Research Article: 2023 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

Association of Political Connections and Executive Compensation with Tax Aggressiveness

Alicia Karina Limawal, Universitas Ciputra

Eko Budi Santoso, Universitas Ciputra

Stanilaus Adnanto Mastan, Universitas Ciputra

Citation Information: Limawal, A.K., Santoso, E.B., & Mastan, S.A. (2023). Association of political connections and executive compensation with tax aggressiveness. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 22(S3), 1-11

Abstract

Tax Aggressiveness is one of the important determinants of low tax ratio in Indonesia. The large number of taxpayers participating in the tax amnesty program indicates the high practice of tax aggressiveness that has occurred. This study aims to examine political connection associations and executive compensation for company tax aggressiveness. Political connections are measured using dummy variables, executive compensation is measured using natural logarithms of total compensation received for a year, and tax aggressiveness is measured using the GAAP ETR proxy, ETR Cash, and Current ETR. The research data was taken from the annual reports of companies in the manufacturing sector for the period of 2015-2017 and produced 315 observations. The analysis in this study uses multiple regression and gives results that there is a positive association between political connections and executive compensation with the company's Effective Tax Rate. This indicates that companies with political connections and high executive compensation tend to be more compliant or avoid tax aggressiveness.

Keywords

Political Connection, Executive Compensation, Tax Aggressiveness, Tax Compliance.

Introduction

Indonesia is one of the developing countries whose biggest main source of income comes from tax revenues. Table 1 shows that more than 80% of state revenues are contributions from tax revenues.

| Table 1 Realization Of State Tax Revenues (In Billion Rupiah) In 2015-2017 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source Penerimaan | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| I | Revenue | 1,496,047 | 1,546,947 | 1,732,952 |

| Tax Revenue | 1,240,419 | 1,284,970 | 1,472,710 | |

| Non-Tax Revenue | 255,628 | 261,976 | 260,242 | |

| II | Grants | 11,973 | 8,988 | 3,108 |

| Amount | 1,508,020 | 1,555,934 | 1,736,060 | |

| Percentage of tax revenue to total state revenues | 82.25% | 80.27% | 84.83% | |

However, Indonesia's tax ratio is still low. The tax ratio shows the low tax revenue compared to gross domestic product. Data from the Ministry of Finance (2018) regarding the 2018 State Budget shows that Indonesia's tax ratio in 2017 is at 10.7% and rises to 11.6% in 2018. However, this value is still low compared to the ideal tax ratio of 15-16%. In addition, this value is still lower compared to other ASEAN countries. OECD data (2017) shows several ASEAN countries that have similar economic sizes in Indonesia have higher tax ratio values, namely Thailand (18.1%), Malaysia (14.3%), Philippines (17%) and Singapore (13, 5%).

The low value of the tax ratio is caused by several things, one of which is aggressive tax avoidance measures carried out by taxpayers (tax aggressiveness). Tax aggressiveness is part of tax planning but is done with the aim of maximizing the company's profits by taking the risk to remain undetected by the tax authority, so the company is more aggressive in carrying out its tax reduction strategy (Martinez, 2017). The existence of tax aggressiveness can potentially reduce state revenues from the tax sector. The research results of Cobham & Jansky (2017) using data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that Indonesia was ranked highest among ASEAN countries and ranked 12th out of 145 countries with the biggest loss from tax avoidance measures, totaling at 7.48 billion dollars or equivalent to 104.72 trillion rupiahs, which could potentially increase the tax ratio to close to 1%. In addition, the large numbers of taxpayers who utilize the tax amnesty program are indicative of the pre-existing common phenomenon of tax evasion in Indonesia.

The actions of corporate tax aggressiveness can be influenced by several things. This study aims to look at the association of political connections and executive compensation for the company's tax aggressiveness. Political connections are chosen because many companies in Indonesia have political connections and use them for the benefit of the company (Fisman, 2001; Harymawan, 2018, Wicaksono, 2017). In Indonesia, many public officials have held important positions in the company during or after their service as public officials. Owned political connections are often used by companies to carry out tax aggressiveness because with this political connection, companies will face low pressure on transparency and law enforcement due to company actions (Kim & Zhang, 2016).

Another factor that can be associated with the company's tax aggressiveness is executive compensation. The executive as the party appointed to manage the company has a mandate to improve the welfare of shareholders. The compensation given for the mandate is followed by demands those executives are able to meet shareholders' expectations, one of which is to minimize the tax burden (Mayangsari et al., 2015). The greater the compensation given to executives, the greater the level of tax aggressiveness that will be done by the company (Amri, 2017).

This research was conducted on companies engaged in the manufacturing sector because because the number of companies in this sector constituted 20% of all companies listed on the Stock Exchange, which was the largest contributor of state revenues from the tax sector. Table 2 shows the contribution of the manufacturing sector to state revenues from corporate taxpayer income tax.

| Table 2 The Percentage Of 2017 Tax Revenue Contribution Based On Business Classification |

||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Sector | Percentage |

| 1 | Manufacture | 31.80% |

| 2 | Finance | 19.30% |

| 3 | Trading | 14% |

| 4 | Agriculture | 1.70% |

Source: Ministry of Industry, 2018.

However, the large contribution does not necessarily reflect the level of tax compliance. In the case of corporate tax avoidance of PT. Toyota Motor Manufacturing Indonesia and PT. Asia Pulp & Paper are examples that tax avoidance activities also occur in the manufacturing sector.

In addition, studies on political connections, executive compensation, and tax aggressiveness provide inconclusive results (Tehupuring & Rossa, 2016; Pranoto & Widagdo, 2016; Ayu, 2017; Armstrong et al., 2015; Mayangsari et al., 2015; Ying et al., 2017; Abdul-Wahab et al., 2017; Wicaksono, 2017). So, in this study three proxies of tax aggressiveness were used, namely GAAP Effective Tax Ratio (ETR), Cash ETR, and Current ETR.

Conceptual Framework and Development of Hypotheses

Tax planning

Tax planning is a tax reduction strategy that can be done legally or illegally (Martinez, 2017). Tax planning is said to be legal if it is done by exploiting weaknesses in tax regulations that facilitates the reduction of taxes. Tax planning is said to be illegal if done in ways that violate tax regulations.

Figure 1 illustrates tax planning as a tax reduction strategy that covers all activities, including both implicit and explicit tax types. The tax planning action is categorized as tax avoidance if it is done with the aim of maximizing profit after tax and as tax aggressiveness if it is done by considering the possibility of the company not being examined by the tax authority. The company is categorized as conducting tax evasion if the tax reduction strategy is carried out illegally and has violated applicable tax regulations.

Tax Aggressiveness

According to Martinez (2017), tax aggressiveness is a more aggressive form of tax avoidance. The weaker the existing tax regulations are, the more the company will be more aggressive in minimizing the tax burden that must be paid. The size of the possibility of the company not being examined by the tax authority (> 50%) is also one of the factors driving the company in conducting tax aggressiveness (Lietz, 2013).

The company's tax aggressiveness can be calculated through effective tax rate (ETR). If the ETR value is reduced by the negative tax rate, then the company is categorized as doing tax aggressiveness and vice versa (Abdul-Wahab et al., 2017). ETR calculations are divided into three, namely (Hanlon & Heitzman, 2010; Dyreng et al., 2008; Ayers et al., 2009):

GAAP ETR

GAAP ETR is calculated from the total income tax expense divided by total corporate income before tax, so it can show changes in the amount of tax burden in each period. The lower the value of GAAP ETR, the higher the level of tax aggressiveness of the company (Damayanti & Prastiwi, 2017).

Cash ETR (CETR)

CETR is calculated from the tax burden currently paid divided by total income before tax, so that it can show the level of tax aggressiveness of the company through fixed and temporary differences (Harnovinsah & Mubarakah, 2016).

Current ETR (CUETR)

CUETR aims to describe the company's ETR value for the current tax burden so that it can measure a company's tax aggressiveness in the short term. CUETR is calculated by the tax burden which is now divided by total income before tax (Auliadini & Martani, 2013).

Political Connection

Companies with political connections are companies with certain businesses that have a bond or seek relationships with politicians or the government (Tehupuring & Rossa, 2016). Zhang et al., (2012) suggested two different results due to the company's political connections in relation to tax aggressiveness decisions:

Political favoritism effect

Companies are becoming increasingly aggressive in tax evasion because they can lobby the government to avoid tax audits or other actions that may reveal the company's tax aggressiveness.

Bureaucratic incentive effect

The company becomes obedient and compliant to the imposition of taxes because of the bond or control of the government through political connections to evaluate the company so that the company does not dare to carry out tax aggressiveness.

Companies are considered to be politically connected if one of the shareholders (who has ownership voting rights of >10%) or the company leader is an official or a member of parliament, a minister or has close relationship with politicians or political parties (Faccio, 2006; Tehupuring & Rossa, 2016). This study uses the Resource Dependence Theory (RDT) approach proposed by Pfeffer & Salancik (2003) which states that due to uncertainty, companies will take action to manage interdependence between companies and other external parties such as the government. Political connection is a part of the company's strategy to manage uncertainty in its business environment. The existence of parties that have certain political power will provide support for companies in managing the interdependent relationship.

Executive Compensation

Compensation can be interpreted as a form of appreciation given by the company to its employees in order to feel valued (Mayangsari et al., 2015). Compensation addressed to the board of commissioners and directors is referred to as executive compensation. Putri & Lautania (2016) describe executive compensation as a reward given by shareholders to executives as decision makers in order to harmonize the interests of shareholders (principals) with executives (agents) based on a measure of performance in running the company. There are four forms of compensation, namely: basic salary, annual bonus measured from performance, long-term incentives in the form of stock plans or bonuses, and stock options. Executive compensation is part of the agency cost based on agency theory proposed by Jensen & Meckling (2019). The existence of compensation is a cost of supervision for shareholders that aims to enable the executive to act in accordance with the interests of the owner.

Development of Hypothesis

According to Wicaksono (2017), companies that have political connections are proven to have a higher level of tax aggressiveness than companies that do not have political connections. Companies will be bolder in carrying out tax aggressiveness because of the protection of the connections they have so that they have a low risk of detection. Direct access to the central government also makes it easier for companies to lobby the government (Kim & Zhang, 2016). This study adopts the research of Pranoto & Widagdo (2016) and Tehupuring & Rossa (2016) in producing a measuring indicator of a politically connected company, namely where one of the board of commissioners, the board of directors or the shareholders who serves or have served in the company is a former public official, military, or has affiliations with political parties.

H1: Political connections are associated with company tax aggressiveness.

According to Mayangsari et al. (2015), shareholders seek tax efficiency to obtain a high return on investment. The decision-making process related to tax aggressiveness actions of the company is the executive authority of the head of the company. Executives will be willing to make policies in accordance with the interests of shareholders if they benefit from the policies made, so that shareholders provide compensation or reward to executives for them willingness to act in the interests of shareholders (Amri, 2017). This scheme is called the incentive compensation. The research of Armstrong et al. (2015) has proven that incentive compensation can influence the tendency of corporate tax aggressiveness, the greater the incentives given to managers, the greater the tax avoidance the company does. The indicator of measuring executive compensation in this study was adapted from the research of Armstrong et al. (2015), namely total cash compensation received by executives in a year.

H2: Executive compensation is associated with the company's tax aggressiveness.

Research Methodology

This research was conducted at the IDX manufacturing sector companies listed in the period of 2015-2017 which amounted to 163 companies, namely: 72 basic industry sub-sector companies, 46 consumer goods industry sub-sector companies, and 45 miscellaneous industry sub-sector companies (Indonesia Stock Exchange, 2018). The sample included 131 companies (393 observations) taken based on the following criteria(Table 3):

| Table 3 Research Sample |

|

| Number of Companies | 163 |

| Criteria | |

| Companies listed after 2017 | 9 |

| Bookkeeping closing not in December | 3 |

| Illegible/incomplete inancial reports | 2 |

| Companies listed in 2017 | 4 |

| Companies unable to state tax cash payment | 4 |

| Companies not stating executive compensations specifically | 10 |

| Total Sample | 131 |

While the final sample of the company after the outlier data was released were 315 observations.

Operational Definition and Variable Measurement

Political connection

Politically connected companies are companies with certain businesses that have a bond or seek relationships with politicians or the government (Tehupuring & Rossa, 2016). The company is said to have a political connection if one of the leaders or shareholders, including those who served previously, owns at least 10% of shares with voting rights fulfilling one of the criteria below, including:

• Has affiliations with political parties

• Is a former government official/military officer

• Is concurrently serving as a military officer

Political connection variables are measured by dummy variables, which is 1 if they have political connections and 0 if not.

Executive Compensation

Executive compensation is a reward given by shareholders to executives as decision makers in order to harmonize the interests of shareholders (principals) with executives (agents) based on a measure of performance in running the company (Putri & Lautania, 2016). Executive compensation is measured by natural logarithms (Ln) from data on the amount of short-term benefits received by executives in a year.

Tax Aggressiveness

Tax aggressiveness is a more aggressive form of tax avoidance, where the weaker tax regulations on corporate taxation, the more aggressive the company's efforts are in minimizing the tax burden that must be paid (Martinez, 2017). Tax aggressiveness is measured by three proxies, namely GAAP ETR, CETR, CUETR.

Control Variables

This study uses three control variables, namely size, leverage and capital intensity ratio (CIR). Company size describes the ability of companies to perform acts of tax aggressiveness (Zimmerman, 1983; Sari & Adiwibowo, 2017). Leverage will encourage companies to carry out tax aggressiveness (Gupta & Newberry, 1997; Sari and Adiwibowo, 2017). Companies with high CIR will tend to have a low tax burden because of the large depreciation burden (Noor & Sabli, 2012; Putri & Lautania, 2016).

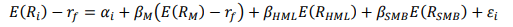

Data Analysis Techniques

This study uses multiple regression analysis to determine the association of political connections and executive compensation to company tax aggressiveness. The form of multiple linear regression analysis in this study is described as follows:

Results

Descriptive statistics from research data are in the following table:

Table 4 shows that the proxies of GAAP ETR, CETR and CUETR used to measure tax aggressiveness in this study have an average value of 0.251, 0.211, and 0.191, respectively. The mean of GAAP ETR is greater than the current corporate tax rate of 25% so it reflects that the company does not carry out tax aggressiveness, as seen from the total income tax burden. The mean value of CETR and CUETR is lower than the current tax rate, so it can be concluded that the company carries out tax aggressiveness as seen from the payment of cash taxes and the current tax burden. The mean and median variables of executive compensation, firm size, leverage, and CIR are relatively similar, indicating that the data is distributed symmetrically.

| Table 4 Descriptive Statistics |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Maximum | Minimum | Standard Deviation | |

| GAAP ETR (Y1) | 0.251 | 0.248 | 17.333 | -3.924 | 1.019 |

| CETR (Y2) | 0.211 | 0.238 | 0.914 | -0.384 | 0.211 |

| CUETR (Y3) | 0.191 | 0.239 | 0.609 | -0.25 | 0.144 |

| Polcon (X1) | 0.469 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.499 |

| Compensation (X2) | 23.167 | 23.208 | 29.083 | 19.141 | 1.396 |

| SIZE (X3) | 28.319 | 28.201 | 33.32 | 21.185 | 1.821 |

| LEV (X4) | 0.501 | 0.454 | 5.056 | 0.000 | 0.477 |

| CIR (X5) | 0.399 | 0.38 | 0.907 | 0.013 | 0.193 |

Table 5 shows the results of data processing for hypothesis testing using multiple linear regression. Based on the table, it can be seen that model 1 GAAP ETR has a statistical significance value of F> of 5%, which means that the model does not meet the model feasibility (Goodness of Fit) so the results of data processing are not used in the discussion. The results in model 2 and model 3 show that H1, which states political connections are associated with tax aggressiveness, is accepted (model 2) and H2, which states that there is an association between management compensation and tax aggressiveness, is accepted (model 2 and model 3). The control variables in this study are company size, leverage, and CIR associated with tax aggressiveness.

| Table 5 Hypothesis Testing Results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| GAAP ETR | CETR | CUETR | |

| C | 1.8223 | 0.1187 | |

| 1.6039 | 0.5450 | 1.0089 | |

| Polcon (X1) | -0.0746 | 0.0433 | 0.0263 |

| -0.5906 | 1.7874* | 1.6064 | |

| Compensation (X2) | -0.0612 | 0.0300 | 0.0187 |

| -1.2098 | 3.0899*** | 2.8509*** | |

| SIZE (X3) | -0.0045 | -0.0177 | -0.0109 |

| -0.1132 | -2.3044** | -2.0967** | |

| LEV (X4) | -0.1807 | -0.1296 | -0.0989 |

| -1.4692 | -5.4973*** | -6.2086*** | |

| CIR (X5) | 0.2528 | -0.1421 | -0.1127 |

| 0.8412 | -2.4661** | -2.8955*** | |

| F-statistic | 1.1561 | 11.7292 | 13.500 |

| Sig F | 0.3307 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.0183 | 0.1595 | 0.1793 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.0024 | 0.1459 | 0.1660 |

Note: *significance level 0.1 or 10%;

**significance level 0.05 or 5%;

*** significance level 0.01 or 1%.

Discussion

Association between Political Connection and Tax Aggressiveness

The results of the study indicate that the existence of political connections decreases tax aggressiveness as reflected by the increase in ETR. The results of this study support the research of Pranoto & Widagdo (2016), which states that political connections negatively affect the company's tax aggressiveness and are in line with the bureaucratic incentive effect which states that political connections can cause companies to be obedient in carrying out their tax obligations and in avoiding tax aggressiveness. Review of the research data show that parties with political connections who hold certain positions in the company are those who have had a career in government and tend to be part of pro-government parties. The existence of these parties encouraged the company to comply with Government tax regulations. Companies must manage interdependence with external parties such as the government in order to overcome uncertainty. Executives who have political connections encourage companies to comply to tax payment regulations to maintain the image of the company in the eyes of the government, which can open opportunities for tax incentives.

Association between Executive Compensation and Tax Aggresiveness

The results showed that executive compensation was positively associated with CETR and CUETR. This means that executive compensation reduces the company's tax aggressiveness. Giving compensation to executives aims to improve company performance. Executives who get high compensation will be burdened with high performance targets and high profit achievement will also bear an increase of tax burden. In addition, executive compensation also describes the work risks that must be borne by the executive. Mistakes in decision making not only cause executives to not get maximum compensation but can potentially cause them to lose their position as corporate executives. This encourages corporate executives to be more careful in making decisions and in minimizing counterproductive decisions in the future including tax aggressiveness. The executive does not only risk losing his position if the tax aggressiveness violates applicable tax regulations but can also be subject to legal sanctions as a party responsible for the company.

Association between Size, Leverage, and CIR to Tax Aggressiveness

This study uses three control variables, namely size, leverage, and CIR. The results show that the three control variables were negatively associated with tax aggressiveness. This means that the bigger the size, leverage, and CIR of the company, the lower the ETR of the company or the higher the tax aggressiveness of the company. This shows that the company's decision to carry out tax aggressiveness is based more on the company's fundamental factors such as company size, capital structure, and corporate asset structure.

Conclusion

Based on the results of data processing and discussion, it was concluded that political connections and management compensation were negatively associated with tax aggressiveness. This is indicated by the positive association between political connections and executive compensation with ETR. While the company's fundamental factors are positively associated with tax aggressiveness. The implication of this research is that the existence of political connections can bring benefits to both the company and the government. For companies, the existence of political connections provides a good image for the company by encouraging companies to comply with their tax obligations and to reduce the actions of tax aggresiveness. Whereas for the government, the existence of political connections in the company can bring benefits because of the potential to increase state revenues from the taxation sector by reducing the practices of tax aggressiveness in the company. In addition, providing high executive compensation can also encourage companies to comply with tax regulations so that companies avoid taxation problems arising from tax aggressiveness.

References

Abdul-Wahab, A., Ariff, A.M., Marzuki, M., & Mohd-Sanusi, Z. 2017. Political connections, corporate governance and tax aggressiveness in Malaysia. AsianReviewof Accounting, 25(3), 424-451.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Amri, M. (2017). The effect of management compensation on tax avoidance with moderation of directors' gender diversification and corporate executive risk preference in Indonesia. Jurnal Akuntansi Riset, 9(1), 1-14.

Armstrong, C.S., Blouin, J.L., Jagolinzer, A.D., & Larcker, D.F. (2015). Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance.Journal of Accounting and Economics,6(1), 1-17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Auliadini, A., & Martani, D. (2013).Analysis of effective tax rate and book tax difference based on industry sector (Empirical study of companies listed on the IDX for the period 2009-2011).

Ayers, B.C., Jiang, J., & Laplante, S.K. (2009). Taxable income as a performance measure: The effects of tax planning and earnings quality.Contemporary Accounting Research,26(1), 15-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ayu, WS, Nasir, A., & Rusli, R. Effects of liquidity, earnings management, independent commissioners and executive compensation on tax aggressive (Empirical studies on banking companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange Period 2014-2015).Student Online Journal (JOM) in the Field of Economics,4(2), 1-15.

Cobham, A., & Janský, P. (2018). Global distribution of revenue loss from corporate tax avoidance: re?estimation and country results.Journal of International Development,30(2), 206-232.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Damayanti, HH, & Prastiwi, D. (2017).OECD's role in minimizing tax aggressiveness in multinational companies.Journal of Multiparadigm Accounting,8(1), 79-89.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dyreng, S.D., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E.L. (2008). Long?run corporate tax avoidance.The Accounting Review,83(1), 61-82.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Faccio, M. 2006. Politically connected firms. The American Economic Review, 369-386.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fisman, R. (2001). Estimating the value of political connections.American Economic Review,91(4), 1095-1102.

Gupta, S., & Newberry, K. (1997). Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates: Evidence from longitudinal data.Journal of Accounting and Public Policy,16(1), 1-34.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hanlon, M., & Heitzman, S. (2010). A review of tax research.Journal of accounting and Economics,50(2-3), 127-178.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harnovinsah, H., & Mubarakah, S. (2016). Dampak tax accounting choices terhadap tax aggressive.Jurnal Akuntansi,20(2), 267-284.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harymawan, I. (2018). Why do firms appoint former military personnel as directors? Evidence of loan interest rate in militarily connected firms in Indonesia.Asian Review of Accounting,26(1), 2-18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jensen, M.C., & Meckling, W.H. (2019). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. InCorporate Governance(pp. 77-132). Gower.

Kim, C., & Zhang, L. (2016). Corporate political connections and tax aggressiveness.Contemporary Accounting Research,33(1), 78-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lietz, G.M. (2013). Tax avoidance vs. tax aggressiveness: A unifying conceptual framework.Tax Aggressiveness: A Unifying Conceptual Framework.

Martinez, A.L. (2017).Tax aggressiveness: A literature survey.Journal of Accounting Education and Research,11.

Mayangsari, C., Zirman, Z., & Haryani, E. (2015).Effect of executive compensation, executive share ownership, executive risk preference and leverage on tax avoidance.Student Online Journal (JOM) in the Field of Economics,2(2), 1-15.

Noor, R.M., & Sabli, M. (2012). Tax planning and corporate governance. InInternational Conference on Business and Economic Research (3rd ICBER) Proceeding.

OECD. (2017). Global revenue statistics database.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G.R. (2003).The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Stanford University Press.

Putri, C.L., & Lautania, M.F. (2016).The effect of capital intensity ratio, inventory intensity ratio, ownership structure and profitability on the effective tax rate (ETR) (Study of manufacturing companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange in 2011-2014).Scientific Journal of Accounting Economics Students,1(1), 101-119.

Pranoto, B.A., & Widagdo, A.K. (2016).The influence of political connections and corporate governance on tax aggressiveness.

Tehupuring, R.R., & Rossa, E. (2016).The influence of political connections and audit quality on tax avoidance practices in banking institutions registered on the Indonesian capital market for the 2012-2014 period.InIndocompac National Seminar.Bakrie University.

Wicaksono, A.P.N. (2017).Political connections and tax aggressiveness: Phenomena in Indonesia.Accountability,10(1), 167-180.

Ying, T., Wright, B., & Huang, W. (2017). Ownership structure and tax aggressiveness of Chinese listed companies.International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 25(3), 313-332.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhang, H., Li, W., & Jian, M. (2012). How does state ownership affect tax avoidance? Evidence from China.Singapore Management University, School of Accountancy, 13-18.

Zimmerman, J.L. (1983). Taxes and firm size.Journal of Accounting and Economics,5, 119-149.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. ASMJ-23-13260; Editor assigned: 16-Jan-2023, PreQC No. ASMJ-23-13260(PQ); Reviewed: 23-Jan-23, QC No. ASMJ-23-13260; Revised: 28-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. ASMJ-23-13260(R); Published: 02-Feb-2023