. In this study, participants had an increase in self-forgiveness after 7 weeks. It was found that the increasing guilt over time resulted in less self-forgiveness. The findings from this study concluded that guilt was an important variable in self-forgiveness and important for restoring a person’s positive self-awareness. In addition, McConnell et al. (2012) developed the study of Hall and Fincham (2005, 2008) to examine the self-forgiveness model in 406 undergraduate students in the central United States. The self-forgiveness model consisted of six sub-factors; (1) Attribution, (2) severity of transgressions, (3) guilt, (4) shame, (5) conciliatory behavior, and (6) Perceived forgiveness from Victim. The study found that the severity of the offense, guilt, conciliatory behavior and Perceived forgiveness from Victim were important factors that affected the self-forgiveness. In addition, the study found that the Attribution, empathy, and shame correlated with the forgiveness at low level.

During the past period, the Thai justice system has brought the concept of reconciliation justice emphasizing the benefits that the victims will receive and giving the offender an opportunity to have a conscience of the offender and show responsibility by doing good deeds to compensate the victims. This leads to the conciliation, compensation, and forgiveness between offenders and victims. However, one past research gap is the causal relationship model of self-forgiveness in past studies. For example, the studies of (Hall & Fincham, 2005 & 2008; McConnell et al., 2012) described the self-forgiveness only in university students. Therefore, in this study, the concept of the studies of (Hall & Fincham, 2005 & 2008; McConnell et al., 2012) was applied to the youth offenders who cause damage and harm others or offend oneself. The knowledge and understanding of the causal relationship model of self-forgiveness among youth offenders will help expanding the understanding of the relationship of factors related to self-forgiveness among these youths which will lead to the guidelines for the design, treatment, correction and rehabilitation of youth offenders.

Research Method

This research study was the descriptive research and the research project was accredited by the Human Research Ethics Committee, United Institutions Group, Series 1, Chulalongkorn University (Project Code 260/62) with the following methods of conducting research.

The sample group consisted of 1,031 youth offenders with the average age of 17.42 + 1.63 years (minimum age was 15 while maximum age was 25). All youths were detained in 11 juvenile detention and protection centers and training centers of the children and youth distributed in five regions of Thailand. The majority of youths were males (85.6%). Most were drug-related offenses (75.4%), followed by property-related offenses (7.3%). The number of offenses was 1.40+ 0.80 times (the lowest number was 1 time, the highest number was 11 times). The youth live with their parents (41.6%), live with one parent (25.6%), live with relatives (grandparents, grandmothers, uncles, aunts) (25.4%). All youths are voluntary to participate in the research.

The research tools consisted of general information questions (such as gender, age, current highest level of education, offense type, length of time for legal proceedings (since the date of arrest), number of offenses, persons with whom the youth lived) and the scales were as follows:

1) For the scales of self-forgiveness, the researchers developed from the State Self-Forgiveness Scale developed by Wohl et al. (2008). This scale is the scale that allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5-point scale (1 means strongly disagree and 5 means strongly agree). The accuracy of scales in this research was .88.

2) For the scales of blaming oneself and others, the researchers developed from the Multidimensional Forgiveness Inventory of Tangney et al. (2002). This scale allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5- point scale (1 means they are not likely to think that way and 5 means they are most likely to think that way). The accuracy of scales in blaming oneself and others in this research was .88 and .84,

3) For the scales of perceived severity of wrongdoing, the researchers developed from the Transgression Semantic Differentiation (TSD) of McConnell et al. (2012). This measure provides respondents a seven- level self-assessment scale (1 means mild and severe or 1 means harmless and 7 means the most dangerous). The accuracy of scales in this research was .92.

4) For the scales of guilt, the researchers developed from the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS) by Marschall et al. (1994). This scale allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5-point scale (1 means not at all and 5 means the most accurate). The accuracy of scales in this research was .84.

5) For the scales of shame, the researchers developed from the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS) by Marschall et al. (1994). This scale allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5-point scale (1 means not at all and 5 means the most accurate). The accuracy of scales in this research was .87.

6) For the scales of empathy, the researchers developed from the scales of Interpersonal Reactivity Index of Davis (1983). This scale allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5-point scale (1 means not at all and 5 means the most accurate). The accuracy of scales in this research was .86.

7) For the scales of conciliatory behavior, the researchers developed from the Conciliatory Behaviors Scale (CBS) of (McCullough et al., 1997). This scale allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5-point scale (1 means not at all and 5 means the most accurate). The accuracy of scales in this research was .90.

8) For the scales of perceived forgiveness from victims and suffered persons, the researchers developed from the Heartland Forgiveness Scale of Thompson et al., 2005 developed from (McConnell et al., 2012). This scale allows respondents to assess themselves on a 5-point scale (1 means not at all and 5 means the most accurate). The accuracy of scales in this research was .88.

Data Collection

The researchers asked for assistance to collect research data from the Department of Juvenile Observation and Protection. The researchers then coordinated with the psychologists, social workers, officers of the Department of Juvenile Observation and Protection, Child and Youth Training Centers for initial screening. Subsequently, the researchers requested an appointment to meet with the youth who passed the screening and expressed their intention to participate in the project to have them answer the questionnaire 1 time in approximately 45 minutes. The researchers had the approach to prevent the leakage of information on criminal offense and other personal information of youth. The researchers collected all data manually. In addition, the questionnaires did not collect the names and personal information of the youth. The survey responses were conducted at the Child and Youth Observation and Protection Center and the Child and Youth Training Center (If the youth was unable to read the questionnaire by themselves, the researchers read them one by one until they were complete). After collecting the questionnaire, the researchers immediately put it in the sealed envelope. Finally, the questionnaire data was analyzed and the research data was presented entirely. The names and personal information of the youth were kept secret, confidential and there was no information that could identify the identity of the respondents.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by using the Structural Equation Method with Lisrell Program (LISSREL).

Research Findings

The causal model of self-forgiveness among youth offenders in this study had important variables; blaming oneself and others, perceived the severity of the offense, guilt, shame, empathy, conciliatory behavior and perceived forgiveness from the victims and those affected. The self-forgiveness model of youth offenders was consistent with the empirical data (Chi-square = 68.84, df = 53, p = 0.071, GFI = 0.992, AGFI = 0.979, RMR = 0.0257, RMSEA = 0.0170). All variables in the equation could explain the remission variance. For the four main factors affecting self-forgiveness among youth offenders, it was found that the first factor was perceived severity of the offense. It was found that there was neither direct nor indirect influence on the self-forgiveness of the youth offenders. The second factor was the inference and realization of offense (blaming oneself and others). It was found that blaming oneself and others had statistically significant influence on self-forgiveness (Indirect influence was -.09, p < .001. Total influence was -.18, p < .001) in 2 paths. Path 1: Blaming oneself and others results in self-forgiveness through guilt and empathetic understanding. When the youth offenders blame themselves and others more, they feel more guilt. This growing sense of guilt will bring youth to perspective of the victims with more conscientious understanding. Path 2: Blaming oneself and others results in self-forgiveness through shame. When the youth offenders blame themselves and others more, they become more ashamed. This increase in shame leads to a decrease in their self-forgiveness. The 3rd factor is the emotion (guilt and shame). It was found that guilt had significantly positive indirect influence on self-forgiveness through empathy (Influence value of .17, p < .001). The shame had negative direct influence on self-forgiveness of the youth offenders with statistical significance (Influence value of -.59, p < .001). The consensual understanding had statistically significant low positive direct influence on self- forgiveness (Influence value of .26, p < .001). The 4th factor 4 is Compromise behavior and perception of forgiveness from victims and affected people on self-forgiveness of youth offenders. The results of this research found no influence of conciliatory behavior and perceived forgiveness from the victims and those affected with statistically significant self-forgiveness among youth offenders.

Chi-square = 68.84, df =53, p = 0.071, GFI = 0.992, AGFI = 0.979, RMR = 0.0257, RMSEA = 0.0170

| Table 1 Parameter Estimate and Statistical Value in Testing the Causal Relationship Model for Self-Forgiveness Among Thai Youth Offenders (N= 1,031) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Causal variable ⇒ Result variable | Parameter | SEb | t |

| Matrix GA (Gamma) | |||

| Likeliness in blaming oneself and others → Guilt | 0.13 | 0.04 | 2.74** |

| Likeliness in blaming oneself and others → Shame | 0.17 | 0.05 | 3.24** |

| Likeliness in blaming oneself and others → Self-forgiveness | -0.09 | 0.05 | -1.60 |

| Perceived Severity of Offense → Guilt | 0.42 | 0.04 | 8.73** |

| Perceived Severity of Offense → Shame | 0.18 | 0.05 | 3.44** |

| Perceived Severity of Offense → Self-forgiveness | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.42 |

| Matrix BE (Beta) | |||

| Guilt → Conciliatory behavior | 0.76 | 0.07 | 10.47** |

| Guilt → Empathy | 0.64 | 0.07 | 8.40** |

| Guilt → Self-forgiveness | -0.09 | 0.11 | -0.82 |

| Shame → Self-forgiveness | -0.59 | 0.06 | -8.75** |

| Conciliatory behavior → Perceived forgiveness from thevictims and those affected | 0.47 | 0.05 | 8.74** |

| Empathy → Self-forgiveness | 0.26 | 0.10 | 2.70** |

| Perceived forgiveness from the victims and those affected→Self-forgiveness | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

=

| Table 2 Results of Analysis on Direct Effects, Indirect Effects, Total Effects and Results of the Self-Forgiveness Straightness Model Analysis (N = 1,031) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result variabl es | Statist ics | Causal variables | |||||||||||||||||||||

| OBSB | SEV | GUILT | SHAME | CON | EMPATHY | VIC | R2 | ||||||||||||||||

| DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | |||

| GUIL T | b | 0.1 | - | 0.13 | 0.4 | - | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.2 |

| SE | 0 | - | 0.04 | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| t | 2.74** | - | 2.74** | 8.73** | - | 8.73** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SC | 0.1 | - | 0.13 | 0.4 | - | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SHA ME | b | 0.2 | - | 0.17 | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 |

| SE | 0.1 | - | 0.05 | 0.1 | - | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| t | 3.24 ** | - | 3.24 ** | 3.44 ** | - | 3.44 ** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SC | 0.2 | - | 0.17 | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| CON | b | - | 0.0 9 | 0.09 | - | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | - | 0.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 |

| SE | - | 0.0 3 | 0.03 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| t | - | 2.7 2* * | 2.72 ** | - | 8.1 2* * | 8.12 ** | 10. 47 ** | - | 10. 47 ** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SC | - | 0.09 | 0.09 | - | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | - | 0.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| EMPA THY | b | - |

0.0 8 |

0.08 | - | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | - | 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.4 |

| SE | - | 0.0 | 0.03 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| t | - | 2.6 9** | 2.69** | - | 7.3 0** | 7.30** | 8.4 0** | - | 8.4 0** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SC | - | 0.08 | 0.08 | - | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | - | 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| VIC | b | - | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | 0 | 0.2 | - | 0.4 | 0.4 | - | - | - | 0.47 | - | 0.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.2 |

| SE | - | 0.01 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0.1 | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| t | - | 2.6 1** | 2.61** | - | 6.1 3** | 6.13** | - | 6.8 7** | 6.8 7** | - | - | - | 8.7 4** | - | 8.7 4** | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SC | - | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | 0 | 0.2 | - | 0.4 | 0.4 | - | - | - | 0.47 | - | 0.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| SF | b | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0 | -0 | -0 | -0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | - 0.59 | - | -1 | - | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0.4 |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.06 | - | 0.1 | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | ||

| SF | -1.6 | - 2.7 7** | - 3.31** | 0.4 | -2 | -1 | -1 | 2.45* | 1.2 | - 8.7 5** | - | - 8.7 5** | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.7 0** | - | 2.7 0** | 0.2 | - | 0.2 | ||

| SC | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0 | -0 | -0 | -0 | 0.2 | -0.1 | - 0.59 | - | -1 | - | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | ||

Remark: DE = Direct Effects, IE = Indirect Effects, TE = Total Effects. The figure in the 1st row is the Coefficient (b). The figure in the 2nd row is the Standard Error (SE). The figure in the 3rd row is the t-statistics (t). The figure in the 4th row is the completely standardized solution (SC) ***p < .001, simple tag. **p < .01, simple tag. ***p < .05, simple tag.

Conclusion and Discussion

The findings from this study can be discussed based on the condition factor group proposed by Hall and Fincham (2005, 2008) and the study by McConnell et al. (2012) in the following four factor groups:

1st Factor: The offense-related variables is the perceived transgression severity on the self-forgiveness among the youth offenders. This research findings reflected correlational stereotypes of perceiving the severity of offenses affecting youth offenders’ self-forgiveness through the same pathways found in the studies of (Hall & Fincham, 2008; McConnell et al., 2012). Perceived severity of wrongdoing is an important variable affecting self-forgiveness. However, in this study, the role of perceiving the severity of the offense did not affect the youth offender’s self-forgiveness statistically. One possibility that the results of this study found no influence of the perceived severity factor of wrongdoing that affects self-forgiveness is possibly the youth offenders. 21.7% of the sample group were enrolled in the training in a juvenile detention and protection facility or had been in the training at the Child and Youth Training Center for 7-12 months. 31.5% had been trained in the Child and Youth Observation and Protection Center for more than 1 year. It is therefore possible that self-reporting by recalling the severity of the offense situation in a long past event may be inaccurate compared to studying the event or situation that has just occurred. Another possibility is most youths have drug- related offenses such as drug abuse or trafficking (75.4%) which may result in perceived levels of violence that differ from other offenses such as theft or assault. Others (7.1%) whose

perceived severity of the offense affects self-forgiveness based on the duration of the offense and the type of offense may be further investigated with empirical research.

2nd Factor: The social-cognitive factor is to blame oneself and others. The past studies have indicated that blaming oneself and others is the Attribution of unadjusted individuals. Romero et al. (2006) found that offenders who do not forgive themselves tend to have inferences and perceptions of the cause of their offence. In this regard, Hall and Fincham (2005) further explained that inferences and perceptions of the causes of wrongdoing in blaming oneself and others also influence emotional responses, such as guilt, by individuals with inferences and perceptions of the cause of non-adaptive wrongdoing. They often have greater sense of guilt and seek forgiveness. This directly and indirectly affects self-forgiveness. They also resulted in increased feelings of guilt and shame (Fisher & Exline, 2006; Hall & Fincham, 2005; Tangney et al., 2002). In this study, it was reflected that blaming oneself and others of the young offenders does not always lead to self-forgiveness. The influence of blaming oneself and others of youth offenders in the 3 paths have different effects on self-forgiveness. The first path is to infer and recognize the cause of wrongdoing by blaming oneself and others. It has a positive effect on the youth offenders’ self-forgiveness through increasing guilt, creating a change in motivation to understand the victim or perceiving the victim’s perspective with a more empathetic understanding. This will lead to the increasing self-forgiveness. At the same time, on the second path, the increasing guilt will lead to more conciliatory behavior among young people, the increasing awareness of forgiveness from the victims and those affected. However, on this path, the effects of forgiveness from victims and those affected was low and did not significantly affect the youth offenders’ self-forgiveness. The third path is the inference and recognition of the cause of wrongdoing by blaming oneself and others negatively affecting the self-forgiveness of the youth offenders through the growing shame. The youth had statistically significant reduction in self-forgiveness. It can be seen that in this study, young people with inferences and perceptions of the cause of wrongdoing shows lack of adaptation, e.g. blaming oneself and others. It is followed by the feeling of guilt helping youth with self- blame and high guilt. The perspective and conscientious understanding of the victims have been increased to reduce the shame. This will lead to an increase in the youth’s self-forgiveness level. 3rd Factor: The emotions including guilt, shame, empathy, and self-forgiveness among young offenders. Regarding the guilt, although the past studies have reported that guilt has negative influence on self-forgiveness that when offenders have a higher sense of guilt, they have a lower self- forgiveness. The results of this research give a picture that the guilt of youth offenders can help increasing the level of self-forgiveness of young offenders. These findings support the study of McConnell et al. (2012) that examined the Hall and Fincham (2005) self-forgiveness theoretical model. In the study of McConnell et al. (2012), the behavioral variables were proposed additionally to the Hall and Fincham (2005) self-forgiveness theoretical model and the Hall and Fincham (2008) empirical study. The victim’s seeking forgiveness and perceived forgiveness variables from the sacred has positive effect on forgiveness of offenders. Regarding the shame, in this study, the shame was found to have negative direct influence on the self-forgiveness of youth offenders. The youth with a high level of shame had low level of self-forgiveness. Hall and Fincham (2005) explained that negative feelings, such as shame, were part of the response to the wrongdoings and mistakes of others to punish, blame, or condemn oneself. The offenders who have severely condemned themselves often have a high tendency to be ashamed resulting in low self-worth and avoiding involvement in connection with recalling their past actions and ultimately. This results in the non-forgiveness of oneself. In this study, it was found that Empathy has a low, direct, positive influence on self-forgiveness with statistical significance. When the youth offenders had higher level of empathy, it also resulted in greater self-forgiveness. Although the results of the research are different from those of Romero et al. and when there is a higher level of self-forgiveness reporting lower levels of guilt and empathy, an explanation that empathy influence on self-forgiveness of youth offenders at low level may be due to the fact that 75.4% of the sample in the study were youth offenders who were drug addicts or traffickers. One observation of offenses in the case of drug abuse or trafficking is that the offense is the one without the obvious litigant, victim, or suffered person compared to sex-harassment cases or physical assault cases. Given the peculiarities of guilt bases in which there are no clear parties, it may be possible that consensual understanding in the youth offenders sampled in this study had a low influence on their self-forgiveness. The possibilities and conclusions in this regard should be further examined with empirical evidence.

4th Factor: The behaviors such as conciliatory behavior and Perceived forgiveness from Victim influenced the self-forgiveness of the youth offenders. The results of this research found no influence of conciliatory behavior and Perceived forgiveness from Victim and those affected with the self-forgiveness of youth offenders. The first possibility of the findings may be that conciliatory behavior may not occur naturally. It takes a therapeutic, remedial process that facilitates that process. Hall and Fincham (2008) examined the self-forgiveness of undergraduate students who identified themselves as causing pain and regret to others over the past three days with feeling guilty about what they had done and want to deal with the situation in a new way by participating in the self-transformation process and taking 7 different variables assessments. The study results found that in the first assessment, conciliatory behavior, such as apologizing, trying to improve the situation, affecting the victim found to have no effect on self- forgiveness. However, when the students participated in the self-transformation process in the subsequent assessment, the influence of the conciliatory behavior was found on the injured person with statistically significant effect on self-forgiveness. It can be seen that the conciliatory behavior of youth is an important variable only when used in conjunction with the youth rehabilitation process by allowing the youth to apologize, correct, or compensate for wrongdoing.

The findings of the study provide a clearer picture of the correlation patterns of variables in the motivation-shifting process leading to forgiveness that are specific to the context of the youth offenders. The important issues are such as the youth with inference and inadequate recognition of the causes of wrongdoing, e.g. blaming oneself and others, have a feeling of guilt. If there is a rehabilitation process that allows youth who blames himself and others and high guilt to gain a consensual perspective and understanding of the victim and to reduce shame, it will lead to an increase in the level of self-forgiveness of youth to be higher. The preparation of psychologists and personnel acting in rehabilitation of youth offenders in relation to factors for self-forgiveness of youth in the aforementioned issues will make the process of justice reconciliation with an apology process or expression which compromise behavior is more effective. However, due to the results of the causal model study demonstrating the understanding, the causal overview of factors affecting the self-harm of youth offenders includes all bases of crimes. Future studies may consider additional causal model analysis of self-forgiveness among different crime base groups. This will show whether the differences in the influence of factors affecting self-forgiveness are statistically significant or not for young people. This may have different influences on self-forgiveness. Analysis using gender variables as diacritics will be able to better explain the influence of factors related to self-forgiveness and be more relevant to the sample. It leads to an understanding and awareness of those involved in the healing process and can lead to the creation of appropriate policy guidelines with the nature of offense both male and female youth more efficiently and appropriately.

Acknowledgment

This article is part of a Ph.D. research project, Department of Counseling Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Chulalongkorn University. The researchers received a scholarship to study from Scholarship for Doctoral Program “100 Years of Chulalongkorn University” for the first semester of the academic year 2017 for 3 years and “Thesis Grant for students”, Graduate School Chulalongkorn University.

References

- Davis, M.H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach.

- Journal of personality and social psychology, 44(1), 113.

- Fisher, M.L., & Exline, J.J. (2006). Self-forgiveness versus excusing: The roles of remorse, effort, and acceptance of responsibility. Self and Identity, 5(02), 127-146.

- Griffin, B.J., Worthington Jr, E.L., Lavelock, C.R., Greer, C.L., Lin, Y., Davis, D.E., & Hook, J. N. (2015). Efficacy of a self-forgiveness workbook: A randomized controlled trial with interpersonal offenders. Journal of counseling psychology, 62(2), 124.

- Hall, J.H., & Fincham, F.D. (2005). Self–forgiveness: The stepchild of forgiveness research. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 24(5), 621-637.

- Hall, J.H., & Fincham, F.D. (2008). The temporal course of self–forgiveness. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 27(2), 174-202.

- Liu, J. (2021). Social support mediates the effect of forgiveness on subjective wellbeing in college students. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 49(5), 1-9.

- Marschall, D., Sanftner, J., & Tangney, J. (1994). The state shame and guilt scale (SSGS) George Mason University. Fairfax, VA.

- McConnell, J.M., Dixon, D.N., & Finch, W.H. (2012). An alternative model of self-forgiveness. The New School Psychology Bulletin, 9(2), 35-51.

- McCullough, M.E., Worthington Jr, E.L., & Rachal, K.C. (1997). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships.

- Journal of personality and social psychology, 73(2), 321.

- O'Connor, L.E., Berry, J.W., & Weiss, J. (1999). Interpersonal guilt, shame, and psychological problems. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 18(2), 181-203.

- Peterson, S.J., Van Tongeren, D.R., Womack, S.D., Hook, J.N., Davis, D.E., & Griffin, B.J. (2017). The benefits of self-forgiveness on mental health: Evidence from correlational and experimental research. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(2), 159-168.

- Romero, C., Friedman, L.C., Kalidas, M., Elledge, R., Chang, J., & Liscum, K.R. (2006). Self-forgiveness, spirituality, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(1), 29-36.

- Roxas, M.M., David, A.P., & Aruta, J.J.B.R. (2019). Compassion, forgiveness and subjective well-being among filipino counseling professionals. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 41(2), 272- 283.

- Tangney, J., Boone, A., Dearing, R., & Reinsmith, C. (2002). Individual differences in the propensity to forgive: Measurement and implications for psychological and social adjustment. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Thompson, L.Y., Snyder, C.R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S.T., Rasmussen, H.N., Billings, L.S., Heinze, L., Neufeld, J.E., Shorey, H.S., & Roberts, J.C. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of personality, 73(2), 313-360.

- Worthington, E.L. (2013). Self-condemnation and self-forgiveness. Bibliotheca sacra, 170(680), 387-399.

- Yao, S., Chen, J., Yu, X., & Sang, J. (2017). Mediator roles of interpersonal forgiveness and self-forgiveness between self-esteem and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 36(3), 585-592.