Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Breaking Silence and Improving Performance: How Subordinates Feeling Trusted, and Loyalty towards Supervisors Mediates the Relationship between Ethical Leadership and Project Team Members Silence

Kanwal Iqbal Khan, Institute of Business & Management, University of Engineering and Technology

Saima Saleem, Institute of Quality & Technology Management, University of the Punjab

Muhammad Sheeraz, Air University School of Management, Air University Islamabad

Umaila Imtiaz, Institute of Business & Management, University of Engineering and Technology

Keywords

Ethical Leadership, Project Team Members’ Silence, Subordinate Feeling Trusted, Loyalty Towards Supervisors, Emotional Instability, Project Success, Mental Health.

Abstract

Communication is considered a crucial phenomenon for the project success, but due to the silent behaviour of team members, it becomes challenging to complete the project according to the plan, and delay in it eventually leads to the failure of the project. Silence further leads to severe health consequences, including stress, emotional instability, and trust issues. Therefore, the management needs to pay special attention to this issue and resolve it by motivating team members to break up the silence and share their concerns. This study aims to examine the impact of ethical leadership in dealing with the silent behaviour of project team members through the mediating role of subordinate feeling trusted and loyalty towards their supervisor. Data were collected from 334 team members involved in the construction projects. Consistent with the literature, results confirm that ethical leadership reduces the silence of project team members (Acquiescent; Defensive; Prosocial). The findings also elaborate that the relationship between ethical leadership and project team members’ silence (Acquiescent; Defensive; Prosocial) is partially mediated by the subordinates feeling trusted and loyalty towards supervisor. These results suggest that project managers should adopt an ethical leadership style to prevent the silent behaviour of project team members, which will support the successful execution of projects.

Introduction

The project success depends on the coordination among the teams, where all members have to work to-gether to achieve a common goal (Bubshait et al., 2015). The team members may belong to diversified cultures, groups, fields, disciplines, backgrounds or management levels, which can be beneficial for accomplishing the project. But sometimes, it creates a lack of communication that causes conflicts among the team members (Joshi & Roh, 2009). This situation further leads to the silent behaviour of the employees, which influences the execution of the projects (Ekrot et al., 2016). Silence of employees occurs when they retain any information, opinion or ideas related to the organizational circumstances from experts, coworkers, and managers perceived to affect the change and important for the decision making (Van Dyne et al., 2003). When team members have a voicing concern at a workplace, it is trivial to share their opinions and suggest work-related tasks about controversial and emerging problems (Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison & Milliken, 2000). It can negatively affect their mental health and become a major reason for stress that influences their individual and overall project performance (Dedahanov et al., 2016). Therefore, organizations try to deal with the voicing concerns of the employees to avoid the negative conse-quences of their silence.

Employee silence has recently attracted the attention of many researchers and practitioners in the context of organizational studies because communication is one of the critical factors that affect the success of the organization (Nechanska et al., 2020). Still, it requires more attention in the project management field because communication without hindrance is inevitable for project success (Demirkesen & Ozorhon, 2017). In the project settings, the distinct characteristics of team members are required. Their knowledge, experience, expertise, and attitude towards assigned task affect the overall project performance (Wu et al., 2017). They have to face uncertainties, skillfully adjust the available resources and avail chances by examining outcomes during project life cycles (Detert & Burris, 2007). Therefore, the team members' cooperation is necessary at every stage. If they intentionally withhold any information, then the process of facts gathering, examining, and sharing is slow down, which causes a delay in decisions (Ekrot et al., 2016). Silent behaviour further leads to stress, frustration, lack of interest. When people cannot speak up their opinions, thoughts and ideas, it creates dissatisfaction which converts into stress, frustration and depression (Dedahanov et al., 2016).

Previous studies reported that different leadership styles could help to reduce the unusual silent behaviour of employees because leadership styles motivate them even to perform complex tasks (Toor & Ofori, 2008). Specifically, the ethical leadership style helps to deal with the silent behaviour of employees. Ethical leaders promote fair conduct at the workplace and believe in participative management. They involve their subordinates in decision-making, which morally obligates them to reciprocate the same behaviour towards their leaders and share information [8]. According to the previous studies, ethical leadership is negatively related to work-related stress, employee turnover intention and counterproductive work behaviour (Schwepker & Dimitriou, 2021). Therefore, it is appropriate to break the silent behaviour of project team members and reduce stress, depression, and frustration, but this relationship is less studied in the literature (Brinsfield & Edwards, 2020).

Prior studies are evident that trust behaviour among employees significantly impacts the leader-member relationship (Skiba & Wildman, 2019). Feeling trusted is a positive perception of the individual when he/she is feeling trusted by others (Lau et al., 2007). It positively affects the team members' performance in a project management context, resulting in an improved team performance that leads to project success (Buvik & Rolfsen, 2015; Mahmood et al., 2017). When the employees feel trusted by their leaders, they can easily break the silent behaviour and freely communicate important information about the projects. Trust strengthens the leader-member relationship and stimulates the loyalty of employees towards their leaders. That is why it is considered as one of the antecedents of loyalty. Loyalty reflects the commitment of an employee towards the specific leader or person (Farh et al., 1998).

Loyal employees think they should follow their leaders with more commitment no matter how difficult they have to perform (Farh & Cheng, 2000). So, subordinate feeling trusted leads towards loyalty, which help to break the silence of the project team members. Therefore, this study investigates the intervening role of subordinate feeling trusted and loyalty towards the supervisor to know how these constructs help the ethical leaders to reduce the silence of project team members. Specifically, it intends to explain the influence of ethical leadership on project team members’ silence. By definition, ethical behaviour stimulates employees to interact with their leaders and positively contribute to the project success. Therefore, it enlightens the mediating effects of subordinate feeling trusted and loyalty towards the supervisor in the prior relationship.

This study contributed to the literature on project management. It will help managers to understand and break the behaviour of silence of project team members. It will also help managers adopt the ethical leadership style to create a trustworthy environment and make their employees loyalty, which will decrease the silent behaviour. By doing this, communication will get stronger, and information will constantly reach the authorities to be able to use it for improving decision-making. This paper also addresses the problematic situations that project managers face due to employees' silent behaviour and highlights the negative health consequences of silent behaviour; through this, it also contributes to the field of applied psychology.

Literature Review

Ethical Leadership and Project Team Members’ Silence

Ethical leadership demonstrates normatively appropriate conduct of the leaders through their actions and interpersonal skills that establish a positive relationship with followers, promoting two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (Brown et al., 2005). Such a predominant code of conduct is involved in the working environment of ethical leadership, with which representatives feel excited to put their endeavours with inspiration and commitment (Piccolo et al., 2010). Compared to the other forms of leaders, ethical leaders are more open to their employees, and their expectations are more apparent to the employees, i.e., how employees understand the expectations of the organization they work in and the expectations of society clearly (Brown et al., 2005). Therefore, in return, the employees' commitment to the organization increases (Kalshoven et al., 2011).

A leadership role is vital in project success because projects are often designed for a limited duration (Banihashemi et al., 2017). It helps to keep the team members motived and in line with the goals (Tyssen et al., 2014). Many leadership styles like ethical, transformational and authentic leadership motivate employees to perform even complex tasks during the project execution (Toor & Ofori, 2008). According to prior studies, social exchange theory explains ethical leadership and employees’ behavior (Zagenczyk et al., 2020). They investigated that followers of ethical leader consider themselves in a social exchange relationship, and in return, they reciprocate through their better performance (Brown et al., 2005). Kliem (2004) proposes that project management must strengthen ethical conduct in all settings with employees and diminish or dispose of any circum-stances that might strengthen unethical conduct in project tasks. He also suggested that the project manager is answerable for developing a good environment, and he/she should uplift responsibility for outcomes. When employees do not speak up due to fear, low self-efficacy or self-defense, they experience dissatisfaction which ends in work stress, employee turnover intention and counterproductive work behaviour. At this point, leaders can assist the employee in reducing their stress. Ethical leadership is not only needed to break the silent behaviour but also helps to reduce the stress which is caused by silence (Schwepker & Dimitriou, 2021).

Acquiescent silence is defined as purposeful inactive and uninvolved behaviour as an employee who does not express his/her ideas for change. He/she believes that speaking up is pointless, or an employee might withhold opinions and information based on low self-efficacy assessments about the personal capability to affect the situation. In contrast, these conditions present silence as the result of the resignation. In this type of silence, the individual is unwilling to speak up because of the belief that his/her opinion is futile. When employees are not aware of their silence, they show unwillingness to share their ideas, information or opinion. It is based on low self-efficacy about one’s capabilities, and ethical leadership enhance self-efficacy (Walumbwa & Schaubroeck, 2009). The employee could see their capacious side, which could eventually reduce the acquiescent silence.

Defensive silence is withholding relevant ideas, information or opinions as a form of self-protection based on fear. It is considered an agile strategy to keep information hidden from others. Although a person can speak up, he/she analyzes the cost and benefit of information sharing and then for self-protection, he/she remains silent (Milliken et al., 2003). Defensive silence is based on fear. The emotion of fear causes a negative behavioural response. To overcome this emotion, defensive silence is used by employees. And leadership styles like authoritative leadership increase defensive silence (Guo et al., 2018). But ethical leadership style, according to its definition, shows morality as a fundamental part.

The third type of silence is prosocial silence. Prosocial silence is referred to as the withholding of related ideas, information, or opinions to benefit other people or the organization based on altruism or cooperative motives. This type of silence occurs because of the concern for other employees, so the employees remain silent for benefiting his/her colleagues and do not share important information or opinion (Podsakoff, 2000). Project team members’ silence is driven by these inspirations that influence the successful completion (Ekrot et al., 2016). Prosocial silence occurs due to the concern for colleagues and the community (Brinsfield, 2013). It is concerned with the safety of coworkers (Morrison, 2014). It depends on interpersonal relations because it is derived from safety, which could create a problem for project managers (Zhu et al., 2019). According to previous studies, ethical leadership is related to prosocial attitude (Avey et al., 2011). In light of all this literature background, it is proposed here:

H1 Ethical leadership is negatively related to Project Team Members’ Silence (a. Acquiescent; b. Defensive; c. Prosocial).

Mediating Role of Subordinates Feeling Trusted and Loyalty

A crucial part of a working relationship is trust between two parties, and this topic has been gaining very much attention from researchers (De Jong et al., 2016). Feeling trusted is described as the perception of the trusted other of whether he or she is trusted by others (Lau et al., 2007). Feeling trusted reflects one's awareness of trustee disclosed weakness and inspirational desires, which indicates that trusted groups are loyal, trustworthy and proficient (Lau et al., 2014). Trusting and feeling trusted are two different constructs, even though they are regularly referenced together (Brower et al., 2000). But in this study, we centre around the impact of a leader on subordinates' view of being trusted because leaders' impact is fundamental inside vertical dyads.

Both feelings trusted, and trust applies extensive impacts on relational cooperation and further determine work viability (Brower et al., 2009). Trusting interaction between leaders and subordinates is more complex than colleagues' trust because leaders and subordinates have unequal positions in an organization. In prior research, some studies suggested that when leaders trust their subordinates, they generally conduct particular action toward trustworthy subordinates to enable them to attempt significant tasks (Gómez & Rosen, 2001; Ladegard & Gjerde, 2014). Many researchers, who investigated the pros and cons of subordinate feeling trusted by the leader, demonstrated that subordinates feel that their leader trusts them. This may have expanded their self-esteem, trust and company based confidence, which at last adds more to the significant levels of execution. Lau & Liden (2008) found that when a supervisor or leader trusts an employee, other workers also do likewise, mainly when the climate is questionable and uncertain. Trusting in employees at this point does not seem to be misused, and they experience more conviction at work since they can anticipate that their leader should act in skilful, unsurprising, and supportive ways (Colquitt et al., 2012; van den Bos & Lind, 2002).

This study uses social exchange theory to clarify the hypothetical connection between these two variables, ethical leadership and subordinates feeling trusted. This theory proposes that positive and beneficial activities coordinated to the subordinates by their supervisors lead to the improvement of great exchange connections that produce commitments for subordinates to respond in similarly specific manners (Zagenczyk et al., 2020). Leaders who adopt ethical leadership are philanthropic (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). They genuinely care about the prosperity of their subordinates, urge them to voice their interests and settle on reasonable and adjusted choices about issues that are essential to them (Brown et al., 2005). Furthermore, ethical leaders try to do as they say others should do (Brown et al., 2005). Such certain practices concerning managers make commitments for the subordinates to respond, which they do by demonstrating more important trust in their leader (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002).

According to the study of Lau (Lau et al., 2007), the feeling of being trusted increases as a type of mental strength, which can be perceived as the combination of recognition, equality, leader’s help and information sharing. Employees could feel more confident and trusted when their leader hand them over high profile projects and more important tasks and take their suggestions in decision making. According to Lau (Lau et al., 2014), when subordinates feel that their leader trusts them, it enhances their self-efficacy. In this manner, project team members feel pleased with their work by being feeling trusted. Various types of cohesions in qualities and inclinations support the sense of being trusted (Lau et al., 2007). Simultaneously, project team members' view of feeling trusted is connected positively with their leaders' ethical initiative practices, for example, being unselfish, equitable and reasonable for all (Hannah et al., 2005). By psychological impact, trust has a positive influence on the accomplishment of completed projects (Buvik & Rolfsen, 2015). It is believed that project team members are allowed to deal with the interdependencies between their different skills sets in activities (Chiocchio et al., 2011) by participating in information and data sharing. According to prior research, it is investigated that subordinates feeling trusted significantly impact leader-member relation (Skiba & Wildman, 2019).

This study investigates the part of subordinates feeling trusted and arranges the conversation inside project based settings. Extant literature inscribed to the harmony between trust and control in projects (Kalkman & de Waard, 2017). In any case, silence is not dependent upon primary control since cross-examination is not attainable. However, silence can be broken with mental change by guiding trust. That is why mediation of subordinate feeling trusted in the relationship of ethical leadership and project team members’ silence is studied. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H2 Subordinate Feeling Trusted mediates the relationship of Ethical Leadership and Project Team Members’ Silence (a. Acquiescent; b. Defensive; c. Prosocial).

Loyalty is defined as the relative strength of a subordinate’s identification with, attachment and dedication to a particular supervisor (Farh et al., 1998). The salient role of the supervisor is studied before (Farh & Cheng, 2000), which stated that people who possess inferior job are bound to be dutiful and loyal to their particular bosses. Then again, people involved in the better jobs are assumed to be generous and kind toward the employees with lower management. Loyalty as an idea has been an object important for researchers in various examination fields, bringing about different illustrations of its central highlights. From a hierarchical point of view, loyalty can be characterized as the rule of prejudice toward an item that increases desires for conduct in the interest of that item, for example, dependability and favorable to sociality (Hildreth et al., 2016). According to this point of view, it is consequently expected that the idea of loyalty depicts a relationship in which an individual considers. He/she is doing the morally right thing by putting together his/her conduct on the supposition that it would be the most significant advantage for the leader to which he/she is faithful.

Past investigations have affirmed that ethical leaders are pivotal for practising ethical practices among workers (Kalshoven et al., 2011). Loyalty is a significant component of ethics in the working environment (Sarwar et al., 2020). In addition, as per social learning theory, workers will learn qualities, perspectives and habits from their leaders (Pahl-Wostl & Hare, 2004). Al-Rafee & Cronan (2006) argued that learning from others (for example, colleagues and leaders) would significantly build up an individual's point of view toward an unethical activity. Therefore, the loyalty of workers may increase towards their organization by acknowledging through their leaders’ behaviour. Suppose the leaders and organizations work fairly, ethically and loyally. In that case, the workers will treat them in the same manner, and they would be more motivated to work for the organisation's benefit.

In literature, it is explained that leadership support can increase employee loyalty (Farrukh et al., 2019). The previous studies discovered that ethical leadership was positively associated with workers' intellectual ability and loyalty to the organization and uncovered that ethical leadership could have foreseen employees' loyalty to the organization. According to Wang, et al., (2017), it is investigated that ethical leadership increases loyalty of employees towards their managers. According to these arguments, the relation of loyalty towards supervisor with ethical leadership and employees’ silence is studied, but loyalty is not studied as a mediator between ethical leadership and silence of project team members. To fill this gap, it is proposed in this study:

H3 Loyalty mediates the relationship of Ethical Leadership and Project Team Members’ Silence (a. Acquiescent; b. Defensive; c. Prosocial).

The loyalty of employee towards his/her supervisor could also be seen in the setting of the condition with respect to correspondence between the worker and the supervisor (Alikhanova et al., 2020). In this extensive background, there is shared acknowledgement between representatives and supervisors on the functions of the organization. It is seen that organizations expecting elevated levels of faithfulness from their representatives should similarly respond to the loyalty shown by their workers. As per leader-member exchange theory, the great leader-member exchange relation is portrayed by trust and loyalty (Sherony & Green, 2002). Liden, et al., (1997) expressed that the connection among managers and subordinates builds as the business-related ex-change occurs. Inside team individuals, the leader-member exchange relation is frequently described as high calibre, for example, trust, regard, and loyalty. Loyalty happens when a decent leader-member exchange relation is responded to with trust practices among leader and subordinate. These exchanges create a sense of commitment in subordinates to respond and elevate standards of response (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

Individuals can respond each other's courtesies in relational collaboration (Malhotra & Murnighan, 2002). When feeling trusted, subordinates may respond in association with their leader. There are two impacts for which subordinates' view of being trusted holds basic noteworthiness in the trust-loyalty collaboration among bosses and subordinates. One is expanding subordinates' fulfillment with the leader, and the other is expanding subordinate reliability to the administrator. The sense of being trusted is connected positively with one's confidence just as results notwithstanding the loyalty to the project manager (Brown et al., 2005).

Subordinates will create loyalty towards leader in correspondence of being trusted. From the subordinate’s viewpoint, when the subordinates feel trusted, this probably will be the beneficiaries for more advantages and will be expanding confidence (Pierce & Gardner, 2004). Thus, subordinates ought to be aroused to perform well and be more faithful in interchange relationships (Brower et al., 2000). In previous research, it is discovered that if the time horizon of a loyal employee increases in an organization, his/her silence will decrease. It means that loyalty will decrease the silence of employees, and reduction of employee silence is significant, as according to literature, communication in projects is a critical factor of sustainable project management, especially in construction projects (Kiani Mavi & Standing, 2018). It is a very crucial relationship, which did not get much attention, so to fill this gap, it is hypothesized that:

H4 Subordinate Feeling trusted and Loyalty sequentially mediates the relationship of Ethical Leadership and Project Team Members’ Silence (a. Acquiescent; b. Defensive; c. Prosocial).

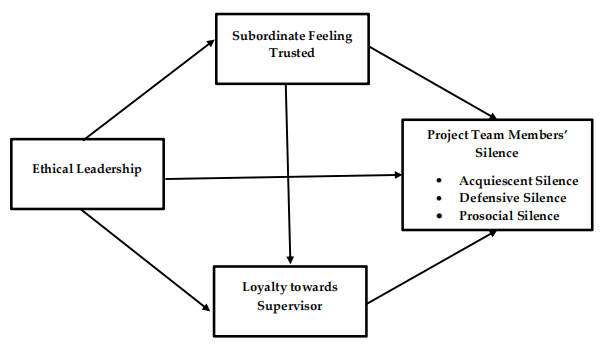

This study examines the effect of ethical leadership on project team members’ silence through the mediation of subordinate feeling trusted and loyalty towards the supervisor. Figure 1 presented the conceptual model of the study.

Material and Methods

This study aims to test the impact of ethical leadership on the silence of project team members through feeling trusted and loyalty. The study participants belonged to the construction sector of Pakistan. The construction industry is considered the backbone of the economy around the world. It contributes 2.3% to 2.85% to the GDP of Pakistan (Adil, 2020). But, still, it faces many challenges due to its dynamic nature of business, where diversified tasks are performed during the project. Different teams are involved during the project life cycle that can often create conflicts among the team members, ultimately resulting in poor project performance (Rahman & Kumaraswamy, 2004). That is why it needs to apply more project management practices for getting successful results.

The convenience sampling technique was used to collect data from the team members involved in the projects. The researchers had taken prior permission from the management of the construction companies before contacting the targeted participants. The participants were also informed about the research objectives, and their prior consent was also taken before starting the survey. 470 questionnaires were distributed to the respondents through emails and personal visits. Out of 470 questionnaires, 377 were received back; 43 responses had missing values and outliers. So, those responses were deleted. The remaining 334 responses were used with a response rate of 71.06%. Table 1 shows a brief summary of demographics features of respondents.

| Table 1 Demographic Features |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Distribution | Frequency | Percentage |

| Gender | Male | 311 | 93.1% |

| Female | 23 | 6.9% | |

| Age | 18-28 | 83 | 24.9% |

| 29-39 | 202 | 60.5% | |

| 40 or above | 49 | 14.7% | |

| Job Level | Top Management | 2 | 0.6% |

| Middle Management | 22 | 6.6% | |

| Lower Management | 310 | 92.8% | |

| Experience | 5 or less | 205 | 61.4% |

| 6-10 | 119 | 35.6% | |

| 11 or above | 10 | 3% | |

| Qualification | Inter | 28 | 8.4% |

| Bachelor | 214 | 64.1% | |

| Masters | 84 | 25.1% | |

| PhD | 8 | 2.4% | |

Table 1 shows that out of 334 respondents, 93.1% were male, and 6.9% were female. So mostly male re-spondents participated in this study. Three age groups were added, and mostly (61%) participants’ age was be-tween 29 to 39. Almost 93% of respondents from lower management who were engaged directly in projects participated in this study. The experience of the respondents was added in years. Three groups of experience were added so the respondents could easily pick one of their choices. Most of them (61%) had 5 years or less than 5 years of working experience. The qualification of respondents was inter to Ph.D and mostly (64%) had bachelor degrees. These results showed that the qualification of respondents was Inter or above, so they were able to understand the questions easily.

Measures

Project team member silence refers to a situation where team members intentionally concealed any project related information from the management, coworkers, and experts useful in decision-making (Pinder & Harlos, 2001). Van Dyne, et al., (2003) used three dimensions of silence (acquiescent; defensive; prosocial), measured with 13 items. Ethical leadership demonstrates normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships and promotes such conduct to subordinates through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (Piccolo et al., 2010). It was measured by using ten items introduced by (Brown et al., 2005). Subordinates feeling trusted are defined as subordinates' perception of being trusted by their supervisors and others team members (Zhu et al., 2019), assessed by four items developed by Lau et al. (Lau et al., 2007). Loyalty to a supervisor is the relative strength of a subordinate’s identification with, attachment and dedication to a particular supervisor (Wang et al., 2017), evaluated by 17 items introduced by Chen et al. (Farh et al., 1998). All the questionnaire items were quantified on Five-point Likert Scale (1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree).

Results

This section provides a summarized description of the empirical results. It discusses their interpretation, as well as the conclusions, are drawn from it. First, the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs is checked. Table 2 explains the measurement model using internal consistency and convergent validity of data. Convergent validity measures constructs that should be correlated with one another discovered to be associated with one another. Outer loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is used to check the convergent validity of indicators. The values of outer loadings are greater than 0.70 is which acceptable (Khan et al., 2020). The AVE calculates the convergent validity of each construct. Its minimum threshold value is 0.50. Internal consistency is measured with Cronbach’s Alpha with the minimum threshold value of 0.70. Table 2 confirms the internal consistency and convergent validity of the data.

| Table 2 Construct Reliability and Validity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | Cronbach's Alpha | AVE |

| Ethical Leadership | EL1 | 0.707 | 0.889 | 0.501 |

| EL2 | 0.707 | |||

| EL3 | 0.708 | |||

| EL4 | 0.715 | |||

| EL5 | 0.704 | |||

| EL6 | 0.703 | |||

| EL7 | 0.711 | |||

| EL8 | 0.705 | |||

| EL9 | 0.708 | |||

| EL10 | 0.708 | |||

| Project Team Members' Silence | AS1 | 0.738 | 0.727 | 0.547 |

| AS2 | 0.707 | |||

| AS3 | 0.705 | |||

| AS4 | 0.804 | |||

| DS1 | 0.721 | 0.788 | 0.540 | |

| DS2 | 0.743 | |||

| DS3 | 0.749 | |||

| DS4 | 0.729 | |||

| DS5 | 0.733 | |||

| PS1 | 0.715 | 0.785 | 0.609 | |

| PS2 | 0.804 | |||

| PS3 | 0.823 | |||

| PS4 | 0.776 | |||

| Subordinates Feeling Trusted | SFT1 | 0.721 | 0.761 | 0.582 |

| SFT2 | 0.720 | |||

| SFT3 | 0.788 | |||

| SFT4 | 0.819 | |||

| Loyalty Towards Supervisor | LTS1 | 0.705 | 0.938 | 0.502 |

| LTS2 | 0.710 | |||

| LTS3 | 0.712 | |||

| LTS4 | 0.713 | |||

| LTS5 | 0.711 | |||

| LTS6 | 0.709 | |||

| LTS7 | 0.718 | |||

| LTS8 | 0.707 | |||

| LTS9 | 0.702 | |||

| LTS10 | 0.717 | |||

| LTS11 | 0.706 | |||

| LTS12 | 0.702 | |||

| LTS13 | 0.700 | |||

| LTS14 | 0.715 | |||

| LTS15 | 0.707 | |||

| LTS16 | 0.713 | |||

| LTS17 | 0.700 | |||

Discriminant validity illustrates that the indicators of a construct differ from indicators of other constructs in a path model, where the values of constructs’ cross-loading are always greater than other constructs (Iqbal Khan et al., 2020). Discriminant validity was checked by using Fornell & Larcker Criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The Discriminant validity through Fornell & Larcker Criterion tells that the square root of the construct’s AVE is compared with the correlations of other constructs, and it should be greater than the correlations of other con-structs. Table 3 satisfies the requirement of discriminant validity because all the values of the square root of AVE were greater than other constructs.

| Table 3 Discriminant Validity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | EL | LTS | AS | DS | PS | SFT |

| EL | 0.708 | |||||

| LTS | 0.652 | 0.709 | ||||

| AS | -0.485 | -0.565 | 0.739 | |||

| DS | -0.487 | -0.508 | 0.671 | 0.735 | ||

| PS | -0.424 | -0.457 | 0.616 | 0.599 | 0.781 | |

| SFT | 0.582 | 0.525 | -0.458 | -0.512 | -0.395 | 0.763 |

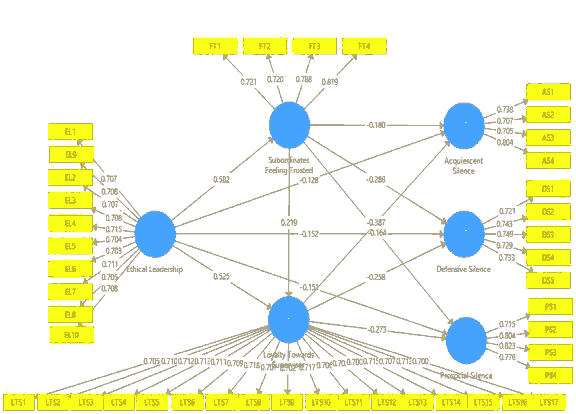

The structural model was accessed using R2, β value, t-value and p-value of hypotheses to know whether the hypotheses are accepted or rejected. The coefficient of determination measures the overall effect size and variance explained in the endogenous construct for the structural model. In figure 2, the values of R Square for loyalty towards the supervisor, acquiescent silence, defensive silence, prosocial silence and subordinates feeling trusted were 0.457, 0.363, 0.352, 0.253 and 0.339, respectively, which means that ethical leadership brought 45.7% change in loyalty towards supervisor, 36.3% change in acquiescent silence, 35.2% effect on defensive silence, 25.3% variation in prosocial silence and 33.9% change in subordinates feeling trusted.

Model fit is also checked by using Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Chi-Square, Normed Fit Index (NFI). SRMR is accessed to determine the difference between observed correlation, and the model implied correlation matrix and the value less than 0.10 or 0.08 is considered a good fit for the model. Here the value of SRMR is 0.071. Chi-square is used to compare the actual model with the expected model. The value of chi-square is 3363.53. NFI is derived from chi-square by subtracting the value of chi-square of the proposed model from 1 and divided the value by the chi-square value of the null model (Table 4). It ranges from 0 to 1. The closer the value of NFI to 1, the better it is for the model. For this model, the value of NFI is 0.637. It shows that the observed model is a good fit.

| Table 4 Direct and Indirect Effect |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | β-value | t-value | p-value |

| i. Direct Effects | |||

| EL -> AS | -0.128 | 2.076 | 0.038 |

| EL -> DS | -0.152 | 2.333 | 0.020 |

| EL -> PS | -0.151 | 2.099 | 0.036 |

| EL -> SFT | 0.582 | 12.239 | 0.000 |

| LTS -> AS | -0.387 | 6.469 | 0.000 |

| LTS -> DS | -0.258 | 4.904 | 0.000 |

| LTS -> PS | -0.273 | 4.287 | 0.000 |

| SFT -> LTS | 0.219 | 4.051 | 0.000 |

| SFT -> AS | -0.180 | 3.284 | 0.001 |

| SFT -> DS | -0.288 | 5.207 | 0.000 |

| SFT -> PS | -0.164 | 2.690 | 0.007 |

| ii. Indirect Effects | |||

| EL -> SFT -> AS | -0.105 | 3.048 | 0.002 |

| EL -> SFT -> DS | -0.168 | 5.037 | 0.000 |

| EL -> SFT -> PS | -0.096 | 2.494 | 0.013 |

| EL -> LTS -> AS | -0.203 | 5.172 | 0.000 |

| EL -> LTS -> DS | -0.135 | 3.822 | 0.000 |

| EL -> LTS -> PS | -0.143 | 2.710 | 0.007 |

| EL -> SFT -> LTS -> AS | -0.049 | 2.999 | 0.003 |

| EL -> SFT -> LTS -> DS | -0.033 | 3.022 | 0.003 |

| EL -> SFT -> LTS -> PS | -0.035 | 2.566 | 0.011 |

The β value denoted the expected variation in the dependent construct for a unit variation in the independent construct(s). The β values of every path in the hypothesized model were computed; the greater the β value, the more the substantial effect on the endogenous latent constructs. However, the β value had to be verified for its significance level through the t-statistics test. The bootstrapping procedure was used to evaluate the significance of the hypothesis. In H1a, we anticipated that ethical leadership is negatively related to project team members’ acquiescent silence and results showed that this hypothesis was strongly supported (β=-0.128, t-value=2.076 and p-value<0.038).

Same as H1a, we hypothesized for H1b and H1c that ethical leadership negatively related to defensive silence (β=-0.152, t-value=2.333 and p-value<0.020) and prosocial silence (β=-0.151, t-value=2.099 and p-value<0.036) respectively and these both hypotheses were accepted. In H2a, H2b and H2c we predicted that subordinates feeling trusted would mediate the relationship of ethical leadership and project team members’ silence (a:acquiescent silence, b:defensive silence and c:prosocial silence). These hypotheses were robustly supported with the results (β=-0.105, t-value=3.048 and p-value<0.002), (β=-0.168, t-value=5.037 and p-value<0.000) and (β=-0.096, t-value=2.494 and p-value<0.013).

Furthermore, we projected about H3a, H3b and H3c that loyalty would have mediation between ethical leadership and project team members’ silence (a:acquiescent silence, b:defensive silence and c:prosocial silence). And we observed through results (β=-0.203, t-value=5.172 and p-value<0.000), (β=-0.135, t-value=3.822 and p-value<0.000) and (β=-0.143, t-value=2.710 and p-value<0.007) that these hypotheses are supported. Likewise, H4a H4b and H4c were about sequential mediation of subordinates feeling trusted and loyalty in the relationship of ethical leadership and project team members’ acquiescent, defensive and prosocial silence. The results showed (β=-0.049, t-value=2.999 and p-value<0.003), (β=-0.033, t-value=3.022 and p-value<0.003) and (β=-0.035, t-value=2.566 and p-value<0.011) the partial mediation of both mediators.

Discussion

The root cause of conducting this research was to find out whether ethical leadership could reduce the silence of project team members or not. First of all, the effect of ethical leadership on project team members’ silence was observed. As discussed before, there were three dimensions of silence that had been studied previously. The results confirmed that ethical leadership significantly impacted all three types of silence: acquiescent silence, defensive silence, and prosocial silence. Ethical leadership had a negative effect on these three types, which means that ethical leadership can reduce the project team members’ silence. This study filled the gap of the previous study by affecting acquiescent silence (Zhu et al., 2019). This study remained consistent with previous studies, which showed that ethical leadership could enhance self-efficacy (Naeem et al., 2020). So, the H1a, H1b and H1c were accepted.

Second hypothesis H2 was about the mediation of subordinates feeling trusted. The results proved that ethical leadership was positively related to subordinates' feeling trusted, which means that because of ethical leadership, subordinates feel that they are being trusted, which motivates them to perform challenging tasks. The relationship of subordinates feeling trusted and project team members silence was significant but negative, consistent with prior studies (Dedahanov et al., 2016). Therefore, this study suggested the mediation of subordinates feeling trusted in the relationship of ethical leadership and project team members’ silence (acquiescent, defensive and prosocial), but it partially mediated the direct relationship. These results indicated that ethical leadership could reduce the silence of team members by building a strong relationship of trust with the subordinates. The subordinates might want to fulfil the need to be trusted by the leader to reduce their silence and speak about anything they think is right. It will encourage them to be motivated; however they have to face difficulties.

H3 was also supported as it showed the mediation of loyalty towards supervisor in the relationship of ethical leadership and project team members’ silence. Ethical leadership directly relates to loyalty towards the supervisor, which was accordant with the previous study, which said that ethical leadership could increase employee commitment (Wang et al., 2017). Loyalty towards supervisor can reduce project team members’ silence (acquiescent, defensive and prosocial). Therefore, the indirect relation exhibited that the mediation of loyalty towards the supervisor can increase ethical leadership's effect on project team members’ silence. However, the mediation was partial as the direct and indirect effects were significant simultaneously.

H4 indicated the sequential mediation, first the mediation of subordinates feeling trusted and then the mediation of loyalty. It showed that ethical leadership was related to subordinates feeling trusted and loyal towards the supervisor, which reduced the silence (acquiescent, defensive and prosocial) of project team members. If the silence of project team members reduced and they changed their behaviour, it would strengthen the iron triangle (time, budget and quality) of project management (Gilbert Silvius et al., 2017). The results showed that sequential mediation had increased the impact of both mediators on a direct relationship. So here are these constructs which can help to break the silent behaviour of team members who would be working on any project. According to the literature, an ethical leadership style can build a strong social exchange relationship with subordinates, which would lead the organization towards success (Hansen, 2011). It also supported leader-member exchange theory by increasing trust and loyalty related to ethical leadership. This study reinforced the previous studies, extended the literature related to these constructs, and provided a deep understanding of these constructs.

Practical and Theoretical Implications

As the silent behaviour of employees is considered hazardous for communication, the interruption in this conduct of employees is very important. Since there is no prior study on the relationship of ethical leadership and project team members’ silence, especially in Pakistan, this study is theoretically as well as practically beneficial for project-based organizations or for those working on projects (long term or short term). This may be the first study that explored the effect of ethical leadership on the silence of team member, specifically in the context of the project, through the mediation of subordinates feeling trusted and loyalty towards the supervisor. It is equally fruitful for project managers in many ways. Theoretically, this study contributed to project management literature by explaining the relationship between ethical leadership and project team members’ silence. Subordinates feeling trusted and loyalty towards the supervisor are acknowledged as mediators in the relationship between ethical leadership and project team members’ silence. This study has reinforced the idea about leadership and silent behaviour. Understanding the impact of leadership on the project settings is also enhanced further (Müller & Turner, 2007).

This study also has some practical implications. Most of the construction projects fail due to unethical professionals practices (Usman et al., 2012). Therefore, project managers should adopt an ethical leadership style. It will break the silent behavior of team members and help the team members feel trusted, further reducing their turnover rate, counterproductive behaviour, and work stress. Because of this conduct, their loyalty will increase, which will eventually help to minimize the silent behaviour to some more extent. Therefore, the project managers need to express their trust towards their subordinates to gain there, and it will encourage them to share the information with their supervisors or leaders. With the reduction of silence behaviour, communication during the execution of projects will be constant, which will lead to the success of the project. Reduction in project failure will encourage initiating more projects in Pakistan.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence on the relationship of ethical leadership and silence of project team members through mediating role of subordinates feeling trusted and loyalty. It suggests that ethical leadership is an essential construct for breaking employees' silent behaviour, especially in construction projects where leaders' moral code of conduct is inevitable for employee loyalty and continual communication. The study findings are supported by social exchange relationship, and leader-member exchange theory which builds the relationship of ethical leadership emphasizes the employee to share information in exchange for ethical behaviour of the leader. The results indicate that ethical leadership has a negative and significant impact on project team members’ silence (acquiescent, defensive and prosocial). Subordinates feeling trusted and loyalty mediate this relationship and shows that these constructs partially mediates the direct relationship. Both mediators specify that ethical leadership would be more promising to reduce silent behaviour through sequential mediation.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are some limitations of this study that guide future researches to fill these gaps. First of all, this study is conducted from the perspective of subordinates, but employer or leader is also involved, so the future re-searcher can investigate this issue using a later perspective. This study is conducted with only one leadership style; maybe other leadership styles could also be helpful for this kind of situations so future researchers can examine the effect of other leadership styles, e.g. charismatic leadership style or Laissez faire leadership style etc. It will strengthen the literature about the silence of team members of projects. Another limitation is associated with sample size. Data collection was collected simultaneously with the same questionnaire, so there could be chances of error of systematic measurement. It was impossible to collect data from the whole population due to the shortage of time, so a small sample size was selected for data collection. It is not an effective way to collect data for an important issue. Due to the short sample size, it is challenging to generalize these results. This study was quantitative, which may neglect many other perspectives of silence behaviour, so a qualitative study, e.g. case study, should be conducted for more in-depth results and understanding of the silencing behaviour related to project management.

Data were collected only from one city of Pakistan, Lahore, so it is difficult to generalize these results to the whole country. The difference in culture could be a reason for the alteration of results. This could lead to a greater insight into the issue in diversified manners. So, these constructs should be studied in other and different cultures. Only two constructs feeling trusted and loyalty was found to consider mediation, but it can also be investigated with other contextual constructs, for example, trust in supervisor, self-efficacy and employee engagement etc. Silent behaviour of employees increases the stress of employees, which can be deal with ethical leadership. There could be more psychological impacts of silence on employees, but this study only identifies stress, so there is a need to identify more psychological factors related to silence. Communication is one of the critical factors that affect the success of the organization. The continuous halts that occur in communication at the workplace increase the psychological issues among the employees (Morsch & Kodden, 2020). That not only affect their mental health but also affect their project performance. This study suggests the future researchers extend our conceptual model and investigate the negative consequences of employees silence on the psychological health.

References

- Adil, M.M. (2020). Will the construction industry revive Pakistan’s economy?

- Al-Rafee, S., & Cronan, T.P. (2006). Digital piracy: Factors that influence attitude toward behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(3), 237–259.

- Alikhanova, L.H., Mineva, O.K., & Smirnova, D.S. (2020). Employee online surveys: Satisfaction, engagement, loyalty, and readiness for personal branding. Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics, Management and Technologies 2020 (ICEMT 2020), 553–559.

- Avey, J.B., Reichard, R.J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K.H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127–152.

- Banihashemi, S., Hosseini, M.R., Golizadeh, H., & Sankaran, S. (2017). Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for integration of sustainability into construction project management practices in developing countries. International Journal of Project Management, 35(6), 1103–1119.

- Brinsfield, C.T. (2013). Employee silence motives: Investigation of dimensionality and development of measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(5), 671–697.

- Brinsfield, C.T., & Edwards, M.S. (2020). Handbook of research on employee voice. 103–120. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Brower, H.H., Lester, S.W., Korsgaard, A.M., & Dineen, B.R. (2009). A closer look at trust between managers and subor-dinates: Understanding the effects of both trusting and being trusted on subordinate outcomes. Journal of Management, 35(2), 327–347.

- Brower, H.H., Schoorman, F.D., & Tan, H.H. (2000). A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and lead-er-member exchange. Leadership Quarterly, 11(2), 227–250.

- Brown, M.E., Treviño, L.K., & Harrison, D.A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct de-velopment and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

- Bubshait, A.A., Siddiqui, M.K., & Al-Buali, A.M.A. (2015). Role of communication and coordination in project success: Case study. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 29(4), 1–7.

- Buvik, M.P., & Rolfsen, M. (2015). Prior ties and trust development in project teams - A case study from the construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 33(7), 1484–1494.

- Chiocchio, F., Forgues, D., Paradis, D., & Iordanova, I. (2011). Teamwork in integrated design projects: Understanding the effects of trust, conflict, and collaboration on performance. Project Management Journal, 42(6), 78–91.

- Colquitt, J.A., LePine, J.A., Piccolo, R.F., Zapata, C.P., & Rich, B.L. (2012). Explaining the justice-performance rela-tionship: Trust as exchange deepener or trust as uncertainty reducer? Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 1–15.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

- De Jong, B.A., Dirks, K.T., & Gillespie, N. (2016). Trust and team performance: A meta-analysis of main effects, moderators, and covariates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(8), 1134–1150.

- Dedahanov, A.T., Lee, D.H., Rhee, J., & Yoon, J. (2016). Entrepreneur’s paternalistic leadership style and creativity: The mediating role of employee voice. Management Decision, 54(9), 2310–2324.

- Demirkesen, S., & Ozorhon, B. (2017). Measuring project management performance: Case of construction industry. EMJ-Engineering Management Journal, 29(4), 258–277.

- Detert, J.R., & Burris, E.R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Man-agement Journal, 50(4), 869–884.

- Detert, J.R., & Edmondson, A.C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 461–488.

- Dirks, K.T., & Ferrin, D.L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628.

- Ekrot, B., Rank, J., & Gemünden, H.G. (2016). Antecedents of project managers’ voice behavior: The moderating effect of organization-based self-esteem and affective organizational commitment. International Journal of Project Management, 34(6), 1028–1042.

- Farh, J.L., & Cheng, B.S. (2000). A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In Management and Organizations in the Chinese Context, 84–127. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Farh, L.J.L., Chen, Z., & Tsui, A.S. (1998). Loyalty to supervisor, organizational commitment, and employee outcomes : The Chinese case. Annual National Meeting of Academy of Management.

- Farrukh, M., Kalimuthu, R., & Farrukh, S. (2019). Impact of job satisfaction and mutual trust on employee loyalty in saudi hospitality industry: A mediating analysis of leader support. International Journal of Business and Psychology, 1(2), 30–52.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Al-gebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

- Gilbert Silvius, A.J., Kampinga, M., Paniagua, S., & Mooi, H. (2017). Considering sustainability in project management decision making: An investigation using Q-methodology. International Journal of Project Management, 35(6), 1133–1150.

- Gómez, C., & Rosen, B. (2001). The leader-member exchange as a link between managerial trust and employee em-powerment. Group and Organization Management, 26(1), 53–69.

- Guo, L., Decoster, S., Babalola, M.T., De Schutter, L., Garba, O.A., & Riisla, K. (2018). Authoritarian leadership and em-ployee creativity: The moderating role of psychological capital and the mediating role of fear and defensive silence. Journal of Business Research, 92, 219–230.

- Hannah, S.T., Lester, P.B., & Vogelgesang, G.R. (2005). Moral leadership: Explicating the moral component of authentic leadership. Authentic leadership theory and practice. Origins, Effects, and Development Monographs in Leadership and Management, 3, 43–81.

- Hansen, D.S. (2011). Ethical leadership: A multifoci social exchange perspective. Journal of Business Inquiry, 10(425), 41–55.

- Hildreth, J.A.D., Gino, F., & Bazerman, M. (2016). Blind loyalty? When group loyalty makes us see evil or engage in it. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 132, 16–36.

- Iqbal Khan, K., Ali, M., Mahmood, S., & Raza, A. (2020). Power of brand awareness in generating loyalty among youth through reputation, customer engagement and trust. International Journal of Management Research and Emerging Sciences, 10(1), 98–110.

- Joshi, A., & Roh, H. (2009). The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review. Academy of Management Journal, 52(3), 599–627.

- Kalkman, J.P., & de Waard, E.J. (2017). Inter-organizational disaster management projects: Finding the middle way between trust and control. International Journal of Project Management, 35(5), 889–899.

- Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D.N., & De Hoogh, A.H.B. (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Devel-opment and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 51–69.

- Khan, K.I., Naqvi, S.M.W.A., Ghafoor, M.M., & Nayab, G. (2020). Effect of reward system on innovative work behaviour through temporary organizational commitment and proficiency: Moderating role of ulticulturalism. International Journal of Management Research and Emerging Sciences, 10(2), 96–108.

- Kiani, M.R., & Standing, C. (2018). Critical success factors of sustainable project management in construction: A fuzzy DEMATEL-ANP approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 194, 751–765.

- Kliem, R. (2004). Managing the risks of offshore it development projects. The EDP Audit, Control, and Security Newsletter, 32(4), 12–20.

- Ladegard, G., & Gjerde, S. (2014). Leadership coaching, leader role-efficacy, and trust in subordinates. A mixed methods study assessing leadership coaching as a leadership development tool. Leadership Quarterly, 25(4), 631–646.

- Lau, D.C., Lam, L.W., & Wen, S.S. (2014). Examining the effects of feeling trusted by supervisors in the workplace: A self-evaluative perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 112–127.

- Lau, D.C., & Liden, R.C. (2008). Antecedents of coworker trust: Leaders’ blessings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1130–1138.

- Lau, D.C., Liu, J., & Fu, P.P. (2007). Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: Antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(3), 321–340.

- Liden, R.C., Sparrowe, R.T., & Wayne, S.J. (1997). Leader-member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management, 15, 47–119.

- Mahmood, S., Qadeer, F., Sheeraz, M., & Khan, K. (2017). Line managers’ HR implementation level and work performance: Estimating the mediating role of employee outcomes. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 11(3), 959–976.

- Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J.K. (2002). The effects of contracts on interpersonal trust. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(3), 534–559.

- Milliken, F.J., Morrison, E.W., & Hewlin, P.F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476.

- Morrison, E.W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organiza-tional Behavior, 1(1), 173–197.

- Morrison, E.W., & Milliken, F.J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a plu-ralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725.

- Morsch, J., & Kodden, B. (2020). The impact of perceived psychological contract breach, abusive supervision, and silence on employee well-being. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 22(2).

- Müller, R., & Turner, J.R. (2007). Matching the project manager’s leadership style to project type. International Journal of Project Management, 25(1), 21–32.

- Naeem, R.M., Weng, Q., Hameed, Z., & Rasheed, M.I. (2020). Ethical leadership and work engagement: A moderated mediation model. Ethics and Behavior, 30(1), 63–82.

- Nechanska, E., Hughes, E., & Dundon, T. (2020). Towards an integration of employee voice and silence. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100674.

- Pahl-Wostl, C., & Hare, M. (2004). Processes of social learning in integrated resources management. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 14(3), 193–206.

- Piccolo, R.F., Greenbaum, R., den Hartog, D.N., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), 259–278.

- Pierce, J.L., & Gardner, D.G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organiza-tion-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591–622.

- Pinder, C.C., & Harlos, K.P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 20, 331–369.

- Podsakoff, P. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: a critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26(3), 513–563.

- Rahman, M.M., & Kumaraswamy, M.M. (2004). Contracting relationship trends and transitions. Journal of Management in Engineering, 20(4), 147–161.

- Sarwar, H., Ishaq, M.I., Amin, A., & Ahmed, R. (2020). Ethical leadership, work engagement, employees’ well-being, and performance: a cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2008–2026.

- Schwepker, C.H., & Dimitriou, C.K. (2021). Using ethical leadership to reduce job stress and improve performance quality in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102860.

- Sherony, K.M., & Green, S.G. (2002). Coworker exchange: Relationships between coworkers, leader-member exchange, and work attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 542–548.

- Skiba, T., & Wildman, J.L. (2019). Uncertainty reducer, exchange deepener, or self-determination enhancer? Feeling trust versus feeling trusted in supervisor-subordinate relationships. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 219–235.

- Toor, S.R., & Ofori, G. (2008). Leadership for future construction industry: Agenda for authentic leadership. International Journal of Project Management, 26(6), 620–630.

- Tyssen, A.K., Wald, A., & Heidenreich, S. (2014). Leadership in the context of temporary organizations: A study on the effects of transactional and transformational leadership on followers’ commitment in projects. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 21(4), 376–393.

- Usman, N.D., Inuwa, I.I., & Iro, A.I. (2012). The influence of unethical professional practices on the management of construction projects in north eastern states of Nigeria. International Journal of Economic Development Research and Investment, 3(2), 124–129.

- van den Bos, K., & Lind, E.A. (2002). Uncertainty management by means of fairness judgments. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 1–60.

- Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I.G. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392.

- Walumbwa, F.O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1275–1286.

- Wang, H., Lu, G., & Liu, Y. (2017). Ethical leadership and loyalty to supervisor in China: The roles of interactional justice and collectivistic orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(3), 529–543.

- Wu, G., Liu, C., Zhao, X., & Zuo, J. (2017). Investigating the relationship between communication-conflict interaction and project success among construction project teams. International Journal of Project Management, 35(8), 1466–1482.

- Zagenczyk, T.J., Purvis, R.L., Cruz, K.S., Thoroughgood, C.N., & Sawyer, K.B. (2020). Context and social exchange: perceived ethical climate strengthens the relationships between perceived organizational support and organizational identification and commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management.

- Zhu, F., Wang, L., Yu, M., Müller, R., & Sun, X. (2019). Transformational leadership and project team members’ silence: the mediating role of feeling trusted. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 12(4), 845–868.