Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 2S

Cybercrime regulation and Nigerian youths increasing involvement in internet fraud: Attacking the roots rather than the symptoms

Felix Emeakpore Eboibi, Niger Delta University

Omozue Moses Ogorugba, Delta State University

Citation Information: Eboibi, F.E., & Ogorugba, O.M. (2023). Cybercrime regulation and Nigerian youths increasing involvement in internet fraud: Attacking the roots rather than the symptoms. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 26(S2), 1-17.

Abstract

Despite the objective of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 to curtail cybercrimes, there seems to be no end in sight to Nigerian youths increasing involvement in domestic and international internet fraud. The scope of Nigerian youths' involvement has signalled a consistent and deliberate attack on foreign victims' finances and impact on the global economy. Furthermore, family ties of internet fraud perpetrators, the rise of cybercrime institutions and academies, lack of commensurate punishments have further worsened attempts to curtail internet fraud. In this regard, cybercrime investigators' implementation of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 through resort to arrests on intelligence reports and consequent prosecutions has had little impact on Nigerian youths' perpetuation of internet fraud. Consequently, the paper seeks to answer the research questions thus: What are the reasons for Nigerian youths increasing involvement in internet fraud? What can be done to attack the roots of internet fraud instead of the symptoms? The paper, amongst others, makes a case for a rejuvenated effort by the Nigerian and foreign governments to facilitate an end to unemployment of youths, extending internet fraud investigations and prosecution to parents of perpetrators“super internet fraudsters”and those involved in the training of these perpetrators.

Keywords

Cybercrime Regulation, Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2105, Nigerian Youths, Internet Fraud, Cybercrime Punishment.

Introduction

The growth and application of technology infrastructures in Nigeria and globally have seen the increasing involvement of Nigerians, especially Nigerian youths in cybercrimes domestically and internationally (Eboibi, 2020; Richards & Eboibi, 2021, Eboibi, 2018). Though devoid of any acceptable universal meaning, the concept of cybercrime connotes the application of technology infrastructures and computers as an instrument or target of a crime. This makes the cybercriminal liable to a legal punishment when found guilty of the act by a court of competent jurisdiction. Internet fraud is a variant of cybercrime, mainly because it is committed in cyberspace with computers and technology infrastructures instrumentality (Eboibi, 2020; Richards & Eboibi, 2021, Eboibi, 2018). It implies “The use of Internet services or software with Internet access to defraud victims or to otherwise take advantage of them” (FBI; Gillespie & Magor, 2019). The concept of cybercrime is mostly used to denote crimes perpetrated with the instrumentality of technology infrastructures and computers due to its exhaustive nature in accommodating such crimes (Richards & Eboibi, 2021). Internet fraud negatively impacts global online users, their emotions, finances and psychology (Aiezza, 2020). Recent developments show that Nigerian youths are involved in enormous international fraud schemes targeted mainly against overseas countries and victims, leading to massive financial losses ((U.S. Attorney’s Office, 2020; U.S. Attorney’s Office, 2021a; U.S. Attorney’s Office, 2021b; Eboibi, 2022). These acts affect the global economy by billions of dollars. For example, the 2021 Internet Crime Report notes that the total global loss due to internet scams in the past five years is $18.7 Billion (FBI, Internet Crime Report, 2021). The increasing involvement of Nigerian youths in global internet fraud implies that they would continue to contribute to the impacts mentioned above on internet users unless the suggestions in this work are implemented without delay. This has also questioned the effectiveness of cybercrime regulation in Nigeria and the enactment of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 and its implementation against the acts of internet fraudsters by the Government of Nigeria (Eboibi, 2018).

Internet fraud in Nigeria is called “Yahoo”, while the act is said to be perpetrated by “yahoo boys” who are mostly Nigerian youths. The nature and immediate successes and financial gains that accrue to these internet fraudsters upon exploiting the internet show that the Nigerian cybercrime regulation has done little or nothing to curtail the perpetration of cybercrimes. Their public show of wealth and extravagant lifestyles both online and in the society, in terms of gigantic houses, expensive cars and properties they acquire generally influence other Nigerians and African youths to patronise cyber criminality, which further increases the youth's involvement. Moreover, the societal respect and positions they are accorded due to their proceeds of internet fraud make other youths see them as role models, aspiring to be like them (Richards & Eboibi, 2021). The preceding raises the question: What are the reasons for Nigerian youths increasing involvement in internet fraud? What can be done to attack the roots of internet fraud instead of the symptoms? This paper primarily argues that the quest by the Nigerian Government to eradicate cybercrime through its enactment of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 and its implementation is merely a symptomatic attempt to curtail the menace of internet fraud being perpetrated by Nigerian youths. The Nigerian government and cybercrime institutions have arguably failed to address the root causes of Nigerian youths' increasing involvement in cybercrimes and internet fraud specifically.

Although there have been successful investigation and prosecution of internet fraudsters domestically and internationally, internet fraud still proliferates (Akanle and Shadare, 2020; Adejoh et al., 2019). Unemployment of Nigerian youths after graduation from higher institutions and the lack of infrastructural development arguably caused by the endemic corruption in the political and public sectors is a major contributing factor. Consequently, in order for most youths to survive the conditions they resort to internet fraud. This is further worsened by family ties and parents of Nigerian youths who desire better living standards for themselves and their wards to encourage them to learn the lucrative trade of internet fraud (Whitty, 2018; Brody et al., 2020). Some families conspire amongst themselves and aid the perpetration of the crime, with most of them going unpunished (Adejoh et al., 2019). This has become easier with the springing up of several cybercrime academies and training centers in different parts of Nigeria, where Nigerian youths are being trained to be sophisticated and professional in the art of internet fraud, especially against foreign victims (Oseghale, 2022).

In this regard, section one of this paper introduces the background to the research paper. It discusses the role of technology infrastructures and computers on the proliferation of internet fraud, its impacts on victims and the global economy, and the increasing role of Nigerian youths' involvement. Section two examines from a comparative perspective the scope of the cybercrime problem and Nigerian youths' involvement and its influence on the global financial downturn. Section three takes a critical look at the failure of the recent efforts put in place by the Nigerian Government to address the problem. Section four discloses that the recent efforts by the Nigerian Government at tackling cybercrimes are symptomatic and consequently suggests drastic measures that deal with the root causes of cybercrimes and internet fraud specifically. Conclusively, section five concludes the paper by drawing inferences from the discourse.

The Scope of the Cybercrime Problem and Youth Involvement

The Nigerian Government’s failure in its responsibilities toward the welfare of Nigerians accentuated by endemic corruption is arguably a motivating factor for Nigerian youths increasing involvement in cybercrimes, especially internet fraud. Monies meant for infrastructural development, job creation, and social well-being have been and are still being diverted by political and public officials, coupled with other corrupt activities. These have consequently significantly impacted the economy of Nigeria negatively and brought to a minimum Nigerians' standard of living and quality of life. Moreover, as part of measures to survive the inferior quality of life, economic hardship and low standard of living, some Nigerians, especially the youths, resorted to different kinds of fraudulent schemes, most times with the cooperation of additional Nigerians living in the United States of America and other developed and developing countries (Brody et al., 2020).

Whitty (2018) notes regarding West African youths' involvement in cybercrime, including Nigeria, thus: “Corruption is the root of all evil acts. The issue of embezzlement is also germane. Monies given out to officials to create infrastructural facilities and even jobs to people are diverted into personal purse. This serves as negative influence on people particularly the youths” ((Whitty, 2018; Brody et al., 2020). In a related development, Whitty further observed the negative impacts of these activities by political and public officials thus: “the deterioration of the region’s economy and the increased number of unemployed graduates has been a catalyst for cybercrimes. Students are skilled to commit these crimes, and if they foresee little opportunity for employment after their studies, might be tempted into acquiring money by employing their skills in illegal activities to gain money” (Whitty, 2018). In essence, the Nigerian Government’s quest to effectively eradicate the proliferation of cybercrimes by Nigerian youths is circumvented by its officials and the resultant increasing poverty nature of Nigerians (Hassan et al., 2012).

The Nigerian youth unemployment statistics buttresses the Nigerian youth's preference for the perpetration of cybercrimes and their increasing nature. As of December 2020 Nigerian youth unemployment rate is put at 53.40 per cent, a significant increase compared to the previous year, which was put at 40.80 percent. Worse still is the projection that at the end of 2022, the youth unemployment rate will reach 53 percent (Trending Economics, 2022). Recently, in a lecture presented by Akinwumi Adesina (President of the African Development Bank, AFDB) “Nigeria-A Country of Many Nations: A Quest for National Integration,” he lamented the increasing rate of joblessness or unemployment of Nigerian youths and how it has resulted to a source of discouragement, annoyance and restlessness to the Nigerian youths (Utomi, 2022).

As a sequel to the preceding, Nigerian youths' quest for survival has arguably seen most of them being increasingly involved in the perpetration of internet fraud, especially against foreign victims whose profitable exchange currency rate is a driving force. As Chude-Sokei (2011) notes, “Official statistics suggest that they bilk the United States of billions of dollars per annum and even more in the UK. Now that they have set their sights on China and India after a generation assaulting Singapore, Australia, Ukraine and everywhere else in the world, there is more for them to gain.” The recent Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud schemes such as romance fraud, Business Email Compromise (BEC) fraud, investment fraud, crypto currency fraud, advance fee fraud etc. against foreigners: Individuals, corporations and governments are copiously captured in several massive internet fraud activities in the United States of America with impact in other foreign countries (Eboibi, 2022).

In the United States of America v. Amechi Colvis Amuegbunam (2015), the defendant is a Nigerian youth of 30 years old who was granted US student visa. He was indicted and charged to court for conspiracy to commit Wire Fraud in the role he played in a BEC scheme with other co-conspirators against US companies that resulted in a loss of about 3.7milllion dollars. The court documents reveal that the defendant, between November 2013 and August 2015, conspired with others to send fraudulent emails to corporate organisations in the Northern District of Texas and other places whereby facts were misrepresented and consequently made the companies electronically send funds to them. He was subsequently sentenced to 46 months in US federal prison by US District Judge Ed Kinkeade and was mandated to restitute the victims of $615,555.12 in August 2017 (Case No. 3:15-cr-00411K; Department of Justice, 2015a; Department of Justice, 2017). The defendant’s involvement in internet fraud as a holder of US student visa is worrisome when viewed against the background of other Nigerian youths with similar US visas, especially with several Nigerian youths already studying in the US with roots and affiliations in Nigeria. The fear of proliferating cybercrime attacks against the US and other foreign countries by Nigerian youths with student visas is arguably heightened by the recent case of United States of America v Emmanuel Oluwatosin Kazeem, Oluwatobi Reuben Dehinbo, Lateef Aina Animawun, Oluwaseunara Temitope Osanyinbi and Oluwamuyiwa Abolad Olawoye and United States of America v Michael Oluwasegun Kazeem. The 1st defendant (Emmanuel Oluwatosin Kazeem) is a beneficiary of a US student visa. He masterminded one of the most significant cyber tax identity thefts in the history of the US, which resulted in more than $2 million US dollars loss against the US IRS with the help of his brothers and other co-conspirators in Nigeria. He was, however, charged to court and successfully prosecuted (United States District Court, District Court of Oregon, Medford Division; United States Attorney Office, 2017).

In the United States of America v. Perry Osagiede & 7 ors (2021) the eight defendants are Nigerian youths between the age bracket of 33 and 41, except the first defendant, who is 51 years old. They are members of a secret cult organisation, Neo Black Movement of Africa (Black Axe), Cape Town Zone, South Africa, indicted for conspiracy to commit wire fraud, wire fraud, identity theft, aggravated identity theft and money laundering. They conspired among themselves and others to perpetrate an extensive internet fraud through romance scams and advance-fee schemes against US citizens, which involved several millions of dollars between 2011 and 2021 (Case No. 3:21-cr-00392-MAS; Department of Justice, 2021f). The involvement of cult organisations in internet fraud, as Black Axe seem to have done here, presents a different dimension towards the escalating nature of cybercrime globally. Internet fraud perpetration has moved away from being individually based orchestrated crime to oath-taking cult organisations where internet fraud is now openly discussed as part of their membership and agenda. Membership of these organisations cutting across boundaries and nations, coupled with the sophistication, skills and professionalism in internet fraud by members who are predominantly youths, further complicates the quest to curtail the menace of internet fraud (Case No. 3:21-cr-00392-MAS; Department of Justice, 2021f).

In the United States of America vs. Chukwuemeka Onyegbula, aka Phillip Carter (2021), the defendant is a Nigerian, indicted for conspiracy to commit wire fraud, several counts involving wire fraud and aggravated identity theft. He conspired with his co-conspirators to steal personal identification information of US citizens which he used to file for fraudulent unemployment claims via electronic mails resulting in loss of millions of dollars in Washington, Arizona, California, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Ohio, Nevada, Rhode Island, Texas, and Wisconsin (Case No. 3:21-cr-05214-BHS; Department of Justice, 2021d). Moreover, several Nigerian youths have been indicted for their involvement in a colossal international internet fraud scheme involving millions of dollars in a 252 count charge in the “United States of America v. Valentine Iro & 79 others” (US District Court, Central District of California, 2019). The increasing nature of internet fraud and its impact above shows how heartless the perpetrators have become and, with no end in sight, implies that victims will continue to be left heartbroken, emotionally and psychologically traumatized and devastated financially (Department of Justice, 2021a). For instance, the Internet Complaint Centre noted in 2015 that the BEC scheme perpetrated by internet fraudsters affected over 7000 US-based businesses and over 1000 businesses based abroad with a total financial loss of approximate $747 million (Department of Justice, 2015b). However, the Internet Crime Report of 2021 shows about 19,954 BEC complaints/victims with an approximate loss of $2.4 billion (FBI, Internet Crime Report, 2021).

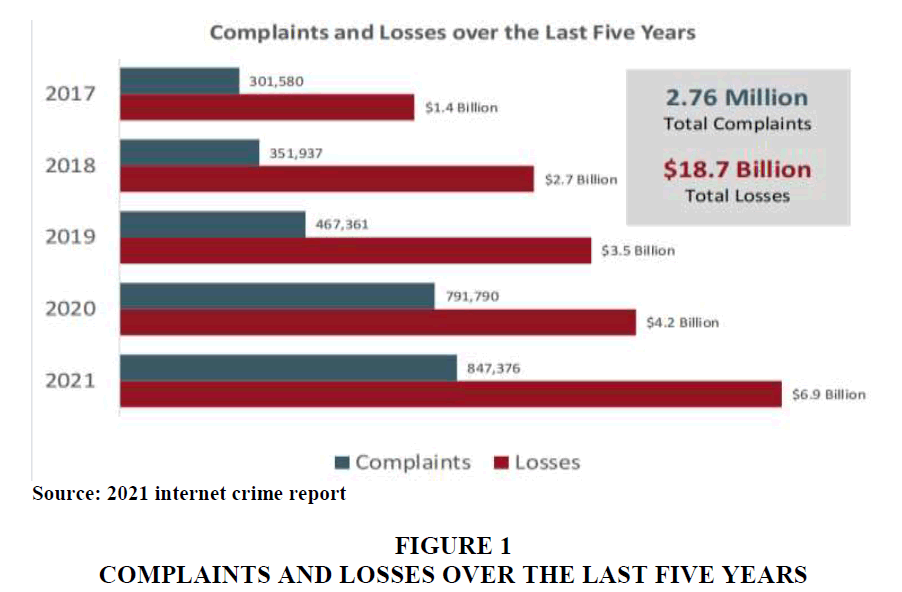

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission which is at the helm of the investigation and prosecution of internet fraud perpetrators in Nigeria, has alluded to Nigerian youths' widespread involvement in internet fraud. The EFCC has successfully prosecuted some Nigerian youths involved in internet fraud, especially against foreign victims. In the Federal Republic of Nigeria vs. James Emakhu (2019), the defendant in 2018 used a fake identity to chat with Miss Lucci Allion, a Polish woman, in an internet dating site with the fraudulent intent to collect from her and indeed obtained $2,000 contrary to section 22 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015. The defendant pleaded guilty to the charge and was sentenced to 2 months imprisonment and a fine of N 150,000 (One Hundred and Fifty Thousand Naira) (Charge No. FHC/B/25/c/2019). In the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Oseghale Thank God (A.K.A James Lee Chan, 2019), the defendant fraudulently impersonated the identity of one Richard Choi and sent his photograph through the internet to Susan Chan, an American woman, with the intent to collect money from her and indeed obtained the sum of N 7,000,000 (Seven Million Naira) from the victim, contrary to section 22 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015. The defendant pleaded guilty to the charge and was sentenced to six months imprisonment and a fine of N 1,000,000 (One Million Naira) (Charge No. FHC/B/25/c/2019). In the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Aluede Emmanuel (Alias Williams Alexandes, (2019), the defendant in an internet dating site fraudulently impersonated the identity of Williams’s Alexander, a US citizen to Miss Frida Estrada with the intent to collect money. The victim was indeed induced to part with several sums of money to the defendant. He pleaded guilty to the charge and was sentenced to 2 months imprisonment and a fine of N 150,000 (One Hundred and Fifty Thousand Naira) (Charge No. FHC/B/23c/2019). Moreover, based on the available information uploaded on the EFCC official website regarding activities of arrested and convicted perpetrators of internet fraud, arguably a total of 1,945 persons were arrested in 2021, most of whom were Nigerian youths, while 565 convictions were secured (EFCC, 2021h). In the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Aifuwa Courage Osasumwen (2021), Justice Taiwo O. Taiwo of the Federal High Court, Abuja, acknowledged Nigerian youths' widespread participation in internet fraud when she stated thus: “Given the prevalence of cybercrimes and echoing the fears of the current Chairman of the EFCC, if care is not taken, 70% percent of our youth may be termed ex-convicts and our society is doomed.” (Suit No: FHC/ABJ/CR/78/2021) The increasing participation of Nigerian youths in cybercrime has resulted in the global widespread of cybercrimes (internet scams) and financial devastation. Based on the 2021 Internet Crime Report, Cybercrime perpetration is on the yearly increase globally. It is illustrated (Figure 1), thus:

The report reveals that between 2017 and 2021, there were total cybercrime (internet scams) complaints of 2.76 Million and total global financial losses of $18.7 Billion. Although there was a growth in cybercrime complaints and financial losses yearly, the contrasts in the growth between 2017 and 2021 are disturbing. Consequently, there is an urgent need for the Nigerian Government and foreign countries or donor agencies to attack the root cause of Nigerian youths' involvement in cybercrimes to facilitate the eradication of internet fraud. From the report, in 2017 there were 301, 580 complaints with $1.4Billion in losses, which drastically rose in 2021 to 847,376 complaints, and $6.9 Billion in losses (FBI, Internet Crime Report, 2021). The implication is that as long as the unemployment rate increases in Nigeria with the possibility of more graduates from the tertiary institutions, there might arguably be no end to internet fraud perpetration against foreign victims by Nigerian youths unless proactive efforts suggested in this paper are implemented urgently. The preceding may have resulted in Nigeria being tagged as a safe haven for cybercrime perpetration and cyber criminality (Eboibi, 2020; Richards & Eboibi, 2021). However, the next section critically examines the several efforts the Nigerian Government have put in place to eradicate cybercrime in Nigeria and how the efforts are symptomatic rather than attacking the root cause of cybercrimes.

Failure of Current Efforts to Address the Problem

Amid the proliferating nature of Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud, the Nigerian Government made several attempts to eradicate the menace of cybercrimes generally. The Nigerian Government enacted the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 to regulate the activities of internet users. The cybercrime regulation came into force on 15 May 2015, and it is the first Nigerian comprehensive law on cybercrime and computer-related activities. Despite implementing the regulation or cybercrime legal frameworks, there seems to be no reduction in the involvement of Nigerian youths in internet fraud. The irresistible conclusion is that the Nigerian cybercrime regulation alone is not capable of curtailing the menace of cybercrimes, especially with Nigerian political and public officials' continuous utilization of public funds for their personal aggrandisement to the detriment of job creation and infrastructural development. Moreover, it shows that the attempt at enacting a cybercrime regulation and its consequent implementation without dealing with the pervading issues of corruption and unemployment only portrays a symptomatic measure of discouraging Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud. Apart from the legal challenges arising from some of the provisions of the cybercrime legal framework and its implementation, several factors seem to have degenerated from the failure of the Nigerian Government to address the root cause of cybercrime proliferation in Nigeria.

Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 and Punishment

One of the objectives of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015, according to section 1 of the Act and the recent Court of Appeal decision in the case of Raymond Akolo Julius v. Federal Republic of Nigeria (2021) is for the prosecution and punishment of perpetrators of cybercrimes, including internet fraudsters (LPELR-54201 (CA)). Punishment ought to serve as a deterrent to Nigerian youths' involvement in cybercrimes. However, the way and manner some of the provisions of the Act are drafted arguably make it worrisome and challenging to actualise the said objective. Part III of the Act provides for cybercrime offences and penalties. Sections 6,7,14 (2), and 22 are arguably mostly being deployed by cybercrime prosecutors for the arraignment and prosecution of Nigerian youths involved in internet fraud and their co-conspirators. Section 7(1) of the Act mandates owners of cybercafe to register the same with the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) as a business name and subsequently with the Computer Professionals’ Registration Council (CPRC) as a business concern. The drafters of the Act envisage that cybercriminals visit and collude with operators of cybercafe to perpetrate electronic or online fraud through the cybercafe without being punished. Section 7(2) of the Act provides penalty of 3 years imprisonment or N 1,000,000 fine or both against cybercriminals found guilty of online or electronic fraud and N 2,000,000 or 3 years imprisonment or both if the Prosecutor can prove that the owner of the cybercafe connived with the cybercriminal to perpetrate the online fraud. However, it failed to provide any penalty where the cybercafe owner fails to register the cybercafe with the CAC and CPRC. This is a costly oversight by the drafters of the Act.

This makes it difficult for cybercrime investigators to determine which cybercafe has been registered and the inability to get access to the mandatory register for investigation purposes. Moreover, it provides an avenue for cybercafe operators to refuse registration with CAC and CPRC since there is no attached punishment and emboldens them to act contrary to the Act. In the absence of the maintenance of a register, perpetrators of internet fraud would continue to have a field day as it may pose difficulties in getting their details to detect and possibly locate and apprehend them if there is evidence of their involvement in online fraud through the cybercafe. The corollary is that the deterrent effect of section 7 of the Act against Nigerian youths involved in internet fraud is watered down by the absence of a penalty for non-registration of cybercafés.

Moreover, unlawful access to computers, otherwise known as hacking, is arguably one of the techniques deployed by cybercriminals to have access to Personal Identification Information (PII) of victims of internet fraud that they use to defraud them. Interestingly, section 6 of the Act proscribes unlawful access to computers. However, when section 6(1) and (2) of the Act is critically examined, it shows that the basic offence of hacking is not criminalized under the Act. The punishment for perpetrators of unlawful access to computers is limited to those who intentionally access a computer for a fraudulent purpose and obtain data that is vital to national security, computer data, program and commercial secrets without authorisation. The implication is that if a cybercriminal accesses a computer without any of the aforementioned purposes he cannot be held liable for unlawful access to computers under the Act (Omotubora, 2016; Eboibi & Mac-Barango, 2020).

Considering the general difficulties of detecting perpetrators of unlawful access to computers, their intent, and the proliferating nature of Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud, section 6 of the Act does no favor in deterring cybercriminals and others from engaging in internet fraud. Especially when cybercriminals engage in hacking without necessarily doing so for a fraudulent purpose or to obtain data or program. It could be for purposes not specifically mentioned under section 6 of the Act, in which case, again, persons under this category cannot be prosecuted and punished under section 6 of the Act. Comparatively, the UK Computer Misuse Act (CMA) offers a better interpretation of the hacking offence. Section 1 and 2 of the UK CMA favours a “basic hacking offence” (Omotubora, 2016). All that is required under the provision is for the hacker to access a computer without authorisation. It is inconsequential if the hacker is innocent or if the intention is for a malicious or fraudulent purpose. The implication is that once a cybercriminal logs into a computer or attempts to do so, an offence of unlawful access to a computer is committed irrespective of his or her fraudulent intention or for any other purpose (Omotubora, 2016).

The unauthorized access must not be explicitly directed to a data, a program for the cybercriminal to be held responsible for hacking, unlike section 6(1) and (2) of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act. The UK CMA is preferable because it serves to deter all perpetrators of unlawful access to computers irrespective of their intentions and abhors offences that are secondary. A country like Nigeria that is desirous of curtailing the involvement of Nigerian youths in cyber criminality should adapt the basic hacking offence of the UK. So that perpetrators of internet fraud who engage in hacking to retrieve PII of victims can be prosecuted and punished even if they did not do so for the purposes enumerated in section 6(1) and (2) of the Act. This will serve as a deterrent to others and promote the objective of the Act (Omotubora, 2016).

In a related development section 14 of the Act provides for computer-related fraud. Specifically, section 14(2) of the Act proscribes situations where cybercriminals send falsely misrepresented online messages or facts with the intention to commit fraud whose reliance by the recipient or any other person results in any damage or loss. Considering the development of information and communication technology, there is a technical argument and ambiguity about whether the section can be used to prosecute perpetrators where a non-human being receives the misrepresented facts or message. Especially as non-human beings “machines and other devices” cannot be “deceived or misled.” (Omotubora, 2019) However, Adekemi Omotubora (2019) notes that “…section 14(2) does little to address technical arguments and equally technical results that may arise in computer-related deception cases…the law would be inefficient to prosecute identity fraud online or any form of computer fraud because of its patent ambiguity. To eliminate the ambiguity, the Cybercrime Act should be amended to expressly provide (like the UK Fraud Act) that misrepresentations can be made not only to persons but also to machines and other devices.” The implication is that where misrepresentations are made to “machines or other devices” by Nigerian youths involved in internet fraud, there is the likelihood that they will escape punishment under section 14(2) of the Act, which further questions the deterrent effect of the Act against internet fraudsters (Omotubora, 2019). Also, section 22 of the Act provides for identity theft and impersonation. Specifically, section 22(1) of the Act appears to proscribe identity theft, while in reality, the provision seems not to have criminalised acts relating to identity theft. It provides, thus: “A person who is engaged in the services of any financial institution and as a result of his special knowledge, commits identity theft of its employer, staff, service providers and consultants with the intent to defraud commits an offence…” Generally, identity theft occurs when a cybercriminal obtains the PII of a victim (date of birth, name, biometric verification number, credit card number etc) knowingly or without legal permission (Omotubora, 2019).

However, for section 22(1) of the Act, section 58 refers to identity theft as “the stealing of somebody else personal information to obtain goods and services through electronic based transactions.” This implies that section 22(1) fails to proscribe identity theft but instead, the consequence of the fraudulent use of the victim’s PII. Adekemi Omotubora (2016) notes concerning section 22(1): “with respect to identity theft, the law fails to expressly criminalise acts which actually amount to theft but rather focus on results and consequences such as the subsequent use of fraudulently or dishonestly obtained personal information.” Again, section 22(1) of the Act limits persons who can be punished in violation of the subsection to employees of financial institutions. This is inexplicable as it exonerates Nigerian youths involved in internet fraud who are mostly unemployed. It further requires that the employee perpetrator must have acquired the special knowledge sought to be used to commit identity theft and fraud from the financial institution. The subsection again limits special knowledge to services acquired as a financial institution employee. Most Nigerian internet fraudsters would escape punishment because the technical professionalism in engaging in cybercrimes is not derived from services rendered in financial institutions. Therefore, the subsection also limits the commission of identity theft on the financial institution, “staff, service providers and consultants.” It surprisingly excludes other victims of identity theft or fraud. In essence, cybercriminals are allowed to perpetrate identity theft on victims not mentioned in the subsection. As Adekemi Omotubora (2019) further notes, “the only explanation here is that the provision represents an attempt to criminalise insider fraud which has been growing in financial institutions as a result of the adoption of electronic payment systems.” The above loopholes arguably explain why it is difficult to secure convictions under the provisions mentioned above, which is a setback for the objective of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015.

Family Ties, Parents and Cybercrime Academies

Generally, families are significant in determining a child’s behavioural attributes. Economic conditions and other environmental factors of the family contribute to bringing up children with crime-free behavioural attributes, otherwise known as good parenting. Society’s view of a family name and its integrity influences parents to pass positive social values and morals to their children (Ibrahim, 2016). As Suleman Ibrahim (2016) notes, “The sociocultural fear about endangering one’s family name acts as a crime deterrence mechanism.” However, the harsh economic conditions in the Nigerian state accentuated by long-standing corrupt activities by political and public officials and the lack of employment and infrastructural development have made some Nigerian parents to be directly or indirectly involved in cybercrimes, especially internet fraud. Stricken poverty and low living standards have become unbearable that integrity and high or strong moral standards in families have been relegated to the background. Indirectly, parents no longer monitor and supervise their children in accordance with the strong moral standard that the families are known for. Empirical evidence of the preceding is found in studies which interviewed several respondents and victims (Adejoh et al., 2016; Tade, 2013; Ngozi Idemili-Aronu, 2021). Specifically, the authors averred that parents are negligent in questioning the source of wealth of their children even when they are aware it is from an illegal source. Proceeds of internet fraud have made their children (internet fraudsters) breadwinners, taken over parents' responsibilities of siblings' school fees payment, the general welfare of the family, erection of gigantic structures for the parents, and they are made chiefs in the community and in return contribute to the community development. Parents keep mute and refuse to report to law enforcement agents despite the exorbitant and extravagant show of wealth or proceeds of internet fraud because of the benefits (Adejoh et al., 2016; Tade, 2013). Parents who saw their children through tertiary institutions, upon graduation, demand that they must be taken care of by their children despite being unemployed, requesting them to do what other neighbouring youths did that made them so wealthy (Ibrahim, 2016).

Directly, parents now belong to a group of cybercrime syndicates together with their children to perpetrate internet fraud. Parents specifically open bank accounts to receive proceeds of internet fraud. Expensive cars being driven by some internet fraudsters are bought in their parents' name, including gigantic houses with the knowledge that the monies involved are proceeds of internet fraud. Siblings of families now aid each other with arguably their parents' knowledge to scam victims of internet fraud (EFCC, 2021a; EFCC, 2021b; EFCC, 2021c; EFCC, 2021d; EFCC, 2021e; EFCC, 2021f; & EFCC, 2022).

Moreover, children who look up to their parents as role models are now being asked by the same parents to undergo internet fraud training or apprenticeship in cybercrime training or academic centres to learn the art of how to defraud foreign victims. Parents purchase computers, phones and internet connectivity facilities to enhance the successful training of their wards. Parents of internet fraudsters have also organised themselves to protect and legitimise the activities of their children by forming pressure groups such as “Association of Mothers of yahoo boys.” They flaunt the proceeds of internet fraud and dress in the same attires in public or at ceremonies. As Samuel Adejoh et al. (2016) note, “there are indeed cases where parents employ teachers to teach their wards how to become an Internet fraudster”.

The EFCC has recently publicly condemned these acts when it stated thus: “Even more worrisome is the support and collaboration some parents provide for their wards and children who are involved in this despicable trade by procuring for them instruments of fraud such as mobile phones, iPads, and laptops. Some parents go as far as sending their teenage children for apprenticeship, to learn the art of trickery in cyberspace. Recently, a heartbreaking video of an association of yahoo boys’ mothers, wearing asoebi attending an event in a grandiose fashion emerged on the internet, an epitaph of how far we have sunk in values and morals” (Monsurat, 2020; Oseghale, 2022).

Based on the preceding, family ties and parents' involvement in internet fraud presents an even more complex and troubling cybercrime problem. Considering the high number of arrests and convictions of Nigerian internet fraudsters, it would have been beneficial in the fight against internet fraud for cybercrime investigators to extend more of their tentacles to proprietors of cybercrime centres and parents of internet fraudsters. The few activities in this area do not make a profound statement about the quest to curtail the actions of these internet fraudsters. There should be a severe hunt for owners of cybercrime academies throughout the federation. Unless this is done timeously, these academies will continue to spread physically and online, and Nigerian youths will become sophisticated professionals in internet fraud trickery. This will further increase the involvement of Nigerian youths in internet fraud, especially as those trained would also become trainers, thereby passing the knowledge from one generation to the other.

For instance, on 29 January 2021, the EFCC officials arrested ten suspects who were between the age brackets of 20 to 30 years and alleged to be involved in internet fraud at a cybercrime academy in Abuja where they were undergoing internet fraud training. Investigations revealed that the owner of the academy could not be apprehended. However, the academy owner specialises in the training of young Nigerians who desire to be internet fraudsters and, based on their agreement, gets a percentage of whatever proceeds of internet fraud amassed by the trainees. Moreover, he helps some of his trainees to launder the proceeds of the crime (EFCC, 2021g). The point is that the academy owner who is on the run may arguably relocate to other parts of Nigeria to establish another academy there. This will increase the cybercrime problem. Similarly, on 28 November 2019, the EFCC stumbled on another cybercrime academy at Essien Street, Ikot Ibiok Village, Eket Local Government Area, and Akwa Ibom State. Twenty-three trainees were arrested within the age bracket of 19 and 35, excluding the owner of the academy (Sahara Reporters, 2019).

Attacking the Roots Rather than the Symptoms

The previous sections of this paper have shown Nigerian youths increasing involvement in internet fraud, the efforts of the Nigerian Government to curtail the menace and the challenges that have worked against the Government's efforts. This section examines what the Nigerian Government and its institutions must put in place with the international community's assistance to rescue the Nigerian youths and the impacts of their resort to internet fraud.

Direct Resources to Job Creation

Although the regulation of cybercrimes is a positive attempt by the Nigerian Government to curtail internet fraud, it has not yielded the expected results. This is arguably borne out of the fact that the root cause of Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud is yet to receive the adequate attention it requires. Unemployment has been identified as one of the significant problems motivating Nigerian youths' increasing involvement in internet fraud. The rate of Nigerian youth unemployment stood at 53.40 per cent as of December 2020 and it has been projected to reach 53 per cent at the end of 2022 (Trending Economics, 2022). What can be discerned here is that as there is a percentage increase in unemployed youths, so too their increasing involvement in internet fraud. As Tade (2013) rightly notes, “youth involved in cybercrime may also view their actions as a protest against social arrangements in the society. This may serve to neutralize their actions by citing government failure to provide jobs for university graduates and corruption as grounds for engaging in cybercrime.” Consequently, for the Nigerian cybercrime legal frameworks to be effective in their implementation, the Nigerian Government, with the assistance of foreign governments, must devise measures to provide job opportunities for the benefit of Nigerian youths. Unless this is done as soon as possible, Nigerian youths will continue to seek migration to foreign countries through any means in search of greener pastures, which would involve internet fraudsters. This will further exacerbate the global cybercrime problem (Mills, 2020). Nigeria has benefited from financial aid from western countries to sort out her economic woes and underdevelopment. However, these monies have not been appropriately managed due to endemic corruption, poor governance, poverty and dysfunctional institutions (Mills, 2020). As Amenawo Ikpa Offiong et al. (2020) note “as a result of the corruption index, there was a significant negative effect of foreign aid on the growth rate of Nigeria economy in the long-run…” Consequently, for the foreign developmental aid to be effectively utilized in Nigeria, donor foreign agencies and Government must ascertain areas of job creation and directly deploy such funds to construct industries and amenities. Giving aid to the Nigerian Government should be discouraged, and put integrity modalities in place to employ Nigerian youths that meet the basic requirements. Previous experiences have shown that public and political officials would divert such funds for their personal use and arguably empower their unqualified relatives, friends and children with the job opportunity. Moreover, entrepreneurial empowerment and moral education through training and retraining of Nigerian youths with high wages similar to developed countries can keep them from the streets and zero thoughts of internet fraud (Mills, 2020). The deployment of financial aid into mechanized farming based on the experiences of developed nations will facilitate job creation which will also provide a means of revenue for the Nigerian Government (Mills, 2020).

</

Focus Cybercrime Investigations and Prosecutions on Super Internet Fraudsters

Super internet fraudsters spearhead internet fraud syndicates; they are the bosses and the major stakeholders such as those in politics, the force, parents and owners of cybercrime academies. These are the big fishes in the internet fraud industry. Focusing on the low-level internet fraudsters, apprentices, followers and underdogs, as shown in some of the investigations and convictions by cybercrime investigators, does not solve the cybercrime problem. The previous section has shown the significant involvement of parents and owners of cybercrime academies with very few instances of arrests and convictions. With the increasing involvement of Nigerian youths in internet fraud, every parent of an internet fraudster should be adequately investigated to determine their involvement and possibly made to face the wrath of the law. Parents are being used as instruments by internet fraudsters to succeed against foreign victims, including their siblings.

There must be a concerted manhunt for Nigerian parents and siblings of internet fraudsters involved in aiding internet fraud perpetration. The role of owners of cybercrime academies cannot be overemphasised. Passing internet fraud knowledge to the Nigerian youths is the height of cybercriminality, which must not be allowed to continue in Nigeria. Cybercrime investigators must up their game and strategies to comb the nook and crannies of Nigeria in the hunt for these sets of persons. Recent convictions of Nigerian internet fraudsters in the US support the fact that Nigerian cybercrime investigators do not go after super internet fraudsters compared to their US counterparts. In the United States of America v. Abidemi Rufai, aka Sandy Tang (2021), the defendant is a Nigerian youth. Until his arrest for his involvement in internet fraud (wire fraud and aggravated identity theft) involving over $350,000 unemployment benefits in the US, he was a top serving aid on special duties to the Governor of Ogun State, Dapo Abiodun and his close associate and lived in Lekki area of Lagos that the EFCC declared the hub of cybercrimes in Nigeria (Case 3:21-cr-05186-BHS; Department of Justice, 2021b; Department of Justice, 2021c; Edokwe, 2021; EFCC, 2022b). If the US cybercrime investigators did not come for him, no one would have known that he was an internet fraudster, especially since the Nigerian cybercrime investigators turned a blind eye to him. He has consequently entered a plea bargain agreement with the Prosecutors in the matter to plead guilty and a sentence of not more than 71 months in return. There are arguably several of his kinds in Nigerian politics as bosses to other internet fraudsters that are trainees or loyal to them who are having a field day and consequently contributing to the increase of Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud. Most of these young men would be looking up to him, believing that one day they would also be in the corridor of political power and governance just like him. Similarly, in the “United States of America v Ramon Olorunwa Abbas, aka ‘Ray Hushpuppi,’ aka ‘Hush,’ aka ‘Malik,’ & 5 others (2021),” the 1st defendant pleaded guilty to internet fraud that resulted in over $24 million in losses. Again, the US came to the rescue of Nigeria for its inability to investigate and prosecute super internet fraudsters like Ray Hushpuppi despite his public show of wealth in Nigeria and abroad. This case also revealed another super internet fraudster, Abba Kyari, a super cop in the Nigeria Police Force. The court documents alleged that he conspired with Ray Hushpuppi in the internet fraud scheme. The US court has since requested his extradition (United States District Court for the Central District of California; Department of Justice, 2021e)

Amendment of Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 and Rethink of Cyber Prosecutorial Strategy

This paper has alluded to several loopholes in the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 that negatively affects the effective implementation of the regulation and consequently works against the objective of the Act. Section 7(1) of the Act should be amended to reflect a penalty against owners of cybercafes that fail to register their cybercafe as a business name with CAC and business concern with the CPRC. The absence of a penalty does not augur well for the fight against internet fraud in Nigeria. This only exacerbates the problem of Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud. The amendment will facilitate the keeping of details of internet fraudsters who carry out their trade through the cybercafe for investigation and prosecution purposes. Also, concerning the absence of criminalization of the basic hacking offence under section 6 of the Act, it should be amended to be equal per with the UK CMA to ensure that cybercriminals who engage in mere hacking of computer systems without more can face the wrath of the law (Omotubora, 2016). Similarly, the limitation of section 6(1) and (2) of the Act to fraudulent purposes, computer and program etc. should be amended to remove the limitation. Again, this can be done by subjecting the intention to access a computer system to the commission of a felony, misdemeanor or the commission of any crime stated in the Act or any other law (Omotubora, 2016). With this improvement, even if a cybercriminal hacks into a computer system without any of the purposes mentioned in section 6(1) and (2) of the Act, the hacker would be successfully prosecuted. By implication, every act of unlawful access to a computer system will not go unpunished. Section 14(2) raises technical and ambiguous problems concerning misrepresentation made to machines and other devices as earlier stated in this paper. It is consequently suggested that the subsection be amended to include machines and other devices as recipients of misrepresented facts or messages in similar circumstances as the UK Fraud Act (Omotubora, 2019). Furthermore, section 22(1) of the Act attempts to criminalise identity theft. Unfortunately, the contents of the subsection show that the theft of a person's identity seems not to have been criminalised. Hence a cybercriminal cannot be prosecuted or punished for theft of PII. It is hereby recommended for the express inclusion of the theft offence under the Act (Omotubora, 2019). Also, limiting section 22(1) of the Act to employees of financial institutions as perpetrators of the subsection and financial institutions, staff, consultants etc as victims should be revisited by amending the subsection to reflect any person in both circumstances.

Conclusion

The Nigerian cybercrime regulation and other efforts seem not to have had a positive impact in the quest to curtail Nigerian youths' increasing involvement in internet fraud. This has further heightened global financial devastation, and emotional and psychological trauma on foreign victims. The paper reveals that the effort of the Nigerian Government to curtail the cybercrime problem is symptomatic rather than attacking the root cause of the problem. The unemployment of Nigerian youths accentuated by corrupt Nigerian public and political officials is one of the significant reasons Nigerian youths resort to internet fraud. The increasing yearly rate of Nigerian youth unemployment shows the Government’s ineptitude toward the cybercrime problem. Although the Government enacted the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015, some of the provisions meant to prosecute internet fraudsters were inelegantly drafted. Hence, it creates loopholes for internet fraudsters to capitalise on to escaping punishment. Moreover, the unemployment rate of Nigerian youths, coupled with poverty and the low standard of living, have made families and parents to be part of internet fraud syndicates, aiding their children to undergo internet fraud training in cybercrime academies to learn the art of cyber trickery against foreign victims. Consequently, this paper advocates for resources to be directed towards job creation with the international community's assistance and foreign donor agencies. It insists on foreign donor agencies to directly build industries instead of giving the Nigerian Government resources due to corruption experiences. Amendment of provisions of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 identified to have loopholes and the deletion of the plea bargain provision (section 270 ACJA) to facilitate the award of stiffer and severe punishments against internet fraudsters compared to what is obtainable in the US. Life imprisonment penalty is suggested to put away convicted internet fraudsters out of circulation. Again, there is the need for Nigerian cybercrime investigators to focus their investigations and prosecutions on super internet fraudsters instead of low-level ones, apprentices, followers and underdogs. Manhunt for internet fraudster parents, siblings, owners of cybercrime academies and bosses of these young boys must be explored if Nigeria must have any impact in the fight against internet fraud.

References

Adejoh, S.O., Alabi, A.A., Adisa, W.B., & Emezie, N.M. (2019). Yahoo boy’s phenomenon in Lagos metropolis: A qualitative investigation. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 13(1), 2-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Aiezza, M.C. (2020).Chapter four-Too good to be true. A discourse analysis of the Australian online scam prevention website.In G. Tessuto, (Eds.), The Content and Media of Legal Discourse.

Akanle, O., & Shadare, B.R. (2020). Why has it been so difficult to counteract cybercrime in Nigeria? Evidence from an Ethnographic study. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 14(1), 29-43.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Brody, R.G., Kern, S., & Ogunade, K. (2020). An insider's look at the rise of Nigerian 419 scams. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(1), 202-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Chude-Sokei, L. (2011). Invisible missive magnetic juju: On African cybercrime. West Africa Review, 18(1), 1-9.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2015a). 23 September: Federal grand jury indicts Nigerian man for role in “business email compromise” scheme that caused attempted $1.3 million loss to U.S. companies.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2015b). 24 September: Federal grand jury indicts Nigerian man for role in “business email compromise” scheme that caused attempted $1.3 million loss to U.S. companies.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2017). 28 August: Nigerian man sentenced for role in “business email compromise” scheme that caused $3.7 million loss to U.S. companies.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2021a). 11 March: Nigerian national sentenced to nine years in federal prison for a money laundering conspiracy related to a romance scam and other fraud schemes.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2021b). 17 May: Nigerian citizen charged with defrauding Washington state employment security department of over $350,000.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2021c). 26 May: Nigerian national indicted for conspiracy, wire fraud and aggravated identity theft for fraud on Employment Security benefits.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2021d). 24 June: Nigerian national indicted in Washington state for fraud on COVID-19 economic relief programs.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2021e). 28 July: U.S. attorney’s office, central district of California, six indicted in international scheme to defraud Qatari school founder and then launders over $1 million in Illicit.

Department of Justice (DOJ). (2021f). 20 October: Eight Nigerians charged with conspiring to engage in internet scams and money laundering from Cape Town, South Africa.

Eboibi, F.E. (2018). Handbook on Nigerian Cybercrime Law. Justice Jeco Printing & Publishing Global.

Eboibi, F.E. (2020). Concerns of cyber criminality in South Africa, Ghana, Ethiopia and Nigeria: Rethinking cybercrime policy implementation and institutional accountability. Commonwealth Law Bulletin, 46(1), 78-109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Eboibi, F.E. (2022). Law and human perspectives to cybercrime perpetration in Africa: Nigeria and Ghana in particular: Part 1. Computer and Telecommunications Law Review, 28(1), 15-21.

Eboibi, F.E., & Mac-Barango, I. (2020). Chapter 5- The Hacker and Nigerian Cybercrime Prosecutor: Tips for Successful Prosecution. In Cybercrime: New Threats, New Responses, Proceedings of the XVth International Conference on Internet, Law & Politics. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, 85-103.

Eboibi, F.E., & Ogorugba, O.M. (2022). Rethinking cybercrime governance and internet fraud eradication in Nigeria.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021a). EFCC Arrests son, mother for alleged N50m internet fraud.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021b). EFCC arrests son, mother, others for internet fraud in kaduna.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021c). Son, father in EFCC’s net for alleged internet.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021d). Son, mother three others convicted of internet fraud in kaduna.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021e). Court convicts son, mother, girlfriend for $902,935 Internet fraud in asaba.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021f). EFCC arrests siblings for alleged internet fraud in lagos.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021g). EFCC Arrests 10 Yahoo-Yahoo ‘Students’ In Abuja.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2021h). Official website-news, arrests and convictions.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2022). Yahoo boy's mother jailed five years in Benin.

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). (2022b). Lekki Now Hotbed of Cyber Crime – EFCC 402 suspects arrested in three months.

Edokwe, B. (2021). FBI nabs Dapo Abiodun’s moneybag Bidemi Rufai over N312 billion job syndicate fraud.

FBI, Scams and safety: Common fraud schemes.

Gillespie, A.A., & Magor, S. (2019). Tackling online fraud. ERA Forum, 20(3), 439-454.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Hassan, A., Lass, F.D., & Makinde, J. (2012). Cybercrime in Nigeria: Causes, effects and the way out. ARPN Journal of Science and Technology, 2(7), 626-631.

Ibrahim, S. (2016). Causes of socioeconomic cybercrime in Nigeria. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Cybercrime and Computer Forensic (ICCCF), 1-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Idemili-Aronu, N. (2021). Get rich syndrome: Examining the fight against cybercrime in Enugu State, Nigeria. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 10, 1390-1396.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Internet Crime Report. (2021). Federal Bureau of Investigation 2021. Internet crime complaint center.

Mills, G. (2020). The African security intersection: Pathways to partnership.

Monsurat, I. (2020). African insurance (Spiritualism) and the success rate of cybercriminals in Nigeria: A case study of yahoo boys in Illorin, Nigeria. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 14(1), 300-315.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Offiong, A.I., Etim, G.S., Enuoh, R.O., Nkamare, S.E., & Bassey, G. (2020). Foreign aid, corruption, economic growth rate and development index in Nigeria: The ARDL approach. Journal of Research in World Economy, 11(5), 348.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Omotubora, A. (2019). Old wine in new bottles? critical and comparative perspectives on identity crimes under the Nigerian cybercrime Act 2015. African Journal of International and Comparative Law, 27(4), 609-628.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Omotubora, A.O. (2016). Comparative perspectives on cybercrime legislation in Nigeria and the UK-a case for revisiting the hacking offences under the Nigerian cybercrime Act 2015. European Journal of Law and Technology, 7(3), 2-3.

Oseghale, W. (2022). EFCC: Separating facts from fiction.

Richards, N.U., & Eboibi, F.E. (2021). African governments and the influence of corruption on the proliferation of cybercrime in Africa: Wherein lays the rule of law? International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 35(2), 131-161.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Sahara Reporters. (2019). EFCC Arrests 23 men from Yahoo-yahoo school.

Tade, O. (2013). A spiritual dimension to cybercrime in Nigeria: The yahoo plus phenomenon. Human Affairs, 23(4), 689-705.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Trending Economics. (2022). Nigeria Youth Unemployment Rate, 2022 Data-2023 Forecast-2014-2021 Historical.

U.S. Attorney’s Office. (2020). Nigerian businessman pleads guilty to $11 million fraud scheme.

U.S. Attorney’s Office. (2021a). Nigerian national sentenced to prison for $11 million global fraud scheme.

U.S. Attorney’s Office. (2021b). Six indicted in international scheme to defraud Qatari school founder and then launder over $1 million in illicit proceeds.

United States Attorney Office. (2017). Nationwide identity theft and IRS tax fraud scheme results in federal prison sentence.

Utomi, J.M. (2022). Unemployment and a nation’s 40 per cent of hopelessness.

Whitty, M.T. (2018). 419-it's just a Game: Pathways to cyber-fraud criminality emanating from West Africa. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 12(1), 97-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Received: 13-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-12325; Editor assigned: 16-Jul-2022, PreQC No. JLERI-22-12325(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Jul-2022, QC No. JLERI-22-12325; Revised: 28-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-12325(R); Published: 05-Dec-2022