Research Article: 2025 Vol: 24 Issue: 4

Crisis and Rupture in the Organizational Environment and the Transformations Caused in the Institution of Work

Henrique Adriano de Sousa, Federal University of Parana

Citation Information:de Sousa, H.A. (2025). Crisis and rupture in the organizational environment and the transformations caused in the institution of work. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 24(2), 1-19.

Abstract

Purpose: This investigation, thus, aims to understand institutional change from in person work to home office, triggered by an exogenous shock caused by a moment of crisis in a health insurance company.

Methodology: A qualitative interpretive study was carried out, through a single case study. Data were collected through interviews, observations and documents. Content analysis was used to analyze the data.

Findings: The results showed that, due to a ceremonial domain, in which culture is rooted, it is noted that there was a delay in technological advancement. The change was recognized on three fronts, recognition by the employee, the organization and as a good market practice. The occurrence of a progressive institutional change is highlighted, in which there was the insertion of new technological tools that made it possible to carry out the same activities in a remote, objective and satisfactory way, characterizing the increase in the dominance of instrumental values in relation to ceremonial values.

Originality: The research is original as it shows that ceremonial values continue to coexist in the organization's culture, maintaining the hybrid work model. The study advances theoretically by pointing out that exogenous shocks that shake the environment in which the work institution is inserted, lead to radical changes. Contributing to the demystification of the use of technological tools, leading to an advance in the business context and in the dynamics of work.

Keywords

Exogenous shocks, Work, Institutional change, Instrumental, Ceremonial.

Introduction

Institutional change analyzed through Old Institutional Economics (OIE), highlights the transformations and pressures directed at the structure of values that shape subjects’ behavior. It comprises ceremonial and instrumental values (Bush, 1987; Almeida & Pessali, 2017), both in the institutional arrangement but mutually incompatible. Ceremonial values direct behavior in institutions and organizations, and shape status, privilege, and hierarchical relations, ensuring the structure’s power. On the other hand, instrumental values are related to process efficiency and are directly linked to technology (Pessali, 2017, Bock & Almeida, 2018). The structure of these interacting values in organizations influences the institution of work within them.

Work is seen as an institution, as its relations, regulations, and changes have built history (Freitas et al., 2020). Transformations are latent when we understand work as a routine and an institutionalized organizational practice constructed and shaped over time (Metzger, 2011). This change occurs according to the subjects’ personal and social.development and needs. Change in work settings occurs in two ways: Gradually or radically. The former involves slow adaptations, while the latter happens abruptly, affecting every organization simultaneously (Greenwood & Hinings, 1996). It is worth noting that political factors or abrupt environmental transformations can heighten crises in the institutional system and break the institutions’ stability (Rezende, 2012).

OIE considers the process of change in institutions to be evolutionary, starting from current institutions, and is seen as a continuous procedure that encompasses various events that impact existing relationships (Burns & Scapens, 2000; Scapens, 2006). Additionally, changes in the institution arise from

1. The obsolescence of practices established by traditions, habits, and routines; and

2. Technological changes (Bush, 1983; Rutherford, 1984; Papadopoulos, 2015).

Therefore, discussions around institutional change incorporate the understanding of slow, gradual change- in the natural sense of institutionalization but do not address the impact of exogenous shocks on institutional change.

A recent factor that contributed as an exogenous force to institutional change in Brazil is the labor reform brought about by Law N° 13.467/2017 which presents changes in labor regulation, pondered and discussed over the course of years. This law brought to light the discussion related to telework, a modality in which work is performed outside the company's physical premises, and employees use Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in a way that does not constitute external work (Law No. 13.467/2017). However, to incorporate these changes into the institution of work, employers must go beyond imposing norms, and instead focus on gaining acceptance and instilling new values in the individuals who are part of the organization.

In 2020, the COVID-19 respiratory disease considered an exogenous shock broadly impacted the organizational environment. Organizations have remodeled their strategies to maintain their activities, which has substantially impacted the institution of work. In Brazil, the crisis made 16.6 million workers leave their jobs and begin experiencing remote work (home office) in the initial months (IBGE, 2020). The paradigm shift resulting from COVID- 19 has promoted the adoption of telework by companies.

As the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic lessened, working relationships were reestablished, but some of the administrative work retained home office traits. According to Pacini et al. (2023) industry survey analysts at the Brazilian Institute of Economics of the Getulio Vargas Foundation, the average number of days in home office for workers in the administrative sector has remained stable after the decrease in COVID-19 cases and deaths, and this stability is expected to continue in the future.

Exogenous shocks encourage the transformation of work and permanently alter institutions, resulting in new organizational arrangements and impacting the behavior of individuals in organizations and the ability to change and establish a new reality. Discussions on the institutional change caused by disruptions in the organizational environment that impact the work institution are relevant and intensify debates related to the speed at which adaptations occur- gradually or rapidly. Considering this scenario, we aim to understand the changes in the institution of work directed by exogenous shocks by studying a health insurance carrier.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced companies to operate in a new pattern and dramatically changed the world economic landscape, as well as how organizations and the workplace are viewed. Our study seeks to contribute to theoretical discussions about the institutional change of rapid adaptations involving new economic formats and labor arrangements. Our study provides important information for managers to make their organizations more effective by making better decisions based on the knowledge we offer. Therefore, understanding the sanctioning and recognition of new practices, such as hybrid and home office work, is fundamental to the current scenario.

Our research is limited to the work environment of a health insurance provider a private company in which the characteristics of in person work practices and the adherence to home office are verified. In addition, we analyzed workers who work in administrative services. We identified institutional change through changes in the ceremonial and instrumental values of in person work alongside home office, without expanding the discussions to workers' health and interpersonal contexts.

Materials and Methods

Theoretical Framework

Institutional theory and the change in the work institution: OIE focuses on micro institutions and internal pressures that shape the organization, individual actions and reactions, and management (Scapens, 2006; Ferreira & Rodrigues, 2012). Considering OIE, COVID-19 an exogenous shock tends to shape relationships and how organizations act. This impact results in the activation of technological instruments that provide a new way of doing administrative work and changes in traditional work.

OIE defines institutions as habits of mind, in which actions are reproduced similarly and form a linearity of attitudes that drive how participants in the environment act and relate to each other (Veblen, 1961). Institutions can be seen as the ways they are structured, or the ways they carry out their actions and become rooted in the environment. They shape human conduct and the decision-making process (Veblen, 1961; Cheluchinhak & Cavichiolli, 2010). It is worth pointing out that institutions undergo constant changes resulting from their interaction with the environment and individuals' actions.

Studies about institutional change in Brazil discuss institutionalization emphasizing habits, routines, and rules. OIE approaches institutional change by observing the changes and pressures experienced in the value structure that direct the way the participants of the institutional design act. Bush (1983, 1987) discusses institutional change based on values and differentiates them into ceremonial and instrumental. Ceremonial values are distinguished by individuals to preserve the distribution and army of power in a society. Instrumental value is learned through reinforcement and seeks to apply available knowledge and technology to resolve disputes.

Ceremonial values are related to patterns of judgments that prescribe status, privilege, and hierarchical relationships, reinforcing the use of power among the layers of society (Bush, 1987). They exert force in the direction of actions through repressive, obstructive, and explosive postures that seek to control technology and science, directing greater benefit to the institution that controls the environment (Ayres, 1944; Junker, 1983; Elsner, 2012). Tradition, myth design, and ideologies contribute to the validation of ceremonial values. Consequently, this makes these values perpetual and exerts force towards the execution of actions. As ceremonial values are taken as an authority and absolute truth, they become postulates, and shy away from judgments and criticisms of the individuals participating in the environment (Ayres, 1961; Bush, 1987; Almeida & Pessali, 2017). According to the institutional literature, the set of values prevails and slowly changes over time, including when latent pressures lead to economic inefficiency (Kyriazis et al., 2005). Instrumental values relate to the operational process and are linked to the use of technology (Ayres, 1944; Junker, 1983), which is taken as a purely evolutionary aspect where the inclusion of new technological tools permeates the old ones (Papadopoulos, 2015). It acts as a driver of efficiency, so it gets validated as demands are solved (Tool, 2012; Almeida & Pessali, 2017).

This ceremonial instrumental dichotomous relationship happens close to the institutional fabric, so the thought that ceremonial values are bad and instrumental values are good must be dispelled. The coexistence of values in an institution is important and fundamental since both can produce effects that add to institutions (Almeida & Pessali, 2017). While instrumentalism is directed toward problem-solving, ceremonialism is connected to how things should be done and considers the previously institutionalized aspects. The discussion of change occurs when these predominant values in institutions must be changed. For this, the change in the dominance of values within the institution is essential. For example, ceremonial dominance is noted when ceremonial values override instrumental values in the institution (Lacasa, 2014).

The changes that occur due to the dominance of values can be either progressive or regressive. Regressive change is characterized by an overlap of instrumental values with ceremonial values, which results in a change in the correlation of behavior. On the other hand, progressive change happens from introducing new technologies and knowledge linked to process efficiency. It shifts ceremonially guaranteed behavior patterns to new instrumental values, creating a greater reliance on these values in correlating behavior (Bush, 1983/1987).

According to the OIE, institutions tend to remain stable, that is, resistant to change. Thus, including new behaviors in the institution can be seen as destructive of stability (Burns & Scapens, 2000). Elements of resistance include rejection due to competing interests, cognitive difficulty in change, and divergence of principles. Power, policies, and trust can also influence the change process positively or negatively (Scapens, 2006; Ribeiro & Scapens, 2006; Ferreira & Rodrigues, 2012).

Change processes can be categorized as formal or informal, revolutionary or evolutionary, and progressive or regressive change, according to Burns and Scapens (2000). Formal change comes from the imposition of norms by welcoming new rules that influence the organization. Informal change occurs implicitly and unintentionally and takes effect over time. The two forms can coexist in a change process (Burns & Scapens, 2000; Ferreira & Rodrigues, 2012). Conversely, revolutionary and evolutionary changes are related to the impact on the institution's stability when novelties are implemented in this environment. In the case of revolutionary changes, radical interruptions in routines and, eventually, in institutions are noticeable. In the case of evolutionary changes, conversely, divergence from current routines does not generate substantial impact (Ferreira & Rodrigues, 2012). Burns and Scapens (2000) also link the changing pattern of dominance of ceremonial and instrumental values to progressive and regressive changes.

Institutions are exposed to change, whether fast or slow (Graeff, 2020). This means it is essential to understand that periods considered stable are broken by crises in the institutional system. These crises can be derived from political factors or abrupt transformations. The impacts suffered in the macro environment where the organizations belong- are considered exogenous impacts, which change the form of relationships between the participants of the environment: individuals, institutions, and organizations (Mahoney & Thelen, 2010; Vieira & Gomes, 2014). These impacts lead to the need for internal adaptations, directing strategies, and making institutional arrangements more dynamic.

The changes that occur periodically, where institutional arrangements are renegotiated and altered in form and functions, are considered endogenous (Thelen, 2003). It is essential to understand the negotiations between the agents that participate in the institutional alignment, and visualize the occurrence of an integration agreement to configure institutional change in the endogenous context (Rezende, 2012). This agreement and integration lead to observing the time it takes for the new stability to occur and to be configured as an institutionalized change.

It is important to emphasize the perspective of Lowndes and Roberts (2013), who advance the discussion of institutional change, and discuss the change’s timing and the balance between structure and agency. Aranha and Filgueiras (2016) highlight that time is related to the speed at which the transformation occurs, slower and gradual or fast and abrupt (Aranha et al., 2016). Change and stability are built from the continuous interaction of agents, existing institutional constraints, and the impacts that may be experienced by the institution (Lowndes & Roberts, 2013). To understand this change, it is necessary to consider the dialogue between institutions, agents, and impacts on the environment (Aranha & Filgueiras, 2016).

Introducing new technologies in the in person work environment is a big step towards acquiring knowledge and optimizing processes. This profound transformation in the structures of organizations has been accompanied by the use of remote working methods, such as home office (Dery et al., 2017; Baptista et al., 2020).

The Institution of Work

Work is a constantly changing institution throughout history: Its roots lie in ancient periods of history, when people desired to fulfill their needs. This institution evolved from a slavery system to feudalism and then capitalism which was driven by the first industrial revolution. All subsequent industrial revolutions affected work somehow. The second industrial revolution was characterized by technological advances and reorganization of work with the systematization of industrial activities (Rossato, 2001; Oliveira, 2005; Alvim, 2006). The post-war period, starting in 1945, triggered the third industrial revolution related to science and production, known as the technical scientific informational revolution. This enabled the advancement of new areas such as robotics, genetics, computer science, telecommunications, and electronics (Miranda, 2012). These moments benefited the industrial field, changed work relationships, and enabled the dissemination of control and rapid information, shortening time and distance (Rossato, 2001; Oliveira, 2004; Miranda, 2012). The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) addressed workers' rights in articles XXIII and XXIV.

The milestone in the evolution of work occurs during the fourth industrial revolution, also known as Industry 4.0 (Weking et al., 2020). The world economic forum defines the new revolution as a shift toward the use of resources focusing on the digital revolution. The division between one revolution and another is based on the speed, outreach, and impacts that occur in the systems. This revolution features the digitization and automation of industry through cyber-physical resources and systems and involves the Internet of Things and smart factories. The resources involved also include nanotechnology, neurotechnology, robots, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, 3D printers, and drones.

Cyber-physical work systems are tools with embedded technology capable of monitoring, controlling, and optimizing real-world processes in real time. They combine data collection and analysis with algorithms and computational models, connecting social, cyber, and physical work environments into a single productive, functional entity. The development of this contemporary system allows autonomous decision making, network system cooperation, and communication for advanced management and control (Hozdic & Butala, 2020).

The use of technologies as work tools has increased over the years, especially in the second half of the 21st century (Braz, 2020). There were significant transformations in the way companies are conducted and how they develop their strategies. Work relationships are one of the changing points in the organizational environment.

Contemporary work presents itself differently, which has been gradually built with the advancement and inclusion of new technologies. The old way that sought mass production with less effort and speed, based on Taylorism and Fordism standards, gave way to mechanization and operations that implement digital technologies. Braz (2020) points out that human activity in contemporary work is governed by performance in which the results stand out from the means. This statement agrees with Filgueiras and Antunes (2020) who point out that, currently, many jobs are directed by demand and not by the hour of activity.

In person work has been reformulated with the use of digital technologies. We found office applications, integrated technologies such as cloud storage, mobile technologies, data manipulation, and intelligent sensing technologies. For these technologies to operate, some bases, such as the Internet of Things, intelligent agents, workplace robots, and self-learning algorithms are used (Attaran et al., 2020). Precedents for knowledge and habituation become the basis for profound transformations in the methods and structure of organizations. Therefore, employees start using other work mechanisms, such as home office.

Home Office

Information technology in the organizational environment is considered a "disruptive elementary characteristic of the current times that promotes changes in the way organizations are managed, in the perception of work teams, and facilitates decision making based on information" (Pereira & Monteiro, 2020). ICTs enable access to more robust Management Information Systems (MIS) using control and decision-making mechanisms, such as Business Intelligence (BI) (Lyytinen et al., 2020). Access to digital technologies provides a competitive advantage to organizations and facilitates data collection, storage, access, and analysis. It helps managers control and make decisions, and employees carry out their activities more precisely (Lyytinen et al., 2020; Pereira & Monteiro, 2020).

ICTs present characteristics related to new forms of contemporary work, such as online communication between producers, consumers, workers, and companies; the use of applications or platforms on a computer or mobile communication devices; the use of digital data for the organization and management of these activities; or on-demand relationships (Filgueiras & Antunes, 2020). The use of technological tools enabled new forms of independent and dependent work. Independent work shows itself in the use of digital platforms for digital media production, transportation and delivery services, online sales, or service provision (Howcroft & Bergvall-Kareborn, 2019; Mantymaki et al., 2019). Dependent work is performed in person and remotely, linked to the supervision of a company.

Telework is a dependent, remote work format. It includes home office, a format that consists of performing work at the worker's residence (Rocha & Amador, 2018). In Brazil, Law no. 13.467/2017 assures that telework is performed outside the premises of the affiliated organization, with the aid of ICTs; it is characterized as a flexible form of work based on technological evolutions (Haubrich & Froehlich, 2020). Gajendran and Harrison (2007) define telework as a work arrangement in which employees organize themselves in environments outside the organization. They perform their tasks, have a predefined location, and use ICTs to allow access to data and interact with other individuals inside and outside the organization. Home office provides work practices different from conventional ones, with greater autonomy, flexibility, and opportunities for teleworkers.

Numerous discussions about home office have been raised regarding the impacts of its implementation, such as pressures and concerns for workers, as well as the controls and benefits to the organization (Groen et al., 2018; Pandey et al, 2020). Haubrich and Froehlich (2020) point out that the main benefits for organizations in adopting home office include flexibility, productivity, the possibility of hiring professionals without geographical restrictions, reduced structural and travel expenses, and improved quality of life. Rocha and Amador (2018) highlight its benefits for organizations, such as reduced costs for physical space, equipment, and maintenance, increased productivity, decreased absenteeism, and talent retention. Other studies highlight improved recruitment, selection, and retention of people, and increased productivity (Tavares et al., 2020).

Tavares et al. (2020) corroborate Rocha and Amador’s (2018) findings by pointing out "the flexibility of the working day, the time management to better reconcile social, family, work, and leisure demands, saving time on home-work transportation, and the autonomy to organize the way of working”. Hau and Todescat (2018) include the opportunity to manage time and the best way to perform activities, leading to improved quality of life, job satisfaction, and increased productivity.

The main challenges for organizations are maintaining the organizational culture, contractual model and tackling indiscipline, lack of commitment, difficulties due to the absence of in person contact with the team, and insufficient technologies (Haubrich & Froehlich, 2020). Rocha and Amador (2018) also point to "the difficulty of controlling workers and the loss of their integration and bond with the organization." These two factors have a strong connection concerning the relationship established between the worker and the one who demands the work". With the increase in scams and frauds appropriating private data, security is one of the concerns for companies. Organizations tend to implement massive security measures (Pandey & Pal, 2020).

Pandey and Pal (2020), while verifying the use of digital technologies in telework, pointed out that constant monitoring of the workplace has a negative impact on employees, which increases work stress. The authors also indicated discomfort in learning new technologies, increased workload, use of digital devices more frequently, and multitasking.

A new strategy for controlling workers' activities and schedules such as control by work delivered (activities on demand) is satisfactory in this work mode (Groen et al., 2018; Pandey & Pal, 2020). Adopting home office is different among companies, as they have different motivations, needs, and work styles. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss factors that modify the pre-defined and validated structure during the construction of the institution of work.

Methodological Procedures

Through qualitative, interpretive, and descriptive research (Stake, 2016), we seek to understand the phenomenon of changes in the institution of work from an instrumental case. We selected an organization that met the following requirements:

1. Did not have the telework modality before the shock caused by COVID-19;

2. Had used telework as a strategy for coping with the pandemic;

3. Had the intention to maintain telework or its variations in the business strategy after the decrease of pandemic restrictions; and

4. Had a standardized and well-defined hierarchical structure. Since it met all the requirements, we chose a health insurance carrier.

We built a case study protocol to guide the interviews, observations, and document consultations. We considered the literature regarding behavior patterns linked to the reality of work dynamics, and validated it through a pre-trial, conducted in two stages: Revision by academics, and validation by managers and employees who work in permanent home office.

There were 11 participants interviewed (Eisenhardt, 1989; Godoi & Mattos, 2010) via Zoom. Five interviews were carried out with Managers (M) of the organization who have the team or part of the team in permanent home office, and six interviews with Employees (E) that have switched to home office mode. During the interviews, we looked for evidences of values concerning in person and home office work before and after the exogenous shock. The questionnaire comprised the characteristics of the participants and their professional trajectories; the behavioral structure and work and hierarchical relationships; monitoring of activities; performance; formatting of in person work; and the changes that occurred after the adoption of the home office. We obtained 8 hours and 45 minutes of interviews and 116 pages of transcripts.

In December 2020, we conducted a systematic non-participant observation of three online meetings, which totaled 4 hours and 23 minutes. In January 2021, we conducted a face-to-face observation of an administrative unit, followed by a 2 hour and 15 minutes in person meeting with a manager, where we received documents for the company’s internal use. We collected 11 home office information documents available on the company's communication channels (intranet) and 4 internal documents pertaining to procedures, policies, manuals, and internal research reports. We also analyzed 3 restricted documents: The company's home office corporate policy, the digital document of home office acceptance and adherence, and the contractual addendum of migration to home office.

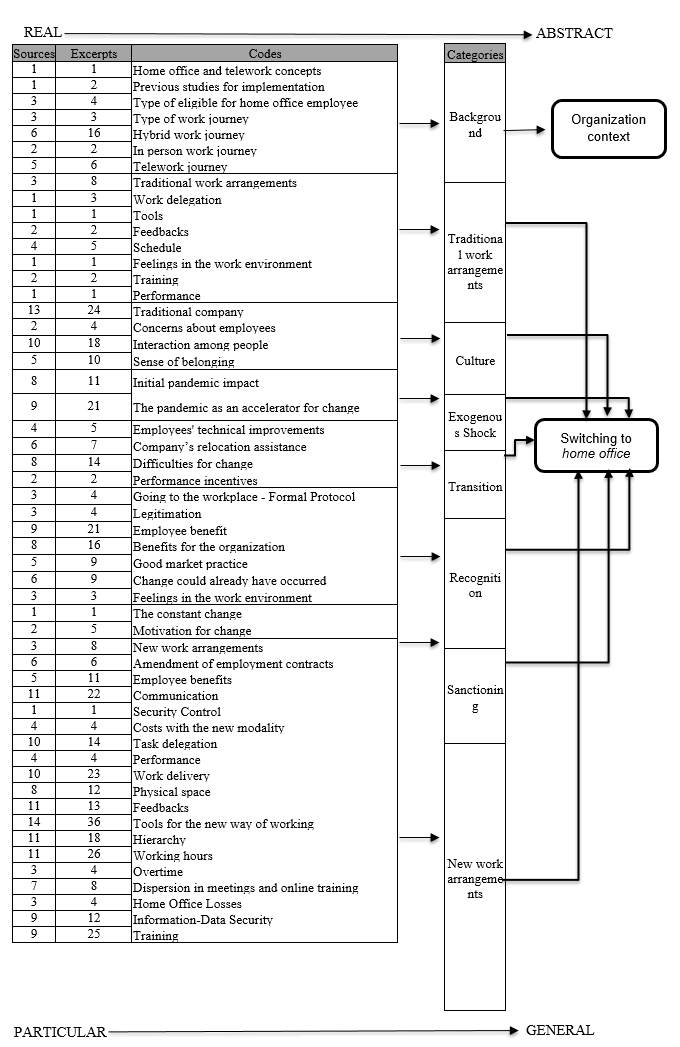

Data processing and analysis were performed using the NVIVO 11 software. We listened to the interviews and the respective transcripts, sorted the observations, and separated the documents at the same time as we collected the data, which was followed by coding, categorization, and content analysis. Content analysis was conducted by interpretivist logic (Stake, 2016; Merriam, 1998). The categories emerged from the analyses of the collected evidence and were systematically grouped into them. After being identified, the excerpts were allocated into codes and grouped into categories to explain the studied phenomenon. Data moves from the real to the abstract (Saldana, 2021), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Data Set

In Figure 1, the source refers to the document from which the excerpts were taken. We coded a total of 496 excerpts and divided them into 53 codes, allocated into eight categories that help explain the change in the institution. We defined the categories as

1. Traditional work arrangements

2. New working arrangements

3. Exogenous shocks

4. Transition

5. Recognition

6. Sanctioning

7. Culture

These categories are further discussed in the following session.

Results and Discussion

Data Description and Analysis

The institution of work in the health insurance company: Private health insurance carriers exist in the form of a civil or commercial company, cooperative, or self-management entity. They provide health services on an ongoing basis, covering clients’ care costs, and are regulated within Brazil by the National Agency for Supplementary Health Services (ANS) (ANS, 2020). The operators systematize health services through partnerships and service agreements, such as the accreditation of clinics and service providers, in order to guarantee access to contractors (Law nº. 9.656/1998).

Supplementary health in Brazil covers 47,058,401 beneficiaries of private health plans through assistance coverage. There are 979 hospital-based medical operators, including dental operators (ANS, 2020). Law 9.656/98 establishes guidelines for private health care plans and insurance, moderate’s agents’ relationships, and mediates possible conflicts of interest.

The supplemental health care environment was affected in several areas by the rise of Covid-19. To protect employees and minimize the disease’s impacts, service provision was modified, and ways of working were changed. The company adopted home office work to cope with the pandemic period. After the restriction measures, remote work was maintained in the administrative functions and a hybrid day regime was adopted: employees began to work in person two days a week and remotely for three days, according to the definitions made by the area manager.

In person work and a fixed routine became representatives of a traditional model. The employee had the responsibility to show up to work, clock in, and comply with the established shift. Timekeeping, pre-set hours, and obedience to routine have become ceremonial behaviors related to work practices (Bush, 1987).

Then the contractual condition changed, as informed by interviewee M1: "[...] we currently have two work contracts, on-site and home, already established within our human resources policy. [...] There is already a contract, [...] more freedom, right, so we have a hybrid contract.

To be eligible, the employees had to meet some criteria: Type of position held; professional profile; and willingness to migrate to the new work modality. The position should be above an operation entry level. The profile evaluated included the use of appropriate equipment and connection and the abilities to concentrate on work; communicate effectively; and adapt to a new environment.

Traditional and new work arrangements: The working arrangements encompass issues regarding the schedule's organization, tool management, training conduction, meetings, technological structure, and location particularities. The interpersonal aspects are related to communication, task delegation, feedback, trust between parties, performance evaluation, and product delivery. The worker’s environmental, organizational, and interpersonal elements relate to each other and are key to understanding change.

We found that, to meet the needs of the various departments and stakeholders of the organization, there is a traditional requirement to meet the hours defined in an employment contract- usually business hours. Despite adopting a remote work model, previous schedules are maintained, as reported by interviewee E6- “[...] I start at the same time I used to start there, I take the same lunch break, I leave at the same time. And when you end up doing overtime, you would have to do overtime in person as well [...]”.

Although not all organizational activities must be performed during business hours, working hours have been standardized to ensure effective communication and labor relations. Ceremonial values continue prevalent as an integral part of the organization's culture and other cultures that transcend organizational barriers. According to Bush (1987) and Pessali (2017), this behavior was maintained as a way to promote work relationships. Even in the new work environments, the values that define schedules remain predominantly ceremonial.

To bring people together while working from home, it was necessary to adopt more modern technological tools. In addition to e-mail, phones, and intranet, the organization now relies on ZOOM Cloud Meetings, Microsoft Office 365, Teams, VPN (Virtual Private Network), and, informally, messaging applications. These tools have made it possible to extend discussions beyond company boundaries and to ease informal communication between employees and managers.

The use of virtual tools for communication has become more and more widespread, as there is no loss of information, making communication more efficient. Studies by Tool and Almeida and Pessali validate this statement, as the authors found that instrumental values act as the efficient cause. The meetings were held with less expenditure of space, time, and travel. The interaction between technological platforms helped to improve the information’s transmission with a greater reach to the public, as highlighted by interviewee E6: "before, it was only in person and now it's by phone, through WhatsApp; we communicate all the time, we talk among the team, with the managers, we have many meetings via Zoom; we are always in touch".

One can see the improvement in communication quality; this confirms Bush (1983), Rutherford (1984), Papadopoulos (2015), and Almeida and Pessali (2017) statements that the inclusion of technologies contributes to change. The institution also underwent change in the value structure, which allowed the acceptance and recognition of this new format (Bush, 1987).

The hierarchy and feedback were quite clear in traditional arrangements. With the home office’s introduction, there was no change in hierarchy or form of feedback, but the management became more present, according to what was reported by interviewee M2: "our hierarchy relationship even became closer! Multiple conversations for people to feel welcomed, to accompany them, to talk about performance, about difficulties, so it went from meetings with small teams up to daily meetings". This behavior is related to using tools and skills to apply knowledge in organizational processes, predominantly characterized by instrumental behavior (Bush, 1987).

Performance in the organization is measured by demand, competence, activities’ delivery, and departmental indicators, which demonstrates instrumental behavior is linked to process efficiency (Pessali, 2017, Böck & Almeida, 2018). During home office, performance evaluations remained the same. This discussion goes back to Almeida and Pessali (2017), who state that the ceremonial-instrumental dichotomy appears and coexists on the surface of organizational structures.

Interviewee E1 reported that there was an innovative direction in the physical space in the organization. This approach led to a reorganization of space and disruption of the sense of belonging to the workplace. The layout was changed to the coworking model, according to the following comment: M1 "so what we are going to do is an internal resizing, we are going to make more modern rooms... we are not going to have fixed positions anymore, except for those who are in the in person work modality,... there will be a shared position".

According to the ceremonial-instrumental dichotomy developed by Pessali (2017), the overall organization had a conservative culture in relation to adopting new technologies. This mentality resulted from an ingrained ceremonial behavior that held back technological progress. On the other hand, the activities, hierarchical relationships, and forms of work demonstrate an instrumental character. It is noticeable that ceremonial and instrumental values coexist in a complex set of relationships regarding work arrangements.

The exogenous shock and change in the institution of work: COVID-19 was an exogenous shock that made companies seek technological means to continue their activities. Telework was a viable solution that allowed people to work remotely using the tools available in the market. This change has had a continuous impact on remote work, something that in other situations would have occurred more slowly and gradually (Rezende, 2012; Aranha & Filgueiras, 2016).

Ceremonial dominance can restrain and delay change because it establishes a value system that does not easily adapt to new technologies. According to Ayres (1944), this hinders instrumental progress by preventing the development of innovations. It is possible to state that it is necessary to overcome this resistance to move forward. The lines of respondent M2 contribute to highlighting this phenomenon: M2 "the questions would be much bigger, we would have to do a pilot project, we would have to test it, so all this would have to happen in a much slower way".

Ceremonial behavior generally takes precedence over instrumental behavior in an institution because of the degree of ideology and culture that are often present (Bush, 1983; Lacasa, 2014). The example cited by E5 shows that management has a certain prejudice against the home office. This interviewee states that "the employee will only work if they are being watched". This means that sometimes instrumental behavior can be dominated by ceremonial values, which can slow down the social development of the institution.

The sanctioning and recognition of the home office: We verified the sanctioning of home office work in the organization through the interviewees' statements and the analysis of the organization's internal documents, which confirmed home office as a definitive modality. These documents included

1. The home office corporate policy, developed to regulate and protect the rights of the parties;

2. The term of free adhesion, which addressed issues such as the effectiveness of home office work, adaptation of the position, interaction with third parties, free adhesion of the employee, and his or her agreement with all items of the policy; and

3. The contractual amendment, which legally materialized the policy, the adhesion term, and the acceptance to change to this modality.

The recognition of the switch to home office was seen as natural and a legitimate type of work. This recognition happened in three main fronts: the benefits for the employees, for the organization, and good market practices. For employees, in addition to discipline, concentration, and performance, remote work brings a quality of life superior to in person work, as pointed out by interviewee E5: E5 "with the money I save I enrolled in other courses, I'm taking another online course that is actually cheaper than what I spent on fuel [...] the convenience of being at home, not stressing because of traffic [...]".

There was a switch in the conservative point of view that employees could not be productive outside the company premises or away from direct management supervision. This contradicted activity delegation and control implemented in traditional work arrangements. After a period of working from home, the results in the departments were maintained and led to committed behavior. Interviewee M3 reported: M3 "We saw that it was really paying off, people were committing, people were really engaged with the process there”. According to manager M2, other results even improved, "working from home has not hurt the business, and in some areas, it was actually the opposite- we’ve had even greater gains”.

Employees were committed to delivering above expectations because they recognize the privileges they have earned. Processes that used to be in person were carried out with dedication and the available tools ensured that the execution happened in an organized manner.

According to the managers who participated in the survey, working from home became legitimate due to the new work formats adopted by multinationals, innovative companies, and others in direct contact with the company. These good business practices are the third front for the recognition of the work change, as reported by M1 "the largest companies, some multinationals, were already working in this format, right, some of our IT suppliers, so it was a business trend [...] and it is also a good business practice".

The year 2020, marked by the pandemic, was heavily impacted by a remote work environment. Opting for the home office model brought better results than previous years, as per external documentation (Doc. 9). The results, monitoring, development, employees’ behavior regarding working from home, and the managers' experience with remote people management contributed to the recognition of this change.

According to Bush (1983/1987), the participants' recognition of home office indicates instrumental efficiency in demands and problem solving. This positive change in the company, employees, management, and the perception of other related parties, such as customers, has contributed to a progressive type of institutional change.

The cultural influence on work change: Organizational culture was key in determining the type and speed of change, and in the acceptance of new routines. Although the triggering factor was an external shock that impacted the entire organization, the orientation of change within it is aligned with its values and culture (Veblen, 1909; Burns & Scapens, 2000).

The organization realized the need to transition values related to work, searching for an innovative model that incorporates technological and social resources and a culture of trust for employees. The cultural pressure for home office to be implemented as the predominant way of working was strong. However, the company opted for a hybrid format, with three days of remote work and two in person, because it recognized that some activities needed to be done in person. This change in values and work format represents a deviation from the culture that has always existed in the organization. It had satisfactory results that differentiated it from other companies in the Brazilian context of home office, where this format was little explored.

The sense of belonging to the organization is an important cultural element for employees. In person contact between people, as pointed out by interviewee E2, is essential to establish this culture. The reasoning for this stems from the need to feel part of the organization, which was recognized by both the company and the employees: E2 "If you manage to create this hybrid structure I think the gain is great on both sides, you can have the convenience of home office, but you don't lose contact with the organization.”

The organization has undergone a gradual transition in its culture from a conservative approach to work into a horizontal and demand-based management. With Covid-19's external shock, the technology factor was included, which allowed this abrupt change in the work format to happen. According to Bush, this resulted in a decrease in the predominance of ceremonial values, which were replaced by instrumental behaviors. The organization's sense of belonging mediated this institutional change.

Change in work as an institution: Having defined work as an institution with rules, practices, and perspectives, change occurs when there is an exogenous rupture in the environment where the institution is inserted. This shock potentially hurts the stability in which work relations take place. According to Lowndes and Roberts (2013), the impact brings to light new ways to use the existing tools and model new practices, and it is a precursor to change in formal rules.

Institutional settings that surround and participate in this institution, such as customers, suppliers, partners, and legal rules that adhere to transformations resulting from the exogenous shock can also shape the behavior of the actors. This intensifies the power of change and adaptation to the new configuration. As Aranha and Filgueiras (2016) show, institutions are dependent on participants for their creation, maintenance, defense, and transformation.

Our research portrays the impact and adaptation of current transformations undergone by work. Unlike other transformations that occurred gradually and slowly, we have shown that adaptation, recognition by the agents, and changes in habits and routines occur quickly and radically. The exogenous shock known as "the Pandemic" is taken as a critical juncture that resulted in radical institutional change (Aranha & Filgueiras, 2016).

These precedents consisted of a robust collection of available but unused technologies, accompanied by ceremonially governed enduring institutions. The occurrence of an environmental shock that impacted institutions as a whole triggered a critical juncture. The consequences, accompanied by a reactive way of dealing with the shock and learning, left a legacy that can become a lasting institution. According to Mahoney, Aranha & Filgueiras (2016), when a method is used to deal with the shock, junctures of great magnitude become critical, and it turns increasingly difficult to return to the initial stability (Mahoney, 2002).

As stated by Mahoney and Thelen (2010), the process of institutional change is initiated by exogenous factors and explained by endogenous factors. In this process, change stems from the behavior of both internal and external agents, and these are influenced by context and institutional forms. It is worth noting that validations and sanctions are experienced by the agents due to benefits that are perceived by all involved.

Conclusion

We found that all the essential elements for transformation at work were already present in the environment. Those are instrumental features such as horizontal management; open communication between managers and employees; hierarchy based on delegation of tasks and trust between parties; work measured by performance rather than hours worked; and technological tools for remote communication and performance. The change was limited because of cultural resistance.

The external shock suffered by the organizational system quickly led to the adoption of remote work. This impact allowed individuals in the organization to experiment new ways of working and using technological tools. This experience showed how technology meets the needs for work outside the company environment. The acceptance of this practice evidenced what Bush called "instrumental efficiency”, that is, habits that contribute to the precision of the decision-making process. The switch to home office was followed by new technologies, prioritizing instrumental behaviors over ceremonial ones.

Culture plays an important role in change by mediating the use of technological tools. As Pessali highlights, the institutional context contains both ceremonial and instrumental behaviors that are important and provide valid results for organizations.

The institutional advancement conveyed by progressive change has modified the value structure, which has resulted in a change in the rate of ceremonial dominance. The mindset that work should only be performed with the presence and hierarchical supervision of the employee has been set aside. Instrumental values came into use and were transformed into instrumental efficiency and the use of technological tools to solve problems, originating an institutional breakthrough.

The basic contribution to the theory is in the addition of discussions regarding institutional change. The theory discusses that change happens on a larger scale, slowly and gradually as a natural process of institutionalization. However, our research shows that shocks in organization fields have impacts that provide rapid and radical change. The current scenario is dynamic and demands an immediate adaptation from the organizations. This provokes changes that are put into practice in a short period of time. Brief experiences caused by major impacts on the environment may be able to break the structure of the organizational culture, which eases the implementation of rapid transformations.

Our research also points out that home office is something that can already be adopted by many organizations, but those with more traditional organizational cultures tend to resist the change. A need arises to align hierarchies and control mechanisms before making any changes in order to minimize conflicts that may arise.

We point out that home office work has been widespread in several areas and was maintained in the administrative modality after the pandemic slowed down. Even though the adoption of remote work is still incipient, it is possible to perceive the interest of healthcare organization managers, employees, and other companies. Home office offers control, performance, and execution tools that can be monitored by management. Our findings can contribute to managers and workers interested in applying a different way of working in their organizations. Understanding the adaptation of the organization's members is a key factor in breaking down barriers that restrict change. Therefore, professionals can devote energy and attention to other related issues, such as information security and relationships with other organizations.

In the social context, our study has some implications. For example, the implementation of new technology impacts the trust relationships between the organization's internal and external users. By analyzing the implementation of home office in a supplementary healthcare organization, we identified that it is possible to maintain and raise the levels of control and performance, as well as build relationships of trust and cooperation in the work environment. Communication with the use of digital tools provides agility and speed, making room to advance in other activities. Therefore, communication and trust arise as a positive response to social interactions.

Our study has limitations regarding the individual's personal and family advantages and disadvantages because the research scope is limited to work arrangement. The detailed description of the investigated phenomenon enables other researchers to understand the case, allowing a vicarious experience. For future research, we encourage studies that explore advantages and disadvantages focusing on the individual. Additionally, we recommend the application of different strands of Institutional Theory, as well as the use of a quantitative methodology based on the evidence presented in this study.

References

- Almeida, F., & Pessali, H. (2017). Revisiting the evolutionism of Edith Penrose’s the theory of the growth of the firm: Penrose’s entrepreneur meets Veblenian institutions. Economia, 18(3), 298-309.

- Alvim, M.B. (2006). The relationship between man and work in contemporary times: A critical view based on Gestalt Therapy. Studies and Research in Psychology, 6(2), 122-130.

- Aranha, A.L., & Filgueiras, F. (2016). Accountability institutions in Brazil: Institutional change, incrementalism and procedural ecology. Brazilian Journal of Political Science.

- Attaran, M., Attaran, S., & Kirkland, D. (2020). Technology and organizational change: Harnessing the power of digital workplace. In Handbook of Research on Social and Organizational Dynamics in the Digital Era. IGI Global, 383-408.

- Ayres, C.E. (1944). The Theory of Economic Progress. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 317.

[Crossref]

- Ayres, C.E. (1961). Toward a reasonable society. University of Texas Press. Austin, Texas.

- Baptista, J., Stein, M.K., Klein, S., Watson-Manheim, M.B., & Lee, J. (2020). Digital work and organisational transformation: Emergent digital/human work configurations in modern organisations. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 29(2), 1-10.

- Bellini, C.G.P., Donaire, D., Santos, S.A. dos, Mello, A.A.A., & Gaspar, M.A. (2011). Telework in the development of information systems: A study on the profile of knowledge teleworkers. Administrative Sciences Journal, 17(3), 1029-1052.

- Braz, M.V. (2020). The covid-19 (SARS-COV-2) pandemic and the contradictions in the world of work. R. Laborativa, 9(1), 116-130.

- Burns, J., & Scapens, R.W. (2000). Conceptualizing management accounting change: an institutional framework. Management accounting research, 11(1), 3-25.

- Bush, P.D. (1983). An exploration of the structural characteristics of a Veblen-Ayres-Foster defined institutional domain. Journal of Economic Issues, 17(1), 35-66.

- Bush, P.D. (1987). The theory of institutional change. Journal of Economic Issues, 21(3), 1075-1116.

- Cheluchinhak, A.B., & Cavichiolli, F.R. (2010). The theory of the leisure class. 1st Edition. Routledge. New York, USA. 13(1).

- Creswell, J.W. (2010). Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research design. In Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research design. 3rd Edition. Bookman Publications. Porto Alegre, Brazil.

- Dery, K., Sebastian, I. M., & van der Meulen, N. (2017). The Digital Workplace is Key to Digital Innovation. MIS Quarterly Executive, 16(2), 135.

- Elsner, W. (2012). The theory of institutional change revisited: The institutional dichotomy, its dynamic, and its policy implications in a more formal analysis. Journal of Economic Issues, 46(1), 1-44.

- Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

- Ferreira, A., & Rodrigues, J. (2012). The old institutional economics approach to research in accounting and management control: theoretical contributions. Iberoamerican Management Accounting Magazine, 2(19), 1-24.

- Filgueiras, V., & Antunes, R. (2020). Digital platforms, Uberization of work and regulation in contemporary Capitalism. Contracampo: Brazilian Journal of Communication, 39(1), 27-43.

- Freitas, B.L.T., Dourado, D.S., Boaventura, G.F., & Almeida, K.R.B. (2020). The History of Labor and the Creation of the CLT. Journal of Labor Law, Labor Process and Social Security Law, 1(1).

- Gajendran, R.S., & Harrison, D.A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Godoi, C., & Mattos, P. (2010). Qualitative interview: Research instrument and dialogic event. Saraiva Editora publisher. Sao Paulo, Brazil. 301-323.

- Graeff, C.B. (2020). Institutional change and judicial government: Conflicts between CNJ and Electoral Justice (2005-2015).

- Groen, B.A., van Triest, S.P., Coers, M., & Wtenweerde, N. (2018). Managing flexible work arrangements: Teleworking and output controls. European Management Journal, 36(6), 727-735.

- Hau, F., & Todescat, M. (2018). Telework in the perception of teleworkers and their managers: Advantages and disadvantages in a case study. Navus-Management and Technology Magazine, 8(3), 37-52.

- Haubrich, D.B., & Froehlich, C. (2020). Benefits and challenges of home office in information technology companies. Gestao & Conexoes Magazine, 9(1), 167-184.

- Hozdic, E., & Butala, P. (2020). Concept of socio-cyber-physical work systems for Industry 4.0. Technical Journal, 27(2), 399-410.

- Howcroft, D., & Bergvall-Kareborn, B. (2019). A typology of crowdwork platforms. Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 21-38.

- IBGE. (2020). Agencia IBGE noticias. 19/12/2020.

- Junker, L. (1982). The ceremonial-instrumental dichotomy in institutional analysis: The nature, scope, and radical implications of conflicting systems. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 41(2), 141-141.

- Junker, L. (1983). The conflict between the scientific-technological process and malignant ceremonialism. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 42(3), 341-352.

- Kyriazis, N.C., & Zouboulakis, M.S. (2005). Modeling institutional change in transition economies. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 38(1), 109-120.

- Lacasa, I.D. (2014). Ceremonial Encapsulation and the Diffusion of Renewable Energy Technology in Germany. Journal of Economic Issues, 48(4), 1073-1093.

- Law No. 13,467 of July 13, 2017. (2017). Amends the Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT), approved by Decree-Law No. 5,452 of May 1, 1943, and Laws No. 6,019 of January 3, 1974, 8,036 of May 11, 1990, and 8,212 of July 24, 1991, in order to adapt the legislation to the new labor relations. Brasília, DF.

- Lowndes, V., & Roberts, M. (2013). Why institutions matter: The new institutionalism in political science. Bloomsbury Publishing. London, United Kingdom.

- Lyytinen, K., Nickerson, J.V., & King, J.L. (2020). Metahuman systems=humans+machines that learn. Journal of Information Technology, 36(4), 427-445.

- Mahoney, J. (2001). The legacies of liberalism: Path dependence and political regimes in Central America. JHU Press. Baltimore, US state.

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2009). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power. Cambridge University Press. New York, USA.

- Mantymaki, M., Baiyere, A., & Islam, A.N. (2019). Digital platforms and the changing nature of physical work: Insights from ride-hailing. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 452-460.

- Merriam, S.B. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and Expanded from" Case Study Research in Education". Jossey-Bass Publishers. San Francisco, USA.

- Metzger, J.L. (2011). Permanent change: source of hardship at work? Brazilian Journal of Occupational Health, 36(123), 12-24.

- Miranda, F.S.M.P. (2012). The change in the economic paradigm, the Industrial Revolution and the positiveization of Labor Law. Dereito Electronic Magazine, 3(1), 1-24.

- Oliveira, M.C.S. (2005). Post-Fordism and its effects on employment contracts. UFPR Law Faculty Magazine, 43.

- Pacini, S., Tobler, R., & Bittencourt, V.S. (2023). Home office trends in Brazil. Article Portal FGV.

- Pandey, N., & Pal, A. (2020). Impact of Digital Surge during Covid-19 Pandemic: A Viewpoint on Research and Practice. International Journal of Information Management, 102171.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, G. (2015). Expanding on Ceremonial Encapsulation: The Case of Financial Innovation. Journal of Economic Issues, 49(1), 127-142.

- Pereira, J.J.D.S., & Monteiro, M.S. (2020). Information technology in the organizational environment. Journal of Applied Social Sciences, 1(1).

- Rezende, F.D.C. (2012). From exogeneity to gradualism: Innovations in the theory of institutional change. Brazilian Journal of Social Sciences, 27, 113-130.

- Ribeiro, J.A., & Scapens, R.W. (2006). Institutional theories in management accounting change: contributions, issues and paths for development. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 3(2), 94-111.

- Rocha, C.T.M.D., & Amador, F.S. (2018). Teleworking: Conceptualization and questions for analysis. EBAPE notebooks, 16(1), 152-162.

- Rossato, E. (2001). Transformations in the world of work. Vidya, 19(36), 9.

- Rutherford, M. (1984). Thorstein Veblen and the processes of institutional change. History of Political Economy, 16(3), 331-348.

- Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications. California, United States.

- Scapens, R.W. (2006). Understanding management accounting practices: A personal journey. The British Accounting Review, 38(1), 1-30.

- Stake, R.E. (2016). Qualitative research: Studying how things work. Silpakorn Educational Research Journal, 3(1-2):257-260.

- Tavares, F., Santos, E., Diogo, A. & Ratten, V. (2020). Teleworking in Portuguese communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. 15(3):334-349.

- Teles, N., & Caldas, J.C. (2019). Technology and work in the 21st century: A proposed approach. Observatory Notebooks, 12, 1-35

- Tool, M.R. (2012). Value theory and economic progress: The Institutional Economics of J. Fagg Foster. Springer Science & Business Media. New York, USA.

- Veblen, T. (1909). The limitations of marginal utility. Journal of political Economy, 17(9), 620-636.

- Veblen T. (1961) Why is economics not an evolutionary science?. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 12(4):373-397.

- Vieira, D.M., & Gomes, R.C. (2014). Gradual and transformative institutional change: the influence of advocacy coalitions and interest groups on public policy. Organizations & Society, 21(71), 679-694.

- Weking, J., Stocker, M., Kowalkiewicz, M., Bohm, M., & Krcmar, H. (2020). Leveraging industry 4.0–A business model pattern framework.?International Journal of Production Economics, 225, 107588.

Received: 18-Mar-2024, Manuscript No. ASMJ-24-14620; Editor assigned: 21-Mar-2024, PreQC No. ASMJ-24-14620 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Apr-2024, QC No. ASMJ-24-14620; Revised: 17-Apr-2025, Manuscript No. ASMJ-24-14620 (R); Published: 24-Apr-2025