Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Democratic Concept of Legislation for the Establishment of Regional Regulations (Case Study of the Establishment of Qanun Aceh)

M. Yasir Putra Utama, Universitas Syiah Kuala

Faisal, Universitas Syiah Kuala

Husni, Universitas Syiah Kuala

M. Saleh Sjafei, Universitas Syiah Kuala

Rudy Pramono, Pelita Harapan University

Keywords:

Establishment of Local Law, Legislation, Constituents and New Institutions

Abstract

The process of making a Regional Legal Product must go through the standard of legislation mechanism, which is regulated by legislation. In the rule explains the process that must be done step by step. The organ of the legislator of the regional law is a legislative institution whose members are the result of direct elections by the community and after being elected then make them as representatives of the people placed in one institution. Elections in Indonesia use a party system so that every legislative member who is elected in addition to carrying out the task of representing the people also carries the interests of political parties used in the general election. The interests of the constituents and the interests of the party follow each other's interests of each member of the legislature who sits in the House of Representatives and in the discussion of a draft qanun always contains the interests of both sides. The process of establishing regional legal products takes a long time, because the existing system still uses the instructions of the existing legislation and in the rule is not by default the method of formation of qanun by the board is set, but no one has ever change the method, and in this study in trying to come up with a new concept of methods and mechanisms for the formation of better regional laws and will shorten the timing of the legislation process and avoid political party pressure for council members who representing in the board. The establishment of regional law will be carried out by an independent institution and members are personnel who have skills in the formation of qanun intended. This institution will provide maximum product results and with a short time and legal product results will be more appropriate.

Introduction

The term Legislation is a literal translation of the English language legislation. When viewed both grammatically and in the realm of legal science, 'legislation' contains a dichotomous meaning, which can mean (1) the process of forming a law (legislation), and it can also mean (2) legal products (legislation). However, based on searching various references and dictionaries, it turns out that each dictionary is not the same in providing the meaning of this legislation. Some give a double meaning and some give a single meaning. Elizabeth A. Martin and Jonathan Law, for example, define legislation as 1) the whole or any part of a country's written law, 2) the process of making written law (Elizabeth, 2006). Likewise with John M. Echols and Hassan Shadily translating legislation as (1) legislation, (2) making laws (John, 1995). Two figures of legal positivism, namely Jeremy Bentham and John L. Austin associated the term legislation as "any form of law-making" (Jeremy, 1996). The definition of this legal positivism figure is different from that of S.J. Fockema Andreae, which states that legislation, wetgeving or gesetzgebung can mean (1) the process of forming state regulations, and (2) legislation as a result of the formation of regulations, both at the central and regional levels (Maria, 1998).

According to M. Solly Lubis, "... what is meant by Legislation is the process of making state regulations. In other words, the procedure starts from planning (design), discussion, ratification or stipulation and finally the enactment of the relevant regulations "(Solly, 1995). However, normatively, Article 1 number 1 UUP3 defines the definition of the formation of statutory regulations as "... the process of making laws and regulations which basically starts from planning, preparation, preparation techniques, formulation, discussion, ratification, promulgation, and dissemination ”.

Based on this definition, it can be argued that the policy formulation of statutory regulations is only one part of the formation of statutory regulations. In the perspective of legal science, the formation of law (legislation) of a country cannot be separated from the “legal way” of the nation concerned. In Satjipto Rahardjo's constellation, the "method of punishment" of a nation shows that nations have a kind of right to pursue their own way of law or to adopt the Rule of Law. Because it is a right, a nation can freely determine the "method of law. "Alone without coercion from others.

Legislation as part of the method of law in a country must also be approached from the optics of pluralism. The awareness of pluralism in the future will clearly become a world trend. This can be seen, for example, from Werner Menski's words as follows: "It places legal pluralism more confidently into the mainstream study of comparative law, addressing some of the serious deficiences of comparative law and legal theory in a global context"(Werner, 2006). This understanding of legal pluralism cannot be separated from the discussion about the decline in traditional legal science. What is meant by traditional legal science is the science that discusses law solely in the context of the law itself. Meanwhile, the new law science does not stop at just discussing the law alone, but is related to the social habitat where the law is located.

In line with this thought, Brian Z. Tamanaha discussed his big thesis by saying that law is nothing but a reflection of its society as well as functioning as a guardian of society's order - "the idea that law is a mirror of society and the idea that function of law is to maintain a legal order" (Brian, 2006), This framework of thought which in Tamanaha terms is referred to as the mirror thesis.

There are at least three great traditions in the “way of punishment” (John, 1969) of the nations of the world. As stated by John Henry Merryman, in this world there are three main legal traditions, namely: the civil law tradition, the common law tradition, and the socialist law tradition. Quoting Merryman, Peter de Cruz stated the following:

“It has become established practice to classify the legal systems of the world into three main types of legal families or legal traditions: civil law, common law and socialist law. A legal tradition has been defined as a set of 'deeply rooted historically conditioned attitudes about the nature of law, the role of law in the society and the political ideology, the organization and operation of a legal system” (Peter, 1999).

In the history of legal development, the method of law or the ROL of a nation has been started since before Christ. Aristotle and Plato from the Greek period were already struggling with the ROL problem. Plato insisted that the government be bound by law. The Romans also made their own contribution to the ROL tradition. Cicero, a century BC, had the courage to criticize the king that a king who disobeyed the law was a despot. In the period 529 to 534 Emperor Justinian carried out a codification consisting of three books, namely: Codex (compilation of royal legislation), Digest (written work of jurists), and Institute (legal textbooks).

After the collapse of the Roman Empire which meant the collapse of the ROL with all its studies, it reappeared in the 16th century. Roman and German law science became the standard in the realm of legal science that is still felt today. Progress in studying the law by G.C.J.J. he called van den Bergh an advancement from the GeleerdRecht (scholl-rules law). The word geleerd reflected how sophisticated the understanding of law was at that time (Bergh, 1980). ROL in Germany emerged as Rechtsstaat. Seen from a purely scientific perspective, every country is a Rechtsstaat, regardless of whether the country is democratic, totalitarian, fascist, Bolshevist, or an absaolut kingdom. The essence of Rechtsstaat lies in the separation between the political structure of the state from its legal arrangement. Meanwhile, the function of law is to guarantee independence and certainty. The function of such law is none other than the work of the bourgeoisie which later gave birth to liberal law. On a broader level, it can be argued that the law produced in the current Rechtsstaat framework is vertical, one-way (top-down), from state rulers to citizens.

Theoretically, legislation can be made, among others, by: the government, the people, people's representatives, or a combination thereof. In the Netherlands, laws are made by the government together with the people's representatives. The slightly different thing is in Italy and Switzerland where some decisions are taken by the people through referendums, while others by the people's representatives. While in a country ruled by a dictatorship, the law is made by the government (Addis, 2008).

For the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia, the institution that forms the law is the legislative body, both at the center (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat/DPR) and at the region (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah/DPRD). 1945 Constitution as well as UUP3 and Law No. 23 of 2014 explicitly stipulates that the function of legislation (the function of establishing legislation) is in the DPR and DPRD. However, this legislative function is not an independent function of the Indonesian legislature, but the institution must work with the executive both at the center and in the region when carrying out its legislative functions.

In the sociological perspective, the law-making organ is not just seen as a law factory (law factory), "but an arena in which to compete to share the interests and power that exist in society". Based on such optics, the law making organs clearly reflect the configuration of powers and interests that exist in the society.

In a country that adopts a democratic system, the distribution of various interests and powers is through a system of representation and general elections. In the context of such a democratic system, "The inclinations of thought, education, social origins and others of the members of the law-making body will also determine the Laws made". It should be understood that in the formation of modern law it is not just a standard formulation of material with all its juridical standards, but the process begins with making a political decision first.

In the description of Ann Seidman e.al-although the discussion is only specifically about the establishment of legislation, but can be filed for the purpose of the legal legislative process in general-the legislative process should pay attention to 6 (six) things namely: (1) the origin of the draft law (a bill's origins), (2) the concept paper, (3) prioritize, (4) drafting the bill, (5) research, and (6) who has access? (who has acces and supplies input into the drafting process?(Seidman, 2001)

Thus, the legislature should be able to answer the 6 (six) questions as follows: How to formulate the idea of the law that goes into a system-and from whom? Who originally explained the idea - and how? Who decides, with what criteria and procedures, in an effort to use the limited resources available when drafting some legislation-rather than to draft other legislation?

Who ensures that the draft law uses procedures and meets official standards, and does not conflict with other laws?

Who does research into the detailed details of a bill? and finally, how can institutions provide input and feedback to the right few people, and not to the wrong parties, the power to provide information to those involved in drafting bills - facts, theories, and the aspirations and demands of "various groups"? (Seidman).

In legislation where there are conflicting values and interests, there are two possible legal positions, namely as follows: (1) as a means of melting conflict (conflict oplossing), and (2) as an act that strengthens the occurrence of further contradictions, further (conflict versterking). This description shows that in a society that is not based on an agreement of values, the formation of law is always a kind of sedimentation of contradictions that exist in society.

Related to research on the formation of Qanuns in Aceh Province, it is almost the same as in the legislative process which must adjust to the process of forming laws or regional legal products, and in the process of forming it all begins with the preparation of several supporting documents or, among others, the initial draft draftqanun and academic texts.

In order for a Qanun to be accounted for from a scientific aspect, it is necessary to have an academic paper as an initial draft of the results of studies and research which contains regulatory ideas and material for certain fields of law, theoretically an academic paper is an inseparable part of compiling a Qanun draft , because it contains regulatory ideas and content material for certain Qanun fields that have been reviewed systematically, holistically, and futuristically from various scientific aspects. Academic manuscripts are also material for consideration used by the initiator of the Qanun to regional heads, because they contain the most rational arguments, both from a juridical, sociological, political and philosophical perspective, regarding the importance of drafting a Qanun.

Because there is no academic paper, almost all drafts of RanQanun, except when starting the drafting of the RanQanun related to the master plan, are compiled by the leading sector not using a certain method, for example using the Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) method, which includes: (1) identify clearly and precisely the target to be achieved from the issuance of the Qanun, (2) analyze whether the issuance of the Qanun can solve some or all of the problems that arise, etc. B. Problem Formulation.

From the above background, it is clear that in this article the following problems will be examined;

Is the formation of law through a legislative mechanism suitable and ideal for Regional Government in Indonesia?

Research Purposes

The research objectives in this article are:

To find out the ideal concept for the Regional Government in carrying out the process of forming legal rules in a regional capacity.

Research Methods

This study uses an empirical normative legal research approach, namely by examining legal principles to describe and explain a problem based on existing realities, and to complement the data obtained from library research.

Data Sources

Secondary Data

Secondary data is data obtained through library research. The collection is done by studying the literature and laws and regulations that are related to the problem under study.

Primary Data

Data obtained through field research, namely by using a questionnaire technique and interviewing respondents and informants.

Data Analysis

The data obtained from the research results were arranged systematically using qualitative analysis techniques with a sociological juridical approach or a sociological legal approach as one type of empirical approach. The sociology of law approach views law in its form as reality, behavior and action.

Argument

The existence of law is for human coexistence. Supposing that the law was related to other things, but in the end it would always be related to this life with humans. Thus, briefly it can be said that the law functions to serve and at the same time regulate life with humans (society).

In fact, the means to regulate life with humans (society) are not only monopolized by law (law). This can be read from Satjipto Rahardjo's opinion as follows: "If humans and social life take precedence, it is not important to make law the only means of regulating society". This is because evidence is often found that the law which is intended as a means of regulating the society "... also has the potential for criminogens". Since they are not the only means of regulating society, "On the other hand, there are non-legal means, such as informal social control, which often perform better than those indicated by law" (Satjipto, 2006).

Based on the explanation above, it can be argued that the process of forming law (legislation) is a relatively very important process as it is relatively important to see the process of implementation and enforcement of the law itself. This is because the process that occurs in the formation of the law will somehow also influence the process of implementing and enforcing the law. Mistakes in the legal formation process can have fatal consequences, because the erroneous law formation process can give birth to legal products that are criminogenic in social interactions.

T. Koopmans stated that the function of forming laws (laws and regulations) for now is increasingly important and very necessary. This is because in a state based on modern law (verzorgingsstaat) the main objective of legislation is not just to create a codification for the norms and values of life that have been deposited in society, but its purpose is broader than that, namely to create modifications in people's lives (Maria, 1998).

Koopmans' view points to the different general characteristics of statutory regulations (modern law) of the 19th and 20th centuries. Modern law of the nineteenth century is generally a feature of the statutory regulations of a codified liberal law state, while the laws of the twentieth century are more of a modified social welfare state legislation. Of course, for the present century the characteristics of modified legislation are still part of the objective of law formation.

Based on T. Koopmans' opinion, it can be argued that currently legislation is very important for a country based on modern law in conducting experiments in the framework of legal development. Legislation becomes full of burdens to be able to produce laws that are not only a vehicle for positivating the norms and values that are currently taking place in society, (Satjipto, 2003) but also full of burdens to carry out laws that are intended as a means of social engineering, as a means to support community development and national development. , and realizing social welfare.

Therefore, democracy has become a very influential and exalted term in practice, especially in the history of human thought about the ideal social-political-state order (Hendra, 2006).

UNESCO's 1949 study states: "probably for the first time in history democracy is claimed as the proper ideal description of all systems of political and social organizations advocated by influential proponents" (Miriam, 2005).

Slowly, some countries in the Gulf region have begun to open up to accept democracy - with all its adjustments - in the political system of their country. The centrality of the position of democracy is getting stronger along with the emergence of other concepts, such as human rights, civil society, and good governance, which in turn emphasize democracy as the best concept and assumption ever achieved by human thought (Hendra).

Jean Baechler argues that democracy does not only contain virtues, but it can also lead to fraud (corruption) in democracy. The main types of cheating in a democracy include political cheating, ideological cheating, and moral cheating (Baechler). Fareed Zakaria also suspects that in a democracy there may be deviations that originate from two things, namely (1) coming from elected autocrats, and (2) coming from the people themselves. Finally, the majority of people - especially in developing countries - often undermine human rights and corrupt existing tolerance and openness (Fareed, 2004).

Result and Discussion

Legal Formation Process

In a country that is built on the concept of democracy, it means that at the last level the people are the ones who determine the main problems regarding their lives. Included in this is to plan, formulate, determine, and evaluate policies made by the state, because those policies will determine the course of people's lives. Thus, a democratic state is a state that is organized based on the will and will of the people, (Curzon, 1998) or, when viewed from an organizational perspective, it is a form of state organizing carried out by and/or with the consent of the people themselves (Wayne, 1994).

Etymologically, the meaning of democracy does not matter much. However, as a concept both in the concept of politics and in the concept of law, the question arises about how to give the real meaning of sovereignty? This is because studies of political science, constitutional law, and international law show that this word sovereignty - even though it is a very fundamental definition - is full of contradictions.

Guided by the notion of legal positivism, Bentham and Austin saw the progressive role of the holders of sovereignty in legislation in directing society towards prosperity. This can be seen, for example, from Austin who views the correct goal of a government political sovereignty as "the greatest possible advancement of human happiness". Meanwhile, Bentham stated that the goal of legislation is "the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people". The views of the two scholars indicate the existence of happiness and welfare as much as possible as the goal and source of government action.

Locke calls this natural state the State of Liberty, which is a state of society that provides protection for human freedom (John, 1924). The government is formed with majority consent and is needed to protect the rights granted by nature. In this case, all citizens must agree to the government, which approval is only given to be subject to majority decisions/rules.

Rousseau's idea of a general will (la volontégénérale) was transformed in Germany into "pluralist sovereignty". This transformation is particularly evident in the thinking of George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. In Hegel's thought, the freedom possessed by humans is not in its a priori conception as rights derived from natural law, but as part of an ethical system of living together which is formed in the realm called civil society (Ashraf).

The concept of freedom in the context of civil society, according to Hegel, is not as political freedom or freedom belonging to citizens, but freedom that is owned by the bourgeoisie (bourgeois), which is related to economic status in a market-based society. In this context Hegel links the political and economic dimensions and tries to find a balance between the two, from which effective protection of individual liberty can be provided by means of a formal distribution of social forces (David, 2003).

Conceptually, modern democracy which contains the idea of the people as the owner of sovereignty in a country does not seem to contain too many problems. What actually raises an academic question mark is how ideally people's sovereignty is implemented in the empirical realm. Is people's sovereignty exercised directly, in the sense that all members of the community directly plan and decide all policies, or is people's sovereignty exercised indirectly, in the sense that such sovereignty is entrusted to elected people who are considered capable of representing the sovereignty of the people as a whole.

Legal regulations regarding people's participation in the administration of the country are subject to limitations and requirements, such as regarding age (in elections), education level, certain skills that must be possessed, mental health, involvement in banned organizations, status as a convict or the deprivation of political rights based on court decisions that have permanent legal force (inkracht van gewijsde). This explains that not all citizens can be categorized as sovereign people.

Framework for Ideal Concept of Regional Regulation Legislation

From all the descriptions and thoughts above, it can also be seen that the political configuration of Indonesian democracy which is based on democracy according to the four principles of Pancasila and the 1945 Constitution, which in its operative dimension can be shifted into elitism, undoubtedly needs to be given a new meaning. This new meaning means a shift from elitist to participatory. This is intended so that the operational framework of democracy according to the formulation of the four principles of Pancasila is back in accordance with the basic values of Pancasila itself as well as in line with the basic principles of democracy.

Based on this brief description, this study will then propose the ideal concept of Qanun legislation from a democratic perspective. However, it is necessary to show the imperfection of the final product of the legislation beforehand. No matter how good the planning and preparation in legislation, it must be realized that in the end it will produce imperfect products. This is even more so if the process is passed without proper planning and preparation and is full of various interests that are not in line with the public interest.

Basically, it is very unfortunate that there has been a systematic decline in the future of this customary law. If this condition occurs, then the "way of law" or using ROL, the Indonesian nation seems less enthusiastic in welcoming the world trend that respects diversity in implementing the ROL. Of course, what is undoubtedly done is to try systematically to present customary law parallel in the legislative process. Or at least, the principles of customary law are appointed and used as a reference in every legislation.

As recorded in history, the introduction of the Indonesian nation to modern law occurred when this country was colonized by the Dutch colonial government. The Dutch legal system with the Civil Law tradition was introduced and incorporated into Indonesia which was then mixed with the customary law tradition, through the concordance principle and the principle of unified law (eenheidsbeginsel). SoetandyoWignjosoebroto called this mixing process as a legal transplantation from a foreign (European) legal system into the middle of a typical colonial society legal system (Soetandyo, 1995). This transplantation process often creates problems. Can an Indonesian nation that has a customary law tradition be able to properly follow the tradition as prevalent in modern law which is basically not the original tradition?

The strong current development and development of law through this legislation also has constitutional justification. Article 20A paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution (amended) reads: "The House of Representatives has a legislative function, a budgetary function and a supervisory function". Thus the term legislation has become a constitutional terminology. This term also appears in Law no. 23 of 2014 concerning Regional Government, namely in Article 41 which reads "The Regional People's Representative Council has a legislative function, a budget function, and a supervisory function".

Basically, the written constitution and laws have formulated that legislation is one of the relatively important requirements for constructing laws in Indonesia. The famous idiom of wisdom from the Old Latin, namely: summum ius, summa iniuria (perfect law means perfect injustice/highest justice also means the highest injustice) is a warning in relation to the formation of laws which, although carried out in a mature and planned manner, certainly will not may produce perfect laws. Predictably, they are aware of the potential for injustice inherent in the formulation of law. According to Gustav Radbruch, the potential for imperfect laws to occur is due to the antinomies between the three legal ideals, namely: justice, certainty and benefit which are undoubtedly difficult to concretize in one legal formula (Achmad, 2002).

Meanwhile, a meta-juridical defect shows the connection of a legal product outside of juridical issues, such as its relation to politics, economics and socio-cultural. These meta-yuririds flaws usually start when people, for example, question: is the amount of the legal fine is economically realistic ?; in the political field, what if a legal product creates political instability ?; Is a law that is formed intended to carry out social engineering (social engineering) will not contradict socio-cultural? Viewed socio-culturally, it is not uncommon for a statutory regulation to be criminogenic. That is, a law with a "good" purpose, when applied can have the opposite effect.

The repressive law, the positivist-instrumentalist law, and the non-relational law are symmetrical with what Adam Padgorecki calls "authoritarian law". There are five characteristics of this authoritarian law, namely: first, its substance is binding unilaterally and changes according to the wishes of the authorities. Second, the rule of law is used as a cover in a clever way to cover up excessive power intervention.

Third, society's acceptance of the law runs in a false sense. Fourth, legal sanctions have the potential to cause social disintegration and social nihilism to spread uncontrollably. Fifth, the ultimate goal of law is institutional legitimacy that is free from the issue of whether it is accepted or not by the community (Brodjo, 2000).

In general, the provisions that require improvement include three things, namely: (1) concerning the publication of the RanQanun, (2) concerning the right of the public to participate in Qanun legislation, and (3) concerning the support of legal experts. Meanwhile, new provisions that need to be added include: (1) general determination of who is involved in Qanun legislation, (2) mechanisms for community involvement in Qanun legislation, (3) public consultation and examination of the RanQanun, (4) public complaints if their rights to participate in Qanun legislation are ignored by the regional legislature and executive, and (5) the formulation of sanctions for violators of the provisions of Qanun legislation.

After discussing the RanQanun, Commission I returned the draft RanQanun to Panmus. Furthermore, the Panmus submits the draft RanQanun to the DPRA Leadership and determines the schedule for the DPRA Plenary Meeting. The DPRA Leaders then conveyed the draft RanQanun at the DPRA Plenary Meeting. In the DPRA Plenary Meeting, the proposers were given the opportunity to provide an explanation of the proposed drafting of the draft RanQanun. After that, other DPRA members were given the opportunity to give their views and the Regional Head was given the opportunity to give their opinion. Furthermore, the proposers provide answers to the views of other DPRA members and the opinion of the Regional Head.

Before the DPRA member initiative proposal is decided to become the DPRA initiative proposal, the initiator will improve and also change the article formulations in the RanQanun based on the views of other DPRA members and the opinion of the Regional Head, so that the draft RanQanun is relatively more perfect than the initial draft. Based on the revised RanQanun, the DPRA later stated that it accepted the DPRA members' initiative to become the DPRA's initiative on an institutional basis.

From interviews with former members and leaders of the Aceh Province DPRA, an unusual incident emerged in the making of an academic paper. The academic manuscript should have been written by the initiator of RanQanun. However, what happened in the discussion of the RanQanun at the Aceh Provincial DPRA in 2014 and 2017 there were oddities, namely 4 (four) drafts of the RanQanun proposed by the Governor, but the one who took the initiative to make the academic paper was the Aceh Provincial DPRA.

After the DPRA Leadership conducts a brief research on the introductory note/letter along with its RanQanun, a Panmus Meeting is then held to determine the schedule for all stages from start to finish related to the discussion of the RanQanun set by the DPRA Leadership. The schedule for the discussion of the RanQanun is relative, which can be changed at any time by the DPRA leadership if there are any urgent matters after receiving suggestions, input and considerations from the Panmus and by the DPRA members themselves. A search of the schedule made by Panmus at the research location showed 2 (two) types, namely as follows: \ Sometimes the RanQanun discussion schedule made by Panmus scheduled the stages of a discussion that was written in detail starting from the Phase I Talks to the Stage IV Talks which were held in detail. it also details the meetings and activities conducted by the DPRA.

At times the schedule for discussing the RanQanun prepared by Bamus did not schedule in detail the stages of the discussion, but only scheduled meetings to be held by the local DPRA in order to discuss the RanQanun. Meanwhile, the time allocation used for the discussion of RanQanun in one trial period is very varied: 1) there are those who discuss RanQanun for only a few days it is immediately finished (some are only one day and some are more than a day but not more than one week); 2) there are also those that take months and have only been completed for up to one year; however, 3) generally it does not exceed 2 (two) months.

The schedule for the discussion of the draft Qanun at the DPRA is varied, some are long and some are a little short, calculated from the time of discussion since it was signed by the DPRA Leadership Decree to form a Discussion Committee whether the Commission, the Special Committee or the Legislative Body itself.

1. Qanun Number 8 of 2014 concerning the Principles of Islamic Sharia (Jadwal, 2014)

2. Qanun Number 11 of 2014 concerning the Implementation of Education (Jadwal, 2014)

3. Qanun Number 8 Year 2017 concerning Assistance for the Poor (Jadwal, 2017)

4. Qanun Number 11 of 2018 concerning Sharia Financial Institutions (LKS) (Jadwal, 2018)

Discussion Phase I and Phase II

In this stage, the Regional Head or one of the DPRA Leaders (who can also be the head of the Commission or the head of the Special Committee) on behalf of the DPRA submits an Explanatory Note related to the proposed RanQanun, which contains the main ideas and reasons why the RanQanun was drafted, and also explains. In detail the subject matter of RanQanun. Thus, the background of the interests and objectives of the DPRA or the Regional Head in compiling the RanQanun can be examined from the contents of the Explanatory Note of the RanQanun.

Submission of the Explanatory Note shall be conducted in an open DPRA Plenary Session. In general, those invited to attend and listen to the delivery of the Explanatory Notes came from various groups, namely: officials and heads of work units/SKPA, officials of Muspida/vertical agencies and BUMN, leaders of civil society, community leaders, the press.

The agenda carried out by the DPRA after the submission of the Explanatory Note is not the same. There is a Bamus DPRA who immediately forms a Special Committee with the task of carrying out intensive RanQanun discussions, as did the DPRA to form a Special Committee after the presentation of the General Views of DPRA factions which were carried out in Phase II Talks.

The DPRA Standing Orders stipulate that the task of discussing the RanQanun is the Commission in charge of the RanQanun material concerned or the Special Committee appointed. Before being determined in the Leadership Meeting in the Deliberative Council, the draft Qanun has been submitted to the Legislation Body for consideration and the main duties of the Legislation Body are: 1) Carrying out studies of the entire RanQanun 2) Providing considerations to the DPRA Leaders on the RanQanun to be discussed.

Then after receiving considerations from the Legislation Body, it was decided that the discussants of the draft qanun were discussed, and members of the Special Committee consisted of members of the Commission who represented all elements of the faction. Thus the membership of the Special Committee reflects the constellation of political power in the DPRA. The Special Committee which was formed in the phase I discussion immediately worked by making a special work schedule for the Pansus. Apart from that, the factions also started to hold a series of meetings with the preparation and preparation of the General Views (PU) which will be presented in the second level talks. Even though the faction is not one of the DPRA's apparatus, its vote is very decisive in whether or not a RanQanun becomes a Qanun. Thus, the PU faction will be given great attention by regional executives and regional legislatures, because the Faction's vote is a crystallization that reflects all the votes and strengths of the members in each DPRA faction. In this phase II discussion, there were several agendas carried out by the DPRA, namely as follows:

DPRA factions convey PU in the Plenary Session if the RanQanun from the executive, or the Regional Head expresses his opinion if the RanQanun is a DPRA initiative proposal; Formation of a Special Committee for DPRA that has not yet formed a Special Committee at the stage I discussions;

The Regional Head delivers answers to PU factions in the Plenary Session if the RanQanun from the executive, or the factions provide answers to the opinion of the Regional Head if the RanQanun is a DPRA initiative proposal.

The results of the review of the PU material fractions are basically still general in nature and have not specifically studied the substance of the RanQanun. In general, the PU faction contains: (1) requesting further explanation from the executive regarding the material contained in the RanQanun; (2) questioning the legal basis for the formation of the RanQanun; (3) questioning whether the drafting of the RanQanun has been carried out prior research; (4) questioning the performance of regional bureaucrats in dealing with gaps between facts in society and regulatory policies that have been implemented so far; (5) ask the executive to further improve the professionalism of its performance in providing guidance and supervision related to economic-socio-political problems that arise in society with regard to the issuance of Qanuns; (6) if the RanQanun is related to levies (regional retribution/regional tax), the faction requests that levies intended as a means to increase PAD do not burden the community; (7) stated that they are ready and support RanQanun to be upgraded to Qanun.

In this regard, it is necessary to state that although there are similarities in party ideology between the regional head and the DPRA chairperson in the research location, it does not necessarily mean that the same ideological factions simply agree with the regional head's RanQanun. It can be argued that in general, they ask for an explanation to question the relevance and readiness of the executive in implementing the Qanun.

In the next DPRA Plenary Meeting, the Regional Head will deliver Executive Answers to PU DPRA factions. The response of the Regional Head usually consists of: (1) general presentation related to the development of state administration at both the national and local levels, and (2) a special presentation, namely answering the questions and appeals from the factions in PU. Some of the answers are apologetic and some argumentative, supported by existing data. Regarding the faction's appeal, the regional head usually promises to improve his performance.

Discussion Phase III and Stage IV

After the Special Committee was formed at the previous discussion stage, the Special Committee then made a schedule of activities and agendas that focused on its task of completing the RanQanun discussion. The agenda of activities in the program schedule made by the Special Committee for the discussion of RanQanun in the research location is not the same as one another. Even in one DPRA, which at the same time made several Special Committee, each of which was formed based on the RanQanun material clusters, the agenda written in the schedule of each Special Committee could be different.

The results of the review of the Special Committee's schedule and reports of the work of the Special Committee regarding the agenda and activities of the Special Committee in discussing the RanQanun in all research locations can be presented as follows:

• The Special Committee conducts "work meetings" with agencies/work units/SKPD related to the RanQanun material being discussed.

• The Pansus conducts "public hearings" with parties who will be affected by the implementation of the Qanun (stakeholders).

• The special committee conducted field visits to certain locations to obtain input from the community.

• The special committee made a working visit (kunker) for a comparative study to other areas that already had Qanuns such as the RnaQanun being discussed by the DPRD.

• The Special Committee asked for help from universities to participate in conducting a review of the RanQanun being discussed.

• The Pansus conducts consultations both with provincial and central government officials who are related and have an interest in the guidance and supervision of Qanuns.

• The Special Committee held a public test of the RanQanun being discussed.

• The Pansus held a "special/internal meeting" which was only attended by members of the Pansus.

The choices of activities and agendas made by each Special Committee depend on the agreement of the Special Committee members. Comparison of DPRA Special Committee activities in research locations in order to discuss the RanQanun is shown in Table 1 below.

| Table 1 Comparison of Pansus DPRA Activities in Research Locations |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Response | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1 | Work Meeting with Stake holder | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | General Hearing | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 3 | Work Visit | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 4 | Academics review | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 5 | Government Consultation | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 6 | Public Test | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 7 | Comparative Study | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 8 | Harmonization | x | x | x | x | x | x |

From the explanation in Table 1, it appears that all mechanisms have been carried out by the DPRA Special Committee at the research location. It was during a work meeting with the local government work unit/executive team that the interaction of the political system actually took place. In this interaction there will be a process of bargaining and arguing in order to obtain a common perception between the Commission or the Special Committee and the Executive Team regarding the substance of the RanQanun.

By bargaining, arguing with each other, and influencing each other, it will be possible to reach agreements regarding whether the RanQanun is worth continuing, discontinuing, or postponing its discussion. If it is not feasible to continue or postpone the discussion, then at the end of the discussion it is recommended to reject and/or postpone the discussion. If it is feasible to continue, then the discussion will be continued by making an agreement to make improvements/refinements to the draft RanQanun, both concerning the systemic side, the formulation of the script, as well as regarding the substance.

The mutual influence of influencing, giving and asking, as well as mutual intervention which was full of intrigue in the discussion of the RanQanun was not "as hot" as the discussion of the RAPBA. As acknowledged by former members of the Special Committee and the leading sector, the discussion process carried out at this stage is more on their efforts to understand the needs and interests of the regions rather than those of factions/political parties, personal interests, and the interests of their constituents. Therefore, the interaction between the Pansus and the leading sector in the discussion of the RanQanun in the research location - apart from the RanQanun related to the problem of the length of office of the village head which received quite intensive attention from the village heads - seemed to be running calmly. There was no strong pressure from the Special Committee on the RanQanun proposed by the executive, except that they only wanted to gain an understanding of the intent and purpose of proposing the RanQanun in question, as well as its feasibility if it was later approved to become a Qanun.

The discussions between the DPRA Special Committee and the SKPA were generally relatively calm because the RanQanun discussed had no direct or indirect implications for the interests of the DPRA Special Committee. Therefore, in the discussion of the RanQanun there are no "special promises" given by the proposer so that the RanQanun is immediately approved.

Meanwhile, special/internal meetings are held in order to make a work plan, inventory problems, filter and formulate the results of input from the public obtained through public hearings and field visits, formulate the results of talks in the interaction of the political system with the executive which are held at work meetings, correct the formulation sentences in the article, amending and improving the substance of the article formulation, compiling conclusions and recommendations, and making a report on the work of the Special Committee to be submitted at the last plenary session. The conclusions and recommendations of the Special Committee were used as a reference for the factions in formulating the PA as well as a recommendation to the DPRA to accept or reject the RanQanun as a Qanun.

The former members of the Pansus and DPRA leaders who were interviewed gave answers that all the RanQanun being discussed must be published/socialized in order to seek input from the public. However, this opinion will be different if you trace the schedule of the Special Committee and the Report on the Work of the Special Committee. From the review, it turns out that the Pansus public hearings to obtain input from the relevant public (stakeholders) are sometimes scheduled, but sometimes not carried out.

To find out whether the DPRA published all of the RanQanun being discussed, Table 2 below describes the responses of respondents at the research location regarding the publication of the RanQanun.

| Table 2 Response to the Distribution of the Ranqanun |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Response | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1 | The Draft Qanun is Published | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | DrfatQanun no Publication | ||||||

The presentation of Table 2 informs that respondents who answered all published RanQanun (100%) and unpublished RanQanun (0%) indicate the percentage of appropriate answers.

The data exposure in Table 1 indicates a symptom similar to that carried out by regional executives when they were preparing the draft RanQanun, in which most respondents stated that not all drafts of the RanQanun were published. In fact, 14.93% of respondents who gave answers did not know/did not answer whether the RanQanun was published, indicating that the publication of the RanQanun being discussed by the DPRA was not widely spread and reached all levels of society.

In line with the publication of the RanQanun, it concerns the issue of public participation in the discussion of the RanQanun. Table 3 below is the respondent's response to the question whether they were invited by the DPRD to participate in the discussion of the RanQanun?

| Table 3 Participation of Respondents in the Discussion in DPRA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Response | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1 | Participate | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | No Participate | ||||||

Table 3 informs that only respondents (100%) at the location answered that they were always invited to participate by the DPRA in the RanQanun discussion.

Normatively, the role of respondents who come from civil society is as part of society - both as regulated in Article 53 UUP3 and in Article 139 paragraph (1) of Law no. 23/2014 on Regional Government - nothing more than just a party providing input in the process of preparing or discussing Qanuns. Thus, their position and role are not in a strategic position in the Qanun legislation.

This means that the participation/participation of the public in the deliberation of the RanQanun is highly dependent on the intention and willingness of the DPRA. If the DPRA intends to include the public, then invitations for that purpose have not yet been addressed to the majority of civil society. DPRA's argument is that it is impossible to involve the entire community in discussing the RanQanun. Therefore it is necessary to make subject elections that are thought to understand the subject matter and content of the RanQanun and which are considered to reflect the interests of the majority of the public.

With the model of determining criteria as carried out by the DPRA Special Committee at the research location, it has an impact on the limited public participation in the discussion of the RanQanun. If this is the case, then it can be argued that the principle of openness in the formation of the Qanun has not been fully implemented in the research location.

This is certainly in accordance with the previous data exposure in Table 12 which informs that the DPRA Special Committee public hearing in order to seek input from the public is only "occasionally" or means it is always carried out by DPRA when discussing the RanQanun. Even up to the "public test" of the draft RanQanun at the research location.

Why are the respondents' inputs sometimes not accepted? The reason for the Commission, the Special Committee was that some of the input from respondents was far from the substance of the draft Qanun.

The symptom of the unclearness of whether public input is accommodated in the Qanun is because the public sphere to participate in the Qanun legislative process is limited to public hearings and field visits. In fact, the two activities will be open if there is a will from the DPRA and the Executive Team to invite the public to participate in the deliberation of the RanQanun.

After the event, the community could no longer supervise the substance of RanQanun based on the aspirations they convey. This is because at the time the final draft of the RanQanun discussed in the internal committee meeting, which will be decided to become a Qanun, no longer requires public approval, for example through a public test or public consultation.

Basically, this condition of limited public space has been preceded by the DPRA Standing Orders in the research location, which does not clearly formulate the DPRA's obligations to accommodate and follow up on public input into the RanQanun that is being discussed. In fact, the absence of a formulation for public consultation and examination when the RaQanun will be stipulated as Qanun in the DPRA Standing Orders further weakens the public's bargaining position in Qanun legislation.

Working visits (kunker) with comparative study programs, although sometimes carried out, but almost always carried out by the DPRA Special Committee who is discussing the RanQanun. Indeed, not all special committee members conducted a visit/comparative study, like all DPRA special committee members at the research location when discussing the Protocol on Protocol Status did not carry out a kunker.

However, outside of the RanQanun, almost all DPRA Special Committee conducted a comparative study to other regions. In general, the justification that was built for these activities was in order to obtain input from other regions that already had allied Qanuns and also to compare the RanQanun material that was being discussed with the Qanuns of other regions which would later be used to improve the RanQanun.

In relation to public trials, not all DPRA Special Committee conducts public trials or public consultations on the RanQanun being discussed. This public examination and public consultation is carried out when the draft RanQanun is deemed perfect and ready to be brought up in Phase IV of the Discussion in order to make decisions on the intended RanQanun.

After the DPRA Special Committee felt that it was sufficient in discussing the RanQanun, the Special Committee then held a special/internal meeting to compile conclusions and make a report on the results of its work. The conclusions of the Special Committee are accompanied by the formulation of changes and improvements to the draft, and some contain only conclusions and recommendations whether or not the RanQanun becomes a Qanun.

The DPRA Special Committee always makes a written report and is formally submitted at the Plenary Session - some held the Plenary Session when it was still in the III discussion stage and some were delivered at the IV discussion stage before the PA Fractions - Even though all PA factions mentioned that the Special Committee had worked with good, but in the absence of a written Pansus report, it is difficult to know the truth of the Pansus that has worked well.

Based on the conclusions and recommendations of the DPRA Special Committee in its report, DPRA factions began to formulate the PA. For DPRA that has already held a Plenary Meeting at the stage III discussion in order to deliver the results of the work of the Special Committee, the PA Fraction is drawn up after the event, whose time is still in stage III discussions.

While the Special Committee submits a report on the work results of the stage IV discussion, the PA preparation is carried out at the discussion stage after the implementation of the Special Committee report.

This stage IV discussion was conducted in one DPRA Plenary Meeting which was open to the public which contained the following agenda: (1) submission of reports on the work of the Special Committee. This was mainly done by the DPRA, which previously (in phase III discussions) had not yet held a plenary meeting in the context of submitting a report on the work of the Special Committee; (2) submitting PA factions and/or DPRA members; (3) DPRA decision making whether to accept or reject the RanQanun into Qanun; and (4) the regional head's remarks on the DPRA decision making.

Indeed, not all of the RanQanuns discussed by the Special Committee were approved to become Qanuns. Related to this, there are several kinds of actions taken by the Special Committee, namely: (1) executives are asked to improve the RanQanun; (2) not continuing the discussion while still in the Special Committee discussion stage (stopping at the stage III discussion); and (3) postpone the discussion (only delivered at the stage IV discussion). However, the RanQanun that was not approved was not very much.

Some of the RanQanuns that were not and/or had not been approved when this research was conducted include:

During the plenary meeting, invitations from the general public who were present only passively listened and watched the Special Committee report their work, the factions conveyed the PA, the head of the meeting led the decision-making process to accept or reject the RanQanun as a Qanun, the Regional Head delivered a speech, and the leadership The DPRA and the Regional Heads sign the joint agreement.

In the plenary session, the draft RanQanun was not distributed, whether it was decided to be accepted or rejected by the DPRA as a Qanun. Thus, the invited public never knew what and how the substance/material of the RanQanun was decided to be accepted or rejected by the DPRA.

As previously mentioned, the conclusions and recommendations of the Special Committee which were conveyed in the plenary session always became the reference for the factions in their PA. If the Special Committee concludes and recommends that the RanQanun be accepted, then the factions' conclusions will not be different from the Pansus conclusions and propose to the DPRA Plenary Meeting to approve the RanQanun into Qanun.

Likewise, if the Special Committee concludes and recommends that the RanQanun is unacceptable, then the factions' conclusions will also not accept and propose to the DPRA Plenary Meeting not to approve the RanQanun as a Qanun. The acceptance and approval of the faction was accompanied by suggestions that needed to be carried out by the executive, such as the need for optimal socialization of the Qanun, immediately drafting implementing regulations, preparing supporting facilities for both institutions and personnel, and conducting intensive guidance and supervision so that the stipulated Qanun could be implemented. effective.

Based on the explanation above and the results of the analysis of the contents of the Final Views of each faction at the research location, in general it can be argued that the similarities and differences in the ideology of political parties between the DPRA Chair and the regional head are not significant in terms of support or rejection of the draft RanQanun proposed by the head. area. Support or rejection (in the sense of asking for a postponement of discussion) of the factions very much depends on the views of each faction on the substance of the RanQanun regarding whether or not it is supported or rejected as a Qanun.

Based on the decision approved by the Faction and all DPRA members, the event was continued with the speech of the regional head regarding the DPRA decision. In his remarks, the regional head welcomed with gratitude, joy, and gratitude for the good cooperation between members and the DPRA Special Committee and the executive, and would pay attention to the notes, suggestions, and hopes of the factions. Next, the DPRA Chair will write and sign several manuscripts as follows:

The DPRA's decision regarding the approval of the stipulation of the RanQanun to become a Qanun if it involves a general RanQanun. The signing of the DPRA Decree was made because the RanQanun could immediately be put into effect after being stipulated and promulgated by the Regional Head without having to be evaluated by the Governor first.

From all the descriptions of the process of forming a Qanun starting from planning, discussion, to the approval of the RanQanun, which is supported by the minutes of the DPRA trial, it can be argued that a RanQanun will be transformed into a Qanun with the interaction of the political system in it and requires very high time and cost. This is in accordance with the affirmation of Ann Seidman, et al., that a statutory regulation will not exist without a political decision process (Ann). Of course, these political decisions are based on the various interests of the actors involved in the Qanun legislation.

The Ideal Concept of Aceh Qanun Legislation

The formation of the Aceh Qanun in Aceh Province also follows the mechanisms stipulated in the Legislation and is in accordance with the Minister of Home Affairs Regulation Number 16 of 2006 concerning the Procedure for the Preparation of Regional Legal Products, which is a guideline, guidance and guidance for Regional Governments throughout the Republic of Indonesia in implementing the discussion procession from the first stage to the fourth stage discussion. All of these have finally been decided to become the stipulations on the draft Aceh Qanun to become the Aceh Qanun which will be promulgated in the Regional Gazette.

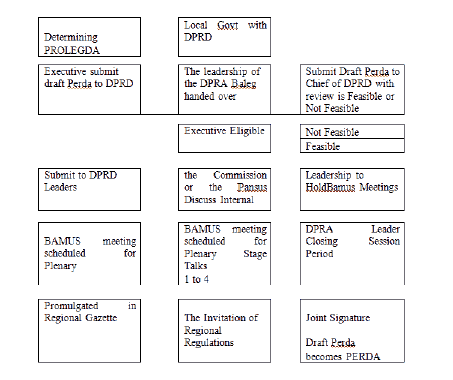

For this reason, it is necessary to describe the discussion scheme of a draft qanun into a qanun from the start to the end and in this study a concept for the deliberation process of a draft qanun is proposed that is right on target and saves more time and it is hoped that the goals and objectives will be achieved (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Scheme I: Permendagri Number 16 of 2006/Indonesia Law Number 23 of 2014

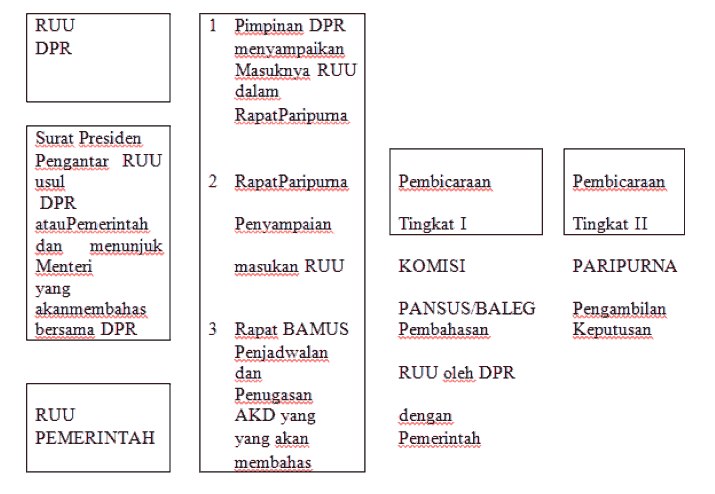

The legislative process that involves all political elements in the legislative space requires a very long time which sometimes seems very verbose but indeed there is a discussion mechanism in a regional legislative forum, even at the central level, almost the same procession needed in the discussion to the stipulation in a Decree of the Legislative Body (DPR-RI).

The discussion mechanism at the central legislative body is simpler in the process of discussion flow by shortening the space for movement in a series of discussions and the tendency for the draft to be mature before entering the DPR-RI institution which has been facilitated by the Secretariat General of the DPR-RI. Also in the scheme below can be explained in detail the discussion process in the DPR –RI building which is much shorter and saves time (Figure 2).

The flow of discussion at the central level legislative body is very simple and simple as illustrated in the schematic above, this shows that the process of forming a law at the government level does not show any friction and deep political intervention in the discussion, or illustrates how simple the process that occurs in the legislative body central level. Of course this is not the case because in every legislative institution there are always political nuances that participate and that cannot be avoided because it is the political space that will play a role when a rule or legal product is to be stipulated in the form of a law.

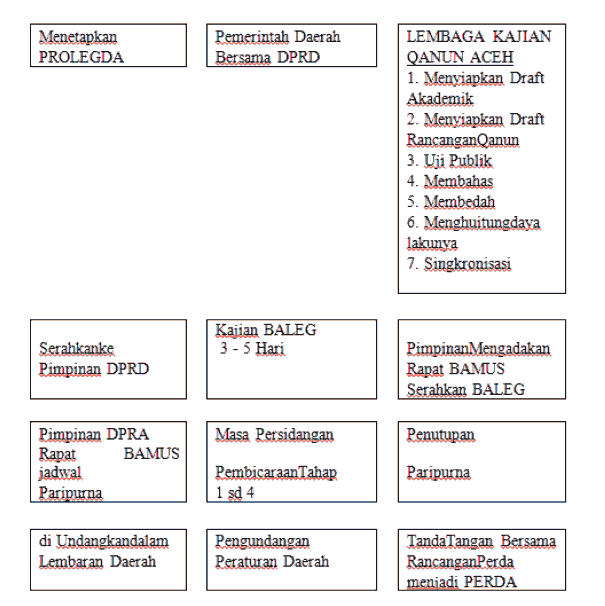

The model of all of them both from Permendagri Number 16 of 2006 and Law Number 23 of 2014 actually still provides a long time space in the discussion process and the author will try to introduce another model which is an ideal concept that is concluded from this research, and this ideal concept is This is a new thing regarding the results of the study from the Ann Siedman et al method, also considering the limitations of legal drafter in Aceh Province and with this model it is hoped that it will save more time in forming Aceh qanuns and will provide more definite value in the formation of Aceh Qanun.

The author will offer this concept to the Government of Aceh as a result of the study so far and the author sees it more precisely with the limitations of the legislative formation capacity of the legislative members, which only a few people are law graduates and law graduates who are members of the legislature are also not legal drafters of the law. -Invited and have never participated in legal drafting training conducted by the National Legal Studies Agency (BPHN) in Jakarta.

Reflecting on the scheme described by Joko Riskiyono, which describes a very simple discussion at the House of Representatives of the Republic of Indonesia (DPR-RI), perhaps this model can provide an overview and a breath of fresh air in the scope of the Regional Legislature wherever they are. The results of the thoughts of the whole study propose a conclusion by providing a solution by creating an initial institution (concept) that will formulate the entire draft qanun to be discussed together in the legislative body and the concept of the institution, namely as follows (Figure 3):

The scheme presented by this author will break the long time chain in the discussion to discuss a draft qanun and will facilitate the achievement of the results of the purpose in the proposed draft qanun.

Referring to the theory of Ann Siedmand et all, about the formation of law we get a match with the method that has been described in the scheme above, namely (1) the origins of the bill (a bill's origins), (2) the concept (the concept paper), (3) prioritizing, (4) drafting the bill, (5) research, and (6) who has access? (who has acces and supplies input into the drafting process). It is clear that the appropriateness of the interests in the application of the pattern of law -making in the new regions and institutions that we believe will be better able to work as much as possible and can avoid excessive political pressure.

References

- Achmad, A. (2002). Uncovering the Veil of the Law: A philosophical and sociological study. Holy mountain, Jakarta, hal. 72.

- Addis, A. (2008). Legislative drafting manual of Ethiopia. Justice and Legal System Research Institute/Justice System Administration Reform Program, 10-12.

- Ann, S. Op.Cit. hal. 42

- Ann, S., Robert, B., Seidman, & Nalin, A. (2001). Legislative drafting for democratic social change: A manual for drafters. Kluwer Law International Ltd., London, 24-26.

- Ann, S., Robert, B., Seidman, & Nalin, A. Op.Cit. 26- 30.

- Ashraf, M. (n.d). “Hegel’s crique of liberalism and social contract theories in the jena lectures”.

- Bergh, G.C.J.J. (1980). Learned Law: A Bird's-Eye history of European jurisprudence. Kluwer, Deventer. Lihat pada Ibid, hal. 3-4.

- Brian, Z.T. (2006). A general jurisprudence of law and society. Oxford University Press, Oxford New York, 107-112.

- Brodjo, S. (2000). “Repressive law and non-democratic legal production systems”. Legal Journal. 13, hal. 159.

- Curzon, L.B. (1998). Jurisprudence. Cavendish, London, 99.

- David, M. (2003). “Hegel’s corporation and associationalism: Democracy and the economy”. Makalah untuk Political Studies Association UK 50th Annual Conference, London, 10-13.

- Elizabeth, A., & Martin. (2006). Jonathan Law: A dictionary of law, (Sixth Edition). Oxford University Press, New York, 311.

- Fareed, Z. (2004). The future of freedom. translation by Ahmad Lukman, The Future of Freedom: The Deviations of Democracy in America and Other Countries. Ina Publikatama, Jakarta, hal. 121-122.

- Hendra, N. (2006). Democratic Philosophy. Earth Literacy, Jakarta, 1.

- Hendra, N. Op.cit.. hal. 2.

- The schedule for the discussion of the Draft Qanun begins with the DPRA Leadership Decree Number 14/PMP/DPRA/2017 dated 29 May 2017. After the discussion by Commission I chaired by Ermiadi Abdurrahman, ST. (Aceh Party faction) was then submitted to the DPRA leadership to be scheduled for the DPRA session, and included in the schedule for the V Session Period 23 to 24 November 2017. (7 Months)

- The discussion schedule for the Draft Qanun begins with the DPRA Leadership Decree Number 21/PMP/DPRA/2018 April 17, 2018. The discussion is finished by the Special Committee (Pansus) chaired by Drs. H. Jamaluddin T. Muku. (Democratic Party faction) was then handed over to the DPRA leadership to be scheduled for the DPRA session, and included in the schedule for the third trial period from 19 to 21 December 2018. (9 months)

- The schedule for the discussion of the Draft Qanun begins with the DPRA Leadership Decree No. 4/PMP/DPRA/2014 dated February 13, 2014. The discussion was completed by Commission E, chaired by Nurzahri, ST. (Aceh Party faction) was then submitted to the leadership of the DPRA to be scheduled for the DPRA session, and included in the schedule for the third trial period, September 24 to 26, 2014. (8 Months)

- The schedule for the discussion of the Draft Qanun begins with the DPRA Leadership Decree Number 8/PMP/DPRA/2014 dated 22 April 2014. After the discussion by Commission G, chaired by Tgk. H. Ramli Sulaiman (Aceh Party Faction) was then handed over to the DPRA leadership to be scheduled for the DPRA session, and included in the schedule for the Third Session Period from 24 to 26 September 2014. (5 Months)Jean, B. Democracy An Analytical Survey,National Book Trust, India, 246-254.

- Jeremy, B. (1996). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. J.H. Burns and H.L.A. Hart (ed.). Clarendon Press, Oxford; John L. Austin, 1954 The Province ofJurisprudence Determined and the Uses of the Study of Jurisprudence. Weidenfeld and Nicolson,London.

- John, H.M. (n.d). The civil law tradition. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1-6.

- John, L. (1924). Two treatise of government. JM Dent & Sons, London, 119.

- John, M., & Echols, D.H.S. (1995). English-Indonesian dictionary. Gramedia, Jakarta, p.353

- Maria, F., Indrati, S. (1998). Science… Op.Cit, p. 3.

- Maria, F., Indrati, S. (1998). Science of legislation fundamentals and its formation. Kanisius, Yogyakarta, 2.

- Miriam, B. (2005). Fundamentals of political science. Gama Media, Yogyakarta, p. 50.

- Peter, D.C. (1999). Comparative law in a changing world. Cavendish Publishing, London, 33.

- Satjipto, R. (2003). Other sides of law in Indonesia. Kompas Book Publisher, Jakarta, p. 162.

- Satjipto, R. (2006). Law in the universe of order, student readings for the doctoral program in law. Diponegoro University. UKI Press, Jakarta, p. 90-91

- Soetandyo, W. (1995). From colonial law to national law a study of socio-political dynamics in legal development for a century and a half in Indonesia (1840-1990). Raja Grafindo Persada, Jakarta, p. 1-8.

- Solly, M.L. (1995). Legal basis and techniques. Mandar Maju, Bandung, p. 1.

- Wayne, M. (1994). Elements of Jurisprudence. International Law Book Services, Kuala Lumpur, 32.

- Werner, M. (2006). Comparative law in global context, the legal systems of Asia and Africa. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 67.