Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4

Curbing Unfair-Dismissal of Workers in Nigeria: What Lessons from Other Countries?

Andrew Ejovwo Abuza, Delta State University

Kingsley Omote Mrabure, Delta State University

Citation Information: Abuza, A.E., & Mrabure, K.O. (2022). Curbing unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria: What lessons from other countries? Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(4), 1-18.

Abstract

The 1999 Nigerian Constitution bestows on the National Industrial Court of Nigeria (NICN) exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine labour disputes relating to or connected with unfair labour practices, including unfair dismissal. There is, however, no general statutory right, in explicit terms, accorded to workers under the Nigerian Labour Law, not to be unfairly dismissed and to claim compensation, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair dismissal. This paper reviews the practice of unfair dismissal of workers in Nigeria. The research methodology utilised by the author is basically doctrinal analysis of relevant primary and secondary sources. The paper finds that the unfair dismissal of workers in Nigeria is contrary to the United Nations (UN) International Labour Organisation (ILO) Termination of Employment Convention 158 of 1982 (Convention 158) as well as international human rights’ norms or treaties. The paper suggests that Nigeria should enact a Labour Rights Act that would accord to workers, in explicit terms, the rights not to be unfairly dismissed and to claim compensation, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair dismissal in line with the practice in other countries, including the United Kingdom (UK) and Kenya.

Keywords

Unfair-dismissal, Unfair Labour Practice, 1999 Nigerian Constitution, Constitution (Third Alteration) Act 2010, Employer, Worker, Re-instatement, Re-employment, Nigeria.

Introduction

The general rule under the Nigerian Labour Law, governed significantly by the commonlaw, is that an employer in a mere master and servant relationship can terminate the contract of employment with an employee of any grade or level for good or bad reason or for no reason at all and contrary to the terms and conditions of the employee's contract of employment or the right to a fair hearing, guaranteed under the common-law and the Nigerian Constitution (Law, 2001). The entire employee is entitled to be damages for wrongful dismissal. The damages is the amount he would have earned over the period of a proper notice to terminate the contract of employment or the amount payable in lieu of a proper notice to terminate the same (Law, 2018).

The motive of the employer in terminating the contract of employment with the employee by giving a notice of termination is not relevant. Motive is a reason for doing something (Phillips, 2010). Put differently, motive is the hidden or real reason which made a party to terminate the contract of employment.

Often times, the employer decides to terminate his employee's appointment by giving notice of termination because of some hidden reasons, such as the active involvement of the employee in trade union activities. Where such is the real reason why the employee's appointment was terminated, it can be said to be a case of unfair dismissal for which the court should intervene to invalidate such a termination of employment. It is an open secret that many Nigerian workers have been victims of unfair dismissal, due to their participation in union activities. A good case is that of COB Eche vs State Education Commission and Another, where the plaintiff was dismissed from the Anambra State Public Service on the ground that he took part in a strike by teachers in the State.

It is disappointing that the Nigerian Labour Law does not provide, in explicit terms, for general statutory rights of an employee not to be unfairly dismissed and to claim compensation, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair dismissal as well as the circumstances where a dismissal may be considered to be unfair. The National Assembly of Nigeria (NAN) is to blame for this, as none of its enactments, including the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (Nigerian Legislation, 1999), as amended provides for general statutory rights of an employee not to be unfairly dismissed and to claim compensation, re-instatement and reemployment for unfair dismissal as well as circumstances where a dismissal may be considered unfair. These are the gaps this paper or research aims to address. Put in another words, the gaps above constitute the rationale behind conducting this research. A point to make is that these lacunae in Nigeria’s laws would not augur well for the system of administration of justice in the industrial sub-sector of Nigeria’s political economy, as it is prone to abuse as has been the case, for example, since the coming into force of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution. The case of Godwin Okosi Omoudu vs Aize Obayan and Another is a typical example. In the case, the second defendant-university terminated the claimant’s appointment, in breach of the contract of employment between the parties, as he was not paid one month’s salary in lieu of notice before or contemporaneously with the termination as enunciated under the said contract of employment and for an unfounded reason.

Needless to mention the planned five-days warning strike by the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) as well as Trade Union Congress (TUC) and their affiliates in Kaduna State between 16 and 19 May 2021 to reverse the termination of the employment of over 7, 000 civil servants in Kaduna State on the ground of redundancy without following the due process, having not given notice to the workers and their unions as well as paid severance package as encapsulated under section 20 of the Labour Act (Labour Act, 2004). This is a clear case of unfair-dismissal of workers by their employer that is the Kaduna State government (The Guardian, 2021). The strike paralysed economic activities of the State for the days it lasted. The strike was, however, suspended on 19 May 2021 to pave way for a reconciliatory meeting on 20 May 2021 at the instance of the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). At the end of the meeting, a memorandum of understanding was signed by both the State government and the NLC (El-Rufai, 2021). Despite this agreement, the Kaduna State government continued with laying-off workers in the State, as announced before the commencement of the strike. This prompted the NLC to write to President Muhammadu Buhari, threatening to resume the suspended strike in Kaduna. Meanwhile, Governor Nasir El-Rufai of Kaduna State, however, says there is no going back on right sizing of the State’s work force. According to His Excellency, over 90% of the State’s Federal Allocation is currently being spent on civil servants.

Of course, the practice in Nigeria contrasts with the practice in other countries like the UK, Canada, Ghana, South Africa and Kenya. In the UK, for instance, section 94(1) of the Employment Rights Act (ERA) 1996 specifically provides for the right of the employee not to be unfairly dismissed. While sections 95, 99, 100, 104A, 104C, 105(1), (3) and (7A) of the ERA 1996 contain circumstances where a termination of employment can be regarded to be unfair. Again, the remedies of interim relief, compensation, re-instatement or re-engagement are available to an employee who is unfairly dismissed in the UK.

A relevant question to ask at this juncture is: is the unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria lawful? Another relevant question is: are there lessons from other countries? A further relevant question is: should there not be statutory rights, in explicit terms, accorded to Nigerian workers not to be unfairly dismissed and to claim the reliefs of compensation, re-instatement and reemployment for unfair-dismissal in line with the practice in other countries? These questions form the basis or foundation of this paper.

The purpose of this paper is to review the practice of unfair dismissal of workers in Nigeria. It gives the meaning of employee, employer, unfair-dismissal, re-instatement and reemployment or re-engagement. It gives a brief history of the practice of unfair-dismissal in Nigeria. It analyses applicable laws, including the Nigerian Constitution and case-law on the practice of unfair-dismissal of workers under the Nigerian Labour Law. It highlights the lessons or take-away from other countries. It takes the position that the unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria is unlawful, unconstitutional and contrary to the Convention 158 as well as international human rights’ norms or treaties and offers suggestions, which, if implemented, could curb the problem of unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria.

Conceptual Framework

The word employee is a key-word in this paper. Section 48(1) of the Trade Disputes Act 2004 defines a worker as:

“Any employee, that is any member of the public service of the Federation or of a State or any individual other than a member of any such public service who has entered into or works under a contract with an employer, whether the contract is for manual labour, clerical work or is otherwise expressed or implied, oral or in writing and whether it is a contract personally to execute any work or labour or a contract of apprenticeship.”

The foregoing definition can be vilified. To be precise, it includes as a worker any person under a contract personally to undertake any work or labour that is an independent contractor and an apprenticeship contract. These persons cannot be regarded to be engaged under a contract of service so as to call them workers (Abuza, 2013).

Anyhow, a worker, irrespective of his grade, qualifies as an employee within the meaning of a worker in the foregoing definition.

On the other hand, an employer, another key-word in this paper, means:

“Any person who has entered into a contract of employment to employ any other person as a worker either for himself or for the service of any other person and includes the agent, manager or factor of that first mentioned person and the personal representative of a deceased employer.”

The employer of a worker would include a corporate organisation or unincorporated organisation, an individual, the local Government Council, the State Local Government Service Commission and the Civil Service Commissions of both the Federal and State governments.

Unfair-dismissal is another key-word in this paper. It is, also, known as unfairtermination or unjust-dismissal. It is part of unfair labour practice. Unfair-dismissal means the termination of a contract of employment bereft of a valid reason or good cause or fair procedure or both. Another key-word in this paper is re-instatement. It means to go back to a person's job. Re-instatement is a remedy that is only granted in Nigeria in favour of an employee whose contract of employment is with statutory flavour or protected by statute. Lastly, re-employment is another key-word in this paper. Re-employment or re-engagement, as it is sometimes called, means that the worker gets his job back, but starts as a new worker.

Brief History of the Practice of Unfair-Dismissal in Nigeria

In this segment, the discussion shows that the practice of unfair-dismissal in Nigeria dates back to the period when Nigeria was under the colonial rule of Britain.

What is called Nigeria today came into existence on 1 January 1914. This followed the amalgamation of the Colony of Lagos and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria as well as the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria by Lord Fredrick Lugard, the person whom the British colonial master of Nigeria appointed the first Governor-General of the country (Abuza, 2016 & 2020).

The authors cannot state with precision how and when the unfair-dismissal practice commenced in Nigeria. Nevertheless, it is crystal clear that the practice of unfair-dismissal started with the introduction of wage employment during the colonial period of Nigeria.

It is note-worthy to state that Nigeria was accorded independence from the UK on 1 October 1960. The country became a Republic in October 1963. Over the period between when Nigeria came into being and today many Nigerian workers have suffered from the practice of unfair dismissal. A typical example is that of the Eche case. Unfortunately, some ordinary courts in Nigeria have refused to accord the Nigerian worker the right to sue for unfair dismissal and claim reliefs such as compensation or damages, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair dismissal. Of course, a notable case on the matter is Samson Babatunde Olarewaju vs Afribank Public Limited Company, where the Supreme Court of Nigeria held that an employer in a mere master and servant contract of employment can terminate the contract at any time and for any reason or no reason at all. The position of the apex Court in Nigeria is hinged on the commonlaw.

Notwithstanding the provisions above, the practice of unfair dismissal has continued unabated in Nigeria.

Analysis of Case-law on the Practice of Unfair-Dismissal of Workers under the Nigerian Labour Law: The Approach of the Ordinary Courts

The ordinary courts in Nigeria have discussed the practice of unfair-dismissal of workers in many cases. A discussion on a few selected cases would suffice in this section. One significant case is Babatunde Ajayi vs Texaco Nigeria Limited. In the case, the appellant/plaintiff was employed on 7 March 1978, as Operations Manager by the first respondent/defendant-company a post which is permanent and pensionable. The second respondent/defendant was the Managing Director of the first respondent/defendant-company. While the third respondent/defendant was the General Manager of the first respondent/defendant-company. By a letter dated 1 February 1979, the second respondent/defendant directed the appellant/plaintiff to proceed on leave on the ground that his future relationship with the first respondent/defendant-company was under review. By another letter dated 23 March 1979, the second respondent/defendant invited the appellant/plaintiff to see him between 2 and 4 pm on that day. When the appellant/plaintiff went to see the second respondent/defendant, he was asked in the presence of the third respondent/defendant to tender his resignation of appointment, as Operations Manager to the first respondent/defendant-company. He was given up to 26 March 1979 to hand-over his letter of resignation, otherwise he would be dismissed from employment. The appellant/plaintiff refused to resign as requested by the second respondent/defendant. On his failure to resign as requested, the second and third respondents/defendants, pursuant to Exhibit D1- Employee's Handbook of the first respondent/defendant-company, terminated the employment of the appellant/plaintiff for working against the first respondent/defendant-company. Instead of giving the appellant/plaintiff one month's notice of termination or paying the same one month's salary in lieu of one month’s notice of termination, the second and third respondents/defendants paid the same three months salary in lieu of notice of termination and gave the same all his entitlements.

The appellant/plaintiff instituted a suit in the High Court of Lagos State, Lagos claiming against the respondents/defendants-(1) a declaration that:(a) the appellant/plaintiff was the Operations Manager of the first respondent/defendant-company under a contract of employment; (b) any breach of the said contract of employment between the appellant/plaintiff and the first respondent/defendant-company is illegal, invalid, ultra vires, null and void and of no effect; (2) any injunction restraining the first respondent/defendant-company by itself, its servants and / or agents or otherwise from committing a breach of the said contract of employment existing between the appellant/plaintiff and the first respondent/defendant-company or in any way interfering with the appellant/plaintiff in the performance of his duties as Operations Manager. In the alternative, the appellant/plaintiff claimed against the first respondent/defendant-company the sum of 634, 833 naira (N) as special and general damages for anticipatory breach of contract. The appellant/plaintiff argued that in terminating his contract of employment, the second and third respondents/defendants were not acting in the interest of the first respondent/defendantcompany but solely for their own selfish, irrelevant and improper motive. The trial High Court, Olanrewaju Bada, in its judgment delivered on 2 November 1979 stated that in the circumstances, I cannot make the declaration sought. In so far as a declaration cannot be made, an order for injunction, in the circumstances cannot be made. His Lordship, however, held that the threatened termination of the appellant/plaintiff’s appointment was unlawful. The trial High Court granted the alternative claim because the Court found the termination of appellant/plaintiff’s contract of employment malicious.

Being dis-satisfied with the judgment of the Court of Appeal, the appellant/plaintiff appealed to the Supreme Court of Nigeria. Justice Andrews Otutu Obaseki JSC, delivering the leading judgment of the Supreme Court of Nigeria on 12 September 1987 with which the other four justices of the Court concurred, dismissed the appeal of the appellant/plaintiff and affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeal. His Lordship stated thus:

“Where in a contract of employment there exist a right to terminate the contract given to either party, the validity of the exercise of their right cannot be vitiated by the existence of malice or improper motive. It is not the law that motive vitiates the validity of the exercise of a right to terminate validly an employment of the employee. There must be other considerations. The exercise is totally independent of the motive that prompted the exercise (Law, 1993).”

The authors take the position that the decision of the Supreme Court of Nigeria in the Ajayi case is not correct and, thus, unacceptable. It is argued that a termination of employment that contains ingredients of unfairness such as being ill-motivated or as a result of improper motive or bad or invalid reason like a worker’s participation in a strike is unfair or unjust and Court ought to intervene and invalidate the same. In the Eche case, Araka, CJ of the Anambra State High Court of Justice invalidated the dismissal of the plaintiff by the Anambra State Public Service Commission on ground of participation in a teacher’s strike. The Court seemed to have taken this stance because it considered the dismissal to be ill-motivated or based on a bad or invalid reason.

Another note-worthy case in point is Samson Babatunde Olarewaju vs Afribank Public Limited Company. In the case, the appellant/plaintiff was a Deputy-Manager of the respondent/defendant-company. He was suspended from work on some allegations of fraud and embezzlement of money as well as sundry allegations. He later appeared before the Senior Staff Disciplinary Committee of the respondent/defendant-company which tried him of the foregoing allegations. The appellant/plaintiff filed a suit in the High Court of Bornu State, Maiduguri challenging his summary-dismissal from employment by the respondent/defendant-company. The trial High Court held that the summary-dismissal was wrongful on the ground that the appellant/plaintiff was not first arraigned before a court of law to have his guilt on the offences alleged against the same established. It declared the summary-dismissal a nullity and ordered the immediate re-instatement of the appellant/plaintiff.

Being aggrieved by the judgment of the trial High Court, the respondent/defendantcompany appealed to the Court of Appeal which set-aside the judgment and order of the trial High Court. His Lordship pointed out that the appellant/plaintiff had a mere master and servant relationship with the respondent/defendant-company. Justice Katsina-Alu declared that:

“In a master and servant class of employment, the master is under no obligation to give reasons for terminating the appointment of his servant. The master can terminate the contract with the servant at any time and for any reason or no reason. In the instant case, no reason was given for the dismissal of the appellant.”

His Lordship held thus:

“In a pure case of master and servant, a servant's appointment can lawfully be terminated without first telling him what is alleged against him and hearing his defence or explanation. Similarly, a servant in this class of employment can lawfully be dismissed without observing the principles of natural justice.”

Furthermore, it was held by Justice Katsina-Alu that it was not necessary under section 33 of the 1979 Nigerian Constitution (now section 36 of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution) that before an employer can summarily dismiss his employee under the common law; the employee must be arraigned and tried before a court of law where the gross misconduct borders on criminality. In His Lordship’s view, where the employer’s Disciplinary Committee had found the employee guilty of gross misconduct bordering on criminality, the employer can either cause the same to be prosecuted in the court of law or summarily dismiss him from employment.

Lastly, Justice Katsina-Alu held as follows:

“Where a master terminates the contract with the servant in a manner not warranted by the contract, he must pay damages for breach of contract. The remedy is damages. The Court cannot compel an unwilling employer to re-instate a servant he has dismissed. The exception is in case where the employment is specially protected by statute. In such case, the employee who is unlawfully dismissed may be re-instated to his position.”

It is crystal clear from the foregoing decisions of the Supreme Court of Nigeria and the other ordinary courts in Nigeria that they are not prepared to accord an employee under a mere master and servant relationship the right to sue for unfair dismissal or to claim re-instatement or re-employment for unfair-dismissal. Their stance is hinged on the position under the commonlaw.

The authors take the position that the decision of the Supreme Court of Nigeria in the Olarewaju case is not correct and, thus, unacceptable for the following reasons. First, the apex Court in the Olarewaju case had suggested that the master is under no obligation to give reasons for the summary-dismissal of the servant. This is not correct, as in a contract of employment, whether a mere master and servant contract of employment or contract of employment protected by statute, reasons for the summary-dismissal of the servant must be advanced (Abuza, 2017). The courts, therefore, maintain that reasons for the summary-dismissal of the servant must be advanced by the master who said reasons must be justified by the master; otherwise the summary-dismissal would not be permitted to stand. In addition to this, the courts of law insist that where an employer pleads that an employee was dismissed from his job on account of a specific misconduct, the dismissal cannot be justified in the absence of adequate opportunity being given to him to explain, justify or else defend the misconduct that is alleged (Law, 2014).

Second, the decision of the apex Court in the Olarewaju case is not in accord with its earlier decision in Ewaremi vs African Continental Bank Limited, where it upheld the decision of the trial High Court which ordered the re-instatement of a company employee in a pure master and servant relationship on account that the purported dismissal of the appellant/plaintiff from the service of the respondent/defendant-company was null and void. Nigeria should borrow a leaf from other countries. For instance, in the Indian case of Provisional Transport Services vs State Industrial Court, the Supreme Court of India (per Nagpur Das Gupta J) declared that an industrial court would invalidate a dismissal of a worker and order re-instatement of the same where his dismissal was done without a fair enquiry.

Third, the decision of the apex Court in the Olarewaju case is contrary to section 36(4) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended. It states as follows:

“Whenever any person is charged with a criminal offence, he shall, unless the charge is withdrawn, be entitled to a fair hearing in public within a reasonable time by a court or tribunal.”

The apex Court had in previous cases interpreted the foregoing provisions to mean that when a Nigerian is alleged to have committed an offence he must be brought before the ordinary court for trial in order to establish his guilt and that no administrative panel can try the same for the offence alleged against him.

Arguably, the action of the apex Court in giving an employer or his disciplinary panel the option or right to try a servant who is a Nigerian on allegation of committing an offence is tantamount to a usurpation of the court’s duty for the benefit of a master or his disciplinary panel and depriving a Nigerian servant the protection accorded by section 36(4) of the 1999 Constitution, as amended. It is argued that no person in Nigeria should be permitted to usurp the jurisdiction and authority of the court of law in the country under any pretext or guise whatsoever.

Fourth, the Supreme Court can be vilified for taking the stance in the Olarewaju case that a master in a mere master and servant relationship can terminate the contract of employment for any reason or no reason at all. It is contended that a termination of an employment contract bereft of a valid reason is invalid or wrongful, being contrary to the Convention 158. To be specific, article 4 of the Convention states that:

“The employment of a worker shall not be terminated unless there is a valid reason for such termination connected with the capacity or conduct of the worker or based on the operational requirements of the undertaking, establishment or service.”

Articles 5 and 6 of the Convention above list matters which cannot constitute valid reasons for termination of employment. These matters are: membership of a trade union or participation in trade union activities outside working hours or with the consent of the employer within working hours; seeking office as, or acting, as having acted in the capacity of, a workers’ representative, the filing of a complaint or the participation in proceedings against an employer involving alleged contravention of laws or regulations or recourse to competent administrative bodies; race, colour, sex, marital status, family responsibilities, pregnancy, religion, political opinion, national extraction or social origin; absence from job during maternity leave; and temporary absence from job as a result of illness or injury.

It is argued that the Convention 158 has no force of law in Nigeria and, therefore, cannot be applied by the NICN in labour dispute resolution, having not been ratified by Nigeria. As disclosed already, the NICN is the Court that has exclusive original jurisdiction over all labour and employment-related matters. The country should sign and ratify the Convention 158 forthwith. As a member of the UN and ILO, it is obligated to apply the Convention 158. Needless to emphasise that the nation must show respect for international law and its treaty obligations, as enjoined by section 19(d) of the 1999 Nigeria Constitution, as amended.

Lastly, the apex Court can, also, be vilified for taking the position in the Olarewaju case that in a mere master and servant relationship, the servant’s employment can lawfully be terminated without first telling the same what is alleged against the same and hearing his defence or explanation as well as the servant in a mere master and servant relationship can lawfully be dismissed from employment without observing the rules of natural justice. Procedural fairness or these rules of natural justice are enunciated under the Convention 158, the common law and section 36(1) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended which guarantees the right to a fair hearing to all Nigerians. Thus, such dismissal from employment without adherence to procedural fairness or the rules of natural justice is void and a nullity for being inconsistent with, or a contravention of, procedural fairness or the rules of natural justice or the provisions of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as already disclosed. To be specific, article 7 of the Convention 158 embraces the principle of a fair hearing before dismissal or termination of employment by the employer. It declares as follows:

“The employment of a worker shall not be terminated before he is provided with an opportunity to defend himself against the allegation made, unless the employer cannot reasonably be expected to provide opportunity.”

A note-worthy case decided under the common law is R vs Chancellor, University of Cambridge. In the case, the University of Cambridge withdrew all the degrees it awarded in favour of its former student one Dr. Bentley without first hearing his explanation or defence. The Court of king’s Bench declared the action of the University unlawful. It issued an order of mandamus to the University of Cambridge requiring the restoration of Bentley’s Degrees of Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor and Doctor of Divinity of which he had been deprived by the University without a fair hearing. Fortesque of the Court of King’s Bench stated that even the Almighty God adhered to the rules of natural justice, as he did not punish Adam by driving him and his wife, Eve from the Biblical Garden of Eden for disobeying the same without first hearing him. It is a general principle settled by cases that the breach of statute or natural justice is a nullity. Good enough, the Supreme Court of Nigeria in Olatunbosun vs NISER Council a case in point, held that procedural fairness was acclaimed as a principle of divine justice with its origin in the Biblical Garden of Eden.

An important point to bear in mind is that the approach of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended, as could be discerned from its section 36(1) is in alignment with the position under international instruments. For instance, the Charter of the United Nations 1945 guarantees the right to a fair hearing. Also, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) 1948 guarantees the right to a fair hearing and other fundamental rights in its articles 3 to 20. Admittedly, the UDHR is a soft-law agreement and not a treaty itself and in this way not legallybinding on member-States of the UN, including Nigeria. Regardless, it has become customary international law that has been embraced globally in protecting human rights.

Additionally, the African Union (AU) African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) 1981 guarantees to every person, including a worker the fundamental right to be heard in its article 7. The African Charter has not only been signed and ratified by Nigeria but has equally been made a part of national law, as enjoined by the provisions of the same and section 12(1) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution. In Sanni Abacha vs Gani Fawehinmi, the apex Court in Nigeria held that since the ACHPR had been incorporated into Nigerian Law, it enjoyed a status greater than a mere international instrument and the same was part of the Nigerian body of laws.

Furthermore, the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) 1966 guarantees to every person, including a worker the fundamental right to a fair hearing in its article 14(1). It has been postulated that the ICCPR now has the effect of a domesticated enactment, as required under section 12(1) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended and, therefore, has the force of law in Nigeria, since the ICCPR guarantees labour rights to workers in its article 22(1) and has been ratified by the nation.

Again, the Arab Charter on Human Rights (ACHR) 2004 guarantees to every person, including a worker the right to legal remedy in its article 9 and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) 1953 guarantees to every person, including a worker the fundamental right to a fair and public hearing in its article 6. While the American Convention on Human Rights (AMCHR) 1969 guarantees to every person, including a worker the fundamental right to a fair hearing in its article 8. It should be noted, however, that Nigeria is not obligated to apply the provisions of the ACHR, ECHR and AMCHR above, as the country is not a member-State of the Council of the League of Arab States, Council of Europe and Organisation of American States, as well as State-Party to the ACHR, ECHR and AMCHR.

It is wise to argue that as a member of the UN and AU as well as a State-Party to the ACHPR and ICCPR, Nigeria is obligated to apply the provisions of the Charter of the UN, ICCPR and ACHPR. The country, in this connection, must demonstrate respect for international law as well as its treaty obligations, as enjoined by section 19(d) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended.

Regarding the right to a fair hearing guaranteed to citizens of Nigeria under section 36(1) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended the Nigerian Court of Appeal (per Helen Moronkeji Ogunwumiju JCA) held in Nosa Akintola Okungbowa and Six Others vs Governor of Edo State and Eight Others, that fair hearing is a constitutional and a fundamental right encapsulated in the Nigerian Constitution which cannot be waived or unjustly denied to a Nigerian, including a worker, and that a breach of the same in any proceedings nullified the whole proceedings. Also, the Supreme Court of Nigeria (per Amiru Sanusi JSC) held in James Avre vs Nigeria Postal Service that the right to a fair hearing is such an important, radical and protective right, that the courts of law put-up every effort to protect the same. It went further to declare that when an employee is accused by his employer of committing any act of misconduct, he must be accorded the opportunity to explain and give his reason, if any, for committing such misconduct.

With respect to fundamental rights generally, the Nigerian Court of Appeal (per Abdu Aboki JCA) held in Mallam Abdullah Hassan and Four Others vs Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and three others, that:

1. Fundamental rights are rights without which neither liberty nor justice would exist;

2. Fundamental rights stood above the ordinary law of the land and in fact constituted a primary condition to civilised existence;

3. It was the duty of the court, including the Supreme Court of Nigeria to protect these fundamental rights.

The words of the Nigerian Court of Appeal (per Obande Festus Ogbuinya JCA) in Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps and Six Others vs Frank Oko are apt. According to the Court:

1. Fundamental rights are rights attaching to man as a man because of his humanity;

2. Fundamental rights fell within the perimeter of species of rights and stood on top of the pyramid of laws and other positive rights;

3. Fundamental rights constituted a primary condition for a civilised existence;

4. Due to fundamental rights’ kingly position in the firmament of human rights, section 46 of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended allocated to every Nigerian whose fundamental right was or had been harmed, even quiatimet, to approach the Federal High Court or State High Court to prosecute his complaint and obtain redress.

A noteworthy point to make is that due cognisance must be accorded to the import of the provisions of Chapter Four of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended in which section 36(1) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended is a part. In actuality, they are sacrosanct. Should any provision require amendment, the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended provides for a tedious and challenging procedure in section 9(3). The country, in this light, must apply, and show respect for, the Constitution. It is important to bear in mind that in Nigeria the provisions of the Constitution are supreme and binding on all persons as well as authorities throughout the Federal Republic of Nigeria, including the Supreme Court of Nigeria.

In the final analysis, it is argued that the decision of the Supreme Court in the Olarewaju case on the matter is null and void. The argument is fortified by the decision of the apex Court in Attorney General of Abia State vs Attorney-General of the Federation. Perhaps, the Justices of the Supreme Court of Nigeria would have come to a different conclusion if they had applied their minds to the foregoing points.

The Approach of the National Industrial Court of Nigeria

Good enough, the NICN seems to have departed from the old traditional or common-law position on unfair dismissal, owing to its expanded jurisdiction under the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended by the CTAA 2010. To cut matters short, the NICN now has exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine all labour and employment-related disputes, including disputes relating to or connected with unfair labour practice or dismissal

According to section 254 C (6) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended by the CTAA 2010 an appeal shall lie from the decision of the NICN in criminal causes and matters, as stated in section 254C (5) above to the Court of Appeal as of right. Arguably, the decision of the Court of Appeal in any such criminal causes and matters shall be appealable to the Supreme Court of Nigeria.

A significant point to note is that based on the interpretation given to the provisions of section 243(2) and (3) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended by the CTAA 2010, by the Supreme Court of Nigeria in Skye Bank Public Limited Company vs Victor Iwu, all decisions of the NICN in the exercise of its civil jurisdiction are appealable to the Court of Appeal which said Court shall be the final court on labour disputes not touching on criminal causes or matters of which jurisdiction is bestowed on the NICN by virtue of section 254 C or any other Act of the National Assembly or any other law.

It is instructive to observe that the NICN considers unfair-dismissal to be an unfair labour practice. In short, the NICN is now prepared to declare invalid any determination of a contract of employment prompted by motive or reasons outside the recognised reasons for the termination of a contract of employment in article 4 of the Convention 158 or not in line with procedural fairness or the rules of natural justice or the right to a fair hearing in alignment with the Convention 158 and other international best practices in labour, employment as well as industrial relation matters. Also, it is now prepared to award appropriate remedies such as monetary compensation, re-instatement and re-employment, whether or not the contract of employment involved is a pure master and servant relationship. To be specific, the NICN warmly embraced the principle of unfair dismissal in arriving at its decision in Godwin Okosi Omoudu vs Aize Obayan and another (Kapsalis et al., 2019). In the case, the first defendant was a Professor and Vice-chancellor of the Covenant University, the second defendant. The NICN (per Adejumo J) held that the termination of the claimant’s appointment by the second defendant-university on 18 August 1981 was in contravention of the contract of employment between the parties and that the termination of the claimant’s appointment was, also, based on an unfounded reason, as disclosed before and was, therefore, wrongful.

His Lordship stated that it can never be just where an employer bereft of just and established cause express doubt about the integrity of an employee and based on this expression of doubt about the integrity of the employee goes ahead to terminate his contract employment in a way that did not allow for discussion and refusal. Justice Adejumo went further to assert that the law has moved from the narrow confines of the common-law in master and servant contract of service to a more pro-active approach which secures the rights of both parties to an employment contract. In this way, according to the learned Justice, the attention has shifted to protection of employees in matters of unfair labour practices in tune with the practice of other nations.

Justice Adejumo concluded that section 254C (1) (f) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended by the CTAA 2010 created an entirely new concept and right of unfair labour practice which is both alien to the common-law concept of master and servant relationship and the industrial relations jurisprudence hitherto- meaning before now existing in Nigeria. According to his Lordship, it was natural and expected that if this new right was violated there must be a remedy; otherwise the whole purpose of creating the right would be defeated. Justice Adejumo asserted further that if no specify remedy was created by the Nigerian Constitution, the NICN was duty-bound to look at the practice in other countries where the concept had been borrowed. The Court, in the view of His Lordship, was duty-bound to give section 254C (1) (f) above a broad interpretation and interpret the same as both accommodative of giving a right and imposing a remedy for its contravention.

Honourable Justice Adejumo granted the following reliefs in favour of the claimant:

1. The termination of claimant’s employment is declared wrongful;

2. The claimant is awarded one-month salary in lieu of notice of termination of his contract of employment;

3. The claimant is awarded five-months salaries as general damages;

4. The claimant is awarded the costs of N100, 000; and

5. The judgment sum shall attract 10% interest rate per annum, from the date of this judgment until the judgment debt is fully-liquidated.

The decision of the NICN above is commendable, being in line with the practice in other countries, including South Africa, Kenya, the UK, Canada and Ghana. Nonetheless, the Court can be criticised. Firstly, section 254C (1)(f) above does not stipulate in explicit terms the right of an employee not to be unfairly dismissed or right not to be subjected to unfair labour practice. Secondly, section 254C (1)(f) above or any other Nigerian statutory provision does not provide for the circumstances that would amount to unfair dismissal or any remedy for unfair dismissal or unfair labour practice. Lastly, contrary to the doctrine of separation of powers, His Lordship tried to make law by substituting his own words for the words used in the Nigerian Constitution in order to give them a meaning which suits the Court.

To sum-up on the issue of analysis of case-law on the practice of unfair-dismissal of workers under the Nigerian labour law, it is not out of context to emphasise that the unfairdismissal of workers in Nigeria is unlawful, unconstitutional and contrary to the Convention 158 as well as international human rights’ norms or treaties.

Discussion

What is of interest in this sub-heading is the discussion of the practices of unfairdismissal in selected countries and the result of the research. The relevant countries with regards to the practice of unfair-dismissal are discussed below:

South Africa

In South Africa a country practicing the common law, the Parliament has intervened by enacting the Labour Rights Act (LRA) 1995 to provide for a right of the employee not to be unfairly dismissed, circumstances where a termination of employment can be considered to be unfair, remedy of compensation, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair dismissal, and employees who can sue for unfair dismissal. With respect to the latter, employees of the National Defence Force, National Intelligence Agency, South African Secret Services, South African National Academy of Intelligence and Communications Security (COMSEC) cannot file a claim for unfair dismissal. It should be noted that in South Africa, the Labour Court is bestowed with jurisdiction to hear and determine labour disputes, including cases of unfair dismissal.

United Kingdom

In the UK a country practicing the common law, the Parliament has intervened by enacting the Employment Rights Act (ERA) 1996 to provide for a right of the employee not to be unfairly dismissed, circumstances where a termination of employment can be regarded to be unfair, remedy of interim relief, compensation, re-instatement or re-engagement for unfairdismissal and employees who can sue for unfair dismissal. Regarding the latter, it should be stressed that the UK imposes limitations on the exercise of the right to file a suit for unfairdismissal. To be precise, only employees who have worked for an employer for a period of at least two years have a right to file a claim for unfair-dismissal. There are exceptions for those persons who are dismissed automatically and those persons who are dismissed principally for a reason connected with political opinion or affiliation. Furthermore, the right to bring a complaint to an Employment Tribunal, which is conferred with jurisdiction to hear and determine labour disputes, including cases of unfair-dismissal, is not accorded to self-employed people, independent-contractors, members of the Armed forces or Police forces, unless the dismissal is connected with health and safety or whistleblowing.

Kenya

In Kenya a country practicing the common law, the Parliament has intervened by enacting the Employment Act (EA) 2007 to provide for a right of the employee not to be unfairly dismissed, circumstances where a termination of employment can be regarded to be unfair, remedy of compensation, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair-dismissal, and employees who can sue for unfair-dismissal. Regarding the latter, it should be emphasised that Kenyan law imposes limitations on the exercise of the right to file a claim for unfair-dismissal. To be specific, under the Kenyan law, only employees who have been continuously employed by their employers for a period of not less than 13 months immediately before the date of termination could sue for unfair-dismissal (Kyriakopoulos, 2012). In Kenya, it is the Employment and Labour Relations Court that is bestowed with jurisdiction to hear and determine labour disputes, including unfair dismissal.

Nigeria

In Nigeria a country practicing the common law, as disclosed already, the Parliament has intervened by enacting the CTAA 2010 to amend the 1999 Nigerian Constitution. Section 254 C(1)(f) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended by the CTAA 2010 gives the NICN exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine labour disputes, relating to or connected with unfair labour practice, including unfair dismissal. It has been indicated before that the provision above or any other Nigerian statutory provision does not stipulate in explicit terms the right of an employee not to be unfairly dismissed or right not to be subjected to unfair labour practice unlike the practice in other countries, including South Africa, the UK and Kenya. Also, the provision above or any other Nigerian statutory provision does not provide the remedies of compensation, re-instatement and re-employment for unfair labour practice or unfair dismissal unlike the practice in other countries, including South Africa, the UK and Kenya as disclosed before. Finally, the provision above or any other Nigerian statutory provision does not contain the circumstances that would amount to unfair dismissal unlike the practice in other countries, including South Africa, the UK and Kenya, as indicated already (LawNet, 2010).

It is glaring from the foregoing review of the practice of unfair dismissal of workers in Nigeria that some ordinary courts in Nigeria have not accorded Nigerian workers the right to sue for unfair dismissal. These courts have hinged their decisions on the position of employees in a mere master and servant relationship under the common-law.

It is observable that the unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria is unlawful and contrary to, among other international laws, the Convention 158 (Kyriakopoulos, 2011).

Also, it is observable that section 254C (1)(f) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended by the CTAA 2010 gives the NICN exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine claims on unfair labour practice, including unfair-dismissal. Regrettably, neither the Constitution above nor any other enactment in Nigeria provides for general statutory rights of an employee not to be unfairly dismissed by the employer and reliefs such as re-instatement, re-employment and compensation for unfair dismissal as well as circumstances where a termination of employment of an employee would be considered an unfair dismissal. Thus, the problem of unfair dismissal of workers in Nigeria has continued unabated. A typical example is the Omoudu case.

Furthermore, it is observable that in the UK, South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria, courts have been established to hear and determine disputes over unfair labour practice, including unfair dismissal, as disclosed before. The following Table 1 shows comparison on the court that has exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine disputes bordering on unfair labour practice, including unfair dismissal in the UK, South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria.

| Table 1 Courts that have Exclusive Jurisdiction to Handle Claims on Unfair Labour Practice, Including Unfair Dismissal in the Countries Covered by this Study | |

| Country | Court |

| UK | Employment Tribunal |

| South Africa | Labour Court |

| Kenya | Employment and Labour Relations Court |

| Nigeria | National Industrial Court of Nigeria |

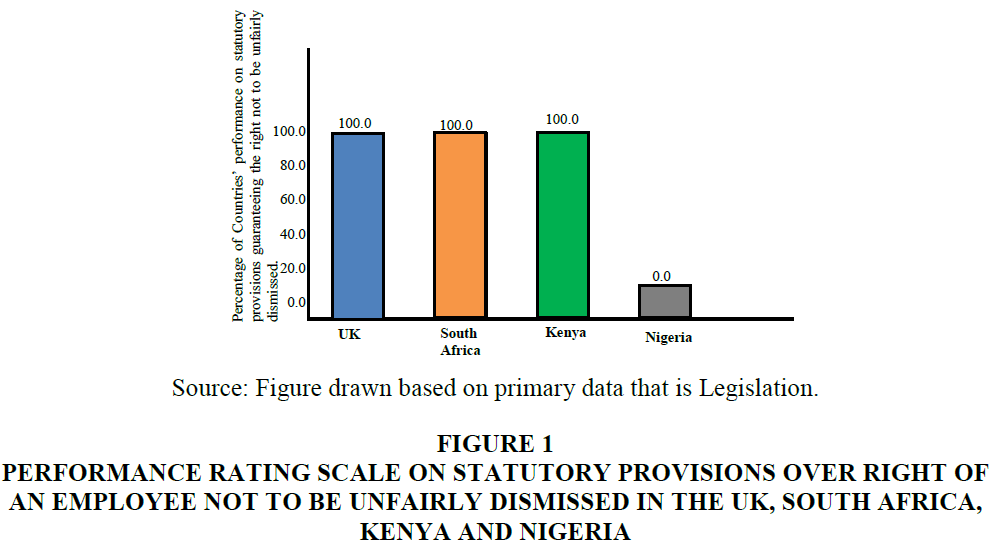

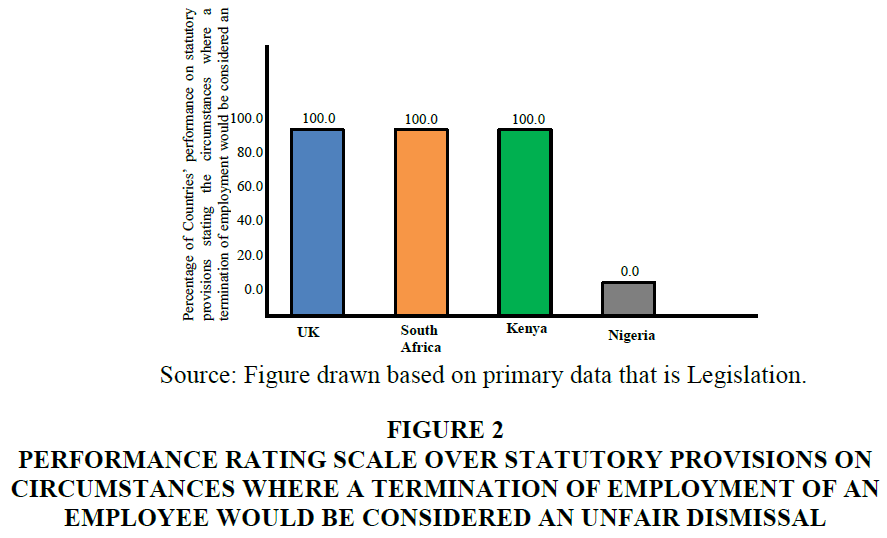

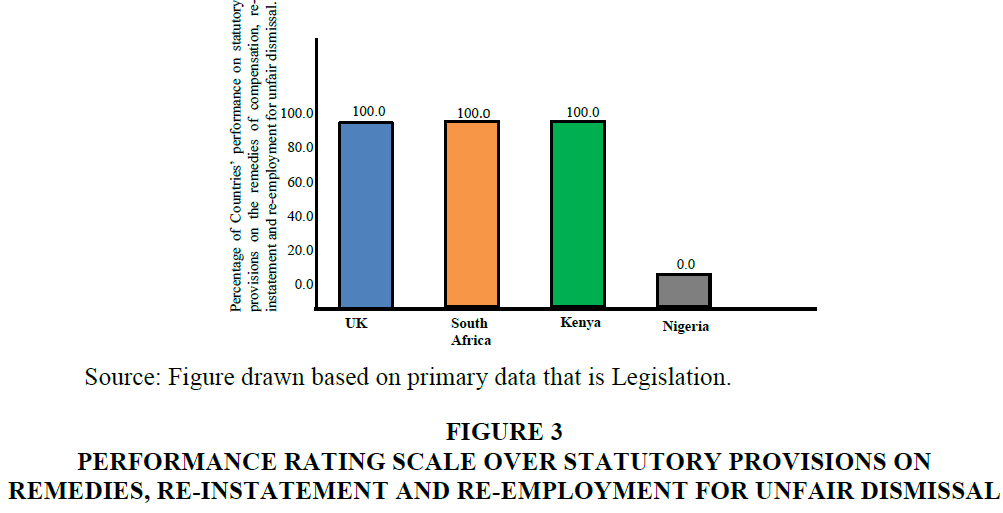

Again, it is observable that the Parliament in the UK, South Africa and Kenya, among other countries has intervened to provide for the right of the employee not to be unfairly dismissed by the employer, circumstances where a termination of employment of an employee would be considered an unfair dismissal, and remedies of compensation, re-instatement and reemployment for unfair dismissal (Chalikias et al., 2014). These developments are certainly commendable. They are, indeed, consistent with international law, including the Convention 158. The analysis above can be seen in the following Figure 1-3.

Figure 1 Performance Rating Scale on Statutory Provisions Over Right of an Employee not to be Unfairly Dismissed in the UK, South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria

Figure 2 Performance Rating Scale Over Statutory Provisions on Circumstances Where a Termination of Employment of an Employee would be Considered an Unfair Dismissal

Figure 3 Performance Rating Scale Over Statutory Provisions on Remedies, Re-Instatement and Re-Employment for Unfair Dismissal

The problem of unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria must be accorded the highest consideration it deserves by the FGN under the headship of President Muhammadu Buhari so that it is not accused of pretending on the issue of vesting in the NICN exclusive jurisdiction over labour disputes relating to unfair labour practices, including unfair-dismissal. A continuation of the problem of unfair-dismissal of workers in the country poses a grave danger to the industrial sub-sector of Nigeria’s political economy. It is already engendering industrial disharmony with capacity to stop economic growth and development. The authors wish to re-call the five-days warning strike by the NLC and TUC as well as their affiliates in Kaduna State, as disclosed before. Incessant strike by workers has capacity to impact negatively on the economy of Nigeria. This would undoubtedly discourage both local and international businessmen to invest their resources in the economy of Nigeria. Thus, President Buhari may not be able to accomplish fully the Change Agenda of the FGN for the all-round socio-economic development of the nation (Ogunniyi, 1991).

Recommendations

The problem of unfair dismissal of workers in Nigeria should be effectively addressed in Nigeria. In order to overcome the problem, the authors strongly recommend that:

“Nigeria should enact a new law to be known as the Labour Rights Act to provide for a right not to be unfairly dismissed and right to seek reliefs of re-instatement, re-employment and compensation for unfair-dismissal as well as circumstances where a termination of employment would be considered an unfair-dismissal. It’s in accord with the practice of other countries, including the UK, South Africa and Kenya, as disclosed before. A law on unfair-dismissal such as the proposed Labour Rights Act would take care of the problem above and give some protection to workers who may otherwise be rounded out of employment on account of their union activities and other invalid reasons for the termination of employment.”

Conclusion

This paper has reviewed the practice of unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria. It identified shortcomings in the various applicable laws and stated clearly that the practice of unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria is unlawful, unconstitutional and contrary to international human rights’ norms or treaties as well as the Convention 158. This paper, also, highlighted lessons or take away from other countries and made suggestions and recommendations, which, if carried-out, could effectively address or end the problem of unfair-dismissal of workers in Nigeria.

References

Abuza, A.E. (2013). Lifting of the ban on contracting-out of the check-off system in Nigeria: An analysis of the issues involved. The Banaras Law Journal, 42(1), 1-136.

Abuza, A.E. (2016). A reflection on the regulation of strikes in Nigeria. Commonwealth Law Bulletin, 42(1), 3-37.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Abuza, A.E. (2017). An examination of the power of removal of Secretaries of Private Companies in Nigeria. Journal of Comparative Law in Africa, 4(2), 34-76.

Abuza, A.E. (2020). A reflection on the issues involved in the exercise of the power of the attorney-general to enter a Nolle Prosequi under the 1999 constitution of Nigeria. Africa Journal of Comparative Constitutional Law, 85(2), 79–109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chalikias, M., Kyriakopoulos, G., Skordoulis, M., & Koniordos, M. (2014). Knowledge management for business processes: employees’ recruitment and human resources’ selection: A combined literature review and a case study. In Joint Conference on Knowledge-Based Software Engineering. Springer, Cham.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

El-Rufai. (2021). NLC petitions Buhari, threatens to resume suspended strike in Kaduna.

Kapsalis, V.C., Kyriakopoulos, G.L., & Aravossis, K.G. (2019). Investigation of ecosystem services and circular economy interactions under an inter-organizational framework. Energies, 12(9), 1734.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kyriakopoulos, G.L. (2011). The role of quality management for effective implementation of customer satisfaction, customer consultation and self-assessment, within service quality schemes: A review. African Journal of Business Management, 5(12), 4901-4915.

Kyriakopoulos, G.L. (2012). Half a century of management by objectives (MBO): A review. African Journal of Business Management, 6(5), 1772-1786.

Labour Act. (2004). Laws of the Federation of Nigeria Cap L 1 LFN 2004.

Law. (1993). Fakuade vs Obafemi Awolowo University teaching hospital complex management board 4 NWLR (Pt.291) 45, 58, SC. Nigeria.

Law. (2001). Samson Babatunde Olarewaju vs Afribank Nigeria public limited company. Supreme Court (SC), Nigeria.

Law. (2014). James Avre vs Nigeria postal service 46 NLLR (Pt. 147) 1, 10, CA. Nigeria.

Law. (2018). Abalogu v Shell petroleum development company of Nigeria Ltd. Nigeria.

LawNet. (2010). Sri Lanka chamber of small industry (incorporation) (amendment) Act, No. 1 of 2010.

Nigerian Legislation. (1999). Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 Cap C 23 LFN 2004.

Ogunniyi, O. (1991). Nigerian labour and employment law in perspective.

Phillips, P. (2010). AS Hornsby's Oxford advanced learner's Dictionary: International students Edition. Oxford University Press.

The Guardian. (2021). NLC may escalate Kaduna strike to National Industrial action.

Received: 27-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-11390; Editor assigned: 01-Mar-2022, PreQC No. JLERI-22-11390(PQ); Reviewed: 15- Mar-2022, QC No. JLERI-22-11390; Revised: 31-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-11390(R); Published: 07-Apr-2022