Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Application of Maqasid Al-Shariah into Supply Chain Management Practices for Sustainable Development

Eley Suzana Kasim, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Negeri Sembilan, Kampus Seremban & Accounting Research Institute (ARI) Universiti Teknologi MARA

Dalila Daud, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Negeri Sembilan

Md. Mahmudul Alam, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Normah Omar, Accounting Research Institute (ARI) Universiti Teknologi MARA

Elisa Kusrini, Islamic University of Indonesia

Abstract

The study aimed to provide additional insights on how supply chain management practices are used to promote sustainable development in line with Maqasid Al-Shariah principles of Islam. A multiple case study approach involving two major automotive firms in Malaysia was used to address key research issues. The results show that these SCM practices, viz. resources, information, integration, and relationship practices support the promotion of Maslahah for all human beings which is consistent with the aims of Maqasid Al-Shariah principles for sustainable development. The findings provide some guidance to facilitate the achievement of SDGs especially among Muslim countries through their SCM practices. Studies which examined SCM practices for sustainable development from an Islamic perspective are limited. Therefore, the present study aims to provide additional insights on how SCM practices are used to promote sustainable development in line with Maqasid Al-Shariah principles. Some SCM practices are congruent with Maqasid al-Shariah particularly when the practices are examined through the Islamic lens that focuses the goal of creating value to mankind.

Keywords

Supply Chain Management, Maqasid Al-Shariah, Sustainable Development, Automotive Industry

Introduction

Extant literature suggests that positive impact of SCM on firm performance is attributed to the implementation of a specific set of SCM practices (Chow et al., 2008; Li, Zhou & Benton, 2007). SCM practices can be broadly defined as a set of activities undertaken by an organization as well as its trading partners (suppliers and customers) to promote effective supply chain management (Li et al., 2006; Spens & Wisner, 2009; Koh et al, 2007; Stock et al., 2010). Growing interest on SCM practices has led to various research investigating how various practices contribute towards performance, both at the firm (Truong et al., 2017) and supply chain level (Gawankar, Kamble & Raut, 2017). For example, past studies found that SCM practices positively influence firm performance through organizational culture (Kane-Urrabazo, 2006), customer relationship (Stock, Boyer & Harmon, 2010), information and communication technology (Li et al., 2006; Burgess, Singh & Koroglu, 2006), benchmarking and performance measurement (Saad & Patel, 2006), lean manufacturing, agile manufacturing, supplier relationship (Gorane & Kant, 2016) as well as supply chain integration (Sundram, Chandran & Bhatti, 2016). It is also suggested that these SCM practices create value to firms (Jääskeläinen & Heikkilä, 2019; Ketchen, Rebarick, Hult & Meyer, 2008), not only in the form of financial gains but also non-financial performance.

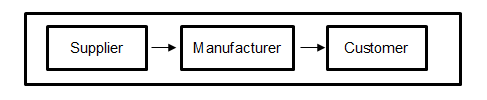

From the management perspective, SCM relates not only to the management of processes but also of relationships between main supply chain members. Basically, a supply chain is viewed as a chain of processes involved in ensuring that products reach the final customers through the cumulative effort of multiple supply chain business members linked together in the provision of those goods (Kasim, 2014). Hence, a basic SCM structure consists of three main members: (1) upstream suppliers of input such as providers of materials, (2) the manufacturer, as the focal firm, and (3) the downstream customer who receives the products manufactured (Figure 1).

Recent literature suggests that SCM practices can be employed to achieve sustainable development goals (Oelze et al., 2018; Ansari & Kant, 2017). Zimon, Tyan & Sroufe (2019) noted that the supply chain objectives in general include the aim to achieve economic, environmental, and social performance simultaneously. Common elements of sustainable SCM practices include sustainable supplier management, sustainable operations and risk management, and corporate social responsibility (Zimon et al., 2019). Similarly, Silva, et al., (2019) suggests that collaboration with stakeholders in a supply chain can be viewed as a driver of strategic change towards sustainability. However, there is still much to explore within the field of supply chain management and sustainability (Ansari & Kant, 2017; Dariah, Salleh & Shafiai, 2016), including in understanding how SCM practices play a role in promoting both sustainable development and Maqasid-Al-Shariah.

A possible starting point in examining how SCM practices are concurrent with the Islamic principles of Maqasid Al-Shariah. SCM practices follow Islamic principles that can be used in viewing supply chain systems. According to Holmberg (2000), the aim of monitoring the performance of a supply chain is to track not only the individual firm performance but also that of the other supply chain members. In this study, such a holistic approach of viewing a supply chain is deemed consistent with the concept of Maqasid Al-Shariah in Islam. This is because Maqasid Al-Shariah covers all aspects of life that are related to personal, social, economic, political and intellectual (Ullah & Kiani, 2017). As such, it encompasses broad-ranging principles that touch on all aspects of human life including not only at an individual level but also within a broader context such as in an organisation or even society as a whole. This is in line with the contemporary view of the application of Maqasid Al-Shariah which expanded to include a wider scope of people such as the community, a nation, or humanity, in general.

In line with this discussion, it is the contention in this study that SCM practices play a role in upholding Maqasid Al-Shariah. Moreover, our study argues that there is an expected congruence of sustainable SCM goals of promoting the wellbeing of organizations and ultimately society through improved firm performance, with the aims of Islamic Shariah in creating value to mankind. However, a review of the literature reveals very few studies could be found on the application or translation of Maqasid Al-Shariah into organisations, particularly in the field of supply chain management. In addition, studies which examine sustainable SCM practices from a Maqasid Al-Shariah perspective are almost unexplored. Given that the concept for Maqasid Al-Shariah is a reflective way of life which focuses on the importance of interest or human value, its implication in the context of organisational issues needs to be explored. This study focuses on the application of Maqasid Al-Shariah in sustainable supply chain management practices under three key principles. These principles are the protection of wealth, protection of mind and finally, protection of life. However, studies that examine the application of Maqasid Al-Shariah from the point of view of managing supply chains are still lacking. Hence, this study aims at addressing the question of: how is Maqasid Al-Shariah being applied in the context of SCM practices for sustainable development ?

Based on an extensive review of the literature, a conceptual model for the SCM application into Maqasid Al-Shariah is proposed. Using this model, a case study involving an automotive company operating in Malaysia is conducted to provide illustrations of the application of Maqasid principles in the SCM context. The selection of the automotive industry as the study context is based on the expected maturity of SCM implementation within the industry. As such, their SCM approaches in terms of management and processes provide a good illustration which offers valuable insights into the application of Maqasid Al-Shariah into SCM practices.

Literature Review

Supply Chain Management Practices for Sustainable Development

Min & Mentzer (2004) viewed Supply Chain Management (SCM) practices as consisting of not only supply chain-oriented activities inside the firm but also represent a set of collective managerial actions across the firms within the supply chain. Extant literature portrays SCM practices from a variety of different perspectives, but with a common goal of improving performance. Through SCM practices, organizations play a role in promoting sustainable development goals as stipulated by the United nations 17 SDGs (https://sdgs.un.org/goals).

Organizations strive for sustainability through the creation of economic wealth, apart from achieving social and environmental objectives. A common objective of the management of supply chains is to create value whereby when a business is successful in managing its SCM the resultant superior total performance of the supply chain delivers improved value to the customers. The value created will translate into economic wealth since value to firms is also perceived as the financial benefit in the form of higher profit margin (Ghosh & John, 1999). Ketchen, Rebarick, Hult & Meyer (2008) for instance, noted that when supply chains are able to deliver superior total value to the customer in terms of cost, quality, speed, and flexibility, overall supply chain performance will improve. Other studies discussed economic wealth in terms of value to the customer i.e., the benefits accruing to customers in terms of cost reduction or benefit enhancements (Ghosh & John, 1999). Several SCM practices have been identified in the literature as important vehicle for value creation within a supply chain environment including logistics (see Doran, 2004), information technology (see Wiengarten et al., 2011; Ryssel, Ritter & Gemunden, 2000), and supply chain integration (see Kim, 2009).

SCM practices are also found to support the achievement of SDG 8 relating to economic growth and decent work environment which promotes safe work environment (Gunaseelan & Gerald, 2017; Cantor, 2008). Organizations that place high emphasis on the importance of safety at the workplace is reflected by the common practice to set safety-related key performance indicators for SCM processes within the organization. He & Song (2011) noted that work safety is essential to maintain social stability and to develop a national economy in a healthy way. However, not all organizations are well-equipped with sufficient occupational safety measures in place. For instance, Abdul Zubar, et al., (2014) concluded that most of the manufacturing companies in Southern India are lacking in occupational health and safety management system. Similarly, Gunaseelan & Gerald (2017) suggested that while many manufacturing companies have the policy to reduce the accident rates, statistics still show a high rate of accidents and injuries happening in an organization.

Maqasid Al-Shariah (The Shariah’s Objectives)

Very few studies have explored the role of sustainable development goals from the Islamic point of view. Although Ahmed, et al., (2015) discussed the potential for Islamic finance to play a role in supporting the Sustainable Development Goals, they did not focus on sustainable SCM. One of the very important fundamental principles of Shariah is the objectives and goals of the Shariah itself i.e., the Maqasid Al-Shariah. Muslim scholars generally concur that Maqasid Al- Shariah refers to the purposes of law enforcement, as well as the secrets (hikmah) contained in law in order to safeguard human life in this world and in the hereafter. In other words, Maqasid Al-Shariah reflects the holistic view of Islam, which is a complete and integrated code of life encompassing all aspects of life, be they individual or social (Dusuki & Abdullah, 2007). This is consistent with the overall aim of Islamic law (Shariah) which is to promote welfare or benefit (MaÎlaÍah) of mankind and prevent harm (Mafsadah) (Ahmed, 2012).

According to Imam Al-Ghazali, Maqasid Al-Shariah serves as the interest to human being and to save from harm. An understanding of the maqasid is thus important for gaining an insight into the rest of the syariah. According to Kamali (2000), syariah is often described as ‘diversity within unity’ which implies diversity in interpretations but unity in the goals and objectives. The objectives of the syariah are described in the Quran in several verses when it speaks:

“O mankind, a direction has come to you from your Lord; it is a healing for the spiritual ailments in your heart and it is guidance and mercy for the believers” (Quran, Surah Yunus: 57). The message here exceeds all barriers that divide humanity, and commands that mercy and beneficence intended by Allah for all mankind must be preserved. This is further supported by another verse of the Quran in which it describes the purpose of the Prophet’s mission to be mercy not only to humans but to all Allah’s creatures. In another verse, the Quran speaks:

“Allah commands justice, the doing of good, and liberality to kith and kin, and He forbids all shameful deeds, and injustice and rebellion: He instructs you, that you may receive admonition” (Quran, Surah an-Nahl: 90).

According to Imam Al Ghazali, Maqasid Al-Shariah revolves around five principles or objectives, namely, protection of faith (al-din), protection of life (al-‘nafs), protection of intellect (al-‘aql), protection of lineage (an-nasl) and protection of property (al-mal/wealth). In recent years, the application of Maqasid Al- Shariah in various disciplines including social and economics has been gaining eminence (Ullah & Kiani, 2017; Shinkafi & Ali, 2017). Similarly, Mohd Yusob, et al., (2015) suggest that many Islamic scholars today attempt to accommodate the application of Maqasid Al-Shariah in a plethora of complex and complicated issues.

In principle, the main aim of the implementation of the Shariah and Islamic teaching is to preserve the welfare of human life and avoid any disadvantages (Al- Ghazali, 1937). It is an extension and expansion oriented concept that focuses on the importance of interest in human improvement. A distinct element of Maqasid Al-Shariah is that it provides clear guidance and framework in solving the issues conforming to the human interest not only for Muslims but also mankind as a whole to suit the modernization of human needs (Alam, Hassan & Said, 2015). The knowledge of Maqasid Al-Shariah is crucial in order to understand or interpret the texts of Shariah, as well as to derive solutions to contemporary problems faced by mankind including organizational issues. Thus, an understanding of the Maqasid Al-Shariah is important for gaining an insight into the Shariah as it relates to modern management tools such as Supply Chain Management (SCM) practices.

Conceptual Model of the Application of Maqasid Al-Shariah into SCM for Sustainable Development

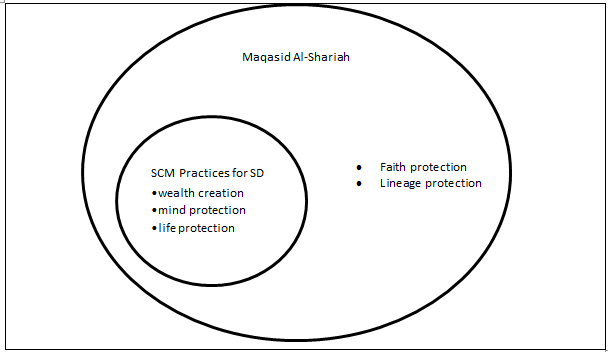

Drawing from the current literature, a conceptual model (Figure 2) is advanced in this study to discuss the research questions identified in the previous section. As presented in Figure 2, the proposed model puts forward three key components of Maqasid Al-Shariah as applied in SCM practices for sustainable development consisting of protection of wealth, protection of mind and protection of life. Each of these components is explained in the following sections.

Figure 2: A Conceptual Model of Application of Maqasid Al-Shariah Into Scm for Sustainable Development

Protection of Wealth (Al Mal)

Realizing Maqasid Al-Shariah hereafter, and its scope covers all activities of ‘ibadah (religious rituals) and mu’amalah (economic transaction), this principle is, therefore, a crucial factor to be considered in developing and structuring Shariah compliant automotive. This would require structuring the industry and services in accordance with Islamic principles. Adhering to the elements and features of right values would also mean protecting and safeguarding maslahah (benefits) and preventing or repelling the mafsadah (harms) in all dimensions of human life by upholding to the principles of Maqasid Al-Shariah (Daud, 2019). The automotive industry particularly should make an effort to ensure that the Maqasid element is strictly taken into account in setting their objectives and policies. The present study proposes that the idea of value creation is synonymous to the notion of wealth generation under Maqasid Al-Shariah.

From the SCM perspective, several notions of value creation have been suggested in the literature. Cox (1999) for instance, noted that value is created when a business is successful in managing its SCM such that the resultant superior total performance of the supply chain delivers improved value to the customers. Although not many studies have defined value creation as it applies to SCM, value to the customer generally refers to the benefits accruing to them in terms of cost reduction or benefit enhancements (Ghosh & John, 1999).

Several SCM practices have been identified in the literature as the important vehicle for value creation within a supply chain environment. These include relationship management (see Hovarth, 2001; Ha et al., 2011), logistics (see Doran, 2004), information technology (see Wiengarten et al., 2011; Ryssel, Ritter & Gemunden, 2000), and supply chain integration (see Kim, 2009). Supply chain relationship management mainly relates to cooperation and collaboration among the supply chain members. Hovarth (2001) noted that the collaboration among supply chain members, when applied together with advanced SCM practices will enable businesses to reduce costs, create more value for customers and detect critical demand changes quickly enough to design and execute optimal responses. In contrast, according to Ha, et al., (2011), collaboration significantly creates value to the firm in terms of logistics efficiency but on the condition that there must be some amount of trust that could significantly influence such collaboration.

Protection of Mind (Al- ‘Aql)

In the Quran, the word management is mentioned to mean regulate, govern, rule and ponder (Surah al-Sajdah, 5; Surah al-Ra’d, 11). Through adopting the right values, an individual in an organization will possess dynamic attitudes which include optimism, confidence and willingness to seek for excellence in whatever he is doing. Thus, Islam plays a very contributive and determining successful factor whereby the Islamic values system which is based on truth, justice and brotherhood provides the emphasis on the notion of value creation to all mankind (Daud et al., 2019). Maqasid Al-Shariah emphasizes the importance to ensure justice and maslahah (welfare) to the members in an organization such as the management team and the general workers in the company. These protections by way of Maqasid Al-Shariah seek to make the life every individual and community to be more secure, knowledgeable, skillful and peaceful. From the organization’s perspective, companies are expected to produce quality, useful and safe products and services to their consumers.

Thus, companies pursuing SCM need first re-organise their human resources and transform their company culture and then think about the technical aspects of the implementation process. Commitment to teamwork, advanced communication skills, internal developers’ training, transformational leadership and organisational “openness” reflected in the willingness for information sharing represents among the key factors for successful implementation under SCM strategies. This requires a corporate culture that emphasizes the value of sharing common goals over individual pursuits and the value of trust between partners, employees, managers and corporations. Having trained employees in SCM’s philosophy across the organisation is also a must for any successful Maqasid Al-Shariah implementation. Of course, many organisational implementation issues have yet to be resolved. Future research should focus on how firms pursuing Maqasid Al-Shariah should change personnel’s attitudes and behaviour and manage the organisational change required for successful SCM implementation.

Protection of Life (An-Nafs)

In Islam, quality, safe and hygienic production process, fair prices and dealings, halal and haram are considered as objectives of the Shari‘ah (Haniffa & Malik, 2002; Dusuki, 2008). Maqasid Al-Shariah includes in term of the workplace like providing adequate training, maintaining equipment in good working condition, maintaining a safe working environment. This includes protecting health and safety, treating employees fairly in terms of wages, working hours, investing in education and training. According to Sahih Muslim Vol.3, Hadith No.4093, Allah has placed those (employees) under you. They are your brothers. So anyone of you has someone under him, he should feed him out of what he himself eats, clothes him like he himself puts on. You should not overburden him with what he cannot bear, and if you do so, help him in his job. The Prophet said in a Hadith Qudsi, “God said, “I will oppose three types of people on the Day of Resurrection’ and among these He mentioned ‘one who employs a laborer, has the whole job completed by him, but does not pay him for his labor” “I have made oppression unlawful for Me and for you, so do not commit oppression against one another” (Sahih Muslim, Vol. 3 Hadith No.6254).

Methodology

This study used the qualitative method for research enquiry using a single case study approach in order to illustrate the observed patterns of attributes found in the case company. The fundamental goal of a case study research is to conduct an in-depth analysis of an issue, within its context with a view to understand the issue from the perspective of participants (Merriam, 2009; Yin, 2014). Due to the limited studies on supply chain management in the Maqasid Al- Shariah context, this study is viewed as likely to contribute as a revelatory opportunity to study such a phenomenon in depth (Yin, 2003).

This study collected data from major automobile companies operating in Malaysia. The research process consists of four main stages:

Stage 1: Literature review, identification of research variables and preparation of interview protocol

Stage 2: Pilot interviews followed by review and revision of interview protocol

Stage 3: Main study

Stage 4: Data analysis and report writing

Stage 1 of the research process began with an extensive review of the literature to identify the current state of knowledge in the field, relevant frameworks and factors to be considered in the current study. This was followed by the identification of research variables as well as the appropriate research methodology and procedures. Consequently, an interview protocol was prepared as a guide for semi-structured interviews to be conducted in this study.

Stage 2 involved conducting pilot interviews with several experts in the automotive industry. This was done in order to obtain a better understanding of SCM processes and the link with Maqasid Al-Shariah. These practitioners consisted of senior managers at an automobile company. In this stage, consistent with Yin (2014), the pilot study aimed to test the applicability of factors identified in stage 1. Hence, the pilot interview served as a means of revising the interview protocol and to achieve external validity of the research constructs.

Stage 3 was the main study whereby during this stage, semi-structured interviews, observation and document reviews were conducted. The objective of the interviews and focus group discussions is to address the following main research issues: How is Maqasid Al-Shariah being applied in the context of supply chain management practices? Specifically, this is subdivided into the following questions:

1. What role do the SCM practices play in promotion of Maqasid Al-Shariah for the protection of wealth?

2. What role do the SCM practices play in promotion of Maqasid Al-Shariah for the protection of mind?

3. What role do the SCM practices play in promotion of Maqasid Al-Shariah for the protection of life?

Stage 4 finally involved transcribing and coding of the data. Data was analysed by applying Yin’s (2009) pattern matching logic together with more specific analysis as suggested by Bloomberg & Volpe (2008); Miles & Huberman (1994).

Data Collection

The primary data was gathered mainly through semi-structured interviews which were conducted using open-ended interview questions. The interviews served as a means to elicit in-depth information on SCM practices based on the informants’ views, beliefs and actions at their disposal about the practices implemented by the company. The interviews lasted on average one hour per session. The data was recorded, and the process was facilitated by interview protocols.

The participants include key personnel who were expected to be familiar with SCM such as the production executives, procurement personnel as well as the logistics personnel. All data were tape-recorded supplemented by field notes. The data were then transcribed and coded by linking the data to the propositions using a “pattern-matching” approach (Yin, 2003). Due to the need to maintain confidentiality about the company, this study provides the name of the case company as Putra. Additionally, a review of documentation such as websites, newspaper clippings, and archival records was also conducted.

Findings

Case Illustration

Case Background

Putra is a manufacturing subsidiary of a holding company. This company was set up with a mission to produce compact and more affordable vehicles for the Malaysian market. It was incorporated as a joint venture involving several local companies with three Japanese companies and this remains until today. The manufacturing plant covers an area of 64,000 square meters and has the capacity to produce 350,000 units per annum. It is equipped with manufacturing facilities which consist of the press shop, body shop, paint shop, and assembly shop. Other facilities include a logistic, training centre, quality audit, pre-delivery inspection (PDI), stockyard and parts warehousing. Due to the effective majority control by the Japanese firms over the manufacturing plant, Putra takes instruction and reports regularly to the Japanese parent companies.

SCM and Protection of Wealth

It has been recognized that SCM practices have been implemented for the creation of value. This is in line with the concept of wealth generation and protection within the purview of Maqasid Al-Shariah as proposed in the conceptual model discussed earlier (Figure 2). Findings from Putra illustrates three key SCM practices that generate and protects wealth within the organization. As the aim of this study is to highlight and illustrate how SCM practices are implemented in line with Maqasid Al-Shariah, only selected practices are included within the scope of this study. The selection is based on the significance and relevance of these practices to the Maqasid Al-Shariah itself. These practices consist of logistics, integration and relationship management practices (Table 1).

| Table 1 Wealth- Protecting Scm Practices In Putra |

|

|---|---|

| Key SCM Practices | Dimensions of SCM practices wealth generation |

| Logistics | · Supplier selection · Supplier control |

| Integration | · Cross-functional teamwork in SCM decisions · Supplier involvement in process improvements |

| Relationship | · Trust-based relationship · Supplier rating, incentives and rewards |

Under the logistics practices, Putra implemented various logistics practices in dealing with safeguarding resources and property, which is one of the principles in Maqasid Al-Shariah. Preserving property means protecting the wealth of the company from destruction and from transferring property into the hands of others in an unlawful way including injustice, denying rights and so on. In particular, protection of wealth is noted in the planning and control of purchasing decisions. For instance, a careful selection of suppliers by Putra ensures that supplies of materials will be delivered on time and in the right quantity needed for production. Emphasis was placed on implementing supplier selection and control practices that would lead to wealth generation in the form of cost savings, higher quality, faster speed and higher flexibility. Putra conducts careful considerations together with the imposition of stringent criteria for selecting suppliers to ensure that only credible suppliers who are able to deliver the materials at the right price, the right quantity, the right location and at the right time. Such practice is important particularly in ensuring conformance to specifications and meeting delivery deadlines.

The findings further illustrate how Putra implemented integration practices in their pursuit of wealth generation through cost savings, higher profit margin, faster delivery and higher flexibility. Supply chain integration practices within Putra consists of cross-functional teamwork and supplier involvement practices. Findings suggest that integration by way of close cooperation and constant coordination among internal departments in Putra help prevent inter-departmental conflicts, hence avoiding unnecessary costs of production delays. Furthermore, the participation of suppliers in cost reductions activities helps Putra to achieve its own target of cost reduction. Suppliers would also benefit from this activity as their achievement of cost reductions increases the likelihood of being awarded future contracts with Putra. Hence, it leads to a win-win situation for both Putra and its suppliers which in turn results in significant cost savings from such supplier involvement.

Besides that, relationship management practices in Putra contribute towards wealth generation and protection in line with Maqasid Al-Shariah. For instance, a long term partnership established with the selected suppliers fosters a good working relationship that helps prevent injustice and oppression. The Holy Quran has pronounced all mankind as one compared it to a single entity in which the individual cannot do without the others and vice versa. The unitary view provides a dynamic direction for good teamwork in an organization. In line with the spirit of instilling interpersonal and strong teamwork in an organization, Islam gives a clear and definitive explanation about man. It regards man as the best of all creations. Allah swt says to the effect that: “We have indeed created man in the best of moulds. Then do We abase him (to be) the lowest of the low, except such as believe and do righteous deeds: for they shall have a reward unfailing”, (Surah al-Tin, Verses 4-6). Resolving the tug of war between personal and organizational interests in favour of the organization is one of management’s greatest difficulty. The Quran puts forward a reminder on this matter: “But the transgressors among them changed the word from that which had been given them so We sent on them a plague from heaven for what they repeatedly transgressed”, Surah al-A’raf, 162). Hence, by having supply chain integration practices, more harmony is achieved within the organisation. In particular, the integration practices by both companies are regarded as good practice since it will make business dealings and transactions easier, which will lead to higher productivity. This further fulfils the Maqasid Al-Shariah by achieving the purpose of safeguarding and protecting business properties in the form of cost savings.

SCM and Protection of Mind

As shown in Figure 1, the second application of Maqasid Al-Shariah into SCM practices relates to the protection of the mind (Al-‘Aql). The preservation of the intellect or the mind refers to the means to protect the human mind from anything that is harmful not only to an individual but also to members of the organization as a whole. Within SCM perspective, the safeguarding of the mind is achieved through training and education of employees as well as other stakeholders such as their suppliers. The mastery of knowledge in SCM is fundamental to the progress and development of the workers (maintenance of mind) in implementing their respective jobs. In the face of globalization challenges, education programs, trainings and knowledge should be the focus of producing human resources that not only have knowledge and skills but also have values that contribute to the development of the company and humanity.

Employee morale is viewed as an important aspect within Putra in their effort to safeguard the mind of its workers. Having a highly motivated workforce with the appropriate attitude help ensures the overall success of the firm. The employees of all levels including the operational employees are required to undergo certain training and development activities in order to acquaint themselves with acceptable work ethics and standards. These trainings support the acquisition of skills of the workers, after which they will be evaluated based on several competent levels, ranging from basic competence up to very competent level. Apart from that, the trainings on work-related competencies, several human development activities are also conducted as a means to instil the right attitude among workers. For instance, a program called Kursus Dinamik Kumpulan is organized for the non-executive employees specifically to build the best personal qualities. It normally involves external consultants who conduct the program for a small group of around twenty individuals. During these programs, the employees will attend motivational talks and various other activities that help with upgrading their life skills.

In recognition of the importance of appreciating their workforce, Putra also organizes activities to boost morale such as giving simpler rewards for continuous improvement initiatives. An example is the ongoing kaizen scheme organized at the operational level. An interviewee noted:

We organize an annual kaizen scheme whereby people at the shop-floor level may come up with an idea to improve their work. They just need to put it on a piece of paper and we reward them with one ringgit for each kaizen idea submission. Then, if their idea is chosen to the next level, they will prepare a concept paper and make some presentation. If the idea is interesting enough they will go to the final round and the winner will be rewarded financially.

Therefore, findings from Putra suggest that such training and education practices were found to be an essential platform for the company to nurture noble values and beneficial knowledge. Elements that lead to loss and damage to the mind and thoughts such as selfishness, fraud, bribery and other negative thoughts that could harm the company’s reputation could be prevented. As a result, these practices promote trusts among employees and also between the companies and their suppliers. Such a trust-based relationship is found to deepen cooperation and leads to greater performance benefits for the firm and its supply chain partners.

SCM and Protection of Life

As shown in Figure 2, SCM practices for the protection of life has been identified as the third element in the conceptual model in applying Maqasid Al-Shariah into SCM. Case findings suggest that Putra place high importance in safeguarding the life of its workers. By putting in place strict rules and regulations for them to follow. This is complemented by the serious effort of setting key safety measures within Putra which is to have zero industrial accidents within the plant. Apart from adopting internal rules and machine safety standards, various complementary action plans are identified and documented within the company as additional precautionary measures to avoid the accidents. For example, critical departments that are likely to face greater accident risks are required to identify accident-prone areas and take preventive measures accordingly. Within the logistics department, the indoor area where forklifts are used in handling materials has been identified as a potentially hazardous zone. In response to this risk, the firm has initiated plans to limit the use of forklifts to the outdoor area where accidents may be prevented. Similarly, in the past, materials received from suppliers were stored using ‘high racks’ which necessitated the use of certain material handling equipment that could seriously cause injuries to the employees. In consideration of the potential hazards that these high racks could create, the case firm then decided to replace them with safer alternatives.

Another example where accident risks are reduced in Putra is by preventing an overflow in the materials storage area. Such overflow of materials may occur when the storage racks are filled up to the maximum. Materials which are received using the conventional Kanban method are still required to be stored temporarily at the Production Control (PC) racks. The use of the PC racks are intended to control the volume of materials received by maintaining the storage volume within the minimum-maximum level set for each rack. The racks must be sufficiently filled above the minimum level so as to prevent inventory stock-outs. At the same time, the volume of storage has been monitored so that it must not exceed the maximum level. Putra takes the necessary precaution to avoid overflow of material, particularly when there is an incident of downtime. Downtime in the factory would usually cause congestion to the work area and may lead to accidents. Hence, by closely monitoring the material level and implementing stricter material control system, accidents that endanger the life of workers could be prevented. The findings demonstrated that as an automotive manufacturer, safety concerns are of utmost importance to the firm. This is in line with the protection of life principle of Maqasid Al-Shariah.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Given the lack of extant research that addresses the SCM practices from the Islamic viewpoint, the current study commenced by examining several distinct SCM practices with objectives that are aligned with key principles of Maqasid Al-Shariah. The main findings were that the success of these practices in generating and protecting wealth within the automotive industry is broadly attributable to an effective integration of three key SCM practices as identified in the study. When these practices namely logistics, integration and relationship-based practices are integrated, the case firm experienced higher supply chain performance. The findings also demonstrated that wealth generation resulting from these integrated SCM practices implies overall value enhancement for firms in both financial and non-financial terms.

Drawing on the Quran and Sunnah, several implications for wealth generation are noted. Firstly, the divine guidelines as postulated by the various Islamic principles, rulings and legislation all aim for the betterment of an individual and ultimately the society and mankind as a whole. This argument leads to the notion that whatever good is being done as an individual will be then translated as improvement effort that creates values. From an organisational context, similar argument prevails since an organisation is an entity comprising multiple individuals that has a particular purpose. Secondly, the value being created for an individual according to Maqasid Al-Shariah will differ from values created within organisations. While benefits to individuals are manifested in terms of spiritual healing and divine guidance, advantages to organisations are relatively more universal such as higher profitability, financial stability and prosperity. Thus, these findings support our contention that SCM practices are in line with the wealth protection principle of Maqasid Al-Shariah.

In addition, the findings also highlighted the Islamic values as being universal in nature, inherently providing guidelines for organisations to support the objective of protecting human mind and life. These values are manifested in the findings from Putra. Using various training and education on SCM, the workers are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills for them to implement their respective tasks. However, a key difference between Islamic approaches and the influence of Japanese SCM as practised in Putra highlights that the Japanese put tremendous emphasis on the individual worker, his attitude, his loyalty, his passion and above all his service to the customer, both in terms of product quality as well as after-sales service. In contrast, the Maqasid Al-Shariah views these practices more holistically in accordance with three levels of priority, i.e., daruriyyat (basic obligation), hajiyyat (necessity) and tahsiniyyat (perfection). From an organisation perspective, this implies that business affairs also need to focus on virtuous intentions particularly to safeguard properties and mind.

Overall, these findings contribute to the body of knowledge and practitioners in both the SCM field and Islamic principles. This contribution is important because it supports and extends previous research on SCM practices within the Malaysian automotive context. However, more importantly, the study provides an added insight into SCM practices that promote Maqasid Al-Shariah. In the present era, to be competitive an organization has to involve its workers seriously in the process of continuous learning. Organization that has the knowledgeable working force implies the ability of the workers to perform functions in the most effective, productive and cohesive manner. Allah SWT says in the Quran to the effect that “That was a people that hath passed away. They shall reap the fruit of what they did, and ye what ye do! Of their merits there is no question in your case.” (Surah al-Baqarah, 141).

Although the use of case studies method in this research highlighted the gap of Maqasid Al-Shariah in SCM, the study inevitably suffers from the limitations inherent in case study research. As with other case studies, the use of a single case company limits the capacity to generalise the findings to a larger population of manufacturing companies. Therefore, these findings should be treated with caution, and more robust empirical means than those employed here are still needed to provide further empirical evidence in generalising these findings in a population. In particular future research could focus on using quantitative line of enquiry. Furthermore, the present study covers only three elements in Maqasid Al-Shariah i.e., the safeguard of wealth, properties and mind. It is recommended that future research examine other elements of Maqasid Al-Shariah. Therefore, this study will serve as a base forfuture SCM studiesin Islamic jurisprudence.

References

- Abdul Zubar, H., Visagavel, K., Deepak Raja, V., & Mohan, A. (2014), “Occupational health and safety management in manufacturing industries”. Journal of Scientific & Industrial Research, 73, 381-386.

- Ahmed, H., Mohieldin, M., Verbeek, J., & Aboulmagd, F. (2015).On the sustainable development goals and the role of islamic finance.Policy Research Working Paper; No. 7266.World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Ahmed, H. (2012). “Maqasid Al-Shariah and Islamic financial products: A framework for assessment”. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, 3(1), 149-160.

- Ansari, Z., & Kant, R. (2017). “Exploring the framework development status for sustainability in supply chain management: A systematic literature synthesis and future research directions: Sustainable supply chain management frameworks”. Business Strategy and the Environment,26(7).

- Bloomberg, L.D., & Volpe, M.F. (2008). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A Roadmap from Beginning to End. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Burgess, K., Singh, P.J., & Koroglu, R. (2006). “Supply chain management: a structured literature review and implications for future research”. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(7), 703-729.

- Cantor, D. (2008). “Workplace safety in the supply chain: A review of the literature and call for research”. International Journal of Logistics Management, 19(1),65-83.

- Chow, W.S., Madu, C.N., Kuei, C.H., Lu, M.H., Lin, C., & Tseng, H. (2008). “Supply chain management in the US and Taiwan: An empirical study”. Omega, 36(5), 665–679.

- Daud, D. (2019). “The role of Islamic governance in the reinforcement waqf reporting: SIRC Malaysia case”. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 10(3), 392-406.

- Daud, D., Ismail, A.M., Rahman, R.A., Sadique, R.B.M., & Zakaria, N.B. (2019). “Perceptions of Waqf reporting practices by state religious islamic councils”. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE), 8(4), 1092-11098.

- Dariah, A.R., Salleh, M.S., & Shafiai, H.M. (2016). “A new approach for sustainable development goals in Islamic perspective.Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,l.21(9), 159-166.

- Doran, D. (2004), “Rethinking the supply chain: An automotive perspective”. Supply chain management: An International Journal, 9(1), 102-109.

- Drucker, P. (1995). “The information executives truly need”. Harvard Business Review, 54-62

- Dusuki, A.W., & Abdullah, N.I. (2007). “Maqasid alShari`ah, Maslahah and Corporate Social Responsibility”. The American Journal of Islamic Social Science, 24(1), 25-45.

- Gawankar, S.A., Kamble, S., & Raut, R. (2017). “An investigation of the relationship between Supply Chain Management Practices (SCMP) on Supply Chain Performance Measurement (SCPM) of Indian retail chain using SEM”. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 24(1), 257-295.

- Ghosh, M., & John, G. (1999). “Governance value analysis and marketing strategy”. Journal of Marketing, 63, 131-145.

- Gorane, S., & Kant, R. (2016). “A case study for predicting the success possibility of supply chain practices implementation using AHP approach”. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 31(2), 137-151.

- Gunaseelan, V., & Gerald, L.A. (2017), “Study on safety management system of manufacturing industry”. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 4(12), 788-790.

- Ha, B.C., Park, Y.K., & Cho, S. (2011). “Suppliers’ affective trust and trust in competency in buyers: Its effect on collaboration and logistics efficiency”. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 31(1), 56-77.

- Haniffa, R., Hudaib, M.A., & Malik, A.M. (2002). Accounting Policy Choice within the Shari’ah Islami’iah Framework. www.ex.ac.uk/sobe/research/discussionpaper, 25.

- He, X., & Song, L. (2011), “Basic characteristics of work safety in China”. Procedia Engineering, 26, 1-9.

- Holmberg, S. (2000). “A systems perspective on supply chain measurements”. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 30(10), 847-868.

- Holy Qur’an. (2000). Original Arabic text with english translation & selected commentaries. (Yusuf Ali A. Trans.). Kuala Lumpur: Saba Islamic Media.

- Jääskeläinen, A., & Heikkilä, J. (2019), “Purchasing and supply management practices in customer value creation”. Supply Chain Management, 24(3), 317-333.

- Kamali, M.H. (2000). Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence. Kuala Lumpur: Ilmiah Publishers.

- Kane-Urrabazo, C. (2006). “Management's role in shaping organizational culture”. Journal of Nursing Management, 14(3), 188-194.

- Kasim, E.S. (2014). Supply chain management practices and performance measures: Case evidence from Malaysian automotive manufacturers (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam.

- Ketchen, D.J., Rebarick, W., Hult, G.T.M., & Meyer, D. (2008). “Best value supply chains: A key competitive weapon for the 21st century”, Business Horizons, 51(3), 235-243.

- Kim, S.W. (2009). “An investigation on the direct and indirect effect of supply chain integration on firm performance”. International Journal of Production Economics, 119(2), 328–346.

- Koh, S.C.L., Demirbag, M., Bayraktar, E., Tatoglu, E., & Zaim, S. (2007). “The impact of supply chain management practices on performance of SMEs”. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 107(21), 103-124.

- Li, S., Ragu-Nathan, B., Ragu-Nathan, T.S., & Rao, S.S. (2006). “The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance”. Omega, 34(2), 107-124.

- Mohd Yusob, M., Salleh, M., Haron, A., Makhtar, M., Asari, K., & Jamil, L. (2015). “Maqasid al-Shariah as a parameter for Islamic countries in screening international treaties before ratification: An analysis”. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 23.

- Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M.B., & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Min, S., & Mentzer, J.T. (2004). “Developing and measuring supply chain management concepts”. Journal of Business Logistics, 25(1), 63-99.

- Oelze, N., Brandenburg, M., Jansen, C., & Warasthe, R. (2018). “Applying sustainable supply chain management frameworks to two German case studies”. IFAC PapersOnLine, l.51(30), 293-296.

- Ryssel, R., Ritter, T., & Gemunden, H.G. (2000). Trust, commitment and value-creation in inter-organizational customer-supplier relationships. Paper presented at the 16th IMP Conference, Bath.

- Saad, M., & Patel, B. (2006). “An investigation of supply chain performance measurement in the Indian automotive sector”. Benchmarking: An International Journal of Accountancy, 13(1/2), 36-53.

- Shinkafi, A.A. & Ali, N.A. (2017). “Contemporary Islamic economic studies on Maqasid Shari’ah: A systematic literature review”. Humanomics, 33(3), 315-334.

- Spens, K., & Wisner, J. (2009). “A study of supply chain management practices in Finland and the United States”. Operations and Supply Chain Management, 2(2), 79-92.

- Stock, J.R., Boyer, S.L., & Harmon, T. (2010). “Research opportunities in supply chain management”. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(1), 32–41.

- Sundram, V.P.K., Chandran, V.G.R., & Bhatti, M.A. (2016). “Supply chain practices and performance: The indirect effects of supply chain integration”. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 23(6), 1445-1471.

- Truong, H.Q., Sameiro, M., Fernandes, A.C., Sampaio, P., Duong, B.A.T., Duong, H.H., & Vilhenac, E. (2017). "Supply chain management practices and firms’ operational performance. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 34(2), 176-193.

- Ullah, S., & Kiani, A.K. (2017). “Maqasid-al-Shariah-based socio-economic development index (SCECDI): The case of some selected Islamic economies”. Journal of Emerging Economies & Islamic Research, 5(3), 32 – 44.

- Wiengarten, F., Fynes, B., Humphreys, P., Chavez, R.C., & McKittrick, A. (2011). “Assessing the value creation process of e-business along the supply chain”. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 16(4), 207–219.

- Yin, R.K. (2014). Case study research design and methods, (5th edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research, (3rd edition). London, England: Sage Publications.

- Zhou, H., & Benton Jr., W.C. (2007). “Supply chain practice and information sharing”. Journal of Operations Management, 25(6), 1348–1365.