Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6

Does Organizational Commitment and Psychological Empowerment Explain the Relationship Between P-J Fit and OCB?

S. Martono, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Moh. Khoiruddin, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Nury Ariani Wulansari, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Vini Wiratno Putri, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Siti Ridloah, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Citation: Martono, S., Khoiruddin, M., Wulansari, N.A., Putri, V.W., & Ridloah, S.(2021). Does organizational commitment and psychological empowerment explain the relationship between p-j fit and OCB?. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 20(6), 1-12.

Abstract

The objective is to explain the effect of Person-Job Fit on OCB through organizational commitment as the mediating variable and psychological empowerment as the moderating variable. The samples of this study are 125 educational staff at state university in Indonesia as the respondents. The results of the study show that P-J Fit increases organizational commitment, organizational commitment also improves OCB and mediates the relationship of person job-fit and OCB. On the other hand, psychological empowerment does not moderate the effect of organizational commitment on OCB. This study is to answer the needs of the previous research by studying the mediating and moderating mechanisms in different organizations and countries. It provides an understanding that psychological empowerment may give more roles as a mediating or antecedent than as a moderating variable. Then, psychological empowerment is an important component to be understood.

Keywords

Person-Job Fit, OCB, Organizational Commitment, Psychological Empowerment.

Introduction

The shift from a product-based economy to a knowledge-based economy has increased the organization’s need to have the right employees to fulfill business challenges. This condition makes the concept of person-environment fit (P-E fit) and its relationship with employee attitudes are continuously reviewed (Kim & Gatling, 2019; Straatmann et al., 2020). Individual compatibility and environment play an important role to determine his behavior in the organization and the jobs. The concept of person-environment fit (P-E fit) is defined as compatibility between an individual and his/ her work environment which happens if the characteristics are fit each other (Kristof-brown et al., 2005; Kristof, 1996). One of the important aspects of the concept of Person-Environment Fit (P-E fit) is Person-Job Fit (P-J Fit).

P-J Fit is the compatibility between employees and the job or tasks (Carless, 2005). The compatibility between employees and their job requirements leads to better outcomes. The previous studies also prove that organizational commitment can be driven by the compatibility between employees and their jobs. For example; Chhabra (2015) finds that the more employees feel compatible with their work, the higher their commitment to the organization. Therasa & Vijayabanu (2016) also find that one of the driving factors of organizational commitment is the compatibility between employees and their jobs.

The important role of P-J Fit is not limited to encourage employees to be more committed to their organization. Employee commitment ultimately encourages other positive work outcomes. One of the important consequences of employee commitment is Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB). Obedgiu et al. (2017) find that employees tend to engage with organizational citizenship behavior when they have a strong organizational commitment. It is in line with the study done by Paul et al. (2016) which prove that an important factor that encourages employees to OCB is the strong commitment to the organization. It means that P-J Fit has the potential to encourage organizational commitment which leads to a higher OCB. However, there were inconsistent study results on P-J Fit and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) through organizational commitment. Van Loon et al. (2017) find that P-J is not proven to be a factor driving on OCB. Meanwhile, other studies stated that P-J Fit is an important factor to encourage OCB (Farzaneh et al., 2014; Jawad et al., 2013). Thus; it needs research to clarify the P-J Fit on employee OCB. The previous researches have proven that P-J Fit is significant to influence organizational commitment (Chhabra, 2015; Therasa & Vijayabanu, 2016). On the other hand, Straatmann et al. (2020) stated that organizational commitment is more influenced by person-organizational fit than P-J Fit. This is because P-J Fit is not able to affect organizational commitment perfectly. It needs a study to re-examine the effect of P-J Fit on organizational commitment and OCB.

Organizational commitment has the potential to be the mediating variable between OCB and its antecedent factors. However, as a mediating variable, it needs to be re-explained. Farzaneh et al. (2014) has proven that organizational commitment can be the mediating variable between P-J Fit and OCB. On the other hand, Rayton et al. (2019) study person-environment fit (P-E fit) on work outcomes through organizational commitment as the mediating variable. The results show that organizational commitment is not suitable to be the mediating between P-J Fit and work outcomes.

Straatmann et al. (2020) advise testing the effect of a P-J Fit on the work outcomes by taking into account the moderating factor. The moderating factor of the study is psychological empowerment. Jha (2014) states that psychological empowerment plays a role in explaining OCB. Psychological empowerment is an important aspect that can help improving employee OCB. In this study; psychological empowerment is the moderating variable between organizational commitment and OCB. When an employee feels empowered, it is predicted that his organizational commitment can encourage extra-role behavior.

Furthermore; Kim & Gatling (2019) suggest studying the mechanism of P-J Fit on organizational citizenship behavior by considering organizational commitment in the different sample contexts. Previously, Islam et al. (2016) also suggest reviewing psychological empowerment, organizational commitments, and extra-role behaviors in different sectors. The suggestions for reviewing these mechanisms in different contexts are also mentioned in other literature (Astakhova, 2016; Buyukyilmaz, 2018; Farzaneh et al., 2014). Based on the various needs of the research, the study examines the effect of P-J Fit on OCB through organizational commitment as the mediating variable and psychological empowerment as the moderating variable in Indonesian State Universities. It is as suggested by Teimouri et al. (2015), to study OCB mechanisms in universities or higher education institutions.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

P-J Fit, Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational citizenship behavior is an individual behavior within the organization; it is defined as an extra role behavior rather than its formal roles and responsibilities (Organ, 1994). OCB occurs when an individual performs work behavior beyond his formal work descriptions by assisting his or her work social environment. This behavior is not formally and explicitly assessed by the existing award system (Paul et al., 2016). OCB includes social behaviors; such as caring about other people’s work, helping co-workers, and other voluntary behaviors that are beyond their responsibilities (?e?en et al., 2014).

Furthermore, organizational commitment reflects when employees have loyalty and identification with the organization and feel like they want to continue to be a part of the organization (Lambert et al., 2008). In short, organizational commitment is employee loyalty to employers. Organizational commitments are formed when employees and organizations foster great interest and desire to maintain their working relationships. Organizational commitment is the emotional connection that employees feel with their work (Obedgiu et al., 2017).

While P-J Fit is a concept derived from person-environment (P-E) fit. The concept of P-E fit reflects the conditions in which the individual feels he or she fits into his or her environment. P-J Fit describes the extent to which the demands of the job are tailored to the person's knowledge, skills, and abilities (Kristof-brown et al., 2005; Straatmann et al., 2020). PJ-fit can be seen from two perspectives; the fit between the knowledge, ability, and expertise of employees and the work requirements or the fit between the needs and preferences of employees and what is provided by the work (Ard?ç et al., 2016; Kristof-brown et al., 2005). When an employee makes a cognitive comparison between his needs and what the job provides (i.e. resources) and the skills he has are fit to the demands of the job, then his P-J Fit arises. The perception of this P-J Fit will determine how employees behave in their work and organization (Rayton et al., 2019).

Some literature has shown that conformity between P-J Fit is a driving factor on organizational commitment. It is stated by Chhabra (2015) that P-J Fit can encourage organizational commitment. P-J Fit is one of the important antecedents of employees’ organizational commitments (Soelton et al., 2020; Therasa & Vijayabanu, 2016). The relationship is defined as a self-identity theory (Tajfel, 1974). The theory provides an understanding that individuals use social categories to classify and define others and themselves. This social category can help the good order in the environment and help individuals to find their place in that environment (Tajfel, 1974). When employees feel they are fit for their work, they tend to feel owned and tied to the job. It plays an important role in engaging employees with higher commitments. The higher the P-J Fit between employees and their work, the higher their organizational commitment.

Committed employees tend to engage in behavior that supports the organization. A strong desire to be a part of the organization will encourage individuals to perform better (Paul et al., 2016). Social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) also supports the positive relationship between commitment and OCB. Based on the social exchange theory, job attitudes (e.g. commitments) increase due to the work environment in which job attitudes determine the employee's response to his organization (Lambert et al., 2008). Employees, who experience positive exchanges with organizations, will have a higher commitment and also contribute more by showing a high OCB. Srivastava & Dhar (2016) prove that organizational commitment can encourage employee extra-role behavior. Soelton et al. (2020) also find that employees who have higher commitments will show higher OCB. Organizational commitment is proven to be a factor that can directly improve employee OCB (Jin eta l., 2018; Khan et al., 2016; Khaola & Sebotsa, 2015; Paul et al., 2016). In addition to playing a direct role, organizational commitment can also be the mediating variable.

Farzaneh et al. (2014) demonstrate that OCB may be affected by P-J Fit through organizational commitment as the mediating variable. Paul et al. (2016) has proven that commitment plays an important role in facilitating the antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Previously, Chhabra (2015) also shows the important role of organizational commitment in facilitating P-J Fit on work outcome. Furthermore; Soelton et al. (2020) also find that P-J Fit and OCB are mediated by organizational commitment. Committed employees have loyalty and a high sense of assisting the organization. It is the key connecting P-J Fit and OCB. P-J Fit can encourage extra-role behavior and increase organizational commitment. Based on this explanation, it is hypothesized:

H1 P-J Fit gives a positive effect on organizational commitment

H2 Organizational commitment gives a positive effect on OCB

H3 Organizational commitment is to mediate P-J Fit and OCB

The Moderation Role of Psychological Empowerment

Empowerment is related to situations where individuals have the roles to shape and influence their organizational activities. Psychologically-empowered employees tend to feel delegated by their work environment. With empowerment, employees can take initiatives in decision making, and respond to job challenges innovatively (Jha, 2014). Employees feel empowered psychologically when they feel the autonomy to make decisions in getting the job done (Singh & Singh, 2019). This condition encourages employees to perform extra performance beyond their formal responsibilities.

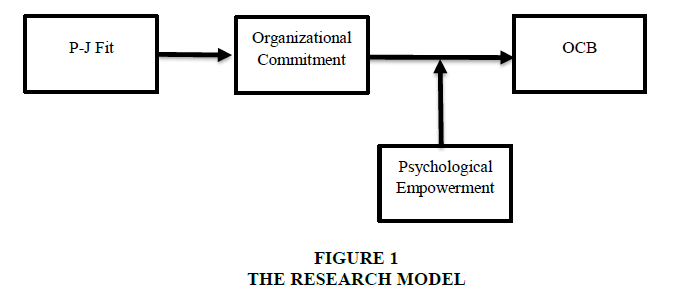

Empowerment plays an important role in improving effective performance. Singh & Singh (2019) prove that psychological empowerment provides an important role in encouraging employee’s OCB. Psychologically; empowered employees are considered more competent and productive in their work, and positively affect the effectiveness of the organization (Srivastava & Dhar, 2016). With psychological empowerment, employees tend to be involved to do works beyond their formal job descriptions (Islam et al., 2016). Previously, Macsinga et al. (2015) also prove that psychological empowerment is important for employees to encourage positive work outcomes. The results are also found by Newman et al. (2017) which show that the OCB mechanism is strongly influenced by the psychological empowerment factors employees have (Figure 1).

H4 Psychological empowerment moderates the effect of organizational commitment on OCB.

Employees who feel psychological empowerment tend to have higher capacity and self-efficacy and are willing to contribute to solving organizational problems beyond their responsibilities. This condition makes employees who have organizational commitment will show more organizational citizenship behavior. Farzaneh et al. (2014) find that psychological empowerment can strengthen the effect of organizational commitment on organizational citizenship behavior. The more employees feel psychological empowerment, the stronger the effect of organizational commitment on OCB. Based on this explanation, it is hypothesized:

Research Methods

The samples of the study are 125 educational staff of state university in Indonesia. Data are collected by distributing the questionnaires with a Likert scale of 1-5. The questionnaires are distributed online and offline. First, it is distributed online by Google form, and then it is distributed offline to get those respondents as required by the study. All 25 question items are declared valid and reliable. Hypotheses are then tested by using path coefficient value and performed with a t-test through SmartPLS 3.0.

Variable Measurement

The dependent variable of OCB is measured by using 10 question items from Podsakoff et al. (1997). Here are some examples of question items from OCB “I make time to help my co-workers’ difficulty”, “I am willing to share the knowledge with other colleagues”, “I took the initiative to be an advisor when my co-workers are in dispute”, “I have taken anticipation measures to prevent problems with other co-workers while working”, and “I discussed with colleagues and the leaders on things related to work”.

P-J Fit as the independent variable measured by 4 question items from (Cable & Derue, 2002). Here are some examples of P-J Fit question items “I feel I am fit to the works I do”, “The comparison between the demands of work and my abilities is appropriate”, and “My abilities and skills are perfect to do my job”.

Organizational commitment as the mediating variable is measured by 5 question items from Cook & Wall (1980). Here are some question items on organizational commitment “I am proud to tell people that I work in this organization”, “I feel myself is a part of this organization”, and “I am happy if my work can contribute to this organization”.

Psychological empowerment is the moderating variable measured by 6 question items from (Spreitzer, 1995). Here are some questions of psychological empowerment “The work I do is very important and meaningful to me”, “I am confident with my abilities in getting the job done”, and “I have authority in the work”.

Results

The background of the respondents is dominated by men (53%) and the ages are between 31- 40 years (35%). The most respondents’ employment status are civil servants (73%), the working period is for 11-20 years (46%) and S1 (Bachelor degree) as the educational background (48%). Mean, standard deviation, and correlation to each variable can be seen in Table 1. The correlation among organizational commitment and other variables ranges from 0.640 to 0.733 (all ρ< 0.01). The correlation between OCB and other variables ranges from 0.750 to 0.586. The value for organizational commitment (M=22.43) and OCB with the highest value scale (M= 42.90). Other variables such as; P-J Fit has a value (M=16.42) and psychological empowerment has a value (M=23.98). It means that the test model of structural equations can be used.

| Table 1: Mean, Standard Deviation, And Correlation Among Variables | ||||||

| Variables | Mean | s.d. | OC | OCB | PJ | PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Commitment | 22.43 | 2.971 | 1 | |||

| OCB | 42.90 | 5.829 | 0.733 | 1 | ||

| Person-J Fit | 16.42 | 2.763 | 0.553 | 0.586 | 1 | |

| Psychological Empowerment | 23.98 | 3.798 | 0.640 | 0.750 | 0.659 | 1 |

Table 2 shows the results of the convergent and discriminant validity test on the statement items of variables in this study. Convergent validity can be seen at the loading factor value of each indicator of the construct. All question items of all variables are valid due to the loading factor ≤ 0.7. All question items meet the criteria for the discriminant validity since the loading factor> cross-loading factor. Therefore, all questions can measure the problems of the study. Reliability testing presents the concept measurements is consistent without any bias with composite reliability and Cronbach's alpha value are above 0.7. Then, Table 3 shows that the instruments of this study have met the reliability test requirements. Thus, the instruments are declared valid and reliable for further hypotheses testing.

| Table 2: Outer Model (Weights or Loading) | ||||

| Organizational Commitment | OCB | P-J Fit | Psychological Empowerment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC1 | 0.877 | 0.660 | 0.489 | 0.574 |

| OC2 | 0.926 | 0.694 | 0.511 | 0.618 |

| OC3 | 0.732 | 0.446 | 0.329 | 0.395 |

| OC4 | 0.806 | 0.603 | 0.521 | 0.523 |

| OC5 | 0.861 | 0.649 | 0.449 | 0.553 |

| OCB1 | 0.548 | 0.819 | 0.429 | 0.582 |

| OCB2 | 0.656 | 0.827 | 0.493 | 0.552 |

| OCB3 | 0.663 | 0.847 | 0.440 | 0.590 |

| OCB4 | 0.572 | 0.741 | 0.470 | 0.581 |

| OCB5 | 0.611 | 0.851 | 0.510 | 0.601 |

| OCB6 | 0.567 | 0.855 | 0.413 | 0.568 |

| OCB7 | 0.623 | 0.872 | 0.498 | 0.632 |

| OCB8 | 0.603 | 0.799 | 0.489 | 0.680 |

| OCB9 | 0.529 | 0.739 | 0.477 | 0.632 |

| OCB10 | 0.556 | 0.743 | 0.520 | 0.650 |

| PJ1 | 0.524 | 0.566 | 0.879 | 0.613 |

| PJ2 | 0.459 | 0.543 | 0.938 | 0.652 |

| PJ3 | 0.513 | 0.519 | 0.922 | 0.558 |

| PJ4 | 0.487 | 0.477 | 0.859 | 0.551 |

| PE1 | 0.678 | 0.652 | 0.608 | 0.723 |

| PE2 | 0.626 | 0.693 | 0.716 | 0.771 |

| PE3 | 0.441 | 0.545 | 0.412 | 0.827 |

| PE4 | 0.373 | 0.511 | 0.421 | 0.797 |

| PE5 | 0.288 | 0.458 | 0.375 | 0.746 |

| PE6 | 0.468 | 0.574 | 0.444 | 0.808 |

| Table 3: Composite Reliability Dan Cronbach’s Alpha | ||||

| Cronbach's Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Commitment | 0.897 | 0.911 | 0.924 | 0.710 |

| OCB | 0.941 | 0.942 | 0.950 | 0.657 |

| P-J Fit | 0.922 | 0.923 | 0.945 | 0.810 |

| Psychological Empowerment | 0.872 | 0.876 | 0.903 | 0.607 |

The Results of Hypotheses Testing

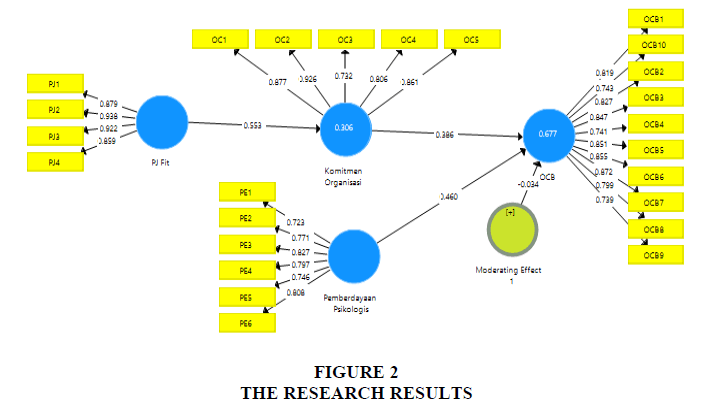

The study is to test the mediating and moderating mechanisms of P-J Fit on OCB. The mediating mechanism is with organizational commitment and the moderating mechanism is with psychological empowerment. SmartPLS 3.0 is used to calculate the testing. The results of the research can be seen in Figure 2 below;

Based on the study results in Table 4, it shows that the direct effect of P-J Fit on organizational commitment (β=0.553, p<0.001) has a t-value of 5.516>1.96, which is positive and high significance (H1 is accepted). The direct effect of organizational commitment on OCB (β=0.386, p<0.001) with a t-value of 5.485>1.96; it is positive and high significance (H2 is accepted). Furthermore, the mediation of organizational commitment to the effect of P-J Fit on OCB (β=0.213, p<0.001) has a t-value of 4.004>1.96, which means that organizational commitment can mediate the relationship between P-J Fit and OCB (H3 is accepted). Organizational commitment can affect OCB either directly or as the mediating one. Then, for the moderating mechanism, the p-value>0.10 with a t-value of 0.460<1.96 and β=-0.034; indicates a negative and insignificant relationship; psychological empowerment cannot moderate the relationship between P-J Fit and OCB (H4 is rejected).

| Table 4: The Research Results | |||||

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Commitment -> OCB | 0.386 | 0.388 | 0.070 | 5.485 | 0*** |

| Moderating Effect 1 -> OCB | -0.034 | -0.007 | 0.074 | 0.460 | 0.645 |

| P-J Fit -> Organizational Commitment | 0.553 | 0.546 | 0.100 | 5.516 | 0*** |

| P-J Fit -> Organizational Commitment -> OCB | 0.213 | 0.212 | 0.053 | 4.004 | 0*** |

Notes: ***=significant on a = 0.01(high significance); **=significant on a = 0.05 (significant); *=significant on a = 0.10 (low significance).

Discussion

The result of the research proves that P-J Fit has a direct positive effect on organizational commitment. It means that the more employees feel a match for their work, the higher their commitment to the organization. It supports the previous studies that P-J Fit is an important factor in driving employees’ organizational commitment (Chhabra, 2015; Soelton et al., 2020; Therasa & Vijayabanu, 2016). This research also proves that organizational commitment is an important aspect to improve employee extra-role behavior. When employees have loyalty and engagement to their organization, they tend to show OCB behavior. The results of this study support some previous studies (Farzaneh et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2018; Khaola & Sebotsa, 2015; Soelton et al., 2020; Srivastava & Dhar, 2016), which prove that the higher the employee’s commitment, the higher their OCB.

Organizational commitment does not only have a direct effect on OCB but it also mediates the relationship between P-J Fit and OCB. When an employee feels fit for the other employees and the jobs, it encourages engagement and loyalty to his organization. This condition indirectly encourages the employee to perform OCB. The results of this study support the previous studies stating that organizational commitment is the mediating variable between P-J Fit and OCB (Farzaneh et al., 2014). In the path correlation, P-O fit is proven to encourage organizational commitment, and this organizational commitment can also encourage employees’ OCB (Soelton et al., 2020). The results of this study also support the previous studies stating that organizational commitment plays an important role in facilitating the relationship of antecedent factors (such as; P-J Fit) and work outcomes (such as; OCB) (Chhabra, 2015; Paul et al., 2016). The relationship mechanisms displayed in this research prove that this research support self-identity theory and social exchange theory.

On the other hand, the moderation testing of psychological empowerment shows different results from the previous studies. Farzaneh et al. (2014) found evidence that psychological empowerment can moderate the effect of organizational commitment on OCB. The more employees feel psychological empowerment, the stronger the relationship between organizational commitment and OCB. However, the results of this study find an insignificant effect of psychological empowerment as the moderating variable to the effect of organizational commitment on OCB.

Several reasons may be used to answer this phenomenon. First, the previous studies massively did not treat psychological empowerment as the moderation (especially in the OCB mechanism). Psychological empowerment is proven to play an important role in OCB mechanisms, its roles can be either an antecedent or a mediation (e.g. Islam et al., 2016; Jin-liang & Hai-zhen, 2012; Macsinga et al., 2015; Newman et al., 2017; Seibert et al., 2011; Singh & Singh, 2019; Srivastava & Dhar, 2016). This study provides generalizations on previous researches (Farzaneh et al., 2014) by showing different results in different sectors.

Secondly, to understand why psychological empowerment does not play an important role in this research, it is necessary to return to the basic concept of psychological empowerment. Zimmerman (1995) reviews the basic concepts of psychological empowerment. In his review, Zimmerman (1995) states that psychological empowerment is formed from three basic components, i.e. intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral. The intrapersonal component refers to how people think about themselves, including self-efficacy, motivation to control, perceived competence, and mastery. Then, the interactional component refers to the understanding that a person has about their social environment (community), and their socio-political problems. This aspect indicates that the individual is aware of which behavioral choices or actions are appropriate to achieve goals in his or her social environment. Lastly, the behavior component refers to actions taken to directly affect outcomes.

These components combine to describe how individuals believe in their ability to influence a particular context (intrapersonal component), to understand how the system works in that context (the interactional component), and to engage in real behavior within that context (the behavioral component). Thus, if it only describes the intrapersonal component, then the view of psychological empowerment is incomplete (Zimmerman, 1995). It is a possibility that employees’ psychological empowerment is not balanced among those three components, especially in the behavioral component. It means that although employees have psychological empowerment if it is not implemented in behavior then it cannot strengthen the effect of commitment on OCB.

This is a prediction because this study does not examine the psychological empowerment with those three components. The different compositions of those components are predicted to greatly affect employees’ work outcomes. When those three components of psychological empowerment are not integrated, perhaps the employees’ work outcomes are also not optimum. It also supports the previous research (Chang & Liu, 2008) which shows that psychological empowerment has little effect on employee productivity.

Conclusion and Suggestion

It is concluded that P-J Fit plays an important role to encourage organizational commitment. Organizational commitment is also proven to encourage employees’ OCB. It is also concluded that organizational commitment plays an important role to facilitate P-J Fit in OCB. The organization needs to consider the compatibility between employees and their jobs to create extra-role commitments and behaviors benefitting the overall performance of the organization. This research contributes to supporting self-identity theory and social exchange theory. It is also found that psychological empowerment is not able to strengthen the effect of organizational commitment on OCB. It also proves that psychological empowerment may be more appropriately treated as an antecedent or a mediator in the mechanism of OCB. Furthermore; it is predicted that employees’ psychological empowerment is not optimal because of the incomplete or imbalanced components. It is suggested for further research to examine the different mechanisms in understanding OCB; especially psychological empowerment may be used as a mediation of proposed variable relationships. Then, it is also important to consider the components of psychological empowerment completely. It is also needed to test other mechanisms in different industrial contexts.

References

- Ardiç, K., Uslu, O., Oymak, Ö., Sakarya, Özsoy, E., & Özsoy, T. (2016). Comparing person organization fit and person job fit. Journal of Economics and Management, 25(3).

- Astakhova, M.N. (2016). Explaining the effects of perceived person-supervisor fit and person-organization fit on organizational commitment in the U.S. and Japan. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 956-963.

- Blau, P.M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Buyukyilmaz, O. (2018). Relationship between person-organization fit and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. International Journal of Management and Administration, 2(4), 135-146.

- Cable, D.M., & Derue, D.S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875-884.

- Carless, S. A. (2005). Person – job fit versus person-organization fit as predictors of organizational attraction and job acceptance intentions : A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 411-429.

- Chang, L., & Liu, C. (2008). Employee empowerment, innovative behavior, and job productivity of public health nurses : A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 1442-1448.

- Chhabra, B. (2015). Person - job fit: Mediating role of job satisfaction & organizational commitment. Indian Journal of Industrial Relation, 50(4), 638-651.

- Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment, and personal need non-fulfillment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53, 39-52.

- Farzaneh, J., Farashah, A.D., & Kazemi, M. (2014). The impact of P-J Fit and person-organization fit on OCB The mediating and moderating effects of organizational commitment and psychological empowerment. Personnel Review, 43(5), 672-691.

- Islam, T., Khan, M.M., & Bukhari, F.H. (2016). The role of organizational learning culture and psychological empowerment in reducing turnover intention and enhancing citizenship behavior. The Learning Organization, 23(2), 156-169.

- Jawad, M., Tabassum, T.M., Raja, S., & Abraiz, A. (2013). Study on work place behaviour: Role of person- organization fit, p-j fit & empowerment, evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Business and Management Sciences, 1(4), 47-54.

- Jha, S. (2014). Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment: Determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 3(1), 18-35.

- Jin, M.H., Mcdonald, B., & Park, J. (2018). does public service motivation matter in public higher education ? testing the theories of person – organization fit and organizational commitment through a serial multiple mediation model. American Review of Public Administration, 48(1), 82-97.

- Jin-liang, W., & Hai-zhen, W. (2012). The effects of psychological empowerment on work attitude and behavior in Chinese organizations. Journal of Business Managemen, 6(30), 8938-8947.

- Khan, S.K., Rashid, M.Z.H.A., & Vytialingam, L.K. (2016). The role of organisation commitment to enhancing organisation citizenship behaviour: A study of academics in malaysian private universities. International Journal of Economics and Management, 10(2), 221-239.

- Khaola, P.P., & Sebotsa, T. (2015). Person-organization fit, organisational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviour. Danish Journal of Management and Business Science, 67-74.

- Kim, J.S., & Gatling, A. (2019). Impact of employees ' job, organizational and technology fit on engagement and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(3), 323-338.

- Kristof, A.M.Y.L. (1996). Person-organization fie an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49.

- Kristof-brown, A.L., Zimmerman, R.D., & Johnson, E.C. (2005). Consequences of individuals ’ fit at work : A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281-342.

- Lambert, E.G., Hogan, N.L., & Griffin, M.L. (2008). Organizational citizenship behavior and commitment among correctional staff. Criminal Justice And Behavior, 35(1), 56-68.

- Macsinga, I., Sulea, C., Sârbescu, P., Fischmann, G., Dumitru, C., & To. (2015). Engaged, committed, and helpful employees: The role of psychological empowerment. The Journal of Psychology, 149(3), 263-276.

- Newman, A., Schwarz, G.B.C., & Sendjaya, S. (2017). How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1), 49-62.

- Obedgiu, V., Bagire, V., & Mafabi, S. (2017). Examination of organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour among local government civil servants in Uganda. Journal of Management Development, 36(10), 1304-1316.

- Organ, D.W. (1994). Personality and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Management, 20(2), 465-478.

- Paul, H., Bamel, U.K., & Garg, P. (2016). Employee Resilience and OCB: Mediating Effects of Organizational Commitment. The Journal for Decision Makers, 41(4), 308-324.

- Podsakoff, P.M., Ahearne, M., & Mackenzie, S.B. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 262-270.

- Rayton, B., Yalabik, Z.Y., & Rapti, A. (2019). Fit perceptions, work engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(6), 401-414.

- Seibert, S.E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S.H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations : A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981-1003.

- Sesen, H., Soran, S., & Caymaz, E. (2014). Dark side of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB ): Testing a model between OCB, social loafing, and organizational commitment. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(5), 125-135.

- Singh, S.K., & Singh, A.P. (2019). Interplay of organizational justice, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job satisfaction in the context of circular economy. Management Decision, 57(4), 937-952.

- Soelton, M., Noermijati, N., Rohman, F., Mugiono, M., Noviandy, I., & Siregar, R.E. (2020). Reawakening perceived person organization fit and perceived person job fit: Removing obstacles organizational commitment. Management Science Letters, 10, 2993-3002.

- Spreitzer, G.M. (1995). Psychological, empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442-1465.

- Srivastava, A.P., & Dhar, R.L. (2016). Impact of leader member exchange, human resource management practices, and psychological empowerment on extra role performances: The mediating role of organisational commitment. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(3), 351-377.

- Straatmann, T., Königschulte, S., Hattrup, K., & Hamborg, K.C. (2020). Analysing mediating effects underlying the relationships between P – O fit, P – J fit, and organisational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1533-1559.

- Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65-93.

- Teimouri, H., Dezhtaherian, M., & Jenab, K. (2015). Examining the relationship between person-organization fit and organizational citizenship behavior: The case of an educational institution. Annals of Management Science, 4(1), 23-44.

- Therasa, C., & Vijayabanu, C. (2016). Person - job fit and the work commitment of IT Personnel. J Hum Growth Dev, 26(2), 218-227.

- Van Loon, N.M., Vandenabeele, W., & Leisink, P. (2017). Clarifying the relationship between public service motivation and in-role and extra-role behaviors: The relative contributions of person-job and person-organization fit. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(6), 699-713.

- Zimmerman, M.A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581-599.