Review Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Building the Eradication of Corruption in Indonesia Using Administrative Law

Muhammad Bagus Adi Wicaksono, Universitas Sebelas Maret

Rian Saputra, Faculty of Law, Universitas Slamet Riyadi

Keywords

Corruption, Abuse of Authority, Administrative Law

Abstract

This study aims to see and describe other alternatives in eradicating corruption due to abuse of power that is detrimental to state finances. This idea emerged after seeing that the paradigm of corruption eradication in Indonesia is currently still focused on punishment, thus forgetting one of the objectives of the Corruption Act, namely the return of state financial losses. This type of research is normative, with a statutory approach, conceptual approach, and case approach. The results of the study show that the eradication of corruption due to abuse of authority by government officials through the administrative law approach focuses more on returning state losses by: First, supervision of internal government agencies, in this case the Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus (APIP). APIP has the authority to carry out direct prosecution and ask for compensation. Second, with regard to external supervision, in the event that the Supervisory Agency (BPK) finds state financial losses, it would be good to take administrative action in an effort to recover state financial losses, by communicating with APIP for time efficiency in eradicating corruption and restoring state losses. Third, sanctions within the competent state that result in financial losses in Article 20 Juncto 21 of Law Number 30 of 2014 concerning governments that have not provided clear instrument sanctions in terms of abuse of authority that harm state finances by government officials and only provide administrative sanctions in the form of dismissal and there is no obligation to recover state financial losses.

Introduction

The administration of government in Indonesia is carried out by government officials in accordance with the authorities they have. The regulation regarding the authority is regulated in the form of laws that have clearly and clearly regulates the “governance management” both regarding “authority”, “authority”, “forms of government legal actions or actions”, “sanctions” and other related matters. with governance administration. In accordance with various societal developments, all matters relating to government management including legal actions in government administration also require good regulation regarding "authority", "types of legal action", "as well as the principles that form the basis of governance", namely "General Principles of Governance. good, the forms and types of supervision that need to be done" (Putriyanti, 2015). Law Number 30 of 2014 concerning Government Administration (hereinafter referred to as the AP Law), is a new regulation in the field of state administrative law regarding governance and is a new thing in the field of state administrative law which is the basis for management in decision making by administrative bodies and or officials. state effort. The management of government administration prior to the issuance of the AP Law is not only based on applicable laws and regulations but also based on existing norms, state administrative law principles. In practice, the norms and principles of state administrative law that are not written cause confusion in the administration of government (Putriyanti, 2015).

The increasing role of the government to take part (staatsbemoeienis) in many areas of community life in order to carry out public service duties (bestuurszorg) with the aim of improving the general welfare often results in Government Officials being faced with complex and urgent problems that force them to make decisions or actions that have not been regulated in statutory regulations as a form of situational power. Such situations usually cause Government Officials to be unable to refuse to do something on the grounds that "there are no governing rules" or on the grounds of "waiting for a new rule (rechtvacuum). Administrative areas that are gray areas can lead to criminal acts of corruption, this often happens where officials crash the rules that are considered gray areas but in fact mens rea/his intention is to enrich himself causing losses to the state (Saputra, 1988). What the author mentioned recently has often happened, it cannot even be denied that so far many government officials have been caught in criminal acts of corruption because of their decisions or actions. In the process of law enforcement, there are many elements of "against the law" and "abusing authority" which are accompanied by a statement that the amount of "state loss" is sufficient as a basis for accusing a government official with the threat of committing a criminal act of corruption (Ridwan, 2006).

This is as regulated in Article 3 of Law Number 31 Year 1999 jo. Law Number 20 of 2001 concerning Eradication of Corruption Crime (hereinafter referred to as the Corruption Act):

"Anyone who with the aim of benefiting himself or another person or a corporation, abuses his/her authority, opportunity or means because of his position or position which can harm the state finances or the state economy, shall be sentenced to life imprisonment or imprisonment of at least 1. (one) year and a maximum of 20 (twenty) years and or a fine of at least Rp. 50,000,000.00 (fifty million rupiah) and a maximum of Rp. 1,000,000,000.00 (one billion rupiah) ”.

Although, in its development, the article above is based on the Decision of the Constitutional Court Number 25/PUU-XIV/2016 that the word can be abolished so that there must be state losses first, so that there is a shift in article 3 of the Corruption Law from formal offense to material offense in order to guarantee legal certainty. However, as the author's explanation at the beginning after the birth of the AP Law, to be precise in Article 21 of the law, where to prove the existence of abuse of authority "Government agencies and/or officials can submit a request to the Court to assess whether or not there is an element of abuse of authority in decisions and/or Actions". The provisions in the AP Law ultimately lead to pros and cons among legal experts, especially Criminal Law experts and State Administrative Law experts regarding the validity of the provisions in question and their impact on the authority of the Corruption Court. Guntur Hamzah, "Professor of Administrative Law at Hasanuddin University, stated that the existence of the Government Administration Law will strengthen and increase the breaking force of efforts to eradicate corruption because with the existence of APIP, allegations of abuse of power can be detected early as a preventive effort". (hukumonlien.com)

However, a different opinion was conveyed by Krisna Harahap, "The Supreme Court Justice at the Supreme Court explicitly stated that the Government Administration Law hampers efforts to eradicate corruption because the provisions contained in the Government Administration Law are clearly not in line with the Corruption Eradication Law, especially Article 3". (newsdetik.com) Even worse, the provisions in the Government Administration Law can even reduce the authority of the Corruption Court in assessing the element of "abusing authority" in Corruption. "This is evident from President Jokowi's policy of instructing the Attorney General and the Chief of Police to prioritize government administration processes in accordance with the provisions of the Government Administration Law before conducting investigations into public reports regarding alleged abuse of power, particularly in the implementation of the National Strategic Project".

Regardless of the pros and cons of these experts, the author is of the view that this is not too surprising considering that in various parts of the world, “corruption always gets more attention than other criminal acts” (Vanuci, 2019). This phenomenon is understandable considering the negative impact caused by this crime. The impacts that are concluded can touch various areas of life. So that we recognize that corruption is a serious problem, this crime can endanger the stability and security of society, endanger socio-economic development, and also politics, and can destroy "democratic values" and "morality" because gradually this act seems to become a culture. . Corruption is a threat to the goal of a just and prosperous society (Hartanti, 2007). So, it is not an exaggeration if Romli Atmasasmita said that "corruption in Indonesia has become a virus that has been eating away at the whole government body since the 1960s until now and eradication measures are still halting" (Atmasasmita, 2004). When viewed conceptually, the beginning of the formation and regulation of the criminal act of corruption (UU Tipikor) in Indonesia, in addition to imposing penalties on corruption perpetrators, it also has the aim of restoring state losses that have been caused by the criminal act of corruption that has occurred. In addition, the political situation and public demands urged the government to immediately tackle the problem of corruption in Indonesia which then ended with the issuance of Law no. 31 of 1999 concerning Corruption Crime which was later amended and supplemented by Law No. 20 of 2001 (hereinafter referred to as the Corruption Act).

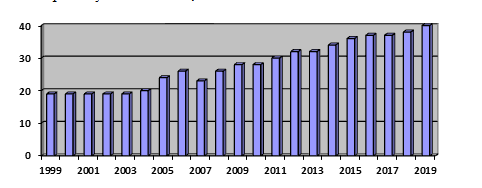

However, the current dilemma is the fact that this goal has not been effective, apart from the fact that enforcement still seems selective and the ratio between the budget spent by the state for eradicating corruption is very large compared to the return of state financial losses which are classified as very high. small, which in 2012 said that the budget spent in the effort to eradicate corruption in the 2001-2009 period was Rp. 73.1 trillion, while the state financial loss that returned in the same time frame was Rp. 5.3 trillion (Pradiptyo, 2012). The ineffectiveness of steps taken in eradicating this is reinforced by the Corruption Perception Index in Indonesia which is still relatively high, namely 40 (forty) in position 85 out of 180 countries in the world (kpk.go.id).Thus the authors say the Corruption Perceptions Index in Indonesia from 1999-2019 sourced from Transparency International, 2020:

As the author explained earlier, that there is an intersection between Article 21 of the AP Law and Article 3 of the Corruption Law Jo Article 5 and Article 6 of Law Number 46 of 2009 concerning the Corruption Crime Court (Corruption Court Law), intersections between article 21 of the AP Law and Article 3 of the Law Corruption in some literature is often referred to as conflict norm which ends in a dilemma between the norms of the two laws (UU Tipikor and UU AP). Often law enforcement officials also judge an act that is contrary to the principles of good governance (AUPB) only by referring to the parameters of an illegal act according to criminal law”.

This intersection of judicial authority then gets confirmation from Article 2 paragraph (1) of the Supreme Court Regulation Number 4 of 2015 concerning Guidelines for Procedures in the Assessment of Elements of Abuse of Authority which states that the PTUN has the authority to accept, examine, and decide the application for assessment whether or not there is abuse of authority in the Decree and/or Actions of Government Officials prior to criminal proceedings. Four words from before the criminal proceedings”. This word is the key word for limiting the intersection of authority to adjudicate abuse of power between the State Administration Court and the Corruption Court. However, “Perma Number 4 of 2015 does not provide an explanation of what is meant by criminal proceedings (Suhariyanto, 2018). It can be explicitly interpreted that the limitation in the form of the provision "before the existence of a criminal process" seems to give the impression that "the criminal justice process can override the administrative court process related to the assessment of whether or not there is an abuse of power" (Epah, 2016).

Some examples of cases that resulted in the PTUN judge overriding the petitioner's petition in examining the abuse of authority accused to the applicant on the grounds that there had been a criminal process, including: First, petition on behalf of Andrey Tulu, Palangkaraya State Administrative Court Decision Number: 15/P/PW /2016/PTUN.PLK, through this decision the petitioner's petition to test whether or not the element of abuse of authority suspected of being concerned was rejected, by the judge one of the legal considerations used was that there was a criminal process currently underway at the Tamiang Layang District Attorney, which proven by the Investigation Warrant Number: PRINT-01/Q.2.16/Fd.1/07/2014 from the Head of the Tamiang Layang District Attorney, dated 1 July 2014,

Second, the case of abuse of authority that ensnared the former Minister of Religion Surya Darma Ali which was tested at the Jakarta State Administrative Court with Decision Number: 257/P/PW/2015/PTUN-JKT, "has decided on the petition to state the decision and/or action of a government official. whether or not there is an element of abuse of authority filed when the criminal case has been tried by the Corruption Court, is declared not accepted (niet onvankelijk verklaard) on the basis that in the criminal case it is also given the opportunity to prove himself not to abuse his authority, so that for the sake of legal unity with the verdict of the Tipikor Court, the TUN Court stated that it was not authorized to examine, decide and complete the application. According to Permana, based on the consideration of the decision of the Jakarta TUN Court, the criminal proceedings are referred to when the official has been tried or has become a defendant” (Permana, 2016).

Looking at some examples of cases that the authors describe above, it can be concluded that the eradication of corruption in Indonesia currently tends to use the criminal paradigm (Criminal Centris) with the aim of deterring perpetrators and providing lessons. In addition to this approach and paradigm contradicting the principle of criminal law as the last tool (Ultimum Remidium) after other legal sanctions are applied, in fact the paradigm is not significantly effective in eradicating criminal acts of corruption in Indonesia, it is also less effective in efforts to recover actual state financial losses. became one of the objectives of the enactment of the Anti-Corruption Act in 2001 (Amirudin, 2012). The author's argument regarding the criminal paradigm of efforts to eradicate corruption in Indonesia today is further strengthened by the issuance of Supreme Court Regulation 4 of 2015 concerning Guidelines for Procedures in the Assessment of Elements of Abuse of Authority, which in Article 2 Paragraph (1) states that the State Administrative Court has the authority to accept, examine, and decide on the appraisal application whether or not there is an abuse of authority in Decisions and/or Actions of Government Officials before the existence of a criminal process. In fact, such a paradigm has proven ineffective in efforts to recover state losses resulting from criminal acts of corruption which are also one of the goals of eradicating corruption and the formation of the Corruption Act (Pradiptyo, 2012). The explanation above is also in line with the views of Addink & Berge, who in their writing states that in the world both at the national and global levels, so far in essence only discussing repressive criminal approaches to corruption and there is no real discussion of the preventive and repressive aspects of the approach. Administrative law concerned more or less states as follows: “....... in essence only the penal repressive approach to corruption was discussed and there was no real discussion about the preventive and repressive aspects of the administrative law” (Addink & Berge, 2007).

Methods

This research is a normative legal research. This study confirmed that "the appropriate approach used in this legal research is the statute approach, the case approach, and the conceptual approach". In this study, researchers used techniques. The data collection technique used in this study was a document study. This study uses the technique of analyzing legal materials with deductive logic, according to Peter Mahmud Marzuki who quoted Philipus M. Hadjon's opinion explaining the deduction method as the syllogism taught by Aristotle, the use of the deduction method stems from the submission of the major premise (general statement) then put forward the premise minor (special nature) of the two premises and then draw a conclusion or conclusion.

Discussion

At the beginning of the recognition of administrative law, it is also known as the Traditional or Classical State Administration which was pioneered by the figure of state administration science namely Woodrow Wilson with his work "The Study of Administration" (1887), in his book Woodrow Wilson argues that the main problems faced by the government executive is low administrative capacity. To develop an effective and efficient government bureaucracy, it is necessary to reform the government administration by increasing the professionalism of state administrative management. For this reason, knowledge is needed that is directed at carrying out bureaucratic reform by producing a professional and non-partisan public apparatus. Therefore, the dominant theme of Wilson's thinking is the politically neutral apparatus or bureaucracy (Amirudin, 2012). State administration must be based on scientific management principles and separate from the hustle and bustle of political interests. This is what is known as the political and administrative dichotomy concept. State administration is the implementation of public law in detail and in detail, because it becomes the field of technical bureaucrats. While politics is the field of politicians (Amirudin, 2012). The basic ideas or principles of the Old State Administration were:

1. Government focus on public services directly through government agencies.

2. Public and administrative policies are concerned with the formulation and implementation of policies with single and politically formulated objectives.

3. Public administration has a limited role in policy making and governance, public administration is more burdened with the function of implementing public policies.

4. The provision of public services must be carried out by administrators who are responsible to “elected officials” (political officials/bureaucrats) and have limited discretion in carrying out their duties.

5. State administration is accountable democratically to political officials

6. Public programs are implemented through a hierarchical organization, with managers exercising control from the top of the organization.

7. The main values of public organizations are efficiency and rationality.

8. Public organizations operate as a closed system, so that citizen participation is limited.

9. The role of the public administrator is defined as a POSDCORB function.

Then the concept of administrative law that we know today is administrative law with the New Public Management (NPM) paradigm, this concept emerged in the 1980s and strengthened in the 1990s until now. The basic principle of the NPM paradigm is to carry out state administration in the same way as moving the business sector (run government like a business or market as collaboration to the ils in the public sector). This strategy needs to be implemented so that the old model of bureaucracy that is slow, rigid and bureaucratic is ready to answer the challenges of the globalization era.

The New Public Service (NPS) paradigm is a concept that was created through the writings of Janet V. Dernhart and Robert B. Dernhart entitled "the new Public Service: serving, not steering" published in 2003. The NPS paradigm is intended to counter the administrative paradigm that becomes The current mainstream is the New Public Management paradigm with the principle of "run government like a business". According to the NPS paradigm, running government administration is not the same as a business organization. State administration must be moved as moving a democratic government. The mission of public organizations is not only to satisfy service users (customers) but also to provide goods and services as the fulfillment of public rights and obligations. The NPS paradigm treats public users of public services as citizens (citizens) not as customers (customers). State administration is not just how to satisfy customers but also how to give citizens the right to get public services. The perspective of the NPS paradigm, according to Dernhart, was inspired by: 1. The theory of democratic politics, especially those related to the relationship of citizens with the government, and; 2. Humanistic approach to organizational and management theory.

The NPS paradigm views the importance of the involvement of many actors in the administration of public affairs. In public administration what is meant by the public interest and how the public interest is realized does not only depend on state institutions. The public interest must be formulated and implemented by all actors, be it state, business, or civil society. This kind of view has made the NPS paradigm known as the Governance paradigm. Governance theory has the view that the state or government in the global era is no longer believed to be the only institution or actor capable of efficiently, economically and fairly providing various forms of public services so that the Governance paradigm views partnerships and networks among many stakeholders. in carrying out public affairs.

State administration can be understood as a process or as an institution. Said to be a process, if the state administration is related to all activities of administering government power. Meanwhile, when it is said to be an institution, state administration is generally interpreted according to various perspectives and approaches, which reflect "doctrine, a set of values and a set of procedures". In general, the various perspectives, as the author said before, are humanistic approaches that can be in the form of: organization, management, politics and law (David, 1993). The management perspective adopted in the field of administrative law (bestuur) which is administrative, managerial, bureaucratic and emphasizes the values of representation and responsiveness. Meanwhile, the part that is legal in nature and emphasizes constitutional integrity on the one hand and on the other hand also emphasizes substantive and procedural protection for individuals (Susanto, 2015).

Starting from the understanding of the significant position and role of the state administration or bureaucracy, the actual problem of state administration has a lot to do with the use of the power it has with the ability of the state administration to carry out this authority in a professional manner. Various problems that can be easily observed that are currently happening in the State Administration in Indonesia include the proliferation of corruption, the politicization of the bureaucracy, the euphoria of regional autonomy, and the dysfunction of people's political participation (Susanto, 2015). So the relevant question is, can state administrative law be an alternative weapon in preventing and eradicating corruption and the politicization of the bureaucracy in Indonesia? The problems that the authors describe, especially regarding corruption and abuse of authority by state or regional officials, show that there is something wrong with the concept of administrative law in Indonesia in preventing this from happening.

So it is not surprising that Lord Acton is of the view that "Power tends to be corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely". Of course, it makes sense to see the position and role of the state or bureaucracy which is very significant, this condition will of course depend on the role of the state government to prevent dysfunction in the bureaucracy and reform itself from a means of achieving goals to goals itself (government that is clean practices of corruption, collusion and nepotism). Talking about the eradication of corruption through the administrative law approach is currently widely used by countries in the world, as the author said at the beginning, apart from seeking preventive measures, also by changing the orientation that is deterrent towards recovering state financial losses. In terms of preventive measures, Mexican administrative law refers to the scope of internal control, which can be understood as a set of policies and procedures established by an institution to obtain adequate assurance that it will meet the proposed objectives. Internal control and supervision is exercised by bodies within the administrative body (Marquez, 2015).

In dealing with the problem of corruption, the Mexican government has established a special administrative structure in the inter-organic and intra-organic spheres of the country. The Mexican government exercises internal and external controls, such as establishing social defense institutions in fighting corruption or actions against corrupt practices, these agencies are given special functions: assistance from internal control agencies in management, internal control and evaluation of public administration performance; external regulatory body has the right to conduct external audits; that is, reviewing the benefits of spending on state finances using government audit techniques, reviewing public accounts, and evaluating their activities. two paradigmatic examples of this are the ministry of Public Administration and the federal office of the Mexican auditors (Marquez, 2015). Based on the 2012-2013 Progress Report 1, the Ministry of Public Administration has focused on closing the gaps in corruption within the Mexican state apparatus, not only those that can arise from interactions between civil servants and citizens during routine activities related to goods and services provided or obtained from government, but also things that are caused by not fulfilling the responsibilities of government officials in the field of public administration.

In terms of internal supervision in government and the bureaucracy as an effort by the state to minimize abuse of authority which results in losses to the state, Indonesia already has institutions that are given the authority to do so, but there are still shortcomings and problems that need to be addressed, especially in terms of the supervision model, technical loss recovery state finances and sanctions. Following this the author will explain and explain about internal and external supervision in efforts to prevent and eradicate corruption in the Indonesian government, and its shortcomings:

Internal Supervision in Efforts to Eradicate Corruption within the Scope of Indonesian Government & Bureaucracy

In practice, the calculation of state losses is carried out by several agencies, namely the Supreme Audit Agency (BPK) based on Law Number 15 of 2006 concerning the Supreme Audit Agency (hereinafter referred to as the BPK Law) and the Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus/APIP (BPKP, Inspectorate General, and Provincial and Regency/City Inspectorates) based on Government Regulation no. 60 of 2008 concerning Government Internal Control Systems (hereinafter referred to as PP SPIP). The BPK institution was formed based on the mandate of the 1945 Constitution, the BPK has the duties and authorities stipulated in Article 6 to Article 11 of the BPK Law. In Article 6 paragraph (1) it is stated that the task is “BPK is tasked with examining the management and accountability of state finances carried out by the Central Government, Regional Governments, other State Institutions, Bank Indonesia, State-Owned Enterprises, Public Service Agencies, Regional Owned Enterprises, and other institutions or agencies that manage state finances”. Meanwhile, the authority of the BPK, in Article 10 paragraph (1) letter a, states, "The BPK assesses and/or determines the amount of state losses caused by acts against the law, whether deliberately or negligently committed by the treasurer, BUMN/BUMD managers, and other institutions or agencies. which organizes the management of state finances ".

In this discussion, the BPK institution was not the focus of discussion because in accordance with the Government Administration Law, related to the supervision of abuse of authority to government agencies and/or officials given authority is the Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus (APIP). Discussions regarding the BPK only when needed or as a complement and comparison to the authority of APIP. This needs to be pointed out because APIP in part of its authority also has the authority to calculate state financial losses in addition to the BPK. In accordance with Article 20 paragraph (2) of the Government Administration Law, it is stated that the results of APIP supervision can be in the form of "there are administrative errors that cause losses to state finances". APIP is a functional supervisor that is internal in nature, because it is in a supervised institutional environment, namely the government environment. The supervision carried out by each APIP agency is regulated in a separate regulation, namely Presidential Regulation Number 192 of 2014 concerning the Financial and Development Supervisory Agency, Presidential Regulation No. 7 of 2015 concerning the Organization of State Ministries, and Government Regulation No. 18 of 2016 concerning Regional Apparatus. The supervision and examination according to the elucidation of Article 116 of the Presidential Decree No. 54 of 2010 is intended to:

a. Improving the performance of the government apparatus, creating a professional, clean and responsible apparatus;

b. Eradicate abuse of authority and practices of KKN; and

c. Enforcing applicable regulations and securing state finances.

However, to understand the three regulations must refer to the State Treasury Law, Law Number 15 of 2004 concerning Audit of State Financial Management and Responsibility (hereinafter referred to as Law No.15 of 2004), and PP SPIP, because of these three regulations the agency is said to be APIP (Amirudin, 2012). In accordance with the duties, functions, or authorities possessed by APIP. This institution is the supervisor of the implementation of duties and functions of government agencies including accountability for state finances through the process of auditing, reviewing, evaluating, monitoring and other supervisory activities. then in practice, this APIP by law enforcement officials also often coordinates to calculate state financial losses. Apart from APIP, it is also possible for law enforcement officers to coordinate with the help of external auditors/public accountants in calculating state financial losses.

In PP SPIP, APIP when carrying out its duties can go through an audit. This method of audit implies the same meaning as the examination contained in the State Treasury Law. In Article 48 and Article 50 PP SPIP, it can be said that it has copied and pasted from Article 4 of Law no. 15 of 2004. In this case it can be seen in the PP SPIP below:

a. In Article 48 paragraph (2) it is stated that, APIP in carrying out internal supervision through: auditing, reviewing, evaluation, monitoring, and other supervisory activities.

b. Article 50 paragraph (1) states that the audit referred to in Article 48 paragraph (2) consists of: performance audits and audits with specific objectives.

c. Article 50 paragraph (2) states that the performance audit as referred to in paragraph (1) letter a is an audit of the management of state finances and the implementation of the duties and functions of Government Agencies which consist of aspects of efficiency, efficiency, and effectiveness. performance audit on the management of state finances, among others:

1) Audits of budget preparation and implementation;

2) Audits of the receipt, distribution and use of funds; and

3) Audit of asset and liability management. Then the performance audit on the implementation of duties and functions, including auditing the activities to achieve goals and objectives.

d. Article 50 paragraph (3) states that audits with specific objectives as referred to in paragraph (1) letter b include audits that are not included in the performance audits as referred to in paragraph (2). Audits with specific objectives include investigative audits, audit operations SPIP, and audits on other matters in the financial sector.

Likewise in Law no. 15 of 2004, the contents are the same as those contained in the PP SPIP. For that it can be seen in Article 4 of Law no. 15 of 2004 following:

a. Article 4 paragraph (1) states that the examination of the management and accountability of state finances consists of: financial audits, performance examinations, and audits for specific purposes.

b. Article 4 paragraph (2) states that financial audit is an examination of financial reports.

c. Article 4 paragraph (3) states that performance inspection is an examination of the management of state finances which consists of examining economic and efficiency aspects as well as examination of effectiveness aspects.

d. Article 4 paragraph (4) states that an examination with a specific purpose is an examination which is not included in the examination as referred to in paragraph (2) and paragraph (3).

In his explanation, it is explained that an examination with a specific purpose includes, among others, examination of other matters in the financial sector, investigative examination, and examination of the government's internal control system. Specifically for investigative examinations, namely examinations to reveal indications of state/regional losses and/or criminal elements. Therefore, from the two regulations there is a similarity in the definition of audit owned by APIP with audits (financial audits, performance audits, and audits for specific purposes) owned by BPK, when this APIP performs the function of calculating state losses, theoretically it will cause problem, namely APIP is an institution formed based on PP SPIP while BPK was formed based on the 1945 Constitution Jo. Law (Law No. 15 of 2004 and the BPK Law), so that in terms of lex specialists and lex superior, BPK has more authority to calculate state losses.

If seen in Article 9 paragraph (3) of Law no. 15 of 2004 Jo. Article 9 paragraph (1) letter g of the BPK Law, BPK can use external examiners and/or experts, namely examiners and/or experts from outside the BPK who work for and on behalf of BPK. This means that based on the mandate, the BPK can ask for assistance from other parties to assist the BPK in calculating state/regional losses. What is meant by examiners and/or experts from outside the BPK are examiners and/or experts in certain fields from outside the BPK, such as within the government internal control apparatus, examiners, and/or other experts who meet the requirements determined by the BPK. The use of the examiner who comes from the government internal control apparatus must be in accordance with the official duties, namely there is an assignment of the leadership of the agency concerned. To avoid debates regarding whether or not APIP is authorized to assess state losses, here will be mentioned the legal basis used by APIP in assessing state financial losses, namely:

a. Law No. 30 of 2002 concerning the Corruption Eradication Commission (Article 6)

b. Government Regulation No. 60 of 2008 concerning Government Internal Control System (Article 50 paragraph (1) letter b).

c. Presidential Regulation No. 192 of 2014 concerning the Financial and Development Supervisory Agency (Article 27).

d. Constitutional Court Decision No. 003/PUU-IV/2006, spoken on July 25, 2006.

e. Constitutional Court Decision No. 31/PUU-X/2012, pronounced on 23 October 2013.

f. Regulation of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform No. PER/05/M.PAN/03/2008 concerning Auditing Standards for Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus (in Appendix) Jo. (Article 53 PP SPIP).

g. Memorandum of Understanding between the RI Prosecutor's Office, the Indonesian Police, and the BPKP with No. KEP-109/A/JA/09/2007, No. Pol-B/2718/IX/2007, No. KEP1093/K/D6/2007 dated 28 September 2007 concerning Cooperation in Handling Cases of Irregularities in State Financial Management with Indication of Corruption, Including Non-Budgetary Funds.

h. The Indonesian Government Internal Audit Standards issued by the Indonesian Government Internal Auditor Association (AAIPI). (Article 53 PP SPIP Jo. Permen PAN No. PER/05/M.PAN/03/2008).

If APIP is maintained that it does not have the authority to assess state financial losses, then the results of supervision by APIP in Article 20 of the Government Administration Law are meaningless. However, the APIP findings in calculating state losses are different from those of BPK. At least these differences can be seen in the criteria below:

a. The findings of the APIP are still administrative in nature because these findings are in the framework of supervision, not in order to calculate state losses accompanied by pro justicia or commonly known at the request of law enforcement officials.

b. APIP cannot carry out direct prosecutions such as demands for BPK compensation to the Treasurer.

c. APIP also cannot make claims for compensation to civil servants who are not treasurers and other officials, because these demands fall under the authority of the President, the Minister of Finance as BUN, the Minister/Head of Institutions (delegated to the Head of the Work Unit), and the Governor/Regent/Mayor (delegated to Head of Regional Financial Management Work Unit as BUD).

d. When connected with Article 12 of Law no. 15 of 2004 and Article 4 letter b of Government Regulation no. 38 of 2016 concerning Procedures for Claims for Compensation for State/Regional Losses Against Non-Treasurer Civil Servants or Other Officials, the implementation of SPIP and APIP is a study material for BPK and PPKN/D (State/Regional Financial Settlement Officials).

Then when this APIP finds out about the state's financial loss? The supervision carried out by APIP as mentioned above, consists of auditing, reviewing, evaluation and monitoring. The four ways of monitoring, APIP can find out the existence of state financial losses through reviews and audits. Through a review, APIP conducts a review of the Financial Statements of the Central Government, Ministries/Institutions and Regional Governments, namely before the Minister of Finance submits to the President, before the Minister/Head of Institutions submits to the Minister of Finance, and before the Governor/Regent/Mayor submits to the BPK. Through the review, it is not easy to find state financial losses because the review only examines the financial reports that have been made, so it requires accuracy and experience/expertise from APIP as well as supporting evidence for these financial reports If APIP is in doubt about the review it has done, APIP can follow up by using an audit to find out a state financial loss.

Monitoring that is easy to find indications of state financial losses is through audits, both performance audits and audits with specific objectives (investigative audits). In accordance with its function, through the APIP audit it can assess the truth, accuracy, credibility, effectiveness, efficiency of the correctness of financial management and the implementation of government duties and functions. Through audits, it can also be seen how much revenue and expenditure on state finances, including the effectiveness and efficiency of the government's performance in budgeting state finances. Based on the Audit Standards for the Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus, the objective of the performance audit is to assess that auiditi has carried out its activities economically, efficiently, and effectively, so that the performance audits examined are the financial and operational aspects of the fluidity. Different from performance audits, investigative audits are used to reveal irregularities that have resulted in state/regional financial losses, so that what is examined includes the facts and processes of the incident, the causes and effects of deviations, determining the parties involved or responsible for these deviations. Therefore, if there is an activity with a small scope and should require a small number of apparatus and a sufficiently large budget is available in it, however, the budget is spent arguing for budget absorption on the grounds that it is more optimal, it is suspected here that there is ineffectiveness, and inefficiency in implementing budgeting and budget absorption in these activities.

In fact, the method that uses administration as an instrument has also been applied for a long time in several countries in the world, if at the beginning the author gave an example of Mexico, then the author also compares it with countries in the world with high levels of prevention and a low chance of corruption, where corruption control has been largely achieved and acts of corruption can be managed successfully, such as Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom (Pippidi, 2013). These countries control opportunities for corruption through transparent administration and economies, reduce official positions, and less opportunity for discretionary spending (Pippidi, 2013).

The Netherlands, for example, has changed its views on corruption, partly because of the role of the country's DPR. This is because of the extensive investigations carried out by the Dutch Parliament during the 2002-2005 period. in an attempt to uncover the biggest scandal in modern Dutch history, namely in the form of public building fraud. It started when a television program, in which a whistle blower disclosed information about corrupt practices in the government construction sector and public road projects on 5 February 2002, the Dutch Parliament then decided to form a Fact-Finding Committee for the Construction Industry. The Committee concluded that there were many irregular fraudulent tenders, in which the decision-making of civil servants and politicians was influenced by prizes of any kind, was a common practice (Adiink & Berge, 2007).

Subsequently, the Committee decided to investigate the nature and scope of the alleged deviation and more specifically to check all relevant facts about the construction of the Schiphol railway tunnel. The sheer number of uncovered irregularities shocked the Committee, and concluded that the construction sector was largely affected by practices that went against the regulations on fair trade economics. Initial talks between companies aimed at reaching an agreement on prices and market share and duplicate bookkeeping practices suggest that most large construction firms are forming structures that can lead to cartels. For violating competition regulations, the construction company was fined by the Netherlands Competition Authority (NMA). Finally, the government sued on the argument that because of suspicion there was a cartel agreement the government had paid too much for the project and they demanded compensation (Adiink & Berge, 2007).

The Committee concluded that there was no indication of structural civil servant corruption of any kind. However, the Committee is concerned about a small number of integrity violations committed by a small number of civil servants. Furthermore, it is suspected that the relationship between civil servants and construction companies is too close and can cause collusion. Therefore, regulations for civil servants and public procurement were sharpened. The actual circumstances regarding the shift in methods of combating corruption in the Netherlands as described above are partly based on the report "Corruption in the Circle of Public Service in the Netherlands" ordered by the Dutch Government which was published in May 2005 and which was due to international criticism of the Dutch Corruption Policy. This study mainly focuses on the quantitative factual aspects and criminal law of corruption in the Netherlands. At that time much attention was paid to the repressive aspect rather than the aspect of preventing corruption (Adiink & Berge, 2007).

Fundamental aspects of administrative law (preventive or repressive) related to corruption were still lacking in the provisions in the Netherlands at that time. Within the framework of the administrative legal system the administrative authority has the competence to make preventive or repressive decisions on corruption in the public sector. Administrative law instruments can be used in a much more effective and direct manner compared to criminal law mechanisms which generally take a long time, often several years. The consequence of the analysis of the situation in the Netherlands is that only the most serious corruption cases will be brought to the Court (Adiink & Berge, 2007).

When compared with cases and characteristics of corruption eradication in the Netherlands, it can be said that in addition to corruption is a long-standing and rooted problem in almost all countries in the world, so far the approach often used is the approach to the concept of criminalization however, what is often forgotten is that the models and types of corruption have taken a broader perspective in terms of the various types of corruption that occur. This development requires a critical look at traditional legal norms where corruption is punished repressively using criminal law instruments and which must be adopted by administrative law (Adiink & Berge, 2007). Two developments can be distinguished. First, attention is paid not only to the repressive approach to corruption, but also to ideas that have been developed related to the approach to preventing corruption and most importantly the problem of returning state assets that have been stolen due to corruption which is the goal of eradicating corruption in the world.

External Control

External supervision is supervision carried out by a supervisory institution/body that is outside the supervised institution (in this case, outside the government) (Amirudin, 2012). The author feels this is very necessary in the effort to eradicate corruption in Indonesia, especially in the government sector. In this case in Indonesia is the Supreme Audit Agency (BPK), which is a high state institution that is independent from the influence of any power. In carrying out its duties, the BPK does not ignore the results of the audit reports from the government internal control apparatus, so it is only fitting that there is a need for harmonization in the state financial supervision process. This harmonization process does not reduce the independence of BPK from taking sides and objectively assessing government activities. Legislative oversight is the supervision carried out by the people's appraisal institution both at the central level (DPR) and at the regional level (DPRD). Supervision is dominated by supervision from a political point of view. Meanwhile, community supervision is. (Santoso, 2016) However, what is no less important is the supervision carried out by the community through special channels provided or other available media. In general, in every government policy, it is always possible to carry out public supervision (Santoso, 2016). As is well known, since the launch of the reform era in May 1998, many people think that significant changes have not been fully seen.

The presence of state auxiliary agencies or often referred to as The Fourth Branch of Government as one of the implications of the reform era, it illustrates that the winds of change seem to be bringing this nation towards real change. At least, the birth of several state auxiliary agencies such as the National Human Rights Commission (KOMNAS HAM), the Independent Broadcasting Commission (KPI), the General Election Commission (KPU), the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), the National Ombudsman Commission (KON), the Law Commission National (KHN), the Commission for the Supervision of Business Competition (KPPU), and the National Commission for Child Protection (KOMNAS Anak) show that there is something new in the constitutional practice of the Republic of Indonesia.

There are several reasons behind the birth of these sampiran institutions. The formation of the KPK through Law Number 30 of 2002 concerning the Corruption Eradication Commission, for example, is due to the fact that existing government institutions, both the prosecutor's office and the police, have not functioned effectively and efficiently in dealing with corruption. Meanwhile, Komnas HAM, although Law Number 39 of 1999 concerning Human Rights and Law Number 26 of 2000 concerning Human Rights Courts does not provide a clear description of the reasons for the formation of this commission, it can be concluded from several articles contained in the two laws. whereas the formation of the National Commission on Human Rights was motivated by three things, namely, first, the efforts to recover from the losses incurred as a result of gross human rights violations which are classified as extra ordinary crime have not been maximized. Second, conditions conducive to the implementation of human rights have not yet been developed. Third, there is still weak protection and enforcement of human rights in Indonesia. It can be concluded that the emergence of various kinds of secondary state institutions is mainly due to the high public distrust of existing state institutions because they are deemed not functioning optimally, especially in supporting the reform agenda. Like mushrooms in the rainy season, these state auxiliary organs thrive in various fields of Indonesian state. Not a few lawmakers create state auxiliary organs. The form of experimentation of this institution is the council, commission, committee, board, or authority. Ryaas Rasyid said that: (Huda, 2007)

“The phenomenon of the proliferation of state commissions gives the impression that Indonesia is in a state of emergency because the various existing institutions have not played a role and are running effectively in accordance with the state administration and the constitution. The DPR has not been able to carry out its supervisory function on the performance of state institutions that are under the executive branch. On the other hand, the quasi-state institution is a breakthrough as well as a manifestation of the distrust of the people and state leaders towards existing state institutions”

However, a different view was conveyed by Andi Mallarangeng. According to Andi Mallarangeng, "the existence of a quasi state institution is a natural answer to the modern constitutional process of the trias politica structure. In the development of the state, it is not enough just the legislative, executive and judiciary institutions. This is due to the lack of a horizontal accountability mechanism between these institutions” (Huda, 2007). Some people think that the emergence of state auxiliary organs in Indonesia, which mostly function as supervisors for the performance of state institutions, is a form of distrust of existing supervisory agencies, especially law enforcement institutions and the fact that government bureaucracy can no longer meet the demands of the public's need for public services. with increasing quality standards, effective, and efficient. For example, the National Ombudsman Commission was born because of the public's distrust of convoluted bureaucratic services, when public trust in handling cases of human rights violations gave birth to the National Commission on Human Rights, and the birth of the Corruption Eradication Commission was caused by an existing state institution, namely the prosecutor's office. and the police have not functioned effectively and efficiently in handling corruption cases.

So in an effort to prevent and eradicate corruption in Indonesia, especially in the government sector (both central and regional), a serious external supervision is needed and if a state loss is found by the BPK as a result of abuse of authority, action must be taken immediately to recover the financial loss, taking a comparative example in the Netherlands where extensive investigations were carried out by the Dutch Parliament during the period 2002-2005, in an effort to uncover the biggest mega-corruption scandal in modern Dutch history, namely in the form of public building fraud which resulted in the return of state financial losses due to the scandal.

Sanctions

Sanctions are an important part of legislation. The regulation of sanctions in the body of statutory regulations is intended so that all provisions that have been formulated (regulated) can be implemented in an orderly manner and are not violated. Legislations in the field of administrative law always give authority to government agencies to enforce sanctions, whenever there is a violation of the norms of applicable administrative law (Susanto, 2019). Sanctions are described as: "the rules that determine the consequences of non-compliance or associated norm violations" (de sanctie wordt gedefinieerd als: "regels die voorschrijven welke gevolgen aan de niet naleving of deovertreding van de normen verbonden worden"). These sanctions are used as a means of power that seeks to comply with/comply with norms and these efforts are aimed at minimizing losses caused by violating norms. Romanian legal literature defines sanctions as: “the sanction as a consequence of not observing a rule of conduct prescribed or sanctioned by the state” (sanctions as a consequence of not complying with the rules of conduct determined or approved by the state) (Verstraeten, 1990).

The international amnesty states that the sanctions are: “sancties zijn alle maatregelen, zoals juridische straffen en disciplinaire straffen, waarmee negatief wordt gereageerd op ongewenst gedrag” (Sanctions are all actions, such as legal and disciplinary sanctions, that respond negatively to unwanted behavior). As the importance of sanctions in a statutory regulation described by the experts above, however, if we look at the regulation regarding the abuse of power which results in state financial losses in Article 20 jo 21 of Law Number 30 of 2014 concerning Government Administration, it has not clear sanctions instruments can be applied in the event of an abuse of authority that causes losses to state finances by government officials. Thus the authors describe the norms in each of these articles

Article 20:

(1) Supervision of the prohibition of abuse of authority as referred to in Article 17 and Article 18 is carried out by the government internal control apparatus.

(2) The results of the supervision by the government internal control apparatus as intended in paragraph (1) are in the form of:

a. there is no error;

b. there is an administrative error; or

c. there is an administrative error that causes loss to state finances.

(3) If the results of the supervision of the government internal apparatus are in the form of administrative errors as referred to in paragraph (2) letter b, a follow-up will be carried out in the form of administrative improvements in accordance with the provisions of laws and regulations.

(4) If the results of the supervision of the government internal apparatus are in the form of administrative errors that cause losses to state finances as referred to in paragraph (2) letter c, a refund of the state financial losses shall be carried out no later than 10 (ten) working days as of the decision and issuance of the results of the supervision..

(5) The return of state losses as referred to in paragraph (4) shall be borne by the Government Agency, if the administrative error as referred to in paragraph (2) letter c occurs not due to an element of abuse of authority.

(6) The recovery of state losses as referred to in paragraph (4) shall be borne by the Government Official, if the administrative error as referred to in paragraph (2) letter c occurs due to an element of abuse of authority.

The category of sanctions that is given if an element of abuse of authority is found is a severe administrative sanction, this is regulated in Article 80 Paragraph (3) of the Government Administration Law, as regulated in Article 81 of the Government Apparatus Law, sanctions can be divided into 3 (three) categories:

Article 81

(1) Minor administrative sanctions as intended in Article 80 paragraph (1) are in the form of:

a. verbal warning;

b. written warning; or

c. postponement of promotion, class, and/or rights of office.

(2) The administrative sanctions as meant in Article 80 paragraph (2) are in the form of:

a. payment of forced money and/or compensation;

b. temporary dismissal by obtaining office rights; or

c. temporary dismissal without obtaining office rights.

(3) Heavy administrative sanctions as intended in Article 80 paragraph (3) are in the form of:

a. permanent discharge by obtaining financial rights and other facilities;

b. permanent discharge without obtaining financial rights and other facilities;

c. permanent dismissal by obtaining financial rights and other facilities and being published in the mass media; or

d. permanent dismissal without obtaining financial rights and other facilities as well as being published in the mass media.

(4) Other sanctions in accordance with statutory provisions.

If we interpret it through grammatical techniques, then if in a case if there is an abuse of authority that causes loss to the state or not, the government official concerned will only be terminated and not obliged to return the state's financial losses as a result of his actions, this is certainly contrary to the spirit. recovering state financial losses as one of the spirit of corruption eradication in the world and Indonesia. As for Article 21 of the AP Law only regulates the authority of the State Administrative Court in examining the elements of abuse of authority carried out by government officials and the procedure for filing it. So according to the author it is necessary to make an effort to revise the AP Law in order to make improvements to the substance so as not to cause legal certainty related to administrative sanctions if a loss of state finances is found as a result of abuse of authority committed by government officials, this is in line with the view of Berndard L. Tanya & Theodorus Y Parera, that is: “The substance of the law is the starting point for the law enforcement process (guidelines for law enforcement officers in carrying out law enforcement duties), so the quality of a legal rule to a certain degree will determine the enforcement process in law enforcement” (Tanya & Parera, 2018). In his book Panorama Law and Legal Studies, Bernard L Tanya & Theodora Y Parera stated that if the law is not qualified, it is prone to deviations in a pathological structure. According to him, legal pathological seeds are often found and have also been started since a regulation was initiated. Very often, the making of a rule of law is driven by a momentary emotional reactive attitude without considering its relevance and significance in a wider context. In addition, sometimes the making of academic drafts is often carried out hastily and is only considered a legal drafting project, even though the content of the rules is much broader and richer which requires careful study and must involve as many relevant experts as possible.

So through this paper, in an effort to eradicate and prevent corruption as a result of the abuse of authority carried out by government officials through the administrative law approach, a seriousness between the government and political leadership is needed, As for the concept of eradicating corruption through an administrative legal approach, including: First, strengthening the internal supervision of the government, in this case the one who performs the task and authority is the Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus (APIP) in a way that if APIP finds an abuse of authority that causes losses to state finances, APIP is given the authority to carry out direct prosecutions and APIP is given the authority to make claims for compensation to non-treasurer civil servants and other officials, because these demands fall under the authority of the President, the Minister of Finance as BUN, the Minister/Head of Institution (delegated to the Head of the Work Unit), and the Governor/Regent/Mayor (delegated to the Head of Regional Financial Management Work Unit as BUD).

Second, with regard to external supervision, in the event that the Financial Supervisory Agency (BPK) finds state financial losses, it would be good and appropriate to take administrative action with an orientation to return the state's financial losses and not only through a repressive approach or through criminal channels, this can be done. by communicating with APIP for time efficiency in eradicating corruption and recovering state financial losses. Third, as the authors state above that the importance of sanctions in a statutory regulation, however, if we look at the regulation regarding the abuse of authority which results in state financial losses in Article 20 Juncto 21 Law Number 30 of 2014 concerning Government Administration, it has not provided clear sanctions instruments can be applied in the event of an abuse of authority that causes losses to state finances by government officials. So a revision is needed with the aim of including a clear sanction instrument if an abuse of authority is found that results in state financial losses, for example: for officials who are proven to have committed violations and abuse of authority resulting in state financial losses, in addition to sanctions in the form of dismissal from their positions, they are also subject to financial losses (Amirudin, 2012).

Conclusion

The concept of eradicating corruption through an administrative law approach, namely: First, strengthening the internal supervision of the government body, in this case the one who performs these tasks and authorities is the Government Internal Supervisory Apparatus (APIP) in a way that if APIP finds an abuse of authority that causes losses to state finances, APIP is given authority to prosecute directly and APIP is given the authority to make claims for compensation. Second, with regard to external supervision, in the event that the Financial Supervisory Agency (BPK) finds state financial losses, it would be good and appropriate to take administrative action with an orientation to return the state's financial losses and not only through a repressive approach or through criminal channels, this can be done by communicating with APIP for time efficiency in eradicating corruption and recovering state financial losses. Third, the addition of sanctions in regulating the abuse of authority which results in state financial losses in Article 20 Juncto 21 of Law Number 30 of 2014 concerning Government Administration has not provided clear sanctions instruments that can be applied in the event of an abuse of authority that causes losses to state finances by officials. Government and only provide administrative sanctions in the form of dismissal and do not require repayment of state financial losses.

References

- Amiruddin, A. (n.d.). Eradication of corruption in the procurement of goods and services through criminal and administrative law instruments. Jurnal Media Hukum, 19(1).

- Atmasasmita, R. (2004). Around the problem of corruption in national aspects and international aspects. Bandung: Mandar Maju.

- Indra, P.T. (2016). Critical note on expansion of authority to adjudicate state administrative courts. (Yogyakarta: Genta Press)

- David, R. (1993). Public administration: Understanding, management, politics and law in the public sector. (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc,)

- Dupont, L., & Verstraeten, R. (1990). Belgian criminal law handbook. (Leuven : Acco).

- Elpah, D. (2016). The point of touching authority between the state administrative court and the corruption court in assessing the abuse of authority. (Jakarta: Puslitbang Hukum dan Peradilan MA).

- Addink, G.H., & Berge, J.B.J.M. (n.d.). Study on innovation of legal means for eliminating corruption in the public service in the Netherlands. Electronic Journal of Comparative Law, 11(1).

- Hartanti, E. (2007). Corruption crimes and law enforcement. Jakarta: Sinar Graphic Huda, Ni'matul. 2007. State Institutions in the Democratic Transition Period. Yogyakarta: UII Press.

- Ridwan, H.R. (2006). State administrative law. Jakarta: King Grafindo Persada.

- Daniel, M. (2015). Mexican administrative law against corruption: Scope and Future, Mexican Law Review, 8(1).

- Fodor, M. (n.d.). Elena general principles of administrative sanctions in the romanian law. Fiat Justitia Journal, 1(1).

- Alina, M. (2013). The good, the bad and the ugly: Controlling corruption in the European union. Advanced Policy Paper for Discussion in the European Parliament.

- Hari, S. (2018). Reconstructing Administrative Law System towards Serving Law, Legal Issues, 44(2).

- Anggoro, F. (2020). Testing elements of abuse of authority against decisions and/or actions of government officials by PTUN. Fiat Justisia Journal of Law, 10(4).

- Pradiptyo, R. (2012). Does corruption pay in Indonesia? If So, Who are Benefited the Most?, Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No. 41384.

- Putriyanti, A. (2019). “A study of government administration law in relation to the state administrative court. Pandecta, 10(2).

- Rakhmat, Md. (2014). Indonesian state administrative law. (Bandung: Prenadmedia)

- Saputra, M. (1988). State administrative law. Jakarta: Rajawali Press

- Suhendra A.T. (n.d.). Juridical Analysis of the Fourth Branch of Government in the State Administration Structure in Indonesia. Legal Discourse, 23(1).

- Suhariyanto, B. (2018). Intersection of Authority to Adjudicate Abuse of Discretion between TUN Court and Corruption Court. Journal of Law and Judiciary, 7(2).

- Bernard, L., & Parera, T. (2018). Panorama of law and legal studies. Yogyakarta: Genta Publishing.

- Alberto, V. (2019). The formal and informal institutions of corruption: An analytical framework and its implications for anticorruption policies. (Handbook edited by Enrico Carloni in collaboration with Diletta Paoletti, “Preventing corruption through administrative measures”, Morlacchi Editore U.P.