Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 5

Gap between Sophisticated Consumers and Sophisticated Behaviors: Analysis of the Portuguese in Social Sustainability

Isabel Oliveira, North Lusíada University

Jorge Figueiredo, North Lusíada University

Elizabeth Real de Oliveira, North Lusíada University

Citation Information: Oliveira, I., Figueiredo, J., & Oliveira, E.R. (2021). Gap between sophisticated consumers and sophisticated behaviors: Analysis of the portuguese in social sustainability. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 1-11.

Abstract

Social Responsibility is an issue that society in general is increasingly aware of. A fact that has led companies to adopt socially responsible measures in their strategic plan, as these will have an effect on their results. Thus, companies, in order to differentiate themselves from the competition, are more concerned with values, through Marketing associated with causes and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

However, there is still little evidence that this concern is reflected in the act of purchase, especially in countries with a low standard of living and different social realities. Given the existing gaps and the relevance of the topic, the aim of this study is to analyze whether Portuguese consumers know and attach importance to CSR and if this importance is translated into the act of purchase. To achieve this goal, 260 surveys were analyzed, distributed across 10 Portuguese districts, from February to April 2019. The statistical analysis of the data suggests that consumers are sophisticated in knowing and attaching importance to CSR. However, they do not show sophisticated behavior, as the price and quality of the product is the most important factor in the act of consumption. The gap between sophisticated consumer and sophisticated behavior is smaller among female consumers, with higher educational qualifications and higher monthly income.

Keywords

Corporate Social Responsibility, Sophisticated Consumer, Sophisticated Behavior.

Introduction

From the second half of the twentieth century, there is a greater awareness in society and concern for the economy, environment and social justice. It is in this context that companies focus their attention on implementing corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies. For Hay and Gray (1974), the rapid changes in society, coupled with business goals of growth and profit maximization, made social problems increasingly evident. This fact induces stakeholders to defend responsible social actions for companies. Consumers are one of the stakeholders that most influence companies by seeking to satisfy their interests in the pursuit of profit maximization (Lim et al., 2018). In addition, the behavior of socially responsible consumers is important for CSR success (Golob et al., 2019).

Studies with samples from different countries and time periods find that consumers are increasingly aware of social responsibility (SR) (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Costa et al., 2012). Several studies have found the positive relationship between socially responsible business actions and consumer reaction to their products/services (Bhattacharya & Sem, 2004; Becchettia et al., 2019; Bolton & Mattila, 2015; Gomes & Graca, 2019; Li et al., 2019). However, there is still no consensus in the literature indicating that consumers regard CSR as a deciding factor when buying (Barkakati et al., 2016; Castro-González et al., 2019; Garcia-Jiménez et al., 2017; Neequaye et al., 2019). In addition, although CSR has been widely analyzed in the literature, the social responsibility of private consumers has been less analyzed, as it is consumer behavior that influences companies (Schlaile et al., 2018).

Given the existing gaps and the relevance of the theme, the aim of this study is to analyze if the Portuguese consumer knows and gives importance to the concept of CSR and if this is a determining factor at the time of purchase. To check the robustness of the results, we analyze whether the results are consistent for the entire sample and for subgroups of the sample as a function of respondent characterization, such as gender, educational attainment, and monthly income. In the pursuit of this objective, a survey distributed across ten Portuguese districts is analyzed.

There are several factors that explain the relevance of this research. First, although there are studies analyzing consumer perceptions of CSR and its influence when buying in Portugal, research in this area is relatively recent. Second, most studies analyze the company's view and not the consumer's view. Third, the Portuguese consumer presents characteristics that differentiate him from the consumers analyzed in other studies. In Portugal, the standard of living is low and there are some social inequalities compared to existing studies. These characteristics may cause different behaviors in the factors to be met at the time of purchase. Fourth, the theme is not only current, but also crucial for companies that are increasingly concerned with customer satisfaction to identify opportunities and develop more assertive social responsibility (SR) strategies that benefit consumers, society, and consequently the companies themselves. Moreover, for Mohr and Webb (2005), the existence of CSR practices adds value to products.

The article is organized as follows. In this section, the theme, objectives, and relevance of research are introduced. Section two presents the literature review. Section three presents the methodology and the sample used. Section four presents and analyzes the empirical results. Final conclusions are presented in section five.

Literature Review

For Ayuso et al. (2013) there is no universal definition for CSR. Freeman & Hasnaoui (2011) argue that CSR encompasses many concepts and ideas, which vary according to the country of origin of the authors and organizations. It may be added that the existence of a complex and constantly evolving social environment causes a constant change in the notion of CSR.

The first author to define CSR was Bowen (1953) as the obligation of managers to adopt guidelines, make decisions and follow lines of action, which are compatible with the purposes and values of society. In contrast, Friedman (2020) argues for CSR economically. Enterprises operating within market rules and legal norms should seek to maximize profit to preserve their existence and ensure employment and income for workers, thereby contributing to the well-being of the population.

Carroll (1979) presents a broader view of the concept, encompassing four types of responsibilities, arranged in the form of a pyramid according to its importance: (1) economic, i.e., profit-making, which is the basis of (2) legal or law-abiding, (3) ethical, by adopting behaviors in accordance with moral codes and societal values, and (4) philanthropic, that is, the contribution to solving societal problems and improving the quality of life. Lai et al. (2010) define the concept as a set of voluntary activities undertaken by organizations to voluntarily increase economic, social and environmental performance. It is concluded that although there is no universal definition for CSR, transparent business behaviors based on ethical values, legal compliance and respect for people, society and the environment must be included (Singh & Verma, 2017).

Society has shown that it is increasingly aware of the importance of companies being socially responsible (Li et al., 2019). However, there is little empirical evidence that consumers have a favourable attitude towards these companies (Quazi et al., 2016). What consumers think about doing, and what they do, are two things that go completely off. The reasons given for this attitude are related to important factors at the time of purchase such as price, quality, brand, status, payment terms, promotions and after sales services (Acevedo et al., 2009; Barkakati et al., 2016; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Silva et al., 2018; Tolentino et al., 2019). The European Commission (2001) notes that consumers would be willing to pay more for products from socially responsible companies, but only a minority follow this principle. Carrigan and Atalla (2001) suggest the need to distinguish between sophisticated consumer and sophisticated buying behavior. The sophisticated consumer does not guarantee to adopt sophisticated behavior, hence the explanation for the gap between intention and attitude.

Socially responsible consumer behaviors are also influenced by factors such as: (1) social class and/or educational level, the higher these factors, the greater the influence of social factors (Coddington, 1990; Quintão & Giuliana 2015). (2) Collectivist values, people with collectivist characteristics tend to be more concerned with the environment and others than individualists (Belyaeva et al., 2018; Shelomentsev et al., 2018; Torelli et al., 2020). (3) Age and gender, women in the so-called middle age tend to attach greater importance to social factors relative to other women and men (Hasan, 2018; Trapero et al., 2011). (4) Corporate disclosure about CSR acts helps to create consumer awareness (Michal, 2018), as well as Catholic thinking (Michal, 2018). (5) The recognized brand in society reveals an important weight in the act of consumption, regardless of the practices of SR practiced (Cordeiro et al., 2018; Hossain et al., 2019 a; Hossain et al., 2020).

Pelsmacker et al. (2005) find that consumers would be willing to buy products from socially responsible companies if more information was available and if prices for these products were lower, as price is the main factor when buying. It should also be noted that consumers attach more importance to negative information about the attitude of the company towards society than to positive attitudes (Serpa & Fourneau, 2007).

Finally, it should be noted that socially responsible companies must disclose their practices to the market, as this will contribute positively to the consumer's attitude, creating value for the product or for the brand (Hossain et al., 2019 a & b). However, companies will have to bear in mind the form of disclosure performed as not all of them are well accepted by the market. Disclosure through techno marketing will positively affect the consumer's perceived attitude (Jahan et al., 2020) while others are not well accepted by the market (Khalil et al., 2020).

Methodology

The literature review concludes that although consumers are more aware of the importance of CSR, they are not able to translate this feeling into the act of purchase, hence the existence of a gap between the intention and the attitude of the consumer.

The aim of this study is to analyze the importance that Portuguese consumers attribute to CSR as a determining factor in consumption. To achieve this objective, the following research hypotheses are defined:

H1 Respondents know the concept of CSR and consider it important.

H2 What factors respondents/consumers meet at the time of purchase.

The analysis developed aims to test the hypotheses stated for the whole sample and to verify if the results are consistent with the different characteristics of respondents, according to gender, educational attainment, and monthly income.

The methodology used for sample collection is through a survey, structured based on the factors that should be considered as CSR practices and, in the empirical studies performed, namely (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004; Marques, 2012; Pomering & Dolnicar, 2009).

In the paper questionnaire, closed questions are used. These are easy to answer and require less time for the respondent and allow better and more efficient coding, analysis and interpretation of data. In some questions, respondents indicated the degree of importance in relation to the prepositions presented, using the Likert scale, which ranges from 1 to 5, with 1 meaning totally disagree and 5 strongly agree. On other issues, the scale ranges from 1 to 4, 1 means nothing related and 4 totally related. The questionnaire is divided into three parts, the characterization of the respondent, the degree of knowledge and the importance attributed to the concept of CSR and what factors to meet at the time of purchase.

The distribution of the survey across the ten districts of Portugal began in February 2019 and collection took place in April of that year. In the statistical treatment of the data and hypothesis tests, the EViews 9 is used. In the research, a 95% confidence interval is defined, that is, a margin of error of 5%, and statistical tests are performed, Student T, to evaluate the statistical significance of the variables analyzed at a level of statistical significance of 5%.

Table 1 presents the characterization of 260 respondents in the sample, of which 153 women (58.8%) and 107 men (41.2%).

| Table 1 Sample Characterization | |||||||

| Category | Scale | N | % | Category | Scale | N | % |

| Gender | Male | 107 | 41.2% | Literary Qualifications | Basic Education | 11 | 4.2% |

| Female | 153 | 58.8% | Secondary Education | 93 | 35.8% | ||

| Total Sample | 260 | University Education | 153 | 58.8% | |||

| Unanswered | 3 | 1.2% | |||||

| Marital Status | Single | 99 | 38.1% | Monthly Net Income | £ 1.000€ | 76 | 29.2% |

| Married/Union | 136 | 52.3% | [1.001€ - 2.000€] | 116 | 44.6% | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 16 | 6.1% | [2.001€ - 3.000€] | 48 | 18.5% | ||

| Widower | 1 | 0.4% | > 3.000€ | 12 | 4.6% | ||

| Unanswered | 8 | 3.1% | Unanswered | 8 | 3.1% | ||

| Number of Household Elements | 1 People | 42 | 16.2% | Age | < 18 years old | 8 | 3.1% |

| 2 People | 39 | 15.0% | [19 - 25 years old] | 51 | 19.6% | ||

| 3 People | 84 | 32.3% | [26 - 35 years old] | 70 | 26.9% | ||

| 4 People | 72 | 27.7% | [36 - 50 years old] | 92 | 35.4% | ||

| 5 People | 19 | 7.3% | > 50 years old | 37 | 14.2% | ||

| > 5 People | 1 | 0.4% | Unanswered | 2 | 0.8% | ||

| Unanswered | 3 | 1.1% | |||||

The age group with the largest number of respondents is between 26 and 35 years old, with 70 respondents (26.9%), followed by the 19 to 25 age group with 51 respondents (19.6%). The age group with the least respondents, with 8 (3.1%) is under 18 years old. Of the respondents, 136 (52.3%) are married or in union and 99 (38.1%) are single. Most respondents, 116 (44.6%), earn a monthly net income between €1,001 and €2,000 and the most frequent household consists of three or four members. It is also noted that more than half of the respondents, 153 (58.8%), have higher education and only 11 (4.2%) have basic education.

In the sample, women's educational level is higher than men. Respondents belong to ten districts, namely: Braga, Porto, Santarém, Aveiro, Portalegre, Bragança, Lisboa, Leiria, Évora and Viana do Castelo, with 134, 26, 23, 16, 14, 13, 11, 8, 8 and 7 respondents, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Table 2 presents the result of the survey on the Portuguese knowledge of the concept of CSR for the entire sample and disaggregated according to gender, age, educational and income. The objective is to analyze if the knowledge of the concept is identical for all respondents.

| Table 2 Knowledge of the Concept of CSR | ||||||||||||

| Do you know CSR practices? | N | Yes | No | N | Yes | No | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||||

| Total Sample | 258 | 215 | 83.3 | 43 | 16.6 | |||||||

| Gender | Literary Qualifications | |||||||||||

| - Male | 105 | 84 | 80 | 21 | 20 | - Basic Education | 10 | 6 | 60 | 4 | 40 | |

| - Female | 153 | 131 | 85.6 | 22 | 14.4 | - Secondary Educat. | 91 | 68 | 74.7 | 23 | 25.3 | |

| - University Educat. | 145 | 129 | 89 | 16 | 11 | |||||||

| Age | Monthly Net Income | |||||||||||

| - < 18 years old | 8 | 4 | 50 | 4 | 50 | - £ 1.000€ | 73 | 58 | 79.5 | 15 | 20.5 | |

| - [19 - 25 years] | 51 | 40 | 78.4 | 11 | 21.6 | - [1.001€ - 2.000€] | 112 | 93 | 83 | 19 | 17 | |

| - [26 - 35 years] | 66 | 58 | 87.9 | 8 | 12.1 | - [2.001€ - 3.000€] | 45 | 38 | 84.4 | 7 | 15.6 | |

| - [36 - 50 years] | 90 | 78 | 86.7 | 12 | 13.3 | - > 3.000€ | 11 | 11 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| - > 50 years old | 33 | 25 | 75.8 | 8 | 24.2 | |||||||

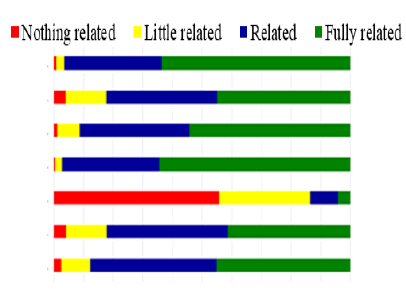

Table 3 presents the results of the descriptive analysis on the respondents' degree of agreement (from 1, to nothing related to 4, fully related) in the various dimensions of CRS.

According to Table 3, respondents know the various dimensions associated with CSR. The dimension with the highest average (3,538) is that companies worry about environmental issues, and the one with the lowest standard deviation, which reveals a greater consensus among respondents. The dimension with the lowest average (1,519) is for companies to have only profitability as their sole responsibility. It was concluded that respondents know the concept of CSR and its dimensions, showing greater importance to environmental responsibilities, but this should not be the sole responsibility of companies, and should act in accordance with moral and ethical values and legal and tax rules, contributing to the development of the society in which they operate, without forgetting their growth and profit.

| Table 3 CSR Dimensions | |||

| Dimension | N = 260 | ||

| Average | Stand. Deviation | % of Answers | |

| 1. Companies must: |  |

||

| 2. Worry about environmental matters. | 3,538 | 0.732 | |

| 3. Preserve their growth and contribute to economic development. | 3,158 | 0.956 | |

| 4. Act voluntarily in accordance with moral and ethical values. | 3,365 | 0.853 | |

| 5. Contribute to the development of society. | 3,515 | 0.803 | |

| 6. Have profilability as the sole responsibility. | 1,519 | 0.885 | |

| 7. Comply with legal and tax rules. | 3,035 | 1.063 | |

| 8. Meet the practices of RS without forgetting the profit. | 3,126 | 1.041 | |

In addition, respondents not only know the concept of CSR, but also attach importance to it. Among the various alternatives indicated in the survey, those with the highest average on a scale from 1 to 4 are: SR practices make respondents better (2,815), help express who they are (2,531) and reflect their personality (2,523). Of the various alternatives in the survey, the one with the lowest average (2,312) is the SR practices reflect the status image before others. This confirms the first research hypothesis.

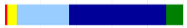

Table 4 presents the results of the descriptive analysis of the factors respondents meet at the time of purchase (from 1, strongly disagree to 5, strongly agree) to gauge the importance that respondents attach to CSR at the time of purchase.

| Table 4 Factors to be Met at Time of Purchase | |||

| Factors | N | Average | Standard deviation |

| Price | 260 | 4,031 | 1.149 |

| Price and quality | 260 | 4,438 | 1.025 |

| Product image | 260 | 3,596 | 1.133 |

| From companies with CSR | 260 | 3,465 | 1.174 |

| Third party suggestions | 260 | 3,381 | 1.171 |

Although respondents know and care about CSR, this is neither the only nor the first factor to attend to when buying. According to Table 4, the factor with the highest weight is the price and quality of the product (4,438) followed by the price (4,031) and product image (3,596). The products of companies that practice SR appear in penultimate place in the consumer hierarchy, thus it is one of the factors that have little weight in the act of choice when consuming and the factor that seems to present great controversy among the respondents. Conversely, the price and quality factor with the highest average is also the one with the lowest standard deviation, with greater consensus among respondents.

Table 5 presents the results of the descriptive analysis to gauge whether consumers are willing to pay a higher price to purchase products from SR firms (from 1, strongly disagree to 5, strongly agree), for the entire sample and for subgroups divided by gender, education and monthly net income characteristics of respondents.

| Table 5 The Consumer is Willing to Pay More for Products from Companies that Practice SR | |||||||

| Respondent Characterization | Factors | ||||||

| Question 1 Purchase products from companies with RS practices. |

Question 2 Willing to pay a higher price for products from companies with RS practices. |

Question 3 Willing to buy products from RS companies, even if there are cheaper products from companies without RS practices. |

|||||

| N | Averg. | S.D. | Averg. | S.D. | Averg. | S.D. | |

| Total Sample | 260 | 3,558 | 0,967 | 3,069 | 1,078 | 2,942 | 1,115 |

| % of answers |  |

|

|

||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 107 | 3,495 | 1,031 | 2,953 | 1,102 | 2,785 | 1,149 |

| Female | 153 | 3,601 | 0,920 | 3,150 | 1,056 | 3,052 | 1,083 |

| Literary Qualifications | |||||||

| Basic Education | 11 | 3,272 | 1,104 | 2,909 | 1,221 | 2,455 | 1,036 |

| Secondary Educat. | 93 | 3,430 | 0,852 | 2,957 | 0,988 | 2,925 | 1,055 |

| University Educat. | 153 | 3,647 | 1,023 | 3,150 | 1,123 | 2,987 | 1,164 |

| Monthly Net Income | |||||||

| £ 1.000€ | 76 | 3,513 | 0,959 | 3,093 | 1,038 | 2,947 | 1,031 |

| [1.001€ - 2.000€] | 116 | 3,543 | 0,888 | 3,094 | 1,063 | 2,931 | 1,125 |

| [2.001€ - 3.000€] | 48 | 3,542 | 1,148 | 2,938 | 1,227 | 2,771 | 1,292 |

| > 3.000€ | 12 | 3,917 | 1,083 | 3,500 | 0,798 | 3,583 | 0,793 |

The results of Table 5 corroborate the results of Table 4, that the price of the product is an important factor to attend to when buying. Respondents are unwilling to pay a higher price for products from companies with SR practices and show some indifference about buying these products when cheaper alternatives are available. From the values obtained in Tables 2 to 5, it can be stated that there is a mismatch between consumer thinking and behavior, corroborating the results of the Commission of the European Communities (2001) and Carrigan and Atalla (2001). The Portuguese are sophisticated consumers (Tables 2 and 3) in demonstrating knowledge and sensitivity on social responsibility issues. However, they do not exhibit sophisticated behaviors (Tables 4 and 5), as price and product quality are the most important factor at the time of purchase (Table 4). The purchase of products from companies that perform RS acts were relegated to second to last in the hierarchy. It is also noted (Table 5) that the Portuguese buy products from RS companies, as it is the three issues with the highest average and the highest consensus, but only if they do not have to pay a higher price. The other two questions, with lower averages, indicate that they do not buy or intend to buy products from SR companies if there are alternatives in the market at more affordable prices. It can thus be said that price prevails over SR.

However, it appears that this attitude is not the same for all respondents; it is women, those with higher educational attainment and those with higher monthly income who show a more sophisticated behavior. As both the level of education and the monthly income increase, there is an increase in averages, that is, there is a greater willingness to buy SR products regardless of the higher price.

Results agree with the previous analysis (Table 2), as these respondents are the best acquainted with the concept of CSR.

These results should be safeguarded, as it is not known whether these consumers behave more sophisticated due to their greater awareness of the importance of SR, or whether this behavior is due to higher monthly income. Higher education is also thought to imply higher monthly income, so the price factor is no longer crucial when buying when there is a better financial situation than those with lower income and/or lower educational.

Conclusions

Society is currently more aware of social responsibility issues. In this sense, the objective of this investigation is to assess the Portuguese knowledge about the concept of CSR. Additionally, it is intended to assess the importance that consumers attach to the concept at the time of purchase and whether this importance differs according to certain social characteristics.

The conclusions drawn from the survey of 260 respondents in ten of the eighteen districts of Portugal between February and April 2019 are:

(1) Most respondents know the concept of CSR as well as the different dimensions associated with it and are unanimous in the importance of this concept for society.

(2) Although respondents know and attach importance to CSR, this is not one of the most prominent factors at the time of purchase. Respondents attach more importance to factors such as price and quality when choosing which products to purchase. CSR is second to last in the hierarchy of factors to consider at the time of purchase.

(3) Regardless of factors to consider at the time of purchase, the Portuguese buy products from CSR companies.

(4) The Portuguese know the concept but are not prepared to pay a higher price for socially responsible products if alternatives to the market are available at lower prices.

(5) Higher-income female respondents are more likely to purchase higher-priced products from SR firms. It is also these respondents who know best and give greater importance to CSR.

It is concluded, in the sample under analysis, that consumers reveal to be sophisticated, know and attach importance to CSR, but do not exhibit sophisticated behavior, as there are other factors of greater importance at the time of purchase. Consequently, they are not willing to buy products from RS companies when in the market there are cheaper alternatives.

As a limitation of this study, we can point out the sample by questionnaire, which evaluates behavioral aspects, hence the information collected depends on the honesty of the interviewees. Respondents may not be true in their responses, indicating what should be desirable in society and not reality. To overcome this limitation, respondents were asked to provide more genuine information about their perceptions, highlighting the importance of this attitude for the reliability of the research.

The results found raise additional questions for future research. The analysis is cross-sectional, referring to the attitude of respondents in the year 2018. One of the future surveys is to perform a temporal analysis, in different time periods, to gauge the evolution of consumer thinking/behavior towards CSR.

References

Acevedo, C.R., Primolan, L.V., Nohara, J.J., & Zilber, S.N. (2009). Consumer representations on corporate social responsibility and the relationship with the purchase decision. Unimep Administration Magazine, 7(2), 76-95.

Ayuso, S., Roca, M., & Colomé, R. (2013). SMEs as “transmitters” of CSR requirements in the supply chain. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal.

Barkakati, U., Patra, R.K., & Das, P. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and its impact on consumer behaviour-a consumer's perspective. International Journal of Sustainable Society, 8(4), 278-301.

Becchetti, L., Corrado, G., Pelligra, V., & Rossetti, F. (2019). Satisfaction and preferences in a legality social dilemma: Comparing the Direct and Indirect Approach.

Belyaeva, Z., Scagnelli, S., Thomas, M., & Cisi, M. (2018). Student perceptions of university social responsibility: implications from an empirical study in France, Italy and Russia. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 14(1/2), 23-42.

Bhattacharya, C.B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9-24.

Bolton, L.E., & Mattila, A.S. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility affect consumer response to service failure in buyer–seller relationships?. Journal of Retailing, 91(1), 140-153.

Bowen, H. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. Harper & Row, New York.

Brown, T.J., & Dacin, P.A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68-84.

Carroll, A.B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497-505.

Castro-González, S., Bande, B., Fernández-Ferrín, P., & Kimura, T. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and consumer advocacy behaviors: The importance of emotions and moral virtues. Journal of Cleaner Production, 231, 846-855.

Coddington, W. (1990). It’s no fad: Environmentalism is now a fact of corporate life. Marketing News, 15(7), 7.

Commission of the European Communities (2001). Green paper: Promoting a European framework for corporate social responsibility, Brussels.

Cordeiro, R.A., Brandão, M.H., & Strehlau, V.I. (2018). Exploitation of Labor in Product Manufacturing: Who Cares?. Revista Interdisciplinar de Marketing, 8(1), 39-50.

Freeman, I., & Hasnaoui, A. (2011). The meaning of corporate social responsibility: The vision of four nations. Journal of business Ethics, 100(3), 419-443..

Friedman, M. (2020). Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago press.

Garcia-Jiménez, J.V., Ruiz-de-Maya, S., & Lopez-López, I. (2017). The impact of congruence between the CSR activity and the company's core business on consumer response to CSR. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 21, 26-38.

Golob, U., Podnar, K., Koklic, M.K., & Zabkar, V. (2019). The importance of corporate social responsibility for responsible consumption: Exploring moral motivations of consumers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 416-423.

Gomes, S., & Graça, P. (2019). Consumer perception of corporate social responsibility: Points of view from Portuguese undergraduate students. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 15(1-2), 76-92.

Hasan, M.N. (2018). Sustainable and socially responsible business: doable reality or just a luxury? An exploratory study of the Bangladeshi manufacturing SMEs. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 14(4), 473-506.

Hay, R., & Gray, E. (1974). A Blow-by-Blow History of Business Social Responsibility. Management Review, 63(7), 51-53.

Hossain, M., Anthony, J., Beg, M., & Zayed, N. (2019 a). The consequence of corporate social responsibility on brand equity: A distinctive empirical substantiation. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18(5), 1-8.

Hossain, M., Anthony, J., Beg, M., Hasan, K., & Zayed, N. (2020). Affirmative Strategic Association of Brand Image, Brand Loyalty, and Brand Equity: A Conclusive Perceptual Confirmation of the Top Management. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 19(2), 1-7.

Hossain, M., Hasan, R., Kabir, S., Mahbub, N., & Zayed, N. (2019 b). Customer Participation, Value, Satisfaction, Trust and Loyalty: An Interactive and Collaborative Strategic Action. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18(3), 1-7.

Jahan, I., Bhuiyan, K., Rahman, S., Bipasha, M., & Zayed, N. (2020). Factors influencing consumers’ attitude toward techno-marketing: an empirical analysis on restaurant businesses in Bangladesh. International Journal of Management, 11(8), 114-129.

Khalil, M., Rasel, M., Kobra, M., Noor, F., & Zayed, N. (2020). Customers attitude toward SMS advertising: a strategic analysis on mobile phone operators in Bangladesh. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 19(2), 1-7.

Lai, C., Chiu, C., Yang, C., & Pai, D. (2010). The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 457-469.

Li, Y., Liu, B., & Huan, T. (2019). Renewal or not? Consumer response to a renewed corporate social responsibility strategy: Evidence from the coffee shop industry. Tourism Management, 27, 170-179.

Lim, R., Sung, Y., & Lee, W. (2018). Connecting with global consumers through corporate social responsibility initiatives: A cross-cultural investigation of congruence effects of attribution and communication styles. Journal of Business Research, 88, 11-19.

Marques, P. (2012). Social Responsibility of Companies and Consumers: The necessary articulation. Higher Institute of Economics and Management, Master in Marketing, Lisbon, Portugal.

Michal, M. (2018). Consumer social responsibility. Annales Etyka w Zyciu Gospodarczym, 21(7), 97-109.

Mohr, L., & Webb, D. (2005). The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 121-147.

Neequaye, E.K., Amoako, G.K., & Attatsitsey, M. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and purchase intentions: perceptions and expectations of young consumers' in Ghana. International Journal of Sustainable Society, 11(1), 44-64.

Pelsmacker, P., Janssens, W., & Mielants, C. (2005). Consumer values and fair-trade beliefs, attitudes and buying behaviour. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 2(2), 50-69.

Pomering, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2009). Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR Implementation: Are Consumers Aware of CRS Initiatives?. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 285-231.

Quazi, A., Amran, A., & Nejati, M. (2016). Conceptualizing and measuring consumer social responsibility: a neglected aspect of consumer research. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(1), 48-56.

Quintão, R., & Giuliana, I. (2015). A influência da adoção de práticas de responsabilidade social corporativa no comportamento de compra da alta e baixa renda. Revista Economia & Gestão, 15(41), 231-255.

Schlaile, M., Klein, K., & Böck, W. (2018). From Bounded morality to consumer social responsibility: A transdisciplinary approach to socially responsible consumption and its obstacles. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(3), 561-588.

Serpa, D., & Fourneau, L. (2007). Corporate social responsibility: An inquiry into consumer perception. RAC - Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 11(3), 83-103.

Shelomentsev, A., Kozlova, O., Antropov, V., & Terentyeva, T. (2018). Buildup of federal universities social responsibility in the context of development of Russia's regions. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 14(1/2), 187-204.

Silva, M.E., Aguiar, E.C., Falcão, M.C., & Costa, A.C.V. (2012). A perspectiva responsável do Marketing e o Consumo Consciente: Uma interação necessária entre a empresa e o consumidor. Revista Organizações em Contexto, 8(16), 61-90.

Silva, R., Seibert, R., Callegaro, A., & Neto, E. (2018). A responsabilidade social e sua influência no consumo consciente. Revista de Administração de Roraima, 8(1), 104-126.

Singh, A., & Verma, P. (2017). How CSR Affects Brand Equity of Indian Firms?. Global Business Review, 18(3), Suppl., S52-S69.

Tolentino, R., Filho, C., & Falce, J. (2019). Does the ethical behavior of corporations affect relationships with their brands? influence of consumer ethical perception (PEC) on consumer loyalty. Theory and Practice in Administration, 9(2), 121-136.

Torelli, C., Leslie, L., To, C., & Kim, S. (2020). Power and status across cultures. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 12-17.

Trapero, F., Lozada, V., & García, J. (2011). The consumer before corporate social responsibility: Attitudes according to age and gender. Administration Notebooks, 24 (43), 285-305.