Research Article: 2020 Vol: 19 Issue: 4

External Factors and Risk Considerations: Applying the Institutional-Based View of Management

Mark William Cawman, Azusa Pacific University

David Ming Liu, Southwest Baptist University

Abstract

This research builds on the Institution-based view of strategic management. It introduces an expansion of the PEST model to the PESTLEEG Analysis Model for analysis with a Failure Mode/Effects Analysis (FMEA). This is to provide a ranking methodology for evaluating both domestic and international target environments. This is especially pertinent to small/mid-size businesses, expanding or transitioning industry (e.g., manufacturing or similar) into new environments. This study has both academic (Strategic Management and International Business) and industry significance with timely application in the current globalization and political environments. Opportunities exist for further research, both horizontally (e.g., extensions, industries, and PESTLEEG factor applications) and vertically (e.g., proof through case studies) due to the recent formalizing of the Institution-based view theory and the PESTLEEG analysis model’s use with a FMEA application process.

Keywords

Institution-Based View, Industry-Based View, Resource-Based View, Strategic Management, PEST, PESTLE, PESTLEEG, Emerging Markets, FMEA, International Business, Strategic Planning.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, industry has become increasingly globalized, and the academic disciplines of Strategic Management and International Business are thus increasingly intertwined. Traditional management theories have been served or adapted/modified to fit the globalization of business, but the dynamic nature of international markets, relationships, economies, etc., require further tools to be successful in effective global strategy. Especially pertinent to small/mid-size businesses, expanding or transitioning industry (e.g., manufacturing or similar) into new environments requires considerable strategic planning and risk considerations. The Institution-Based View of strategic management was developed from observed gaps in the Resource and Industry-Based Views. Focus on the firm’s abilities (resource-based view) or the overall market opportunities (industry-based view) in strategic planning do not account for many implications that affect successful implementation/realization of strategic plans. This research builds on the institution-based view of strategic management and introduces an expansion of the PEST model to the PESTLEEG Analysis Model for analysis with the Failure Mode/Effects Analysis (FMEA) to provide a ranking methodology for evaluating both domestic and international target environments. The objective of this research is to provide a methodology for practitioners to give weighted consideration to the various external (institutional) factors for risk considerations and decisions in strategic planning. Opportunities exist for further research, both horizontally (e.g., extensions, industries, and PESTLEEG factor applications) and vertically (e.g., proof through case studies) due to the recent formalizing of the Institution-based view theory and the PESTLEEG analysis model’s use with an FMEA. This study has both academic and industry significance with timely application in the current globalization and political environments.

Definition/Construction of Strategic Management Constructs

Strategic management

The study of strategic management includes three areas of emphasis, namely: definition, construction, and application. Some scholars attempt to define (e.g., definition) what strategic management is and/or is not (Evered, 1983; Oliver, 2001). Other researchers analyze the methods and components required in the development (e.g., construction) of strategy and its history (Foo, 2007; Rumelt, 2011). The final and hermeneutical emphasis of study is in application and execution of strategy (Kaplan & Norton, 2008; Ross et al., 2006). This study combines the definition and construction with comprehensive and holistic analysis of business environment factors in the institution-based view of strategic management, and then focuses on application(s) of our proposed PESTLEEG factors framework, analyzed via a Failure Mode/Effects Analysis (FMEA) application. This is designed to give small/mid-size businesses some examples and tools for strategic planning and risk considerations, and to academically extend this research to strategic management and international business.

David (2013) defines “strategic management” as “the art and science of formulating, implementing, and evaluating cross-functional decisions that enables an organization to achieve its objectives” (David, 2013). Also describes strategic management as a cyclical process of Formation, Implementation, and Evaluation (FIE), later expanded by David Liu to (FIVE) Formation, Implementation, Validation, and Evaluation (Liu, 2014). Mintzberg et al. (1998) defined strategy as “a pattern, that is, consistency in behavior over time”. Mintzberg went on to describe five definitions (“five Ps for strategy”) of strategy: strategy as a plan, strategy as a pattern, strategy as position, strategy as ploy, and strategy as perspective. Kvint (2009) suggests that strategy is “a system of finding, formulating, and developing a doctrine that will ensure long-term success if followed faithfully” (Keynote Definitions). Chandler (1962) defined strategy as “the determination of the basic long-term goals of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals”.

The academic study and interest in strategic planning applying to business management is relatively recent, and in his 1998 publication, Mintzberg suggests that academics had only studied strategy for about two decades (Mintzberg et al., 1998). Strategic management is demonstrated throughout history, through both study and practice in military and war environments long before it was formal in business. Several definitions of strategy or strategic management originate from the military involving preparation, planning, and coordination of resources. The term “strategic management” thus embodies planning, adopting courses of action, and allocating resources to accomplish the firm’s desired outcome. It is a cyclical process including evaluation and progress checks (outputs) back into the planning phase (inputs).

Industry-based view of strategic management

The Industry-based view suggests that conditions within an industry (e.g., market) wholly or largely determine strategy (Porter, 1979). Porter (1979) introduced the concept of the five strategic forces: rivalry among competitors, power of suppliers, power of customers, threat of new market entrants, and threat of substitute products or services. This was primarily an industry-based view that assumed a firm could/would respond to these forces with appropriate resources. Porter et al. (2008) appears to adapt to elements of the resource, industry, and institution tripod in his article The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy as he speaks to government (aligning with institutional-based view) and the firm’s key resources and processes (aligning with resource-based view).

Resource-based view of strategic management

The resource-based theory purports that firm-specific characteristics or differences determine and are the significant drivers or influencers of strategy (Penrose, 1959). Penrose’s (1959) research (resource-based view) suggested that strategic management is primarily a firm’s ability to organize and utilize their resources in an efficient and effective manner. Many criticisms of resource-based theory involve underdog scenarios, where deception, timing, and other competitive strategies, or relationships and other interactive strategies, trump the entity with superior resources. Tzu (2012) provides excellent illustrations (war-based with application to management) of how great strategy and relationship alignments can overcome a lack of resources. (West III & DeCastro (2001) argue that on occasion resources can prove a detriment if they are the wrong resources, or if utilizing the resources usurps attention in strategy and drives the wrong behaviors. Priem & Butler (2001), purport that the resource-based view assumes stability in markets and does not adequately rationalize the value of the resources to the business environment in strategic planning.

Institution-based view of strategic management

The institution-based view (Peng, 2002) of strategic management is both an attempt at an expansion of the definition of strategic management and an essential component in application or the actual strategic management process. Michael Peng defines “Institution” in Towards an Institutions-Based View of Business Strategy. In operationalizing the term, Peng cites North’s (1990) definition of institutions, as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (Peng, 2002). Peng also quotes Scott’s (1995) definition of institutions as “cognitive, normative, and regulative structures and activities that provide stability and meaning to social behavior” (Scott, 1995 as cited by Peng, 2002). Peng then references Davis and North (1971) in defining an “institutional framework” as “the set of fundamental political, social, and legal ground rules that establishes the basis for production, exchange, and distribution” (Peng, 2002). Institution, as a construct, is well defined as governments, practices, or relationships (Keohane, 1989) and could be illustrated by the institution of marriage or government institutions.

In studying the institution-based view of strategic management, the term “institution” thus embodies the PEST (Aguilar, 1967) factors that are implications for production, exchange, and distribution beyond the environments of the firm and the industry (competitive environment). The institution-based view of strategy is especially relevant in emerging markets and international business, but also has applications in all strategic planning that aims to mitigate threats and take advantage of opportunities (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats or SWOT analysis) (Pickton & Wright, 1998). Peng (2002) recognizes resource and industry views, but introduces the institutional-based view, suggesting that understanding and planning a response to the PEST (Aguilar, 1967) environments is important to planning resources or understanding markets. This view can help firms and industries avoid some risks and capitalize on opportunities through adequate planning. Zaheer (1995) suggests that some firms have difficulty importing or exporting a specific successful practice or strength in international business, which suggests the resource-based view needs the institution-based view in accompaniment for success. Zaheer (1995) also purports that a firm can have a competitive advantage (industry-based view) if that firm is superior in understanding and mitigating cultural/ social implications (institutional-based view).

Institution-based strategic management builds on (or fills a gap left by) the industry-based and resource-based management theories, and includes focused attention on governmental, societal, cultural, and other external factors that could influence growth and/or location strategies (Peng, 2002). It is partially accurate to include the resource-based view and the industry-based view as predecessors of institutional-based view, but the three complete rather than evolve from each other (Peng et al., 2008). If emerging market opportunities are fraught with unfavorable Economic, Technical, Political and Social (ETPS/PEST) factors (Aguilar, 1967), it does not matter how efficient a firm is in organizing and utilizing resources (e.g., resource-based view), or how attractive a specific market or competitive landscape is (industry-based view). Peng et al. (2009) expand on the institution-based view of strategic management and suggest that the institution-based view is not a holistic view, but rather fills a gap in other theories. Their research refers to the resource-based view, industry-based view, and the institution-based view as a tripod for strategic management, especially required in emerging markets (Hoskisson et al., 2000).

Summarizing the Peng et al., (2009) tripod of the three theories (resource-based, industry-based, and institution-based), the literature supports the collaboration or amalgamation versus autonomy of these theories or superiority of one over the other. The literature on the application and extensions of the institution-based view of strategic management, considers the institution-based view in overall strategy (as the tripod rather than in isolation).

Application(s) and Extensions of the Institution-Based View of Management

Foreign applications

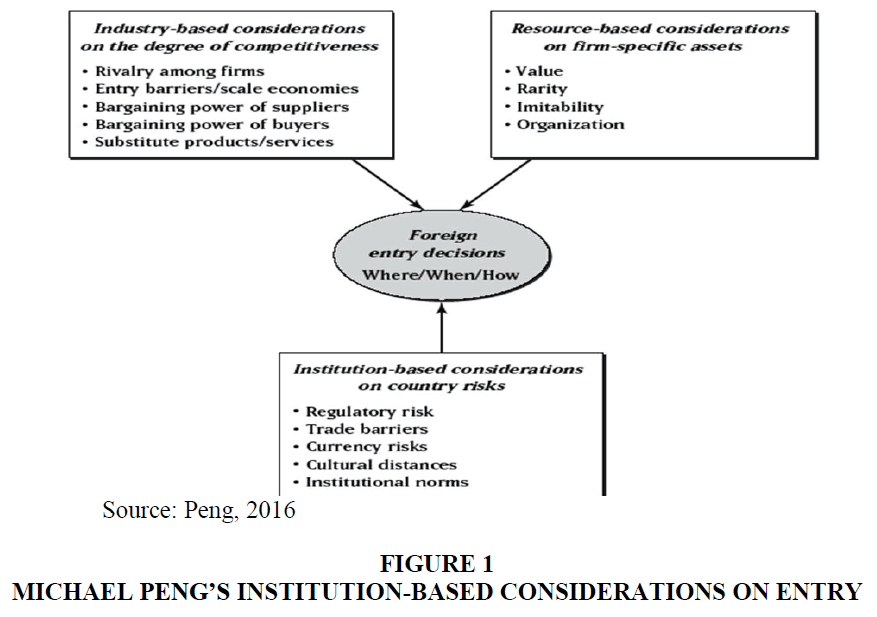

The considerations for entry/country risks have the potential to negate or enhance considerations of competitiveness (industry-based view) or firm-specific assets or strengths (resource-based view). All of the considerations are inputs to strategic planning, as consideration of a single risk could prohibit entry irrespective of competitiveness or resources (e.g., trade barriers, legal issues, or political unrest). Utilizing a framework to evaluate the country risks/ benefits is a valuable component of a thorough consideration of entry into a market, country, or culture. In Figure 1, Peng (2014) illustrates some of the considerations of the institutional-based view in entry decisions to foreign markets.

As frameworks to evaluate these external environmental factors, there are many variations of Aguilar’s (1967) ETPS analysis (Economic, Technical, Political and Social) which was reordered to the STEP and PEST order and most commonly known as the PEST Analysis Model. A few of these variants are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Acronyms and Models In External Factors – Variations of ETPS/Pest | |

| Acronyms | Constructs/Factors |

| PESTLE | Political, Economic, Sociological, Technological, Legal, Environmental |

| PESTEL | Political, Economic, Sociological, Technological, Environmental, Labor |

| PESTLIED | Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, International, Environmental, Demographic |

| STEEPLE | Social/Demographic, Technological, Economic, Environmental, Political, Legal, Ethical |

| SLEPT | Social, Legal, Economic, Political, Technological |

| STEPE | Social, Technical, Economic, Political, and Ecological |

This research recommends the expansion by Liu (2015) to the PESTLEEG Factors Analysis Model (Political, Economical, Social-Cultural, Technical, Legal, Ethical, Environmental, Geographical-Demographical) to best facilitate further rating and evaluation tools to support the Institutional-based view (Peng, 2002) of strategic management.

Organizations such as the United Nations (UN), the World Bank (WB), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are resources (although not the only source or a complete resource(s)) for other PESTLEEG considerations as illustrated in Table 2.

| Table 2 Organizations and Pestleeg Alignment in International Business | |

| Organization | PESTLEEG Factors |

| World Trade Organization (WTO) | Legal, Ethical |

| World Bank (WB) | Economical, Technological, & Environmental |

| International Monetary Fund (IMF) | Economical, Ethical |

| United Nations (UN) | Political |

Note. Adapted from PESTLEEG and descriptors found in respective organizations websites: (International Monetary Fund Website, 2019; United Nations Website, n.d.; World Bank Group Website, 2020; World Trade Organization Website, 2020)

To evaluate the social-cultural implications of market entry, a cultural distances assessment utilizing the Hofstede cultural tools (Hofstede, n.d.) assists in research or inputs to strategic planning (Hofstede et al., 2010). Institutional norms and other useful information available to travelers are appropriate for business planning inputs to entry considerations in foreign markets, and are available by utilizing these resources for this purpose. One example of a resource for cultural study is international etiquette guides (Kwintessential Website, 2013). Wickham (2014) suggest that language and cultural barriers exist even where there is bilingual capability. Wickham states that “it is safe to say that people are touched more deeply, on an emotional level, when they hear their native language-their “mother tongue” so to speak –spoken”. Wickham (2014) suggests getting at least a basic understanding of local language or dialects as part of business strategy, and taking time to learn the cultural dynamics. Richman (1965) researches to what extent American management principles and practices transfer to other countries effectively. Also he suggests further research is possible utilizing a variables model of cultural constraints (C), dynamic managerial problems (D), elements of the management process (P), and managerial effectiveness (E). He purports that it is required to study each situation (independent and dependent variables), as there is not a universal answer to American management transferability, and cultural differences exist and exacerbate certain management efforts in international business.

Entry decisions for foreign markets are only part of business strategy. Once a firm is engaged in global business, continued PESTLEEG factors are implications in business, and must be part of the ongoing strategic planning. A firm or industry cannot confuse cultural collaboration with hegemony. Lu et al. (2008) research suggests knowledge intensive societies do not want to continue to accept menial off-load productions long term, but seek legitimacy and desire to innovate and receive recognition for innovation. Effective application of institutional-based views of strategic management include considerations such as this social-cultural aspect, mitigating future issues and thereby increasing the firm’s resources (resource-based view) and assuring competitiveness by innovation and inclusion. Failure to embrace an emerging economy’s need for legitimacy can increase (using Porter’s five forces) the threat of substitute products and the threat of new entrants (Porter, 1979) due to migration or alienation of resources.

There are many implications in international business that the institution-based view brings to the ongoing strategic management process in sustaining business relationships (after the entry decision). Lee (2011) research suggests that the institution-based view of strategic management is valuable to understanding human resource management across borders. Human resource management across cultures presents challenges that would likely not be in strategic planning if the institution-based view is not included. Van Essen et al. (2012) address executive compensation, and suggest there is a social-cultural implication that strategic planning must consider through the institution-based view. Zhou & Peng (2010) research describes a short-term/ long-term progression in transactions, and suggests that through cultural understanding, the exchanges evolve towards more relational than arms-length. The evolution to more relational transactions involves building trust, involving social-cultural and ethical factors. The social aspects that are involved in transactions would not be considered in strategic planning if the institution-based view is not utilized. Knowledge of competitive advantage or environment (industry-based view) as inputs to strategic planning is also not complete without some institution-based studies. Gao et al. (2010) use the strategy tripod (resource, industry, and institution-based views) for perspective on export behaviors and other economical projections. Peng et al. (2008) suggest that only by adding institution-based theory to the resource and industry-based views, forming the tripod (resource, industry, and institution-based views), is anti-dumping (entry barrier) and governing corporations in emerging economies adequately addressed. Peng et al. (2008) specifically study entry to India and growth in China, and suggest that the inclusion of the institution-based view is significant in determining strategy and performance in international business. Ahn & York (2011) researched the emerging biotechnology industry in Malaysia and compared/contrasted the resource-based view and the institution-based view of strategic management. Also found that both the resource-based view and the institutional-based view were valuable and that it was important how some institutional intervention was used (e.g., government tax and incentive policy). Ahn &York (2011) suggest that institutional influences (e.g., tax policy, regulation, and government support) need tailored to specific industry needs.

Summarizing the institution-based view of strategic management in international business settings, the literature supports the need to include institution-based view with the resource and industry-views for success in both entry and governance. Governmental and social-cultural implications were the most significant reasons for institution-based inclusion, but many PESTLEEG considerations only become part of strategic planning under the inclusion of the institution-based view in international business.

Domestic applications

A firm or industry operating within a single country still has some institution-based implications to evaluate in strategic planning. Labor unions are one example of an institution-based consideration that firms and industries include in well-constructed strategic plans. At times governmental involvement is even necessary. Kemmerling & Bruttel (2006) research illustrates this in the Hartz reforms for the German welfare state implicating the German labor market. An example of a firm employing institution-based view in strategic management domestically is The Boeing Company limitation of the labor union’s power and their threats of frequent strikes by opening operations in South Carolina, a “right-to-work” state (Boeing’s Labour Problems, 2011).

Another consideration or factor in the institution-based view of strategic management involving domestic implications is race and class issues. Certain cultures or sub-cultures require some PESTLEEG consideration and strategic planning. Bullard (2000) suggests that industries have “dumped” in “Dixie” (the economically depressed Southern areas of the United States), capitalizing on residual impact of the de facto industrial policy (i.e., “any job is better than no job”) on the region’s ecology. He notes that less palatable jobs and industries with higher pollution or risk often are in communities of lower social-economic status. This suggests that responsible firms need to include institution-based view in their strategic planning, rather than just following the competitive (industry based) or low-cost labor (resource based) suggestive strategy to be corporately responsible and ethical. Also notes that much of the growth in the South in the 1970s was a result of a number of (institution-based) factors:

Growth in the region during the 1970s was stimulated by a number of factors. They included a climate pleasant enough to attract workers from other regions and the “underemployed” workforce already in the region, weak labor unions and strong right-to-work laws, cheap labor and cheap land, attractive areas for new industries, i.e., electronics, federal defense, and aerospace contracting, aggressive self-promotion and booster campaigns, and lenient environmental regulations. Beginning in the mid-1970s, the South was transformed from a “net exporter of people to a powerful human magnet”. The region had a number of factors it promoted as important for a “good business climate”, including “low business taxes, a good infrastructure of municipal services, vigorous law enforcement, an eager and docile labor force, and a minimum of business regulations” (Bullard, 2000).

Bullard’s (2000) report affirms the impact of political (e.g., government), economical, social-cultural, technological, legal, ethical, environmental, and the geographical-demographical implications on domestic business growth. Regardless of the ethical nature of the issues associated with the growth identified in Bullard’s report, these are factors for consideration in domestic strategic planning by inclusion of an institution-based view.

Extensions

One extension of the institution-based view of strategic management is in marketplace trust formations-especially in online markets (Pavlou, 2002). Pavlou’s research proposes that institution-based structures influence transaction success (e.g., increase market opportunity/trustworthy trading environment online) through trust (e.g., creditability and benevolence), attributed to perceived monitoring, perceived legal bonds, perceived accreditation, perceived feedback, and perceived cooperative norms. Institution-based trust is defined as “a buyer’s perception that effective third-party institutional mechanisms are in place to facilitate transaction success” (Pavlou & Gefen, 2004).

Another extension of the institution-based view of strategic management is strategic planning beyond the production, exchange, and distribution activities that are profit-centric. As firms embrace an institutional-based view of strategic management and understand many of the political, economical, social-cultural, technological, legal, ethical, environmental, and geographical-demographical factors in the environments in which they engage, many plan and implement elements of corporate social responsibility (Waddock, 2008). Corporate social responsibility, accountability, transparency, sustainability, and diversity (as opposed to hegemony) are part of a number of firms’ goals and strategic planning efforts.

Mintzberg (1978) founded the theory of emergent management theory. Mintzberg postulates that strategic planning can be too explicit and not provide for environmental turbulence. Mintzberg suggests that strategic plans form only a guideline and businesses react or adapt to the uncertain business environment (Mintzberg, 1978). Mintzberg’s theory would suggest that the institution-based view of strategic management would come later, and be the adaptive nature of emergent theory.

The extension of institution-based view to corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and ethics is a current trend. Lewis (2003) suggests that there is a rise in awareness of corporate social responsibility (CSR), and that it is a growing factor in stakeholder expectations and a vehicle for trust between business and its stakeholders. Lougee & Wallace (2008) suggest that CSR is on the rise (trending), but that the concerns (e.g., demand or expectations) are still out- pacing corporate CSR efforts.

Yang (2004) argues that regional economic integration between the Pearl River Delta and Hong Kong has transformed from being market-based (e.g., industry-based view) to being institution-based (occurring via increasing governmental communication), and that this “is consistent with the increasing regionalism occurring in various parts of the world, especially East Asia”. The evolution of economic integration was aided by multiple political events such as the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration signing, after which China allowed Hong Kong and Guangdong officials to plan infrastructure (e.g., water supply, electricity, and trains). Yang (2004) suggests that most cases of economic integration build on institution-based environments (e.g., prior establishment of formal free-trade agreements, institutions, or inter-governmental negotiations), but that the Pearl River Delta and Hong Kong integration are examples of integration efforts being accelerated once the geopolitical environment allowed formal institution-based mechanisms of integration to exist. This research suggests that the institution-based view may aid strategic planning for emerging markets, even if implemented later in the process (latency extension), and this may be a further development of application of the institution-based view.

Summarizing some of the extensions of the institution-based view of strategic management, trust in interactions and responsibility of corporations are two significant outputs that the literature suggests positively correlating with the inclusion of institution-based view. In addition, the institution-based view of strategic management adds adaptability measures to strategic plans, whether emergent as Mintzberg suggests (Mintzberg, 1978), or before entry as Michael Peng asserts (Peng, 2016).

Criticisms and Limitations and Gaps in the Literature

The institution-based view of strategic management does have critics. Singh (2007) argues that culture is not an integral component of strategy and/or has limited relevance to strategic planning. Singh (2007) acknowledges the presence of cultural discussions and content in many strategic plans, but is dismissive of its practical value. Also he argues that cited cultural impact is correlation rather than causation, and that there is lacking evidence of causal significance in operational performance.

In addition to the criticism of the institution-based view of strategic management, the literature appears to have a gap in the institution-based view of strategic management’s applicability to organic growth. Applicability of the institution-based view to the organic growth of a firm may be a limitation, and the governmental, cultural, and other factors that institution-based view brings to strategic management may be irrelevant to organic growth or static operations. It is more likely that some applicability exists, and this is an opportunity for further research, but the literature gap requires couching it as a potential limitation.

Another gap in the literature is the lack of identified methodologies or tools for weighted consideration of the various external factors (institutional factors) for risk/reward considerations. This research introduces a known industry model/tool (the FMEA) and provides instructions for use.

Value of the Theory and Future Research Opportunities

Peng (2002) founded the institution-based view of strategic management and is currently a prolific scholar using this theory. With literature lending credence to this theory, the timely application to emerging markets, the many extensions of application, and some trends and further developments-it is likely that more research will be done on the institution-based view of strategic management.

The academic exploration or epistemology of strategy (strategic management) in business generally and international business specifically is relatively a recent undertaking (Mintzberg et al., 1998). International business and/or globalization experienced exponential growth with recent technological developments, and there are a number of opportunities for further research. The institution-based view of strategic management is even younger than the academic study of strategic management-introduced by Michael Peng in 2002 (Peng, 2002). The institution-based view accommodates a number of implementation complexities in international business (e.g., PESTLEEG), and compliments good strategic planning in emerging domestic markets. There is significant opportunity for further research to scope down or deconstruct the institution-based view, as the governmental and cultural factors easily expand to the many PESTLEEG factors of emerging markets, and this view is the repository for everything that does not fit in the resource and industry views. A few of the many other opportunities for further research exist in application of institution-based view, to assorted industries and their respective regulatory and demographical environments and markets. Additionally, further research is necessary to integrate the institution-based view on strategic management with other theories (e.g., game theory or network theory). One significant opportunity for further research is the applicability/relevance of institution-based view on a firm’s organic growth-both in the extension of theory and in methods of execution.

Summarizing, there are opportunities for further research in the institution-based view, both horizontally (e.g., extensions, industries, and further applicability toward acceptance holistically in strategic planning) and vertically (e.g., proof through case studies) due to the relative newness of this theory and the significance to exponential globalization and other trends.

Research Method

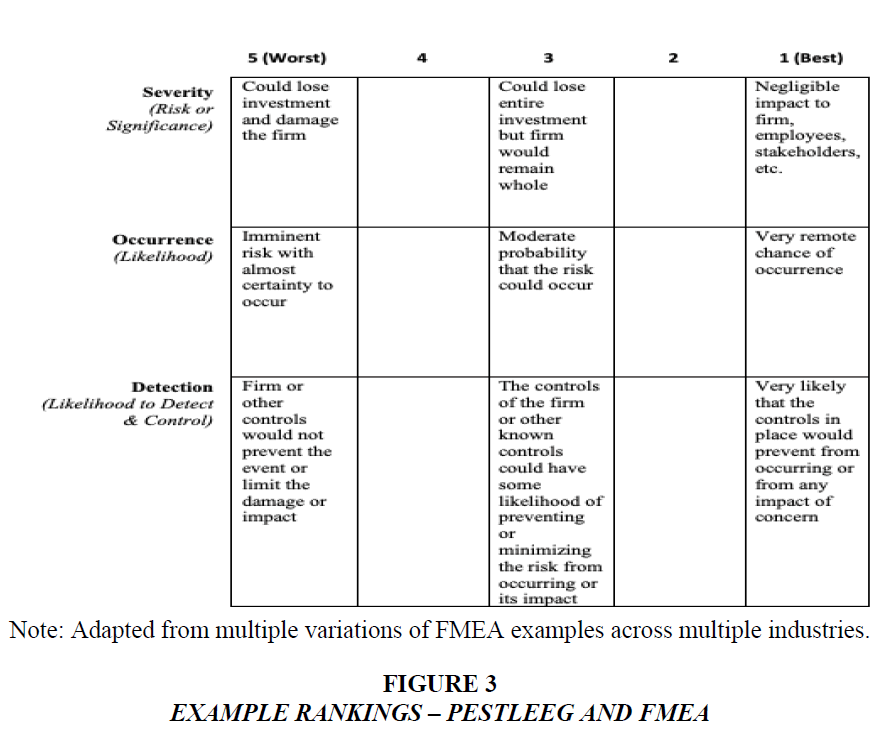

The research method suggested is “Derived” as practitioners of strategic management must use the most current data from sources such as those illustrated in Table 2 for risk analysis. The practitioner must also use market opportunity and their specific firm or industry’s data to determine risk tolerance and the risk/reward decision criteria. This is a qualitative effort as most sources do not report quantitative or numeric scores for external factors. Each evaluation of the external factors can be assessed using a FMEA methodology as illustrated in Figure 3 to assign a risk score.

This research introduces a model from industry (FMEA) and suggests utility in strategic management. This research does not analyze data or prove a model as both the data and the model can be adjusted by the practitioner to fit the specific strategic analysis. The research uses the literature to demonstrate the need to weigh external/institutional factors (different for each firm and scenario). This research is then instructional as it provides a data collection and ranking methodology.

Rating Application(s) via the FMEA Model

The PESTLEEG Factors Analysis Model is practical in utility when combined with evaluation or rating scales to use in the strategic management process. Because trade agreements, government relations, technological developments, and other factors are not constant, the institutional-based view of management in strategic planning is dynamic and somewhat emergent (e.g., Emergent Strategy - Mintzberg, 1978). Table 2 points to international research and data sources for each PESTLEEG factor and other data sources may be used as well, especially for domestic applications. Applying this data to a risk analysis model of significance and likelihood against a determined risk tolerance is necessary for strategic management decisions.

The Failure Mode/Effects Analysis model has been used for many industrial applications (Juran, 1989; Gilchrist, 1993; Stamatis, 2003; AIAG, 2008) as well as some academic research (Ben-Daya & Raouf, 1996; Ravi-Sankar & Prabhu, 2001; Teoh & Case, 2004). It is introduced here as a risk analysis methodology that compliments the PESTLEEG Model. The extension of the PEST (and other variants) analysis tools for scanning external environmental factors in strategic management and international business, to the PESTLEEG Analysis model, is recommended to further break out each factor for unique risk (or opportunity) analysis.

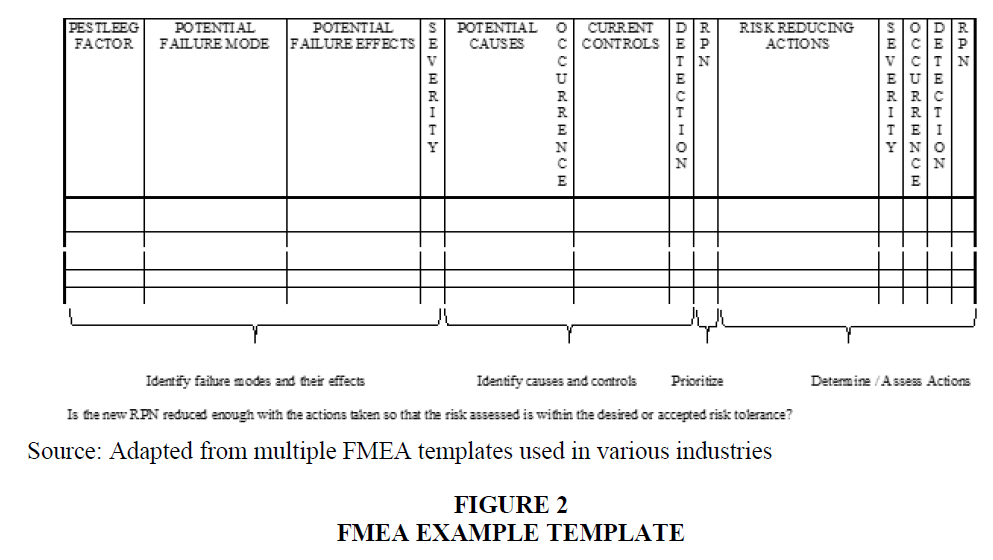

The concept of this research recommendation is to predetermine several failure modes for each of the PESTLEEG factors (as shown in Table 3) and research (Table 2 or other) each concern. The FMEA uses three factors (shown in Figure 2) and the multiple of these factors forms an aggregate Risk Priority Number (RPN). The concept is that several target environment choices can be compared using this process to determine those with higher (greater risk) or lower (lower risk) external environmental factors aligned with the Institution-based view of management. The classic FMEA rankings are severity, occurrence, and detection. In this application, we operationalize these factors. “Severity” is a scalar measure of the impact to the firm and/or its stakeholders should the risk factor/concern be realized. “Occurrence” is a measure of likelihood, as some factors could be severe if they were to occur but are considered very unlikely. “Detection” is a measure of the likelihood that the firm can control the outcome by quickly detecting and preventing it. Example ranking factors are shown in Figure 3 and can be adapted to the specific industry or firm. The RPN is [(S) Severity X (O)

| Table 3 Factors and Failure Modes – Pestleeg and Fmea | |

| PESTLEEG Factors | Example Failure Modes for Strategic Planning |

| Political | Home and target country environments are at risk of impending war or conflicts Government support programs are not investing in infrastructure or supporting trade Significant trade wars or embargos (pending or in place) Poor standing with organizational assistance and membership (e.g., WTO, WB, UN, IMF, etc.) |

| Economical | Competitive labor, goods, and/or supply chain is limited or not available Unfavorable exchange rates or tax considerations Market size, economic growth rate, degree of economic freedom, open or closed economy, middle class consumer size Limited new markets/ market channels, trade opportunities/ patterns, or investments |

| Social-Cultural | Significant deltas determined in Hofstede Dimensional Analysis (Hofstede, n.d.) that would be difficult to bridge Product and process do not relate to the target cultures or norms including linguistic and perspective factors Values, policies, and strategy do not exist for geo-centrism or poly-centrism (suggests Ethno-centrism and/or cultural hegemony) |

| Technological | Innovation cannot accelerate through combining of resources and technology level is not adequate or advantageous Infrastructure does not support the business model (e.g., internet, telephone, software, logistics, and educated workforce are limited) Production skills and instruments are not in place to equal quality and/or methods of outsourcing are limited |

| Legal | Intellectual Property (IP), copywrite, and brand protection is limited or does not exist Contracts are not enforceable and local law enforcement is corrupt Laws do not allow for mutual trade or protection of investments |

| Ethical | Local governments or rogue powers commonly extort, causing ethical dilemmas to conduct business Ranking in Corruption Perception Index (Transparency Index) Favors, exchanges, bribes, etc. are the norm and contracts (verbal and written) are non-binding with risk of latent bait and switch or further favors implicated Larger government is engaged in bait and switch or exchange rate manipulations |

| Environmental | Product or process includes dirty technologies without due controls available – negative ramifications (e.g., lead content, persistent pesticides, etc.) Ranking in Pollution and Air Quality Index Strategies are not in place (or research) to globalize to the more conservative Environmental Health System (EHS) versus taking advantage of the position (e.g., local management operating to the lower standard without legal ramifications) Process or production plans do not include responsible investment for effective EHS and environmental protections |

| Geographical – Demographical | Location is considered at high risk/vulnerability to disaster causing interruptions to the infrastructure or supply streams Nature and Nurture Endowment; Natural resources (land, oil, population) vs innovative clusters (educated workforce; creativity and innovation capabilities) Demographics for labor and linguistics are significant hurdles without significant expatriate programs Poor local acceptance or localized affordability causing risk of investment loss or limited market channels |

Conclusion

The tripod (Peng et al., 2009) of the resource-based view, industry-based view, and the institution-based view in strategic planning, is of greater holistic value than any one of these by themselves. The literature supports the gap that existed before the introduction of the institution-based view, as neither geopolitical and regulatory implications nor social-cultural factors, were adequately included in the industry-based or resource-based exclusive views. Porter’s (2008) five forces and diamond models evolved (lending credence to the institution-based view) to address the governmental/regulatory dynamics in strategic planning. There are a number of applications in international business and emerging markets or economies that the institution-based view assures are inputs to strategic planning. In addition, there are applications in domestic growth strategies, and across multiple industries. Overall, the institution-based view is a useful tool for strategic planning and implementation/execution.

There is further research required in industry applicability and solidification or maturity of the theory. There are also some gaps in the literature, especially in the applicability of the institution-based view to strategic planning for a firm’s organic growth and research/data sources for domestic target environment evaluations. The institution-based view argues that the industry-based view and the resource-based view left a gap in strategic planning and implementation, and require supplemental accountability to relevant societal and regulatory implications. Further deconstruction of the institution-based view through further research is necessary, as it broadly assumes the gaps left by the resource and industry-based views. Fitting all of the PESTLEEG considerations into a single view/perspective for strategic planning, and assuming relevance across diverse industries, suggests a need for deconstruction and further research. The gap in existing theory was recognized, and Michael Peng addressed this through the introduction of the institution-based view, but strategic planning is complex and further opportunity exists for structure through deconstruction. The institution-based view of strategic management (in triune with resource and industry-based views) is a valuable tool but requires further research for able application and implementation.

This research proposes a methodology for assessing the environment as outlined by the institution-based view, by further categorizing the various external environment factors in a PESTLEEG Analysis Model. Each factor is then evaluated for various risk or failure modes via the FMEA methodology. This assists the strategic management process in risk identification, and evaluation. Additionally, if the target environment is still attractive but the risk is greater than the risk tolerance, control or mitigation efforts can be evaluated for an adjusted risk ranking. In summary, strategic management needs to consider the institution-based view of management or external environmental factors when evaluating a target environment. This can be done by breaking these factors into discrete variables (PESTLEEG) and then researching each carefully and ranking them (FMEA) for consideration and evaluation.

References

- Aguilar, F.J. (1967). Scanning the business environment. New York: Macmillan.

- Ahn, M.J., & York, A.W. (2011). Resource-based and institution-based approaches to biotechnology industry development in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(2), 257-275.

- AIAG. (2008). Potential failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA). Retrieved from www.aiag.org

- Ben-Daya, M., & Raouf, A. (1996). A revised failure mode and effects analysis model. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 13(1), 43-47.

- Boeing’s Labour Problems. (2011). Moving factories to flee unions. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2011/04/25/moving-factories-to-flee-unions

- Bullard, R.D. (2000). Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Chandler, A.D. (1962). Strategy and structure: Chapters in the history of the industrial enterprise.

- David, F.R. (2013). Strategic management: Concepts and cases. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Evered, R. (1983). So what is strategy? Long Range Planning, 16(3), 57-72.

- Foo, C.T. (2007). Epistemology of strategy: Some insights from empirical analyses. Chinese Management Studies, 1(3), 154-166.

- Gao, G.Y., Murray, J.Y., Kotabe, M., & Lu, J. (2010). A “strategy tripod” perspective on export behaviors: Evidence from domestic and foreign firms based in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3), 377-396.

- Gilchrist, W. (1993). Modelling failure modes and effects analysis. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 10(5), 16-23.

- Hofstede (n.d.). Hofstede centre cultural tools: Country comparison. Retrieved from https://geerthofstede.com/landing-page/

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hoskisson, R., Eden, L., Lau, C., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249-267.

- International Monetary Fund Website. (2019). Retrieved from http://www.imf.org

- Juran, J.M. (1989) Quality control handbook, New York, NY: McCraw-Hill

- Kaplan, R.S., & Norton, D.P. (2008). The execution premium. Harvard Business School Press.

- Kemmerling, A., & Bruttel, O. (2006). ‘New politics’ in German labour market policy? The implications of the recent Hartz reforms for the German welfare state. West European Politics, 29(1), 90-112.

- Keohane, R.O. (1989). International institutions and state power: Essays in International Relations Theory. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Kvint, V. (2009). The global emerging market: Strategic management and economics. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kwintessential Website. (2013). Country profiles - Global guide to culture, customs, and etiquette, http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/resources/country-profiles.html

- Lee, A. (2011). Understanding strategic human resource management through the paradigm of institutional theory. International Employment Relations Review, 17(1), 65-74.

- Lewis, S. (2003). Reputation and corporate responsibility. Journal of Communication Management, 7(4), 356-366.

- Liu, D.M. (2014). The model F.I.V.E. in strategic management. Retrieved from https://foxtale.georgefox.edu/

- Liu, D.M. (2015). PESTLEEG factors framework: A comprehensive external environmental analysis for international management. Retrieved from: https://vdocuments.site/pestleeg-factors-framework-for-global-business-environment-evaluation-by-dr-david-ming-liu.html

- Lougee, B., & Wallace, J. (2008). The corporate social responsibility (CSR) trend. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 20(1), 96-108.

- Lu, Y., Tsang, E.K., & Peng, M.W. (2008). Knowledge management and innovation strategy in the Asia Pacific: Toward an institution-based view. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(3), 361-374.

- Mintzberg, H. (1978). Patterns in strategy formation. Management Science, 24(9), 934-948.

- Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (1998). Strategy safari- A Guided tour through the wilds of strategic management. The free press New York.

- Morrison, M. (2007). Pestle analysis tool. Retrieved from https://rapidbi.com/the-pestle-analysis-tool/

- Oliver, R.W. (2001). Real-time strategy: What is strategy anyway? Journal of Business Strategy, 22(6), 7-10.

- Pavlou, P.A. (2002). Institution-based trust in interorganizational exchange relationships: The role of online B2B marketplaces on trust formation. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(3), 215-243.

- Pavlou, P.A., & Gefen, D. (2004). Building effective online marketplaces with institution-based trust. Information Systems Research, 15(1), 37-59.

- Peng, M.W. (2002). Towards an institution-based view of business strategy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 19(2/3), 251.

- Peng, M.W. (2016). Global business. Cengage learning.

- Peng, M.W., Sunny, L.S., Pinkham, B., & Hao, C. (2009). The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(3), 63-81.

- Peng, M.W., Wang, D.Y., & Jiang, Y. (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 920-936.

- Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of growth of the firm. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pickton, D.W., & Wright, S. (1998). What’s SWOT in strategic analysis? Strategic Change, 7(2), 101-109.

- Porter, M.E. (1979). How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, 57(2), 137-145.

- Porter, M.E. (2008). The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 25-40.

- Priem, R.L., & Butler, J.E. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 22-44.

- Ravi-Sankar, N. & Prabhu, B. (2001). Modified approach for prioritization of failures in a systems failure mode and effects analysis. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 18(3), 324-336.

- Richman, B.M. (1965). Significance of cultural variables. Academy of Management Journal, 8(4), 292-308.

- Ross, J.W., Weill, P., & Robertson, D.C. (2006). Enterprise architecture as strategy: Creating a foundation for business execution. : Harvard Business Press.

- Rumelt, R. (2011). Good strategy bad strategy: The difference and why it matters. New York, NY: Random House.

- Singh, K. (2007). The limited relevance of culture to strategy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(4), 421-428.

- Stamatis, D.H. (2003). Failure mode and effect analysis: FMEA from theory to execution. Quality Press.

- Teoh, P.C., & Case, K. (2004). Failure modes and effects analysis through knowledge modelling. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 153, 253-260.

- Tzu, S. (2012). The illustrated art of war. Courier Corporation.

- United Nations Website. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.un.org

- Van Essen, M., Heugens, P.P., Otten, J., & Oosterhout, J.H. (2012). An institution-based view of executive compensation: A multilevel meta-analytic test. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(4), 396-423.

- Waddock, S. (2008). Building a new institutional infrastructure for corporate responsibility. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 22(3), 87-108.

- West III, G., & DeCastro, J. (2001). The Achilles heel of firm strategy: Resource weakness and distinctive inadequacies. Journal of Management Studies, 38(3), 417-442.

- Wickham, B. (2014). Taking your business global: The role of language and culture. Journal of Property Management, 79(1), 36-37.

- World Bank Group Website. (2020). Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org

- World Trade Organization Website. (2020). Retrieved from http://www.wto.org

- Yang, C. (2004). From market-led to institution-based economic integration: The case of the Pearl River Delta and Hong Kong. Issues and Studies - English Edition, 40(2), 79-118.

- Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341-363.

- Zhou, J.Q., & Peng, M.W. (2010). Relational exchanges versus arm’s-length transactions during institutional transitions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27(3), 355-370.