Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 3S

Deconstruction Orientation of Village Forest Utilization Policy

I Wayan Rideng, Faculty of Law Universitas Warmadewa Denpasar

I Nyoman Putu Budiartha, Faculty of Law Universitas Warmadewa Denpasar

Ketut Adi Wirawan, Faculty of Law Universitas Warmadewa Denpasar

Citation Information: Rideng, I.W., Budiartha, I.N.P., & Wirawan, K.A. (2021). Deconstruction orientation of village forest utilization policy. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 24(7), 1-9

Abstract

Forests as the national development capital have real benefits for the life of the Indonesian people, in the form of; ecological, socio-cultural and economic. For this reason, forests must be managed, protected and used sustainably for the welfare of the community. Efforts to conserve forests cannot be carried out by the state without the participation of local communities in forest areas, considering that local communities will face various actions against the forest. To increase the role of the community in the forestry sector, therefore the issuance of the Minister of Environment and Forestry Regulation No. P.83/Menlhk/Setjen/Kum.1/10/2016 concerning Social Forestry, the arrangements include: village forest, community forest, community plantation forest, forestry partnership; and customary forests. Regarding the study location at Wanagiri Village, the Governor of Bali issued a Decree on Village Forest Management Rights. Juridically, the policy on the role of indigenous peoples has not been determined. The implication for the technical arrangement is that there is an attitude of ambiguity, even though the synergistic role between the Customary Village and the Official Village as Village Forest Management Rights recipients is very good at improving community welfare and maintaining the value of local wisdom. This research focuses on Social Forestry, namely Village Forest which is analyzed from the issuance permit of the Wanagiri Village Forest, with the concept of Village Forest and its implementation, that the Village Forest program runs without involving customary society even though village institutions obtain the management rights of Village Forest requires the participation of customary institutions, both in form of human resources, consideration of action, and capital. So that the research is aimed at deconstructing the orientation of the Village Forest Program, so that it can work in synergy with customary institutions.

Keywords

Deconstruction, Policy Orientation of Village Forest, Wanagiri Village.

Introduction

Forests are one of the natural resources that are fully controlled by the state in realizing ideals from state science perspective (Article 33 section 3 of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia). It cannot be denied that the existence of forests experiences dynamics from the level of policy to the practice. As an illustration, in fact that from 2019 to September the data showed that forest and land fires in Indonesia, reached 857,756 hectares. It consists of 630,451 hectares of mineral land and 227,304 hectares on peat. This figure is an increase of 160% compared to the area in August 2018, around 328,724 hectares. Indeed, the degradation of forest conditions is also triggered by non-natural (human) events such as illegal logging and others (Lubis, 2007).

In fact, it is stipulated that the area of forest area that must be maintained by the government and regional government on each island is at least 30% (thirty percent) of the area of the watershed and / or island with a proportional distribution. (The author's language refers to Article 18 of Act No. 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry) Authentically it can be interpreted that the minimum area should not be used as an excuse to convert existing forests, but rather as a warning of the importance of forests for the quality of life of the community. On the other hand, provinces and regencies/municipalities with forest area of less than 30% (thirty percent) need to increase the forest area. (Explanation of Act No. 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry) (Law, 1999). It is realized that the state cannot afford to preserve the existence and nature of forests without the participation of the community as a social community that lives and resides in the area around the forest. Logically, of course those who live in the vicinity of the forest area can play a more effective role in preserving the forest (Norris, 2008).

Furthermore, in 2016 the Minister of Environment and Forestry Regulation Number P.83 / Menlhk / Setjen / Kum.1 / 10/2016 concerning Social Forestry was issued, in which in Article 4 stipulates that the scope of this regulation includes: village forest, forest community, community plantation forests, forestry partnerships; and customary forests (Regulation, 2006). It can be observed that this social forestry program policy applies throughout Indonesia, including in Bali. The forest area of Bali Province which has been confirmed and defined covers an area of 136,831.66 Ha (in 2014) which consists of land and water forest areas with functions as in the following Table 1:

| Table 1 Distribution and Types of Forests in Bali Province in 2014 | |||

| No | The Function of Forest Area | Width (Ha) | Note |

| 1 | Tourism Forest | 4.113,19 | |

| 2 | Nature Reserve Forest | 1.773,80 | |

| 3 | Natioanal Forest | 23.143,86 | |

| 4 | Botanical Garden Forest | 1.129,19 | |

| 5 | Protected Forest | 97.407,95 | |

| 6 | Limited Production Forest | 7.204,09 | |

| 7 | Permanent Production Forest | 1.872,80 | |

| 8 | Convertible Production Forest | 186,78 | |

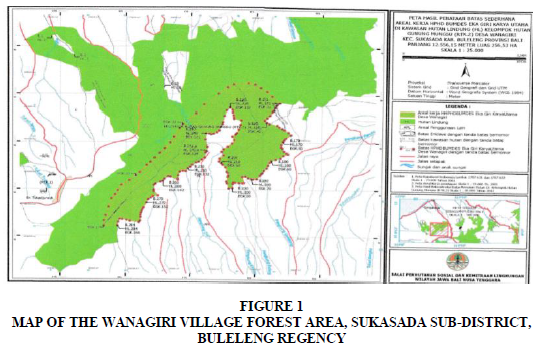

In addition, the forest area of Bali Province has not yet reached the minimum area of 30% of the provincial area (563,286 ha), in accordance with the provisions of Government Regulation Number 44 of 2004 concerning Forest Planning. Based on these conditions, in 2015, the Governor of Bali Province issued a Village Forest Management Right Decree (hereinafter referred to as HPHD) to 17 villages in Bali, one of which is Wanagiri Village. Forest areas that have been granted HPHD permits are protected forest areas, especially forest areas that are experiencing degradation or deforestation (Figure 1) (Nugroho, 2006).

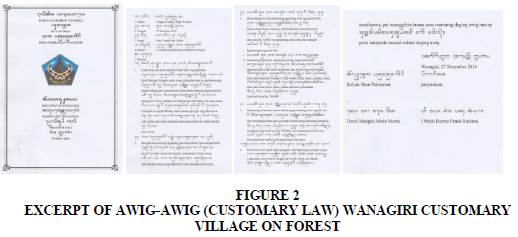

In line with that, the regulation regarding social forest is regulated by the concept of “customary forest” as forest that is within the territory of customary law communities. (Article 1 point 12 Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia Number P.83 / Menlhk / Setjen / Kum.1 / 10/2016 concerning Social Forestry). It can be assumed that the HPHD for the forest in Wanagiri Village was issued because the Wanagiri Forest does not enter the Wanagiri Indigenous Village area so that the permit issued is not customary forest. The implementation of the Wanagiri HPHD then runs for the benefit of tourism, without involving traditional institutions (for example: Village Credit Institutions (LPD)). In fact, the implementation requires a synergy between the official village (the HPHD recipient) and the customary village (the customary community that is close to the forest area). In reality through the researchers' initial observations, data shows that the Wanagiri Indigenous Village has had rules at the customary village level in the form of Awig-Awig (customary law) which contains about forests in the perspective of religious values and local wisdom (Figure 2).

The initial assumption is that if we refer to the issuance of the permit, the orientation of the Village Forest Policy (HPHD) in Wanagiri Village is only rigidly oriented towards the Official Village without any orientation influence on the Wanagiri Indigenous Village. Therefore this research discusses more deeply about the orientation that is aimed at the current Village Forest policy as well as the policy orientation needed by HPHD in the future so that it can be synergized with local wisdom and support forest conservation in a sustainable manner (Soekanto, 1979).

Through an initial description of the background and urgency of this research, the picture of the state of the art or novelty is the social forestry policy in particular; Village Forest has a change in concept or meaning, so that in the Village Forest policy there are also interests and roles of Indigenous Villages. Clear Starting from this background, there are problems that want to be studied in this study, namely:

1. How is the Village Forest Policy Implemented in Wanagiri Village?

2. What is the Ideal Orientation of Village Forest Policy in Wanagiri Village?

Research Methods

This study uses an empirical legal research method (socio-legal research), because it focuses on the study of the mismatch between factual conditions in the field and normative settings, especially in the conceptual order, using the following approaches: statute approach, conceptual approach, and analytical approach and sociological approach. Legal material search techniques use field study techniques, document studies, and analysis of the study uses qualitative analysis.

Result and Discussion

Regulation Implementation of Village Forest policy in Wanagiri Village

Administratively, Wanagiri Village is in the Sukasada District, Buleleng Regency, Bali Province. The topography of Wanagiri Village is steep hills with an altitude of 1,200 meters above sea level and the air tends to be cold. The income of the population is dominant as farmers of cloves, coffee, cocoa and other forest products. Geographically and administratively Wanagiri Village is one of 129 villages in Buleleng Regency, and has an area of 15.75 km2. Topopographically, it is located at an altitude of between 600 and 1,220 meters above sea level (masl). The position of a hilly village which is located in the southern part of Sukasada District, Buleleng Regency is directly adjacent to the west of Gobleg Village, Banjar District, and in the east it is bordered by Pegayaman Village, north of Gitgit Village, Sambangan Village and Ambengan Village, and in the south it is bordered by Pancasari Village. In the past, this area was still a forest with dense trees. Many people feel that this area is said to be haunted. Because tens of years ago, this place was used as a dumping ground for corpses. Besides that, in the Village Forest area, 3 (three) beautiful waterfall attractions have been opened, the water is clear and access is easy to reach, namely the Banyumala Waterfall Tourism Object, Wana Amertha Waterfall and Pucak Manik Waterfall (Sumaryono, 1990).

Regarding the Village Forest Management permit in Wanagiri Village, it can be observed that the philosophy of the right to manage the Village Forest is actually in order to reduce poverty, reduce unemployment, and also minimize the social gap that occurs in the community. Based on the Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia Number: P.83 / MENLHK / SEKJEN / KUM.1 / 10/2006 concerning Social Forestry. Futher examination showed that the issuance of regulations related to the Social Forestry system has the main objective of improving community welfare. Its form is to provide access to communities around the forest to manage or cultivate plants in the forest area by planting long-term, medium-term, fruit and seasonal crops so that people have a better income. Thus, poverty and unemployment that always shackle communities around and inside forest areas can be significantly reduced. In this context, the government provides facilities for the community to access permits in order to be able to manage Village Forests under the Social Forestry scheme.

The right to manage Village Forest in legal terminology is a right granted by the state to village institutions within a certain period of time and in a certain amount of area. Through this right to manage state forests, communities who are members of village communities or customary law are given access by laws and other regulations, to enter activities in forest areas and manage state-owned forests. The social forestry management system must not violate the principle of justice, the principle of sustainability, the principle of legal certainty, the principle of participation, and the principle of accountability.

The Social Forestry area in the Village Forest scheme according to the provisions in Article 6 Section 1a-1c, is only carried out in the function of production forest areas and/or protected forests that have not been burdened with permits, protected forests managed by Perum Perhutani (Java Island only) and certain areas in Forest Management Units. In production forest areas, timber and other forest products can be harvested, but still based on the principle of sustainability. Meanwhile, in protected forest areas, it is not allowed to cut trees for timber harvesting. What is allowed is the use of non-timber forest products and environmental services. In the Conservation Forest of the Social Forestry model that only allows Conservation Partnerships, given the conservation function, the activities allowed are very limited in the form of utilization of environmental services and utilization of a very limited Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs). To distinguish village forest or other schemes from the function of the forest itself is based on the function of the location / area of the forest, and the subject is the local community as the actor who has access to management and a model for the use of the forest area.

The enactment of Act No. 6 of 2014 concerning Villages, since January 15, 2014, has included a variety of dynamics of its own. Even though it has been accompanied by an implementing regulatory device, namely Government Regulation Number 43 of 2014, the implementation of this regulation is still being debated by many parties. The condition that is debated is around two material objects in the provisions of this regulation, namely the New Order Village (or the term official village) and the Indigenous Village. New Order Village is a village formed through Act No. 5 Year 1979 and continued with Act. No. 22 Year 1999. Meanwhile, the official village is an original village which during the Dutch colonial era was known as volksgemeenschappen or indigenous peoples. For this material object, Bali certainly has different characteristics about the meaning of a village with other villages in Indonesia. This characteristic is marked by the remain of strong role of the customary village in addition to the official village which includes more disagreements over this arrangement, such as regarding territorial status and limits of authority based on a socio-historical foundation.

In Bali there are 2 (two) types of villages Indigenous Villages which have now been strengthened through the Bali Provincial Regulation No. 4 of 2019 concerning Indigenous Villages in Bali, which have existed since ancient times. The official village which has also been regulated in a separate Act. The existence of these 2 (two) types of villages is duality, or it is often said to be dualism. This is wrong, because the reality of the two villages is running simultaneously, parallel together, in line andin one direction. There is no dualism, overlapping, crossing each other. This must be understood that it is different from indogenous villages in other areas. Indigenous village in Bali formed about 1000 years ago by Mpu Kuturan. This is what unites the Hindus, which previously consisted of sects, who were fighting and fighting with each other. To unite these sects, a indigenous village is formed which is inhabited by Krama (people of the indigenous) village which has at least 3 (three) temples called Kahyangan Tiga, and one setra (Cemetary). This is the condition. All Krama villages are subject to the rules called Awig-Awig (Customary Law) and Perarem (Decision made by Indigenous People) which are made by the customary village concerned.

The Ideal Regulation of the Village Forest Policy Orientation in Wanagiri Village

Indigenous villages in Bali have values that are identical to local wisdom. As stated in Article 1 point 8 Bali Regional Regulation No. 4 of 2019 concerning Indigenous Villages in Bali:

"Indigenous Village is a customary law community unit in Bali which has territory, position, original composition, traditional rights, their own assets, traditions, social manners from generation to generation in the ties of a holy place (kahyangan three or kahyangan village). Duties and authorities as well as the right to regulate and manage their own household”.

Local wisdom is understood as a local idea, the intelligence of the local community, and the ability that the community has had from a long time ago and has been passed down from generation to generation in order to manage the universe for the benefit of the community. The scope of local wisdom includes:

1. The values of local communities that live and develop without manipulation;

2. Local knowledge;

3. Local human resources; and

4. Local solidarity.

When connected with this research, what is meant by local wisdom is the ideas and intelligence of the people who are the object of this research in order to manage the natural environment. Meanwhile, the characteristics of local wisdom are:

1. Able to last a long time;

2. Able to select the entry of foreign cultures that come from outside;

3. Able to integrate foreign culture with local culture; and

4. Provide a direction of change to make it better than the previous situation.

The local wisdom of the Balinese is based on the philosophy of life of the teachings of Hinduism, namely the Tri Hita Karana which has been adhered to and implemented in their daily life for generations. The concept of Tri Hita Karana cosmology is a philosophy of tough life. This philosophy has a concept that can preserve cultural diversity and the environment in the midst of globalization and homogenization. A Balinese cultural philosophy of Tri Hita Karana which emphasizes on the balance theory states that Hindu communities tend to see themselves and their environment as a system that is controlled by balance values and manifested in the form of behavior. Tri Hita Karana etymologically formed from the words: tri which means three, hita means happiness and karana which means because or what causes, can be interpreted as 3 (three) harmonious relationships that cause happiness. The Balinese indigenous people teach their people and adhere to the concept of Tri Hita Karana (the concept of teachings in Hinduism), and implement it in everyday life. The 3 (three) harmonious relationships are believed to bring happiness in this life, where in Hindu society terminology is manifested in 3 (three) elements, which are referred to as Parahyangan, Pawongan, and Palemahan.

Meanwhile, with regard to the Wanagiri Village Forest Management Rights (HPHD), the Wanagiri Village Forest management will be prioritized to become a tourist destination. In priority, the purpose of traveling both in groups and individually is nothing more than just looking for fun or joy. After conveying the purpose of the people traveling, then being linked to the Wanagiri Village Forest as one of the tourism destinations, the linkage point of the relationship lies in the Wanagiri Village community with the forest environment as a place to live, and the forest environment is used as a place to carry out various kinds of life activities since the community Wanagiri Village started to exist and got to recognize group life. The life of the Wanagiri Village community is very dependent on the forest and its natural environment. Therefore, instinctively, if people have the instinct to return to the forest or nature, it is not really a strange thing. In general, human society instinctively has the character of getting bored with various kinds of environment, especially the complex urban environment with many crucial problems and difficult to solve.

Along with the implementation of the Social Forestry program, especially after the issuance of Ministry of Forestry Regulation No. 49/Menhut-II/2008 concerning Village Forests. Aiming at improving the welfare of the people living around the forest, without forgetting forest sustainability after going through the institutional and administrative preparation process, in 2010 the Ministry of Forestry issued Decree Number 629/Menhut-II/2010 dated 11 November 2010 concerning the Designation of Village Forest Areas for 7 (seven) The village in Buleleng Regency covers an area of 3,041 hectares, including one of which is the Wanagiri Village Forest. After institutional facilitation, finally in 2015 the Governor of Bali Decree Number 2017/03-L/HK/2015 was issued regarding the granting of Village Forest Management Rights in Protected Forest Areas covering an area of 3,041 hectares to 7 (seven) village institutions in Buleleng Regency including BUMDesa (Village-owned enterprises) (Regulation, 2016). Eka Giri Karya Utama to manage Wanagiri Village Forest. There are several forest groups that are members of BUMDesa Village-owned enterprises (presented in the Table 2), as follows:

| Table 2 Forest Groups of Bumdesa Village-Owned Enterprises | ||

| No. | Nama of Group | Members |

| 1 | Wisata Banyumala Group | 40 |

| 2 | Tani Hutan Wana Merta Group | 76 |

| 3 | Air Terjun Pucak Manik Group | 15 |

| 4 | Tani Hutan Pucak Manik Group | 30 |

| 5 | Air Terjun Banyu Wana Amerta Group | 68 |

| 6 | Tani Hutan Jagra Wana Group | 68 |

It can be traced that the management of the Wanagiri Village Forest which is oriented towards the development of sustainable tourism will be identical to the value of local wisdom that exists in the community and that area. This is then interesting as a paradox of meaning, in the concept of a village to develop not only in the official village as an administratively structured institution, but also in customary villages that do exist and grow in such a way around the Wanagiri Village Forest area.

Still in the context of forest management as a national orientation, it cannot be denied that there are interests or rights of indigenous peoples (Krama adat), who uphold the value of local wisdom, as one of the wealth and support for tourism in the Wanagiri Village Forest that deserves attention to their rights and interests. So it is very appropriate that the Wanagiri Village Forest Management Rights Policy (HPHD) also involves the role of Indigenous villages, so that local wisdom becomes a support for tourism to obtain the energy of "intake" in the form of financing or funding as supporting "operational costs" in cultural preservation and local wisdom.

Conclusion

The general condition of the Wanagiri Village Forest remains quite good even though there are several open lands planted with thousand broken flowers but the tree planting process has been carried out and the community is also very enthusiastic about carrying out reforestation and replanting activities. The impact of the Village Forest is greatly felt by the people of Wanagiri Village, especially for village tourism, because with the Village Forest policy there is a lot of potential that can be explored by the community in Village Forests related to tourism and can create new jobs and increase the added value of community income. especially in the tourism sector. Likewise, the community is also increasingly aware of the sustainability of the forest because the tourists who attend really want the nature and sustainable natural conditions.

Based on the factual conditions of the implementation of the Wanagiri Village Forest policy, it can be observed that there is synergy between the Official Village and the Indogenous Village as a paradox in the concept of "village" as in the Village Forest management permit policy made by the government. This is evidenced by the posting of several things about forest management in the “Awig-Awig” (Customary Law) of the Wanagiri Indigenous Village. This needs to be noted separately in the HPHD implementation policy so that it fulfills the value of justice (does not cause discrimination), while maintaining the value of local wisdom as a support for the Wanagiri HPHD policy.

References

- Law. (1999). Act no. 41 year concerning forestry.

- Lubis, S. (2007). Public policy. Mandar Maju, Bandung.

- Norris, C. (2008). Dismantling Jacques derrida's theory of deconstruction. Ar-Ruzz Media, Yoyakarta.

- Nugroho, R.D. (2006). Public policy for developing countries formulation, implementation and evaluation models. Elex Media Komputindo Gramedia, Jakarta.

- Regulation. (2006). Regulation of the minister of environment and forestry of the republic of Indonesia number: P.83 / MENLHK / SEKJEN / KUM.1 / 10/concerning Social Forestry.

- Regulation. (2016).Regulation of the director general of social forestry and environmental partnershipsnumber P.11/Pskl/Set/Psl.0/11/concerning Guidelines for Verification of Village Forest Management Rights Applications (HPHD).

- Soekanto, S. (1979). Law enforcement and legal awareness. Complete Text on a paper at the 4th National Law Seminar, Jakarta.

- Sumaryono, E. (1990). Hermeneutics, a philosophical method. Kanisius, Yogyakarta.