Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

Geographical Indication for Gastronomy Tourism: Maximising Intellectual Property Value and Branding

Albattat Ahmad Rasmi, Management & Science University

Jeong Chun Phuoc, Management & Science University

Zulhabri Othman, Management & Science University

Norhidayah Azman, Management & Science University

Citation Information: Rasmi, A.A., Phuoc, J.C., Othman, Z., & Azman, N. (2022). Geographical indication for gastronomy tourism: Maximising intellectual property value and branding. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(2), 1-13.

Abstract

Mega-trends influenced by development and cutting-edge marketing technologies have emerged in the tourist business of the twenty-first century. Gastronomy tourism is one among them. This research aims to identify characteristics that influence the growth of astronomy tourism in order to predict supply determinants for worldwide marketing operations. A valid foundation for separating commodities of food goods may be found by focusing on the geographical origins of a culinary cuisine. As a result, the growing dependence and usage of "geographical indicators" (GIs) might include distinctive traits linked with a certain area or distinguishing qualities based on the history, culture, and folklore of a specific geographical region. The commercial value and influence of GI indicators on gastronomic tourism, as well as the usage of GI as a new branding strategy, are discussed in this study.

Keywords

Geographical Indication, Gastronomy Tourism, Intellectual Property, Marketing, Branding, Strategy./p>

Introduction

Most items used and promoted in gastronomic tourism, as well as the tourist business in general, are protected by Intellectual Property Rights in today's globe (IPRs). Intellectual property, as a whole, delivers significant benefits and advantages to all gastronomic tourism players (Seyitoğlu & Ivanov, 2020). From upgraded versions of mobile phones to more fuel-efficient autos, it honors inventors and innovators for converting ideas into practical goods that have revolutionized and enhanced the world of tourism in Asia-Pacific (Liu & Jiang, 2020; Vandecandelaere et al., 2020). Intellectual property is now widely acknowledged as a primary driver of innovation (Dutta et al., 2020). Without a doubt, intellectual property benefits lives, promotes economies, and safeguards the environment in the culinary tourism industry by guaranteeing that new, high-quality ideas are generated throughout society on a regular basis (Dewalska-Opitek & Hofman-Kohlmeyer, 2021). Everyone from a scientist in a lab to a maker in his garage thinking up the next great innovation uses IP to progress their job. Gastronomy in the field of tourism is no exception (Yongxun & Lulu, 2021; Rejeb et al., 2021; Sottile et al., 2020)

Since the World Tourism Organization (WTO) recognized tourism as a vital contributor to commerce and development (Nurani et al., 2021), the tourist industry has had constant expansion in the service sector. It claims that tourism has become an important part of global business and a substantial source of income for both rich and poor nations (Yongxun & Lulu, 2021; Rejeb et al., 2021; Sottile et al., 2020). The IP system's components have a wide range of applications in the tourism industry, particularly in culinary tourism. Building and utilizing brands is crucial for the service sector, and hence for the tourism industry, in general (Nurani et al., 2021). For building and monetizing a brand for gastronomic tourism, trademarks, geographical indications, certified marks, collective markings, and industrial designs, as well as other intellectual property rights (IPRs) such as patents, copyrights, and trade secrets, are essential (Ghouri et al., 2021). Gastronomy tourism benefits greatly from all intellectual property legal rights that offer an exclusive right of use and the ability to prevent unauthorized third parties from benefiting from that right (Yongxun & Lulu, 2021; Rejeb et al., 2021; Sottile et al., 2020).

Geographical Indications (GIs)

In the world of marketing, geographical indicators are a relatively new notion intellectual property is a term used to describe the Geographical indications (GIs) are defined as indications that identify a good as originating in the territory of a member, or a region or locality within that territory, where a given quality, reputation, or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographic origin, according to the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIP) (Fernández-Zarza et al., 2021; Ranjan, 2021; Defossez, 2017).

International commerce made it critical to attempt to integrate the many techniques and criteria that countries used to register GIs (Supriatna et al., 2021). The Paris Convention on trademarks (1883, still in effect with 176 signatories) was the first effort, followed by a considerably more detailed provision in the 1958 Lisbon Agreement on the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their Registration (Friedmann, 2020; de Almeida & Carls, 2021). Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Congo, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czech Republic, North Korea, France, Gabon, Georgia, Haiti, Hungary, Iran, Israel, Italy, Macedonia, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Nicaragua, Peru, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Togo, and Tunisia are among the 28 countries that have signed the Lisbon Treaty (Delimatsis, 2021). Members of the Lisbon Agreement have registered over 9000 geographical indicators (Silva & Paul, 2021). When the WTO TRIPS talks were completed in 1994, all 164 WTO member nations (as of August 2016) agreed to define some fundamental rules for the protection of GIs in all member countries. In TRIPS, WTO member countries are subject to two essential duties in relation to GIs.

Article 22 of the TRIPS Agreement says that all governments must provide legal opportunities in their own laws for the owner of a GI registered in that country to prevent the use of marks that mislead the public as to the geographical origin of the good. This includes prevention of use of a geographical name which although literally true “falsely represents” that the product comes from somewhere else. Article 22 of TRIPS also says that governments may refuse to register a trademark or may invalidate an existing trademark (if their legislation permits or at the request of another government) if it misleads the public as to the true origin of a good (Richards, 2020). According to Article 23 of the TRIPS Agreement, all governments must provide GI owners the legal right to ban the use of a geographical indicator to identify wines that are not from the location specified by the geographical indication. Even if the public is not being misled, there is no unfair competition, and the genuine origin of the product is revealed or the geographical designation is complemented by phrases like "kind, “stype "limitation” or the like, this applies. Geographical indicators that indicate spirits must be given the same level of protection (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020). Governments may refuse to register or cancel a trademark that competes with a wine or spirits GI, regardless of whether the trademark misleads or not, according to Article 23 (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020).

Furthermore, TRIPS Article 24 allows a number of exceptions to the protection of geographical indications, which are especially significant for wines and spirits geographical indications (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020). Members, for example, are not required to safeguard a geographical indication if it has become a generic phrase for characterising the product in issue. Measures to execute these rules should not jeopardise already obtained trademark rights; and, in some cases — such as long-established usage — continuing use of a geographical indicator for wines or spirits may be permitted on the same scale and nature as before (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020). WTO member nations are debating the formation of a “multilateral registry” of geographical indications as part of the Doha Development Round, which began in December 2001(Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020). Some nations, such as the EU, are advocating for a legally binding register, while others, such as the US, are arguing for a non-binding system in which the WTO is merely advised of the members' respective geographical indications (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020).

Some states involved in the talks (Particularly the European Communities) want to go even farther and discuss the inclusion of Geographical Indications (GIs) on items other than wines and spirits under TRIPS Article 23 (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020). These states contend that expanding Article 23 would improve the international protection of these trademarks. Other nations, particularly the United States, reject this plan, questioning the necessity to extend the enhanced protection of Article 23 to other goods. They are worried that, in most situations, Article 23 protection is insufficient to offer the consumer advantage that is the primary goal of GIs legislation. Malaysia was also worried about gourmet tourism (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020).

GI Practices in United States, Southeast Asian and European Union

In the United States, GIs are typically considered as brands and trademarks, with GI protections administered by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), as well as labelling rules for wine, malt drinks, beer, and distilled spirits by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020). ASEAN follows suit, implementing the TRIPS Agreement in a manner similar to that of the United States (Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018); however, some nations, such as the Philippines, Brunei, and Myanmar, expand GI protection under trade mark or certification legislation to include gastronomy touris (Rahmah, 2018). TRIPS do not compel countries to create a separate system of protection for GIs, while the vast majority of WTO members have done so or are preparing to do so (Motari et al., 2021; Richards, 2020). There was no need to design a separate system specialized to GIs since the US had been safeguarding them for decades before TRIPS (Schipper et al., 2018). Furthermore, the trademark system was well-known among practitioners, stakeholders, and judges. As a result, the United States elected to continue to protect GIs as trademarks under the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) register and US common law, as explained below (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020).

GIs as certification and collective marks denoting regional origin are protected under Section 4 of the Trademark Act of 1946 (as modified) (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). GIs may also be protected as trademarks with an appropriate proof of acquired uniqueness via usage, even though the great majority of GIs are protected under Section 4 (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). Collective trademarks are primarily used to ensure a product's features, such as its geographical origin, and they are held by a public or private organisation, such as a trade association, which enables its members to use them commercially (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). While certification marks are used to show that a product has been created in accordance with certain requirements, such as a geographical location of production, they are the property of a company that does not sell the product but verifies that it complies with those standards. GIs are primarily regarded as brands and trademarks in the United States and ASEAN, but the European Union protects GIs via a variety of defined quality systems (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018).

In the European Union, GIs are used to preserve product names and promote their distinctive features, which are intimately tied to their geographical origin as well as traditional know-how for culinary tourist activities (Zappalaglio, 2021). The names of items for which an inherent relationship exists between product qualities or features and geographical origin are protected under EU quality schemes Open as an external link. There are a few:

1. PDOs (protected designations of origin) for agricultural and culinary items, as well as wines.

2. PGIs (protected geographical indications) for agricultural and culinary goods, as well as wines.

3. Geographical indications (GI) for alcoholic beverages and scented wines

The acknowledgment of GIs allows customers to trust and differentiate such items, while also assisting manufacturers in effectively marketing their products inside the. The geographical indicators system in the European Union protects the names of items that come from certain places, have distinctive attributes, or have a reputation tied to the manufacturing territory. This is commonly used throughout the EU for gourmet tourism (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018; Zappalaglio, 2021).

Differences in implementation of GI among United States, South East Asian and European Union

A difference in mindset about what defines a “genuine” product is one of the causes of confrontations between the United States, ASEAN, and the European Union (Zappalaglio, 2021). The predominant notion in Europe is that of terroir: that a geographical place has a distinctive quality that necessitates the careful use of geographical labels. Thus, anybody with the correct breeds of sheep may create Roquefort cheese if they live in the right section of France, but no one outside of that part of France can manufacture a blue sheep's milk cheese and call it Roquefort, even if they exactly replicate the technique outlined in the Roquefort definition.

In the United States and Southeast Asia, on the other hand, name is often regarded as an issue of intellectual property (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). Meadowcreek Farms owns the name Grayson, and they have the right to use it as a trademark (Süess, 2012). Nobody, not even in Grayson County, Virginia, may call their cheese Grayson, yet Meadowcreek Farms might use that name if they acquired another farm elsewhere in the United States, even if it wasn't in Grayson County (Süess, 2012). It is thought that their desire to protect their company's reputation is a quality guarantee. The majority of the tension between the United States and Europe in their views regarding geographical names stems from this disparity (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). However, there is considerable overlap, especially when it comes to American goods taking a European perspective on the subject (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). Vidalia onions, Florida oranges, and Idaho potatoes are among the most well-known of these crops (Lucier & Parr, 2020). In each of these situations, the state governments of Georgia, Florida, and Idaho filed trademarks, allowing their growers—or, in the case of the Vidalia onion, only those in a specific, well-defined geographic region inside the state—to use the name but prohibiting others from doing so (Lucier & Parr, 2020).

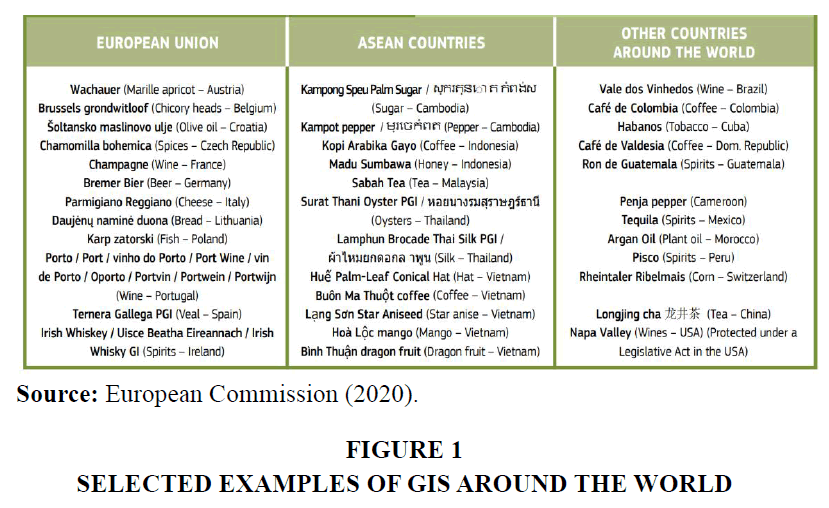

Vintners in the different American Viticultural Areas are seeking to build well-developed and distinct identities as New World wine obtains popularity in the wine industry, and the European notion is gradually finding favour in American viticulture (Rosas, 2020; Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018). Finally, the United States has a long history of imposing extremely tight restrictions on its native kinds of whiskey; most significant are the rules for calling a product whiskey (which requires the whiskey to be manufactured in the United States according to specified standards) and the need, enforced by federal law and many international agreements (including NAFTA), that a product branded Tennessee whiskey be a straight Bourbon (Pacult, 2021) (Figure 1).

Gastronomy Tourism

Experiencing destination-specific meals and drinks, finding new foods and beverages, tasting exceptional foods and beverages, seeing the making of different dishes, eating straight from the hands of a famous chef, visiting a particular restaurant and wine cellar, or at the absolute least acting in this way during the segment of the trip (Çetin, 2021; Visković & Komac, 2021; Celebi et al., 2020). Cultural and historic qualities are being prioritised in tourism projects. As a consequence, tourist preferences have changed toward destinations with significant cultural characteristics. This tourism initiative has emphasised the subject of preserving indigenous tourist values (Yalin, 2021). As a consequence of the negative effects of mass tourism on the natural environment, tourism practises that respect nature and cultural values while emphasising conservation have increased in favour. In this context, gastronomy tourism, agrotourism, and rural tourism efforts have gained traction (Çetin, 2021; Visković & Komac, 2021; Celebi et al., 2020). On-site food and beverage outlets are viewed as an important part of the tourist experience, accounting for one-third of visitor spending. A tourism law has been prepared in this context to minimise misunderstandings between indigenous values that are gaining popularity both in the country and throughout the world (Çetin, 2021; Visković & Komac, 2021; Celebi et al., 2020).

Protection of Geographical Indications in Gastronomy Tourism

The rules have been altered. Competition is fierce, and those who see the intangible asset's potential for differentiating and adding value to physical things are rewarded in the knowledge-based economy (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020). Intangible assets are safeguarded, preserved, monetized, and enforced via the intellectual property system, which provides a framework and methods for doing so (Török et al., 2020). The millennial tourism trend is to go to places where regional cuisines are made (Pavlidis & Markantonatou, 2020). The rise of gourmet tourism was influenced by tourist preferences for regional cuisine. Local food, on the other hand, is inadequate to support this kind of tourism's expansion. Local items, in addition to the food culture of the area, attract tourists, assist to brand the destination, and contribute to its economic prosperity (Ianioglo & Rissanen, 2020). The indigenous people's way of life, the destination's history, and its customs and traditions, on the other hand, all play a part in the growth of gourmet tourism (Richards, 2021).

From a geographical aspect, gastronomy tourism is an important co-creator of landscape. It adapts global elements to local contexts, replete with their inherent benefits and drawbacks, and reimagines place via cultural innovations. As a result, the traditional landscape is transformed into a culinary landscape that reflects the intricacies of modern living as well as the geographic and cultural diversity that different cultural traditions create (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020). In an increasingly globalised world, gourmet tourism allows regions to leverage their cultural distinctiveness and diversity as a competitive advantage. Gastronomy tourism is growing as a result of globalisation and mobility (Derek, 2021). As a result, cuisine has become a major factor in holiday destination selection, as well as a driving force behind experience tourism, such as wine tourism (Pavlidis & Markantonatou, 2020). Destinations must identify and sell the features that contribute to their image, such as distinctive commodities produced from their cultural and natural resources, in order to achieve this (Török et al., 2020). While food is organically distributed, both physically and somewhat ethereally, it has an impact on and shapes location, mostly via changes in social and economic systems, as well as land use. The historical mechanisms through which legacy operates as a resource for territorial development are difficult to properly and totally explain due to the complexity of legacy (Pavlidis & Markantonatou, 2020).

This is especially true since the territory is a complicated construct in which many stakeholders (residents, visitors, and investors) interact based on their own perspectives, motivations, knowledge, experiences, and expectations (Török et al., 2020). Numerous studies on gastronomy tourism show that the economic advantages of cuisine may be divisive in host cities (Török et al., 2020; Ketter, 2020). While Birch & Memery (2020), sees local food as a vehicle for cultural tourism experiences and the sale of local food products as a way to strengthen local identity, Visković & Komac (2021) remind us that gastronomy tourism does not always contribute to cultural, social, economic, or territorial development, at least not to the extent that is expected. This is especially true in today's more competitive global culture (Török et al., 2020; Ketter, 2020; Visković & Komac, 2021). Given the fact that many urban residents grew up in rural areas, it's critical to address the intricacies of urban-rural relations, which includes a return to local landscapes and terroir (Visković & Komac, 2021).

By involving local food system actors (farmers, producers, and processors, chefs and caterers, festival organisers and managers, policymakers and authorities), as well as the community, gastronomy tourism reduces the spatial and technological distances created by industrialization and globalisation of agricultural food supply chains (Payandeh et al., 2020). Through product manufacture, processing, and transformation, they learn indigenous skills, historical and cultural practises, and traditional knowledge (Duxbury et al., 2021). Since a consequence, regional differences emerge, as food has become an important element. This expansion is characteristic of cities, but it is often less obvious in rural areas, where it has an influence on spatial development and regional identity, for example, via the creation of a tourist gastronomic region and a tourism scape (Lee et al., 2020).

Geographical Indication as New Marketing Strategy in Tourism Industry

Consumers of regional products value labels that incorporate regional certification, according to Čehić et al. (2020) they came to the conclusion that GI labels boost buyers' willingness to pay more for regionally protected items. According to Jarma Arroyo et al. (2020), provenance information has a significant positive impact on the acceptability of virgin olive oil. Katt & Meixner (2020) look at German consumers' preferences for regional foods as well as their willingness to pay a premium for them (WTP). The preceding literature analysis exemplifies the western school of thought on GI products and how they are viewed. GI protection clearly plays a vital part in marketing, as seen by their contributions. In order to determine the characteristics of GI in a marketing setting, the following components are highlighted:

Brand Geographical

In the business cycle, branding and brand establishment take a long time. Geographic markers have a lengthy history and a loyal following of customers, but the study shows that these are historically established brands in the Western world, indicating that buyers are more familiar with these things and that there is a favourable attitude toward regional markers (Duxbury et al., 2021; Čehić et al., 2020; Török et al., 2020; Ketter, 2020; Visković & Komac, 2021). Individual loyalty to geographical markers changes, according to Teuber. As a consequence of belonging, a positive mindset prevails in the market.

Product Differentiation

In the marketing of a product, differentiation is crucial. The system of qualities used to differentiate the product is also included in the case of geographical indications. GI marketing is becoming more prominent and supportive as a result of product differentiation and legal protection. Exclusive rights, as previously said, provide producers a one-of-a-kind opportunity to build a distinctive marketing strategy. Geographical indicators are becoming more widely recognized as useful tools for product differentiation, and they may help enhance economic efficiency by motivating producers to provide the proper supply to the market (Duxbury et al., 2021; Čehić et al., 2020; Török et al., 2020; Ketter, 2020; Visković & Komac, 2021).

Adding Value to Marketing

Good marketing and promotional actions to influence consumer perceptions of the product's quality and value are critical to commercialising a GI. Establishing a favourable reputation for a GI product, on the other hand, is not easy. To create a meaningful GI, you'll need a lot of time, patience, money, quality control, and a well-thought-out marketing strategy, to name a few things. For example, it is claimed that “Champagne” took up to 150 years to develop its premium brand image (Duxbury et al., 2021; Čehić et al., 2020; Török et al., 2020; Ketter, 2020; Visković & Komac, 2021).

Specialization in Marketing

GIs assist to honour and encourage cultural contributions and reward the ingenuity of cultural and traditional knowledge by creating specialised markets for indigenous peoples' well-known commodities and prohibiting others from capitalising on that reputation (Duxbury et al., 2021; Čehić et al., 2020; Török et al., 2020; Ketter, 2020; Visković & Komac, 2021).

GI for Indigenous Gastronomy Tourism

The majority of GI-protected foods are land-based, implying significant historical and symbolic ties between location and product (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020). Because GIs are a sort of collective monopoly right, niche marketing and food product differentiation may be achievable with this awareness of where these food items are located at the junction of culture and geography. This has the twin benefit of enabling food product manufacturers in the nation of the indication to distinguish their goods in the market while also acting as a barrier to entrance into their market sector (Ahmad et al., 2021; Sayuti et al., 2020). To be explicit, the standards contained in the GI registration determine how, where, and with what ingredients the food product will be manufactured. GIs give an opportunity to capture the ‘rent' implicit in the appellation for the class of producers (and their goods) who qualify for protection (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020).

However, safeguarding GIs has unintended consequences since them work to publicize the locations and areas that they utilize for their names: Burgundy provides its name to one of the world's best-known wines, but the region of Burgundy becomes renowned because of its wine (Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021). Dutfield & Suthersanen (2019) , point out the general conflicts between contemporary intellectual property right systems and customary law and traditional cultural property rights, while acknowledging the positive aspects of GIs for the protection of indigenous peoples' knowledge toward the producer of the traditional cuisine and the origin of the cuisine. Even though indigenous communities may hold concepts similar to 'property rights,' the communities' 'informal innovation system' and cultural exchange systems raise deeper conflicts between contemporary IPRs' norms, practices, and economics and indigenous communities' cultural rights and customary practices (Kuruk, 2020). GIs as an intellectual property protection tool have unique characteristics that, in comparison to other IPRs, make them more suitable to indigenous populations' traditional practices:

Information is kept in the Public Domain

The knowledge/information encoded in the protected indication (or the product) stays in the public domain since no organization (company or person) has exclusive monopolistic control over it. As a result, concerns about the monetization of traditional knowledge as a result of GIs are overstated. The codification of well-established practices into regulations that become public knowledge (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020; Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021; Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2019) is a kind of protection. However, since the information incorporated in the item is not protected, there are concerns about traditional knowledge being misappropriated. Nonetheless, the codified standards do not reveal all of the local (indigenous) knowledge related with the product and its manufacturing process.

Rights are (Possibly) Indefinite

The specific indication is protected as long as the good-place-quality relationship is preserved and the indication is not made generic. Many indigenous cultures see their knowledge as a cultural treasure that must be preserved for the sake of their culture's survival. It's also helpful to remember that the rules of practice linked with a GI might vary and alter over time when recognizing this factor of compatibility. Without a doubt, this raises basic problems about the underlying characteristics of a "traditional" practice/food product, as well as the degree to which modification is acceptable (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020; Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021; Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2019)

The Protection's Scope is Compatible with Cultural and Traditional Rights

To begin with, GIs are a collective right that is "owned" by all producers across the supply chain that follow the defined regulations and produce inside the delineated geographical territory (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020; Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021; Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2019). The 'owners' of a GI do not have the right to transfer the indication, which is granted to trademark and patent holders (Article 21, 22, 23 and 24, TRIPs Agreement) Following this, the product-quality-place relationship that underpins GI-protection automatically prevents the indication from being transferred to manufacturers beyond the designated territory. The indicator cannot be used on 'similar' items that come from beyond the defined geographical area or are made differently if they come from within the territory. Protecting an indicator has the effect of limiting the class and/or location of persons who can use it (Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020; Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021; Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2019).

GI as Competitive Edge for Branding

Unfortunately, depending on GI-based strategies to build and maintain competitive market advantages have downsides (Punchihewa, 2020). To begin, geographical identifiers are owned by a set of enterprises operating in a certain geographic area, rather than by a single manufacturer. As a consequence, each manufacturer must provide their corporate/brand name and a location. To put it another way, GIs are more likely to generate primary demand for an entire product category than secondary demand for a single brand operating inside that product class (Styvén et al., 2020). Businesses have an incentive to define their geographic domain more accurately in order to improve their ability to differentiate their products. Local meals and commodities, it may be said, play an important part in visitor activity. In order to transmit these commodities on to future generations, geographic indicators must be recorded on them. Geographical designations help to preserve the region's culture, traditions, and customs, as well as its tourist assets and cultural history, and they help to ensure its long-term viability (Panda et al., 2020).

This situation displays how things with regional designations assist to tourist development. When a geographical indicator is related to culinary tourism, it produces a lot of money for the region by sending tourists to sites where goods are made. It also acts as a draw by emphasizing the region's tourism attractions, and it may aid in growth (Marescotti et al., 2020). Taking all of these considerations into account, it is feasible to infer that regionally produced goods and culinary tourism are closely related. The geographical markers play an important role in the development of the region's culinary character. They also protect traditional production and the essence of the place, which is handed down from generation to generation (Özdemir, 2018). The developers of a GI identity are unable to keep all of the benefits associated with the GI identity (which they assisted in creating). More participants will enter the geographical area after a GI "brand" becomes successful in order to profit from the GI's brand equity (Fusté-Forné, 2020). For example, the Idaho potato brand may be used by any producer who produces potatoes in Idaho; it is not limited to a single producer or a group of farmers who originated and marketed it (Lu et al., 2021). This might lead to a rise in GI sector production, cutting product scarcity and, as a consequence, premiums.

As a consequence, GIs do not always protect against competition, since other businesses may enter the “market” as long as they meet the GI collective's rules (Punchihewa, 2020; Styvén et al., 2020; Panda et al., 2020; Marescotti et al., 2020; Fusté-Forné, 2020; Başaran, 2021 and Jaelani et al., 2020; Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021; Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2019). It's possible that there's a tendency to expand the geographical area where the identification was issued. Technically, drawing a line and claiming a geographical advantage in making a given quality product on one side of the line but not the other might be tough. Manufacturers' sole option for reducing producer proliferation and the possibility of dilution of the GI's brand property is to limit the region associated with the GI. Establishing and enforcing GI classification in the European Union, for example, may oblige non-EU businesses to remove references to these GI descriptors from their marketing materials, undermining a key source of brand value for these businesses (Rosas, 2020, Gan, 2020; Situmeang & Murniarti, 2021; Rahmah, 2018; Zappalaglio, 2021). Global food firms may have registered such names in their respective countries in certain cases. It's worth noting that companies may use geographical links in their brand positioning that aren't registered as trademarks. Finally, adopting GI strategies might cause issues for existing businesses that have used GIs "indiscriminately" to advertise their products (e.g., Chinese cuisine, Italian dressing), as well as multinational food companies that have utilised such designations to identify a product class. (Punchihewa, 2020; Styvén et al., 2020; Panda et al., 2020; Marescotti et al., 2020; Fusté-Forné, 2020; Başaran, 2021; Jaelani et al., 2020; Majerčáková & Greguš, 2021; Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2019).

Conclusion

Without experiencing the regional specialties, gastronomy tourism in any destination's culture is incomplete. It's vital to provide regionally defined things from that location and area with the same degree of distinct quality and flavour as what's available locally. In an information-based economy, understanding Geographical Indications is crucial for the growing and ongoing growth of local and rural gastronomic tourism to cater to a diverse variety of visitors and clients. Geographical Indications are currently seen as a new kind of intellectual property that may be used to gain a competitive edge in gastronomic tourist marketing and branding. Each area has a valid claim to recognition in culinary tourism, which must be protected under GIs. Economically and politically, geographic cues are becoming more important. Gastronomy tourism is gaining traction in both developed and developing countries, with the potential to boost national and rural tourist profits. They've seen the GIs' revenue-generating potential in gastronomic tourism. Geographical indicators are also linked to culinary tourism since they attract international visitors and support the survival and growth of local tourist communities. It is critical to improve the usage and preservation of GIS for branding and marketing edge in order to guarantee the right growth of domestic culinary tourism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Management & Science University for the support on this publication.

References

Ahmad, A., Jamaludin, A., Zuraimi, N.S.M., & Valeri, M. (2021). Visit intention and destination image in post-Covid-19 crisis recovery. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(17), 2392-2397.

Başaran, B. (2021). Perceptions, attitudes and behaviours of consumers towards traditional foods and gastronomy tourism: The case of rize. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 8(3), 1752-1769.

Birch, D., & Memery, J. (2020). Tourists, local food and the intention-behaviour gap. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 53-61.

Čehić, A., Mesić, Ž., & Oplanić, M. (2020). Requirements for development of olive tourism: The case of Croatia. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 26(1), 1-14.

Celebi, D., Pirnar, I., & Eris, E.D. (2020). Bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship in gastronomy tourism. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 68(1), 58-67.

Çetin, B. (2021). Gastronomy tourism. Tourism Studies and Social Sciences, 16.

de Almeida, A.R., & Carls, S. (2021). The criteria to qualify a geographical term as generic: Are we moving from a European to a us perspective?. IIC-International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 52(4), 444-467.

Defossez, D.A.L. (2017). Global regulation of international intellectual property through agreement on trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS): The European Union and Brazil. Journal of Law and Regulation, 3(2), 131-160.

Delimatsis, P. (2021). A partnership of equals? ‘Deeper’ economic integration between the EU and Northern Africa. European Foreign Affairs Review, 26(4).

Derek, M. (2021). Nature on a plate: Linking food and tourism within the ecosystem services framework. Sustainability, 13(4), 1687.

Dewalska-Opitek, A., & Hofman-Kohlmeyer, M. (2021). Players as prosumers-how customer engagement in game modding may benefit computer game market. Central European Business Review, 10(2).

Dutfield, G., & Suthersanen, U. (2019). Traditional knowledge and genetic resources: Observing legal protection through the lens of historical geography and human rights. Washburn LJ, 58, 399.

Dutta, P., Choi, T.M., Somani, S., & Butala, R. (2020). Blockchain technology in supply chain operations: Applications, challenges and research opportunities. Transportation Research Part e: Logistics and Transportation Review, 142, 102067.

Duxbury, N., Bakas, F.E., Vinagre de Castro, T., & Silva, S. (2021). Creative tourism development models towards sustainable and regenerative tourism. Sustainability, 13(1), 2.

Fernández-Zarza, M., Amaya-Corchuelo, S., Belletti, G., & Aguilar-Criado, E. (2021). Trust and food quality in the valorisation of geographical indication initiatives. Sustainability, 13(6), 3168.

Friedmann, D. (2020). Grafting the old and new world: Towards a universal trademark register that cancels generic IGO terms. In Wine Law and Policy (pp. 311-345). Brill Nijhoff.

Fusté-Forné, F. (2020). Savouring place: Cheese as a food tourism destination landmark. Journal of Place Management and Development.

Gan, R. (2020). “Pure Michigan” and “Napa Valley 100%”: Is protection of american origin wines as geographic indications on fertile ground?. In Wine Law and Policy (pp. 392-414). Brill Nijhoff.

Ghouri, A.M., Mani, V., Jiao, Z., Venkatesh, V.G., Shi, Y., & Kamble, S.S. (2021). An empirical study of real-time information-receiving using industry 4.0 technologies in downstream operations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 165, 120551.

Ianioglo, A., & Rissanen, M. (2020). Global trends and tourism development in peripheral areas. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 520-539.

Jaelani, A.K., Handayani, I.G.A.K.R., & Karjoko, L. (2020). Development of tourism based on geographic indication towards to welfare state. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(3), 1227-1234.

Jarma Arroyo, S.E., Hogan, V., Ahrent Wisdom, D., Moldenhauer, K.A., & Seo, H.S. (2020). Effect of geographical indication information on consumer acceptability of cooked aromatic rice. Foods, 9(12), 1843.

Katt, F., & Meixner, O. (2020). A systematic review of drivers influencing consumer willingness to pay for organic food. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 100, 374-388.

Ketter, E. (2020). Millennial travel: tourism micro-trends of European Generation Y. Journal of Tourism Futures.

Kuruk, P. (2020). Traditional Knowledge, Genetic Resources, Customary Law and Intellectual Property: A Global Primer. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lee, C.K., Ahmad, M.S., Petrick, J.F., Park, Y.N., Park, E., & Kang, C.W. (2020). The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100500.

Liu, C.H., & Jiang, J.F. (2020). Assessing the moderating roles of brand equity, intellectual capital and social capital in Chinese luxury hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 139-148.

Lu, L., Nguyen, R., Rahman, M.M., & Winfree, J. (2021). Demand Shocks and Supply Chain Resilience: An Agent Based Modelling Approach and Application to the Potato Supply Chain (No. w29166). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lucier, G., & Parr, B. (2020). Vegetable and Pulses Outlook. United States Department of Agriculture. April.

Majerčáková, D., & Greguš, M. (2021). The analysis of the investment opportunities into the wine. In Eurasian Business and Economics Perspectives (pp. 189-201). Springer, Cham.

Marescotti, A., Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F., Edelmann, H., Belletti, G., Broscha, K., Altenbuchner, C., Penker, M., & Scaramuzzi, S. (2020). Are protected geographical indications evolving due to environmentally related justifications? An analysis of amendments in the fruit and vegetable sector in the European Union. Sustainability, 12(9), 3571.

Motari, M., Nikiema, J.B., Kasilo, O.M., Kniazkov, S., Loua, A., Sougou, A., & Tumusiime, P. (2021). The role of intellectual property rights on access to medicines in the WHO African region: 25 years after the TRIPS agreement. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-19.

Nurani, N., Nurjanah, R., & Prihantoro, I. (2020). Competence of human resources of small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) of West Java through intellectual property rights (IPR) protection in the COVID-19 pandemic era. PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(10), 3878-3896.

Özdemir, B.P. (2018). Branding a millennia-old Turkish city: Case of Gaziantep. Ankara Üniversitesi İlef Dergisi, 5(2), 121-140.

Pacult, F.P. (2021). Buffalo, barrels, & bourbon: The story of how buffalo trace distillery became the world's most awarded distillery. John Wiley & Sons.

Panda, T.K., Kumar, A., Jakhar, S., Luthra, S., Garza-Reyes, J.A., Kazancoglu, I., & Nayak, S.S. (2020). Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. Journal of Cleaner Production, 243, 118575.

Pavlidis, G., & Markantonatou, S. (2020). Gastronomic tourism in Greece and beyond: A thorough review. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 21, 100229.

Payandeh, E., Allahyari, M.S., Fontefrancesco, M.F., & Surujlale, J. (2020). Good vs. fair and clean: An analysis of slow food principles toward gastronomy tourism in Northern Iran. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 1-20.

Punchihewa, N.S. (2020). Branding of tourism-related products and services for a competitive advantage in Sri Lanka: An intellectual property perspective.

Rahmah, M. (2018). The protection of geographical indication for agricultural development: Challenges for ASEAN.

Ranjan, P. (2021). Trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights waiver at the world trade organization: A bit of a challenge. Available at SSRN.

Rejeb, A., Rejeb, K., Simske, S., & Treiblmaier, H. (2021). Blockchain technologies in logistics and supply chain management: A bibliometric review. Logistics, 5(4), 72.

Richards, DG (2020). Intellectual property rights and global capitalism: The political economy of the TRIPS agreement. Routing.

Richards, G. (2021). Evolving research perspectives on food and gastronomic experiences in tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management.

Rosas, R. (2020). A comparative study of trademarks: USMCA (US-Mexico-Canada Agreement) and NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement). BU Int'l LJ, 38, 38.

Sayuti, Y., Albattat, A., Ariffin, A., Nazrin, N., & Silahudeen, T.N.A.T. (2020). Food safety knowledge, attitude and practices among management and science university students, Shah Alam. Management Science Letters, 10(4), 929-936.

Schipper, F., Tchoukarine, I., & Bechmann Pedersen, S. (2018). The history of the European travel comission. Brussels: European Travel Commission.

Seyitoğlu, F., & Ivanov, S. (2020). A conceptual framework of the service delivery system design for hospitality firms in the (post-) viral world: The role of service robots. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102661.

Silva, V., & Paul, N. (2021). Potential impact of earthquakes during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Earthquake Spectra, 37(1), 73-94.

Situmeang, T., & Murniarti, E. (2021). Asean attitudes toward patent protection of the covid-19 vaccine versus humanitarian interests. Jurnal Hukum dan Peradilan, 10(2), 255-276.

Sottile, F., Massaglia, S., & Peano, C. (2020). Ecological and economic indicators for the evaluation of almond (Prunus dulcis L.) orchard renewal in Sicily. Agriculture, 10(7), 301.

Styvén, M.E., Mariani, M.M., & Strandberg, C. (2020). This is my hometown! The role of place attachment, congruity, and self-expressiveness on residents’ intention to share a place brand message online. Journal of Advertising, 49(5), 540-556.

Süess, A. (2012). Feta and chablis-what's in a name?: systems of GI protection under the aspect of genericness.

Supriatna, A.D., Tresnawati, D., Kurniadi, D., & Cahyana, R. (2021). Web-based geographic information system for mapping religious tourism object. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1098, No. 3, p. 032071). IOP Publishing.

Török, Á., Jantyik, L., Maró, Z.M., & Moir, H.V. (2020). Understanding the real-world impact of geographical indications: A critical review of the empirical economic literature. Sustainability, 12(22), 9434.

Vandecandelaere, E., Teyssier, C., Barjolle, D., Fournier, S., Beucherie, O., & Jeanneaux, P. (2020). Strengthening sustainable food systems through geographical indications: Evidence from 9 worldwide case studies. Journal of Sustainability Research, 4(3).

Visković, N.R., & Komac, B. (2021). Gastronomy tourism: A brief introduction. Acta Geographica Slovenica, 61(1), 95-105.

Yalin, G. (2021). An overview of gastronomy tourism. Tourism Studies and Social Sciences, 134.

Yongxun, Z., & Lulu, H. (2021). Protecting important agricultural heritage systems (IAHS) by industrial integration development (IID): Practices from China. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 12(4), 555-566.

Zappalaglio, A. (2021). Sui generis, bureaucratic and based on origin: A snapshot of the nature of EU Geographical Indications. In Intellectual Property as a Complex Adaptive System. Edward Elgar Publishing.