Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Determinants of Job Satisfaction Among Academics at a Selected Institution of Higher Learning in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa

Nteboheng Patricia Mefi, Walter Sisulu University

Samson Nambei Asoba, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

Many studies have considered job satisfaction and its antecedents in the profit making sector. These studies have provided a number of factors that influence job satisfaction including autonomy, compensation, growth opportunities, leadership styles, task variety and so on. There are numerous factors that have been discovered to positively influence job satisfaction. Interest in job satisfaction arises from the fact that productivity and other favourable organisational outcomes such as service delivery and quality of outputs have been found to associate with job satisfaction. This study followed a quantitative approach based on a Likert questionnaire to collect data on the antecedents of employee job satisfaction within a Higher Education Institution (HEI) in South Africa. It was established that antecedents of job satisfaction in the HEI resembled closely those established in the literature. It is recommended that HEI should consider factors such as remuneration, task variety, work autonomy, good workplace relations and leadership styles to foster employee motivation.

Keywords

Job Satisfaction, Higher Education Institutions, Human Capital, Productivity

Introduction

There is a new imperative in the South African Higher Education sector in South Africa as in many other countries. This imperative relate to the greater need for higher education to play a leading role in addressing critical socioeconomic problems such as unemployment, societal transformation and the growth of entrepreneurship (Amadi-Echendu, Phillips, Chodokufa & Visser, 2016). In South Africa, stagnant economic growth and high unemployment rates have called for solutions from all key national institutions, including institutions of higher learning, to provide solutions (Urban & Richard, 2015; Malebana, 2016; Oni & Mavuyangwa, 2019). This call must be considered within the transformation discourse that arose in South Africa after the fall of the apartheid regime in 1994 and the need to equalize educational opportunities, reduce poverty and improve lives through education. This study focuses on the HE context whose success is largely dependent on the efficiency and effectiveness of human capital. This reliance on people competencies and skills makes it important to understand job satisfaction and its precedents. In a study of job satisfaction and occupational stress in the HE system in South Africa, Ngirande & Mjoli (2020) propound that workforce satisfaction should be understood as an important factor for effectiveness. Organisations need effective leaders and employees to achieve their objectives (Hamidifar, 2009).

Purpose of the Study

Given increased need for greater contribution of academics and Higher Education Institutions (HEI) to contribute to solving key national problems, there has also been greater need to ensure high job satisfaction among HEI employees. This need formed the basis for this inquiry on the determinants of job satisfaction among academics and other employees in the HEI. There are great demands on HEIs to ensure academic HODs are able to influence positive job satisfaction among members to ensure high performance. This in turn is expected to result in graduates who can contribute in solving current problems in South Africa (South Africa, Department of Higher Education and Training [DHET], 2017). Dlamini (2016) reports that 55% of students who enter the university will not complete their studies and less than 25% graduate on time. Exacerbated by the crisis related to the employability of graduates and their suitability in the labour market, this problem makes a call on HEIs to be tactful in delivering societal expectations. Furthermore, Toker (2011) asserts that most of the studies on employee job satisfaction have been related to profit-making industrial and service organisations. Kelali & Narula (2017) report that very few studies have identified the ideal leadership style for maximum job satisfaction, particularly in rural South African universities. In Despite there be prior research as well as significant findings on the determinants of job satisfaction, this study sought to put specific focus on a HEI. This will allow context specific determinants to be established and to be explained. The study, therefore, sought to explore the factors for job satisfaction at a HEI in one of South Africa’s rural provinces.

Job Satisfaction

O’Leary, Wharton & Quinlan (2009) argue that job satisfaction is generally conceived as an attitudinal variable that reflects the degree to which people like their jobs and is positively related to employee health and job performance. It also hinges on good relationships with staff and colleagues, control of time off and adequate resources. According to Gunlu, Akrsarayli & Percin (2009), to accomplish customer satisfaction, the job satisfaction of employees in the organisation is imperative. It should be noted that job satisfaction is a key factor in maintaining high performance and efficient service, which will directly increase the productivity of the organisation (Gunlu et al., 2009). Al-Ababneh & Lockwood (2007) state that managers are the core points of service production and therefore, their impact on the employees is very important. If managers are not satisfied and not committed to the organisation, their effectiveness in managing an organisation will be in question. There are three facets to job satisfaction (Gunlu et al., 2009), which can be classified as intrinsic, extrinsic and general reinforcement factors. To evaluate intrinsic job satisfaction, the key factors of ability utilization, activity, achievement, authority, independence, moral values, responsibility, security, creativity, social service status and variety must be addressed (Gunlu et al., 2009). For extrinsic job satisfaction, the factors to consider are advancement, company policy, compensation, recognition, supervision-human relations and supervision-technical. When intrinsic and extrinsic factors are summed up then general job satisfaction is formed (Gunlu et al., 2009). According to Toker (2011), most of the studies on employee job satisfaction have related to profit-making industrial and service organisations. There has been a growing interest in job satisfaction of employees in HEIs. Toker (2011) further indicates that the reasons for this increasing interest is the reality that HEIs are labour intensive, their budgets are predominantly devoted to personnel and their effectiveness is largely dependent on their administrative and academic staff.

Determinants of Employee Job Satisfaction

According to Abdulla, Djebarni & Mellahi (2010), the literature on job satisfaction can be divided into two groups—the content perspective which approaches job satisfaction from the perspective of needs fulfilment, and the process perspective which emphasises the cognitive process leading to job satisfaction. Abdulla, et al., (2010) indicate that these perspectives can be grouped into two broad categories namely demographic and environmental factors, which play a role in determining employee job satisfaction. Demographic factors are attributes of an individual, such as age, race, gender, education level, cultural influences and work experience. Environmental factors are characteristics of the immediate job, task significance, autonomy and interaction with co-workers (Abdulla et al., 2010). According to Sengupta (2011), when considering employee satisfaction, demographic variables should be considered to comprehend thoroughly the possible factors that lead to job satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Sengupta (2011) adds that demographic characteristics comprise factors that define individuals even before their entry into the workplace, such as gender, age, marital status, education level as well as other factors related to their work experience, such as job level, shift work and years of experience.

Methodology

In this study, employee job satisfaction was viewed as a construct that possesses both cognitive and behavioural dimensions. In other words, there was recognition that employee job satisfaction is an attitude with both latent and manifest elements. The study was based on the philosophy that employee job satisfaction is an attitude and its analysis is within the area of attitudinal enquiries. The assessment of attitudes has largely been associated with Rensis Likert whose publications on the measurement of attitudes have been instrumental in the design of attitudinal researches. Greenberg (2011) recognised that job satisfaction has followed a dispositional model, a value theory as well as a social information processing theory. This paper was premised on the social information theory which argues that job satisfaction arises from the nature of social interactions among organisational members. It was believed that the level of employee job satisfaction can be measured using Likert scales whereby employees assess themselves and rate their level of satisfaction on the scales. As a result the study was quantitative and it followed a survey design whereby a Likert self-response questionnaire was issued to all the employees at an academic department at the selected HEI. The selection of both the HEI and the department was effected following a convenience sampling strategy. Convenience sampling strategies involves the selection of participants based on convenience criteria such as availability, cost and proximity. A 5-point Likert-type scale was used, which asks respondents to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with a series of statements about a given subject (Saunders, Lewin & Thornhill, 2009). In the current study, 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree and 5= strongly agree. There were 10 academic departments at the HEI, implying that there were also 10 academic HODs at the HEI. The total number of staff under the leadership of the 10 HODs was 80. Of these 80 employees, 65 (n=65) responded to the questionnaire that was administered, which equates to a participation rate of 81%, which suggests that the study was interesting and attractive to the employees. This supports the notion in existing literature that leadership remains one of the most popular topics in the field of management.

Discussion of Findings

Biographical Information of Respondents

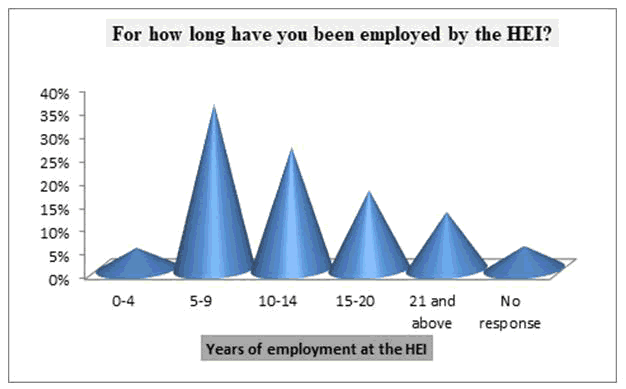

Tenure of employment at the HEI

This demographic variable considered the number of years of employment that the respondents had at the HEI under investigation. Figure 1 shows the percentage of employees found in the five categories of years of employment that were formulated for the study. As shown in Figure 1, the majority (37%) had been employed by the HEI for the past five to nine years. This should be considered in line with Wickramasinghe & Kumara (2010), who argue that tenure is the length of time an individual has worked in a specific job. The literature suggests that being in a job for only a short period could influence the individual’s intention to leave the organisation because of low job satisfaction and organisational commitment. The chief argument is that as the period of employment becomes longer, there is a tendency for improved job satisfaction. As shown in Figure 1, the lowest period of employment was less than four years.

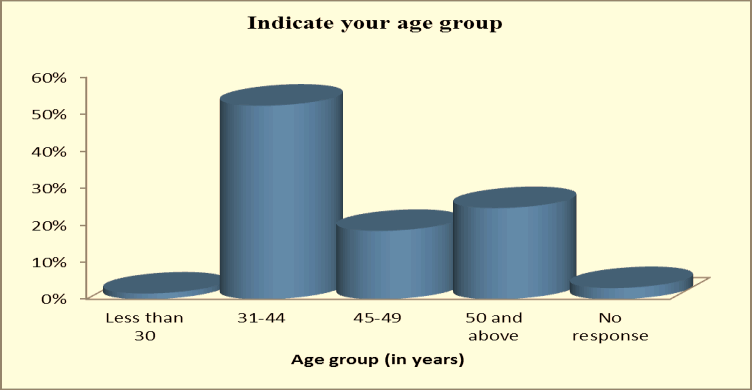

Age Groups

The age group of the respondents was another demographic variable considered. As shown in 2 below, the majority (55%) of the respondents were within the 31 to 44 year age group, the fewest were below the age of 30 (2%) and 40% were in the 45 to 49 year age group. Respondents of 50 years of age and over made up 25% of the study sample. According to Sengupta (2011:103), numerous studies suggest that a positive relationship exists between job satisfaction and age. Early bivariate and multivariate studies (Rhodes, 1983) indicate a positive linear relationship between age and job satisfaction up to the age of 60 years. On the other hand, Herzberg, et al., (1959), cited by Clark, et al., (1996) states that job satisfaction is U-shaped in age, with higher levels of morale among young workers, which declines after the novelty of employment wears off and boredom with the job sets in.

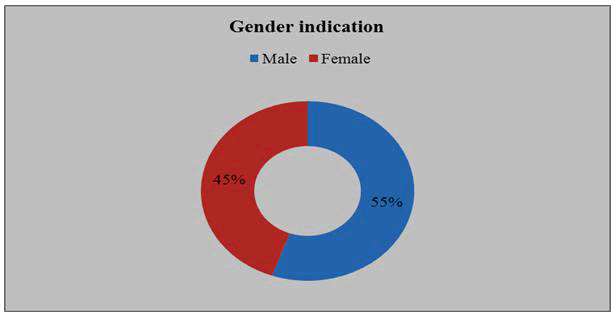

Gender Distribution of Respondents

More females (55%) than males (45%) participated in the study, as illustrated in Figure 3 below. Gender has always been an important factor in job satisfaction research. A number of researchers have examined the relationship between gender and job satisfaction. However, the results of the many studies are contradictory and inconclusive. Some studies found women to be more satisfied than men and others have found men to be more satisfied than women (Westover, 2012). Westover (2012) was among the first to fully examine gender differences in job satisfaction and found few differences between men and women in the determinants of job satisfaction when considering job characteristics, family responsibilities and personal expectations.

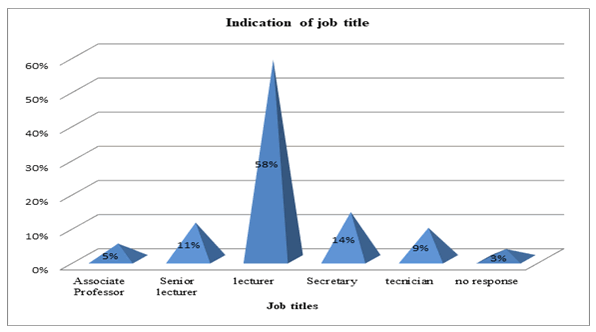

Job Titles

In academic institutions, academic HODs have several categories of subordinates whom they lead, oversee and influence. The study considered the job titles of the respondents to understand their roles that they play at the HEI, as shown in Figure 4. It is evident that the majority of them (55%) were lecturers, while there were a few associate professors (5%) and technicians (9%). Research indicates the relationship between the nature of a job and job satisfaction as significant. Work is the title of social prominence and seems to be a way for satisfying the social desires of citizens (Saif et al., 2012). Employees that carry out tasks that require high proficiency, selection, independence, reaction and job significance skills are reported to have a greater level of job satisfaction than their counterparts who perform responsibilities that are low on those attributes. Expressiveness is found to relate positively to job satisfaction (Saif et al., 2012). Workers tend to choose jobs that allow them to employ their proficiencies and aptitudes and offer a diversity of tasks, autonomy and responses on how well they are doing (Malik, 2010).

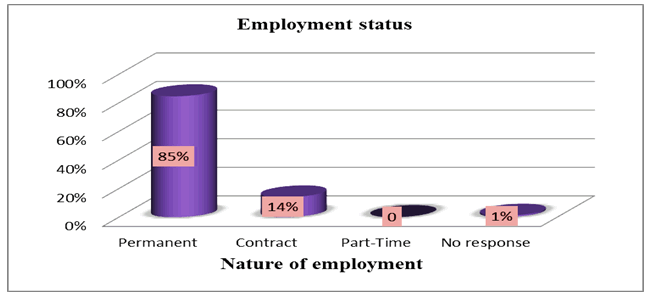

Status of Employment

Figure 5 shows the status of employment of the respondents. Employment was considered permanent, contract or part time. Permanent employment respondents returned an 85% result, 14% were contract employees and there were no part-time employees. The status of employment is often associated with variables such as pay, promotion and general status, which have been found to affect job satisfaction.

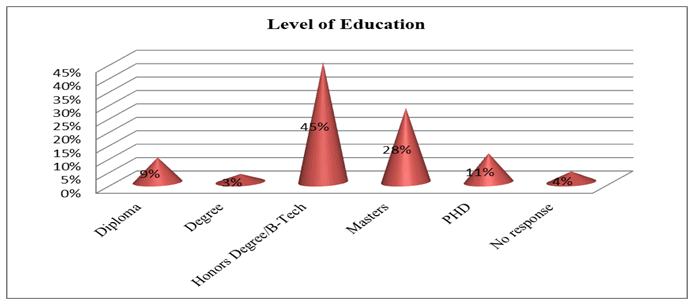

Level of Education

Another demographic variable that was considered in this study is the education level of respondents, shown in Figure 6. A significant number of respondents held an Honours or a Bachelor of Technology degree (45%), 28% had attained a Master’s Degree and 14% had achieved a PhD level. The literature confirms that employee satisfaction differs in relation to the level of education. The level of education influences a person’s work-related expectations in that rewards and responsibilities will change as the level of education increases (Sengupta, 2011).

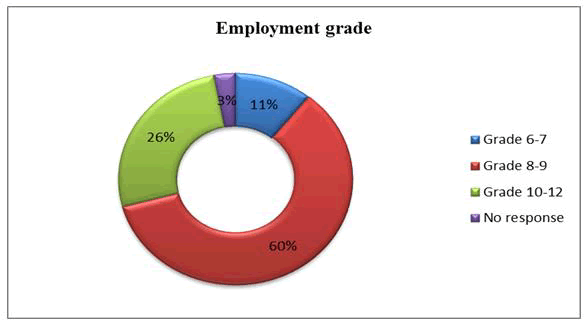

Employment Grade

Employment grades tend to be associated with benefits, which affect the work life of employees. Figure 7 illustrates that the majority (60%) of the employees were in the Grade 8-9 category, 26% were in Grade 10-12, while 11% fell within the 6-7 employment grade.

Determinants of Employee Job Satisfaction at the HEI

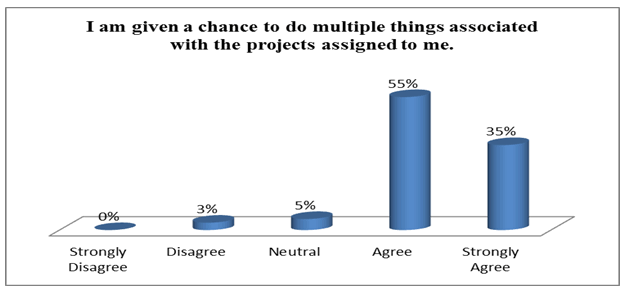

Task autonomy and multi-tasking as antecedents of job satisfaction

Respondents were enquired on the degree to which the employees were allowed to do multiple tasks associated with projects assigned to them. Chen, et al., (2006) suggests that the nature of the work and tasks affect job satisfaction. The literature seems to suggest that if subordinates are given a chance to do multiple tasks within their projects, it can help promote job satisfaction. Figure 8 shows a combined 90% of respondents agreed (55% agreed and 35% strongly agreed) that they are given a chance to do multiple things associated with projects assigned to them. This implies that these employees are satisfied by their jobs.

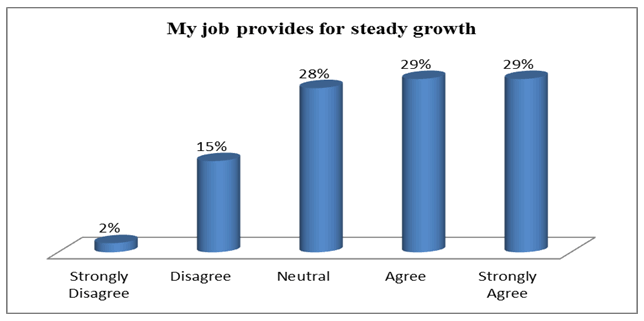

Opportunities for Growth as Antecedents of Employee Job Satisfaction

Theorists such as Maslow (1943); McClelland (1961) believe that growth, achievement and self-actualisation are predictors of job satisfaction. The general position in the literature is that the provision for growth opportunities is essential in influencing employee job satisfaction. In line with this, respondents’ perceptions on the opportunities for steady growth that is associated with their jobs are indicated in Figure 9. Of the 65 respondents, 29% strongly agreed that their jobs provide for steady growth and a further 29% agreed with the proposition. A significant numbers of respondents remained neutral (28%), 15% disagreed and 2% strongly disagreeing with the statement. This shows a general perception among the respondents that their jobs do offer opportunities for growth. Furthermore, this implies that the respondents could be satisfied by their jobs.

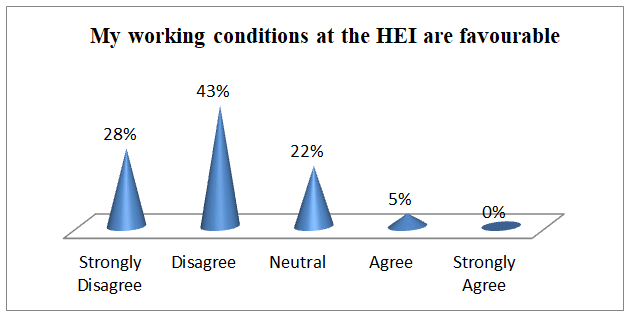

Working Conditions as Determinants of Job Satisfaction

The Job Characteristics Theory of Hackman & Oldham (1975) is well known and has been supported significantly as a way of understanding employee job satisfaction. Statement 22 of the questionnaire sought the respondents’ perceptions of whether working conditions at the HEI were favourable. The results are illustrated in Figure 10. A very significant combined 71% of the respondents disagreed (43% disagreed and 28% strongly disagreed) that the HEI offered favourable working conditions. Only 5% of respondents agreed with the statement, while 22% remained neutral. These results seem to suggest that job satisfaction is low when working conditions are considered.

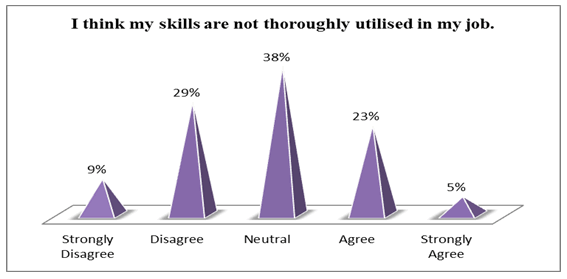

Skills Utilisation as a Determinant of Job Satisfaction

From the literature review, the full utilisation of a person’s skills is fulfilling and considered as a key determinant of job satisfaction. Consequently, jobs that ensure the full utilisation of an employee’s skills tend to result in greater employee satisfaction than those that do not adequately utilise their skills. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement that their skills are not thoroughly utilised. Figure 11 shows that the majority of the respondents (38%) remained neutral, while a combined 38% disagreed with the statement (29% disagreed and 9% strongly disagreed). However, 5% strongly agreed and 23% agreed, believing that their skills were not utilised in their jobs. The results suggest that more respondents experienced job satisfaction than dissatisfaction.

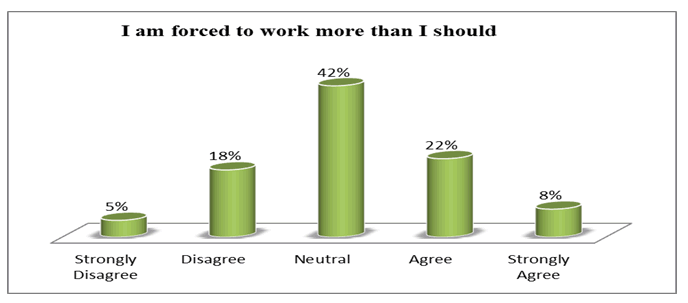

Forced Work and Job Satisfaction

While forced work does not align with the ethics and morals of a democratic South Africa, it also cannot be associated with employee job satisfaction as it goes against a number of established factors and predictors of job satisfaction. The questionnaire was designed for respondents to indicate the level at which they feel that they are forced to work more than they should. As shown in Figure 12, the majority (42%) were neutral while of the balance of respondents a combined 30% agreed with the statement and a combined 23% disagreed. The conclusion was that most respondents were unsure about their situation but there was a slight inclination towards job dissatisfaction.

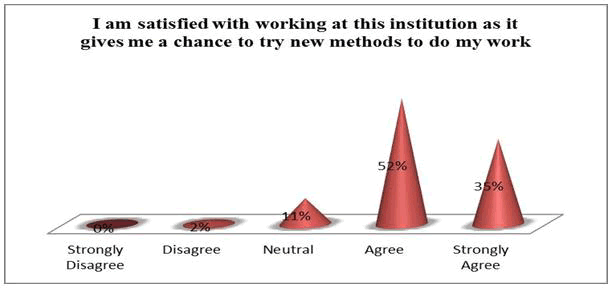

Provision of a Chance to Try New Methods to Do Work At the HEI

The respondents were required to provide their perceptions on whether they were given the chance to try new methods of doing work at the HEI. Figure 13 presents the findings. It is clear that the majority (52%) agreed, while 35% strongly agreed. Only 2% disagreed with the statement, while 11% remained neutral

Figure 13: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At This Institution as It Gives Me A Chance to Try New Methods to Do My Work

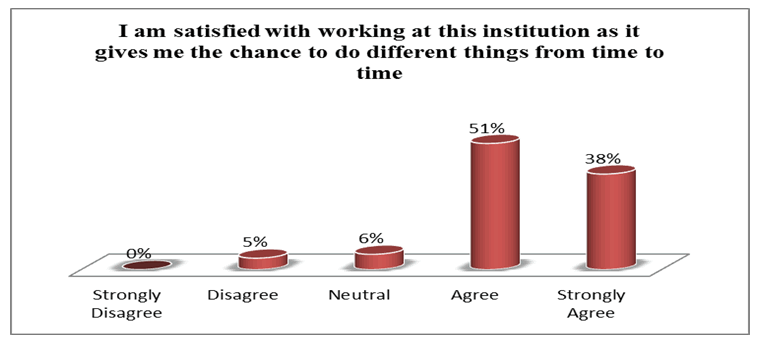

Work Variety

A combined 89% of the respondents agreed (51% agreed and 38% strongly agreed) that they were satisfied with working at the institution as it provided them with the chance to do different things from time to time. While 6% of respondents remained neutral, a mere 5% disagreed with the statement. The results are illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At Institution As It Gives Me The Chance to Do Different Things From Time to Time

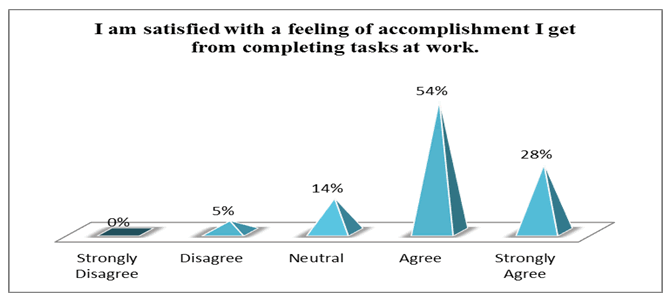

Positive Feelings of Accomplishment

As seen in Figure 15, a very significant 54% of respondents agreed and 28% strongly agreed that the feeling of accomplishment they derived from completion of tasks at work was satisfying. Only 5% disagreed with the statement, while 14% remained neutral. These results are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With A Feeling Of Accomplishment I Get From Completing Tasks At Work

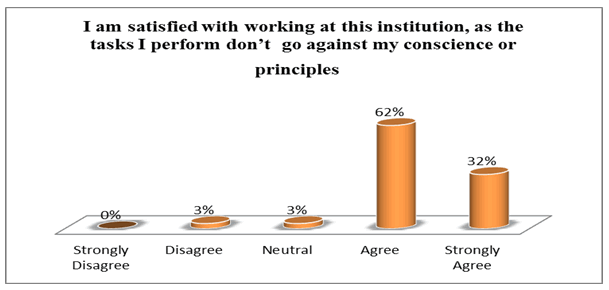

Work Ethics and Morality

The literature review chapters established that some employees are satisfied by performing tasks which align with their own or societal principles and conscience. The questionnaire required respondents to indicate their level of agreement on whether they are satisfied by performing work that aligns with their conscience and principles. As can be seen from Figure 16, there was a very significant combined 94% of respondents who agreed with the notion (32% strongly agreed and 62% agreed), while a mere 3% disagreed and 3% remained neutral.

Figure 16: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At This Institution, As The Tasks I Perform Do Not Go Against My Conscience or Principles

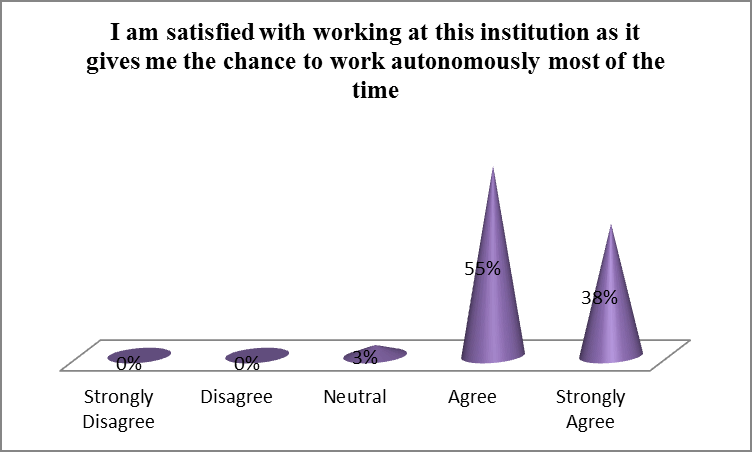

Work autonomy

As shown in Figure 17, most of the respondents (55%) agreed and 38% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with working at the HEI because it allowed them to work autonomously most of the time. No respondents disagreed and only 3% opted to remain neutral.

Figure 17: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At This Hei As It Gives Me The Chance To Work Autonomously Most Of The Time

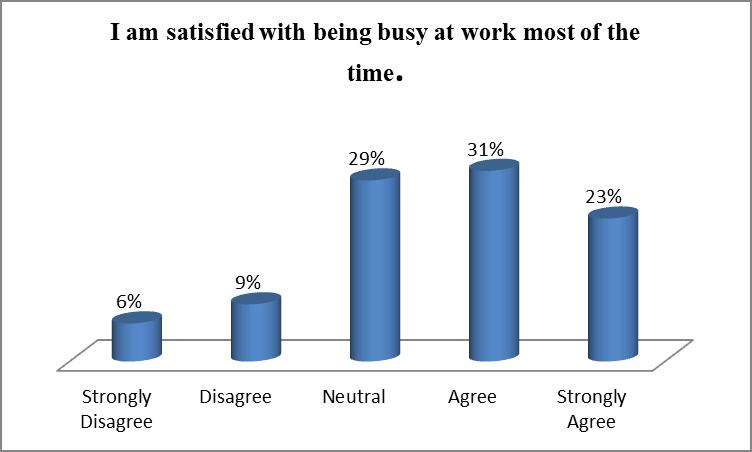

Busy Schedule of Work

Even though the majority (31%) of the respondents agreed that they were satisfied with being busy at work most of the time and 23% of them strongly agreed, many respondents remained neutral (29%). Only 9% disagreed and 6% strongly disagreed with this statement. These results are illustrated in Figure 18.

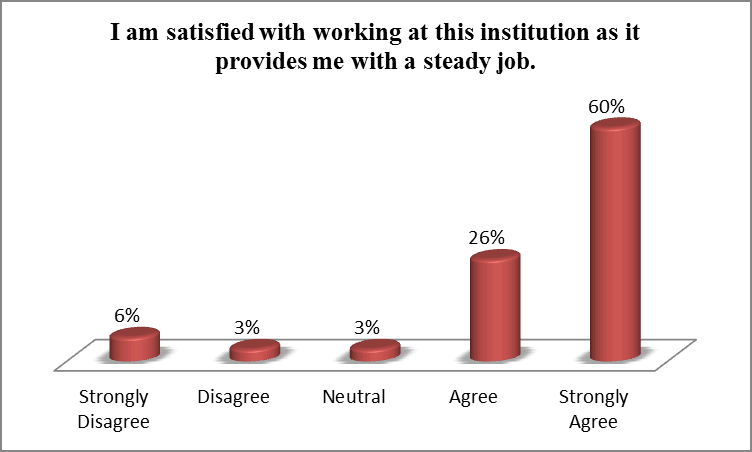

Job Security

As shown in Figure 19, job security was a major factor in employee job satisfaction. A very significant combined 86% of respondents agreed (60% strongly agreed and 26% agreed) that job security increases their job satisfaction. A mere 6% strongly disagreed and 3% disagreed with the statement, while 3% remained neutral.

Figure 19: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At This Institution As It Provides Me With A Steady Job

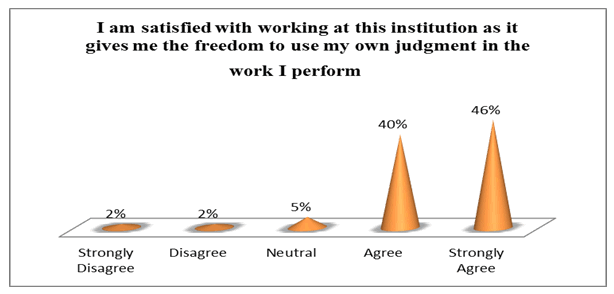

Freedom to use Own Judgement

Satisfaction through freedom to use own judgement was well supported, as shown in Figure 20. The majority (46%) of the respondents strongly agreed and 40% agreed that they were satisfied with working at the institution as it offers them the freedom to use their own judgement. A mere 2% of the respondents disagreed with the statement and 5% remained neutral.

Figure 20: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At This Institution As It Gives Me The Freedom To Use My Own Judgment In The Work I Perform

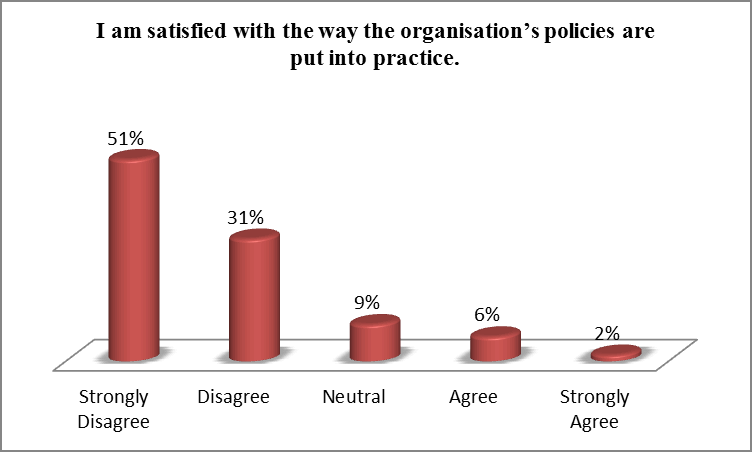

Organisational Policies

As shown in Figure 21, there was general disagreement that organisational policies that are practised at the HEI lead to job satisfaction. An overwhelming combined 82% of respondents disagreed (51% strongly disagreed and 31% disagreed) that they were satisfied by the way organisational policies were being put in practice at the HEI, 9% were neutral while only 6% agreed and 2% strongly agreed.

Figure 21: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With The Way The Organisation’s Policies are Put Into Practice

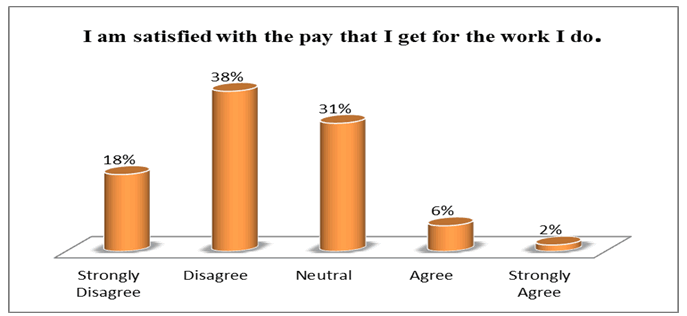

Pay

The majority (38%) of the respondents disagreed and a further 18% strongly disagreed with the proposition that they are satisfied with the pay that they get for the job that they do. A significant 31% of respondents remained neutral on this, while only 2% strongly agreed and 6% agreed. These results are shown in Figure 22.

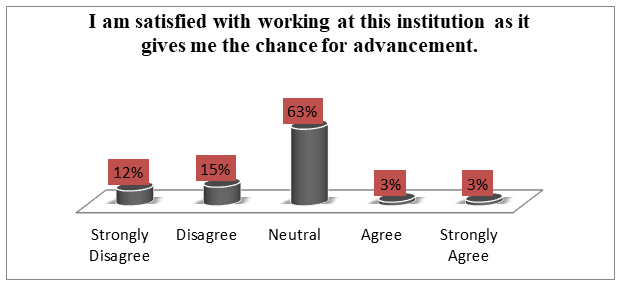

Opportunities for Job Advancement

Respondents’ level of agreement that they were satisfied with working at the HEI because it gave them chances of advancement. As seen in Figure 23, an extremely high number of respondents opted to remain neutral (63%) on this statement. Respondents who disagreed comprised 15% and 12% strongly disagreed, while only 3% agreed and 3% strongly agreed with the statement. The results suggest that respondents are generally unsure of job advancement opportunities at the HEI, a situation which would not encourage job satisfaction.

Figure 23: Responses on - I Am Satisfied With Working At This Institution As It Gives Me The Chance for Advancement

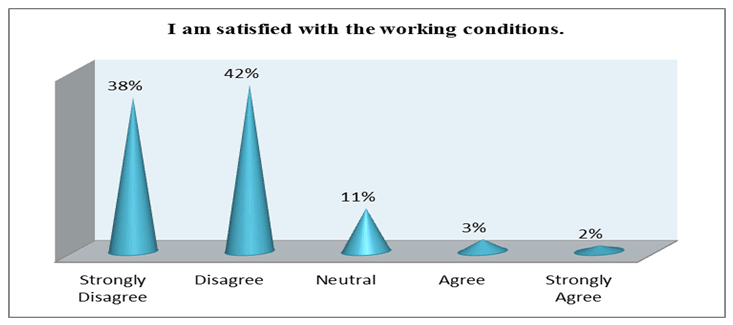

Working Conditions

The role of working conditions in job satisfaction was investigated through Statement 36. The results as presented in Figure 24 show that most of the respondents (42%) disagreed and a further 38% strongly disagreed with the statement that they were satisfied with working conditions at the HEI. Neutral responses comprised 11%, while 3% agreed and 2% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the working conditions.

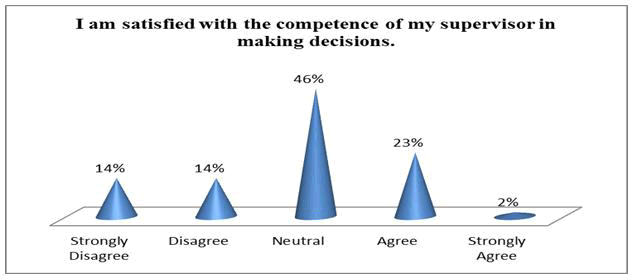

Competence of Supervisor in Making Decisions

The majority (46%) of the respondents were unsure whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement that they were satisfied with the competence of their supervisors in making decisions. A combined 25% of respondents were satisfied with the competence of their supervisors in making decisions, as opposed to a combined 28% who were not satisfied. The results are illustrated in Figure 25.

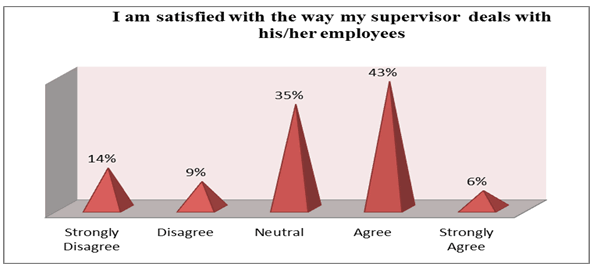

Supervisor Interaction with Subordinates

There was general agreement that the respondents were satisfied by how their supervisors dealt with subordinates (43% agreed and 6% strongly agreed). Figure 26 further shows that 35% of respondents remained neutral, while 9% disagreed and 14% strongly disagreed with the statement their supervisors dealt with subordinates in a satisfactory manner.

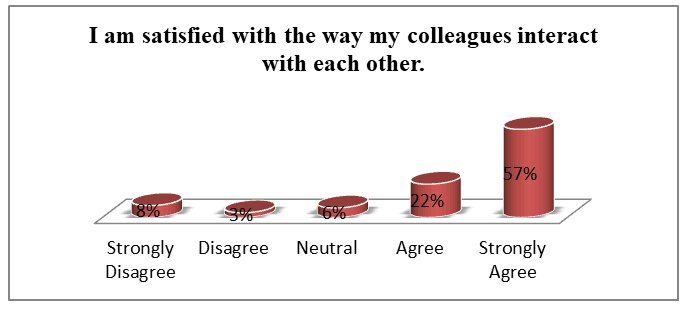

Interaction with Colleagues

As shown in Figure 27, 57% and 22% respectively strongly agreed and agreed that they were satisfied with the way their colleagues interacted with them and others in the workplace, while 6% were neutral, 3% disagreed and 8% strongly disagreed.

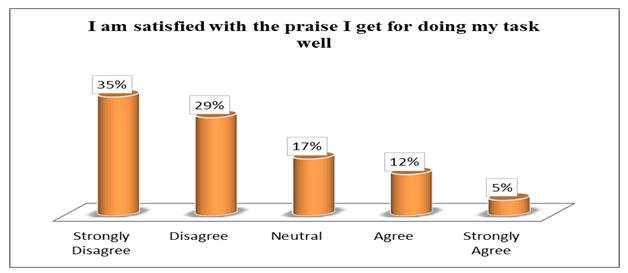

Praise and Recognition for Work Done

The last statement to assess the extrinsic rewards that led to job satisfaction focused on whether respondents felt satisfied with the praise they received for doing tasks well. The results as shown in Figure 28 show that the majority (35%) strongly disagreed, 29% disagreed, 17% were neutral to the statement, while 12% agreed and 5% strongly agreed.

Conclusion

The evidence collected in this study suggests that the employee/job satisfaction relationship at the HEI involves a matrix of several factors which are linked to those found in the literature. Factors such as praise and recognition, autonomy to execute new work methods, job security and so forth appeared critical in determining the employee job satisfaction. The studies have found that employee job satisfaction involves a number of biographical and psychological elements. HEIs should consider the factors mentioned in this study as essential in improving the quality of graduates, educational outcomes and ensuring that institutions of higher education contribute to solving high unemployment and social inequalities in South Africa.

References

- Amadi-Echendu, A.P., Phillips, M., Chodokufa, K. & Visser, T. (2016). Entrepreneurial Education in a Tertiary Context: A Perspective of the University of South Africa. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4), 21-35.

- Abdulla,J., Djebarni, R. & Mellahi, K. 2010. Determinants of job satisfaction in the UAE. A case study of the Dubai Police. Personnel Review, 40(1),126-146.

- Al-Ababneh, M., & Lockwood, A.J. (2007). The influence of managerial leadership style on employee job satisfaction in Jordanian resort hotels.

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., & Herrington, M. (2020). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 report: Igniting start-ups for economic growth and social change. Cape Town: University of Stellenbosch Business School.

- Chen, S.H., Yang, C.C., Shiau, J.Y. & Wang, H.H. (2006). The development of an employee satisfaction model for higher education. TQM Magazine, 18(5),484-500.

- Clark, A., Oswald, A.J., & Warr, P. (1996). Is job satisfaction U-shaped in age? Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 69(1), 57-81.

- Dlamini, R. (2016). The global ranking tournament: A dialectic analysis of higher education in South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), 53-72

- Gunlu, E., Akrsarayli, M. & Percin, N.S. 2009. Job satisfaction and organisational commitment of hotel managers in Turkey. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(5), 693-717.

- Hackman, J.R., & Oldham, G.R. (1980). Hackman and Oldham job characteristics model.

- Hamidifar, F. (2009). A study of the relationship between leadership styles and employee job satisfaction at Islamic Azad University branches in Tehran, Iran. Unpublished thesis. Graduate School of Business, Assumption University, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley.

- Kelali, T. & Narula, S. 2017. Relationship between leadership styles and faculty job satisfaction (a review-based approach). International Journal of Science and Research (IJRS).

- Malebana, M.J. (2016). Does entrepreneurship education matter for the enhancement of entrepreneurial intention? Southern African Business Review, 20, 365-387.

- Ngirande, H. & Mjoli, T.Q. (2020). Uncertainty as a moderator of the relationship between job satisfaction and occupational stress, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 46(1),1676-685

- O’Leary, P., Wharton, N., & Quinlan, T. (2009). Job satisfaction of physicians in Russia. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 22(3), 221-231.

- Oni, O., & Mavuyangwa, V. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions of students in a historically disadvantaged university in South Africa. Acta Commercii, 19(2), 667-674

- Rhodes, S.R. 1983. Age related differences in work attributes and behaviour. A review and conceptual analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 93(2), 328-367.

- Saif, S.K., Nawaz, A., Jan, F.A., & Khan, M.I. (2012). Synthesizing the theories of job satisfaction across the cultural/attitudinal dimensions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(9),1382-1396

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. (5th Edition). New York: Pearson Education.

- Sengupta, S.S. (2011). Growth in human motivation: Beyond Maslow. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47,102-116.

- South Africa. (2017). Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Research agenda 2017-2020. Pretoria: Government printers.

- Toker, B. (2011). Job satisfaction of academic staff: An empirical study on Turkey. Quality Assurance in Education, 19(2), 156-169.

- Urban, B., & Richard, P. (2015). Perseverance among university students as an indicator of entrepreneurial intent. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(5), 263-28

- Westover, J. 2012. Personalized pathways to success. Leadership, 41(5), 12-14, 35-36.

- Wickramasignhe, V. & Kumara, S. 2010. Work related attitudes of employees in the emerging ITES-BPO sector of Sri Lanka. An International Journal of Strategic Outsourcing, 3(1), 20-32.

- Greenberg, J. 2011. Behavior in organizations. 10th ed, Global edition. Harlow: Pearson