Research Article: 2020 Vol: 19 Issue: 3

Family Businesses (FBS) in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Review and Strategic Insights

Saad Darwish, Kingdom University

Anjali Gomes, Kingdom University

Venus Bunagan, Kingdom University

Abstract

Economic liberalization and massive expansion after 1990 have led to an industrial base that has not only generated opportunities for growth for many in recent years, but has also tested their capacity to respond to them. Some have chosen to follow the role of custodian of their existing wealth and have followed the path of preservation, while others have followed a more entrepreneurial path. One of their key resources is their children, and the security and health of their families is their primary concern. A major dilemma some of them have faced, especially in the last two decades since industrialization began, is to choose between risk combinations and returns to business growth and the preservation of family wealth. Family is one of the oldest survivors as a social institution, but family business has only become the main branch of the company in recent years. This article reviews the literature on family business in the future prospect of GCC economies. In general, descriptive and empirical articles that typically focus on family business dominate this literature. This paper also discusses some of the main family business problems in GCC countries.

Keywords

Family Business, Strategy, Leadership Succession, Economic Growth.

Introduction

It is easy to ignore the fact that some of the most prosperous companies are family businesses in the age of corporations with global appeal, multinationals and boarded-domestic corporates. Family businesses are an important part of every economy and it is a particular challenge to learn how they can adapt and develop competitive advantages to changes. Family business offer economic growth and infrastructure for wealth creation. Statistics show that family business accounts for between 65% and 80% of all existing companies worldwide (Goto, 2016). Family businesses account for two-thirds of all businesses worldwide, generate more than 70% of global GDP, and account for 50–80% of jobs in many countries (Galván et al., 2017). The European Family Business Organization shows that 60-90% of all firms in various countries in Europe and 40-50% of the region's private employment is family businesses. Ninety percent of all companies in Canada and the United States are family-owned, while in Australia, approximately half of all businesses are claimed to be family businesses (Rodríguez-Ariza et al., 2017).

Family-owned businesses also account for a significant part of the national business community and make a significant contribution to economic growth all over the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Family-owned businesses contributed about 60% of the region's gross domestic product and employed more than 80% of GCC's labor force (Purfield et al., 2018). Like their peers in the GCC, 90% of the private sector in the UAE and Saudi Arabia are family-owned businesses (Farouk Abdel, 2017). Because of the various challenges faced, FBs have low survival rates in GCC such as increased market rivalry and business life cycle maturity, insufficient resources to meet business and family needs, weak leadership in future generations, resistance to change, lack of competitiveness, conflicts between family successors and desperate family needs and objectives. In the GCC nations, the average life of family business is only 23 years (Al-Barghouthi, 2016). Such statistics show the significant importance to the GCC economy of family business survival. In the following literature review, we will scan research that tackles the issues of networking, generating knowledge, innovation, challenges, similarities & differences. The role of universities that adopt entrepreneurial courses is of influence on boosting entrepreneurship business. Then proposes some thoughts on future research within this context.

Literature Review

Networking and Innovation in Family Business

The review of the literature is based on the systematic review process defined by (Pittaway et al., 2004 & 2005; Centobelli et al., 2019). They are distinguished in the field of literature reviews concerning entrepreneurship. Therefore, the literature of this study considers interacting and concentrating on risk-taking, retrieving and discovering new markets and advancement of technology initiated by family business pioneers. Family Business, which do not formally or informally network, they have limited knowledge base in the end. Hence, there should be exchange relationships between and among similar businesses.

The network relationships of suppliers, customers and intermediaries other professional associations are very important inputs to networking. There might be failures of networks, but these are attributed to conflicts, lack of scale, lack of infrastructure and external disruptions. On the other hand, the review of literature needs further exploration of networking and forms of innovation in family business. These include the process of organizational innovation and sometimes the need of inter-disciplinary research in various areas (Pittaway et al., 2005; Darwish & Bunagan, 2019).

One of the objectives of the current research is to identify the role of the family business in the economic growth of the GCC. Using strategies of networking and innovation are significant ways by which family businesses are able to develop new products and possibly enter new markets. Family businesses are either small or medium scale, or a number are reported to be having experienced failures due family conflicts, to lack of infrastructure and external challenges like competition.

Knowledge within SME Family Business

The research provides a review on how the SME family business use and acquire knowledge. The research explained how they should acquire knowledge and use this knowledge as an asset in businesses. It discussed the three main areas of how SME family business acquire and utilize knowledge:

1. Focus on the influence and abilities of the entrepreneur in family business to source-out, use and knowledge. Understanding how entrepreneurs and managers learn from others, and how others learn from entrepreneurs and managers, has been examined in research exploring the cognitive framing of “entrepreneurial knowledge structures” by which opportunities are recognized, created and pursued

2. The need for research that focuses on the systems and human capital that searches for knowledge exploration and exploitation. By broadening the scope of dissemination, emphasizing evidence and the form of evidence, the review methodology is designed to inform policy practitioner (Darwish, 2014b)

3. Research, which focuses on institutional context regarding Government policy and its effectiveness.

Family businesses utilize their own immediate members of the family; there is a need to examine the capabilities of those who would frontline the management specially the operations. Willingness alone from human capital is not sufficient to deliver the needed knowledge to plan, formulate and implement the policy and business framework of the business. Accordingly, the knowledge is always embedded with human capital and a strong driving force to family business success (Pittaway et al., 2005; Brines et al., 2013).

Development of an Entrepreneurial University & Family Business

Creating such a link is vital to establish a base of well-equipped entrepreneurs. Thus, SME family business will thrive and the economy will boost. Both formal and informal education shape the entrepreneurial role of universities (Darwish, 2014a). Educational institution plays a vital role in transforming the raw knowledge of learners on entrepreneurship of business into a full-and ripened entrepreneur or businessperson. Universities are processing such as research and teaching. The results highlighted the significant roles of the university and its internal stakeholders in enhancing knowledge management strategies.

The focus is to encourage the academicians, industry practitioners and policy-makers to utilize knowledge management tools and practices in universities to support the entrepreneurial development of its graduates and acquire a positive impact on innovation ecosystems. Hence, the concept of developing a more entrepreneurial university highlights the need to examine how specific factors and knowledge management processes are influencing the universities’ performance. Today ‘though, there is still lack of these factors integrating the concepts with strategic knowledge management processes (Centobelli et al., 2019).

Succession in Family Business

In a family business planning for succession can be somewhat challenging in the future. The process of succession planning must be proactive so that the business is not affected by the changes that usually occur with the change of the owner. Clear strategies must in place to consider the succession process, which could be time consuming. Scholars interested in the family business are inclined to follow practice-oriented research methods. Thus, many researchers use case study methodology as a way to carry out their research work, which can help in the understanding of the family business dimensions. Many of the family businesses heads do not have an official retirement plan or succession plan. This can emerge as a field to be researched in the future (Zahra & Sharma, 2004; Darwish, 2018).

Similarities, Differences & Future Research

As the study, shows within the GCC countries there are similarities in the family business in terms of fewer turnovers. Especially at the managerial level, usually members get involved at a very young age with the family business so there is a wealth of knowledge as well as a strong bond within the members. At the same time, there is variation due to the infrastructure, which is usually informal in nature. This is true for the structure of the organization. In different countries of GCC, the market size differs as per the demography, which affects the family business. In some of the countries, the family business resist the inclusion of a non-family member as this may give rise to conflicts among the family members and can hinder the performance of the members. This can be another area for further research.

From this conclusion, it is very clear that Family Business in GCC is still in a paradoxical state. Hence, there is a wide scope for further research in it by way of extending the same to different family business. Further, the same study can be conducted in GCC countries by taking huge sample size and it could be possible to undertake an empirical study. A comparative study could also be undertaken between different GCC countries. There is also a scope that the data could be collected from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data could be collected through administering a structured questionnaire among the Family Business in GCC while secondary data could be from the databases, websites, theses and dissertations.

Problem Statement

Scholars have published a variety of topics related to family business, including conflict, governance, creativity, class, ethnicity, business efficiency, succession, family power, leadership, management and theory in GCC (Oudah et al., 2018). Few studies have incorporated all the important factors of survival success, and future aspects of family business in GCC. In general, each performance factor is discussed separately. Nevertheless, in all the earlier studies authors have not prioritized the importance, especially in the context of the GCC, of each failure factor for the future by defining all known factors in literature and investigating current family businesses. This study is therefore this study is pioneering in discussing all the failure factors, challenges, case studies, and future prospect of family business in GCC. Therefore, the objectives of this research are:

(1) An historical overview of family business in GCC

(2) To identify the role of family business in the economic growth of GCC

(3) To highlight the factors responsible family business failure in GCC

(4) To explain the different case studies

(5) To discuss the future prospects of family business in GCC

Research Methodology

In the present paper the literature review was developed through identifying the problem statement based on the literature search, an in-depth survey through scholarly articles and various other databases was used to investigate the Problem Statement. Extensively previous research findings were reviewed as a part of Desk analysis. The researchers evaluated these data in order to determine the significant contribution to the review of literature (Cheng, 2014). Finally, we present conclusions based on the discussion pertinent literature. Essentially the theoretical literature review revolves around a critical reading of existing literature and then summarizing and penning down the review

Conducting a literature review is a vital component of the research process. Familiarity with the previous research and theory in the area of the study would help in conceptualizing the problem, conducting the study and interpreting the findings. This study viewed the future insight of FBs in GCC in the light of previous research. The purpose of the literature review on family business in GCC is to identify the related facts in the research work that were determined by other authors through their research in the similar field of work and to know the outcome of their research. The literature reviews will throw light on the broad spectrum of family business activities in GCC.

Empirical Overview of Family Business

Past researchers have published on a variety of family business related topics, including conflict, governance, innovation, gender, ethnicity, business performance, succession, the influence of family, family capital, leadership, management and extant theory. We will explore few of current research. Hategan et al. (2019) found that ownership, governance, management and estate are the key participation in family business, and they have a relationship with their company performance. The involvement of families perceived by the parties concerned is strongly linked to both a reputation as a family company and perceived financial performance, according to Santiago et al. (2019). In addition, the study found that the relationship between family involvement and perceived financial performance is partly mediated by the family company's reputation. Santiago et al. (2019) reported that the role of families as viewed by the players is strongly related both to the prestige of the family business and to its financial performance. Integrating family and non-family members in the top management team is beneficial to the business performance. Family businesses are gaining more from local integration than non-family businesses therefore having a greater influence in rural areas. Decisions concerning financing are directly influenced by the personal attitude of the decision-maker, who in turn was influenced significantly by family and social pressure.

In GCC, Cammett (2018) The Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has had a positive influence on the corporation performance of family companies, their leadership and their more conservative and risk-averse characteristics. Likewise, the best practice is to integrate these elements into the GCC firms. Buheji (2017) said GCC family businesses need leaner governance practices which help maintain their legacy for more Generations while maintaining their capacity building. The study discussed how GCC FB's ability to play a more vital role in its economic and social environment could be increased by using the inspiration currency.

History of Family Business in GCC

In accordance with their special relations, geographic proximity, similar political systems, based on Islamic faith, joint destiny and common objectives, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was formed by six countries in the Prior to the 1940s, 28% of economies in the Gulf depended on trade (Smith, 2019). While trade dominates the economy of the country, the majority of family businesses begin while small food and textile traders. During the 1940s–1960s, 56% of businesses established during this period, especially in construction and financial services, following the discovery of petroleum, since they benefited from the growth of the oil industry mainly in Saudi Arabia (Manama, 2016). The GCC's economic development began with the oil-driven economic boom in the 1970s and 16% of startups covering many business sectors, with an emphasis on retail business (Delgado, 2016).

In the 1970s and 1980s, GCC traders often only acceded to the services of the rapidly growing oil-fed GCC economies as an intermediary and access broker for international businesses, which supply the majority of real goods (El-Katiri, 2016). Neither of these is as dependent on the state as it was on the first petroleum boom in the 1970s and beginning of the 1980's. The GDP is higher than in the era under study. The private sector was not as neglected in the overall economy as it was in the 1970s during the oil feed boom of the 2000s. The activity of large local businesses, which operate major production plants, private universities, clinics and universities, banks, top quality retail and hotel chains and contractors employing tens of thousands of building workers, is now much more substantial . Since the first oil boom, the private sector in the Gulf has made great strides, and most of its operations still reflect more advanced recycling than autonomous diversification. Perhaps critical of all because of its political role, its interests are strongly opposed national employment and few investment opportunities (Kamrava et al., 2016; Soto Merino, 2015).

Family Business Contribution the Economic Growth of GCC

The GCC has some of the world's fastest growing economies, mostly because oil and gas revenues are increasing with reserves-backed buildings and construction booms. The majority of these economically affected economies has stabilized and is again growing rapidly despite recent economic downturn. Family businesses constitute approximately 90% of the private sector economy, and they have a long history in the GCC, making up a large segment of the region's gross domestic product, are one of the main pillars of the economy. In the GCC, 90% of businesses produce 80% of the region's GDP, 75% of private sector industry and 70% of the work force (Biygautane, 2017). Many of these businesses have successfully established collaborations with global brands that generate substantial wealth and give consumers better value see Table 1.

| Table 1 Family Business Controlled GDP (1990-2000) | |||

| Country | GDP | GDP Controlled by Family Business | % OF GDP |

| Bahrain | 3.3 | 2.3 | 70 |

| Kuwait | 16.8 | 6.3 | 37 |

| Oman | 14.0 | 3.5 | 25 |

| Saudi Arabia | 104.0 | 34.1 | 33 |

| UAE | 30.3 | 19.3 | 64 |

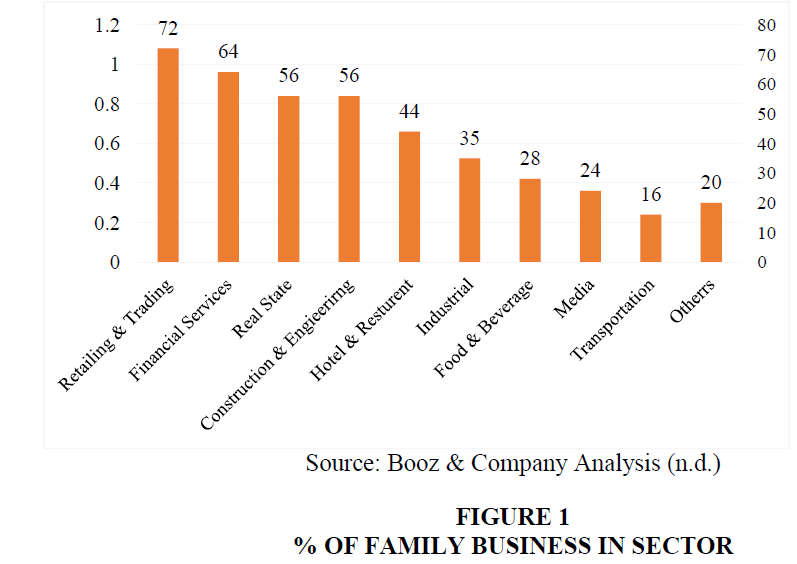

In the 2000s, the GCC underwent a decade of broad economic reforms and liberalization. Local businesses have typically benefited more than international players have from the economic opening of new industries and transition of functions from state to company. In addition, different developing countries may need multinational companies for their resources but not necessarily for their local capital. In sectors such as education, health care, telecoms, heavy industry and air transport, which were partly or completely state-controlled up to the 1990s, GCC now plays a more profound role (Mishrif & Al Balushi, 2017) (Figure 1).

Large local businesses operate large-scale manufacturing plants, private schools, clinics and universities, banks, high-class retail and hotel chains and contractors with tens of thousands of construction workers. Eighty percent of the jobs in GCC, provided and occupied by private companies, and primarily occupied by foreign employees (Ulrichsen, 2016). The sheer number of private sector jobs created in the GCC is immense, but they are mostly low pay, low-productivity jobs held by foreigners because of a factor-intensive growth model that restricts private diversification, and that in the end is unstable both politically and economically. The reliance on external workers in the private labor market is equally important in isolating the GCC businesses in the broader political economy of Gulf Monarchies.. At least in Bahrain, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, government jobs have reached their limits. When people are growing and seeking jobs, and local companies are not generating jobs that are appropriate, the tension is on the rise. GCC corporations have no organic position in a social gulf contract, based on state employment and other types of state-orchestrated rent allocation, without substantial work for locals or tax contributions. In fact, the current employment trends discourage productivity improvements as well as transitions into more technology-intense production based on greater qualifications, not to mention nationals from the private economic cycle. It is too easy to produce returns using low-tech, but cheap and easily managed, unqualified semi-qualified labor from the developing world.

The growth of the private sector in the GCC has been factor-intensive, relying on the comparative advantages of factor prices resulting from a number of State support policies. This model's reverse side is a poor catalyst for economic change, technical advances, and the dedication to research and development that all the governments of the world are looking for. In addition, the overall productivity factor of the GCC economies has declined significantly since the 1980s. Free labor migration and cheap energy have enabled GCC companies to grow production by growing labor and energy inputs instead of increasing productivity.

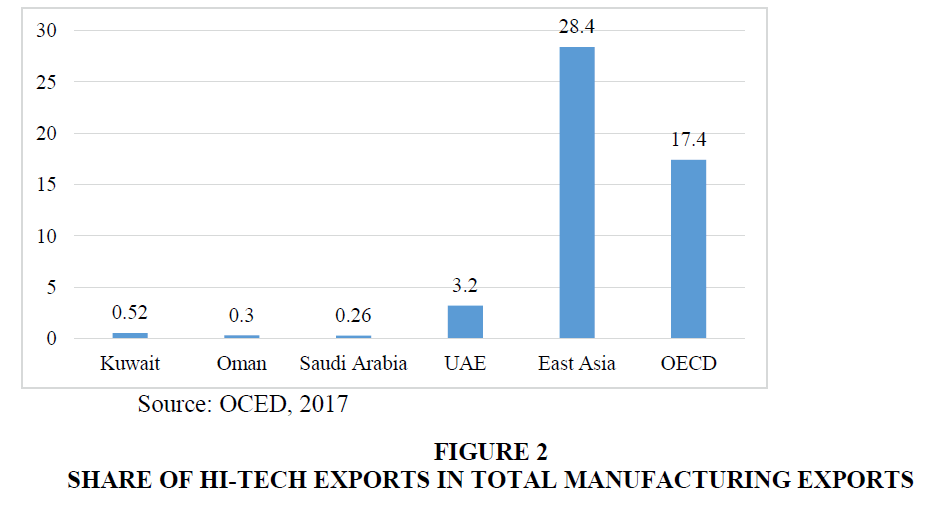

Nevertheless, GCC businesses are running badly. Nonetheless, they are primarily based on simple technology and are extremely limited in their contribution to the knowledge economy, research and innovation. Unlike successful industrialists in East Asia, GCC government support is largely not contingent on technology improvements and the GCC has failed to experience the resource shortage that has forced advanced Asian manufacturers to develop new technologies. In the case of data available for manufacturers in all GCC countries, investment in research and development accounts for around 0.1% of GDP, compared to around 2% for OECD economies. The percentage of high-tech exports is lower in magnitudes than other world regions see figure 2. The proportion of high-tech exports to the total GCC production exports is in orders below that in other world regions and, if data are available, R&D expenses represent about 0.1% of GDP compared in OECD economies to about 2%.

In the history of GCC family businesses, philanthropy initiatives throughout the area have also been a tradition (Johnson, 2018). In addition to NGOs, non-profit organizations (NPOs), cooperatives, social firms and charities, they are key players in the region's third sector. The growth of family businesses in the area is due to the entrepreneurial spirit of the generation that created the strong national ties they established and the economic conditions that led to business during the 20th century (Richards et al., 2016).

Main Problems Facing GGC Family Business

Currently, family businesses face an uncertain worldwide financial landscape and companies all over the world face immense challenges and changed business environments. The current world economic slowdown, along with greater competition from regional and global companies across industries and the GCC's “democratization” of business development, will force family enterprises to concentrate on the scaling up of businesses, performance improvement and new talent attraction. In the next few years, many families will probably face limited cash. There will be a need for new investments to survive and thrive in a more competitive environment. In the next ten years, many family businesses will have to deal with the difficulties presented over passing corporate control to a third generation, in addition to reacting to these external pressures and challenges.

GCC has a critical transition phase of approximately 80 percent of family enterprises, from the first to the second or third generations (Buheji, 2017). The Arabian Gulf is dynamic in terms of succession planning. GCC family enterprises are large families, which present the families of their third and fourth generation cycles. A large number of family shareholders characterize this. Further, family members who might have different opinions about the management of the family company, such as its future path, economic decisions and who should and can run the business may increase the chances of dispute and controversy. The board and management roles of the family members in the company could also have conflicting views and concerns.

As shareholders increase and start to include both non-family members and family members, it is becoming more difficult to control corporate strategy and policymaking centrally. Transferring control to the third generation means cousins are now in control of an earlier sibling company with the same mother, different mothers and a weaker family relationship and obligation. Large family sizes push family businesses to grow as fast as possible in order to retain the resources of family members and units. Currently, average size of GCC families (the traditional family business) will expand at 18% annually only for generations to sustain the same level of wealth. In transition, only 15% of family businesses are likely to survive. However, the study shows that only 17 percent of GCC family businesses have in place an efficient method of determining roles and obligations for the next generation.

In transition, only 15% of family businesses are likely to survive. However, the study shows that only 17 percent of GCC family businesses have in place an efficient method of determining roles and obligations for the next generation. This situation presents two main challenges: management succession and ownership succession. Due to the difficulties of the succession, one main danger during the transition is to break large family-owned businesses. The lack of organizational and legal structures in the GCC also hampers the growth of family business.

An obstacle to a smooth transition is the lack of an appropriate corporate governance system in the family businesses of the GCC. Corporate governance is a centralized decision-making mechanism that falls short of international standards. Such family businesses compete with global players today; but they retain a conservative-conventional style of management focused on patriarchal traditions rather than creativity and flexibility. Experts have said that GCC conventional management strategies need to shift in the light of globalization today. In a context these businesses are, now competing against global companies. In global companies, human resource management base their work and selection on skills and not blood ties. Family businesses need to hire new managers from outside the family to be competitive. Preparing for the transition to new leadership is an opportunity for family businesses to establish relationships with non-family business managers and professionalize their company and their network.

The large family size places considerable pressure on the family business to grow rapidly and quickly so that every family member has the same level of wealth over generations. A study concluded that in order to maintain the same level of wealth, the average GCC family business had to expand at 18 percent a year (Bakar et al., 2015). Therefore, it is possible for decisions that are solely linked to business management to be focused on competing goals such as personal wealth impacts, emotional attachment to companies and properties, or personal prospects for jobs. As the family members expand, with the potential for more female shareholders, the issue of the role of women in the family business of the GCC also arises. Most family businesses know that women are more and more involved as founders, administrators and members of the board. In some family businesses (relatively young and emerging generations) have gained prominence with presence in retail, political, immobilization, hospitality and many other industries as large as diversified conglomerates. In the face of increasing competition within the region and worldwide, they are a facing external economic pressures such as the need internationalization and standardization.

These challenges are connected and complicated. In the light of the principles of Sharia law and inheritance laws, succession planning should be carried out in different ways on several issues, including the division of voting rights and ownership and redistribution of the voting powers of members of families (Dewi & Dhewanto, 2012).

Succession needs in the GCC are restricted in contrast with their western counterparts, the access, applicability and enforceability of a legal framework is limited. It poses several challenges if families allow the transition of control and ownership of businesses to the next generation. Only three in six nations, such as Bahrain, Qatar and UAE, have rules and procedures for the establishment of a family trust, which is a common legal structure. This is usually used to maintain family fortune, assets and consolidated business power. The Sharia Law adopts Waqf Al Ahli (In the legal context, waqf means detention of a property so that its produce or income may always be available for religious or charitable purposes). This may poses problems in addition to the limited flexibility of family trusts (The presence of special laws or a clear prevalence of Waqf used as a vehicle of succession does not lie with all of the GCC jurisdictions (Ramady, 2005). In addition, if a serious imminent family conflict occurs, the right to enter into arbitration or to form special tribunals for Waqf from the Sharia Court is not available in every country.

Large and growing GCC families need preventive measures and conflict resolution mechanisms before they hit the courts. Confidential mediation and arbitration can assist the family in resolving disputes in a friendly and confidential way, while lawsuit can lead to family conflict being publicly disclosed. Family businesses are developing internal conflict resolution guidelines and processes and dealing with issues like property transfer. Family members readily challenge the Jurisdiction of GCC and that, if not in line with Sharia principles.

Succession and Failure Factors of Family Business in GCC

Research shows that about 70% of family-owned businesses struggle, or is sold before the second generation has an opportunity to take over (Ali & Ali, 2018). Data from the Family Business Institute indicates that only 30% of families live in the second, 12% in the third, whereas only 3% in the fourth and after generation (Chiang & Yu, 2018). Business divorce1 is a big reason for the failure, which can be as painful as regular divorce. This is particularly true for a family business. The lack of entrepreneurship, lack of trust among family members, inadequate management system, mistreated management capacities and in satisfaction between employees who are not familiar (Husien et al., 2019) are the reasons why family companies may fail. In some cases, there are factors behind family business successes; these are a flat structure of their management, and making quick decisions. They also invest not only in training of their employees but their family members are well trained. Their business have a robust succession plan which nurture and develop younger members of the family who are interested in joining the company, ensuring that they are capable of succeeding.

The norm is that a family business exists when the founder (the first generation) introduced a competitive product into the market. The second-generation manager's skills and knowledge (say, the oldest child) may not be as strong as the founder. Often managers of the second generation do not adopt new production techniques that hold production costs down. In other cases the market changes, consumer expectations change, but the business also does not cause rivals to lose their market share. The fear of changing methods, processes, products or even businesses could, in principle, lead to family business failure. The GCC countries have a good chance diversification, which is established through creativity and entrepreneurial skills.

The level of innovation and growth of an economy has been associated with the level of preparation and effectiveness of its entrepreneurs by much business literature. Three important factors have to be taken seriously by the GCC Governments and their enabling institutions in order to guarantee growth and stability of GCC companies (Miniaoui & Schilirò 2016). Such factors include the schooling of entrepreneurs, the creation of entrepreneurs and corporate management of companies.

SME family business is not professionally run as large businesses. In general, owners and managers spend little money on self-development and training in human resources. The degree to which management and staff are educated and trained is owing to leadership, communication, productivity and efficiency. Some of these companies have adopted the idea of professional management, but very few have taken on corporate governance. The summary of why do family businesses fail? is given below (SmallBusiness, n.d.).

1. No Separation between Business and Family

2. Lack of Trusted Advisors

3. Promotion of Unqualified Business Members

4. Conflicts within the Family

5. Failure of Good Succession Planning

6. Older Generations Not Wanting to Give up Power

7. Failure to Address Governance

8. Different Generations, Different Visions

9. Families Focus on Estate Planning Rather Than Management Training

10. Exclusion of Certain Family Members

11. Failure to Take Advantage of Familial Benefits

12. Always Being Available to Family

13. Heirs Lack Financial Education

14. No Fundamental Business Education

15. Lack of Trusted Advisors

16. Running a family business is nothing like running a standard business operation.

Conclusion

The position of family business in the Gulf States is paradoxical. It operates on a large scale, which is globally integrated, and contributes to the bulk of national capital development. It has achieved high levels of managerial maturity far ahead of its peers in the broader GCC area. Family business has taken good advantage of the GCC's comparative advantages, but has not used them as stepping-stones into the knowledge economy. Seeing declining profitability and failing to deliver quality jobs to GCC people, governments of GCC continue to push for economic policymaking in support of entrepreneurship and family business.

While merchant politics has strong historical roots in several GCC countries, Gulf businesses are less a political leader. This is in part due to familiar reasons from other regions and ages, especially the emergence of mass politics and middle-class identities, which have eroded the authority of traditional merchant elites as community leaders.

Unless GCC businesses are ever to emerge from the State's shadow, their jobs of nationals must be increased first. That means moving away from factor-intensive production, a concentrate on technological improvement and a focus on building local human capital. It would also require policy changes outside corporate control, in particular, a reduction of jobs in the public sector that currently decreases national opportunities for education and raises their salary expectations. This is hard to imagine without the GCC social contract being fundamentally redesigned, replacing relatively less distortive forms of distribution (such as wage subsidies or cash aid) with government employment. Strengthened local employment would probably reduce corporate income in the short term, but could in the long term give businesses a much safer and more independent political stance. It could become a true bourgeoisie that can negotiate on an equal footing with the state, and other social forces for the welfare of the state.

The role of the organization as mentioned mainly results not from personal failure, but rather from structural forces. It would be difficult for the best entrepreneurs to emerge as capital-rich and omnipresent as the GCC from the shadow of a regime. This does not, however, mean that more future-oriented management will not improve the situation in the future. Such leadership will address issues of tax, distribution and jobs thoroughly and include a willingness to sacrifice for the sake of long-standing growth in the short term. For now, Gulf's market position is probably too secure to take these strategic moves.

End Notes

1A colloquial term used to describe the separation between business owners.

References

- Al-Barghouthi, S. (2016). Passing the Torch, family business succession, case study, Bahrain. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(1), 279-294.

- Ali, M.Z., & Ali, S.M. (2018). Why are family owned businesses unable to sustain beyond the second generation. Global Management Journal for Academic & Corporate Studies, 8(2), 128-143.

- Bakar, A.R.A., Ahmad, S.Z., & Buchanan, F.R. (2015). Trans-generational success of family businesses. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 8(3), 248-267.

- Biygautane, M. (2017). Infrastructure public–private partnerships in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar: Meanings, rationales, projects, and the path forward. Public Works Management & Policy, 22(2), 85-118.

- Booz & Company Analysis (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mbaskool.com/brandguide/management-and-consulting/4262-booz-and-company.html

- Brines, S., Shepherd, D., & Woods, C. (2013). SME family business innovation: Exploring new combinations. Journal of Family Business Management, 3(2), 117-135.

- Buheji, M. (2017). Inspiring GCC family business towards lean governance: A comparative study with Japanese FB'S.

- Cammett, M. (2018). A political economy of the Middle East. Routledge.

- Centobelli, P., Cenchione, R., Esposito, E. (2019). Management decision. International Journal of Management Reviews, 57(12).

- Cheng, Q. (2014). Family firm research-A review. China Journal of Accounting Research, 7(3), 149-163.

- Chiang, H., & Yu, H.J. (2018). Succession and corporate performance: The appropriate successor in family firms. Investment Management & Financial Innovations, 15(1), 58.

- Darwish, S. & Bunagan, N. (2019). Innovation in energy systems: Paradigms in operation in business and development. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 8 (8).

- Darwish, S. (2014a). Education and human capital development in Bahrain: Future international collaboration with Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 3, 321-334.

- Darwish, S. (2014b). The role of universities in developing small and medium enterprises (SMEs): Future challenges for Bahrain. International Business and Management, 8(2), 70-77.

- Darwish, S. (2018). Succession planning, Bahrain society for training & development.

- Delgado, P.A.A.D.L. (2016). The United Arab Emirates case of economic success: The federal government economic policies.

- Dewi, A.C.E., & Dhewanto, W. (2012). Key success factors of Islamic family business. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 57, 53-60.

- El-Katiri, L. (2016). Vulnerability, resilience, and reform: The GCC and the oil price crisis 2014-2016. El-Katiri, Laura, New York: Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy.

- Europa World Year Book. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Europa_World_Year_Book

- Farouk Abdel Al, S., Jabeen, F., & Katsioloudes, M. (2017). SMEs Capital Structure Decisions and Success Determinants: Empirical Evidence from the UAE. Journal of Accounting, Ethics and Public Policy, 18(2).

- Galván, R.S., Martínez, A.B., & Rahman, M.H. (2017). Impact of family business on economic development: A study of Spain’s family-owned supermarkets. Journal of Business and Economics, 5(12), 243-259.

- Goto, T. (2016). Family Firms’ Transformation to Non-family Firms During 1920’s-2015. Journal of Japanese Management, 1(1), 44-59.

- Hategan, C.D., Curea-Pitorac, R.I., & Hategan, V.P. (2019). The Romanian family businesses philosophy for performance and sustainability. Sustainability, 11(6), 1715.

- Husien, S., Kirana, K.C., & Hermuningsih, S. (2019). Falling down the kingdom: Culture and tradition on family business succession. Review of Behavioral Aspect in Organizations and Society, 1(1), 95-108.

- Johnson, P.D. (2018). The growth of institutional philanthropy in the United Arab Emirates.

- Kamrava, M., Nonneman, G., Nosova, A., & Valeri, M. (2016). Ruling families and business elites in the Gulf Monarchies: ever closer?.

- Manama, B. (2016). Economic diversification in oil-exporting Arab countries. In Annual Meeting of Arab Ministers of Finance.

- Miniaoui, H., & Schilirò, D. (2016). Innovation and Entrepreneurship for the growth and diversification of the GCC Economies.

- Mishrif, A., & Al Balushi, Y. (2017). Economic Diversification in the Gulf Region, Volume I: The Private Sector as an Engine of Growth. Springer.

- OCED-Organisation for Economic Co?operation and Development. (2017). Enhancing the contributions of SMEs in a global and digitalised economy. In Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level, Paris.

- Oudah, M., Jabeen, F., & Dixon, C. (2018). Determinants linked to family business sustainability in the UAE: An AHP approach. Sustainability, 10(1), 246.

- Pittaway, L., Robertson, M., Munir, K., Denyer, D., & Neely, A. (2004). Networking and innovation: a systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5(3?4), 137-168.

- Pittaway, L.A., Thorpe, R., Macpherson, A., & Holt, R. (2005). Knowledge within small and medium-sized firms: A systematic review of the evidence.

- Purfield, M., Finger, M.H., Ongley, M.K., Baduel, M.B., Castellanos, C., Pierre, M.G., Stepanyan V & Roos, M.E. (2018). Opportunity for All: Promoting Growth and Inclusiveness in the Middle East and North Africa. International Monetary Fund.

- Ramady, M.A. (2005). Saudi Arabia and the gulf cooperation council (GCC). The Saudi Arabian Economy: Policies, Achievements and Challenges, 417-452.

- Richards, M.M., Zellweger, T.M., & Englisch, P. (2016). Family business philanthropy Creating lasting impact through values and legacy.

- Rodríguez?Ariza, L., Cuadrado?Ballesteros, B., Martínez?Ferrero, J., & García?Sánchez, I.M. (2017). The role of female directors in promoting CSR practices: An international comparison between family and non?family businesses. Business Ethics: A European Review, 26(2), 162-174.

- Santiago, A., Pandey, S., & Manalac, M.T. (2019). Family presence, family firm reputation and perceived financial performance: Empirical evidence from the Philippines. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 10(1), 49-56.

- SmallBusiness. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://smallbusiness.ng/why-do-family-businesses-fail/

- Smith, S.C. (2019). Britain and the Arab Gulf after Empire: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, 1971-1981. Routledge.

- Soto Merino, R. (2015). Fiscal institutions in a rentier state-the case of the United Arab Emirates.

- Ulrichsen, K.C. (2016). The Gulf states in international political economy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zahra, S.A., & Sharma, P. (2004). Family business research: A strategic reflection. Family Business Review, 17(4), 331-346.