Research Article: 2018 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

Exploring the Social Entrepreneurial Intentions of Senior High School and College Students in a Philippine University: A PLS-SEM Approach

Patrick Adriel H Aure, De La Salle University

Abstract

This research explored the social entrepreneurial intentions (SEI) of senior high school and early college students through partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLSSEM). Anchored on the studies of Hockerts (2017) and Mair and Noboa (2006), this research extended their SEI conceptual model by examining grit (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews & Kelly, 2007), agreeableness (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas, 2006), and prior exposure to social action programs as antecedents that are hypothesized to be mediated by empathy, moral obligation, social entrepreneurial self-efficacy and perceived social support. Findings showed that for all respondents, the relationship of SEI with agreeableness are mediated by empathy, self-efficacy and perceived social support. Self-efficacy and social support mediated grit and SEI. To determine the difference between the drivers of SEI among senior high school and early college students, multigroup analysis was conducted. This study is relevant for proposing policies, regulations, and interventions that specifically target nascent social entrepreneurs at the early stages of their student lives.

Keywords

Social Entrepreneurial Intentions, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling, Grit, Agreeableness

Introduction

Over the years, social entrepreneurship has continued to garner attention in scholarship and practice. Although much has been written about how organizations and entrepreneurs can utilize business practices to solve society’s problems (Dees, 2012; Mair, Robinson & Hockerts, 2006), conceptualizations and definitions of the term still vary. Dees (2001) has been cited among various authors as one of the pioneers of social entrepreneurship as a field of study. He characterized social entrepreneurs as pursuing social value instead of focusing on commercial value, harnessing opportunities that serve mission and advocacies, engaging in innovation, acting bold despite limited sources, and shows accountability to the stakeholders and beneficiaries served for the initiatives pursued. Although social entrepreneurs are becoming recognized across the global, regional, and national levels, there is still much to be done to increase these changemakers. In a special report released by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Bosma, Schott, Terjesen & Kew, 2015), social entrepreneurs who are involved in starting up their social enterprises is 3.2% among 58 GEM economies, while commercial entrepreneurial activity averages around 7.6% globally. Current social entrepreneurs who are already leading and operating their own social entrepreneurial initiatives are around 3.7%. Most of the social entrepreneurial activities are associated with the young demographic, specifically 18-to-34-year-olds. Despite the visibility and recognition of social entrepreneurship at the global scale, there is still much to be done to increase the number social entrepreneurs across different countries. Given the role of social entrepreneurs in solving various problems, it is important to study what factors drive a person’s intention to engage in social entrepreneurial activities. The studies of Ayob, Yap, Sapuan & Rashid (2013), Chipeta and Surujlal (2016), Hockerts (2017), Politis, Ketikidis & Diamantidis (2016) and Prieto (2011), targeted undergraduate or postgraduate students, given that these respondents are more predisposed to think about their careers after education. In effect, most of these papers’ recommendations for policies are catered to students who are more career-oriented already.

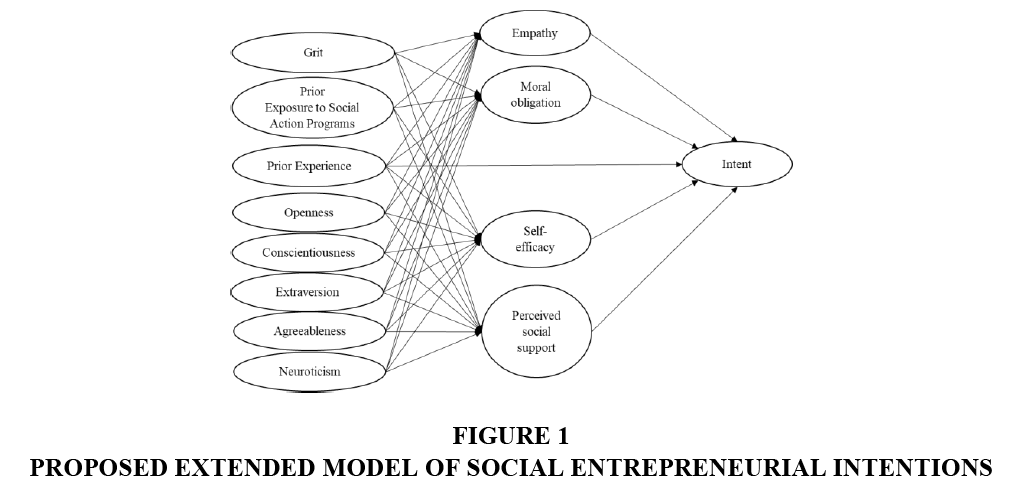

One of the objectives of this paper is to test the SEI model of Hockerts (2017), which was grounded on the ideas of Mair and Noboa (2006) and the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). The first research question is: What is the significance and extent of effect of the predictors-prior experience, empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and perceived social support-on SEI? Another objective of the paper is to explore what variables can extend the SEI model. Certain dimensions of personality represented by the Big Five model, such as openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism are posited to have an influence on social entrepreneurial intentions (?rengün & Ar?kbo?a, 2015; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010). Moreover, Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews & Kelly (2007), mentioned that grit is associated with personality traits. Specifically, their study found a correlation between grit and conscientiousness. Given the other studies’ findings that conscientiousness could have an influence on intention, it is interesting to explore whether grit also has an effect on SEI. Exploring these extensions of the SEI model is suitable for PLS-SEM (Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2014; Lowry & Gaskin, 2014). Furthermore, another variable that this paper examined is a student’s prior exposure to social action programs such as school-driven outreach initiatives. As theorized by Ajzen, these variables can be considered as background factors or antecedents that are mediated by the main predictors of intention. Therefore, the second research question is: What is the significance and extent of effect of agreeableness, grit, and prior exposure to social action programs on SEI, as mediated by empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and perceived social support?

Framework

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is the theoretical foundation for understanding intentions (Ajzen, 1991 & 2015; Miles, 2012). The theory surmises that an individual’s intentions best explain and predict one’s behaviour, with the following assumptions: (1) people behave in a systematic and rational manner; (2) actions are steered by conscious motives; and (3) individuals contemplate on the possible repercussions of actions before deciding to act. The TPB has been refined in various ways within the context of entrepreneurship (Kautonen, van-Gelderen & Fink, 2015; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Miles, 2012; Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014), as well as social entrepreneurial intentions (Ayob, Yap, Sapuan & Rashid, 2013; Bacq, Hartog & Hoogendoorn, 2016; Cavazos-Arroyo, Puente-Diaz & Agarwal, 2016; Chipeta & Surujlal, 2016; Forster & Grichnik, 2013; Griffiths, Gundry & Kickul, 2013; Hockerts, 2015 & 2017; Mair & Noboa, 2006; Politis, Ketikidis & Diamantidis, 2016; Prieto, Phipps & Friedrich, 2012; Rantanen & Toikko, 2013; Smith & Woodworth, 2012; Tiwari, Bhat & Tikoria, 2017; Urban & Teise, 2015; Yiu, Wan, Ng, Chen & Su, 2014; Zeng, Zheng & Lee, 2015). Mair and Noboa identified (1) empathy as a proxy for attitudes towards behaviour, (2) moral judgement as a proxy for social norms, (3) self-efficacy as a proxy for internal behavioural control, and (4) perceived presence of social support as a proxy for external behavioural control. Various researchers have also determined that personality, especially the Big Five dimensions (Baldasaro, Shanahan & Bauer, 2013; Cooper, Smillie & Corr, 2010; Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas, 2006; Goldberg, 1992), have an effect on commercial and social entrepreneurial intentions (Chlosta, Patzelt, Klein & Dormann, 2012; ?rengün & Ar?kbo?a, 2015; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Prieto, 2011; Wood, 2012). For this study, the Big Five dimensions were used as possible background factors that could influence SEI. In addition, grit was added as possible background characteristic that could have an influence on intention as well. However, instead of directly linking these variables with intention, this study followed the theory espoused by Ajzen (1991 & 2015), wherein background factors are considered as antecedents. As such, these background factors are mediated by the main TPB predictors in terms of their relationship with intention. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework that this particular study tried to test through structural equation modelling. Following the model advanced by Ajzen (1991 & 2015), grit, prior experience, prior exposure to social action programs, and the five personality traits were considered as background factors. Empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and perceived social support, which were posited by Hockerts (2017) and Mair and Noboa (2006) as proxies for TPB predictors, were considered the main influencers of SEI. All indicators were considered reflective, and they were derived based on existing scales (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas, 2006; Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews & Kelly, 2007; Hockerts, 2015).

Hypotheses

Hockerts found out that prior experience has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent. Furthermore, Hockerts also examined that the relationship between prior experience and social entrepreneurial intentions can be mediated by empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy and perceived social support.

H1-1a Prior experience has a direct positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H1-1b Prior experience, mediated by empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy and social support, has significant positive indirect influence on intention.

The theory of Mair and Noboa, as tested by Hockerts, posited that empathy, defined as an emotional response of concern and concern caused by seeing someone else in need, has a positive relationship with social entrepreneurial intentions. Moral obligation (characterized by the perception that societal norms imply a responsibility to help marginalized people), self-efficacy (person’s belief that individuals can contribute towards solving societal problems), and social support (perceived support an individual expects to receive from her or his surrounding) were also posited to positively influence intention.

H1-2 Empathy has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H1-3 Moral obligation has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H1-4 Self-efficacy has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H1-5 Perceived social support has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

The findings of various authors showed that among the Big Five personality traits, agreeableness has the strongest statistically significant relationship with intentions. However, when agreeableness and the aforementioned predictors are regressed using a forced-entry model, agreeableness lost its predictive power. Moreover, Ajzen (1991 & 2015) suggested that in accordance with TPB, personality and a person’s characteristics should be considered as background factors mediated by TPB variables.

H2 The big five personality traits, mediated by empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and social support, have significant positive indirect influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

Personality, which can be represented by the psychometrically validated Big Five model, are hypothesized by various authors to have an influence on social entrepreneurial intentions (?rengün & Ar?kbo?a, 2015; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010). In addition, Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews & Kelly, (2007) mentioned that grit is associated with personality traits, especially conscientiousness, although psychometric tests revealed that grit measures a different characteristic compared to the Big Five personality traits. Therefore, it is interesting to explore whether grit also has an effect on SEI.

H3 Grit, mediated by empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and social support, has a significant positive indirect influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

In addition, this particular study posited that similar to prior experience in terms of involvement with social organizations and solving social problems, a students’ exposure to social action programs may have an indirect effect on one’s social entrepreneurial intention. The researchers decided to keep the element of prior exposure to social action program different from the construct of prior experience to preserve the scales advocated by Hockerts (2017). Moreover, this construct is more context-specific to students in the Philippine university studied in this paper due to the abundance of outreach and social action programs they can choose to participate in.

H4-1 Prior exposure to social action programs, mediated by empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and social support, has a significant positive indirect influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H4-2 Prior exposure to social action programs, mediated by moral obligation, has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H4-3 Prior exposure to social action programs, mediated by self-efficacy, has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

H4-4 Prior exposure to social action programs, mediated by perceived social support, has a significant positive influence on social entrepreneurial intent.

Methodology

This study is set in a Philippine private business college, which is perceived as one of the best business schools in the country and a signatory of the Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME) advocated by the United Nations. The university aims to develop future business leaders that can reconcile making profits with serving society, especially the poor and marginalized. The university is seen as a potential breeding ground of future social entrepreneurs and is ripe for a study exploring what drives its business students’ social entrepreneurial intentions. The research design primarily used the survey method, featuring established questions from various authors (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas, 2006; Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews & Kelly, 2007; Hockerts, 2017). The Likert scales used ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except for the question on prior exposure to social action programs, which was measured in a binary manner (0 for no, 1 for yes). As a tool for analysis, partial least squares structural equation modeling was employed as recommended by Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt (2014) and Lowry and Gaskin (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) is recommended when the data does not follow a normal distribution and when the relationships contain multiple mediating relationships (Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2014; Lowry & Gaskin, 2014). The sample size was computed based on the recommendations of Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, (2014). With the maximum number of arrows pointing at a construct (in this case, the posited mediating variables) equaling to 8, setting the significance level to 0.05, a statistical power of 80%, and minimum R2 of 0.25, the recommended minimum sample size is 84. This study was able to gather data from 270 respondents, which is above the recommended minimum. Furthermore, there were 153 college students and 117 senior high school students that responded. Thus, both groups have sufficient sample size suitable for multigroup analysis. The data was gathered through Google Forms. This research utilized purposive sampling, targeting senior high school and undergraduate business students of a private business school. Senior high school and undergraduate students are one of the most important stakeholders in terms of understanding predisposition to social entrepreneurial initiatives, given how educators and policy-makers can design programs for their learning-showing how understanding their intentions are critical for unearthing insights (Ayob, Yap, Sapuan & Rashid, 2013; Chipeta & Surujlal, 2016; ?rengün & Ar?kbo?a, 2015; Prieto, 2011; Tiwari, Bhat & Tikoria, 2017).

To perform PLS-SEM, the SmartPLS 3.0 (Ringle, Wende & Becker, 2015) software was utilized. All latent variables were considered to have reflective indicators. Factor analyses, tests of construct validity and reliability, tests for discriminant validity, tests for multicollinearity, and model fit were all performed in SmartPLS 3.0, as guided by Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, (2014) and Lowry and Gaskin (2014). The usual PLS algorithm method and bootstrapping (J = 10,000) were employed as suggested by Ringle, Wende & Becker, (2015). As recommended by Kock (2014), this study utilized one-tailed p-value tests of significance since the a priori hypotheses inferred on the direction and signs of the variables relationships, which is backed by prior research.

Discussion of Results

This study was able to gather data from 270 respondents. There were 153 college students and 117 senior high school students that responded. The variables were measured through indicators established by various researchers. The personality questions were lifted from the Mini-IPIP (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas, 2006). Grit questions came from the scale created by Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews & Kelly, (2007). Scales about the prior experience, empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, and social support were sourced from the study of Hockerts (2017). The question on prior exposure to social action program was asked as a Yes/No question. Statistical tests were used to assess the construct reliability and validity of the variables in the model. The values indicated acceptable levels of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability which is a > 0.60 (Lowry & Gaskin, 2014), except for conscientiousness, which had a poor rating for Cronbach’s Alpha. To remedy this, future research should explore including more questions about conscientiousness and personality traits in general to increase validity; although for conscientiousness, its composite reliability is acceptable. On the other hand, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was acceptable since no value was below 0.50.

To assess discriminant validity, cross-loadings of the questions were examined through factor analysis conducted in PLS-SEM. Indicators or questions pertaining to grit and agreeableness were removed until cross-loadings were deemed acceptable. Lowry and Gaskin (2014) proposed that the difference between the main values and cross-loaded values should not exceed 0.20. The final cross-loadings matrix showed that there are no significant cross-loadings of the indicators on other latent variables. To test for multicollinearity, it is essential to look at variance inflation factors of the indicators (VIF). All VIFs were less than 10.00 (or conservatively, less than 4.00), hence there was no significant multicollinearity among the indicators. To further assess discriminant validity, it is also important to satisfy the Fornell-Larcker criterion, wherein the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each latent variable should be higher than their respective correlation coefficients with other latent variables. The Fornell-Larcker criterion was satisfied by the model. Since the tests for reliability, validity, and multicollinearity were satisfied, the structural model and its paths can be analysed with greater confidence. The following Table 1 features path estimates and p-values, which was the result of the PLS algorithm and bootstrapping (J=10,000) procedure performed through SmartPLS 3.0, as recommended by Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, (2014) and Lowry and Gaskin (2014).

| Table 1 Results Of The Pls Algorithm Bootstrapping And Multigroup Analysis |

||||||

| Paths | Path Estimates (All) | p-Values (All) | Path Estimates (College) | p-Values (College) | Path Estimates (Senior High) | p-Values (Senior High) |

| Agreeableness->Empathy | 0.485 | 0.000* | 0.527 | 0.000* | 0.482 | 0.000* |

| Agreeableness->Moral Obligation | 0.281 | 0.000* | 0.255 | 0.001* | 0.343 | 0.000* |

| Agreeableness->Self-Efficacy | 0.328 | 0.000* | 0.356 | 0.000* | 0.379 | 0.000* |

| Agreeableness->Social Support | 0.257 | 0.000* | 0.300 | 0.000* | 0.304 | 0.002* |

| Conscientiousness->Empathy | -0.046 | 0.318 | 0.039 | 0.376 | -0.003 | 0.488 |

| Conscientiousness-> Moral Obligation |

-0.050 | 0.277 | 0.038 | 0.389 | -0.053 | 0.286 |

| Conscientiousness->Self-Efficacy | 0.004 | 0.475 | -0.083 | 0.215 | 0.148 | 0.046* |

| Conscientiousness->Social Support | -0.073 | 0.159 | -0.088 | 0.376 | -0.079 | 0.488 |

| Empathy->Intent | 0.188 | 0.003* | 0.005 | 0.477 | 0.391 | 0.000* |

| Extraversion->Empathy | -0.015 | 0.406 | 0.049 | 0.270 | -0.052 | 0.295 |

| Extraversion->Moral Obligation | 0.017 | 0.398 | 0.063 | 0.229 | -0.019 | 0.424 |

| Extraversion->Self-Efficacy | 0.039 | 0.251 | 0.018 | 0.400 | 0.078 | 0.169 |

| Extraversion->Social Support | 0.109 | 0.030* | 0.074 | 0.154 | 0.198 | 0.017* |

| Grit->Empathy | 0.074 | 0.137 | 0.060 | 0.225 | -0.004 | 0.483 |

| Grit->Moral Obligation | 0.244 | 0.001* | 0.270 | 0.001* | 0.278 | 0.001* |

| Grit->Self-Efficacy | 0.229 | 0.000* | 0.287 | 0.000* | 0.265 | 0.002* |

| Grit->Social Support | 0.187 | 0.002* | 0.225 | 0.000* | 0.142 | 0.074 |

| Moral Obligation->Intent | 0.002 | 0.491 | -0.009 | 0.466 | -0.069 | 0.281 |

| Neuroticism->Empathy | 0.168 | 0.003* | 0.088 | 0.185 | 0.257 | 0.001* |

| Neuroticism->Moral Obligation | 0.005 | 0.470 | -0.037 | 0.357 | 0.011 | 0.453 |

| Neuroticism->Self-Efficacy | 0.007 | 0.452 | 0.005 | 0.479 | 0.003 | 0.487 |

| Neuroticism->Social Support | 0.009 | 0.438 | 0.013 | 0.452 | -0.007 | 0.472 |

| Openness->Empathy | 0.010 | 0.439 | -0.032 | 0.365 | 0.039 | 0.329 |

| Openness->Moral Obligation | 0.072 | 0.122 | 0.018 | 0.420 | 0.213 | 0.009* |

| Openness->Self-Efficacy | 0.116 | 0.028* | -0.020 | 0.405 | 0.321 | 0.000* |

| Openness->Social Support | 0.128 | 0.018* | 0.126 | 0.092 | 0.227 | 0.007* |

| Prior Exp->Empathy | 0.143 | 0.010* | 0.125 | 0.067 | 0.235 | 0.003* |

| Prior Exp->Intent | 0.191 | 0.000* | 0.227 | 0.000* | 0.148 | 0.016* |

| Prior Exp->Moral Obligation | 0.081 | 0.144 | 0.120 | 0.119 | 0.027 | 0.393 |

| Prior Exp->Self-Efficacy | 0.035 | 0.300 | 0.164 | 0.023* | -0.139 | 0.071 |

| Prior Exp->Social Support | 0.120 | 0.039* | 0.245 | 0.001* | 0.013 | 0.459 |

| Prior SAP->Empathy | 0.055 | 0.146 | -0.006 | 0.468 | 0.146 | 0.034* |

| Prior SAP->Moral Obligation | 0.016 | 0.384 | -0.064 | 0.176 | 0.143 | 0.046* |

| Prior SAP->Self-Efficacy | 0.037 | 0.246 | -0.039 | 0.281 | 0.154 | 0.033* |

| Prior SAP->Social Support | 0.003 | 0.482 | -0.043 | 0.256 | 0.070 | 0.222 |

| Self-Efficacy->Intent | 0.388 | 0.000* | 0.418 | 0.000* | 0.413 | 0.000* |

| Social Support->Intent | 0.127 | 0.024* | 0.198 | 0.011* | 0.117 | 0.097 |

The first set of hypotheses (H1) tested the findings of Hockerts (2017) anchored on the proposed model of Mair and Noboa (2006). The results of the path analysis revealed that prior experience has a statistically significant positive influence on empathy, social support, and intention. Empathy, self-efficacy and perceived social support have a statistically significant positive influence on intentions, as expected. However, moral obligation did not predict intention. In this case, only empathy and social support partially mediated the relationship between prior experience and intention. As such, the results of the PLS algorithm and bootstrapping only partially validated the findings of Hockerts. The second set of hypotheses (H2) tested the relationship of personality with empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, social support, and intention. The results of the tests revealed that agreeableness positively influenced all the aforementioned predictors. A look at the total indirect effect of agreeableness on intention revealed a statistically significant relationship (b=0.268, p<0.001). In terms of the specific indirect effects, self-efficacy (b=0.138, p<0.001), self-efficacy (b=0.138, p<0.001) and social support (b=0.037, p=0.034) fully mediated the relationship between agreeableness and intention. Furthermore, extraversion positively influenced social support, but the total effects indicated that social support did not facilitate mediation between extraversion and intent (p=0.221). Neuroticism positively influenced empathy, although no mediation happened in terms of neuroticism’s total effect on intent (p=0.163). Openness positively influenced self-efficacy (specific indirect effect to intention: b=0.045, p=0.045) and social support (specific indirect effect to intention: b=0.016, p=0.086), and the total effects suggested that these two variables mediated openness and intent (p=0.042). The third set of hypotheses (H3) tested the relationship of grit with empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, social support and intention. The results of the tests revealed that grit positively influenced moral obligation, self-efficacy, and social support with statistical significance. A look at the total indirect effect of grit on intention revealed a statistically significant relationship (b=0.132, p<0.001). In terms of specific indirect effects, self-efficacy (b=0.138, p<0.001) fully mediated the relationship between grit and intention. In addition, social support functions as a full mediator but only with a marginal statistical significance (b=0.026, p=0.061). The final set of hypotheses (H4) tested the relationship of prior exposure to social action programs with empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy, social support and intention. The results of the tests revealed that prior exposure to social action programs only affected empathy at a marginal statistical significance (b=0.075, p=0.074). Therefore, general to all respondents, prior exposure to social action programs were not mediated by the predictors with regards to its relationship with intention. The r-squared values of the model showed that the other latent variables explained 45.4% of the variance in social entrepreneurial intentions, which is acceptable in field of social science (Lowry & Gaskin, 2014).

Multigroup analysis (MGA) was conducted through SmartPLS. The MGA validated that for both groups, agreeableness positively influenced empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy and social support. Grit positively influenced moral obligation, self-efficacy and social support. Prior experience positively influenced empathy and intent. Self-efficacy and social support positively influenced intent. For the early college group, prior experience positively influenced social support. Social support also positively influenced intent-therefore, social support mediated partially mediated the relationship between prior experience and intention. On the other hand, for the senior high school group, empathy positively influenced intent. Prior exposure to social action programs positively influenced empathy, moral obligation and self-efficacy. Therefore, for senior high school students, empathy and self-efficacy fully mediated the relationship between prior exposure to social action programs and intention. Moreover, for the senior high school group, more personality dimensions influenced the TPB predictors. Openness influenced moral obligation, self-efficacy and social support. Extraversion influenced social support. Conscientiousness influenced self-efficacy. Neuroticism influenced empathy. As such, compared to the college group, personality played a bigger role in influencing SEI as background factors for the senior high school students.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

The results of the general PLS-SEM analysis and the multigroup analysis only partially validated the model of Hockerts. Overall, prior experience and self-efficacy were the best predictors of social entrepreneurial intention. The other variables in the model of Hockerts had various influences depending on the groups. Therefore, policy-makers should prioritize interventions and advocacy campaigns anchored on building the self-efficacies for both groups. These programs should be able to expose both groups to circumstances where they can solve social problems or be involved in managing social organizations. The succeeding research questions and hypotheses explored the role of grit and personality traits as background factors that affected intentions through mediators. For both groups, agreeableness positively influenced empathy, moral obligation, self-efficacy and social support. For the total effect for both groups, agreeableness influenced intention as mediated by self-efficacy. For college students, social support also mediated the relationship between grit and intention. Specifically, for senior high school students, empathy mediated the relationship between agreeableness and intention. In terms of grit, its relationship with intention is mediated by self-efficacy. Moreover, personality traits such as conscientiousness and openness played a bigger role in influencing the main SEI predictors for senior high school students. Overall, policy-makers should cultivate an environment that fosters grit and agreeable personality traits-these are two background factors that affect intention as shown by the two groups. However, the interventions must be tailor fit to the groups. For example, early college student policies should encourage group learning given the significance of perceived social support; while for senior high school students, further exposure to social action, problems, and organizations can heighten empathy, which then influences intention. Generally, policy-makers and academic institutions can design development programs that expose students to managing and jumpstarting social enterprises side-by-side with mentorship, group learning and learn-by-doing mechanisms. Other background factors may be explored to have a better appreciation of the model.

References

- Ajzen, I. (2015). Consumer attitudes and behaviour: The theory of planned behaviour applied to food consumption decisions. Rivivista Di Economia Agraria, 2(70), 121-138.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Ayob, N., Yap, C.S., Sapuan, D.A. & Rashid, M.Z.A. (2013). Social entrepreneurial intention among business undergraduates: An emerging economy perspective. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 15(3), 249-267.

- Bacq, S., Hartog, C. & Hoogendoorn, B. (2016). Beyond the moral portrayal of social entrepreneurs: An empirical approach to who they are and what drives them. Journal of Business Ethics, 133, 703-718.

- Baldasaro, R.E., Shanahan, M.J. & Bauer, D.J. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Mini-IPIP in a large, nationally representative sample of young adults. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(1), 74-84.

- Bosma, N., Schott, T., Terjesen, S. & Kew, P. (2015). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Special topic report on social entrepreneurship. GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2786949

- Cavazos-Arroyo, J., Puente-Diaz, R. & Agarwal, N. (2016). An examination of certain antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions among Mexico residents. Review of Business Management, 19(64), 180-199.

- Chipeta, E.M. & Surujlal, J. (2016). Influence of gender and age on social entrepreneurship intentions among university students in Gauteng province, South Africa. Gender & Behaviour, 14(1), 6885-6899.

- Chlosta, S., Patzelt, H., Klein, S.B. & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 121-138.

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S.G. & Aiken, L.S. (2003). Applied multiple regression and correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (Third Edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Cooper, A.J., Smillie, L.D. & Corr, P.J. (2010). A confirmatory factor analysis of the Mini-IPIP five-factor model personality scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 688-691.

- Dees, J.G. (2001). The meaning of social entrepreneurship. Retrieved from https://entrepreneurship.duke.edu/news-item/the-meaning-of-social-entrepreneurship/

- Dees, J.G. (2012). A tale of two cultures: Charity, problem solving and the future of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 321-334.

- Donnellan, M.B., Oswald, F.L., Baird, B.M. & Lucas, R.E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192-203.

- Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D. & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087-1101.

- Forster, F. & Grichnik, D. (2013). Social entrepreneurial intention formation of corporate volunteers. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 153-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2013.777358

- Goldberg, L.R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 26-42.

- Griffiths, M.D., Gundry, L.K. & Kickul, J.R. (2013). The socio-political, economic and cultural determinants of social entrepreneurship activity: An empirical examination. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(2), 341-357.

- Hair, J.F.J., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C. & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Thousand oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Hockerts, K. (2015). The social entrepreneurial antecedents scale (SEAS): A validation study. Social Enterprise Journal, 11(3), 260-280.

- Hockerts, K. (2017). Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 105-130.

- ?rengün, O. & Ar?kbo?a, ?. (2015). The effect of personality traits on social entrepreneurship intentions: A field research. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 195, 1186-1195.

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M. & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behaviour in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655-674.

- Kickul, J. & Lyons, T.S. (2012). Understanding social entrepreneurship: The relentless pursuit of mission in an ever changing world, 21.

- Kock, N. (2014). One-tailed or two-tailed P values in PLS-SEM. Laredo, Texas: Script Warp Systems.

- Liñán, F. & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11, 907-933.

- Lowry, P.B. & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modelling (SEM) for building and testing behavioural causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(2), 123-146.

- Mair, J. & Noboa, E. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In J. Mair, J. Robinson. & Hockerts, K. (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship (pp. 121-135). United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230625655

- Mair, J., Robinson, J. & Hockerts, K. (2006). Social entrepreneurship. In J. Mair, J. Robinson & K. Hockerts, (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Miles, J.A. (2012). Management and Organization Theory (First Edition). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Nga, J.K.H. & Shamuganathan, G. (2010). The influence of personality traits and demographic factors on social entrepreneurship starts up intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 259-282.

- Politis, K., Ketikidis, P. & Diamantidis, A.D. (2016). An investigation of social entrepreneurial intentions formation among South-East European postgraduate students. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(4), 1120-1141.

- Prieto, L.C. (2011). The influence of proactive personality on social entrepreneurial intentions among African-American and Hispanic undergraduate students: The moderating role of hope. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 17(2), 77-97.

- Prieto, L.C., Phipps, S.T.A. & Friedrich, T.L. (2012). Social entrepreneur development: An integration of critical pedagogy, the theory of planned behaviour and the ACS model. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 18(2), 1-16.

- Rantanen, T. & Toikko, T. (2013). Social values, societal entrepreneurship attitudes and entrepreneurial intention of young people in the Finnish welfare state. Poznan University of Economics Review, 13(1), 7-25.

- Ringle, C., Wende, S. & Becker, J.M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Retrieved from http://www.smartpls.com

- Schlaegel, C. & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291-332.

- Smith, I.H. & Woodworth, W.P. (2012). Developing social entrepreneurs and social innovators: A social identity and self-efficacy approach. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 11(3), 390-407.

- Tiwari, P., Bhat, A.K. & Tikoria, J. (2017). An empirical analysis of the factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 7(1), 9.

- Urban, B. & Teise, H. (2015). Antecedents to social entrepreneurship intentions?: An empirical study in South Africa. Management Dynamics, 24(2), 36-53.

- Wood, S. (2012). Prone to progress: Using personality to identify supporters of innovative social entrepreneurship. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(1), 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.11.060

- Yiu, D.W., Wan, W.P., Ng, F.W., Chen, X. & Su, J. (2014). Sentimental drivers of social entrepreneurship: A study of China’s Guangcai (Glorious) program. Management and Organization Review, 10(1), 55-80.

- Zeng, F.Q., Zheng, M.Q. & Lee, D. (2015). An empirical study on the influencing factors of university students’ entrepreneurial intention-A research based on the Chinese nascent social entrepreneur. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 11(1), 89-126.