Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Family Firms in the Face of Social and Economic Inequalities in Latin America

Karina Concepción González Herrera, Metropolitan Technological University

Andrés Miguel Pereyra Chan, National Technological Institute of Mexico, Technological Institute of Mérida

Stephany Giselle Martín Sánchez, National Technological Institute of Mexico, Technological Institute of Mérida

Jorge Carlos Castillo Canto, National Technological Institute of Mexico, Technological Institute of Mérida

Keywords:

Family Firms, Social Inequalities, Economic Inequalities, Latin America

JEL Codes:

D29; F29; H31

Abstract

The Latin American region is one of the territories in the world that has historically been affected by the phenomenon of social and economic inequality. The impact of this problem seriously affects organizations, considering that they are in a constant struggle to be competitive, innovative and profitable in the environment where they operate. The objective of this article is to analyze the inequality generated in social and economic terms in family businesses in Latin America, addressing the emergence of their study. Among the main findings detected is the profile of family firms, as well as the dynamics implemented in terms of policies and programs, implemented by the governments of the nations of Latin America to confront.

Introduction

Inequality in Latin America stem from the construction of organizations that gave rise to social and economic dynamics during the Colonial Period, triggering the presence of a stratified society centered on the establishment of a dominance acquired by certain social classes, overlapping other strata (Yasunaga, 2020). The study of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2019) exposes inequality as the result of combining the productive systems and the privileges that benefits a certain social stratum, which has been maintained in Latin American societies throughout history despite the recurrent social and economic growth, becoming one of the main challenges to combat unsustainable development, poverty and the non-fulfillment of the human rights.

Latin America is considered the most unequal territory in the world, especially when it comes to income and wealth. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB, 2020), states that, in this region, 10% of the upper class receives 22 times more of the national income than the poorest 10%, in addition, 1% of the wealthiest has 21% of the total income of Latin America’s economy. The ECLAC (2019) declares that the effects of inequality are evidenced in the poverty of a nation, recognizing it as a central issue to achieve sustainable development in Latin American countries, which made it clear that the income inequality has a negative impact on productivity increase, innovation management and, consequently, on economic growth; unfortunately, Latin America keeps a decrease from 0.538 to 0.477 from 2002 to 2014, and subsequently to 0.469 in 2017, reflecting a slow reduction in income inequality of 0.9% per year.

The increasing levels of poverty and extreme poverty represent an important challenge for Latin American countries, therefore, public policies and initiatives must consider the implications of this situation that so aggravates the region; also, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2020a) estimates that 30.1% of the Latin American population, or 185 million people, is within the poverty stratification, specifying that 10.7% of this stratum, or 66 million people, is classified as extreme poverty; in addition, poverty in 2018 increased 2.3% compared to 2014, indicating a total of 21 million people who migrated to poverty levels; and, in terms of extreme poverty, during the 2014-2018 period there was an increase of 2.9%, or approximately 20 million people.

According to the IDB (2020), inequality has expanded its effects to the educational sphere. Children from wealthy families or those growing up in a higher-income family are likely to have a better educational outcome, showing a more favorable academic performance in their cognitive, linguistic and socioemotional development, which leads to a greater probability of entering the labor market. Latin America has not had the capacity to transform the education system into one that represents equal opportunities, given that, to have a successful educational outcome, the presence of a good environment and disposable income in households is required; and, as well as the reflection of educational inequality in Latin America, a quality segmentation in the educational offer can be visualized (Trucco, 2014).

The gender gap is easily seen in Latin America, since female’s labor force participation rate is lower in the zone, something that limits their opportunities to the informal employment with lower-pay; adding on, most women do not participate in top corporate executive positions. To counteract the gender inequality in the region, it is essential to create public policies that allows women to progress in the labor market, and to improve the labor performance of both, men and women, so the productivity of the area increases; thus, closing gender gaps, mainly in labor force participation, would result in a gain of 26% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on a global scale (Marchionni & Gasparini; Edo, 2018).

Finally, its effects have expanded to the ethnic and racial sphere, having the culture of privilege as its key element, which influences the behavior of societies and the Latin American economy, producing behavioral rules and distortions in the region's society (ECLAC, 2020a). In Mexico, for instance, those considered as white or mestizos with light skin tones have greater access to professional growth and, therefore, more possibilities of getting a well-paid job, due to their level of education and competence development (Solís et al., 2019).

Furthermore, according to the United Nations (UN, 2020), Latin America is one of the regions most affected by the epidemic disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), which, along with a fragile social protection and fragmented health systems, shows a clear inequality. Regional valuation manifests a 9.1% fall in GDP, increasing the numbers in poverty and extreme poverty to 45 and 28 million people, respectively. As might be expected, Latin America has suffered several crises in the political and social context; it is contemplated that the increase of inequality, discrimination and exclusion will affect the management of democracy, causing serious damage to human rights, so it is essential to address the situation to reduce or abolish any negative impacts or conflictive social movements.

According to the Oxfam Mexico report (2021), the COVID-19 epidemic will lead to negative consequences in terms of inequality in the Latin American region, since it is estimated that there will be an increase in income, wealth, gender, and racial inequality by 87%, 78%, 56% and 66% each. The phenomenon of equality will be a determining factor in controlling the effects of the pandemic in Latin America, as it provides sustaining income and aggregate demand schemes to achieve a greater level of social inclusion of the marginalized groups; therefore, for the reactivation of its economy, equality is fundamental for the impulse of growth and productivity, that could only be achieved through the delivery of quality education and health care to all. From a gender perspective, equality for women and empowerment actions are part of the solution, taking into account that the epidemic has affected female workers significantly, forcing many of them to be part of the informal work force, in addition to continue the housework (UN, 2020).

In the frame of reference of inequality in Latin America, family firms represent an economic agent that contributes substantially to the economic growth and welfare. It is estimated that they represent between 50% and 70% of the GDP in the territory, which represents 70% of Latin American establishments, producing over 50% of the income and employed personnel (San Martín & Durán, 2017), understanding the significant role family firm’s play in the regional economy.

Among the basics involving social and economic inequality, as well as the intervention of this phenomenon in Latin America, the objective of this article is to identify the difficulties family firms face in terms of social and economic inequality, as its dynamics are key components for Latin American socioeconomic growth and development.

Theoretical Framework

The Evolution of Management Models: Theoretical Analysis

The economic, social and cultural disparities that can be found in comparison to developed countries, has evidenced the remarkable tendencies that Latin American countries have towards management sciences that were originated in Western Europe and the United States, revealing a position of replicability and extemporaneous recognition of work models that have evolved according to the needs of business management, having an impact on the countries to a certain degree, which is stated by the presence or absence of contextual factors that interfere in its functionality (Wahrlich, 1978). The industrial revolution was a key turning point in the evolution of management, which leads to the emergence of new management theories and models that brought a process of organizational restructuring (García-Olivares & Beitia, 2019), heading to its beginning in the 20th century as a response to business obstacles in an era of constant transformation, portraying a turning point to the empirical approach, evolving into a much more objective method (Beltrán & López, 2018). According to the theoretical analysis conducted by Almanza, et al., (2018); Beltrán & López (2018); Hernández (2011); López, et al., (2006); Viloria & Luciani (2015), different types of management approaches are detected: classical, humanistic, structuralist and modern.

Classical management theory built the basis of management that improved organizational effectiveness by directing all efforts towards the successful goal fulfillment through the principles of dominance, command and influence over its associates (Beltrán & López, 2018; Viloria & Luciani, 2015). This management model was developed by Taylor (1911), who applied methodical procedures to pay attention to workers’ inconveniences, improving the measurement of employee productivity and the relationship of subordination; & Fayol (1916), who emphasized the significance of the employer as a regulatory leader through the creation of optimal communication channels that could help to incorporate the perception of human resources, and successfully accomplish the institutional goals.

Humanistic management is an approach that provides a solution to the productivity deficiencies caused by the informal relationships in the companies, sorting out the simplicity of the classical theories to improve the performance management method, while satisfying the essential needs of employees (Beltran & Lopez, 2018; Viloria & Luciani, 2015). This work model was developed by Tead, who standardized management through an equal appreciation of employees’ nature and behaviors, leading their actions towards the achievement of a shared vision (Beltrán & López, 2018); Foller, who rethought the concept of authority as a consequence of the internal functioning of the organization, emphasizing the importance of each human resource exercising a certain level of authority for the fulfillment of their role (Beltrán & López, 2018; Mayo,1945), who detected the relevance of psychological factors within the work environment, perceiving new behaviors in the presence or adjustment of features such as space, working hours, economic incentives, among others; Chester Barnard, who added the external context that surrounds companies to the interrelationships exposed by Mayo, recognizing the value of stakeholders in the companies’ productivity and profitability, adjusting their organizational management to the external dynamics to maintain the stability that enables the endurance of businesses (Beltrán & López, 2018; Maslow, 1943), who pointed out the stimulation of employees’ motivation as a way to achieve a positive working environment through his five-stage model: physiological needs, safety needs, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization.

Over the course of time, the structuralist theory was created featuring Weber's bureaucratic theory, solving the imbalance shown in the classical and humanistic work models, (Beltrán & López, 2018; Viloria & Luciani, 2015). The approach of this management model was based on process rigidity to run a business in the best way possible, leading to the assignment of roles, responsibilities, a hierarchical structure, rules and regulations (Beltrán & López, 2018).

Lastly, the modern management theory arose as a way to support businesses operativity in the presence of an uncontrolled and competitive environment, forcing the evolution of traditional management models: Just in time method, benchmarking, Total Quality Management (TQM), empowerment, downsizing, coaching, Balanced Scorecard, Theory of Constraints (TOC), reengineering, joint venture, among others (Beltrán & López, 2018; López et al., 2006); in addition, the incessant technological evolution demands competitive advantages such as digital transformation, business automation and innovation to potentiate its operability (Gómez, 2019).

The organizational change and the process of transition management turns out to be advantageous for the companies’ growth and stability, allowing the development of management sciences via distinct theories, highlighting the social and economic benefits (Table 1) that each of these approaches brought with them, improving the situation of the company and its subordinates.

| Table 1 Analysis of the Social and Economic Benefits of the Management Models |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model | Social benefits | Economic benefits |

| Classical Approach (Fayol, 1916; Taylor, 1911) | 1) The employees are not view as productivity tools anymore, reducing working hours and levels of exhaustion. 2) Wage increase and fair compensation, introducing productivity-based incentives and bonuses. 3) Objective selection, assigning roles according to skills, increasing work efficiency levels through job specialization and training. | 1) The reconstruction of productivity systems increased efficiency by encouraging collaborative work over autonomy.2) Employees' remuneration improves, increasing business productivity. 3) The company's resources are managed correctly, increasing employee's skills and reducing production costs. |

| Humanistic Approach (Beltrán & López, 2018; Maslow, 1943; Mayo, 1945; Tead, 2012) | 1) Employees are valuable resources, respecting their personal growth, well-being and dignity. 2) Development of effective work relationships. 3) Employees are involved in the decision-making process, valuing their contribution as key members of the organization. 4) Improved physical work environment, providing greater comfort to ensure the employees' safety. | 1) Employee's satisfaction reflects in the company's productivity growth and, therefore, in its economic efficiency. 2) Increase of the employees' commitment, achieving the company's goals. |

| Structuralist Approach (Beltrán & López, 2018) | 1) Sectioning the company's activities allows the employees to prepare and specialize in their roles. 2) The inflexible structure reduces conflicts that may arise in the organization, through the process standardization and the punctual role delegation. | 1) The role delegation increases the company's efficiency, since the employees fully understand their role and assumes them with a high level of responsibility. 2) The employees' selection is based on the job requirements, increasing their efficiency. |

| Modern Approach (Beltrán & López, 2018; Gómez, 2019; López et al., 2006) | 1) Increased participation of employees in the decision-making process, giving them a certain degree of authority. 2) Impulses the development of corporate culture, increasing the willingness of employees, giving them a sense of belonging. 3) Satisfies the employees' needs to a great extent, promoting their personal and professional growth. | 1) Use management modern tools to reduce the impact of market fluctuations, improving the rocedures' effectivenes, reducing costs, downtime and wastage, developing higher quality products and services, and improving delivery times.2) Reducing uncertainty of market fluctuations. 3) Increases the company's market share and, therefore, the corporate performance and it's competitive positioning. |

The importance of management models lies in the responses that directors show through their business administration, finding out opportunities that these models evolution brings with them to be a source of added value within the company, improving their economic performance while assessing the consequences of their actions on their immediate social environment and on their stakeholders. Adjustment is fundamental for the survival of companies which, in a family context, as will be explained in the following sections, becomes more complex due to family involvement.

Work Schemes Adaptations to the Family Context: Theoretical Analysis

The family firm, as an object of study, emerged in the early 1970s as a way to observe its composition and the impact of family dynamics on business development, highlighting the dissimilarities with non-family firms (De la Garza-Ramos et al., 2012). In recent decades, there has been a notable increase in the number of research studies in this field of study, making theme a relevant topic in business management; however, the lack of a generalized conception has diminished its growth as a discipline of knowledge (Benavides et al., 2011). The non-existent of a theory that unifies its conception, leads to the presence of infinite interpretations of what a family firm is (Table 2), issuing the first setback in its analysis (Belausteguigoitia, 2017).

Certainly, the most evident method to differentiate a family firm from a non-family firm is the intervention of family members in the business dynamics; nevertheless, this remains as an incomplete concept (Belausteguigoitia, 2017; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, 2010). It is undeniable that the family nucleus takes possession of the business domain since the shares are predominantly owned by them, and the family members are associated in directive and managerial positions; despite this, the roles that, to a lesser degree, are impaired by the family bond should not be neglected (Leach, 1993). Consequently, the study of family firms is connected to the particularities that affect them, differing from the circumstances of non-family firms. as shows in Table 2.

| Table 2 Comparative Analysis of Family Firm Definitions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Definition structure | ||||

| Family | Domain | Direction | Management | Succession | |

| Barnes and Hershon (1976) | X | X | X | ||

| Leach (1993) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Tagiuri and Davis (1996) | X | X | X | ||

| Ward and Dolan (1998) | X | X | X | ||

| Chua, Chrismas and Sharma (1999) | X | X | X | X | |

| Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2003) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Vélez, Holguín, De la Hoz, Durán and Gutiérrez (2008) | X | X | X | X | |

| Trevinyo-Rodríguez (2010) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Belausteguigoitia (2017) | X | X | X | ||

It is fundamental to understand that the property of family firms is centered around its intervention in the ownership, direction, management and succession of the business, and, therefore, on their institutional goals (Chua et al., 1999). Notoriously, the theoretical analysis of family firms has yet to introduce a generalized conception of the term, but the comparative analysis shows the presence of three overlapping dimensions: ownership, business and family. Based on the above, models have been proposed to understand their constitution, management and behavior from a scientific and administrative approach. Among the existing theories, those that have stood out through the process of literary dissemination are supported by the flowing approaches: (1) the general theory of systems; (2) in evolutionary approaches; and (3) in strategic management (Molina et al., 2016).

The first approach incorporates the three-circle model (Tagiuri & Davis, 1982), which points out the existing overlaps of the three dimensions that integrates the family firms according to presence of conflicts and their imbalance; the holistic overview of the family firms (Donckels & Frölich, 1991), which incorporates the mutual dependence between the organization and the endogenous and exogenous variables that influences its immediate environment; and the five-circle model (Amat, 2004), which restructures the three-circle model, splitting the business dimension in two directions: management and business, adding, also, a complementary dimension: succession. The second approach incorporates the three-dimensional evolutionary model (Gersick et al., 1997), which views the ownership, business and family dimensions as three-dimensional axles, making possible the longitudinal study of its performance. The third approach incorporates the model of Sharma, et al., (1997), which identifies the family firm by its organizational outcome resulting from the involvement of the family members in the business dynamics; and the integrative model of Ussman (2001), as cited in Molina, et al., (2016), which is based on the family firm’s continuous learning process as an institution that takes permanent reciprocal action between the family dimension and its surroundings, creating strategies from the analysis of its opportunity areas and ways of improvement.

The work schemes adapted for the study of the family context are attributed by the representative and complementary contributions that strengthen their theoretical approach. Clearly, family firms drag more complicated situations than those that do not share this trait, which tends to their discontinuity (Bolio & Aparicio, 2019; San Martín & Durán, 2017; Tagiuri & Davis, 1996; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, 2010); this is due to the implications of the family in the business dynamics, disfavoring the interaction of its members and, therefore, provoking disputes that damage their continuity. To repair this situation, Arenas; Rico (2014); Belausteguigoitia (2017); Trevinyo-Rodríguez (2010), recommend that family firms indulge in the disintegration of the family-business dimensions through the resolution of conflicts that induce the rupture of their subsystems, contributing to the dissemination of a work environment that will benefit the relationships of the family members and outsiders.

Inequalities in Latin American Family Firms

Family firms in Latin America produce a large portion of the region's wealth. On top of that, they are organizations that systematically participate in the creation of the social, political, economic and cultural network, developing Latin American emerging nations’ economic growth, possessing multifunctionality and flexibility features (Herrera et al., 2017). Companies are stratified according to their size; specifically, in the case of Mexico, 57%, 29% and 11% are stratified as Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), respectively (San Martín & Durán, 2017).

The creation and development of the family firms also faces the phenomenon of inequality due to the uncertainty in Latin America, caused by the instability in the economic and political sphere (Molina & Sanchez, 2016). According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2019), family MSMEs have productivity deficiencies in comparison with more capital-intense companies, showing a low performance since they only produce a quarter of the production of the entire region. On the other hand, the inequality experienced within the family business, especially those stratified as Latin American MSMEs, is due to various obstacles they have to face to continue developing, such as the inequality gap, lack of access to finance, lack of job specialization, and limited access to technology (Molina & Sanchez, 2016); likewise, Dini, Rovira & Stumpo (2014) evidence the lack of funding and the lack of skilled human resources as those with greater relevance. Competitiveness in Latin American family firms is essential in order not to survive in the market and avoid growth in the economic inequality gap, so the obstacles they face in their internal structure are the longevity, the family ownership that weakens the hierarchy in its structure, the succession and control of the business, and finally, the lack of an independent corporate governance, because the family culture has an important weight in the decision-making process (Ramirez et al., 2018).

Methods

This study exposes the analysis and theoretical review of latent social and economic inequalities in family firms, especially in Latin America and Mexico, with a longitudinal perspective that includes the current considerations of the pandemic, which represents one of the determining points of the increase in inequality. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2020b) states that the economic impacts of the Coronavirus disease in this area can be noticed in the reduction of economic activity with trading partners, the collapse of prices in primary products, the brake on the value stream, the decrease in tourism demand and the negative response of the international financial systems. Facing this economic crisis, Latin American national governments established regulatory policies with the purpose of providing support to those in need, boosting productive development to create optimal conditions in the market that potentializes their economic growth and strengthen their competitiveness (Ferraro & Rojo, 2018).

The negative effects of the epidemic are amplified by virtue of the particularities of the contextual of each country in Latin America. As stated by Blackman, et al., (2020), a starting point lies in the analysis of the fiscal fragility, given that Latin America is in a tight spot for the 2008 recession, demonstrating its fiscal inability to increase expenditures in comparison to developed countries; ergo, in response to this economic crisis, the construction of national policies is focused on avoiding the collapse of the financial system, protecting employment and neutralizing the increases of inform economy, preventing the closure of a large number of organizations liquidity risks, and speeding up the processes of economic reactivation once the health crisis has been overcome. In addition, the UN (2020) presents a series of recommendations for Latin America to face this challenge in the short term: create macroeconomic policies focused on households and individual’s consumption and wealth; develop national systems to promote the redistribution of unpaid work and the presence of women in the labor market; make more progressive tax system; promote financial stability by increasing participation in the currencies market and capital management; and support MSMEs through liquidity injection and access to finance; also, for economic recovery, it recommends establishing spending limit, encouraging private sector investment, combating tax evasion and avoidance, increasing public investment to address the health crisis, promoting the sustainable development of nations, creating technology and industry policies, and creating policies that promote the inclusion and labor force participation of women and young people, in addition to remove gender inequality. Based on this, and according to the International Labor Organization (ILO, 2020), institutional, economic and political agents in Latin America created policies and programs that strengthen the business sector in the most important nations of Latin America to develop conditions that could generate economic growth and opportunities to achieve their permanence, focusing on four strategic axles: financing; tax measures and payment deferral; employment protection; and digital tools and job training (Table 3).

| Table 3 Policies and Programs to Support the Business Sector in Latin America |

||

|---|---|---|

| Financial access policies and programs | ||

| Chile | Fogape and Fogain guarantees | Sources of funding through the financial system. |

| NBFIs financing | Liquity injection and State guarantees. | |

| Tourism reactivation/Sercotec | Economic reactivation for digitalized firms via subsidies. | |

| PAR Impulsa 2020 | Productive reactivation for digitalized firms via subsidies. | |

| CMF Chile measures | Loose credit regulations. | |

| Re-entrepreneurship facilities | Strengthen renegotiations and reducing settlement costs. | |

| Colombia | United for Colombia | Grant guarantees to insure credits to financial intermediaries in the face of economic challenges caused by COVID-19. |

| Bancoldex special lines | Sources of funding at less aggressive interest rates in the face of economic challenges caused by COVID-19. | |

| Costa Rica | SBD’s action plan | Sources of funding and creates payment facilities. |

| Loan renegotiation | Sources of funding and loan renegotiation. | |

| Working capital loan | Sources of funding for workforce expenses, suppliers or inventories, for their continuity and employment protection. | |

| Mexico | Partial or total deferral of payments | Defer payments when the main source of income is affected. |

| Tandas para el Bienestar | Sources of microfunding for medium, high or very high marginalization areas with a high rate of violence to consolidate their productive activities. | |

| Solidatiry support “a la palabra” | Sources of funding for SMEs’ workforce expenses during the sanitary emergency. | |

| Development banking: I+H | Tourist mexican companies’ economic reactivation. | |

| IDB Invest CMN loans | Sources of funding to pro productive chains (MSMEs). | |

| Fiscal support and tax deferral policies and programs | ||

| Chile | Refund, extension and suspension | Tax payments and health crisis expenses exemptions and refunds. |

| Three months postponement of IVA | ||

| Sanitary disbursements | ||

| First category tax rebate | Reduce taxation and instant depreciation. | |

| Investment incentives | ||

| Colom- Bia | Tax exemptions | Reduce tax burden of certain sectors (IVA and consumption). |

| ISR tax deferral | Defer tax obligations, reducing the tax burden. | |

| Refunds and/or offsets | Advance the delivery of balances in favor of taxpayers. | |

| Costa Rica | Tax relief law (COVID-19) | Make tax collection more flexible. |

| IVA moratorium and reduction | Progressively increase IVA on tourism companies. | |

| Reduced BMC | Reduce 25% of the BMC for labor payrolls. | |

| Mexi- Co | Payment facilities and deferral of employer's contributions | Grant extensions for workers' contributions to SMEs. |

| Employment and social protection policies and programs | ||

| Chile | Employment protection law | Extraordinary access to unemployment insurance and solidarity fund. |

| Employment subsidy | Support in the rehiring of suspended workers and hiring of new workers. | |

| Colom- Bia | Formal employment support program | Support up to 40% of the salary reflected in the payroll. |

| Bonus payment support program | Support up to 50% of the semi-annual bonus payment. | |

| Costa Rica | Suspension and temporary reduction of working hours and salaries | Prevent significant reduction of employment, modifying labor contracts on a temporary basis. |

| Mexi-Co | No employment or social protection initiatives were developed in Mexico. | |

| Innovation, digital tools and employee training policies and programs | ||

| Chile | Digitize your SME | Promote training, advertising and e-commerce. |

| All for SMEs | Increase participation in the Internet through online sales. | |

| Support me | Marketplace platform. | |

| Community C | Digitalization of organizations. | |

| Guide of tools for tourism | Platform of digital tools for tourism. | |

| Consulting and training | Free courses, general and specialized training. | |

| Compra Ágil Portal | E-commerce platform for government purchases. | |

| Buy what's ours: platform | Incite competition and productivity with digital tools. | |

| Colombia | Buy what's ours: distinctive seal | Promote sales in the domestic market in domestic products. |

| Buy ours: barcodes | Obtain bar codes and identification for products. | |

| Buy ours: SoftWhere | Platform to establish connections with developers. | |

| Buy Ours: In My Business | Enhance e-commerce and door-to-door sales. | |

| Buy Ours: StoreON | Create connections with the main Marketplaces in the world. | |

| Costa Rica | Marketing platforms | Publicize and support private sector websites. |

| Tips for SMEs | Counteract COVID effects through business training. | |

| Alivio Program | Support with business consulting and non-reimbursable funds. | |

| Mexico | MSMEs MX Platform | Advise and train in sales, export and digitalization. |

| e-Business Roundtables | Gather supply and demand for products or services. | |

| Solidarity Market | Establish connections between clients and businesses. | |

Latin American governments have analyzed the problems caused by COVID-19; therefore, the policies and programs seek to rescue and reactivate the economic systems of their countries. Particularly, there are no policies or programs aimed at family firms; however, these are part of the business sector of each region integrated to Latin America, so these initiatives also contemplate these firms so that they can receive the benefits, obtaining better tools to face the economic and social challenges that this epidemic has brought.

Results

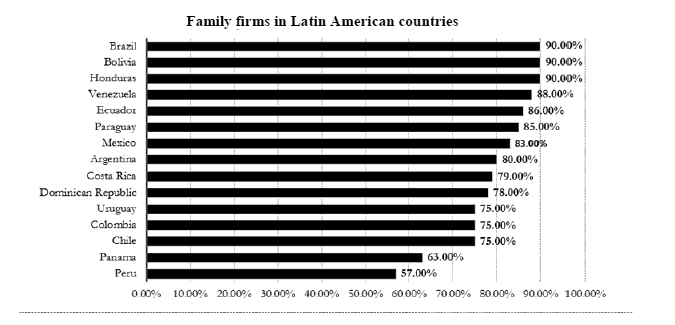

In view of the essence that characterizes family firms, the main objective of this research is to diagnose the current situation of these companies in Latin America, as well as the conditions of social and economic inequality that deteriorate their permanence in the market; ergo, the percentage of participation of those residing in Latin America was obtaining through analytic approximation by nation (Figure 1).

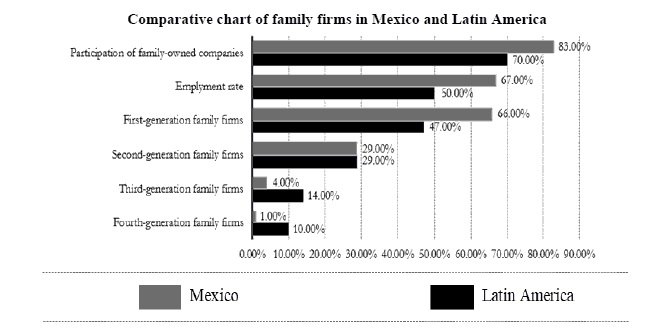

It is known that the Latin American region comprises a territoriality of more than 20 countries, which translates into the reciprocal connection of their socioeconomic environments that, in spite of this, are distant in complex circumstances. This statement reveals the disadvantage in the situational analysis of family firms in a region such as Latin America, in contrast with each of its countries that make it up, such as Mexico, highlighting the obvious differences and similarities arising from one region to another (Figure 2)

Figure 1: Family-Owned Firms Participation Per Latin American Country

Source: Authors' Compilation based on texts by Camara Costarricense de Empresas Familiares (CACEF, 2014); Camino-Mogro and Bermudez-Barrezueta (2018); Dávalos yand Ramírez (2019); Echaiz (2010); Molina, et al., (2017); Munguía (2015); San Martín & Durán (2017); Tapies (2011).

Figure 2: Comparison of Family-Owned Companies in Mexico and Latin America

Source: Authors' Compilation based on texts by Davis (2006); San-Martín & Durán (2017) ; Ramírez, et al., (2018).

These firms in Latin America make up 70% of the business sector (Davis, 2006). The different reports show that Brazil, Bolivia, Honduras, Venezuela and Ecuador are the countries with the highest involvement of family firms, while countries such as Peru, Chile and Panama have the lowest participation rates. Likewise, as reflected in the chart, 83% of the companies in Mexico are family-run businesses; in which Nayarit, Yucatan and Nuevo Leon have a culminating involvement of 97%, 94% and 93% respectively, while Quintana Roo, Campeche and Tabasco hold a lower involvement with 60%, 63% and 65% respectively (San Martín & Durán, 2017).

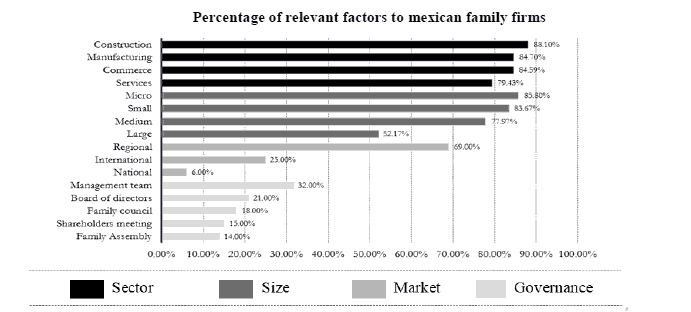

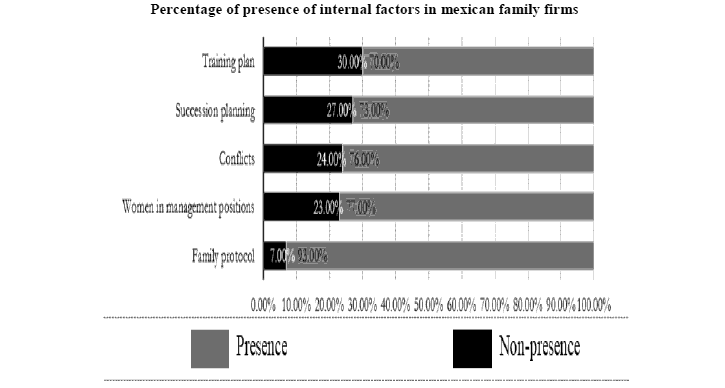

The permanence of family firms differs substantially in the Latin American region compared to the Mexican region. As shown in Figure 2, both demonstrate predominant numbers in the first generation, however, it is clear that Mexican family firms are more susceptible to failure in the transfer stages from the second to the third generation, and from the third to the fourth generation. In addition, Mexican family firms have greater possibilities of accessing a source of finance compared to family firms in other Latin American countries; likewise, they have greater opportunity to acquire a professional and commercial infrastructure that brings on the benefits desired by family firms and, lastly, there is a characteristic in common with these types of business in Latin America, which is the corporate governance lack of independence, which is reflected in the operation and business development (Ramírez et al., 2018). As Figure 3 shows, 88% of family firms belong to the construction industry, 86% are stratified as microbusinesses, 69% are regionally consolidated, and 32% integrates a management team as a governance body; on the other hand, as Figure 4 indicates, the presence of internal factors contributes to competitiveness and, consequently, to its continuity, but unfortunately, in Mexico their levels are extremely low, since only 30% have a training plan that ensures the training of its members, 27% generated a succession plan that promotes the correct transfer of the company, 23% have women participating in management positions, 7% created their family protocol to determine the actions of family members in specific situations, and only 24% have been damaged by the presence of conflicts (San Martín & Durán, 2017).

Figure 3: Mexican Family Firms Statistics

Source: Authors' Compilation based on texts by San Martín and Durán (2017).

Figure 4: Presence of Internal in Mexican Family Firms

Source: Authors' Compilation based on texts by San Martín & Durán (2017).

Last of all, channeling the results to inequality issues, public policies are joint efforts aimed to raise the socioeconomic development of Latin America's countries, but their limited orientation has kept the disparity gap at alarming rates. Business stimulus programs are focused on giving priority attention to families in circumstances of poverty or residing in highly marginalized communities, segregating those families with ethnic and racial characteristics, which represent one of the main obstacles to social mobility; in addition to this, support programs oriented towards the delivery of economic resources neglects the needs of training and competence development that truly orients the resources to the growth of the company and its members, and thus its object seems to be focused on traditional assistance; such is the case of women as subjects of vulnerability with little preponderance in the governmental agenda of the Latin American region (Ordaz et al., 2010), a reality that can be observed in chart 4. Likewise, there is an interconnection between the stratification of the family firm and its longevity, being that, the larger the size, the more long-lasting it is (San-Martín & Durán, 2017), that means that permanence is determined by the size it obtains over the years, being possible through its institutionalization; however, this is obstructed by the low relevance that the owners give to it and the insufficiency of public policies that favor its situation and that of its members. At the same time, the pandemic has hindered the position of economic inequality in family firms with the suspension of non-essential economic activities to reduce the contagion rate, conditioning the approval of the sale of products and provision of services of specific sectors such as construction, manufacturing, tourism, entertainment and recreation, real estate agents, corporate activities, educational, among others (Murillo et al., 2020), causing the imminent closure of a large number of MSMEs. The political inclination regarding the socioeconomic situation of family firms in Latin American countries highlights the lack of programs aimed at making visible the importance that companies of this nature have on their macroeconomic context.

Conclusion

The influence that the family dimension sets on Latin American family firms astonishes, hence the importance of the need to adjust the demands of the family and the business to stabilizing their systems. However, the owner’s good will is not enough; they need to ensure their permanence in a highly competitive market through concrete strategic axles aimed at reducing damages, strengthening their structure and taking advantage of the opportunities presented by their surroundings.

First of all, the family firm must be valued, perceiving the internal context in which it operates, through axles that determine the opportunities for improvement in order to ensure its continuity: (1) dividing the business and family dimensions trough the differentiation of the role that each member must play, and the management of economic operations and the enjoyment of capital assets; (2) programming and carrying out the succession process and its professionalization, based on the solidification and establishment of governance bodies; (3) promoting a healthy family coexistence in the business environment through diligent attention of disputes; and (4) orienting the vision towards a profitable future to successfully achieve the business, family and personal goals (Bolio & Aparicio, 2019). Secondly, complement their professionalization and training by allowing entrepreneurial progress and competitiveness promoting by (1) implementing training programs for family members; (2) transferring knowledge to future generations; (3) selecting a profession similar to the skills and competencies of future members; and (4) requiring a minimum degree of competencies to integrate family and non-family members into the company (Santamaría & Chicaiza, 2020). Thirdly, the owners must be willing to receive external assistance to guide the entrepreneurial family to (1) detect its position in regard to its dimensions; (2) consider threats as challenges, not as misfortunes; (3) recognize the members who are willing to correct the situation they face, no matter how difficult; and (4) follow-up actions, evaluating their effectiveness (Habbershon et al., 2009). Lastly, the proposal and implementation of multiple public policies to reduce the discontinuation of family firms, which represent a substantial portion of the business sector in Latin America and the world. The mortality levels of family firms in Latin America are worrisome, so policies have been strengthened to encourage their participation, institutionalization and continuity (Munguía, 2015); consequently, proposals are presented to influence public policy, striving for their healthy development and growth, thus reducing the social and economic inequality gap (Table 4).

| Table 4 Public Policy Proposal For Latin American Family Firms |

||

|---|---|---|

| Proposal description | Related institutions | |

| Empower-ment of women | Reinforce entrepreneurial learning and boost its economic strength; promote child care spaces for single mothers and enable their full development. | Secretariat of Economy, Secretariat of Women, Secretariat of Welfare (Mexico); Foundation for Women's Promotion and Development (Chile); ECLAC (region). |

| Corporate sustaina-bility | Promote actions to care for the environment, supporting the abolition of discriminatory practices in employment and occupation. | Mexican Center for Philanthropy, AliaRSE (Mexico); CEADS (Argentina); CEBDS (Brasil); Consejo Nacional Venezolano para el Desarrollo Sostenible (Venezuela); ECLAC (region); among others. |

| Financial education and inclusion | Strengthen the financial planning of family MSMEs in order to have the knowledge and tools to manage business finances more effectively. | Bank of Mexico, Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, Mexican Stock Exchange, Secretariat of Economy (Mexico); Fondo de Instituciones Financieras de Colombia (Colombia); OECD, Development Bank of Latin America (region). |

| Latin American connectivity | Establish an international connection in Latin American family firms, creating opportunities for commercial exchange and knowledge transfer, building a business connection that contributes to their growth and evolution. | Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Secretaría de Fomento Económico y Trabajo, Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (Mexico); Servicio de Cooperación Técnica (Chile); Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism (Colombia); National MSE Commission (El Salvador); ECLAC, CAF (region). |

| My Accoun-tant | Establish an accountant to assist in the business accounting, tax calculation, and fiscal advising. | Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, Tax Administration Service, Secretariat of Economy (Mexico); IDB (region). |

| Towards professiona-lization | Analyze their level of professionalization to strengthen their internal structure, improve their planning, conflict resolution, continuity, family protocol and corporate governance. | Instituto de la Empresa Familiar Latinoamericana, Corporate Governance in Latin America (region). |

| Provisioning | Establish commercial agreements between large consolidated family organizations with significant purchasing power, and family MSMEs, increasing their income and competencies. | Secretariat of Economy; Secretaría de Fomento Económico y Trabajo, Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, Small Business Development Centers (Mexico); Andean Development Corporation, ECLAC (region). |

| My company, my family, my workforce | Support through subsidies the payment of social security and housing fund contributions for a period of four months, reducing payroll costs, investing them in their operation. | National Employment Service, Secretariat of Welfare, Secretaría de Fomento Económico y Trabajo (Mexico); Andean Development Corporation, ECLAC, IDB (region). |

Family firms are established businesses that, although they have an unshakable role in the Latin American economy, their requirements evolve over time. According to Bermejo (2015) the challenges they will face in the present and in the future are focused on separating business and family matters; determining the role of the family members according to their skills and competencies; progressing gradually, adopting digital, technological and methodological tools that increase their competitiveness; conserving a holistic vision; and accepting external support from consultants or mediators that bring value to the organization. Therefore, it is essential that family firms understand the factors that need to be developed, leading to the implementation of strategies and constant innovations; likewise, future research is needed to compare Latin American and foreign family firms, in order to achieve the transfer of new dynamics, models and methodologies that stimulate the social economic structure (Perdomo et al., 2020). Finally, Bolio & Aparicio (2019) expose that family-owned businesses possess what is necessary to achieve their permanence, however, this is not taken advantage of by their owners and family members; for example, of the totality of the Mexican family firms, only 30% consider that they have a relevant degree of progress, while 58% consider that they need to improve several internal aspects, and 12% consider that they are in an imminent and not very encouraging risk that, in conjunction with the lack of business development programs and policies, a hardly promising future is observed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Almanza, R., Calderón, P., & Vargas-Hernández, J. (2018). Classical theories of organizations and Gung Ho. Scientific Magazine "Vision of the Future", 22(1), 1-18.

- Amat, J. (2004). The continuity of the family business. Barcelona, Management 2000 Editions.

- Arenas, H., & Rico, D. (2014). The family business, protocol and family succession. General Studies, 30 (132), 252-258.

- Busso, M., & Messina, J. (2020). The crisis of inequality: Latin America and the Caribbean at the crossroads. United States: Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

- Barnes, L.B., & Hershon, S.A. (1994). Transferring power in the family business. Family Business Review, 7 (4), 377–392.

- Belausteguigoitia, I. (2017). Family businesses: Dynamics, balance and consolidation. Mexico City: McGraw Hill.

- Beltrán, J., & López, J. (2018). Evolution of the Administration. Medellín: Luis Amigó Catholic University Editorial Fund.

- Benavides, C., Guzmán, V., & Quintana, C. (2011). Evolution of the literature on family business as a scientific discipline. Notebooks on Economics and Business Management, 14(2), 78-90.

- Bermejo, M. (2015). Latino family businesses: More government, better businesses. Madrid: DI.

- Blackman, A., Ibáñez, A., Izquierdo, A., Keefer, P., Moreira, M., Schady, N., & Serebrisky, T. (2020). Public policy against Covid-19: Recommendations for Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington: IDB.

- Bolio, A., & Aparicio, R. (2019). Level of progress of family businesses to achieve their continuity and harmony. Report 2019.

- Costa Rican Chamber of Family Businesses (2014). Results of the second study on Costa Rican family businesses, family council and family protocol: practical approach. Texas: Exaudi Family Business Consulting.

- Camino-Mogro, S., & Bermudez-Barrezueta, N. (2018). Family businesses in Ecuador: Definition and methodological application. X-Economic Petitions, 2(3), 46-72.

- Chua, J.H., Chrisman, J.J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39.

- Dini, M., Rovira, S., & Stumpo, J. (2014). A promise and a sigh: Innovation policies for SMEs in Latin America. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC.

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC] (2019). Social Panorama of Latin America 2019. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC] (2020). Afro-descendants and the matrix of social inequality in Latin America: challenges for inclusion. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC] (2020). Latin America and the Caribbean in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Economic and social effects. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC

- Dávalos, M., & Ramírez, O. (2019). Strategic planning as the basis for the success of family businesses in Paraguay. Latin Science Multidisciplinary Scientific Journal, 3(1), 166-185.

- Davis, J. (2006). Inside the DNA of the Family Business: A Conversation with Family Business Expert John A. Davis. Harvard Business Review, 84(8), 44-48.

- De la Garza-Ramos, M., Medina-Quintero, J., Mayer-Granados, E., & Jiménez-Almaguer, K. (2012). The family business: Development of its typologies from 1980 to 2009. CienciaUAT, 7(1), 28-33.

- Donckels, R., & Fröhlich, E. (1991). Are family businesses really different? European experiences from STRATOS. Family Business Review, 4(2), 149-160.

- Echaiz, M.D. (2010). The family protocol: Contracting in business families for the management of family businesses. Mexican Bulletin of Comparative Law, 43(127), 101-130.

- Fayol, H. (1916). Industrial and general administration. Principles of scientific management. Paris: Dunod Editeur.

- Ferraro, C., & Rojo, S. (2018). MSMEs in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Integrated Agenda to Promote Productivity and Formalization. Santiago de Chile: ILO.

- García, V., Meza, L., & Pedraza, F. (2018). Development of the dynamic capacity for the absorption of knowledge between family and non-family businesses in Bucaramanga, Colombia. Lebret Magazine, 10, 89-109.

- García-Olivares, A., & Beitia, A. (2019). Capitalist economic progress from the industrial revolution to its current crisis. Sociological Journal of Critical Thought, 13(1), 23-44.

- Gersick, K., Davis, J., McCollom, M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Gómez, M. (2019). The fourth industrial revolution: A great opportunity or a real challenge for full employment and decent work ? International and Comparative Journal of Labor Relations and Employment Law, 7(4), 276-315.

- Habbershon, T.G., & Williams, M.L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25.

- Hernández, P.H. (2011). Business management, a twentieth century approach, from scientific, functional, bureaucratic administrative theories and human relations. Scenarios, 9(1), 38-51.

- Herrera, D., Ramírez, G., & Rosas, J. (2017). Organizational Diversity and Complexity in Latin America. Analysis Perspectives. Mexico: Grupo Editorial Hess, S.A. de C.V.

- Leach, P. (1993). The family business. Buenos Aires: Granica Editions.

- López, D.M., Arias, L., & Rave, S. (2006). Organizations and administrative evolution. Scientia Et Technica, 12(31), 147-152.

- Lozano, P.M. (2009). Elements for consulting in family businesses. Thought and Management, 26, 214-237.

- Marchionni, M., Gasparini, L., & Edo, M. (2018). Gender gaps in Latin America. A state of affairs. Caracas: CAF.

- Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

- Mayo, E. (1945). Social problems of an industrial civilization. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Mera, P., & Bermeo, C. (2017). Importance of family businesses in the economy of a country. Publishing Magazine 4, 12(2), 506-531.

- Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2003). Challenge versus advantage in family business. Strategic Organization, 1(1), 127-134.

- Molina-Ycaza, D., & Sánchez-Riofrío, A. (2016). Obstacles for micro, small and medium enterprises in Latin America. Pymes, Innovation and Development Magazine, 4(2), 21-36.

- Molina, P.P., Botero, B.S., & Montoya, M.J. (2016). Family businesses: Concepts and models for their analysis. Thought and Management, 41, 116-149.

- Molina, P.P., Botero, B.S., & Montoya, R.A. (2017). Performance studies in family businesses: A new perspective. Management Studies, 33(142), 76-86.

- Munguía, L.R. (2015). Structure of a public policy for the family business in Honduras. Economics and Administration (E&A), 6(2), 144-153.

- Murillo, V.B., Almonte, L., & Carbajal, S.Y. (2020). Economic impact of the closure of non-essential activities due to Covid-19 in Mexico. An evaluation by the hypothetical extraction method. Accounting and Administration, 65(5) Special COVID-19, 1-18.

- Ordaz, B.G., Monroy, L.L., & López, R.M. (2010). Towards a public policy proposal for families in the Federal District. Mexico City: MC Editores.

- United Nations [UN] (2020). Report: The impact of COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean.

- International Labor Organization [ILO] (2020). MiPyme environment. Support measures for micro, small and medium enterprises in Latin America and the Caribbean in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. Lima: ILO, Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, 160.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD/CAF] (2019). Latin America and the Caribbean 2019. Policies for competitive SMEs in the Pacific Alliance and participating countries in South America, OECD publishing, Paris.

- Oxfam Mexico. (2021). The virus of inequality. How to rebuild a world devastated by the coronavirus through a fair, just and sustainable economy. Oxford: Oxfam GB.

- Perdomo, C.G., Vanoni, M.G., Quinchía, S.C., & Galindo, R.O. (2020). Family business: Strategy, capacity and performance. Medellín: Ceipa Editorial Fund.

- Ramírez, E., Baños, V., & Rodríguez, L. (2018). Family businesses in Mexico and Latin America: the challenge of institutionalization. In Economic growth, competitiveness and management of organizations: Looks and reflections, 169-195, edited by Ana Corla; Alejandro Rodríguez; Omar Rojas; Maria Gutierrez. Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Patria, S.A. de C.V.

- San Martín, R.J. & Durán, E.J. (2017). X-ray of the family business in Mexico. Puebla: UDLAP.

- Santamaría, F.E., & Chicaiza, C.V. (2016). Impact of the professionalization of family businesses on the generation of skills. Teuken Bidikay. Latin American Journal of Research in Organizations, Environment and Society 7 (9), 119-135.

- Sharma, P., Chrisman, J.J., & Chua, J.H. (1997). Strategic management of the family business: Past research and future challenges. Family Business Review, 10 (1), 1–35.

- Solís, P., Güémez, G.B., & Lorenzo, H.V. (2019). Inequality will speak for my race. Effects of ethnic-racial characteristics on inequality of opportunities in Mexico. Mexico City: Oxfam Mexico.

- Tagiuri, R., & Davis, J. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family business. Family Business Review, 9(2), 199–208.

- Tapies, J. (2011). Family business: A multidisciplinary approach. Universia Business Review, 32, 12-25.

- Taylor, F. (1911). Principles of scientific management. New York: Harper and Row.

- Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R. (2010). Family businesses, Latin American vision: Structure, management, growth and continuity. Mexico: Pearson.

- Trucco, D. (2014). Education and inequality in Latin America. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC. Social Political Series, 200.

- Vélez, M.D., Holguín, L.H., De la Hoz, P.G., Durán, B.Y., & Gutiérrez, A.I. (2008). Dynamics of the SME Family Business: Exploratory Study in Colombia. Colombia: You found.

- Viloria, N.J., & Luciani, T.L. (2015). Administrative thinking: A study of its problematic axes. Organizational Sapienza, 2(4), 119-143.

- Wahrlich, B. (1978). Evolution of administrative sciences in Latin America. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 44(1), 70–92.

- Ward, J., & Dolan, C. (1998). Defning and describing family business ownership configurations. Family Business Review, 11(4), 305-310.

- Yasunaga, M. (2020). Inequality and political instability in Latin America: Protests in Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia. IEEE Bulletin, 18, 366-382.