Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Authentic Leadership and its Interactions with Compassion and Humility of Employees

João M. Lopes, University of Beira Interior

Tânia Santos, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria & CICS, NOVA - Interdisciplinary

Center for Social Sciences of the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences (FCSH/NOVA)

Márcio Oliveira, University of Beira Interior

Sofia Gomes, University Portucalense & REMIT - Research on Economics

Marlene Sousa, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria & CICS.NOVA - Interdisciplinary Center for Social Sciences of the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences (FCSH/NOVA)

Keywords:

Authentic Leadership, Humility, Compassion

Abstract

By the increasing recognition that the scientific and practical communities attribute humility and compassion as influencing organisational performance, this study aims to understand whether the exercise of authentic leadership influences these constructs. For this purpose, using a quantitative study, a questionnaire was applied to employees of small and medium-sized Portuguese companies who are directly subordinated to the top management of these companies in the course of their professional activity.

This research empirically validates the theoretical arguments that suggest that authentic leadership is related to humility and compassion (the latter, measured based on the dimensions of kindness, common humanity, full attention, indifference, detachment and separation) and demonstrates that subordinates are essential resources to help organisations face competitive challenges, taking advantage of their employees' potential and promoting organisational efficiency and competitive advantages over the competition.

Introduction

The construct of humility has received increasing attention in studies on organisations, with some research on the importance and contribution of humility in organisational performance (Owens et al., 2013; Owens & Hekman, 2012; Vera & Rodriguez-Lopez, 2004). This assumes an increasingly prominent role in organisations, as it is a strategic virtue for all organisations in any sector because it becomes a competitive advantage: it is a valuable resource, rare, irreplaceable and difficult to imitate (Vera & Rodriguez-Lopez, 2004). As a characteristic with increasing relevance in organisations, it is important to understand its antecedents and what factors may influence it.

Compassion is also assuming an increasingly important role in the organisational environment as it can reset the energy levels of organisational members and make them feel valued (Choi et al., 2016).

Since leadership is a very relevant contextual factor, it is important to study how the characteristics of the leader and his/her specific behaviour may support, suppress, facilitate, or inhibit certain characteristics of the employees, such as humility and compassion. In this study, we intend to understand whether authentic leadership positively influences the humility of employees and whether compassion, in this same target group, may be a mediating variable between authentic leadership and humility.

Thus, this study seeks to enrich the research and deepen the literature on this topic, looking at humility as a very relevant virtue in the business world. The aim is to understand whether authentic leadership and compassion among employees can influence this humility construct, which is becoming increasingly important.

The article is structured as follows: the next section discusses the arguments that lead to the formulation of hypotheses; the third and fourth sections present the methods and results, respectively; and the final section discusses the main conclusions and considers the limitations of the research and suggestions for future research.

Literature Review

The Different Constructs: Authentic Leadership, Humility and Compassion

In recent years the impact of Authentic Leadership (AL) on employees has aroused great interest in both practitioners (George et al., 2007) and academics, who argue that AL promotes positive attitudes and behaviours in subordinates and contributes to better organisational performance (Rego et al., 2012).

AL is built on authenticity, referring to situations where individuals act according to their values, beliefs and ultimately human nature, even when under various pressures that are difficult to deal with. Authentic leaders express their true selves to their followers, acting according to their internal reality and away from any hypocrisy and lack of sincerity (Otaghsara & Hamzehzadeh, 2017).

Also, Avolio, et al., (2004) state that authentic leaders know who they are, know what they believe and value, and act on those values and beliefs when interacting transparently with others.

AL is made up of four dimensions: (1) Self-awareness, which is about understanding one's strengths and weaknesses and the multifaceted nature of oneself, being aware of one's impact on other people; (2) Relational Transparency, which refers to presenting one's authentic self to others; (3) Internal Moral Perspective, which is a form of internal and integrated self-regulation guided by internal moral standards and values rather than due to organisational or societal pressures, resulting in decision making and behaviour that is consistent with these internal values; (4) Balanced Information Processing, which translates into objectively analysing data before making decisions, soliciting views that question one's deeper positions (Avolio et al., 2004; Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2008).

Avolio, et al., (2004) consider that LA is the basis for building trust, helping people develop their strengths and be more positive, open their thinking, add value and meaning about what is right in decisions, and improve the overall performance of the organisation over time.

Regarding the concept of humility, we can state that it was widely studied by philosophers and theologians in antiquity, having lost some lustre in the modern era. But in recent years, new theoretical and empirical approaches in psychology and business ethics have treated humility not as a weakness but as a strength, emphasising its contribution to organisational cohesion and trust building (Argandona, 2015).

According to De Bruin (2013), humility can be seen as an "epistemic" virtue that leads a person to be aware of his/her reliability. What characterises a humble person is their self-knowledge of themselves and the intention with which they assess or judge themselves (Argandona, 2015).

Humility involves the ability to evaluate success, failure, work and life without exaggeration. It allows individuals to distinguish the delicate line between good characteristics such as healthy self-confidence, self-esteem and self-evaluation and less positive ones such as overconfidence, narcissism and stubbornness (Vera & Rodriguez-Lopez, 2004).

The construct of humility can be defined as an interpersonal characteristic that emerges in social contexts and encompasses three dimensions: (1) willingness to know oneself accurately; (2) appreciation of others; (3) willingness (availability) to learn from others (Owens et al., 2013).

In the organisational context, humility is important because it increases the ability of companies to understand and respond to external threats and opportunities, allowing them to achieve outstanding performance and being a source of competitive advantage (Vera & Rodriguez-Lopez, 2004).

Regarding compassion, this is a relatively new concept in social and clinical psychology, and studies involving organisations are still scarce (Raes et al., 2011). However, its importance in the business world is becoming increasingly evident.

Compassion can be defined as the ability of an individual to be sympathetic to another's suffering, feeling affected by their pain without avoiding or abandoning it, expressing feelings of kindness and caring for that person to alleviate their suffering (Neff, 2003; Neff et al., 2008).

This definition encompasses three components: (1) kindness, which translates into the ability to be kind and understanding towards another's suffering, rather than being indifferent and neglectful; (2) common humanity, which means understanding that one's own experiences are part of a shared human experience, as opposed to disengagement; (3) mindfulness, which translates into balanced awareness, acceptance and openness towards another's suffering, not denying or avoiding contact with another's negative affect (Neff, 2003; Raes et al., 2011).

The Relationship between the Different Constructs

Many authors consider that AL greatly influences employees' behaviour, contributing to improving their creative performance, increasing their hope for the future, their commitment and meaning at work, and fostering a structure and environment that supports both leaders and their followers (Anwar et al., 2020; Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Malik & Dhar, 2017; Mubarak & Noor, 2018). Avolio & Gardner (2005) consider that the authentic leader can impact subordinates' behaviour through positive modelling, emotional contagion and positive social communication exchanges.

In this way, and through emotional contagion, authentic leaders foster compassion in their employees, as they help people frame the meaning of suffering and a model and anchor appropriate acts of compassion (Dutton et al., 2014). Some authors (Banker & Bhal, 2020; Rynes et al., 2012) suggest that leadership is crucial to the creation of a compassionate organisation, as it is the leader's responsibility to align and embed moral values in the organisation and in the behaviours of their subordinates to ensure that compassion circulates throughout the organisation.

Compassion cannot be exercised in isolation and is rooted in the value system (organisational and individual), which leads us to assume that authentic leaders have an important role in fostering it throughout the organisation. Authentic leaders, who have strong empathy for their employees, can successfully build a culture of compassion by rooting ethical/moral virtues in people, creating a workplace conducive to building trust in the organisation (Banker & Bhal, 2020). These leaders can also create quality bonds between members of the organisation, which leads to a greater climate of compassion among all (Dutton et al., 2014).

In this way, we can assume that: authentic leadership positively impacts employees' compassion (H1).

Fredrickson (1998) highlights the positive effect that compassion has on employees: they feel valuated as human beings and not mere human resources, increasing their levels of commitment and belonging to the organisation and their levels of humility.

Also, Kanov, et al., (2004) suggest that when compassion is disseminated in organisations, becoming a collective phenomenon, it can make other virtues, such as collective processes of forgiveness, integrity, humility and wisdom, collective.

Engen & Singer (2015) argue that employees who experience higher levels of compassion tend to have more positive and beneficial feelings towards the organisation, reducing anxiety, stress, intention to leave the organisation and burnout. Thus, by having high levels of compassion, employees feel willing to know themselves accurately, appreciate others, and learn from them, leading us to infer that employees with compassion are also humble employees.

We can then hypothesise that: compassion positively impacts humility (H2).

May, et al., (2003) argue that authentic leaders are humble and less likely to feel the need to demand someone's attention since LA has points in common with humility. Some authors (Owens & Hekman, 2016; Rego et al., 2017) refer that leaders' humility is contagious and, therefore, we can infer that authentic leaders, by being humble, also foster the humility of their employees.

This relationship may be mediated by compassion, as authentic leaders, fostering compassion in their subordinates, are also positively influencing their humility (Engen & Singer, 2015; Kanov et al., 2004).

Thus, we can hypothesise that: authentic leadership positively impacts employee humility when mediated by compassion (H3).

Data and Methodology

Sample

The sample consists of 109 observations collected through an online questionnaire applied to employees of small and medium-sized companies in the central region of Portugal, registered as members of NERLEI (Business Association of the Leiria Region). They play the role of direct subordination to the top management of these companies. Data were collected between 2 January and 1 March 2021 through the Google Forms application. The questionnaire contains 16 questions on authentic leadership, corresponding to the scale of Rego, et al., (2012), 24 questions on compassion, according to the scale of Raes, et al., (2011), having adopted the version adapted to the Portuguese adult population proposed by Vieira, et al., (2013), and nine questions on humility measured by the scale of (Owens et al., 2013). Some sociodemographic variables were also collected, such as age, gender, seniority in the company, and years of collaboration with the current leader. All variables, except for the sociodemographic variables, were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 - never to 5 - often was used in authentic leadership, 1 - the statement does not strictly apply at all to me to 5 - the statement applies completely to me, and 1 - almost never, if not never to 5 - almost always, if not always, was used in compassion.

The respondents in the sample are mainly female Portuguese workers (57.8%), and the average age of the sample is 36.9 years. They have worked for less than ten years in the current company and have been under the leadership of the current company leader for more than two years but less than five years.

Structural Model and Hypotheses Under Study

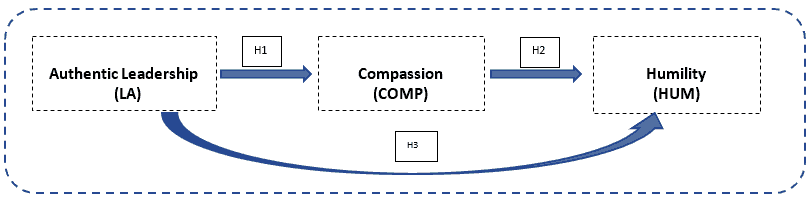

The main objective is to analyse the impact of authentic leadership on humility mediated by compassion. The theoretical structural model was built and is shown in Figure 1.

According to this model, authentic leadership has a direct impact on compassion (Banker & Bhal, 2020; Kanov et al., 2004; Rynes et al., 2012) and an indirect impact on humility (Engen & Singer, 2015; Owens & Hekman, 2012; Rego et al., 2017). Compassion directly impacts humility (Engen & Singer, 2015; Kanov et al., 2004). Thus, the following hypotheses were formulated (Figure 1). In the theoretical structural model, the three hypotheses under study are represented, where: H1 - Authentic leadership positively impacts employees' compassion; H2 - Compassion positively impacts humility; and H3 - Authentic leadership positively impacts employee humility when mediated by compassion.

Methodology

Given that the data were collected through a questionnaire, one of their characteristics is that they do not have a normal distribution. On the other hand, many indicators associated with each of the latent variables were collected. As such, it is necessary to test the significant relationships between the indicators and the latent variables and between latent variables. Thus, as in other studies on this topic, a quantitative methodology was used to enhance the relationships between the latent variables and replicate the methods and techniques for other samples, as Nikam, et al., (2019) suggested.

Given the characteristics of the sample (small sample size, no normal distribution of data, many indicators and structural paths between latent variables), we used the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method, which application and purpose is in line with the characteristics of our sample (Ringle et al., 2015). PLS is a variance-based method with the basic assumption of the non-normal distribution of data, combining regression estimation with factor analysis (Ringle et al., 2019; Hair et al., 2019).

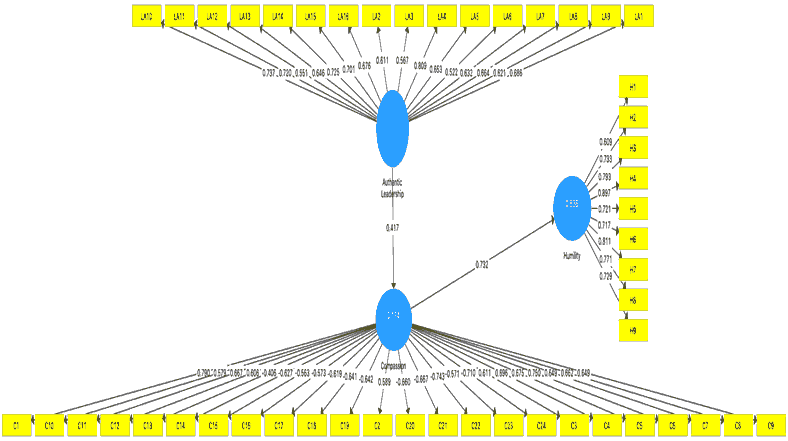

The first step is to estimate the theoretical structural model with the application of the PLS algorithm that, from a sequence of regressions, makes the weight vectors converge to a single optimal point, according to Ringle, et al., (2015), which resulted in the model shown in Figure 2.

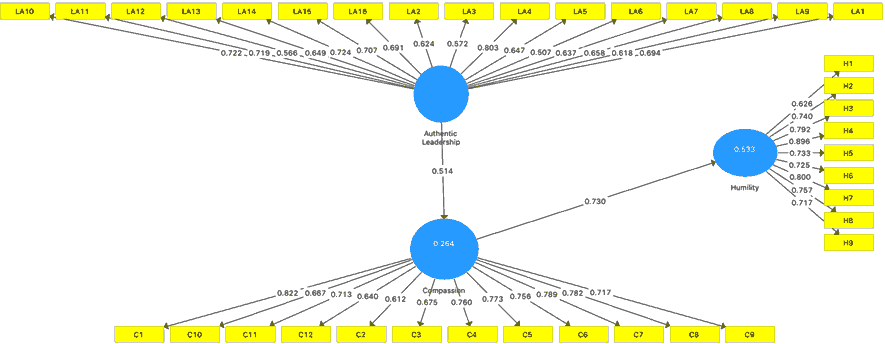

The three latent variables (authentic leadership, humility and compassion) are represented in the circles and the indicators represented in the rectangles (49 indicators). The outer loadings are the structural paths between the indicators and the latent variables, with a reference value of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2019), to be significant. Through the analysis of the model shown in Figure 2, we observed that the indicators measuring compassion C13 to C24, referring to the dimensions of compassion indifference (C13 to C16), disengagement (C17 to C20) and non-engagement (C21-C24), have outer loadings lower than 0.50. Thus, these indicators were removed from the sample to calibrate the model. The Global-Minimum Error Uninformative-Variable-Elimination for PLS method was used as suggested by Andries et al. (2017). Thus, the total number of latent variable indicators used for model estimation is 37, and we obtained, after applying the PLS algorithm, the estimated model shown in Figure 3.

Internal Consistency and Predictive Accuracy of the Model

The model presented in Figure 3 is "satisfactory to good" in terms of internal consistency because the composite reliability and Cronbach's Alpha values should, according to Hair et al. (2019), be greater than 0.70; the outer loadings (structural paths between the indicators and the latent variables shown in Figure 3) and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be greater than 0.50, as verified in our model. Summary of the internal consistency indicators in Table 1.

| Table 1 Indicators Of Internal Consistency Of The Model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic leadership | Compassion | Humility | |

| Cronbach's Alpha | 0.915 | 0.918 | 0.905 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.925 | 0.931 | 0.923 |

| Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | 0.539 | 0.530 | 0.573 |

The discriminant validity of the latent variables was also assessed by applying the Fornell-Larcker criterion whereby each AVE of the latent variables (elements on the main diagonal that are in bold) should be greater than all the square correlations of the latent variables (off-diagonal elements), as found in this model (Table 2).

| Table 2 Results Of The Application Of The Fornell-Larcker Criterion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic Leadership | Compassion | Humility | |

| Authentic Leadership | 0.762 | ||

| Compassion | 0.514 | 0.728 | |

| Humility | 0.570 | 0.720 | 0.757 |

The R2 is used to assess the model's predictive accuracy and is marked in Figure 3 for the endogenous latent variables compassion (R2=0.264) and humility (R2=0.533). According to Cohen (1988), for the social sciences, this model has an R2 medium (between 0.15 and 0.35) for the compassion latent variable and an R2 high (greater than 0.35) for the latent humility variable.

We conclude that the estimated model in Figure 3 meets the criteria of internal consistency and predictive accuracy.

Analysis and Discussion of Results

After validating the model, the next step is to estimate the relationships between latent variables at a 95% confidence interval. For this purpose, the bootstrap technique was applied in Smart PLS, according to Ringle et al. (2015). The results of the application of this technique are shown in Table 3.

| Table 3 Significance Testing Results Of The Structural Model Path Coefficients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

| H1: Authentic Leadership -> Compassion | 0.514 | 0.547 | 0.061 | 8.394 | 0.000 |

| H2: Compassion -> Humility | 0.730 | 0.744 | 0.050 | 14.709 | 0.000 |

| H3: Authentic Leadership -> Humility | 0.375 | 0.408 | 0.058 | 6.455 | 0.000 |

We can thus conclude that authentic leadership positively impacts compassion (?=0.514), confirming H1. That is, a 1% change in compassion causes a 51.4% positive change in authentic leadership. These findings are in line with the contributions of Banker & Bhal (2020); Rynes, et al., (2012); Dutton, et al., (2014).

It was also possible to see that compassion positively impacts humility (?=0.730), confirming H2. A 1% change in humility has a 73% positive impact on compassion. These findings find an echo in the studies of Fredrickson (1998); Kanov, et al., (2004); Engen & Singer (2015).

Finally, it was found that authentic leadership positively impacts humility (?=0.375), confirming H3. A 1% change in humility has a positive impact of 37.5% on authentic leadership. These results are in line with the contributions of May, et al., (2003); Owens & Hekman (2016); Rego, et al., (2017); Engen & Singer (2015); Kanov, et al., (2004).

We thus conclude, for p=0.000, that authentic leadership has a direct positive impact on compassion and an indirect positive impact on humility; compassion has a direct positive impact on humility.

Conclusions, Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

The great changes in economic, social, political, cultural and ethical relations that the world is going through impose new conditions on organisations and reconfigure every day the world of work and business. In this context, new values and principles emerge, and concepts that, until some time ago, would have been considered peripheral now assume a central role in organisational performance and in the way organisations are led. In this study, the influence of authentic leadership in promotion of values such as humility and compassion in a business context was assessed.

It was possible to see that humility and compassion are becoming more and more important in our society due to the constant changes caused by the growing competition among organisations, being essential that their leaders provide conditions for developing these characteristics among employees.

In general, we can affirm that our research showed that authentic leaders awaken more humility and compassion in their subordinates. These findings assume scientific relevance since they reinforce other studies that we found and point to a direct influence of authentic leadership on the variables under study. On the other hand, this research provides interesting results that can be applied in organisational contexts, at the time of decision-making, concerning the development of employees' capabilities for individual and collaborative performance.

As for the research limitations, the first limitation refers to the fact that the dependent and independent variables were collected simultaneously and from the same source. We suggest using longitudinal studies in the future, with data concerning the dependent and independent variables being collected at different moments in time.

On the other hand, our study does not predict the influence of different individual employee characteristics on the levels of humility and compassion. We consider that leaders can influence these characteristics of their employees, but still, we do not measure the influence that individual employee characteristics have on these variables.

Funding

This work is supported by national funds, through the FCT—Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the project UIDB/04630/2020.

References

- Andries, J., Heyden, Y., & Buydens, L. (2017). Improved variable reduction in partial least squares modelling by Global-Minimum Error Uninformative-Variable Elimination. Analytica Chimica Acta, 982, 37-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2017.06.001.

- Anwar, A., Abid, G., & Waqas, A. (2020). Authentic leadership and creativity: Moderated meditation model of resilience and hope in the health sector. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(1), 18–29.

- Argandona, A. (2015). Humility in management. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(1), 63–71.

- Avolio, B.J., & Gardner, W.L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338.

- https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

- Avolio, B.J., Gardner, W.L., Walumbwa, F.O., Luthans, F., & May, D.R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 801–823. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003

- Banker, D.V., & Bhal, K.T. (2020). Understanding compassion from practicing managers’ perspective: Vicious and virtuous forces in business organizations. Global Business Review, 21(1), 262–278.

- Choi, H.J., Lee, S., No, S.R., & Kim, E.Il. (2016). Effects of compassion on employees’ self-regulation. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44(7), 1173–1190.

- De Bruin, B. (2013). Epistemic virtues in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(4), 583–595.

- Dutton, J.E., Workman, K.M., & Hardin, A.E. (2014). Compassion at work.

- Engen, H.G., & Singer, T. (2015). Compassion-based emotion regulation up-regulates experienced positive affect and associated neural networks. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(9), 1291–1301.

- Fredrickson, B.L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319.

- George, B., Sims, P., McLean, A.N., & Mayer, D. (2007). Discovering your authentic leadership. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 129.

- Hair, H.J., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling, (2nd edition). Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA. ISBN 978-1-4833-7744-5.

- Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C.M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Kanov, J.M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M.C., Dutton, J.E., Frost, P.J., & Lilius, J.M. (2004). Compassion in organizational life. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 808–827.

- Malik, N., & Dhar, R.L. (2017). Authentic leadership and its impact on extra role behaviour of nurses. Personnel Review, 46(2), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2015-0140

- May, D.R., Chan, A.Y.L., Hodges, T.D., & Avolio, B.J. (2003). Developing the moral component of authentic leadership. Organizational Dynamics.

- Mubarak, F., & Noor, A. (2018). Effect of authentic leadership on employee creativity in project-based organizations with the mediating roles of work engagement and psychological empowerment. Cogent Business \& Management, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1429348

- Neff, K.D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

- Neff, K.D., Pisitsungkagarn, K., & Hsieh, Y.P. (2008). Self-compassion and self-construal in the United States, Thailand, and Taiwan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(3), 267–285.

- Nikam, V., Abimanyu, J., & Suresh, P. (2019). Quantitative methods for social sciences, NIAP, New Delhi. ISBN: 978-81-940080-2-6

- Otaghsara, S.M.T., & Hamzehzadeh, H. (2017). The effect of authentic leadership and organizational atmosphere on positive organizational behavior. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics, 4(11), 1122–1135.

- Owens, B.P., & Hekman, D.R. (2012). Modeling how to grow: An inductive examination of humble leader behaviors, contingencies, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 787–818.

- Owens, B.P., & Hekman, D.R. (2016). How does leader humility influence team performance? Exploring the mechanisms of contagion and collective promotion focus. Academy of Management Journal, 59(3), 1088–1111.

- Owens, B.P., Johnson, M.D., & Mitchell, T.R. (2013). Expressed humility in organizations: Implications for performance, teams, and leadership. Organization Science, 24(5), 1517–1538.

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K.D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255.

- Rego, A., Owens, B., Leal, S., Melo, A.I., Cunha, M.P., Gonçalves, L., & Ribeiro, P. (2017). How leader humility helps teams to be humbler, psychologically stronger, and more effective: A moderated mediation model. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(5), 639–658.

- Rego, A., Sousa, F., Marques, C., & e Cunha, M.P. (2012). Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. Journal of Business Research, 65(3), 429–437.

- Ritchey, F. (2008). The statistical imagination: Elementary statistics for the social sciences, (2nd edition). McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA.

- Rynes, S.L., Bartunek, J.M., Dutton, J.E., & Margolis, J.D. (2012). Care and compassion through an organizational lens: Opening up new possibilities. Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY.

- Vera, D., & Rodriguez-Lopez, A. (2004). Strategic virtues: Humility as a source of competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 393–408.

- Vieira, C., Castilho, P., & Duarte, J. (2013). Study of the validation and measurement of the portuguese version of the compassion scale. Coimbra University.

- Walumbwa, F.O., Avolio, B.J., Gardner, W.L., Wernsing, T.S., & Peterson, S.J. (2008). Authentic leadership: development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126.