Review Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 1

Culture, Conflict and Team Management in I4H: Experiential Learning in Business Practice to Support Community Development Entrepreneurship

James R. Calvin, Johns Hopkins University

Joel Igu, Johns Hopkins University

Abstract

Introduction: The Carey Business School's Innovation for Humanity (I4H) project leverages experiential learning in its collaboration with international partners that work towards achieving the United Nation's 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).The theory behind the development and evolution of I4H is rooted in literature that describes culture, experiential learning and the business of social impact the I4H project equips teams with cultural and conflict management training, business communication skills and analytical tools to solve organizational problems in multicultural settings. Purpose: This study has two main aims. It seeks to describe I4H, a Business School experiential learning program, exploring the model that I4H uses to address culture and conflict in teaming in its international projects. This study also identifies student challenges and solutions to problem solving in the context of culture, conflict and teaming in I4H and proposes that these lessons learned are transferable in the context of similar experiential learning projects. Methods: Student and programmatic experiences from the last two years of I4H were analysed qualitatively using grounded theory. Student experiences as reported from their project feedback were coded using grounded theory into themes that explored their challenges and learning points from completed projects. Themes on solutions to these challenges were also explored. Results: In the last two years, I4H has worked with 32 sponsors from five countries. Students reported five groups of challenges: Cultural challenges, communication based challenges, conflict based challenges, team related challenges, and unforeseeable challenges. These challenges were mitigated using concepts from I4H and its supporting course, Solving Organizational Problems. Limitations: The I4H program is limited to the Carey Business School, and its generalizability to other experiential learning programs may be confounded by the other learning experiences that students encounter at the Carey Business School. Conclusions: Carey Business School's I4H experiential learning model is transferrable and creates value through skill transfer, social impact and reciprocal community development. The I4H program successfully deals with multicultural issues in international collaboration, conflict resolution and teaming. It has direct impact through bilateral knowledge and skill transfer, and indirect impact through initiatives that it inspires, and fosters.

Keywords

Organizational Culture, Cross-Cultural Business, Sustainable Development Goals, Social Entrepreneurship, Experimental Learning, Conflict and Team Management.

Introduction

Two years after its founding in 2007, The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School initiated an experiential learning based business and entrepreneurship discovery course in its Global MBA program. The Carey business School’s Innovation for Humanity (I4H) course is 8 to16 week experiential learning course that prepares fulltime MBA students for business leadership by engaging them with projects that ground them in culture, conflict management and team management. In keeping with the business school’s tagline “Business with Humanity in mind”, the I4H program worked with partners that provided social impact as part of their business model. From I4H’s inception in 2009, it initially focused on the eight Millennium Development Goals, i.e. poverty reduction, health and nutrition, education, water, environment, sanitation and sustainability. Since 2015, this I4H model of experiential learning has been updated to cater to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) toward the year 2030. The adopted approach to transferable business knowledge and skill learning relies on learning theory and concepts advanced by Argyris & Schon, 1974; and Argyris, 1977 as a proponent of theories of action toward the transfer of double-loop learning and organizational learning. The two-action learning applications intersect as well as them helps to identify and improve faulty processes, which are core for the project-based interest of the I4H course and project work implementation. Later research has validated the merits of experiential leaning in keeping with these older theories (Bevan, 2012). Furthermore, the development of an I4H project plan is for in-country execution and is jointly developed with the project sponsor so that the work in place is carried out in concert with project sponsor feedback and guidance. Doing so requires the synthesis of data and information resulting in simplifying often-complex sets of organized knowledge akin to Nonaka (1994), as cited in Fernandez & Sabhenal (2010). In recent times, the I4H project team’s purpose is to gather, build and transfer proposed ideas and information as useable knowledge to a given project sponsors whose desire and interest is to address and meet real-time needs of one or more of the SDGs. The proposition can be a doable contribution, define and deliver as an actionable recommendation that is intended to meet a specific circumstance as well as a business option for adoption and implementation by a given project sponsor. The goal of this paper is to describe the I4H program, explain its theoretical origins, design for social impact, and highlight student experiences through their challenges and solutions using I4H principles. This paper contributes to academic knowledge by examine a new experiential learning program, I4H, as a replicable model for other business schools and academic programs.

Brief Overview of I4H

The I4H course is part of the MBA education of all fulltime students, and seeks to temper the traditional MBA curriculum with skills that position Carey students well in an increasingly diverse and global world. At the Carey Business School, teachers and experiential learning coaches are collectively mindful of the limits of a business education mission. It is important to note that the I4H curriculum model is receptive to continuous adaptation and modification that enables openness to meet the potential of knowledge co-creation with I4H project sponsor partners, and the evolving business world in our era of rapid globalization. Openness to exchange and possibility is essential in this process, especially with the growing number of partners the I4H program has had over the years. The primary goal of Johns Hopkins Carey I4H project teams is to frame and shape applicable business knowledge and skill transfer that is critical to the realization of achievable practical goals desired by social entrepreneurs, citizens, and business and government organizations. I4H four to five member teams are deliberately built to reflect cultural and geographic diversity amongst team members. Teams are assigned to projects that are located in geographies different from their previous residential and professional experience and created in such a way that team members’ professional skills most closely match the industry or task that is associated with assigned projects.

Hence, I4H program analysis births a theory of action science-based experiential learning that seeks to inculcate knowledge transfers that link business with entrepreneurship skill application. These business practices become concrete in the geographies where I4H teams are deployed (Table 1).

| Table 1 I4H Program Sponsors and Locations (2016-2018) | |||

| Country | City | Sponsors | SDG Goals Targeted |

| Peru | Lima | Autoridad para la Reconstrucción con Cambios-ARCC, Hospital San Juan de Lurigancho (HSJL), UDEA Project, Asociacion UNACEM, Asociacion Taller de los Ninos, MINEDU, Red de Energia, Yaqua | Goals 1, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| Lircay | Canto Grande, Grupo Fundades, Lircay | Goals 8, 9 | |

| India | Hyderabd | ICRISAT, LV Prasad Eye Institute, SaciWATERs, Dr. Reddy’s Foundation, Innova | Goals 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 |

| Rwanda | Kigali | Azizi Life, Condom Manufacturing Business Plan, E-waste Recovery Enterprise Plan, Legacy Clinics, Great Lakes Energy, Inyungu, Nibakure Children’s Village, Perfect Chalk Factory | Goals 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17 |

| Ethiopia | Addis Ababa | AGOHELMA, Catholic Relief Services | |

| US | Jemez | Jemez Community Development Corporation (JCDC) | Goals 1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16 |

| Denver | International Centre for Appropriate and Sustainable Technology | Goals 4, 9, 15, 16, 17 | |

Experiential Learning Theoretical Frameworks Guiding I4H Design in Culture, Conflict and Team Management

Experiential learning is an effective way to expose teams to cultural learning in organizational settings. Schein (1990) answers the question; “what is culture?” by employing a multi-approach paradigm. He states, “culture, like role, lies at the intersection of several social sciences and reflects some of the biases of each-specifically, those of anthropology, sociology, social psychology, and organizational behaviour”. Taking this intersectionality, a step further, Hofstede (1997) offers the perspective that “culture is always a collective phenomenon, because it is at least partially shared with people who live or lived within the same social environment, which is where it was learned…culture is learned, not inherited”. More recently, the narrative of culture in organizations that has emerged from the on-going Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour (GLOBE) international study posits that it is assumed that knowing values in a culture tells us about what actually happens in that culture. GLOBE calls this the onion assumption, in reference to Hofstede’s (2006) onion diagram that refers to levels of culture. The complexity of cultural elements in cross-cultural collaboration is so deep that theoretical exposure to impactful learning is difficult, especially within short timeframes. Experiential learning bridges this gap using applied methods to examine this complexity in practical ways.

Experiential learning comes with its own difficulties, but this is the crux of the argument for experiential learning. In the context of I4H, these lessons are learned in the safety of an academic environment with students guided by faculty and their collaborating sponsors. Professionals are able to develop new skills and perspectives, learn new teaming strategies and encounter new cultures for the first time. These challenges are overcome through modules deliberately designed for these eventualities. Thus, the gains of experiential learning are harnessed while these challenges are mitigated.

There are three lenses which I4H explore design roots theory in culture, conflict management and teaming. These include:

1. Experiential skill transfer

2. Social entrepreneurship

3. Community development

Lens 1: I4H Experiential Skill Transfer in teams

First, I4H’s experiential learning course has been rooted in experiential learning theory. In particular, Kolb’s (1984) framework for experiential learning rooted in previous work done by Lewin (1938); Dewey (1997) and Piaget (1951) has influenced the methodology of experiential learning practice in the I4H model. Not only do students take part in observational activities during I4H, but also they engage in concrete business practice, and are also able to apply leanings to other projects within their MBA curriculum before graduation. While I4H is an organizational behaviour course whose curriculum is focused heavily on teaming, culture and communication, it is supported by an accessory course called Solving Organizational Problems (SOP). SOP targets specific skills in team project development and uses tools like team contract designing modules, project scoping guidelines and logic tree models to supplement I4H teachings with project management skills that students will use in the field. Johnson et al. (2006) refer to The Oxford Dictionary, which defines skill as expertness, or practiced facility in doing something. In this context, skill is the behavioural component of cultural competence, and includes abilities such as foreign language adeptness, adapting to the behavioural norms of a different cultural environment, effective stress management, conflict resolution skills, and aptitudes.

I4H project teams experience the full range of skill acquisition to be applied onsite as business practice in line with these recommendations. De Meuse in a Korn/Ferry Institute study of its validated T7 Model of Team Effectiveness states “successful teams become stronger when members learn to work together. Congden et al. (2009) mention the need for sustaining cross-cultural communication competence to get to a desired level of multicultural team performance and have cleared acceptable goals” This is in keeping with The Wisdom of Teams (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993:2015); complementary skills are built. Professional skills are layered with cultural skills. What results from this intentional team building and site choice, is a rich ground for experiential learning in which cultural polarity, geographic uncertainty and skillset diversity characterize course activities. The dynamics of this team-based experiential learning is further augmented from Lencioni’s (2002) “The Five Dysfunctions of a Team”, because I4H teams must consider and reconcile trust building and trust sustenance, work through conflict, and demonstrated accountability. Students are led through teaming and cross-cultural themes throughout the duration of their I4H course with an assigned client, at the end of which clear deliverables are met under a series of strict deadlines that culminate in an academic grade based on the quality of work delivered.

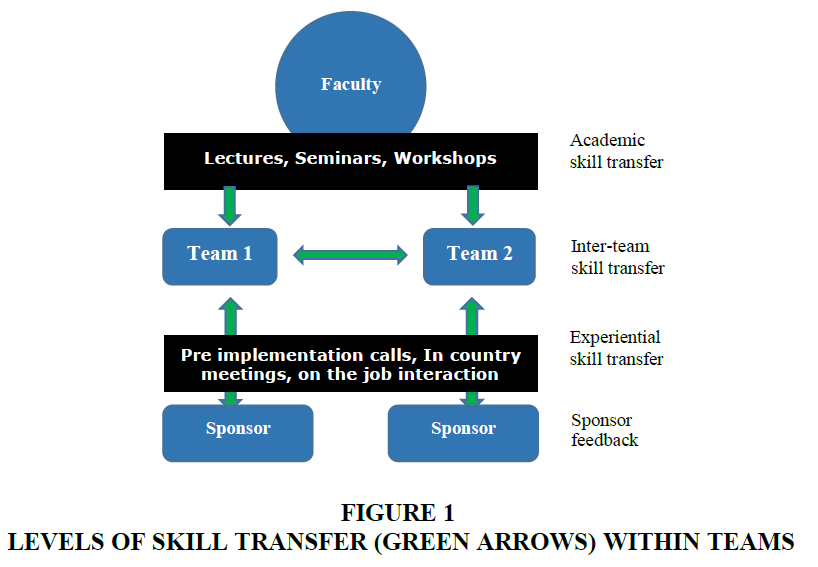

I4H students learn new skills like research, data analysis and cultural communication, buttressed by complementary skills possessed by team members, and guided by the supporting curricula of I4H and SOP. One team reported skill transfer through leadership rotation as student reports; “Throughout our experience, we all took initiatives to learn new skills both inside and outside our existing expertise and facilitated learning by spreading leadership across the team”. A double feedback loop and weekly team check INS ensures that problems in experiential skill transfer are identified immediately, and discussed in class sessions. I4H faculty are able to step in when teams cannot resolve identified issues internally, and in many cases serve as a communications liaison between a team and its sponsor. For example, when team and sponsor expectations are not aligned, most commonly, when sponsors expect too much from an I4H team, faculty are able to set up a call with the team and sponsor, and help to realign these expectations. This is important when team skills are not suited to sponsor expectations, or when skill transfer which is shown in figure 1; is slow or incomplete–ensuring that skills transfer develops organically, and are efficiently targeted towards client expectations.

Lens 2: Social Entrepreneurship

A second piece of I4H is that it is fundamentally embedded in social impact. In the current modern era of entrepreneurship, the triple bottom-line is becoming more valued by organizations. Values and ethics are increasingly becoming necessary components of organizational culture and leadership. At the time of the first modern era of globalization, Adam Smith introduced a world changing idea in The Wealth of Nations (1776) that advanced entrepreneurship in a changing and industrializing world where countries could pursue goals in their best interests. Several decades after Adam Smith, the economist David Riccardo offered more entrepreneurship principles that enabled economic development as the theory of comparative advantage, which sought to maximize human capital, trade and natural community, country and regional assets. By the early nineteenth century, Weber (1904) had articulated that social culture was a driving force of entrepreneurship because of risk taking by entrepreneurs. Later in the twentieth century, the economist Schumpeter (2014: 1942) argued persuasively that innovation is the critical dimension of economic change that includes entrepreneurial activities and market power. Still in these times, the dictates of market economies yield profits for companies while often creating haves and have-nots in many communities and regions across cultures and societies. What are the alternatives to this inequality creating dynamic, if any? One consideration is the role of community-based economies, an alternative that business has a role in, and can contribute to shaping. Drucker (2006) characterized entrepreneurial strategies as purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management, and as purposeful systemic discipline. It has provided perspective on the role of social entrepreneurship as being in the interest of business and society because the purpose of business should be more than profits-impactful business needs impactful communities for mutual well-being. Given the aforementioned, Thomas Piketty in the Economics of Inequality (2015) has raised the question of what strategies are most effective to improve the actual standard of living of the least well off in societies. Further toward the idea and goal of more than profits as purpose, Ted London in Impact Enterprise for the Base of the Pyramid (2016) offers for consideration: While these ideas are powerful: Creating enterprises with impact. It is using the power of market-based approaches to address social issues. Some people and not others about what business generated degree market-based approaches best address social issues hold that perspective.

The evolution of entrepreneurship theories increasingly therefore centres on the impact that business has on communities, and the role that these communities play in this impact. The author readily admits that this is not a very new idea or strategy. For I4H project teams, the business method and approach is imbedded in the realization of community partnership efforts that leverage entrepreneurship as a vehicle that drives innovation, foresight and creativity. This trifecta makes problem solving practical in meaningful ways for teams that are intentionally structured to contain them. I4H project teams contribute to economic and social inclusion and the real-time business practice efforts they use to focus on one or more of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for partners whose activities pursue SDG outcomes. Specific business practices occur at community, region and country levels globally in several countries.

In recent years there have been significant advances made by I4H experiential learning and practice. The evidence of business knowledge and skill transfer is demonstrable after nine years of the introduction of the I4H teaching business model. Practical outcomes of teamwork are being manifested in cultures and societies in several countries across the world where the challenge and need is clear. These projects tackle issues that address social justice, broadened cultural equity and participation. I4H teams effectively meet these challenges and needs through the kind of social entrepreneurship described above. Since the intent of the pedagogical approach in I4H is to promote team learning, the structure of experiential learning requires transfer as a fundamental value principle and thus transfers adaptable business knowledge and skill via active social entrepreneurial collaborating. The pursuit of social entrepreneurship or social business as a viable business practice provides work choice options and life choice options for Global MBA students.

The Carey Business School is not alone in leveraging the power of experiential learning in a course that addresses multiculturalism and globalization. An increasing number of business schools offer social innovation courses as a way to create social impact, often deploying social entrepreneurship driven business student teams to project sites in external locations. Perhaps this suggests a growing realization that these skills are important for all future business leaders today. The Carey Business School is unique in the sense that all fulltime MBA students are exposed to this course as part of their graduation requirements. As learners engage business schools to seek out professional pathways, there is an opportunity for colleges and universities to broaden the scope of social entrepreneurship and social innovation as reported in Stanford Social Innovation Review (November 2016).

I4H sponsors are preselected to reflect the opportunity for social innovation and social impact. That being said, many of the selected organizations that collaborate with the Carey I4H programs are for-profit and I4H MBA students typically have professional work experience in organizations that are primarily profit oriented. For many students, working with a non-profit, or a for profit that values social impact is a new experience. Inculcating new perspectives on project deliverables-perspectives that focus on social entrepreneurship-is an enriching lesson these students learn because it not only ensures that Carey MBA students understand the benefits of socially impactful solutions, but it also enables them exercise creative thinking and innovative problem solving strategies when faced with a business problem. When there are multiple solutions to a problem, those that have additional social benefits are prioritized, ensuring that not only is a profit based deliverable satisfied, but its social impact can be measured and quantified. This experiential learning approach inadvertently leaves students imbued with the appreciation of the values and ethics of business in the organizations they work with, and the careers they choose after their MBA studies are complete, hopefully.

Lens 3: Business for Community Development

A third element explored by the I4H course is community development; the intersection of business, community and society. I4H contributes to future wellness in communities and society. Scholars argue that business can and should play a realistic role in the ethical pursuit of sustainable economic development and wellbeing at the community level. Yunus (2010) in recent years is credited with introducing social entrepreneurship in action toward the development and implementation of solutions to social, community, cultural and environmental issues. In brief, microfinance and the advent of Yunus (2010) Social Business are an important direction of capital to serve humanity is pressing needs in low resourced regions and countries. The structure of his proposed social business is a non-dividend company, planned to be financially self-sustainable, and the profits of the business are reinvested in the business itself (2009, 2011, and 2014). In succeeding years, Jacqueline Novogratz started the Acumen Fund in 2001, along with other participants in the space of global development, and that effort has yielded successful strategies that support the development and implementation of sustainable solutions to big problems in multiple communities around the world.

Still another angle to consider is pliability and the potential for reciprocation. The intersection of experiential learning and business knowledge transfer that supports social entrepreneurship for community economic development purposes is rich in opportunities for reciprocity. Concerning action oriented knowledge co-creation and transfer, the social psychologist Robert B. Cialdini presents the idea that when the role of reciprocation is joined together by a common sense of obligation, parties mutually gain. The Cialdini principle of reciprocation also connects to a sense of personal obligation that is of essential importance as motivation for the experiential learning approach and method of experiential learning in Innovation for Humanity (I4H). Cialdini (2007) among other thought leaders from the domain of sociology find reciprocation to be pervasive across all human cultures and societies. The importance of principle also correlates with John Dewey who has Experience and Education states, “When education is based upon experience and educative experience is seen to be a social process, the situation changes radically”. Dewey is at the foundation of experiential learning as a life-long practice. Reciprocation is also a foundation for the active business education practice that connects directly with community economic development, and where perspectives of education, business and government can be brought together.

It is essential for I4H teams to discover the linkage between community development and community economic development. As such, two definitions of community development that follow are applicable to the purpose, goals and interest of I4H. Community development is discussed by the UN United Nations (UN, 1948) who describe as a main priority, exploring possibilities, methods and ways to “achieve international cooperation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character or nature”, in relationship to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which is the current opportunity, the UN’s vision and efforts in the pursuit of community development contends and remains: “Community development is a process designed to create conditions of economic and social progress for the whole community with its active participation and fullest possible reliance upon the community’s initiative. (United Nations, Quoted in Head, 1979)” A second reference is derived from The Community Development Society (CDS), which states: “We view community development as a profession that integrates knowledge from many disciplines with theory, research, teaching and practice as important and interdependent functions that are vital in the public and private sectors. We believe the Society must be proactive by providing leadership to professionals and citizens across the spectrum of community development. In so doing, we believe the society must be open and responsive to the needs of its members through provisions and services, which enhance professional development. (CDS, 2017)”. Accordingly, the intent and purpose of the UN Global Compact established in 2005 has allowed for thoughtful ideation and co-creation through which business directly engages with communities to pursue goals and interests in common. The Global Compact guiding principles challenge business to voluntarily commit to developing and implementing social business efforts in many countries. The linkages of business, university and community partners through The Global Compact continue to spur the development and adoption of active learning. Action-learning curricula allow for the building of knowledge and skills (as learned social business and social entrepreneurship) practices that eventually become real-time community applications. This is true in both socially focused start-up businesses and the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities of established business ventures; nurturing long-term community relationships and partnerships.

I4H teams demonstrate community development according to these theories because they transfer practical business solutions that improve, enhance and sustain social entrepreneurship gains at local and community levels. Since the transfer of business capacity knowledge in I4H is two-way cross-cultural exchange done in community settings, its impact occurs bilaterally; at the community level, and also internationally, with I4H students retaining and using lessons learned professionally after graduation. Carey Business School is a signatory of the UN Global Compact and anchors its business education toward fulfilling the pursuits of “Business with Humanity in mind”-an affirmation of Carey’s intention to deliver value to communities in all business settings. As the need continues to better understand, invent, build and sustain social business and social entrepreneurship approaches as community useable tools for making change, there is the empowering factor of “doing community business entrepreneurship is integral to future sustainability of communities, regions and nations around the world as it helps to spur economic development (Calvin, 2012)”.

For I4H teams, community development is a central theme that all projects encompass, especially because preselected projects have strong MDG/SDG components. The amorphous nature of broad MDG/SDG goals is filtered and streamlined by the experiential learning process that teams go through. The interaction between I4H teams and communities within which they work on projects, magnifies the opportunity to understand and realize community objectives. For example, a team member that worked in India said “As MBA students I think we tend to focus on the Power Points, spread sheets, and presentations. It’s only when you are on site and see a child on the operating table receiving surgery does it really stand out….” This quote drives home the fundamental understanding of social impact in the context of community development. The quoted team goes on to report intersections between parents, the sponsor and the larger community. Many teams reported a strong need to be sensitive to the norms and cultures of locations in which they worked (most I4H students work in countries they have never previously been to), and linked this realization to a recognition of their own individual cultures, and how both contrast with the culture of the US, where the Carey Business school is located.

Methodology in Student Data Collection

To examine the experience of students through their own eyes, data from team reports was analysed qualitatively. 36 reports were assessed over a two-year period (2017 and 2018). Student and team responses in the feedback section of these reports were coded in Excel 2013 using grounded theory (Strauss 1994). Emerging themes were condensed and categorized in MS word. There were 36 teams with 24 sponsors and 130 student respondents. Teams had a minimum of 2 members and a maximum of 5.

Results: Challenges and Solutions in I4H Program

Themes from student reports had five broad groups of challenges: cultural, communication based, programmatic, and teaming and conflict, and unforeseeable challenges. In each category, students also reported the methods by which they navigated difficulties using I4H concepts.

Cultural Challenges

Problem

Students have to navigate religious and cultural differences in the populations they are expected to make impacts in. For many teams, intuitive and default problem-solving strategies are not viable in the cultural contexts they work. Implementation of solutions thus proves challenging. A student reported; “Another valuable take-away for all members of the team was just how challenging and important it is to have a strong cultural and contextual understanding of the areas in which you work”.

Solution

Teams reported the importance of understanding the culture in which they execute their projects. This often entails building and maintaining relationships with new people, asking questions and discussing the cultural implications of solutions with sponsors. One team said; “if one is to help the society in the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP), one cannot simply start from their end or their own idea. Research and interaction with the communities being served are necessary to truly understand their needs”. Teams have to study countries in which they are deployed, create country profiles prior to deployment, and voluntarily engage in cultural activities in country, while they are conducting their research and project implementation. In addition, many teams hold informal events in the US, with natives of the country in which they are deployed, asking questions and familiarizing themselves with the cultural norms of their destination, preparing them further for in-country experiences. Many preconceived notions about I4H destinations are disabused before I4H teams eventually arrive at their project locations, and while in country, teams report gaining new perspectives on previously held cultural ideas.

Communication Challenges

Problem

Intra-team communication and team-sponsor communications are a major challenges faced by I4H teams. The US is a low context culture and many sites where projects are executed are high context cultures (Peru, India, Rwanda etc.) The time difference between the US and target locations complicate this problem further. Additionally, the virtual nature of early communications (phone calls, video conferencing and emails) further exacerbates cultural communication differences.

Solution

Teams draw on communication primers from I4H to ensure that communication problems are addressed. They build on these primers and organically develop communication corridors and styles that ensure that misunderstandings are mitigated. Many teams relied on building strong relationships with sponsors to strengthen clear communication. As a team discovered; “Working within a diverse team can pose unique challenges, but communicating openly and building strong relationships allowed the team to thrive”. Repeating phrases and themes during phone conversations helped teams identify misunderstandings immediately and proactively define a mutual understanding of issues discussed. Teams reported that they had to “clarify the new requests of the client or project” and “discuss internally which of the requests we felt we had the capabilities to contribute to”. One team in Rwanda received corporation from their sponsor but were not making headway because of a lack of data, despite the perceived harmony in team-sponsor relations. They solved this problem by internal team consultations and a decision to be more firm about making demands for information from sponsors. This quote from the Rwandan team highlights the success associated with this approach: “After many internal discussions within the group, we decided that we needed to be sterner in our pursuit of data, and shift our dialogues with the officials, rather than accepting everything at face value. Once we made a conscious decision to do so, our project began to come together in ways that were unimaginable”.

Programmatic Challenges

Some I4H problems were directly linked to programmatic issues, for example, a team in India had a redefined scope of work after multiple iterative expectation defining meetings with their sponsors. They were eventually expected to deliver a research-based document that they felt unable to deliver effectively in a short time frame because of a perceived skill set mismatch.

Solution

This predominantly American team was ultimately able to impress their Indian client. They did so by exploring iterative expectation definitions with their client- Agricultural innovation enterprise- using course concepts from SOP. They report; “This first-hand experience will prove invaluable when evaluating that data, because it taught us just how crucial it is to question not just the data itself, but the methodology and quality of research that created the data”. Other teams that were faced with programmatic challenges recognized the importance of identifying and leveraging stakeholder relationships in solutions development; “The I4H experience taught me the importance of balancing different stakeholders and their needs”.

Programmatic challenges in dealing with perceived sponsor inefficiencies often proved challenging for I4H teams, who were acquainted with different communications and reporting standards in US based organizations. These groups were able to navigate these challenges by drawing from I4H course material, for example; “the training that Innovation for Humanity gave the team in bridging cultural and societal divides, for instance, helped the team frame their exasperation with several components of client communications within the context of mitigating and overcoming the obstacle with a more cosmopolitan understanding.”

Ultimately, most teams realized the need for strong relationships in executing mutually successful I4H projects. A quote from a Rwandan team sums this up neatly: “No matter which business you are in, building strong relationships can get you far and result in indirect savings in costs”.

Teaming and Conflict specific issues

Teams often faced internal conflict and in many cases, conflict with their sponsors. Sponsor affiliated conflict was largely linked to expectations mismatch, and a perceived lack of access to vital project specific information teams required.

Solution

Every I4H team’s first deliverable is a team contract that highlights the strengths and weaknesses of team members, and clearly outlines the rules and guidelines that team members are expected to adhere to. This team contract also discusses conflict resolution mechanisms within the team, and eventualities when this team derived conflict resolution strategies fail. In such cases, faculty and project mentors arbitrate conflict. Course concepts explore conflict resolution mechanisms and so far, every team has been able to operate successfully throughout the course of the I4H project experience. “The team grew immensely during this project and learned not only about the sponsor organization and country but also about themselves and about the importance and value of diversified teamwork.”

Unforeseeable Emergencies

In a few cases, teams were faced with unexpected situations due to political issues. In one case, a team member was unable to continue his MBA because of the political situation in his home country, Zimbabwe, and had to discontinue project work after several weeks of being committed to a project in India. In another case, a Team in Peru lost half of its team members because of US travel advisory changes to Peru; “Our team strength was reduced by half and when our trip to Lircay got cancelled due to potential unrest in Lima”.

Solution

These teams were still able to complete successfully their projects after consultations with faculty and academic directors determined that these projects would still be viable and satisfy academic course requirements. Team members reported bonding more strongly because of these external challenges, and team sponsors were receptive and supportive during these unpredictable changes.

The Evolution of 14H as a Living Model for Social Change

As of March 2019, the I4H will have completed 138 projects in eight countries with multiple such project sponsors. In some instances, the I4H project work has been with project sponsors for a period being three years or longer because systemic and meaningful derivative change takes time, as does new entry and new strategies for incorporating business practice. I4H is also a networked partner with universities in project partner countries, Catholic Relief Services, the UN and other strategic partners. Many of these projects have been impactful to partners, students, and communities.

An example of positive feedback from an I4H project sponsor came from the Universidad Para el Desarrolio Andino (UDEA) in Lircay, Peru. In this mining heavy region, an I4H project team was able to contribute an idea to implement an entrepreneurship program for young people to pursue work that is not dependent on mining for economic stability and the financial sustainability.

I4H has also indirectly stimulated impact in entrepreneurship through new partnerships outside the scope of its academic requirements. For example, I4H-Mzuzah partnership began in Accra, Ghana in 2017, when I4H students participated in Mzuzah Convergence conference. This conference involved millennial participants from nine African countries with a sharp focus on sustainability and improved economic livelihood in communities. A year later, another I4H student anchored the hosting of this conference at Johns Hopkins-the first time it was held outside Africa since it 8-year history. The Hopkins version of the Mzuzah Convergence (2018) had a focus on sustainability and entrepreneurship and created opportunities for African entrepreneurs, eventually leading to the formation of an Africa Business Club at Carey by students who had engaged with the I4H experiential course. The I4H-Mzuzah partnership became a knowledge creating and sharing eco-system for ideas and actionable partnerships. A piece of its learning architecture is to build a knowledge sharing pool from which to begin sustainable knowledge and skill linkages for entrepreneurial purposes. At the Mzuzah Convergence Conference on Africa and sustainable business development in May 2018, the keynote discussion and resulting exploration and practice was about keeping ahead of the SDG’s by using the proper metrics to support the right kind of sustainable investments. It explored the rapid motion of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (2016) and opportunities to leapfrog African entrepreneurship through technology through the rise of entrepreneurship in Africa. Such applications of technology (for ex block chain, IoT innovation, and artificial intelligence in these settings) will require more experiential learning to achieve knowledge sharing and knowledge and skill transfers. Mandela Fellows and Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI) Fellows from several African countries were in Baltimore and they were joined real-time digitally by simulcast interactions with conference participants from Liberia, Uganda, and Nigeria-as well as by conference attendees from Europe, India, Asia, South America and the US in the room. The mutual goal and interest of the partnership with Mzuzah Convergence is to broaden business skill and sustainability interests in 2019, and in future years to come. We think that business knowledge and skill transfer is aided by the cross-cultural socialization between individuals as team members as they pursue a shared interest in problem solving activity for I4H project sponsors.

Conclusion: I4H is a Sustainable Business Practice

In this paper, we have discussed the I4H experiential learning model and approach with its focus on connecting skilled graduate business students with entrepreneurs and organizations. Cross-cultural partnership leads to business in support of SDGs transfers and adds vitality to communities. The ever-steady pace of change including geopolitical factors will redirect, at times, how the business knowledge transfer and skill discovery framework approaches influence the I4H business knowledge and skill transfer scope of delivery for both sustainable development and an experiential learning process by graduate students.

As a concluding thought, the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School espoused credo is “doing business with humanity in mind”, which is a core operating principle for Innovation for Humanity (I4H). I4H seeks to be a pathway to unite people on teams who will engage citizens through business in a common purpose, and to do so is to find and build together options for sustainable community economic and social development. It is affirmative that business has a role to play in the on-going development of livelihood and the instituting of realistic options in communities and society as outlined and framed by the SDGs. The capacity of I4H teams to engage in experiential learning and to become more cross-cultural in individual and team perspectives is enhanced by the capability of I4H teams to manage through team conflict that becomes effective team management.

Models that seek to replicate the I4H program must understand the value based approach and social impact intention of I4H and how these priorities are shared between sponsors, student teams and the business school, and seek to identify such value overlaps in their own practice. The iterative nature of I4H’s adaptation is also important, as student reflections and leanings provide guidance to faculty and curriculum reviewers to streamline training approaches for each new batch of students that come next. These student reflections also inform targeted modifications to the experiential portions of the I4H program.

Limitations of this Study

The Carey Business School’s I4H program is one of many other Business School courses at the Johns Hopkins University. As such, the experience of students in I4H is complemented by other courses they take simultaneously. Thus, student experiences and responses may not be explained solely by their experiential learning’s in I4H. This study also does not take into account the cultural differences in team compositions between the two years studied. It assumes that the matching process for I4H teams discounts these differences by placing students in countries that are different from their country of origin.

References

- Argyris, C. (1977). Double loop learning in organizations. Harvard Business Review, 55(5), 115-125.

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey-Bass.

- Bevan, D., & Kipka, C. (2012). Experiential learning and management education. Journal of Management Development, 31(3), 193-197.

- Calvin, J.R. (2012). Community business entrepreneurship, globalization, and future directions toward new sustainability. The Lisbon papers: Transformative leadership and empowering communities. Oxford, UK: Community Development Journal and International Association for Community Development.

- Chua, E.G., & Gudykunst, W.B. (1987). Conflict resolution styles in low-and high-context cultures. Communication Research Reports, 4(1), 32-37.

- Cialdini, R.B., & Cialdini, R.B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.

- Community Development Society(2017). Retrieved from http://www.comm-dev.org/about-us

- Congden, S.W., Matveev, A.V., & Desplaces, D.E. (2009). Cross-cultural communication and multicultural team performance: a German and American comparison. Journal of Comparative International Management, 12(2), 73-89.

- De Meuse, K.P. (2009). Driving team effectiveness. A comparative analysis of the Korn/Ferry T7 model with other popular team.

- Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education, 1938. New York: First Touchstone Edition.

- Drucker, P.F. (2006). Innovation and entrepreneurship. UK.

- Fernandez, I.B., & Sabherwal, R. (2010). Knowledge management systems and processes. ME Sharpe, Inc.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: Mcgraw-hill.

- Javidan, M., House, R.J., Dorfman, P.W., Hanges, P.J., & De Luque, M.S. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: a comparative review of GLOBE's and Hofstede's approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 897-914.

- Johnson, J.P., Lenartowicz, T., & Apud, S. (2006). Cross-cultural competence in international business: Toward a definition and a model. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4), 525-543.

- Katzenbach, J.R., & Smith, D.K. (2015). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Lencioni, P. (2002). Five dysfunctions of a team. San Franciso.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. NY: Harper.

- London, T. (2016). The base of the pyramid promise: Building businesses with impact and scale. Stanford University Press.

- Mayo, P. (1999). Gramsci, Freire and adult education: Possibilities for transformative action. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37.

- Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. London: W.

- Piketty, T. (2015). The economics of inequality. Harvard University Press.

- Prahalad, C.K. (2009). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, revised and updated 5th anniversary edition: Eradicating poverty through profits. FT Press.

- Schein, E.H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychological Association.

- Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York.

- Schwab, K. (2016). The fourth industrial revolution (World Economic Forum, Geneva).

- Smith, A. (1977). The wealth of nations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Stanford Social Innovation Review. (2016). The future of social impact education in business schools and beyond. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/the_future_of_social_impact_education_in_business_schools_and_beyond

- The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles

- Weber, M. (2013). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Routledge.

- Yunus, M. (2010). Building social business: The new kind of capitalism that serves humanity's most pressing needs.Public Affairs.