Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 2

Change Leadership and Followers Satisfaction in Selected Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria

Oluseye, Abiodun B, The Federal Polytechnic Ilaro, Nigeria

Bako Yusuf A, The Federal Polytechnic Ilaro, Nigeria

Taiwo, Akeem A, The Federal Polytechnic Ilaro, Nigeria

Ajibode, Ilesanmi A, The Federal Polytechnic Ilaro, Nigeria

Abstract

Change leadership is required for any change efforts to see the light of the day. This study is based on determining the extent to which change leadership may influence followers’ satisfaction in tertiary institutions in Nigeria. The research work makes use of cross-sectional survey using administered questionnaire. The respondents were selected randomly from selected institutions in Nigeria. 1497 copies of questionnaires were retrieved out of 1600 copies distributed which resulted in 93.5% return rate. Correlation and regression analysis were used to examine the effects of leadership concern for work, staff and work/staff combined (independent variables) on followership satisfaction (dependent variable). The result shows that there exists strong positive relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable. In addition, the result further revealed that all the independent variables have p-values < 0.05 significant level which indicates that the independent variables have significant effect on followership satisfaction, however, concern for work and staff combined have significant effect on followership compared to other independent variables. The study concludes that change leadership is second to none and indispensable machinery which can help tertiary institutions in achieving followers’ satisfaction.

Keywords

Change, Leadership, Followers, Satisfaction, Tertiary Institutions, Management.

Introduction

The concept of change and change management is very common in articles as well as newspapers today. Lorenzi & Reiley (2000) asserts that change management is the process by which an organization gets to its future state, its vision. Change management attempts to facilitate the process by which organizations gets to its distribution (Arendt et al., 2019). Therefore, creating change and then empowering individuals to act as change agent to attain that vision. Change leaders empower change management agents. These agents need plans that provides a total systems approach, which are realistic and are future oriented. Bunjak et al. (2019) opined that change leadership via visions and mission guides, instructs, directs, propels, stimulates, supervises, motivates, teaches and protects other change agents and followers towards the desired change. Followers play a huge role in the success or failure of any change effort (O’Driscoll, 2012).

Norazilawani & Hanum (2018) argues that there is marked difference in the orientation between management and leadership. Both involve deciding what needs to be done, developing the capacity to do it, and ensuring that it is done. However, while management is concerned with order and consistency, leadership is concerned with change. Olga et al. (2016) suggests that sometimes this does not happen. One reason for this is that leaders become so committed to a project or belief that they only attend information that supports their own position and fail to recognize signals that point to, for example, changes in customer requirements or the availability of resources. A history of past success can contribute to this condition. This encourages the leader to plough ahead without giving sufficient consideration to the needs or concerns raised by others (Olga et al., 2016).

It is obvious that not only is the pace of change increasing, but that there is also a shift in emphasis towards managing discontinuous or transformational change. An implication of this shift is that leadership and the provision of a sense of direction are becoming more important parts of managerial work (Oreg & Berson, 2019). During change, leaders are expected to recognise the need for change, identify change goals, communicate a sense of direction, formulate a change strategy, motivate people, provide support and create an organizational context conducive to change (Naiemah & Abdulsatar, 2018). Job satisfaction is a very widely studied phenomenon, described as being a pleasant or positive emotional condition, which is derived from an employee’s appreciation for his/ her occupation or work experience (Orthodoxia et al., 2019; Locke, 1976).

The trend in the higher education environment in Nigeria evident from yearly increase in the number of institutions of learning has called for good and effective human capital strategies in order to have best hands. Lecturers and other administrative staff are also potential leaders who must instill good morale in the young ones especially the students. Job dissatisfaction has frequently been cited as the primary reason for a high turnover of academics (Kestetner, 1994) as well as increased rates of strikes and absenteeism (Shawa et al., 2003) both of which impede efficiency and effectiveness, which in turn pose a threat to institutions of learning in Nigeria. It is worthy to note that leadership concern about work and even staff directly cause work outcomes that are either positive or negative. Either Positive work outcomes or negative work outcome those at the receiving end are students that rely on such services for skill acquisition for them to face challenges in their respective fields in future. Thus, it is a major duty of the leader of the institution to prevents these negative work outcomes for his/her vision/goals to be achieved within the shortest period of time. It is worthy to know that work satisfaction was found to be an important predictor of where academics intended to work because a leader that have concern for staff will make provision for majorly office equipment’s that are mostly absent in majorly all government institutions of learning in Nigeria. It is however believed that leadership of institutions of learning in Nigeria especially with concern for staff will have to do less work when it comes to his/her concern for work because staff that are well taking care of will definitely optimize his input in line with the administrator’s visions and goals. The premise being that satisfied workers will be more productive and remain within the organization longer, whereas dissatisfied workers will be less productive and more inclined to quit (Sarker et al., 2003).

As the new administrator comes to head the institution of learning, such administrator comes with new vision and goals. Hence, need to determine which leadership style is capable of enhancing employee’s morale such that the institution achieve its goals and objectives optimally. The leadership styles in higher institutions in Nigeria have been raised in many instances, by trying to find out the causes of poor standard of tertiary education in Nigeria. Majorly, most heads of the institutions forget that leadership style in the office is an outstanding determinant of the worker’s performance. This leadership chain also extends to lecturers and administrative staff who are expected to portray a good leadership style which would also serve as a determinant on the students’ academic performance.

There are different leadership styles and possible conditions which can be applied in an organization and institutions of learning are no exception. Most workers in the institutions of learning are willing to work when the leadership creates an avenue for their involvement and if possible, advise during decision making. In addition, these workers always give their best when the leadership/management team are concerned about their welfare especially at times when they are passing through difficult times. This contributes to employee’s performance to some extent. The type of leadership style (either concerns for work or concern for staff) determines to an extent the level of achievement of such higher institution. In addition, most institutions of learning heads are still not in good accord in terms of person relationship and even in administrative works despite huge amount investments on leadership training by the Government to keep them abreast of the new trends in administrative skills.

In Ahmodu Bello University, Zaria the employee has great freedom thus enabling the individual to participation and in self determination to produce positive results through satisfaction. However, leaders, only concentrated on maintaining a steady state of affairs, and only intervened when the followers deviated from expectations. Students’ satisfaction is a complex concept consisting of several dimensions (Marzo-Navarro et al., 2005; Richardson, 2005). Students’ satisfaction in higher education is influenced by a number of variables. Several past studies show that there were related factors influencing students’ satisfaction namely the quality of courses (Arif et al., 2013; Wilkins & Balakrishnan, 2013), effectiveness of instructional process (Bunjak et al., 2019; Helgesen & Nesset, 2007; Elliot & Healy, 2001), course organization (Navarro, Iglesias & Torres, 2005), interaction with students (O'Driscoll, 2012), the focus on student’s needs (Elliot & Healy, 2001) and campus climate (Sojkin et al., 2012).

The extent to which leadership of institutions facilitate the process of change and change management to ensure survival and achievement during their tenure has called for a great concern. Sackmann et al. (2009) opine that lack of adequate skills, knowledge, experience and capabilities in top level managers facing change contribute to poor performance of organizations and government in a competitive environment. Too little attention is given to the consequences of leaders developing a vision that is not fit for its purpose. Some leaders of higher institutions in Nigeria are not sensitive to the opportunities and constraints facing their staff and students thereby denying followers desired satisfactions derivable from good leadership particularly in times of rapid change as we have it today.

Douglas McGregor propounded the Theory X and Y of motivation to explain that there are two categories of followers in every organization which leaders must pay close attention to. The first category which McGregor refer to as “X” are those who try to avoid responsibility and change within the organization unless they are coerced. A leader in this situation will naturally exhibit an autocratic style to ensure that his followers key into the change. The second category of followers are those who are naturally enthusiastic about their job and will support new developments in the organization. Leaders in this situation are expected to adopt a democratic or laissez-faire leadership style. Change is paramount in every aspect of life and more importantly, the education sector of Nigeria, which is long overdue to go through the phases of change as experienced in advanced nations of the world. To this end, the research work tends to investigate how change leadership affects or influences followers’ satisfaction in tertiary institutions in South West Nigeria.

Research Methodology

The research work makes use of cross-sectional survey using administered questionnaire. Interviews were conducted to collect the primary data. The questionnaire used for the research work was divided into four sections which are; leadership concern for work, leadership concern for staff, leadership concern for staff and work and the last section deals with followership satisfaction. However, the dependent variable was followership satisfaction whereas the independent variables were; leadership concern for work, leadership concern for staff and leadership concern for work and staff. The questionnaire was in two pages with the constructs for leadership concern for work, leadership concern for staff, leadership concern for work and staff and followership satisfaction were all measured at four-point scale (1: Strongly Disagree (SD) to 4: Strongly Agree (SA)). The questionnaire was prepared in English language. Only 1497 copies of questionnaires were retrieved out of 1600 copies distributed among staff of selected higher institutions of learning in Nigeria which resulted in 93.5% return rate. In addition, the survey was conducted in 2019.

Hypotheses of the study

In order to test the relationship between the dependent and the independent variables, the following hypotheses were developed:

H1: Leadership concern for work does not significantly affect followership satisfaction in Nigeria.

H2: Leadership concern for staff does not significantly affect followership satisfaction in Nigeria.

H3: Leadership concern for work and staff do not significantly affect followership satisfaction in Nigeria.

Data Analysis

Cronbach’s alpha was performed to examine the internal consistency of the study scale and the result is as presented in Table 1. The Cronbach’s alpha values are 0.784 for concern for work, 0.722 for concern for staff, 0.753 for concern for work and staff, 0.794 for followership satisfaction. Nunnally (1978), affirmed that a score above 0.7 is considered reliable, hence all the scales of this research are reliable and acceptable.

| Table 1 Summary of the Reliability Test | ||

| Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha | No of items |

| Leadership concern for work | 0.784 | 5 |

| Leadership concern for staff | 0.722 | 5 |

| Leadership concern for work and staff | 0.753 | 5 |

| Followership satisfaction | 0.794 | 6 |

Also, various descriptive statistics like frequencies, means, and standard deviations were used to describe the responses of the respondents to each of the items contained in the questionnaire. Furthermore, Pearson Product-moment correlation was used to investigate the strength and the direction of the relationships in the hypotheses. Multiple regression analysis was used to ascertain the effect of the respective independent variables (leadership concern for work, leadership concern for staff and leadership concern for work and staff) on the dependent variable (followership satisfaction).

The demographic information of the respondents as presented in Table 2 shows that majority of the respondents were female. In addition, respondents that were above 56 years of age dominate the respondents that were used for the research work, followed by those respondents within age group of 31 – 43 years of age making up 27.8% of the respondents. Furthermore, 80.2% of the respondents were married followed by 16.8% of the respondents which were single. 73.3% of the respondents were academic in their respective institutions and the remaining were non-academic staff. However, 27.5% of the respondents were O’level holders with most of the respondents having MSc. /MBA in their respective areas of specialization and only 10% of the respondents were PhD holders.

| Table 2 Demographic Information of the Respondents | ||||

| S/N | Statement | Responses | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| 1. | Gender | Male | 659 | 44.0 |

| Female | 838 | 56.0 | ||

| 2. | Age | 18-30 years | 229 | 15.3 |

| 31-43 years | 416 | 27.8 | ||

| 44-56 years | 308 | 20.6 | ||

| Above 56 years | 544 | 36.3 | ||

| 3. | Marital status | Married | 1200 | 80.2 |

| Single | 251 | 16.8 | ||

| Divorced | 46 | 3.1 | ||

| 4. | Job status | Academic staff | 1098 | 73.3 |

| Non- Academic staff | 399 | 26.7 | ||

| 5. | Qualification | SSCE/HND | 412 | 27.5 |

| HND/B.Sc. | 370 | 24.7 | ||

| M.Sc./MBA | 566 | 37.8 | ||

| PhD | 149 | 10.0 | ||

Descriptive Analysis of the Responses

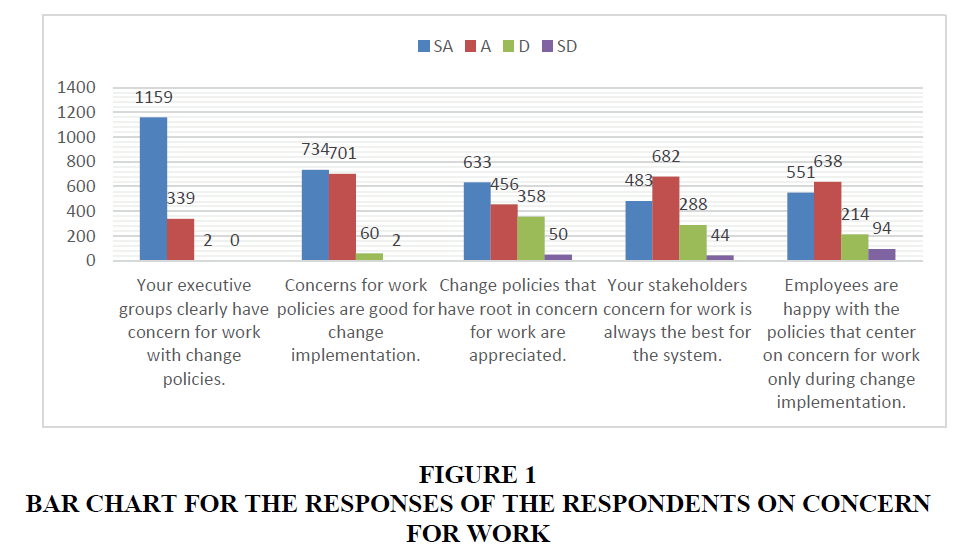

Figure 1, shows the responses of the employees (academic and non-academic) of the institutions used for the research work. The table above shows the responses of the respondents on leadership concern for work in their institution. It was observed that 77.4% of the respondents strongly agreed with the statement that their executive groups clearly have concern for work with change policies and 22.4% of the respondents agreed with the statement. Also, 49% of the respondents strongly agreed with the statement that concerns for work policies are good for change implementation and 46.8% of the respondents agreed with the statement, which is an indication that work policies are necessary for the new leaders for them to be able to achieve their vision for the institution.

In addition, of the respondents 42.3% strongly agreed that change policies that have root in concern for work are appreciated and 30.5% of the respondents agreed with the statement. 32.3% and 45.6% of the respondents strongly agreed and agreed with the statement that their stakeholders concern or work is always the best for their system. The reason could be as a result of the attitude of most staff to work especially when they are not being monitored by the superior officer. More also, it is believed that institutions of learning is a place where characters are mold and hence there is need to showcase good examples for the upcoming young staff and most especially students in the institutions of higher learning.

Lastly, 36.8% of the respondents strongly agreed with the statement that their employees are happy with the policies that centre on concern for work only during change implementation, 42.6% of the respondents agreed with the statement and 14.3% disagreed with the statement. In general, the average response to the constructs on leadership concern for work during change period stands at 3.30 which is an indication that the responses are in favour of leadership concern for work. The result is a signal that most leaders of the higher institutions used are most interested in the way works are being done and the standard deviation (Std. dev. = 0.711) of the responses shows that there is no much variation in the opinions of the respondents.

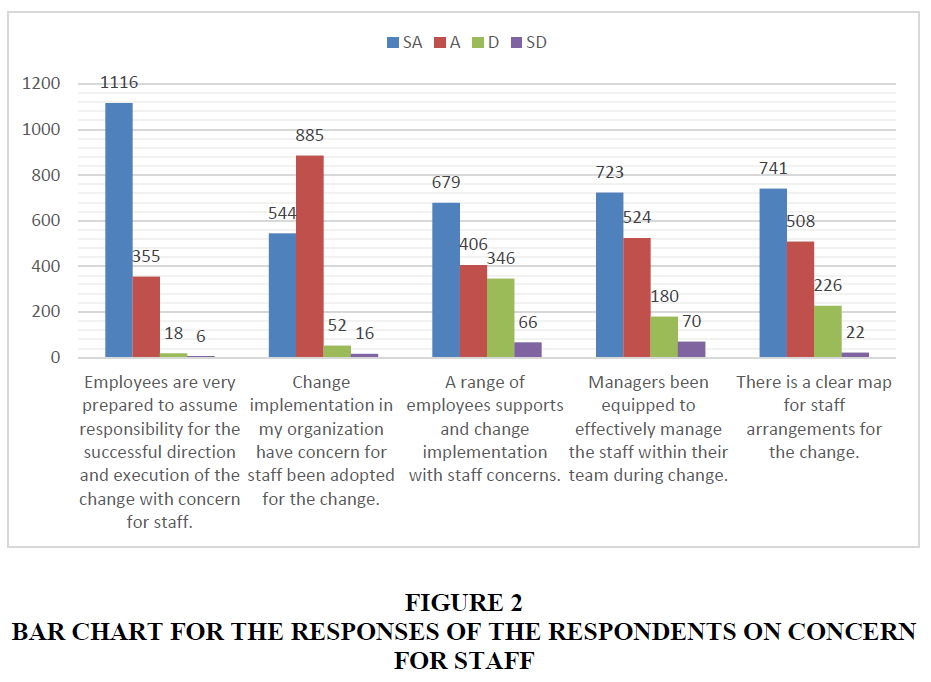

From Figure 2, 74.5% of the respondents strongly agreed that they are prepared to assume responsibility for the successful direction and execution of the change with concern for staff and 23.7% of the staff also agreed with the statement. This implies that for an effective implementation of change in the institutions, the welfare of the staff should not be jettisoned because they are human beings that also have some other responsibility to take care of within or outside the family circle. The society is a circle that believed in give and take and someone should not assume that the staff will give it all for work without their welfare. Over 95% of the respondents were of the opinion that change implementation in their institution have concern for staff in form of welfare packages or other forms of palliatives that will make them part of the organization, in addition, 72.5% of the staff used for the research work affirmed that they supports any change implementation that put into consideration staff welfare. Furthermore, it is believed that the headship of any institution is not the only one involved in the change implementation. In fact, change implementation involved sub-heads (like the Deans, Head of Departments, Directors etc), hence all of them must be part of the change chain for adequate and full implementation of change. 83.3% of the respondents confirmed that these headships were well equipped to effectively manage the staff for full implementation of change policies. The average response of the respondents is 3.31 which indicates that majority of the institution’s leadership have concern for staff and the standard deviation of the responses stands at 0.726 showing no much variation in the responses of the respondents.

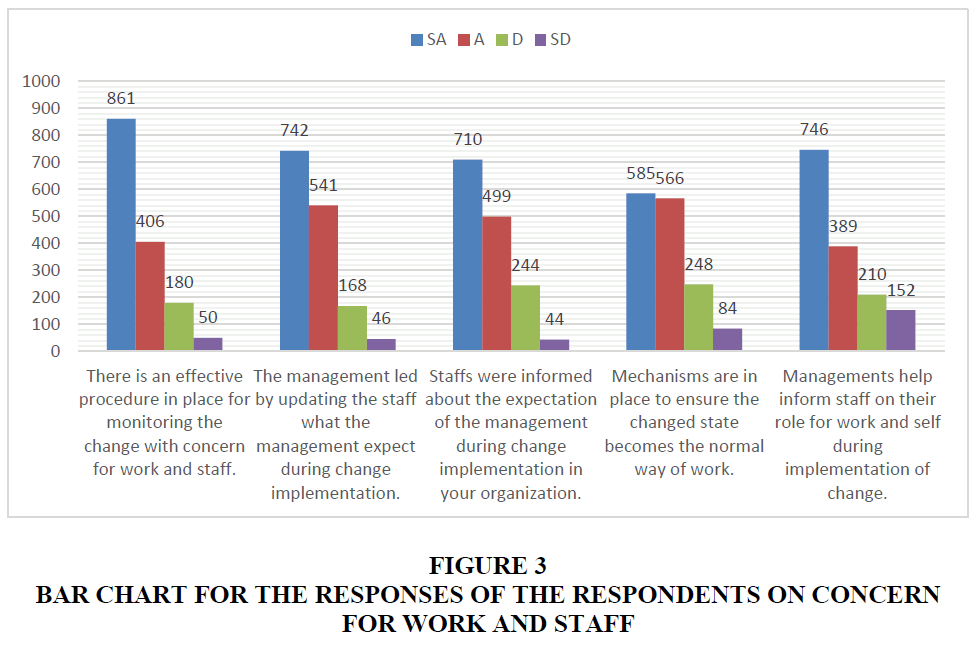

It is a general belief that organizations/institutions could be managed in such a way that the management will not be skewed toward one side than the other in terms of concern of the management for work and their interest towards the staff. Figure 3 below shows that 84.6% of the staff used for the research work affirmed that there are effective procedures put in place in their institutions to monitor the change implementation policies such that work and staff welfare will not be jeopardize. It is a general believe that such policy implementation strategy that have concern for work and staff will aid in good output (staff performance). More also, 49.6% of the respondents strongly agreed with the statement that the management always update them on what the staff were expected to do during change implementation period and 36.1% of the staff also agreed with the statement. By this, this is evidence that there is enough awareness on what the staff should do during change process.

Also, 39.1% of the respondents strongly agreed that there is mechanism in place for sustaining the change policies such that it becomes a normal daily activity in the organization for long, also, 37.8% of the respondents agreed with the statement. Similarly, 75.8% of the respondents confirmed that there is adequate information to the staff by the management on the staff role during implementation of change in the institutions, because this will be the driving force for the sustenance of the change policies. The responses are also in favour of the statements in the questionnaire and there is no much variation in the responses with the average response of 3.24 and standard deviation of 0.868.

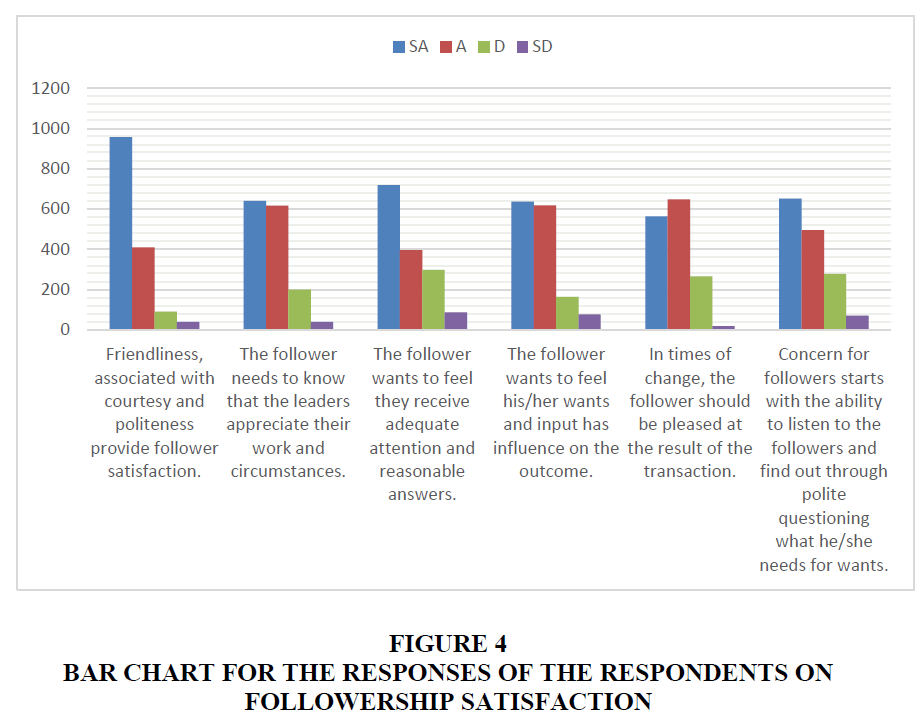

Followership is the other side of leadership and it is a direct concept which implies the ability to take direction well, to get in line behind a program, to be part of a team and to deliver on what is expected of someone. It could be defined as the willingness to corporate in working toward the accomplishment of defined goals while demonstrating a high degree of interactive teamwork. Followership satisfaction refers to a situation whereby a follower has reached a high level of comfort, willingness and a rare passion for a given assignment and such assignment accomplished the set standard without any supervision. From Figure 4, 91.3% of the staff were of the opinion that friendliness, associated with courtesy and politeness provide followers satisfaction and hence helps them to implement change policies without much rancor. In addition, leaders are expected to give followers (staff) sense of belonging and also appreciate their little effort and they should also share their circumstances no matter what. 48% and 26.4% of the respondents strongly agreed and agreed that the followers want adequate attention and reasonable answers whenever needed by the leadership of the organization.

In addition, 42.5% strongly agreed that followers want to feel his/her input has influence the outcome of the organization and 41.3% of the respondents agreed with the statement. It is very important for the leadership of the institution to appreciate and motivate followers in order to achieve more by informing them the new feet achieved and the possibly the efforts of the followers that had contributed to this achievement. This will definitely spur the followers to do more. However, 37.7% and 43.2% of the respondents strongly agreed and agreed that the followers must be satisfied/pleased at the result of the change implementation, else this will result in a situation whereby the followers may tends to retract their support for the new policies.

Furthermore, 43.5% of the respondents strongly agreed with the statement that concern for followers start with the ability to listen to the followers and find out through polite questioning what he/she needs or wants. This will definitely make the followers to have a sense of belonging and thereby makes him feel like being one of the initiators of change policies, and lastly, 33.1% of the respondents also agreed with the statement. However, the average response is 3.24 which is in favour of followership satisfaction and there is moderate variation in the responses of the respondents with the standard deviations of 0.822.

Relationship between the Variables

On the result of the Pearson’s product moment correlation as obtained in Table 3, there is statistically significant positive and strong relationship between concern for work and followership satisfaction (r = 0.620, p=0.000). This suggest that policies that are more work focus have significant relationship with the followers (academic and non-academic staff) satisfaction in various institutions of learning. In addition, there exists strong positive relationship between concern for staff by the leaders of the institutions of learning and followers’ satisfaction (r = 0.708, p=0.000). By implication, it is observed that leadership policies that are more staff centered will spur the followers to feel more concern about their work and thereby the followers which tends to give room for job satisfaction and performance. Lastly, there exists strong positive relationship between concern for work and staff and followers satisfaction in the respective institutions of learning (r = 0.762, p = 0.000). The result revealed in as much there are policies that take care of work and staff, followers (staff) tends to be more satisfied with their jobs than ever.

| Table 3 Pearson-Product Moment Correlation | ||||

| Concern for Work (CW) | Concern for Staff (CS) | Concern for work and Staff (CWS) | Followership satisfaction (FS) | |

| Concern for Work (CW) | 1 | |||

| Concern for Staff (CS) | 0.628** | 1 | ||

| Concern for work and staff (CWS) | 0.682** | 0.776** | 1 | |

| Followership satisfaction (FS) | 0.620** | 0.708** | 0.762** | 1 |

The research work shows that the different age groups (Table 4) responded differently to the statement contained in the questionnaire in respect of leadership concern for work, leadership concern for staff and leadership concern for both work and staff in policy making and implementation in the institutions of learning in Nigeria. As indicated in Table 4, the F-value for the test on concern for work is 125.406 and p-value < 0.05 significant level. In the same vein, similar results were obtained for their responses on leadership of the institutions concern for staff and leadership concern for staff and work combined.

| Table 4 Anova for the Responses of the Respondents with Respect to Age | ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| CW | Between Groups | 2165.702 | 3 | 721.901 | 125.406 | 0.000** |

| Within Groups | 8594.475 | 1493 | 5.757 | |||

| Total | 10760.176 | 1496 | ||||

| CS | Between Groups | 1001.438 | 3 | 333.813 | 56.721 | 0.000** |

| Within Groups | 8786.606 | 1493 | 5.885 | |||

| Total | 9788.044 | 1496 | ||||

| CWS | Between Groups | 2196.763 | 3 | 732.254 | 90.443 | 0.000** |

| Within Groups | 11974.476 | 1479 | 8.096 | |||

| Total | 14171.239 | 1482 | ||||

It was observed that the opinion of the staff of the institutions of learning on concern for workers in age group 18 – 30 years is different from those within 31 – 43 years of age but similar to those within 44 – 56 years and those above 56 years of age. In addition, on concern of the leaders of the institutions for staff, respondents within ages 18 – 30 years have similar opinions on leadership policies toward the staff with ages above 56 years and those with ages above 56 years have similar opinion with those with ages 44 – 56 years of age. Lastly, on the leadership of the institutions concern for both work and staff, it was observed that respondents with ages above 56 years have the same opinion of the statements with other age groups.

Furthermore, the opinion of the academic staff of the institutions and non-academic staff of the institutions was examined whether there is similarity in their opinions with respect to leadership of the institutions concern for work, leadership of the institutions concern for staff and leadership of the institutions concern for work and staff combined (Table 5 below). The result revealed that their various responses were the same as the p-values < 0.05 significant level.

| Table 5 Anova for the Responses of the Respondents with Respect to job Status | ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| CW | Between Groups | 1802.507 | 1 | 1802.507 | 300.831 | 0.000** |

| Within Groups | 8957.669 | 1495 | 5.992 | |||

| Total | 10760.176 | 1496 | ||||

| CS | Between Groups | 940.556 | 1 | 940.556 | 158.930 | 0.000** |

| Within Groups | 8847.488 | 1495 | 5.918 | |||

| Total | 9788.044 | 1496 | ||||

| CWS | Between Groups | 2262.349 | 1 | 2262.349 | 281.348 | 0.000** |

| Within Groups | 11908.890 | 1481 | 8.041 | |||

| Total | 14171.239 | 1482 | ||||

Test of Hypotheses

The research work utilizes multiple regression analysis in order to test the various specified hypotheses in the research work using ordinary least square method. The dependent variable for the study was followership satisfaction (FS) and the independent variables are; leadership of the institutions concern for work (CW), leadership concern of the institutions concern for staff (CS) and leadership of the institutions concern for work and staff (CWS) combined.

The summary table presented in Table 6 shows that there is a strong positive relationship between the joint effect of the independent variables and the dependent variable with R= 0.789. It was observed that about 62.3% variation in followers (academic and non-academic) satisfaction could be attributed to the joint effect of the independent variables with adjusted R-squared value of 0.622. The standard error of the estimate was 2.12869 and the Durbin Watson was 2.311.

| Table 6 Summary of the Multiple Regression Result | |||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | 0.789a | 0.623 | 0.622 | 2.12869 | 2.311 |

The F-value for the ANOVA as indicated in Table 7 is 815.268 with p-value < 0.05 significant level which is an indication that the model is adequate and sufficient in relating leadership of the institutions concern for work, staff, work/staff combined and followers (academic and non-academic staff) satisfaction.

| Table 7 Anova for the Multiple Regression | ||||||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | 11082.705 | 3 | 3694.235 | 815.268 | 0.000** |

| Residual | 6701.811 | 1479 | 4.531 | |||

| Total | 17784.517 | 1482 | ||||

The result presented in Table 8 indicated that in the absence of the leadership of the institutions concern for work, leadership concerns for staff, and leadership concern for staff and work combined, the intercept was 2.186, suggesting that followership (academic and non-academic staff) satisfaction is positive and it was significant. However, in the absence of institutions leaders concern for staff and leadership of the institutions concern for work and staff combined the regression coefficient for leadership of the institutions concern for work was 0.180 with standard error of 0.029 and the t-value was 6.256. More also, the regression coefficient for concern for staff was 0.343 with standard error of 0.035 and t-valued of 9.800. Lastly, the regression coefficient for concern for work and staff combined in Table 8 was 0.526 with standard error of 0.031 and t-value of 17.018.

| Table 8 Coefficient Table for the Contribution of Each Independent Variables | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 2.186 | 0.396 | 5.526 | 0.000 | |

| CW | 0.180 | 0.029 | 0.140 | 6.256 | 0.000 | |

| CS | 0.343 | 0.035 | 0.254 | 9.800 | 0.000 | |

| CWS | 0.526 | 0.031 | 0.469 | 17.018 | 0.000 | |

The respective p-values < 0.05 which is an indication that the independent variables are significant and hence the alternative hypotheses were accepted. We can then conclude that leadership of the institutions concern for staff, concern for work and concern for work/staff combined have significant effect on followership satisfaction.

Discussion of Findings

The study established that leadership of tertiary institutions policy style (either concern for work, concern for staff and concern for work and staff combined) have significant impact on followers’ satisfaction motivation. There is a very strong relationship between the policy choice and the way the followers tend to do their respective jobs be it academic or non-academic staff and even the newly employed staff. However, leadership of the higher institutions of learning concern for work and staff seems to more influence on the followers’ satisfaction compared to leadership interest on work or staff separately. In the various higher institutions of learning, staff (academic or non-academic) even young and old staff tends to provide more work quality and show high level of commitment to various assignment given to them whenever the policy in place is not all about work alone. A leader with more passion for work and staff welfare in higher institutions of learning will find it easier for him to control and achieve its major goals which will definitely makes him/her to achieve more during his/her tenure in office. This result is in line with the findings of of (Arendt et al., 2019; Norazilawani & Hanum, 2018; Naiemah & Abdulsatar, 2018; Jin et al., 2016).

The outcome of the finding is in line with the theory that followers will be more satisfied with their organization during change when the leadership of the organization put policies that have concern for work and staff in place. This implies that followers (Staff) will welcome change policies put in place by the organization provided their welfare is considered. In this regard, government has a role to play in ensuring that employees’ welfare are met by organization. The government of Nigeria should review existing labour laws to improve on any grey areas, thereby ensuring that employees’ welfare are adequately taken care of by organizations.

Furthermore, the study revealed that during change implementation, higher institution policies that tends to favour staff (academic and non-academic) leads to positive and significant effect on followership satisfaction. This is in line with (Oreg & Berson, 2019; Hinic et al., 2018; Olga et al., 2016). However, policies implemented during change that favours only work in the higher institutions of learning though tends to have positive and significant impact on followers’ (academic and non-academic staff) satisfaction but the impact is not much compared to impact felt by policies with concern for staff.

Lastly, balanced policies with concern for work and staff combined in higher institutions of learning has more significant positive impact on followers’ (academic and non-academic staff) satisfaction, which is in line with the independent researches of (Suryanto et al., 2019; Bunjak et al., 2019; Orthodoxia et al., 2019). In general, it was observed that change policies that have Staff and work policies combined tends to have much impact on followership satisfaction in higher institutions of learning in Nigeria.

Conclusion

Change leadership in higher institutions of learning Styles in Nigeria is known and practiced in all higher institutions of learning whenever the tenure (eight years maximum) of an administrator expires so that another leader will be selected to lead the affairs of the institution. Each new leader comes up with his/her own policies which will drive the affairs of the institution of learning all through. However, these goals and visions were integral part of what will form the policies to be put in place for smooth running of the new admiration. It is observed that most leaders of the higher institutions of learning in Nigeria are always with policies that does not favour the followers (academic and non-academic staff) which in turns resulted in strike actions and unstable academic calendar. Therefore, it is suggested that leaders of the higher institutions of learning should be careful in their policies choice and come up with balanced policies that favours both staff and work which it is believed will lead to high followers (academic and non-academic staff) satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) for sponsoring this research. In addition, we acknowledge the management and the research committee of the Federal Polytechnic Ilaro, Ogun State, Nigeria for their support for during the research work. Lastly, we appreciate the staff and managements of various institutions used for the research work and our reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

- Arendt, J.F.W., Verdorfer, A.P. & Kugler, K.G. (2019). Mindfulness and leadership: communication as a behavioral correlate of leader mindfulness and its effect on follower satisfaction. Front Psychology, 10, 667.

- Arif, S., Ilyas, M., & Hameed, A. (2013). Student satisfaction and impact of leadership in private universities. The TQM Journal, 25(4), 399-416.

- Bunjak, A., Černe, M. & Wong, S.I. (2019). Leader–follower pessimism (in) congruence and job satisfaction: The role of followers’ identification with a leader. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40, 381-398.

- Elliot, K.M., & Healy, M.A. (2001). Key factors influencing students’ satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 10(4), 1-12.

- Helgesen, O., & Nesset, E. (2007). What accounts for students’ loyalty? Some field study evidence. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 21(2), 126-143.

- Hinic, D., Grubor, J. & Brulić, L. (2018). Followership styles and job satisfaction in secondary school teachers in Serbia. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 45(3), 503-520.

- Jin, M., McDonald, B., & Park, J. (2016). Followership and job satisfaction in the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 29(3), 218-237.

- Kestetner, J. (1994). “New Teacher Induction. Findings of the Research and Implications for Minority Groups”. Journal of Teacher Education, 45(1), 39-45.

- Locke, E. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In: M. Dunnette(Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pages 1297-1349). Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Lorenzi M.N., & Riley, R.T. (2000). Management change: An overview. Journal of Management, 11(4), 445-450.

- Marzo-Navarro, M.M., Iglesias, M.P., & Torres, M.P.R. (2005). A new management element for universities: satisfaction with the offered courses. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(6), 505-526. ttp://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513540510617454.

- Naiemah, S.U., & Abdulsatar, S. (2018). The influences of job satisfaction and performance on employees followership styles: A survey in the Malaysian Health Institution. International Journal of Engineering and Technology, 7, 842-846.

- Norazilawani, A., & Hanum, H. (2018). Leadership and followership in organizational impact humanity in government sector. MATEC Web of Conferences. 150. 05098.

- O'Driscoll, F. (2012). What matters most: An exploratory multivariate study of satisfaction among first year hotel/hospitality management students. Quality Assurance in Education, 20(3), 237-258.

- Olga, E., Ronit, K., Charalampos, M., & Robert, L. (2016). Leadership and followership identity processes: A multilevel review. The Leadership Quarterly/Yearly Review, 10.

- Oreg, S., & Berson, Y. (2019). Leaders’ impact on organizational change: bridging theoretical and methodological chasms. Academy of Management Annals, 13(1), 45-52.

- Orthodoxia, P., Kourtesopoulou, A. & Kriemadis, A. (2019). The relationship between leadership behaviors and job satisfaction: The case of Athens Municipal Sector, 8, 49-62.

- Richardson, J.T.E. (2005). Instruments for obtaining student feedback: A review of the literature. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 387-415.

- Sackmann, S.A., Eggenhofer – Rehart, P.M., & Friesl, M. (2009). Sustainable change: long – term efforts towards developing a learning organization, The Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 45(4), 521-549.

- Sarker, A.H., Crossman, A., & Chinmetee, P. (2003). The Relationships of Age and Length of Service with Job Satisfaction: An Examination of Hotel Employees in Thailand. Managerial Psychology, 18, 745-758.

- Shawa, J.D., Delerb, J.E., & Abdulia, H.A. (2003). Organisational Commitment and Performance among Guest Workers and Citizens of an Arab Country. Journal of Business Research, 56(2), 1021-1030.

- Sojkin, B., Bartkowiak, P., & Skuza, A. (2012). Determinants of higher education choices and student satisfaction: the case of Poland. High Education, 6(5), 565-581.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9459-2.

- Suryanto, E., Syah, T.Y.R., Negoro, D.A., & Pusaka, S. (2019). Transformational leadership style and work life balance: The effect on employee satisfaction through employee engagement. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 91, 310-318.

- Wilkins, S., & Balakrishnan, M.S. (2013). Assessing student satisfaction in transnational higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 27(2), 143-156.