Research Article: 2018 Vol: 17 Issue: 5

A Systems Thinking on Developing Holistic Well-Being among Youth

Jeffrey Lawrence D’silva, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Nor Aini Mohamed, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Hayrol Azril Mohamed Shaffril, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Abstract

There is much deliberation on the concept of well-being and as well as the appropriate mechanism to measure holistic well-being. This study attempts to use a systems thinking approach to develop a youth holistic well-being by constructing a causal map encompassing domains that contribute towards Malaysian youth well-being. The results depict the balancing and reinforcing loops that would enable resources to be used effectively and efficiently to achieve the mission of elevating youth holistic well-being.

Keywords

Casual Relationship, Holistic Well-Being, Systems Thinking, Youth.

Introduction

Well-being continuous to garner interests among researchers and policy-makers as it is deemed fundamental to human happiness (D’Silva, 2017). Historically during the period of Aristotle, individuals’ progress to acquire knowledge and skills, income, social bonding, and health is closely related to well-being. Then came an era of classical economists that emphasized the importance of wealth on well-being and happiness. However, arguments continue to exist on just equalling individual happiness with national income (Easterlin, 2001; Cummins et al., 2003; Sen, 1987). Thus, more researchers began to examine the possible domains that contribute towards well-being from the perspective of economy, psychology, sociology and public policy. In this process, it generated a number of terms namely quality of life, happiness, objective wellbeing and subjective well-being (Diaz & Bui, 2017). Well-being has been divided into two approaches, namely the objective and subjective approaches (Western & Tomaszewski, 2016), and because it is believed that an individual’s subjective evaluation of their emotions and quality of life is important as it reflects their position on their objective achievement. Lately, the concept of holistic well-being is being advocated as a means to measure well-being whereby it combines both objective and subjective well-being indicators (Forgeard et al., 2011). Another important element in the process of measuring well-being is the use of systems thinking and complexity science and a recent study by Rusoja et al. (2018) highlighted the importance of systems thinking to improve the execution of the Sustainable Development Goals. This study is an initial attempt to apply a systems thinking mechanism by using causal maps to depict the dimensions that could elevate youth holistic well-being.

Youth Well-Being

Youth undoubtedly is considered as a significant group in the world as they possess the creativity, potential, and capacity for changes to happen (UNESCO, 2018). UNESCO describes youth as the transition period between the over-dependence period of childhood and the independent period of adulthood. The age-range of youth varies according to countries whereby it could range from 15 to 35 years. Youth face a myriad of problems beginning from education right up to employment and thus the well-being of youth is paramount in the quest for sustainable development. There are a number of indicators used to measure youth well-being. For instance, the Global Youth Well-being Index encompasses seven dimensions, namely, economic, education, health, safety & security, information & communication technology, gender equality, and citizen participation (Sharma, 2017). On the other hand, the Malaysian Youth Index has 12 indicators to measure well-being. This study is intended to identify contributing factors on the holistic well-being of youth with the spatial range based on their current location.

Literature Review

Previous literature shows that there is a multidimensional linkage on the concept of wellbeing as it is placed together with other concepts like happiness, quality of life, life satisfaction, etc. Beginning from the hedonistic point of evaluating happiness, the research on well-being has been expanded to obtaining views from the economic, political and social dimensions. Another point revealed is that well-being can be linked to the objectivity and subjectivity indictors (Gasper, 2004). In objective well-being, it focuses on the needs whereas individual evaluation about life satisfaction constitutes subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1999; Tay et al., 2015). Some scholars argued that it is inappropriate to combine both this measurement of well-being. However, Forgeard et al. (2011) and Yassin et al. (2015) proclaimed that the complexities of well-being can be further understood if there is a mix of objective and subjective indicators. Thus, the study proposes the concept of holistic well-being taking into account the pivotal contributions of both the objective and subjective well-being domains.

The theoretical frameworks to comprehend the concept of well-being are focused on three main disciplines. Firstly, the Capability Approach by Sen (1987) states that well-being is firmly rooted in terms of what the people can do and can be, and the real opportunities that they have in their disposition. On the other hand, well-being, as suggested by Allardt (1973), is a system comprising three distinguished dimensions of needs: having (material conditions such as facilities), loving (social support) and being (personal growth) and it can have objective and subjective approaches in every dimension. Baker et al. (2004) see well-being as equality in terms of economic, working and education, cultural, political, and affective.

From the methodological perspective, previous studies focussed mainly on obtaining data using the quantitative approach and a few concentrated on qualitative research with mixed methods strategy. Globally some of the measurements that applied the quantitative indicators are the Human Development Index that constituted three dimensions of: (i) life expectancy, (ii) education achievement, and (iii) standard of living, OECD (2013) Better Life Index that had the domains of income, employment, housing, environment, education and skill, health, personal safety, social relationship, civic engagement, work-life balance, and subjective well-being, and Legatum Institute (2017) Prosperity Index that proposed economy, governance, social capital, education, health, safety and security, individual freedom, and entrepreneurship and opportunity as the domains of measurement. Undeniably, most of the previous studies on community wellbeing were carried out using the linear models (Rusoja et al., 2018). Only limited studies were carried out using the systems thinking approach to explain well-being in the context of interlinkage between variables and even then it is limited in the context of health well-being (Rosas & Knight, 2018). Thus, the theme of youth holistic well-being applying the systems thinking approach is novel and gives opportunities for policymakers to provide feasible solutions to enhance the well-being of youth.

Research Design

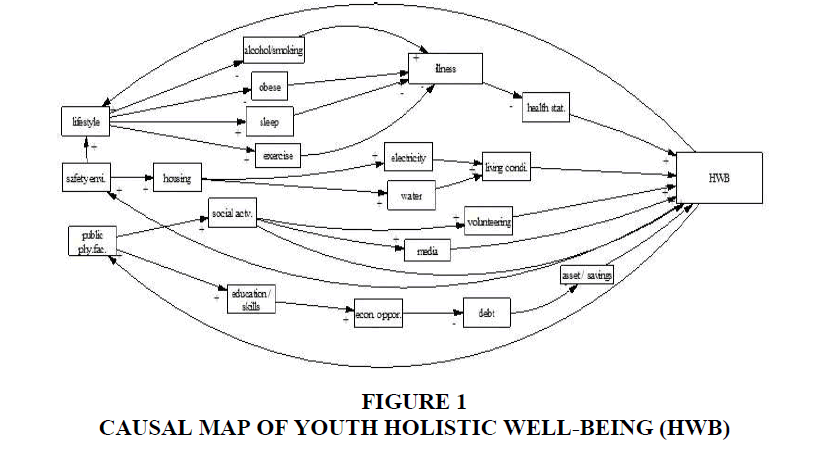

The study is designed using a systems thinking mechanism to identify the path and structure of interactions among the domains that affect youth holistic well-being. Thus, it evades the traditional forms of analysis that used either regression or structural equation modeling. It is believed that a systematic, causal and structural relationship method will help to better understand the direct and indirect effects of variables related to youth holistic well-being. Previous literature had identified a number of factors that contribute towards youth holistic wellbeing (Sharma, 2017). The variables as in Figure 1 are life-style (lifestyle), safety environment (safety envi.), public physical facilities (public phy.fac.), education/skills, economic opportunities (econ. oppor.), debt, asset/savings, housing, social activities (social actv.), media, volunteering, water, electricity, living conditions (living condi.), exercise, sleep, obese, alcohol/smoking, illness, and health status (health stat.).

Results

Figure 1 shows the causal map that depicts the overall relationships between the variables of youth holistic well-being. It is demonstrated using arrows and ‘+’ with ‘-’ signs. The ‘+’ sign shows a positive relationship while ‘-’ indicates a negative relationship. Jang et al. (2018) mentioned that the loop is a reinforcing loop if the number of ‘-’signs are even, and, if it is odd, the loop is a balancing loop.

Reinforcing Loop of Public Physical Facilities

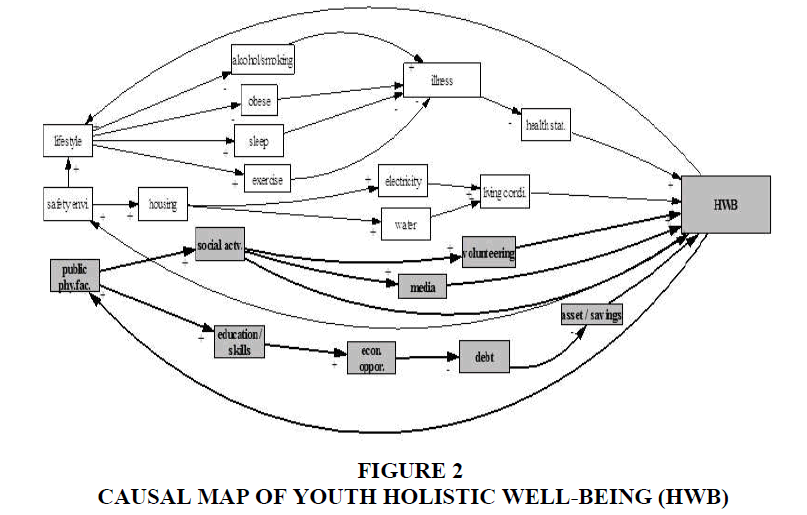

The loop of Public Physical Facilities (A & B) is being detailed out in Figure 2:

A1. More availability of public physical facilities will lead to greater social interactions.

A2. Greater social interactions will enhance youth usage of media and volunteerism.

A3. Wider usage of media and volunteerism will enhance the youth holistic well-being.

B1. More availability of public physical facilities will enable youth acquiring higher education and skills.

B2. The higher the education and skills acquired, the higher the economic opportunities will be.

B3. The greater the economic opportunities, the lesser the youth’s level of debt.

B4. The lesser the level of youth’s debt, the higher will be their asset and savings.

B5. The higher the youth’s asset and savings, the higher its holistic well-being will be.

Reinforcing Loop of Lifestyle

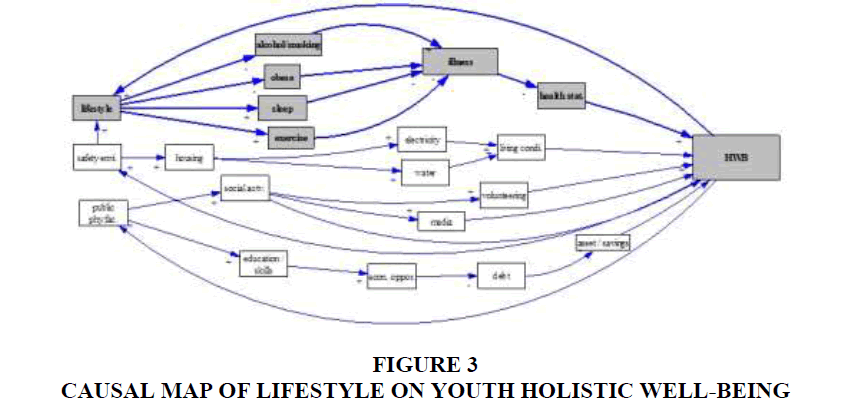

The loop of Lifestyle (C & D) is being detailed out in Figure 3:

C1: The better the lifestyle of youth, the lower will be the level of excessive smoking and drinking and obesity.

C2: The lower the level of excessive smoking and drinking and obesity, the lower will the number of youth facing illness.

C3: The lower the number of youth facing illness, the higher the level of health status will be.

C4: The higher the level of youth health, the higher its well-being will be.

D1: The better the lifestyle of youth, the higher will be the times spend on exercise and sleep.

D2: The higher the time youth spend on exercise and sleep, the lower will be the number of youth facing illness.

D3: The lower the number of youth facing illness, the higher the level of health status will be.

D4: The higher the level of youth health, the higher its well-being will be.

Balancing Loop of Safety Environment

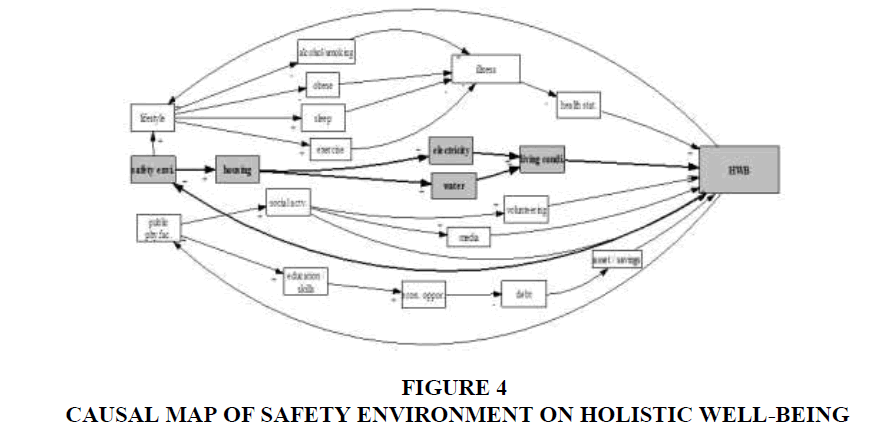

The loop of Safety Environment (E) is being explained in Figure 4:

E1: The greater the safety environment is, the larger will be its housing areas.

E2: The larger is the housing areas, the higher will be the providence of electricity and clean water for youth.

E3: The higher the providence of electricity and clean water for youth, the higher its living conditions will be.

E4: The higher the living conditions of youth, the higher its holistic well-being will be.

Conclusion

This study has endeavored to portray youth holistic well-being by developing a systems axiom to navigate domains affecting youth holistic well-being. The reinforcing and balancing loops can be used by the concerned parties to effectively utilize all the limited resources to accomplish the mission of the framework. It is proposed that more studies should be carried out utilizing the systems thinking mechanism to further elevate the level of youth holistic well-being.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Research Management Centre, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

References

- Allardt, E. (1973). About dimension of welfare: An explanatory analysis of the comparative Scandinavian survey. University of the Helsinki, Research Group of Comparative Sociology Research Reports.

- Baker, J., Lynch, K., Cantillon, S., & Walsh, J. (2004). Equality from theory to action. London: Palgrave.

- Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., Van Vugt, J., & Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: The Australian unity wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 64(2), 159-190.

- Diaz, T., & Bui, N. H. (2017). Subjective well-being in Mexican and Mexican American women: The role of acculturation, ethnic identity, gender roles, and perceived social support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(2), 607-624.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276.

- D’Silva, J.L. (2017). Well-being among Japanese retirees in Malaysia: Initial findings on subjective well-being. Proceedings from IPSAS Research Findings, Institute for Social Science Studies, UPM.

- Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111(473), 465-484.

- Forgeard, M. J., Jayawickreme, E., Kern, M. L., & Seligman, M. E. (2011). Doing the right thing: Measuring wellbeing for public policy. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1).

- Gasper, D. (2005). Subjective and objective well-being in relation to economic inputs: Puzzles and responses. Review of Social Economy, 63(2), 177-206.

- Jang, J., Lee, S. A., Kim, W., Choi, Y., & Park, E. C. (2018). Factors associated with mental health consultation in South Korea. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 17.

- Legatum Institute. (2017). Legatum prosperity index. Retrieved from: https://www.prosperity.com/

- OECD. (2013). How’s life? Measuring well-being. Retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/sdd/3013071e.pdf

- Rosas, S., & Knight, E. (2018). Evaluating a complex health promotion intervention: case application of three systems methods. Critical Public Health, 1-16.

- Rusoja, E., Haynie, D., Sievers, J., Mustafee, N., Nelson, F., Reynolds, M., Sarriot, E., Swanson, R.C., & Williams, B. (2018). Thinking about complexity in health: A systematic review of the key systems thinking and complexity ideas in health. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 600-606.

- Sen, A. K. (1987). Commodities and capabilities: Professor Dr. P. Hennipman lectures in economics, 1982 delivered at the University of Amsterdam. Oxford University Press.

- Sharma, R. (2017). Global youth well-being index. Retrieved from: https://www.youthindex.org/full-report

- Tay, L., Kuykendall, L., & Diener, E. (2015). Satisfaction and happiness the bright side of quality of life. In Global handbook of quality of life (pp. 839-853). Springer, Dordrecht.

- UNESCO. (2018). Learning to live together: Be youth, with youth, for youth. Retrieved from: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/youth/

- Yassin, S.M., Samah, A.A., D’Silva, J.L., Shaffril, H.A.M., & Sahharon H. (2015). Well-being revisited: A Malaysian perspective, poverty eradication foundation. Selangor.

- Western, M., & Tomaszewski, W. (2016). Subjective wellbeing, objective wellbeing and inequality in Australia. PloS one, 11(10).