Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 1S

Constitutional Dialogue in Judicial Review at the Indonesian Constitutional Court: The Future Prospects

Ahmad, State University of Gorontalo

Fence M. Wantu, State University of Gorontalo

Dian Ekawaty Ismail, State University of Gorontalo

Citation Information: Ahmad., Wantu, F.M., & Ismail, D.E. (2022). Constitutional dialogue in judicial review at the Indonesian constitutional court: The future prospects. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S1), 1-8

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to formulate a model of constitutional dialogue implementation in judicial review of the 1945 Constitution at the Indonesian Constitutional Court. The writing approach employed the Statute Approach, Conceptual Approach, and Comparative Approach. The novelty of this paper is a model of constitutional dialogue implementation in the judicial review of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia at the Constitutional Court that put emphasis on on decision making through interpretation, which can be done using 2 (two) schemes. The first scheme is an active interpretation that the Constitutional Court and the People's Consultative Assembly jointly carry out on judicial review related to the Constitutional Court in which the decisions are made by converting votes, 60% votes of the Constitutional Court and 40% votes of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR). The second scheme is passive interpretation, in which the Constitutional Court can inquire the People's Consultative Assembly to provide an interpretation of constitutionality on account that the interpretation is limited to the approach of original intent interpretation.

Keywords

Constitutional Dialogue, Interpretation, Judicial Review.

Introduction

Through the constitutional construction contained in the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia (hereinafter referred to as the 1945 Constitution), the Constitutional Court (hereinafter referred to as the Constitutional Court) transforms into a super body state institution. It is applicable that the Constitutional Court with only 9 judges can annul the power of the legislative parliamentary institution, totaling 575 people without being questioned as their decisions are final and binding (Mahfud, 2010). One example is the decision No. 005/PUUIV/ 2006 on judicial review of Law No. 22 of 2004 on the Judicial Commission that is related to the Constitutional Court, in which the Constitutional Court excludes that the term “Judge” is not interpreted as a judge of the Constitutional Court (Maladi, 2010). Furthermore, judicial review of Law no. 7 of 2020 on the Third Amendment of Law no. 24 of 2003 on the Constitutional Court was conducted, a number of NGOs carried out a judicial review of the Law, considering that the Constitutional Court Law what was being reviewed, it raises some questions by NGOs related to the independence of the Constitutional Court in giving decisions, for example, the Constitutional and Democracy NGO (KoDe) (Hidayat, 2020). The subjects highlighted by a number of NGOs are related to the tenure of the judges of the Constitutional Court, and the maximum age of the judges of the Constitutional Court (Detik News, 2020). Thus, from several judicial review related to the Constitutional Court, there was a debate as the Constitutional Court was considered to have violated the principle of which means that none can be a good judge for himself.

Key notes that have also been highlighted, which have influenced the Constitutional Court (MK) journey were the corruption cases that ensnared a number of MK judges, including former Constitutional Court Justices, Akil Mochtar who was involved in the bribery case for the election of Regional Heads (Movanita, 2014), and Patrialis Akbar. It also confirms that the Constitutional Court is the non-faultless state institution, although later the Constitutional Court is a state institution considered to be the custodian of constitutional rights in which the public put high expectation for upholding justice against this institution (Nggilu, 2021).

The problems in the Constitutional Court are inseparable from the institutional deficiencies in the Constitutional Court (Aritonang, 2013). According to the author, in the future the Constitutional Court must build a monitoring system as well as check and balance system in terms of implementing the authority of the Constitutional Court. Specifically dealing with checks and balances system in the process of judicial review for the 1945 Constitution in which it will bring forth a constitutional interpretation by the Constitutional Court, at some point it will be necessary to involve other institutions, particularly in the judicial review related to the Constitutional Court. It should be done in order to maintain professionalism, accountability, and independence of the judges of the Constitutional Court in carrying out their duties.

The author attempts to offer a mechanism for constitutional review in the Constitutional Court with the model of the Constitutional Dialogue in the judicial review to the 1945 Constitution. Conceptually, the Constitutional Dialogue System is a mechanism that can be used as a breakthrough in conflicts of interest that can occur in the Constitutional Court in the judicial review related to it.

The form of implementation of the check and balance system in terms of judicial review to the 1945 Constitution with the concept of Constitutional Dialogue by involving the participation of other institutions in testing norms, the Constitutional Dialogue is a concept of decision making through generalizing perceptions. According to Xavier Groussot postulated that “Dialogue not just a means of communication; it is also a medium of power” (Groussot, 2012). He stated that constitutional dialogue is illustrated as a perfect platform for defending a conflict of interest over a power.

Therefore, strengthening the importance of dialogue process in interpreting the constitution was emphasized by Wulandari that interpretation is not just a method, but actual human knowledge based on observations and human experiences that have existed before and were generated from a dialectical process (Wulandari, 2019). The dialectical space in interpreting the statute constitutionality will further enrich knowledge and provide legitimacy more than just personal institutional recognition.

In a previous article entitled “Indonesian Constitutional Interpretation: Constitutional Court Versus the People's Consultative Assembly”, the interpretation in conducting a Judicial review in the Indonesian Constitutional Court has not been fully clarified until the technical implementation in the judicial review to the 1945 Constitution by involving the MPR in inherently conducting a judicial review also resulted in interpretation. Therefore, in this paper, we will describe the ideal aspect of judicial review in the Indonesian Constitutional Court in the future with the mechanism of constitutional dialogue.

Problem Statement

Based on the background description as conveyed above, the question is what is the ideal future model of judicial review with constitutional dialogue approach at the Indonesian Constitutional Court?

Method

The approach in this paper is the Statue Approach, Conceptual Approach, and Comparative Approach, with primary legal materials, which is authoritative legal materials such as the Constitution, and other laws and regulations, as well as secondary legal materials that are good writings of relevant books and articles. All legal materials are then analyzed prescriptively.

Discussion

Model for Implementation of Constitutional Dialogue in the Judicial Review of the 1945 Constitution at the Constitutional Court

Implementation of constitutional dialogue in the system of judicial review to the 1945 Constitution at the Constitutional Court, it is necessary to formulate its design as a conceptual line from this writing. It is intended to establish a mechanism for testing norms that is not only resilient in terms of the integrity of its decisions, but also as an effort to strengthen the legal basis.

Construction of the Constitutional Dialogue in the judicial review to the 1945 Constitution at the Constitutional Court must pay attention to institutional respect for the People's Consultative Assembly (hereinafter referred to as MPR). Therefore, with the Constitutional Dialogue mechanism, the right to interpret with legally binding is no longer a monopoly of the Constitutional Court, but is distributed to other institutions, which is the MPR.

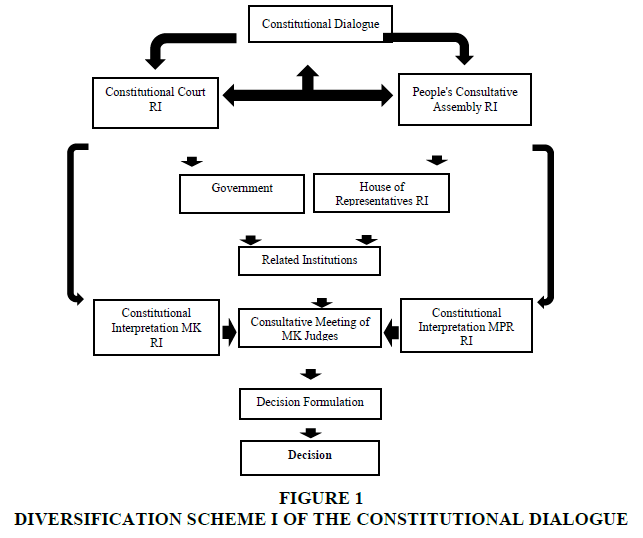

Through this paper, the author formulates a model for judicial review in the Indonesian Constitutional Court by adopting the concept of Constitutional Dialogue into the norms testing in the Constitutional Court that emphasizes decision making through interpretation (Hapsoro, 2020). The following are recommendations for diversification scheme of the constitutional dialogue system into the system for reviewing the 1945 Constitution at the Constitutional Court (Figure 1):

The scheme above is a mechanism for actualizing the concept of constitutional dialogue into the reviewing system at the Constitutional Court. The first scheme that the author offers is to occupy the same position between the MPR and the Constitutional Court in the reviewing room for the constitutional legal products. It is based on consideration of implementation of the authority of each institution (MPR and MK) formulated in a limitative manner in the 1945 Constitution, in which the Constitutional Court conducted the judicial review on the 1945 Constitution, while the MPR limited its authority to amend and make establishment on the results of the amendments to the 1945 Constitution (Ahmad, 2019).

Furthermore, in the first scheme, the presence of the MPR in the reviewing room is mandatory to provide an interpretation of the statute constitutionality related to the Constitutional Court institutionally, which means, if there is a constitutional product reviewed to the Constitutional Court, there is the inherent authority or interest of the Constitutional Court, then the Constitutional Court cannot conceptually interpret the meaning and intent of the norms that are used as a touchstone by the petitioners, so that the interpretation submitted by the MPR must be used by the Constitutional Court in making decision. It is intended so that the resulting decision hold harmless from the shackles and elements of interest from the judges of the Constitutional Court as a judicial institution in which justice seekers put their expectation.

The mechanism as described in the chart above begins with a series of hearings from the parties, which in this case is the petitioners and the appeal and other relevant parties related to the subject matter of the judicial review. In such mechanism, the Constitutional Court and the MPR appear on the same line of interpretation, but the petitioners and the appeal and related parties represent as the parties of which statements will be heard if requested by the Constitutional Court.

The petitioners as referred to above are parties who can become petitioners in the case of judicial review at the Constitutional Court. It emphasizes that the issue of constitutionality cannot be conducted haphazardly based on subjectivity as the constitution is the basic law of the state, so that the determination of legal standing regulated in the Constitutional Court Law is a substantial issue.

Therefore, with this first scheme, it will present a testing mechanism in term of check and balance or conjointly supervise and offset in the implementation of the review authority by the Constitutional Court, especially in terms of decisions in which contain various kinds of interpretation. Therefore, by presenting the MPR RI in the procedural law of judicial review of to the 1945 Constitution in the Constitutional Court, where the interpretation by the People's Consultative Assembly on the judicial review in the first scheme is mandatory in the judicial review, in which the Constitutional Court is institutionally linked.

The referred interpretation will then be set forth in the Constitutional Court decision before being read in the presence of the trial with the agenda of hearing to the reading of verdict. However, prior to that process, in the consultative meeting of judges, the judges of Constitutional Court must include the MPR interpretation as a consideration material without adding to the interpretation. Therefore, it will become a kind of vote conversion in reading the Constitutional Court's decision, although then the Judge of Constitutional Court has the right to give other interpretation outside the MPR. Hence, in order to strengthen the interpretation, it is considered that the MPR votes will be converted into 4 (four) votes.

Determination of 4 (four) votes from the MPR by this author is based on proportionality consideration in which the MPR votes are divided based on a 40:60 scheme, where 60% of the votes of the Constitutional Court and 40% of the votes of the MPR. The MPR vote cannot exceed 40%, as it is done to maintain the independence of the Constitutional Court judges in giving objective decisions. Thus with this scheme, the total votes that will be included in the Constitutional Court's decision to read out are 13 (thirteen) votes.

The conversion model as described by the author above is very helpful in resolving the conflict of interest of the Constitutional Court institutionally. An important note that needs to be underlined in the first scheme is that it will only be applied if there is a review of certain laws, which there is an interest in the Constitutional Court, both institutionally and in terms of function and authority.

Thus, the problem as described by the author in some previous descriptions regarding violations committed by the Constitutional Court institutionally through its decisions that there are a lot of overlapping as it violates several principles in procedural law, one of which is the principle of nemo judex inodeus inpropria causa sua as it is a very important principle. The principles in the procedural law system contained in the judicial system do not solely apply in Indonesia, but also generally throughout the world.

The first scheme as described above is one form of building a more democratic norm testing system by prioritizing the dialogue process in producing constitutional decisions. It is also one of the answers to implement the fourth principle of Pancasila, which mandates a deliberation process to consensus in decision making, especially those are the decisions that have an impact on the general public or the community so that the dialogue process will certainly produce decisions to be accounted for by the community as the holder of the highest sovereignty in this country. It is emphasized in article 1 paragraph (1) the 1945 Constitution ( Siagian, 2021). Therefore, with the dialogue process between the Constitutional Court and the MPR in the process of testing norms in the first scheme is one form of actualizing the conceptual understanding of constitutional dialogue theory in which the process sets down the MPR and the Constitutional Court in the same position to interpret the constitution or the 1945 Constitution.

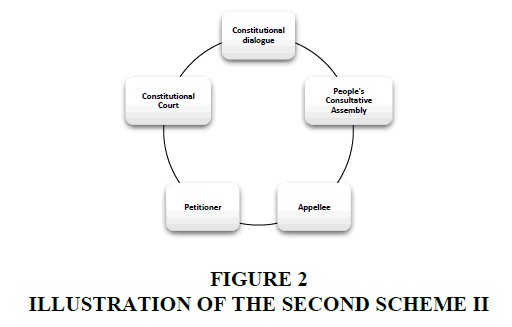

The second scheme offered by the author is that the MPR interpretation mechanism is passive one. In this case the court is able to inquire the MPR to provide space for interpretation of a constitutional product that the Constitutional Court. The referred interpretation is an interpretation based on the constitution or the 1945 Constitution, in the event of the applicant argues that the application is based on the 1945 Constitution, then the MPR is able to provide an interpretation of the meaning, intent, and purpose of the onset of the formulation of the article argued by the petitioners to the Constitutional Court. The following is an illustration of the second scheme (Figure 2):

In this second mechanism, the MPR will use the interpretive approach that is limited to the interpretation approach of original intent or interpretation based on the original intent of the ratio legis and ratio decindendi process of the onset of the formulation of articles and paragraph in the 1945 Constitution. This mechanism will also facilitate the Constitutional Court in formulating the decision as it will be assisted by the presence of the MPR in providing explanation of the norms postulated by the applicants in the examination room at the Constitutional Court.

Constitutional dialogue in this scheme occupies a good position in providing space for democratic decision-making process through dialogue approach as a way of solving problems in terms of resolving constitutional rights issues, which all stakeholders in this country are obligatory to fulfill, especially to the Constitutional Court as the leading sector for the resolution of constitutional aspects that will be debated before the trial of the panel of constitutional judges. Meanwhile, the position of the MPR is significant to open a space for sacralization of interpretation, which the Constitutional Court has carried out as the only legally binding state institution that has the right to interpret the constitution.

An important emphasis that must be paid attention in this scheme is that the MPR position is inactive, meaning that it is the interpretation of the norms of the 1945 Constitution, which is postulated by the petitioners that the MPR will then provide information in the form of interpretation, especially the original intent interpretation approach. Therefore in the trial, there will be a special agenda of which the judges of the Constitutional Court make schedule to hear information from the MPR regarding the norms postulated by the petitioners, so that the existence of this special court room will bring forth a constitutional dialogue between the Constitutional Court and the MPR to explore the goals and objectives to achieve in the Constitutional Court in formulation of articles and paragraphs in the 1945 Constitution. In its theoretical conception, the constitutional dialogue then bring forth to a constitutional dialogue mechanism, which is a dialogue between the judiciary and representative institutions, in this case is a dialogue between the Constitutional Court and the People's Consultative Assembly to produce constitutional decisions, which risked many interests of the Indonesian people.

Thus in this second scheme, the correlation between the Constitutional Court (MK) and the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) in the reviewing room will bring forth interpretations, which will eventually be set forth in the Constitutional Court's decision that will have binding power to all parties, especially to state institutions that will carry out the decision due to the nature of the Constitutional Court decision is final and binding.

Therefore, from the 2 (two) schemes as described above by the author, the author offers to use both schemes in the judicial review of the 1945 Constitution at the Indonesian Constitutional Court, in the event that the laws being reviewed is those related to the Constitutional Court, then the First Scheme is used. Meanwhile, if the laws being tested are not related to the Constitutional Court, then the second scheme is used.

Conclusion

The model of Constitutional Dialogue Implementation in Judicial Review of the 1945 Constitution in the Constitutional Court must position the MPR and the Constitutional Court in the same degree to provide an interpretation of the 1945 Constitution. In order to extend across such similarity of positions, the author offers 2 (two) mechanisms, which are the Active mechanism and the Passive mechanism in conducting constitutionality review. The active mechanism will be used if there is a judicial review related to the Constitutional Court in which 40% of the votes will be converted from the MPR and 60% from the Constitutional Court, while the passive mechanism is the mechanism used when judicial review that is not related to the Constitutional Court. Therefore, the author recommends using those two schemes or in other words, based on what statute the Constitutional Court proposes for judicial review.

References

Ahmad, N.M. (2019). The pulse of the fifth amendment of the 1945 constitution through the involvement of the constitutional court as the guardian principle of the constitution. Constitutional Journal, 16(4), 786-808.

Aritonang, D.M. (2013). The role and problems of the constitutional court in carrying out its functions and authorities. Journal of Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 375-392.

Detik News. (2020). There is a barter behind the ratification of the constitutional court law?

Hapsoro, F.L. (2020). Interpretation of the constitution in the examination of constitutionalities to realize the living constitution. Jambura Law Review, 2(2), 139-160.

Hidayat, R. (2020). The review of the latest constitutional court law will be a test for constitutional justices.

Mahfud, M. (2010). Post-constitutional constitutional law debate. Jakarta: Raja Grafindo Persada.

Maladi, Y. (2010). Benturan asas no suitable judge in proper cause dan asas knows the court's right. Journal Konstitusi, 11(3), 001-018.

Movanita, A.N. (2014). Bribery case for handling akil mochtar pilkada dispute.

Nggilu, N.M. (2021). Legal protection bonda and bulango languange: In reality and prospect. Jambura Law Review, 3(1), 19-36.

Siagian, A.H. (2021). Omnibus law in the perspective of constitutionality and legal politics. Jambura Law Review, 3(1), 93-111.

Wulandari, W. (2019). The authority of the constitutional court in conducting judicial reviews of criminal laws that result in changes in norms in material criminal law judging from the principle of legality. Jakarta: Center for research and case studies, and library management for the registrar and secretary general of the constitutional court.