Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Do Brand Familiarity, Perceived Trust and Attitude Predict Stock Investment Decision Behavior

Shahab Aziz, Bahria University

Noor Azam Samsudin, Universiti Selangor (UNISEL)

Zuraini Alias, Universiti Selangor (UNISEL)

Noor Ullah Khan, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (UMK)

Hanieh Alipour Bazkiaei, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (UMK)

Keywords

Investment Decision Behavior, Brand Familiarity, Perceived Trust, Attitude

Abstract

Over the years, the extant literature has investigated the influence of behavioral factors on investor decision-making. This study aims to further the research on behavioral aspects and investigate the effect of brand familiarity on investor’s investment decision in stocks. Specifically, the study tests the mediating role of perceived trust and attitude between brand familiarity and investment decision of retail investors in the Malaysian stock exchange. Structural equation modeling was used to test the proposed hypothesis by using the data of 247 retail stock investors. The study results indicate that perceived trust and attitude mediate the relationship between brand familiarity and investment decision. The direct relationship between brand familiarity and investment decision is not established. The result provides new theoretical insight and implications for the management as trust and a positive attitude can be created by enhancing brand familiarity, which influences stock investment decision.

Introduction

Financial markets can be better understood within the neoclassical theory of finance paradigm by utilizing models with fully rational representative agents. Investors make decisions in order to optimise their utility function while taking into account the applicable restrictions and preferences (Simon, 1959). According to “neoclassical finance theory, " individuals are fully aware of the marketplace and may rationally shape their actions when new information becomes available (Becker, 1962). As a result, the paradigm of conventional finance theory is built on two pillars: first, when new information arrives, agents update themselves according to Bayesian law. Second, the market's representative agents make decisions in line with the idea of anticipated utility, making it harder for those seeking anomalous gains to profit Efficient Market Hypotheses (Neumann & Morgenstern, 1944). However, real-world market behavior cannot always be described within the framework of conventional finance. Anomalies can be found in the market.

Long-standing oddities in traditional finance, such as individual trading behavior, average cross-sectional returns, the aggregate stock market, and the dividend problem, have altered the thinking dimension of financial scholars to a large extent. This change is from traditional finance theory based on rationality to behavioral finance theory based on normalcy. People defy the assumptions of conventional utility theory, according to recent tests and studies. When making risky decisions, the advent of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) has challenged the anticipated utility hypothesis. Individuals frequently stray from expected utility theory's assumptions and exhibit consistent behavior in prospect theory. Individuals do not always behave in line with the anticipated utility hypothesis, according to Shapira & Venezia (2001).

Many problems and anomalies in traditional finance, according to behavioral economists, can only be explained using the behavioral theory of finance. Behavioral economists (Thaler, 1990, 1999; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) challenge the conventional wisdom that man is economically reasonable. Behavioral theorists' extensive research on bounded rationality, biases, mental frames, judgment heuristics, and prospect theory cast doubt on conventional finance's rationality assumption, laying a new basis for finance based on human psychological behavior. The stock market is one of the investment platforms for both institutional and individual investors. According to Choong, Baharumshah, Yusop & Habibullah (2010), the stock market allows investors to trade and construct their portfolios. For institutional investors, trading in the stock market will enable them to enjoy easy access to capital through equity issues.

Furthermore, investing in the stock market allows individuals to accumulate wealth at a reasonable rate. (Mamun, Hasmat Ali, Hoque, Mowla & Basher, 2018), offers impressive returns, diversification benefits, and provides a safe place for long-term investment (O'Hagan? Luff & Berrill, 2019). Investment in the stock market benefits the institutional investors along with retail investors and the economy of a country. According to Mustafa, Ramlee & Kassim (2017). The stock market is commonly used to gauge a country's macroeconomic performance. An active and efficient stock market is generally related to well-developed financial systems and a growing economy (Choong et al., 2010).

Bursa Malaysia (previously known as the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange) was founded in 1976 and became publicly traded in 2005. Bursa Malaysia is one of ASEAN's most important stock exchanges, where investors may buy and sell stocks. As of December 31, 2018, 915 publicly traded firms indexed in Bursa Malaysia's three primary markets: Main Market, ACE Market, and LEAP Market (Malaysia, 2018b). Although the lucrative investment stock market may offer, some people, especially millennials, no longer are interested in buying and selling a share in the market (Roberge, 2019). According to Martin (2018), investors do not see the stock market as a path to build their wealth. Thus, they prefer to channel their funds to other alternatives such as property, bonds, and fixed deposits investment. To further enrich the stock market and attract more investors shortly, it’s critical to pinpoint the behavioral elements that impact an investor's willingness to put money into the stock market. According to recent research, variables such as financial literacy influence household involvement in the stock market. (Balloch, Nicolae & Philip, 2015), perception towards the brand (Frieder & Subrahmanyam, 2004), herding behavior (Kengatharan & Kengatharan, 2014), and trust (Georgarakos & Pasini, 2011; Pevzner, Xie & Xin, 2015).

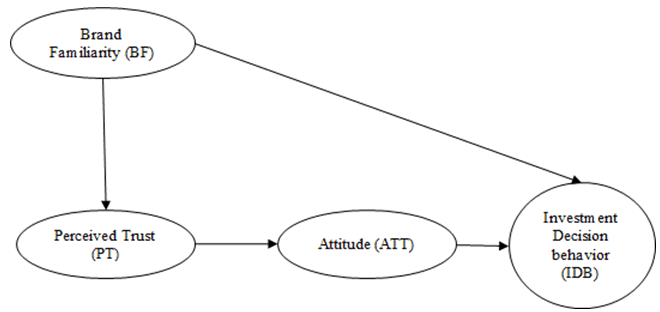

The notion of “brand familiarity” has been examined in a variety of marketing disciplines, including customer behavior (Bravo et al., 2012; Diallo et al., 2013), Effects of communication messages (Delgado?Ballester et al., 2012), and the aim to buy (Diamantopoulos et al., 2011; Nepomuceno et al., 2014). Recent marketing academics have repeatedly highlighted the importance of brand familiarity (Aspara & Takkanen, 2010). In addition, the links between people's subjective assessments of a company's goods and brands and their stock investing decisions have piqued attention (Aspara, 2011). Investors have been found to prefer investing in firms that they are familiar with in the financial environment (Aspara & Tikkanen, 2008). However, the extant literature so far does not provide a detailed theoretical examination of brand evaluation regarding the investment decision. Since a result, recognizing the company's brand is critical, as it reveals the stock's kind, market, and other unique features. When an investor has a high level of familiarity with a brand, they are more likely to trust it. A higher amount of “trust” can lead to a “positive attitude,” which manifests in investors' tend to behave and act positively according to the “Theory of Planned Behavior” (Ajzen, 1991). Therefore, to address the literature gap and anomalies in the stock market, a conceptual framework is developed to examine whether brand familiarity directly influences investment decision or a mediating mechanism that affects an investor’s trust, which translates into a positive attitude leading to investment decision in stocks.

Research Model and Theoretical Foundation

This paper developed a research model based on existing literature. The conceptual framework is shown in Figure 1. This study consisted of four constructs (i) brand familiarity as exogenous, (ii) perceived trust and (iii) attitude as mediator endogenous, and (iv) investment decision behavior as an endogenous variable. This study used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as an underpinning theory by justifying the relationships among the variables in the model (Ajzen, 1991).

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

This literature section discussed study variables. This section formulates a total of six hypotheses and literature key variables include (i) brand familiarity as exogenous, (ii) perceived trust, and (iii) attitude and (iv) investment decision behavior. Each relationship is discussed in the following section.

The Influence of Brand Familiarity on Perceived Trust and Investment Decision Behavior

According to Maurya & Mishra (2012), the definition of a brand can be differentiated from two perspectives; a consumer and a firm. From consumer perspective, a brand is an image in the consumer's mind, differentiated in terms of color, design, logo, and other distinctive features. From a firm’s perspective, a brand is a legal instrument that portrays the right image of a firm to its consumer (Maurya & Mishra, 2012).

On the other hand, brand familiarity is known as the awareness consumers have of a particular brand. “It is a direct result of the market segmentation and product differentiation strategy” (Maurya & Mishra, 2012). According to Delgado?Ballester, Navarro & Sicilia (2012), one of the most distinguishing characteristics of brands is "brand familiarity." The impact of brand-related elements on customer trust and judgment is extensively documented in marketing literature. A recent study on “brand familiarity” shows that exposure to a brand on a regular basis can increase consumer positivity towards the brand and enhance the consumer perceived trust (Benedicktus, Brady, Darke & Voorhees, 2010). According to Gray, Haefner & Rosenbloom (2012), as the consumers learn to trust the brand; they learn which brands meet their requirements and which ones do not. Regarding this paper, it is postulated that the higher familiarity of an investor towards a brand, the higher their perceived trust towards a particular Firm’s stock. Previous research has also demonstrated that recognizable brands have a favorable impact on “purchase intention” and “brand trust” (Porral, Fernández, Boga & Mangín, 2013; Semeijn, Van Riel & Ambrosini, 2004; Macdonald & Sharp, 2000) However, when it comes to influencer marketing, research on "brand familiarity" is equivocal. Hence, it was hypothesized:

H1: Brand familiarity has a significant positive relationship with the perceived trust

H2: Brand familiarity has a significant positive relationship with the investment decision

The Influence of Perceived Trust on Attitude

The term "trust" refers to a person's ability to put their trust in another person. “Beliefs regarding the likelihood that another’s future actions will be favorable, or at least not detrimental, to one’s interests” (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). For a firm, “trust” from investors is necessary to establish its reputation. In this paper, trust is conceptualized as the investor’s beliefs in managing the company and its stock performance. According to Georgarakos & Pasini (2011); Ng, Ibrahim & Mirakhor (2016); Pevzner, Xie & Xin (2015); Tucker, Yeow & Viki (2013), trust contributes significantly to stockholding and can be developed over time

In making economic decisions, including in-stock investment, “trust” serves as a replacement (Pevzner et al., 2015). Furthermore, in inferior information situations, trust plays a role. Georgarakos & Pasini (2011) assessed that trust impacts stock ownership through many pathways, with distrust lowering the expected return on investment, making stock market participation unappealing. A study was done by Tu & Bulte (2010) in China found a significant role of trust in rural China market participation. In addition, Ng, et al., (2016) found that trust plays a significant role, especially in countries with the weak rule of law, “non-Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (non-OECD)” and “Organization of Islamic Co- operation (OIC)” countries that are commonly categorized by lower formal institutional value. However, an individual’s degree of faith in the stock market isn't always linked to their understanding of the stock market. In other words, knowing about the market does not make the market trustworthy (Balloch et al., 2015). The direct and mediating effect of trust on attitude has been found in many studies (Barriere, 2016; McCole, Ramsey & Williams, 2010; Mohammad, Yusoff, Islam & Abdullah, 2014; Taniguchi, 2014). For example, Barriere (2016) examined the influence of trust on the attitude of employees towards human resource analytics in an organization. He found that trust in the organization (as an entity) plays a central role in determining the employees' attitudes. Based on the above, the following hypothesis was set forth:

H3: Perceived trust has a significant positive relationship to attitude

H4: Perceived trust mediates the relationship between brand familiarity and attitude

The Influence of Attitude on Investment Decision Behavior

The amount to which an individual has a favorable or unfavorable judgment or appraisal of the conduct in issue is characterized as an attitude (Ajzen, 1991). When people feel that certain activities lead to good results, they acquire positive attitudes toward such behaviors. In the context of this paper, when investors believe that the decision to invest in a stock is associated with desirable outcomes, their attitude towards investment will be developed.

According to Masini & Menichetti (2013), other than non-financial factors, investors investment decision is influenced by their social, political, and economic environment, which also includes investors’ readiness and favourableness to invest, as well as investors’ knowledge towards investment. Several studies have investigated the role of attitude in influencing investor’s investment decision (Cuong & Jian, 2014; Elliott, Bull & Mallaburn, 2015; Kaur & Kaushik, 2016; Masini & Menichetti, 2012). For example, Masini & Menichetti (2012) examined investor’s attitude in renewable energy type of investments, Elliott, Bull & Mallaburn (2015) explored the United Kingdom’s property investor attitudes towards low carbon Investment decisions in commercial buildings, while Kaur & Kaushik (2016) studied the influence of attitude as one of the determinants of investment behavior of investors in India.

In addition, this paper further investigates the roles of attitude in mediating the relationships between perceived trust and investment decision. The mediating effect of attitude has been found in many studies and in a different context, such as an intention to purchase a product (Chu, 2018) and towards a particular behavior (Akhtar & Soetjipto, 2014; Hassan, Masron, Noor & Ramayah, 2018). Hence, it was hypothesized:

H5: Attitude has a significant positive relationship to investment decision

H6: Attitude mediates the relationship between perceived trust and investment decision

Research Methodology

The questionnaire was divided into two sections. Section A consists of twenty-seven questions measuring four variables used in the paper. The variable’s measurement items were derived from existing literature. Scales for the investor’s decision making (eight items) were adapted from (Khan, 2014), while attitude (six items), perceived trust (five items), and brand familiarity (eight items) were adapted from Ali (2011). The items were measured using a five- point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Section B; on the other hand, consist of demographic questions related to respondent’s characteristics. The sample of this paper consists of 247 retail investors who have invested in “Bursa Malaysia (Formerly known as Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange)”.

Bursa Malaysia was recognized as one of the top exchanges in ASEAN with a diversified investor base for its exceptional performance (Bursa Malaysia, 2018a). The sample size was determined using “inverse square root” and “gamma-exponential methods” (Kock & Hadaya, 2018). The minimal sampling size is 237, calculated using WarpPLS 6.0 with a minimum significant path model coefficient of 0.107, a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.50. As a result, this article received 247 surveys, which is more than the required sample size. Due to the non-availability of the sample frame, data was obtained using a structured questionnaire employing a non-probability, judgmental sampling approach.

Data Analysis and Results

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) is used for the data analysis. PLS-SEM is a causal predictive method used when the study's objective is to explain the variance in the target construct and prediction (Wold, 1982; Sarstedt et al., 2017a). Using SmartPLS 3.3.3 (Ringle, Wende & Becker, 2015), the measurement and structural model assessment were performed. After measurement model assessment, the structural model is assessed.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

The results from demographic data depict that the majority (189) of the respondents were males, representing about 76.5% of the total sample. Thus, 58 respondents were female, representing 23.5%. 66.4 percent of respondents were between the ages of 30-34, 12.6 percent were between the ages of 35-39, 11.3 percent were between the ages of 40-44, and the remaining 6.9% and 2.8 percent were between the ages of 25-29 and above 45 years of age, respectively. In addition to that, most respondents (58.3%) worked in the private sector, followed by 21.9 percent who were self-employed, 10.5 percent who worked in the public sector, and the remaining 9.3 percent who listed their employment as "other." In terms of marital status, 78.5 percent of respondents said they were married, 11.7 percent said they were divorced, and 9.7 percent said they were still single. Furthermore, the bulk of responders (83%) have a bachelor's degree, 8.5 percent have a master's degree, 6.5 percent have an A-level diploma, and around 2% have a PhD.

Common Method Variance

Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee & Podsakoff (2003) mentioned that there is observable covariance because the variables were collected from a single source. As a result, this research used numerous design-related procedural steps proposed by (Podsakoff et al., 2003) to decrease the risk of common method variance. First, it was ensured that the data collected is psychologically separated by clearing to the participants that the measurement of independent and dependent variables are not related. Secondly, the structure of the items was simple, concise, and no double-barrel question was used. Harman's single factor statistical approach is used as a statistical check to see if common method variance exists. Table 1 shows the results of Harman’s single-factor analysis.

| Table 1 Common Method Variance |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sum of Square Loadings | |||||

| % of Cumulative | % of Cumulative | |||||

| Component | Total | Variance | % | Total | Variance | % |

| 1 | 7.959 | 29.479 | 29.479 | 7.586 | 29.096 | 28.096 |

| 2 | 4.966 | 18.392 | 47.871 | 4.569 | 16.923 | 45.020 |

| 3 | 2.377 | 8.656 | 56.527 | 1.937 | 7.714 | 52.193 |

| 4 | 1.888 | 6.991 | 63.518 | 1.504 | 5.571 | 57.764 |

| 5 | 1.209 | 4.477 | 97.996 | 0.833 | 3.087 | 60.851 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring | ||||||

Assessment of Measurement Model Convergent Validity

The measurement analysis is the initial stage in PLS-SEM. The measurement model was assessed based on three criteria’s (i) Average Variance Extracted (AVE), (ii) Composite Reliability (CR) and (iii) factor loading. Consistent with the suggestions of Nunnally (1978) and Gefen, Straub, & Boudreau (2000), all of the items' composite dependability and rho value exceeded the standard value of 0.708. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs is likewise all items loading was above 0.50 suggested by Fornell & Larcker (1981) as the cutoff value of 0.50. The scales for measuring these constructs were judged to have adequate convergence reliability if all three reliability values were above the recommended threshold levels by Bagozzi & Yi (1988) see Table 2.

| Table 2 Reliability and Validity Test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) | rho | |

| Investment DecisionBehaviour | 0.679 | 0.944 | 0.936 |

| Attitude | 0.627 | 0.909 | 0.891 |

| Perceived Trust | 0.648 | 0.902 | 0.648 |

| Brand Familiarity | 0.570 | 0.914 | 0.885 |

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity tests were used to determine the construct validity (Hair, Gabriel & Patel, 2014). The discriminant validity test was evaluated using the Fornell and Larcker criterion and the “Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT)” ratio of correlations (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2015). According to the results, the square root of AVE is larger than the correlations across components. All constructs have an HTMT value of less than 0.90, implying that the measuring model has strong discriminant validity see Table 3 and 4.

| Table 3 Fornell and Lacker Criterion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | BF | IDB | PT | |

| ATT | 0.792 | |||

| BF | 0.147 | 0.755 | ||

| IDB | 0.578 | 0.177 | 0.824 | |

| PT | 0.191 | 0.448 | 0.135 | 0.805 |

| Table 4 HTMT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | BF | IDB | PT | |

| ATT | ||||

| BF | 0.181 | |||

| IDB | 0.625 | 0.190 | ||

| PT | 0.220 | 0.484 | 0.151 | |

Assessment of the Structural Model

Coefficients of variables (β), t-values, multivariate coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), predictive relevance (Q2), and PLS predict are all examples of structural model assessment.

Collinearity Statistics

To quantify the severity of multicollinearity for variables, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test was performed. Table 5 presents the collinearity results, which revealed that the VIF values for the variables were acceptable, ranging from 1.814 to 3.718, indicating that multicollinearity is not a critical problem in this paper.

| Table 5 Collinearity Statistics |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | ATT1 | 3.718 | PT | PT1 | 2.331 |

| ATT2 | 3.545 | PT2 | 2.780 | ||

| ATT3 | 1.984 | PT3 | 2.222 | ||

| ATT4 | 1.814 | PT4 | 1.823 | ||

| ATT5 | 2.459 | PT5 | 2.154 | ||

| ATT6 | 2.150 | - | - | ||

| BF | BF1 | 2.939 | IDB | IDB1 | 3.230 |

| BF2 | 2.416 | IDB2 | 3.619 | ||

| BF3 | 2.179 | IDB3 | 2.901 | ||

| BF4 | 1.855 | IDB4 | 2.813 | ||

| BF5 | 2.478 | IDB5 | 2.218 | ||

| BF6 | 2.181 | IDB6 | 2.610 | ||

| BF7 | 2.356 | IDB7 | 3.494 | ||

| BF8 | 2.650 | IDB8 | 2.858 | ||

Testing the Significance of the Path Model

Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was used to assess the relevance of the route model, as advised by (Hair et al., 2014). The direct paths are represented with hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, and H5), while mediation paths are represented with hypotheses (H4 and H6). Table 6 present the summary of the results based on the structural model using the SmartPLS-SEM.

| Table 6 Path Coefficient |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Beta | T value | P value | Decision |

| H1 | BF à PT | 0.448 | 8.751 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | BF à IDB | 0.093 | 1.581 | 0.600 | Not Supported |

| H3 | PT à ATT | 0.191 | 3.179 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H4 | ATT à PT à IDB | 0.110 | 3.002 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H5 | ATT à IDB | 0.578 | 12.323 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | BF à PT à ATT | 0.049 | 2.656 | 0.007 | Supported |

R-square, Effect Size, and Predictive Relevance

R-square values were performed to measure the strength of the correlation of the relationship, whereby a small value means that the relationship explains a small amount of the variance in the data. In this paper, brand familiarity can explain 20.1 percent of the variations of perceived trust. In addition, perceived trust can explain 3.6 percent of the variations of attitude, while attitude is able to explain 33.4 percent of the variations of investment decision behavior. This paper also measures the effect size (f2) of the variable. According to Cohen (1992), a value from 0.02 to 0.14 is considered weak, 0.15 to 0.34 is moderate, and 0.35 and above is a strong effect. Based on the analysis, the Q2 values for brand familiarity are 0.116, while Q2 values for perceived trust and attitude are 0.020 and 0.208, respectively. The structural model results are summarized in Table 7.

| Table 7 R-Square, Effect Size and Predictive Relevance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | R-square (R2) | Effect size (f2) | Predictive relevance (Q2) |

| BF à PT | 0.201 | 0.251 | 0.116 |

| PT à ATT | 0.036 | 0.038 | 0.020 |

| ATT à IDB | 0.334 | 0.051 | 0.208 |

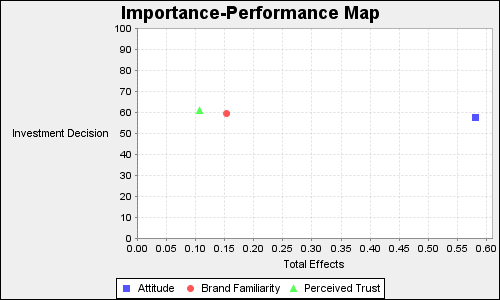

Important Performance Map Analysis

The Important Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) incorporates the average values of the latent scores into the PLS-SEM findings (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). IPMA analysis aids in determining the relevance of a construct in forecasting the performance of a target construct. Three conditions must be met to conduct out IPMA: first, the indicator scales utilized must be equidistance. Second, the coding for all indicators must be in the same direction. A bad consequence must be represented by a low value on the scale, while a high number must represent a positive outcome. Finally, estimations for outer weights must be positive. The components in this study are measured using a Likert scale with a neutral scale that is equidistance in nature. Second, the Likert scale runs from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement, which meets the IPMA requirements. Finally, the model's projected outer weights are positive. Hence IPMA analysis can be carried out for the present model as the model has satisfied three preconditions of IPMA. For the present study, the investment decision is the target construct. The IPMA analysis showed that all the three constructs are performing equally. However, attitude is essential for investment decision which is followed by brand familiarity and perceived trust. From a management aspect, all the three variables are performing similarly; hence should be given importance see Table 8 and Figure 2.

| Table 8 Important Performance Map Analysis |

||

|---|---|---|

| Criterion: IDB | Total Effect | Performance |

| ATT | 0.581 | 57.421 |

| BF | 0.153 | 59.408 |

| PT | 0.107 | 61.022 |

This paper develops six hypotheses. First, this paper examines the significant relationship between brand familiarities on perceived trust. Second, it was examined that whether there is a direct relationship between brand familiarity and investment decision. Third, the influence of perceived trust on investor attitude was investigated. The perceived trust also has been hypothesized to mediate the relationship between brand familiarity and attitude. Next, the attitude was hypothesized to have a significant relationship with investment decision, and lastly, the attitude was hypothesized to mediates the relationship between perceived trust and investment decisions.

The results of this paper support all the proposed hypotheses, except the direct relationship between brand familiarity and investment decision is not supported. In brief, brand familiarity has a significant relationship to perceived trust however; there is no direct relationship between brand familiarity and investment decision. Brand Perceived trust has a significant relationship with attitude, and attitude has a significant relationship to the decision to invest. The mediation analysis also generates a significant relationship, whereby perceived trust has been found to mediate the relationship between brand familiarity and attitude. In contrast, attitude mediates the relationship between perceived trust and investment decisions. The relationship between brand familiarity and perceived trust had the broadest effects (f2=0.251) and generated a significant result. The results suggest that investors are likely to trust the company when they are familiar with its brand. Implicitly, brand managers should focus on consistent brand messages to build investors' trust towards the company. Perceived trust was found to have a significant relationship with attitude, suggesting that trust can influence investors' favorable evaluation of the decision to invest. The result is consistent with the finding documented by Barriere (2016), who examined the influence of trust on employees' attitudes. This paper also found that the positive effect of attitude on investment decision, suggesting that favorable evaluations on investing play an essential role in influencing an individual’s decision to invest in the stock market.

The result of this study showed that trust mediates the relationship between brand familiarity and attitude. Generally, the results suggest that if the investor is familiar with the company’s brand and trusts the company, those investors will develop a positive attitude to invest in the company’s stock. This supports the notion that trust affects stock market participation (Ng et al., 2016). This paper also found the role of attitude in mediating the relationship between perceived trust and investment decisions. The result implies that if the investor trusts the company and has a favorable evaluation towards investing in the company’s stock, then those investors will invest in the company.

Conclusion

This research contributes to consumer behavior and behavioral finance literature and has implications for managerial practice and policymaking. This study's results help the company better understand factors that influence investors to decide to invest in the stock market. This paper also hopes to shed some light on companies trying very hard to attract investors to invest in their company stock. They need to recognize the factors so that they can take the necessary steps to attract potential investors. The results of this paper should also enlighten brand managers in planning their marketing strategies. In addition, public listed companies will be more knowledgeable in their investors' behavior and preference towards stock investment. Thus, they may take the necessary actions to influence investor’s preferences towards their company stock. Future research may explore the following topics. First, as a stock market investment decision is multifaceted, future research may delve into the determinants of other underlying aspects such as economic, social, or environmental. These aspects are relevant given the importance of other external factors that may influence an investor's investment decision. Second, since the stock market is no longer attractive to young ones and millennials as an alternative investment instrument, it might be worthwhile to examine the factors behind this situation. Word of mount and initiatives might have a role to play. As the decision to invest is determined by brand familiarity, trust, and attitude, future research should focus primarily on how these determinants could be further developed and enhanced. As such, the stock market is still relevant as one of the investment platforms.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

- Akhtar, H., & Soetjipto, H.P. (2014). The role of attitude to mediate the effect of knowledge on people’s waste minimization behaviour in Terban, Yogyakarta. Journal of Humans and the Environment, 21(3), 386–392.

- Ali, A. (2011). Predicting individual investors’ intention to invest: An experimental analysis of attitude as a mediator. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 6(1), 57–73.

- Aspara, J., & Tikkanen, H. (2008). Interactions of individuals' company-related attitudes and their buying of the companies' stocks and products. Journal of Behavioural Finance, 9 (2), 85-94.

- Aspara, J. (2011). The influence of product design evaluations on investors’ willingness to invest. Design Management Journal, 6, 79–93.

- Aspara, J., Hietanen, J., & Tikkanen, H. (2010). Business model innovation vs replication: Financial performance implications of strategic emphases. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18 (1), 39-56.

- Bagozzi, R.P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Balloch, A., Nicolae, A., & Philip, D. (2015). Stock Market literacy, trust, and participation. Review of finance, 19(5), 1925–1963. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfu040

- Barriere, J.M. (2016). The influence of trust on attitude of employees towards HR Analytics in organisations, 1–9.

- Retrieved from http://essay.utwente.nl/70805/

- Becker, G.S. (1962). Irrational behavior and economic theory. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(1), 1–13.

- Benedicktus, R.L., Brady, M.K., Darke, P.R., & Voorhees, C.M. (2010). Conveying trustworthiness to online consumers: Reactions to consensus, physical store presence, brand familiarity, and generalized suspicion. Journal of Retailing, 86(4), 322–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2010.04.002.

- Bravo, R., Montaner, T., & Pina, J.M. (2012). Corporate brand image of ?nancial institutions: A consumer approach. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21. 232–245.

- Bursa Malaysia. (2018a). Creating opportunities, growing value: Governance and Financial Reports 2018.

- Bursa Malaysia. (2018b). Creating opportunities, growing value: Integrated annual report 2018. Retrieved from http://bursa.listedcompany.com/misc/Integrated_Annual_Report_2018.pdf.

- Choong, C.K., Baharumshah, A.Z., Yusop, Z., & Habibullah, M.S. (2010). Private capital flows, stock market and economic growth in developed and developing countries: A comparative analysis. Japan and the World Economy, 22(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2009.07.001.

- Chu, K.M. (2018). Mediating influences of attitude on internal and external factors influencing consumers’ intention to purchase organic foods in China. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(12), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124690.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1038/141613a0. Cuong, P.K., & Jian, Z. (2014). Factors influencing individual investors’ behavior: An empirical study of the

- Vietnamese stock market. American Journal of Business and Management, 3(2), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.11634/216796061403527.

- Delgado?Ballester, E., Navarro, A., & Sicilia, M. (2012). Revitalising brands through communication messages: The role of brand familiarity. European Journal of Marketing, 46(1/2), 31–51.

- Diallo, M.F., Chandon, J.L., Cliquet, G., & Philippe, J. (2013). Factors in?uencing consumer behavior towards store brands: Evidence from the French market. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 41, 422–441. DOI:10.1108/09590551311330816.

- Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B., & Palihawadana, D. (2011). The relationship between country-of-origin image and brand image as drivers of purchase intentions: A test of alternative perspectives. International Marketing Review, 28, 508–524. DOI:10.1108/02651331111167624.

- Elliott, B., Bull, R., & Mallaburn, P. (2015). A new lease of life? Investigating UK property investor attitudes to low carbon investment decisions in commercial buildings. Energy Efficiency, 8(4), 667–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-014-9314-2

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Frieder, L., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2004). Brand perceptions and the market for common stock. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 40(1), 57–85.

- Frieder, L., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2005). Brand perceptions and the market for common stock. Journal of financial and Quantitative Analysis, 40 (1), 57-85.

- Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M.C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the association for information systems, 4. https://doi.org/10.17705/1cais.00407

- Georgarakos, D., & Pasini, G. (2011). Trust, sociability, and stock market participation. Review of Finance, 15(4), 693–725. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfr028

- Gray, Z.D., Haefner, J.E., & Rosenbloom, A. (2012). The role of global brand familiarity, trust and liking in predicting global brand purchase intent: A Hungarianâ American comparison. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 4(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbem.2012.044316.

- Hair, J.F., Gabriel, M.L.D., da, S., & Patel, V.K. (2014). AMOS Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Marketing Magazine, 13(02), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.5585/remark.v13i2.2718.

- Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C.M. (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares.

- European Journal of Marketing forthcoming.

- Hassan, S.H., Masron, T.A., Noor, M., & Ramayah, T. (2018). Antecedents of trust towards the attitude of charitable organisation in monetary philanthropic donation among generation-Y. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 23(1), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.21315/aamj2018.23.1.3

- Helm, S. (2007). The role of corporate reputation in determining, investor satisfaction and loyalty. Corporate Reputation Review, 10 (1), 22-37.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance- based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Kaur, I., & Kaushik, K.P. (2016). Determinants of investment behaviour of investors towards mutual funds. Journal of Indian Business Research, 8(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-04-2015-0051

- Kengatharan, L., & Kengatharan, N. (2014). The influence of behavioral factors in making investment decisions and performance: Study on investors of colombo stock exchange, Sri Lanka. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, 6(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5296/ajfa.v6i1.4893

- Khan, M.H. (2014). An empirical investigation on behavioral determinants of perceived investment performance; Evidence from Karachi stock exchange. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 5(21), 2222–2847.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263−291.

- Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12131

- Mamun, A., Hasmat Ali, M., Hoque, N., Mowla, M.M., & Basher, S. (2018). The causality between stock market development and economic growth: Econometric evidence from Bangladesh. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 10(5), 212. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v10n5p212

- Macdonald, E.K., & Sharp, B.M. (2000). Brand awareness effects on consumer decision making for a common, repeat purchase product: A replication. Journal of Business Research, 48(1), 5–15.

- Martin, E. (2018). Only 23% of millennials prefer investing to cash—here’s why they’re skeptical of the stock market. CNBC.

- Masini, A., & Menichetti, E. (2012). The impact of behavioral factors in the renewable energy investment decision making process: Conceptual framework and empirical findings. Energy Policy, 40(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.06.062

- Maurya, U.K., & Mishra, P. (2012). What is a brand?: A perspective on brand meaning. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(3), 122-133–133.

- McCole, P., Ramsey, E., & Williams, J. (2010). Trust considerations on attitudes towards online purchasing: The moderating effect of privacy and security concerns. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 1018–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.02.025

- Mohammad, A.N., Yusoff, R.Z., Islam, R., & Abdullah, A. (2014). Effects of consumers’ trust and attitude toward online shopping. American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 6(2), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajebasp.2014.58.71

- Morrison, E.W., & Robinson, S.L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops Academy of Management Review, 22, 226–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180265

- Mustafa, S.A., Ramlee, R., & Kassim, S. (2017). Economic forces and Islamic stock market: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting, 10(1), 45–85.

- Neumann, V.J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior (2nd Edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ng, A., Ibrahim, M.H., & Mirakhor, A. (2016). Does trust contribute to stock market development? Economic Modelling, 52, 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.10.056

- Nepomuceno, M.V., Laroche, M., & Richard, M.O. (2014). How to reduce perceived risk when buying online: The interactions between intangibility, product knowledge, brand familiarity, privacy and security concerns. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21,619–629. DOI:10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.11.006.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd edition). New York, Oliver: McGraw-Hill.

- O'Hagan-Luff, M., & Berrill, J. (2019). The international diversification benefits of US?traded equity products.

- International Journal of Finance & Economics, 24(3), 1238-1253.

- Pevzner, M., Xie, F., & Xin, X. (2015). When firms talk, do investors listen? The role of trust in stock market reactions to corporate earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 190–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.08.004.

- Porral, C.C., Fernández V.A.M., Boga, O.J., & Mangín, J.P.L. (2015). Measuring the influence of customer-based store brand equity in the purchase intention. Management Notebooks, 15(1), 93-118.

- Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., & Podsakoff, N.P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Ringle, C.M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt. Retrieved from http://www.smartpls.com.

- Roberge, E. (2019). Millennials need to get off the sidelines and start investing now. CNBC.

- Schoenbachler, D.D., Gordon, G., Aurand, L., & Timothy, W. (2004). Building brand loyalty through individual stock ownership. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 13(7), 488-497.

- Semeijn, J., Van Riel, A., & Ambrosini, A. (2004). Consumer evaluation of store brands: Effects of store image and product attributes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 11(4), 247-258.

- Shmueli, G., Ray, S., Velasquez Estrada, J.M., & Chatla, S.B. (2016). The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. Journal of Business Research, 69, 4552–4564

- Simon, H.A. (1959). Theories of decision-making in economics and behavioral science. American Economic Review, 49(3), 253–283.

- Taniguchi, Y. (2014). The level of trust and the consumer attitude toward organic vegetables: Comparison between Japanese and German Consumers. In building organic bridges, 13–15.

- Thaler, R.H. (1990). Anomalies: Saving, fungibility, and mental accounts. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(1), 193–205.

- Tu, Q., & Bulte, E. (2010).Trust, market participation and economic outcomes: Evidence from Rural China. World Development, 38(8), 1179–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.12.014

- Tucker, D.A., Yeow, P., & Viki, G.T. (2013). Communicating during organizational change using social accounts: The importance of ideological accounts. Management Communication Quarterly, 27(2), 184–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318912469771

- Wold HOA. (1982). Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. In: Jöreskog KG and Wold HOA (Editions) Systems Under Indirect Observations: Part II. Amsterdam: NorthHolland, 1-54.