Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

E-Government's Effect on Corruption Reduction in Indonesian Local Government Bureaucracy: A Case Study in Central Java

Martitah, UNNES

Slamet Sumarto, UNNES

Widiyanto, Universitas Terbuka (UT)

Abstract

Indonesia's protracted path toward e-government, which began in 2001 with the establishment of several infrastructure needs, was ultimately declared complete in 2018 with the declaration of the inaugural phase of e-government implementation at all levels of government. Indonesia chose e-government in general for three reasons: to capitalize on information technology breakthroughs for development, to boost government efficiency, and to decrease bureaucratic corruption. Based on field research, this essay proposes that implementing e-government in local government in Indonesia promotes government transparency, accountability, and public scrutiny. As a result, corruption has been drastically decreased in the licensing of firms and the procurement of products and services by local governments. This is because all government service operations and purchases of goods and services are transparent, ensuring that all stakeholders are kept informed throughout the licensing and procurement processes for products and services. Additionally, the local government governor's political will to use social media to engage the people in controlling the local government machinery contributes greatly to reducing corruption in the local government bureaucracy.

Keywords

E-Government, Local Government, Business Licencing, E-Procurement, Corruption

Introduction

Indonesia's Corruption Perception Index in 2019 was ranked fourth in Southeast Asia. The score that Indonesia got was 40 points, up 2 points from 2018 which was 38 points. Singapore is the country in Southeast Asia with the highest Corruption Perception Index of 85 points. There are more than 180 countries whose corruption perception index is assessed by Transparency International. On a global scale, Indonesia is still ranked 90th out of 180 countries. Theoretically, the closer to 100 the value of the Corruption Perception Index from a country, the level of corruption in that country is getting smaller or even cleaner (Hariyanto, 2020; Jayani, 2020).

The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) in its study stated that there are six sectors that are prone to corruption in Indonesia. First, the goods and services procurement sector, which has so far been the result of KPK's action, no less than 121 regents/mayors and 21 governors have been involved in corruption cases due to fees for the procurement of goods and services. The second area that is prone to corruption is bureaucratic reform policies, particularly transfers, rotations, and employee recruitment. Third, granting business licenses, especially mining. Fourth, mark-up development projects. Fifth, the receipt of project fees. Sixth, collusion for the approval of the Regional Revenue and Expenditure Budget (APBD) [between the regent/governor and the Regional People's Representative Assembly [DPRD] (Winata, 2020).

In light of the on-going corruption pandemic that has infected government bodies in Indonesia, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has urged local governments around the country to improve synergies and increase effectiveness in preventing and eradicating corruption (Winata, 2020). This is reinforced by the statement of former KPK Chairman Erry Riyana Hardjapamekas, who stated that efforts to eradicate corruption must take a three-pronged approach, namely (1) investigation and prosecution of corruption crimes; (2) system improvements to prevent future corruption; and (3) public education and community empowerment (Hardjapamekas, 2017).

According to Erry Riyana, one strategy for efficiently eradicating corruption is to enhance the government system's capacity to avoid corruption as a preventive measure through the use of information technology as a vehicle for establishing electronic governance (e-Government). Numerous studies demonstrate a positive correlation between e-Government and the elimination of corruption inside the government (Cho & Choi, 2004; Ke & Wei, 2004; Ministry of Finance Singapore, 2013; Ojha et al., 2009).

In this regard, Indonesia has been preparing a government transformation from traditional to digital through the use of information technology since 2001. The lengthy path through four decades of government, with numerous rules enacted, culminated in the publication of an e-Government Blueprint that included six possibilities for its implementation in Indonesia. Additionally, the e-Government Blueprint identifies at least four government services whose implementation can be facilitated by an electronic system: Community Services, Regional Financial Personnel, and Asset Management (Departemen Komunikasi dan Informatika RI, 2016).

However, according to the findings of Setyobudi & Styoningrum's research, e-Government in Indonesia does not contribute significantly to the increase in the country's Corruption Perception Index (CPI). This is because the existing e-Government does not only promote contact and information exchange between the government and the population, despite the fact that the Human Resources (HR) responsible for its operation are highly skilled in the field of information technology. This is in contrast to industrialized countries, where e-Government has advanced to the transaction and transformation phases, having a considerable impact on the country's GPA growth (Christan, Setyobudi & Setyaningrum, 2019).

Other studies have also shown similar results. E-Government that exists today actually provides a wider space for transparency and public control over governance. However, because there are a number of regulations that have the potential to threaten civil liberties in expressing their opinions, they are worried about voicing corrupt practices carried out by state apparatus or public officials (Simarmata, 2017).

This study empirically confirmed at the local government level, particularly in Central Java, the influence of e-government on reducing corruption in local government bodies. Central Java was chosen as the sample province because it has consistently performed well in eradicating corruption according to the Eradication of Corruption Commission (ECC) also as a champion in the Ministry of Government Apparatus Empowerment and Bureaucratic Reform's Electronic-Based Government System index (Inspektorat Provinsi Jawa Tengah, 2020). The Governor of Central Java, Ganjar Pranowo, stated that the award demonstrated the Central Java Provincial Government's commitment to implementing the Government Resources Management System (GRMS), which has migrated from a paper-based to an electronic-based bureaucracy, and in particular to carrying out three government functions: serving the community, business, and other governments (Diskominfo Jawa Tengah, 2019).

According to this article, the deployment of e-government in local government in Indonesia has a good effect on the government's transparency, accountability, and public oversight. As a result, corruption in business licensing, procurement of goods and services, and other areas of local government is significantly decreased. This is because all government service operations and purchase of products and services are transparent, allowing all parties to see what is happening at each stage of licensing and procurement.

The article is structured as follows. Following an overview of the setting, the research methodology for this work is discussed. Following that, we will review recent advancements in related studies, followed by a discussion of corruption's evolution and dynamics in Indonesia. The following debate will focus on public trust in law enforcement officials in Indonesia's fight against corruption. Following that, a discussion of the role of e-government in reducing corruption in local government bureaucracy will take place, followed by a conclusion.

Methodology of Research

The data for this study were gathered through interviews with a variety of informants in several districts and cities in Central Java who were involved in the operation of e-government, including the Office of Communication and Information, Procurement of Goods and Services, and an online single submission unit that handles all forms of government licensing, including licensing for business or investment. Secondary data is derived from online sources such as news stories, journal publications, and government websites in Central Java. After collecting all data, it was evaluated qualitatively using content analysis methodologies to determine the answers to the study questions.

Literature Review

One way to increase the effectiveness of anti-corruption measures is to improve the government system's capacity to prevent corruption through the use of information technology as a tool for implementing Electronic Governance (e-Government) (Hardjapamekas, 2017). According to a study done by Cho & Choi, the Seoul Metropolitan Regional Administration's success in eradicating corruption in its government is due to its transition from traditional to computerized government, dubbed the OPEN System. The acronym OPEN System refers to (Online, Procedures, and Enhancement for civil applications) (Cho & Choi, 2004). Seoul's e-Government model, which utilizes the OPEN system, has been shown to be efficient in combating corruption in the city (Park & Kim, 2019).

The OPEN System is a web-based government service available to the citizens of Seoul for the purpose of applying for licenses, registrations, procurement of goods and services, and contracts (Kim & Cho, 2005; Park & Kim, 2019). Not only do citizens benefit from the convenience, affordability, and speed of government services, but they can also watch the development of services processed by the government in real time, including the calculation of required time and prices (Cho & Choi, 2004).

Meanwhile, Ojha, Palvia & Gupta bolster the notion that e-Government is the most effective and promising weapon for eradicating corruption in government today and in the future (Ojha et al., 2009). Transparency and availability of access to information are the primary characteristics of an electronic-based government system, which is often regarded as the most effective tool for avoiding corruption, particularly in European Union member nations (Lupu & Lazar, 2015). Similarly, Singapore is the 'cleanest' country in terms of corruption, according to the results of Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index in 2019, because the country has reached 92 percent of all government services being conducted online (Ke & Wei, 2004; Ministry of Finance Singapore, 2013).

However, the findings of Setyobudi & Styoningrum demonstrate the 'failure' of e-government in Indonesia, which has thus far contributed insignificantly to the country's Corruption Perception Index growth (CPI). This is because the existing e-government does not only allow contact and information exchange between the government and the people, despite the fact that the Human Resources (HR) responsible for the e-government are extremely knowledgeable in the field of information technology. Its influence on corruption reduction, for example in Kazakhstan, is limited to minor acts of corruption such as bribes (Sheryazdanova & Butterfield, 2017). This is in contrast to developed countries, where e-government has advanced to the transaction and transformation phases, having a considerable impact on the country's CPI growth (Christan, Setyobudi & Setyaningrum, 2019). Additionally, Paramitha Saha et al., previously stressed that e-government benefits more from providing pleasing services to the community in three ways: quality, efficiency, and responsiveness (Saha et al., 2010).

This is in contrast to developed countries, where e-government has advanced to the transaction and transformation phases, having a considerable impact on the country's GPA growth (Christan, Setyobudi & Setyaningrum, 2019). Additionally, Paramitha Saha, et al., previously stressed that e-government benefits more from providing pleasing services to the community in three ways: quality, efficiency, and responsiveness (Saha et al., 2010).

Other research has produced similar findings. Today's e-Government enables a greater degree of openness and public influence over governance. However, because a variety of rules may jeopardize their civil liberties in expressing their ideas, people are fearful of speaking out against corrupt acts by the state apparatus or public authorities (Simarmata, 2017). Numerous impediments to e-government development ultimately demand political commitment. According to Richard Schwester, political support is critical and a determinant of effective e-government implementation (Schwester, 2009).

The 'failure' of e-government in a country is due to two factors: its use is restricted to interactive contact and information exchange between the government and the public. Additionally, the inconsistency between other legal norms and e-government legislation (Indonesia). Despite Indonesia's 'lack of success' in reducing corruption through e-government, Mistry and Jalal demonstrate that e-government continues to have a substantial impact on reducing corruption in government bodies, particularly in developing nations, in their 2003-2007 study. Whereas it is less influential in industrialized countries, where the existing system has been able to fight corruption. The two academics' belief is based on the benefits of e-government in terms of facilitating the development of transparent and accountable policies through the use of information technology (Mistry & Jalal, 2012). As a result, Evans and Yen underline that e-government necessitates a shift in the way government interacts with the community, cultural sensitivity, and the critical attitude of the populace (Evans & Yen, 2006).

Neupane, Soar, Vaidya & Young, in particular, ensure that the government employs electronic procurement with automation and tracking systems to increase openness and accountability in the purchase of government goods and services, hence reducing corruption (Neupane et al., 2012). However, Park and Kim stressed that simply implementing e-government does not inevitably reduce a country's corruption level. According to their study, only a country with a strong legal system and an open government system will be able to successfully reduce corruption. On the other side, a country that has an effective legal system and an opaque administration will not benefit from the use of e-government (Park & Kim, 2019). Cleveland et al. noted that efforts to combat bribery and corruption can be carried out on an international level using three strategies: anti-bribery law, which the United Nations has adopted through a number of anti-bribery and anti-corruption agreements. Additionally, the role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) such as Transparency International (TI) and the World Economic Forum (WEF), which publish regular reports on the state of corruption in each country, is quite effective at inspiring countries to make systemic changes to reduce, if not eliminate, corruption. The following factor is the existence of a complaint procedure, which is particularly important for global corporations (Cleveland et al., 2009).

Several of these studies examine the circumstances and conditions that influence the success or failure of e-government in reducing corruption in the public sector bureaucracy. E-government can have a beneficial effect on eradicating corruption in the government bureaucracy by using the following e-government methods: a. e-government is implemented in real time, allowing the public to monitor the progress of government services, both in terms of time and cost (OPEN System Seoul) b. e-government is widely used in Singapore's government service system c. Transactions and transformation are included in e-government (developed nations) d. Political backing is critical for the successful implementation of e-government. Effective legal system and transparent government Apart from several success stories of implementing e-government in reducing a country's corruption level, there is a less successful experience of implementing e-government when its use is limited to interaction and information about government work with the community. Although there is no effect on reducing petty corruption inside the government bureaucracy, this is owing to the government's increased transparency and accountability via information technology. Additionally, countries without a competent legal structure, even if they adopt e-government, may not always succeed in decreasing corruption.

Corruption In Indonesia: Recent Developments

The Recent of Indonesia’s CPI Position

The Corruption Perception Index is one of the instruments used to determine a country's level of corruption. The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) was established in 2005 by Transparency International (TI), a non-governmental organization whose aim is to 'promote' poverty caused directly or indirectly by corruption (Urueña, 2018). The CPI is an annual study published by Transparency International on the perception of corruption, not actual corruption in a country and is based on a poll of expert perceptions in a variety of industries (Budsaratragoon & Jitmaneeroj, 2020; Paulus & Kristoufek, 2015). Although academics have criticized the CPI methodology, the CPI has established a global standard for determining a country's level of corruption. Additionally, the findings have a significant impact on the policy decisions made by donor countries toward developing countries (Baumann, 2020).

In this regard, the next part will discuss the latest trends in Indonesia's CPI and its comparison to other ASEAN countries in order to ascertain the corruption dynamics in the country. As illustrated in Graph 1, the rate of development of Indonesia's CPI increased gradually from 2012 to 2019, with an average increase of one to two digits. Indonesia's CPI was ranked 32 in 2012 and reached a peak of 40 in 2019, before falling three points to 37 in 2020. According to the CPI data, the closer a country's CPI score is to 100, the lower its level of corruption. According to these theoretical factors, Indonesia's CPI score indicates that corruption remains high (Transparency International, January 28, 2021).

Meanwhile, Indonesia's CPI is ranked fourth in ASEAN with a score of 37. Ironically, Timor-Leste, a recently constituted country, was able to outperform Indonesia's CPI with a score of 40. Meanwhile, Singapore surpassed other ASEAN countries, notably Malaysia, which is ranked second with a CPI score of 51 (Transparency International, January 28, 2021). According to observers, the decrease in Indonesia's CPI index will erode public trust in the country's environment for eradicating corruption, governance, and investment, as well as economic conditions (Rizki, 2021). Meanwhile, according to J Danang Widoyoko, Secretary General of Transparency International Indonesia, the drop in Indonesia's CPI score in 2020 demonstrates that a number of government policies that prioritize commercial and investment interests over integrity can only result in corruption. Additionally, in terms of responding to the current Covid-19 epidemic (Suyatmiko & Nicola, 2021). One type of corruption that has not been totally eradicated from the government bureaucracy is bribery of government officials during the licensing and procurement of goods and services, which has a negative impact on the Indonesian CPI's performance in general.

The Government Bureaucracy's Bribery Case

During the sixteen-year (2004-2020) journey of Indonesia's anti-corruption campaign, bribery of public officials or state apparatus became the most prevalent form of corruption. Graph 4 shows that bribery cases in Indonesia have increased steadily since 2004 when there were 25 cases, peaking at 168 cases in 2018, before declining in the following two years (2019-2020), with the total number of bribery cases handled by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) reaching 739 in January 2020.

There are three sectors where bribery is most prevalent among the public when dealing with government officials: the health care sector (up to 49 percent); and the financial services sector (up to 49 percent). Bribery was committed as a result of a nepotistic relationship with government officials. Additionally, the second highest rate of bribery of government officials occurs in government administration services at 46%, which is accomplished through the exchange of cash or gifts. Finally, what is remarkable is that the same strategy is used in the education sector, particularly public schools, which are actually under the authority of the Regional Government, by rewarding teachers and school administrators with cash or presents. Meanwhile, the industry with the lowest likelihood of bribing government officials is legal affairs services, at 3%. Additional sectors where government personnel are prone to bribery include the police, public universities, and while seeking for jobs in government departments.

Meanwhile, bribery in government administration services involving cash is the most prevalent practice in two organizations, namely the police and government administration services, with each reaching a rate of 16 percent. Bribery with payment to obtain employment in a government office reached 7%, followed by health services, schools, and state campuses at 6% each, and legal services at 3%. (LSI, December 10, 2018).

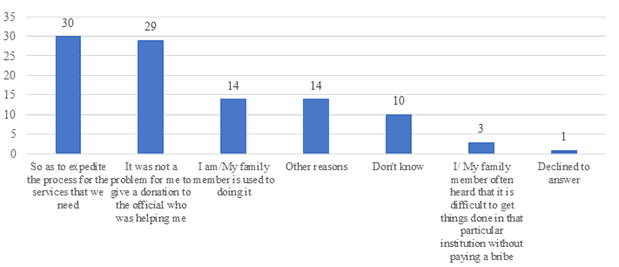

What is the reason that people feel 'compelled' to bribe government employees who provide public services even when they do not request it? As illustrated in Graph 1, there are two primary reasons why people are 'compelled' to bribe: the first is to accelerate the administration of public services by 30%, and the second is the improper nature of giving by 29%. Another factor is that 14 percent of family members have experience with bribing government officials.

These statistics demonstrate that the quality of public services in Indonesia is inadequate and prone to corruption via bribery. Whereas the Ministry of State Apparatus Empowerment and Reform established a Regulation on Public Service Standards Guidelines in 2014. The regulation's prologue emphasizes that every public service provider is required to compile, specify, and implement Service Standards and Service Declarations while taking into account the organizers' capacity, community requirements, and environmental conditions.

The rule defines Service Standards as a guideline for service delivery and a reference point for evaluating service quality as a responsibility and promise made by the organizer to the community in the context of providing quality, rapid, easy, inexpensive, and measurable services. The Public Service Standards are founded on six principles: simplicity, participation, accountability, sustainability, transparency, and fairness. Thus, three potential sources of bribery must be foreseen in the provision of public services: regular service methods with defined Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), the duration of the needed service from start to finish, and fees charged to recipients. The service provider and the service recipient community must agree on the level of service (Chapter III: 5). Corruption in services continues to arise as a result of violations of the Guidelines for Public Service Standards.

Figure 1: Graph 1: Reasons for Bribing Government Officials-Even if not Requested 2018

Source: LSI. (December 10, 2018). Share of respondents who gave the following reasons for bribing government officials even without being asked to, in Indonesia as of October 2018 [Graph]. In Statista.

Another example of government corruption is when citizens give more money than the established normal fee for public services. The purpose for charging higher service fees is to expedite the process of administrative services required by the community, which totals 61 percent. Following that, due to the community's 'fear,' if they do not contribute more money, administrative matters will not be processed according to their wishes by 14%. Meanwhile, other factors include that providing more compensation to government officials is a bureaucratic culture (10 percent), the purpose for remuneration (8 percent), and the community believes that the additional compensation provided to government officials is minimal (4 percent) (LSI, December 10, 2018).

The acute problem of bribery in government has parallels with China's bribery. However, bribery is extended in China to the 'culture' of gift giving. Giving gifts to someone [in any position] demonstrates the genuineness of personal ties in Chinese society (Cleveland et al., 2009). When gifts are offered to government officials, the issue becomes murky, as the lines between 'talih asih' friendship and the personal motive behind the gift are frequently blurred in Chinese society (Steidlmeier, 1999). Except for the tenacity of law enforcement authorities in eradicating bribery, there is no other endeavour to abolish bribery in the government bureaucracy that is wrapped in a culture of compassion. As a result, law enforcement must earn the public's trust.

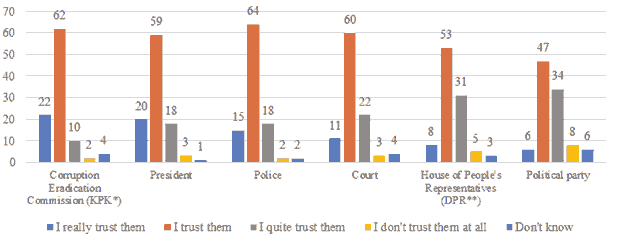

The Public's Confidence in Law Enforcement Offices

As previously stated, Indonesia's declining CPI has a negative effect on public faith in the government. Graph 2 demonstrates that, on average, people believed in numerous legal and political institutions in Indonesia under the administration of President Joko Widodo (2016-2019), even though none were truly trusted. The police institution is the most trusted by the public, with a level of trust of 64 percent, followed by the KPK at 62 percent, but true trust stands at 22 percent, the highest level of any state agency. Meanwhile, political parties have the lowest amount of public trust, at 34%.

Figure 2: Graph 2: Public Trust in State Institutions Under the Joko Widodo Administration, 2016-2019

Source: LSI. (August 29, 2019). Level of trust in government agencies in Indonesia during Joko Widodo's era from 2016 to 2019, by type [Graph]. In Statista.

According to the data, the public continues to place a high premium on law enforcement organizations such as the KPK, the Attorney General's Office, the Police, and the Courts. This public trust is undoubtedly a social mode that motivates these law enforcement authorities to take a proactive role in Indonesia's fight against corruption. Especially in this day and age of information technology, the public's role in supervising the work of these law enforcement organizations becomes even more vital.

The Impact of E-Government on Local Government Corruption

E-Government Policy in Indonesia

Since 2001, Indonesia has been preparing to change its government from a traditional to a digital one through the use of information technology. The lengthy path through four decades of government, with numerous rules enacted, culminated in the publication of an e-Government Blueprint that included six possibilities for its implementation in Indonesia. Additionally, the e-Government Blueprint identifies at least four government services whose implementation can be facilitated by an electronic system: Community Services, Regional Financial Personnel, and Asset Management (Departemen Komunikasi dan Informatika RI, 2016).

Indonesia, as a developing country entering the democratic period, is committed to establishing a transparent, responsible, and participatory government system. One of the initiatives made by Indonesia is to leverage information technology in order to create a more effective and efficient nation and state. This is reinforced by Presidential Regulation No. 3 of 2003 on the National Policy and Strategy for E-Government Development. This Presidential Regulation reflects the Government's reaction to the public's demand for more effective, efficient, simple, affordable, and timely government services. Additionally, the advent of e-government in Indonesia provides a direct line of communication between the public and the government.

Numerous central and local government entities are currently pursuing the development of public services via communication and information networks. Even a number of regional chiefs, at least in Java, actively engage with the community via social media. According to the Ministry of Communication and Information's findings, the bulk of government sites and autonomous regional governments are at the first level (preparation), with just a tiny percentage reaching level two (maturation).

Meanwhile, levels three and four (consolidation & utilization) remain unachieved. More detailed observations from the ministry of communication and information indicate that the program has not demonstrated a positive tendency for the development of e-government. Several significant flaws include the following (Departemen Komunikasi dan Informatika RI, 2016): a. The services supplied through the government website are not supported by an effective management system or work process because regulations, procedures, and limited human resources severely restrict computer penetration into the management system and government work processes; b. not yet formulated strategy and insufficient funds allotted to each agency for e-government development; c. These initiatives are the result of individual agencies' efforts; consequently, a number of factors such as standardization, information security, authentication, and various basic applications that enable reliable, safe, and reliable interoperability between sites for the purpose of integrating management systems and work processes in government agencies into integrated public services have received less attention. Individual approaches are insufficient to close the gap in the community's ability to access the internet network, limiting the breadth of public services developed.

According to study conducted by Novi Prisma Yunita and Rudi Dwi Aprianto until 2018, Indonesia is particularly slow in developing e-government (Yunita & Aprianto, 2018). This is because of difficulties in data synchronization and sharing amongst government departments. This issue is exacerbated by the still-growing sectoral ego in government units, where each is focused exclusively on its own performance, rather than on the spirit of collaboration required to accomplish government goals (Hadinagoro, 2020).

The Indonesian government published Presidential Regulation No. 95 of 2018 on the Electronic-Based Government System in 2018 (SPBE). This Presidential Regulation automatically compels' all government units to synchronize their data in order to facilitate communication between them, especially between the national and regional administrations. The spirit of this Presidential Regulation is to establish a transparent, efficient, and responsible government system and to facilitate access to public services.

The Impact of Regional e-Government on Corruption Reduction

Prior to the widespread use of e-government in Central Java, corruption cases in the region were quite high. This is because; according to the 2018 'corruption action trend' reported by Indonesian Corruption Watch (ICW), there were 36 cases involving 65 suspects in 2018. State losses totaled Rp. 152.9 billion. Central Java is one rank below East Java, with 52 corruption cases involving 135 suspects and Rp 125.9 billion in public losses. Indeed, ICW's assessment of Central Java's corruption trend is more rigorous than it was in 2017, when Central Java ranked fourth in the number of corruption prosecutions with 29 instances and a total of Rp 40.3 billion in state losses (Tenola, 2019).

Based on the findings of a study done by the Semarang City Community Movement against Corruption (GMPK) on data on the fight against corruption in 35 regencies and cities in Central Java in 2019. 95 cases of corruption (tipikor) were successfully prosecuted. There are five regions in Central Java with the highest number of corruption disclosures, namely Klaten, Semarang, Kendal, Kebumen & Sragen (Mulyono, 2020).

The adoption of the Electronic-Based Government System (SPBE) in local government, as stipulated by Presidential Regulation No. 95 of 2018, is gradually bringing about significant changes in local government governance and culture in Indonesia. This fact is evident from the research team's field work in eight of Central Java's thirty-five districts and cities. Local governments that are subject to Regional Regulations on Electronic-Based Government Systems (SPBE), such as Batang, Semarang, Wonogiri, Tegal, Kudus, Pemalang, Semarang City & Salatiga Regencies, have consistently improved their Corruption Perception Index between 2018 and 2020, hovering in the 3.5-4 scale range. This circumstance has a negative impact on Central Java Province's Corruption Perception Index (GPA), which currently ranks highest in Indonesia according to the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission's (KPK) evaluation for 2019-2020 (Diskominfo Jawa Tengah, 2019; Inspektorat Provinsi Jawa Tengah, 2020).

The constancy of an increase in a number of local governments' Corruption Perception Index (CPI) was identified by stakeholders of some of these local governments as a result of the application of SPBE in governance in their regions. Prior to 2018, the government's internet-based system operated in a one-way fashion, displaying public information via local government websites. However, informants agreed that after the introduction of SPBE policies that integrated numerous existing service systems, such as e-procurement and Online Single Submission (OSS), efficiency, transparency, and increased public participation in government increased.

Meanwhile, they sense a substantial drop in the practice of gratification, bribery, and illegal levies, as stated by the Communication and Information Service, One Stop Service Office, and Online Single Submission (OSS) in Central Java's eight regencies and cities. On the other side, public confidence in and satisfaction with government services is increasing. This finding is consistent with the findings of other earlier research, which indicate that e-government increases public trust in the government and is capable of reducing corruption on a modest scale (Lupu & Lazar, 2015; Park & Kim, 2019). This is entirely rational, as e-government in Indonesian local governments has thus far been confined to the transfer of legacy systems that are still physically present in service and applications for procurement of goods and services to be conducted online. While the transaction procedure remains traditional, it is not entirely electronic.

However, efforts to create e-government in Central Java, which are being driven directly by Governor Ganjar Pranowo, are beginning to bear fruit in terms of combating corruption inside the Central Java government bureaucracy. The Corruption Eradication Commission's (CEC) Integrity Assessment Survey, released on Tuesday (1/10/2019), ranked the Central Java Government as the best in the anti-corruption fight. Alexander Marwata, Deputy Chairperson of the KPK, explained that the survey, which identified Central Java as the province with the most integrity, was conducted by the KPK's Directorate of Research and Development with assistance from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) over a 12-month period, from July 2017 to July 2018. The poll was conducted using in-depth interviews and random sampling. A representative sample of responses. Along with 120 internal and external respondents, the study drew the participation of ten expert respondents. According to the Corruption Eradication Commission, components of organizational culture such as bribery, gratuities, and the existence of brokers are considered in the study. Additionally, the KPK assesses each agency's anti-corruption system and human resource management, as well as the system's effectiveness in pressing someone not to commit a crime. As a result, Central Java was ranked #1 by the KPK, with a score of 78.26. East Java is in second place with a score of 74.96, followed by West Sumatra in third place with a score of 74.63. While West Java is ranked seventh with a 72.97 score, DKI Jakarta is ranked ninth with a 68.45 score (Humas Jateng, 2019).

Central Java Province's initial achievement in decreasing corrupt practices in the government bureaucracy cannot be isolated from the Governor of Central Java's active engagement in leading the clean local government movement through the construction of the Central Java e-government system. Ganjar has taken four efforts to combat corruption in Central Java's government bureaucracy (Humas Jateng, 2019). To begin, we will improve the public service system by transforming it from analog to digital systems, specifically by introducing e-government, e-budgeting, gratification management, and LHKPN reporting to public services via social media. As a result, anyone has access. Even Central Java's LHKPN obtained 100 percent reporting from tiers 1 to 4 and 100 members of the Central Java DPRD in 2018. Central Java authorities routinely claimed getting gratuities from the KPK, which were decreasing in number year after year.

Second, Ganjar holds employment auctions to discourage the widespread practice of purchasing and selling positions in local administrations. The auction of this position is part of the Central Government's on-going support for bureaucratic reform. Thirdly, once the system has been redesigned and digitized, the community will be involved in its oversight. In terms of community oversight, Ganjar requires that all agencies under the Provincial Government of Central Java establish social media accounts. Indeed, the number one person in Central Java had sacked an employee in response to public reports. Along with supervision, social media serves as a community service space. Not a handful of his provincial governments terminated the State Civil Apparatus for perpetrating illegal levies, owing to public allegations.

Fourth, and maybe most fundamental in the anti-corruption effort, is the leadership's example. Ganjar compared the anti-corruption movement to a person showering with a dipper; the first section of the body to be watered is the head, or the top portion. As a result, the governor intervened immediately to avoid corruption by restructuring the Central Java inspectorate and Human Resources Development Agency (BPSDM) to make them the best in the country.

The strategy of corruption eradication used by Governor Ganjar Pranowo in Central Java demonstrates a strong correlation between leadership and corruption eradication. This also demonstrates that in Indonesia's paternalistic cultural system, the leader's example has a significant influence on his subordinates. In this context, Ganjar serves as a shining example of how to eradicate corruption in Indonesia, despite the fact that Ganjar's policy is a carbon copy of President Joko Widodo's approach to overhauling the government bureaucracy. President Joko Widodo has used two approaches to implement bureaucratic change, particularly the auction of public positions for heads of government institutions. In essence, everyone has an equal opportunity to be elected as the leader of a government agency in an auction, as long as they meet the auction's eligibility requirements. Thus, you are not required to 'queue' for an extended period of time in accordance with the bureaucratic career sequence. This endeavour was made to identify candidates for future bureaucratic leaders but was unable to do so owing to bureaucratic requirements. President Joko Widodo's second approach is 'blusukan,' which entails going directly to the community and its bureaucracy to verify that all systems established are obeyed and run by their subordinates. Typically, President Joko Widodo leaves his office during these 'blusukan' festivities to make an unplanned visit (Pratiwi & Nurani, 2019; Tapsell, 2015).

This strategy has been adopted by a number of regional leaders in recent years, notably Governor Ganjar Pranowo. However, as social media has expanded, the structure of supervision and community participation has become more efficient. In this scenario, Ganjar Pranowo exemplifies Central Java’s ‘mobile government' paradigm. This is evident from Ganjar's daily tweets, which detail his actions as the governor of Central Java, including receiving public complaints about corrupt practices in the licensing and public service departments of specific government entities.

Conclusion

Central Java Province's effectiveness in decreasing corruption within the government bureaucracy is affected by the use of e-government in public services, company licensing, and procurement of products and services. Since 2018, the Central Java government has continued to create an e-government system, led directly by the Governor of Central Java. Along with the widespread use of social media in the community, the Central Java Government, beginning with Governor Ganjar Pranowo, has used it as a medium for public oversight of the performance of government agencies throughout Central Java while also absorbing people's aspirations for development. This reality demonstrates that while transforming the government system from a traditional physical one to a digitalized or online one is necessary for reducing corrupt practices in the local government bureaucracy, the example set by Governor Ganjar Pranowo also has a significant impact on reducing corruption. Government bureaucracy's unscrupulous practices This is because Governor Ganjar requires all government stakeholders he leads to use social media in order for the public to exercise oversight of government performance, including when instances of corruption are discovered in public service processes, business licensing, and procurement of goods and services within the Java Regional Government. Middle.

References

- Baumann, H. (2020). The corruption perception index and the political economy of governing at a distance. International Relations, 34(4), 504–523.

- Budsaratragoon, P., & Jitmaneeroj, B. (2020). A critique on the corruption perceptions index: An interdisciplinary approach. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 70.

- Cho, Y.H., & Choi, B.D. (2004). E-government to combat corruption: The case of Seoul metropolitan government. International Journal of Public Administration, 27(10), 719–735.

- Cleveland, M., Favo, C.M., Frecka, T.J., & Owens, C.L. (2009). Trends in the international fight against bribery and corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 199–244.

- Ministry of Communication and Information of the Republic of Indonesia. (2016). Blueprint (Blueptint) E-government application system for local government institutions. In Depkominfo. Depkominfo.

- Central Java Diskominfo. (2019). SPBE Evaluation. Central java the only provincial government with very good predicate. Central Java.Go.Id.

- Evans, D., & Yen, D.C. (2006). E-Government: Evolving relationship of citizens and government, domestic, and international development. Government Information Quarterly, 23(2), 207–235.

- Hadinagoro, S.S. (2020). Reducing sectoral ego and strengthening synergies for national productivity. National Library of the Republic of Indonesia.

- Hardjapamekas, E.R. (2017). Challenges of governance/governance in resolving the problem of corruption in the public & private sector. In Scientific Oration, Faculty of Administrative Sciences UI.

- Hariyanto, I. (2020). KPK: Indonesia's corruption perception index 40. Lost to Malaysia-Singapore. Detik.Com.

- Jateng, H. (2019). This is the secret of reward for making Central Java the most anti-corruption province. Central Java Province News Portal.

- Inspectorate of Central Java Province. (2020). Central java is the general champion of the KPK anti-corruption award. Central Java.Go.Id.

- Jayani, D.H. (2020). Indonesia's Corruption Perception Ranks 4th in Southeast Asia.

- Ke, W., & Wei, K.K. (2004). Successful e-government in Singapore. Communications of the ACM, 47(6), 95–99.

- Kim, S., & Cho, K. (2005). Achieving administrative transparency through information systems: A case study in the Seoul metropolitan government. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3591, 113–123.

- Lupu, D., & Lazar, C.G. (2015). Influence of e-government on the Level of Corruption in some EU and Non-EU States. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20(15), 365–371.

- Ministry of Finance Singapore. (2013). E-Government in Singapore. In www.egov.gov.sg.

- Mistry, J.J., & Jalal, A. (2012). An empirical analysis of the relationship between e-government and corruption. The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research, 12, 145–176.

- Mulyono, A.J. (2020). 5 Central Java Regions with Most Corruption Cases. Tagar.Id.

- Neupane, A., Soar, J., Vaidya, K., & Yong, J. (2012). Role of public e-procurement technology to reduce corruption in government procurement. In International Public Procurement Conference.

- Ojha, A., Palvia, S., & Gupta, M.P. (2009). A model for impact of e-government on corruption: Exploring theoretical foundation. Critical Thinking in E-Governance, 289.

- Park, C.H., & Kim, K. (2019). E-government as an anti-corruption tool: Panel data analysis across countries. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 1–17.

- Paulus, M., & Kristoufek, L. (2015). Worldwide clustering of the corruption perception. Physica A: Statistical mechanics and its applications, 428, 351–358.

- Pratiwi, E., & Nurani, F. (2019). Blusukan Forms of Democratic Leadership (Study on Jokowi's Leadership Era). In AP FIA UB (1–12). Universitas Brawijaya.

- Rizki, M.J. (2021). Seeing the effect of a decline in the corruption perception index on investor confidence.

- Saha, P., Nath, A., & Salehi-Sangari, E. (2010). Success of government e-service delivery: Does satisfaction matter? 9th IFIP WG 8.5 International Conference on Electronic Government (EGOV), 204–215.

- Schwester, R. (2009). Examining the barriers to e-government adoption. Electronic Journal of E-Government, 7(1), 113–122.

- Christan, R.A., & Setyaningrum, D. (2019). E-government and corruption perception index : A cross-country study. Jurnal Akuntansi AKUNES, 23(1), 11–20.

- Christan, R.A., & Setyaningrum, D. (2019). E-government and corruption perception index : A cross-country study. Jurnal Akuntansi AKUNES, 23(1), 11–20.

- Sheryazdanova, G., & Butterfield, J. (2017). E-government as an anti-corruption strategy in Kazakhstan. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 14(1), 83–94.

- Simarmata, M.H. (2017). The role of e-government and social media to create a culture of transparency and eradication of corruption. Integration, 3(2), 203–229.

- Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Gift giving, bribery and corruption: Ethical management of business relationships in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(2), 121–132.

- Suyatmiko, W., & Nicola, A. (2021). Corruption perceptions index 2020: Corruption, Covid-19 response and democracy's setback. Transparency International Indonesia.

- Tapsell, R. (2015). Indonesia’s Media Oligarchy and the “Jokowi Phenomenin.” Indonesia, 99, 29–50.

- Tenola, D. (2019). Corruption in Central Java Number 2 ICW Version. Ganjar: Very Bad. Jawa Pos.

- Urueña, R. (2018). Activism through Numbers? The corruption perception index and the use of indicators by civil society organisations. The Palgrave Handbook of Indicators in Global Governance, 371–387.

- Winata, D.K. (2020). KPK Reveals Six Corruption-Prone Areas. Media Indonesia.

- Yunita, N.P., & Aprianto, R.D. (2018). The current condition of the development of E-Government implementation in Indonesia: Website Analysis. National seminar on information and communication technology, 2018(Sentika), 329–336.