Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Governance of the waste management in Croatia

Ana-Maria Boromisa, Institute for Development and International Relations

Natalija Golubovac, Safege d.o.o.

Natasa Vetma, World Bank

Citation Information: Boromisa, A., Golubovac, N., & Vetma, N. (2022). Governance of the waste management in Croatia. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S4), 1-18.

Abstract

Croatia has difficulties to comply with waste management regulations. Not only that huge investments are necessary, but the challenge are also weaknesses of governance structures and unclear separation of competences. This paper identifies regulatory and institutional bottlenecks for waste management system in Croatia and provides recommendations on how to tackle them. It provides recommendations to stakeholders involved in implementing the Waste Management Plan, including their obligations and duties under the current regulation, and addresses opportunities for easier project implementation. In addition, it proposes an institutional and organizational set-up for reaching EU waste management objectives, including multi-institutional implementation bodies or special-purpose vehicles. Due to the delays in implementation of the Waste Management Plan and the changes underway to EU legislation, this paper also looks into the formation and structure of a permanent negotiation team to discuss/negotiate an action plan for avoiding infringement procedures as well as facilitating changes in relevant EU directives and their future application to Croatia.

Keywords

Governance, Croatia, Waste Management, EU

Introduction

Thus far, Croatia has failed to comply with EU waste regulations in a timely manner. There are already 19 legal proceedings against Croatia related to waste management (representing 21.5 percent of all EU proceedings against Croatia); in 2021, the year for which the latest data is available, six new waste-related decisions have been adopted. The transition period to bring waste disposal (landfills) into compliance as defined in the Accession Treaty (in accordance with EC Directive 1999/31/EC) expired at the end of 2018. Based on plans, Croatia was expected to be in compliance with this Accession Treaty obligation by 2021, but is facing significant delays (CCA, 2015).

Compliance entails additional costs (for transitional solutions) on top of the necessary investments that have to be made. According to the national Waste Management Plan, the total cost of remediation and closure of existing non-compliant waste disposal sites was estimated at HRK975 million (or EUR130 million). Further expenses will have to be considered for the construction of the additional landfill capacity (required for compliance with EU standards) and for investments in waste collection and waste transport equipment.

By conservative estimates, the infringement penalties could be steeper than the combined cost of the required investments (remediating and closing non-compliant disposal sites, new landfill capacity, collection and transport equipment). However, if some level of progress is achieved, penalties could be less (at least at the moment of their issuance). Based on an analysis of previous verdicts, this scenario of potentially lower penalties relies upon the premise that a verdict involving penalties would only be issued in 2023 and further assumes that the closure of some operating landfills has been accomplished by then. An estimated sentence would then consist of a lump sum of EUR10 million and a daily penalty of EUR42,000. Thus, for the period from 2019 to mid 2023, the amount of daily penalty charged amounts to EUR68.9 million. This amount, obviously, is still significant in comparison to the overall cost of investments, but substantially lower than the amount of penalties that would apply if less progress was reported. However, these cost sums do not include court costs and representation costs, which will continue to rise until requirements are met. The verdict could also affect the ability of Croatia to use EU funds in the this Programming Period (2021-2027).

Poor governance at both the central and local government levels has been identified as a core problem in reaching EU waste management objectives. In addition to a lack of willingness to change, regulatory and institutional structures are hindering implementation of the national Waste Management Plan. Inertia in passing regulations and poor inter-institutional cooperation are some of the reasons for delays in implementing the national WMP and enhancing the waste management system. Clear rules as well as their consistent application are needed for the successful implementation of NWP measures, especially at the local and regional levels (European Commission, 2016).

Background

The European Commission 2014-2020 Partnership Agreement with Croatia determined that "improvements in the communal sector are necessary since the current institutional system for waste and water management is fragmented and inefficient (with more than 150 companies are dealing with water and more than 200 with municipal waste).” Consolidation in the communal sector would primarily involve increasing the efficiency of service providers, including capacity-building measures, organizational support to new/existing communal service providers, alignment with the requirements of Directives, and providing capacity to enable/support the management of infrastructure after project completion. Consolidation is needed in order to secure adequate availability of services across Croatia, provide basic prerequisites for a more balanced regional development, and secure efficient management of resources, as well as the protection of the natural environment.”

The problems in Croatia’s waste management system are not new, and most of the concerns identified in the 2005 Waste Management Strategy (OG 130/2005) continue to be an issue, which indicates the existence of poor governance and lack of political will to establish efficient waste management systems. Besides the inefficiency of infrastructure to meet national needs and comply with the EU directive, problems remain concerning a) a regulatory system that is inadequate or partially applied; b) insufficient awareness by legal entities that the waste they generate is their responsibility; c) insufficient education of citizens and the employees of waste management companies; d) insufficient knowledge of EU waste management practices and trends; e) a data delivery system that does not meet requirements; f) decisions on siting of landfills and other waste management facilities and infrastructure; g) lack of project documentation and required permits and unresolved property rights in both existing and potential locations of facilities and installations; h) insufficient application of market principles and the "polluter pays" principle; and i) difficulties in obtaining the cooperation of LGUs in order to establish the infrastructure and public services necessary for efficient and modern waste management systems (European Commission, 2017).

Institutional Framework

Waste management responsibilities in Croatia are established by the Sustainable Waste Management Act. The main central government stakeholders are the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development, Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds; the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund (EPEEF). Previosuly, relevant role had the Croatian Agency for Environment and Nature (CAEN), but since 2018 it became part of the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development. Waste management implementation is decentralized predominantly to local government units, although regional government units play a role table 1, 2.

| Table 1 Central Government |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatian Parliament and Government | Creates policies and strategies on waste management; establishes an inter-departmental coordination body for harmonization of waste management policies; establishes an appropriate economic, financial, and regulatory framework for the implementation of the Strategy; facilitates selection of locations for all necessary facilities and installations; conducts or gives support to other activities that are necessary for the improvement of the integrated waste management system. | |||

| Ministry of Ecomnomy and Sustainable Development | Prepares laws, strategies, and a waste management plan; produces a report on the state of the environment; approves projects based on environmental impact assessments; issues licenses for hazardous waste management and thermal treatment of waste; issues concessions for managing special categories of waste; implements hazardous waste management measures; and inspects and supervises the implementation of laws and regulations, as well as oversees the work of enforcement bodies. | |||

| Ministry of Regional Develop-ment and EU funds | Sets priorities, and prepares strategic and operational documents, for use of EU funds. | |||

| The Environ-mental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund (EPEEF) | The central source for collecting and investing extra-budgetary resources into programs and projects that protect nature and the environment, energy efficiency and renewable energy sources. In the system of management and control of the utilization of EU structural instruments in Croatia, EPEEF performs the function of Intermediate Body level 2 for the specific objectives in the fields of environmental protection and sustainability of resources, climate change, energy efficiency, and renewable energy sources. In the area of waste management, EPEEF’s jurisdiction includes managing fees and the operation of management systems for special categories of waste, incentive fees for reducing the amount of mixed municipal waste, municipal waste disposal fees, and construction waste disposal fees. | |||

| Croatia Agency for Environment and Nature (CAEN) | Collects and aggregates data and information on the environment and nature; monitors the implementation of environmental and nature policy and sustainable development; and conducts professional nature conservation activities. For waste management, CAEN provides information on waste; collects, aggregates and processes waste data; ensures and allows access to information and data on waste; develops and coordinates the information system for waste management and maintains a reference center with databases. | |||

| Table 2 Local Government |

|

|---|---|

| Regional Government Units - Counties | Responsible for preparing reports on the implementation of national and local waste management plans and their submission to CAEN (must ensure that conditions and implementation of measures are being met); determines locations for waste management facilities (WMCs) in county spatial plans; provides input for the information system in a timely manner and without compensation; issues licenses for the management of non-hazardous waste, with the exception of licenses for thermal treatment processes, and ensures the conditions and implementation of measures to manage non-hazardous waste. |

| Local Government Units – Cities and Municipalities (plus municipal waste companies) | Determines locations (through development plans) for waste management facilities and installations; adopts local waste management plans in line with the national waste management plan; organizes collection and safe disposal of municipal waste in accordance with the WMP; enables separate collection of waste; and organizes transport to WMCs. |

Institutional Challenges

Challenges - Local Level

Regardless of the sector, Republic of Croatia faces general institutional weaknesses. With a decentralized system, such weaknesses are even more evident; in the waste management sector, 556 LGUs implement the national waste management plan.

The greatest number of WMP measures fall under the responsibility of LGUs. LGUs are obliged to ensure that the conditions and implementation of national waste management measures are met in their area. With the average size of an LGU at 6,000 inhabitants (excluding the City of Zagreb), inefficiencies and lack of capacity are almost guaranteed at that level in a decentralized system. About 60% of LGUs have their own WMPs in line with Law on Sustainable Waste Management 1.

Due to variations in size, different administrative bodies carry out waste management activities in these 556 LGUs; often it is the administrative departments. They adopt local waste management plans, determine waste site locations in spatial plans, implement municipal waste management measures, and provide data on waste management (HAOP, 2018).

Financially, the most demanding measures from the national WMP should be co-financed by the LGUs, which is an obstacle to the timely implementation of those prescribed measures. Many LGUs have financial and technical limitations in meeting their required obligations for infrastructure construction, preparation of planning documentation, implementation of information and educational activities. Their lack of capacity makes LGU preparation of study and project documentation difficult, as well as the quality of their public procurement (e.g., drafting procurement documentation, and works and services in the area of waste management). Capacity is equally important for a successful application for co-financing of projects from the state budget or through EU funds (HAOP, 2018).

Since 2013, RGUs are no longer obliged to prepare regional waste management plans and thus, have lost both technical and financial capacity needed in the sector. Instead, since that time the 556 LGUs independently prepare waste management plans in alignment with the national waste management plan. The RGU role now is to determine whether the LGUs’ waste management plans are in accordance with the law and if so, provide their consent to the plans (Government, 2017).

Planning for WMCs without RGU waste management plans risks the sustainability of the system during operations. Most of the municipal waste management is the responsibility of the LGU; however, WMCs are the responsibility of the RGU while the final decisions on locations, number of centers, technology used, and capacity are made at the state level. The RGU also prepares spatial plans with which LGU plans must align. There is inadequate co-operation in planning between RGUs and LGUs. On average, an RGU covers 28 LGUs; without the coordination of a regional WMP and the legal mandate to coordinate, there is no system of WMCs, but fragmented, more or less successful efforts that do not contribute to an efficient waste management system (Government, 2017).

The role of the RGU in the planning and implementation of a waste management system, especially as related to municipal waste, is formal, lacking the plans2 and sufficient technical and financial capacity. In order to improve the process of implementation, the formal organization needs to be aligned with its capacities and clearly define the competencies (as well as implementing instruments). Cooperation is needed among LGUs in order to establish a functional waste management system (e.g., in establishing WMCs) that exceeds their capacities. Although legislation permits LGUs to use contracts to ensure the joint implementation of waste management measures, in a majority of LGUs the capacity for such action is questionable. Cooperation among different LGUs is required, e.g. given the spatial characteristics, the City of Zagreb and Zagreb County should use the same WMC.

This requires agreement between the two counties and their municipalities (35 in Zagreb County and the City of Zagreb), which have very different institutional and financial capacities. The agreement for Piskornica requires agreement among six counties and more than 100 municipalities. Thus, RGUs should play a more significant role in the planning of regional systems, but such a role should not remain simply formal.

Challenges - Central Level

On a central government level, the situation with capacity is better, but the lack of coordination creates even more systematic problems in waste management, including regulatory gaps, delays in implementation, and inadequate waste management solutions.

The MoESD’s Regulatory Role

A lack of MoESD administrative capacity is responsible for the partial harmonization of Croatian legislation with the EU acquis communautaire in the field of waste management, as well as the partial improvement of the legislative framework. If fully realized, the latter would ensure the preconditions for the establishment of an integrated waste management system 3.

MoESD Participation in the Creation of EU Policies

Compared to its proactive approach during the EU negotiation period (pre-accession period), Croatia and more specifically the MoESD, is not sufficiently participating nor is it effective in the development of EU policy. Since Croatia’s accession to the EU in 2013, its role in the creation of strategic documents has formally changed. Being a full EU member, Croatia has the opportunity to actively participate in policy-making and the creation of European policies. However, institutional weaknesses limit this role, and Croatia is not using this opportunity. While there were dedicated negotiating teams during the pre-accession period (whose primarily role was to negotiate transition periods as necessary), now such teams, which could have impact on EU policies, no longer exist to any real extent. In a majority of the cases, these roles are performed by capable individuals; however, they have insufficient time to properly execute this role, there is no policy coordination at the level of the MoESD.

Transposition of Legislation

There has been a significant deterioration in the transposition of European policies. Waste management is the most problematic sector, in 2021, 22% of all procedures related to waste.4 In 2017, Croatia hase the EU member state with fifth highest transposition deficit, showing that Croatia has great difficulties in monitoring the timely transposition of the directives.5 Croatia has speeded up the process since, and int 2020 it has only 2 overdue directives, both in environment sector. However, there is an issue with conformity and the conformity deficit has reached 1.9% in 2020 (up from 0.9% in 2019)

Ambitious Targets

Croatia sets more ambitious national targets than the of EU sets. Considering conformity deficit, it shows a poor level of decision-making and a lack of awareness of the realistic capacities of implementing entities. There are many examples: the Treaty concerning the accession of the Republic of Croatia to the European Union allowed a transitional period for compliance, requiring that all existing landfills in Croatia comply with the requirements of the Lnadfill Directive by 31 December 2018; however, Croatia opted for an earlier completion date of December 31, 2017. Today, as the EU deadline expired only two WMCs have been constructed while approximately 130 non-compliant landfills are in ooperation, which are the reason for an infringement procedure. As another example, Croatia has set a target of a 5% reduction in the total amount of municipal waste generated. European regulations do not set a quantitative target, but propose measures to prevent the generation of waste. The amount of generated municipal waste is lower in Croatia than the EU average, but it is increasing and thus, calling into question the country’s ability to achieve the target. Moreover, the quantitative target set accordingly does not take into account issues such as demographic changes, the impact of economic growth, or tourism, which could significantly affect achievement of the target compared to the implementation of waste management measures. Therefore, the justification for this indicator is questionable.

Emergency Procedures

Very often waste legislation is not coherent or harmonized with other legislation- especially in the case of regulations of similar standing (e.g., acts and regulations), the implementing and strategic documents, and various decisions approved by the Government and the Parliament. Some of those are not originating through regular procedures but are being passed as emergency procedures, which affects the quality of preparation and impacts implementation. This leads to policies that are not well thought-out, policies that lack sufficient consultation, or policies where the impact has not been evaluated properly. Most likely this is a result of inadequate capacity and a lack of coherence within MoESD.

Examples include Amendments to the 2017 Sustainable Waste Management Act that were passed as an urgent procedure to address EU legal requirements that were violated (violations No. 2016/0637 and 2015/2160; transposition was to be done by 2015) and eliminate the possibility that the EU would impose substantial financial sanctions against the Republic of Croatia.6 Through the same amendment, the deadline for a ban on waste disposal in non-compliant landfills came into harmony with the Croatian Treaty of Accession Agreement.7 The amendment addresses the possibility of violations of the EU directive, but does not address the problems already identified in implementation.

Unrealistic Implementation Deadlines

Deadlines for the preparation and implementation of new regulations are not realistic, leading to poor preparation and requiring frequent changes. For example, the Ordinance on Packaging and Packaging Waste has been changed 10 times in 12 years; also, the date the ordinance is to come into effect - immediately after publication in the Official Gazette is unrealistic. With such frequent changes, adjusting to new provisions is problematic. This example also illustrates how problems are not tackled systematically, but ad hoc and one by one.

Legislative and regulatory changes are not systematic, nor do they solve identified problems or contribute to clear targets. According to the Sustainable Waste Management Act (OG 94/13), for example, the service provider for collection of mixed municipal waste and biodegradable municipal waste is obliged to submit a work report for the past year to the representative body of the LGU by January 31 of the current year. By amendments to the Act made in 2017 (OG 73/2017), the submission deadline has been moved to March 31. No reason has been provided for the change in deadlines.

Some of the deadlines are met only formally and are not seen in implementation. Based on adoption of the Regulation on Municipal Waste Management, LGUs introduced the billing system for the collection and processing of mixed and biodegradable municipal waste by quantity starting with Q4 2017 (the deadline for the decision was 1 February 2018). Most of the LGUs prepared decisions on billing within the planned timeline. However, the decision cannot be implemented in many cases because there is no infrastructure for separate collection and processing of mixed municipal waste. In order to support implementation, separate containers should be provided where needed; justification for the collection should be prepared; and the system to monitor the transport of municipal waste should use available and efficient (cheap) technologies for tracking the truck route, the position of containers, their filling, and so on.

Ad HOC Policy Decisions

Some decisions on amending the legislation are made ad hoc, without planning, or justification. The obligatory training program, for example, was introduced in 2015 under the Sustainable Waste Management Act and cancelled less than a year into implementation. According to the Sustainable Waste Management Act, waste managers (companies with more than 50 employees) had to be certified for waste management by a training program approved by the MoESD. The certificate was to be renewed every five years, but in less than a year after approval, this training program was cancelled; specifically, the Ministry adopted the Program in 2015 (OG 77/2015), and the decision to discontinue it occurred in 2016 (OG 20/2016). The rationale given for such an action was that this approach did not represent comprehensive education on waste management since it was limited based on company size. In addition, it was considered to be a parafiscal fee since the obligation was defined by the number of employees rather than by the amount of waste produced. No substitute training programs have been envisaged since.

Weaknesses of Implementing Regulations

Passage of the implementing regulations anticipated by the Sustainable Waste Management Act is significantly overdue. Among the needed regulations are the Waste registry, Regulation on waste oils, and Regulation on laboratories. Delays in passing these regulations have resulted in partial implementation of the law and parallel use of implementing regulations under the old waste management act, which in some instances conflict with the new act.

The key implementing documents – the national WMP and the Implementation Decision on WMP - conflict in many areas. For example, according to the WMP, a decision to terminate or continue the operation of a landfill (if designed to be compliant after December 31, 2018), as well as the decision to bring the landfill or a part of the landfill (active area/cassette) into compliance through remediation, is the responsibility of the operator managing the landfill. According to the Implementation Decision, LGUs are responsible for the preparation of a closure plan for non-hazardous waste landfills. This is a conflict since landfill operators are municipal utility companies that manage municipal waste and are in most cases established by LGUs.

Planning Weaknesses

Planning weaknesses (in terms of deadlines, costs, order of measures, and assessment of their effects) indicate the lack of institutional capacity to design and implement policies. There are no clear criteria to serve as the basis on which the investments are planned, which is particularly seen in the different documents in force with regard to WMCs and their capacity, spatial coverage, and planned costs.

As defined by the Waste Act, the WMC is a facility of state importance. Activities related to the WMC are carried out by a company owned by the RGU and/or the LGU. These activities and affairs can be carried out by the Republic of Croatia in accordance with the law regulating concessions, i.e., the law governing public-private partnerships, but as an exception. Funds for establishing WMCs are secured through the EPEEF and from other sources. The Implementation Decision leaves the possibility that WMCs, other than those already in implementation (Bikarac and Biljane donje), may be funded by LGUs and RGUs, EPEEF, the EU, private investment, and public private partnerships. However, this indicates a lack of definition in the structure of financing.

The planning period calls for the preparation and construction of seven WMCs in five years, although the EU funds co-financing method has not been determined. Unrealistic deadlines indicate weaknesses in planning and inadequate institutional capacity. The WMP and ID recommends achieving the targets and completing the construction of the WMCs during the current programming period (i.e., by the end of 2022), except for the City of Zagreb, for which beginning of construction is foreseen for 2020, and WMC Lučino Razdolje, for which a decision on establishing the center is foreseen by 2018. Past experience shows this timeline to be unrealistic. For example, for the Kastijun WMC, EU co-financing was approved in 2011, the co-financing agreement was revised in 2013, and the construction was not completed in the 2007-2013 programming period; indeed, it had not been completed by December 31, 2016, when EU funding ended. The agreement between the Ministry, the EPEEF, and Istria County on cost-sharing was concluded in 2017. The EPEEF and the Ministry each assumed 40% of the costs, and the County the remaining 20%. In other words, construction of the Kastijun WMC was not completed within five years of the co-financing being secured. The national WMP does not include individual cost estimates for the most financially burdensome investments (e.g., construction of WMCs, remediation of individual landfills), so their justification cannot be assessed.

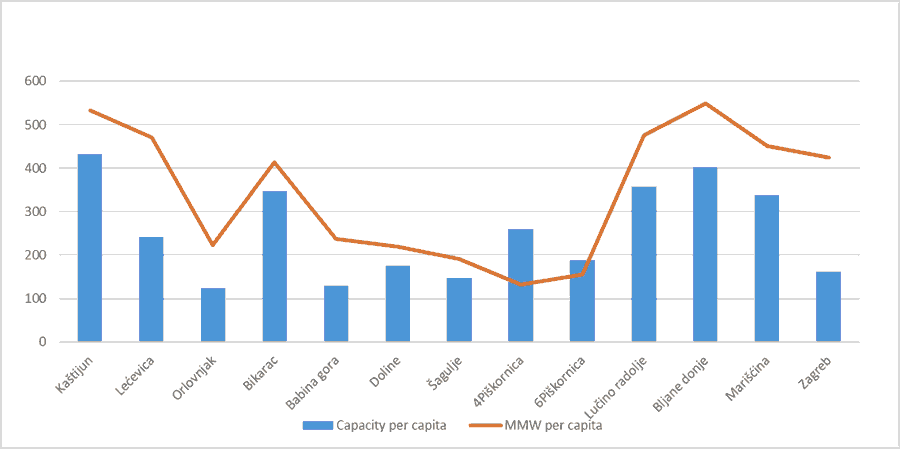

Large variations in the planned capacities of WMCs have been identified relative to the current quantities of mixed municipal waste (see Figure 1 above) with a significant difference in unit costs.8 While the NWP anticipates a significant reduction in the amount of mixed municipal waste, the planned capacity of Piskornica exceeds present needs. The excess capacity was even more significant when the jurisdiction of Piskornica WMC was planned for four counties (through the ID, it now covers six counties).

Further examples of planning weaknesses, are the procurement of containers to provide a mixed and biodegradable municipal waste collection service at LGU level and the procurement of sorting plants, which should contribute to achieving the separate collection target. To apply for containers, LGUs should have their WMP prepared and approved, while for sorting plants such a requirement is not a precondition; rather, only a feasibility study is required. Feasibility studies are appropriate for defining the critical variables of a particular project. However, sorting plants should contribute to the overall WM system. Simultaneous applications for a large number of sorting plants make it impossible to identify systemic options, which then affects the choice of a solution. Having a planning document (WMP) prepared at the LGU level and approved by the relevant RGU competent authority would contribute toward better system planning. A more holistic solution would be to develop RGU waste management plans that could estimate the needs for the sorting plants per county or per WMC.

The Role and Capacity of the EPEEF

The EPEEF provides technical and financial support to waste management investments and as such plays a key role in implementation of the national WMP. Technical expertise exists in the EPEEF, but it is not structured and not used adequately. The EPEEF should also provide financial support to the national co-financing of EU-funded projects. In the previous OP period, the EPEEF’s designated share in the co-financing was around 25%. However, due to the significant financial shortfalls of the EPEEF, which subsequently reduces its role in co-financing of waste management investments, the planned contributions of the EPEEF have been reduced. This will inevitably contribute to delays in the implementation of the national WMP.

The EPEEF’s scope is extremely broad. The EPEEF partly performs a role as a public authority, but also performs activities that could be carried out by commercial entities. The Croatian Competition Agency advises for the EPEEF to regulate the waste management system as a body with public authority whose purpose is ensuring the general (economic) interest in the protection of the environment, performs only regulatory work as specified in regulations (including keeping records, registers, issuing permits, and supervision). Market-based activities, as a rule, should be performed by market-based entrepreneurs. This ensures a system in which a particular entity or a legal entity with public authority does not serve as a market participant while simultaneously carrying out tasks related to supervising or issuing licenses to market stakeholders.

In cases where it is permissible for a particular entity (legal person) to exercise public authority on the basis of exclusive rights as determined by regulation, while at the same time performing a service in the free market, it is necessary to act with special care so there would be no disruption of competition in that segment of the free market.

In this regard, a bylaw should be used to set the accounting separation (unbundling) of the activities of public and commercial services. In doing so, it is also necessary to clearly state the principles of cost accounting according to which separate accounts are kept so as not to transfer funds from regulated to market activities, or excessively finance or unnecessarily use the budget, i.e., taxpayers' funds.9

No functional mechanisms exist for controlling and collecting legally prescribed fees in waste management, and some fees cannot be charged due to the failure to adopt a regulation prescribed by the Sustainable Waste Management Act.

EPEEF revenue is planned according to its source (types of fees), while its expenditures are planned based on programs, projects and activities. The expenditures are not related to the sources of funding. In several reports (2015, 2010), the State Audit requested the adoption of a multi-annual program plan for the EPEEF's work. Taking into account the dynamics mentioned above and the institution’s evident financial difficulties, a restructuring of the EPEEF should be undertaken, which should be based on a well-prepared restructuring plan. The preparation of the restructuring plan should be closely tied to an analysis of the effectiveness of currently prescribed fees paid to the EPEEF as well as their level and purpose. State Audit Office and Competition Agency recommendations to fix the system are ignored.

Given the technical capacity of the EPEEF, it provides necessary technical support to LGUs and RGUs in their implementation of national WMP measures.

Unclear Competencies and Responsibilities

The competencies and responsibilities of individual bodies are not clear, nor aligned with the capacity needed for implementation (administrative, organizational and financial).

According to the Implementation Decision, the MoESD is the co-holder of a measure for the construction of WMCs, but not the source of funding. In order to participate as a co-holder in implementation of the measure, the MoESD should ensure an adequate implementation capacity (e.g., identify the competent officer, ensure cover for labor costs). An organizational solution that anticipates a co-holder who does not provide means for implementing the measure jeopardizes the implementation capacity.

For some WMCs, a portion of a county is defined as the holder of the measure (e.g., for Biljane donje, the WMC holders are Zadar and part of Lika-Senj County, the co-holder is MoESD). A portion of a county cannot be a legal entity; moreover, in cases where one county participates in two WMCs, financing and management models are not defined.

Non-Harmonized or Conflicting Key Planning Documents

There is a lack of coherence between planning and implementation documents. The planning documents define different deadlines for the same actions, yet all in enacted. The Waste Management Plan defines deadlines for the application of charges for collection and processing of mixed and biodegradable municipal waste by quantity; nevertheless the implementing regulation was delayed thus preventing the implementation. Similarly, the national WMP defines a shorter deadline for the application of the landfill fee than the deadline in the National Reform Plan (NRP). The NRP also changes the title and the content of the act introducing the landfill fee. However, both documents were passed by the same Government.

The financial planning for the same waste management measures differs in the document passed by the same bodies. In less than a year, the Government and the Parliament adopted documents that specify in different ways the financing of WMP implementation. The WMP, which was adopted by the Government, anticipates a considerably higher investment by the EPEEF over the next few years than contained in the actual 2018 Financial Plan (with projections for 2019 and 2020) to which the Parliament has consented.

The Act on Sustainable Waste Management differs from the national WMP and ID of the Waste Management Plan concerning the content of LGU WMPs. The Act prescribes the minimum content of the LGUs WMP and the City of Zagreb WMP. It includes 12 activities (see Table 1 below), including measures on requirements to achieve the targets of reducing or preventing waste generation; data on the types and quantities of waste produced; separately collected waste; disposal of municipal and biodegradable waste; and the achievement of targets.

The WMP and the Implementation Decision identify two specific measures that should be contained in LGU WMPs. The first relates to "inclusion of waste prevention measures in LGU Waste Management Plans," and the indicators to assess realization are 556 plans including measures to prevent waste generation. The second relates to "monitoring the share of biodegradable waste in mixed municipal waste." The indicator to assess realization is the number of LGUs that follow these shares on an annual level.

The counties should consent to LGU WMPs after checking the consistency of the LGU waste management plan with the Sustainable Waste Management Act, the Waste Management Plan of the Republic of Croatia, and regulations passed on the basis of the Act. In other words, LGU WMPs should not be adopted if they do not contain all of the required parts; adoption should indicate that the WMP contains all the required parts. However, the Implementation Decision only monitors the implementation of some elements of LGU WMPs Table 3.

| Table 3 Comparison of WMP-Prescribed Content for LGUS and the City of Zagreb with Implementation Decision Measures |

|

|---|---|

| LGU Plan Minimal Content | WMP/Implementation Decision |

| 1. Analysis and assessment of the situation and waste management needs in the area of LGUs, i.e., the City of Zagreb, including the achievement of targets | |

| 2. Data on types and quantities of waste produced, separately collected waste, disposal of municipal and biodegradable waste, and achievement of targets | Monitoring the share of biodegradable waste in mixed municipal waste (indicator: LGU/year) |

| 3. Data on types and quantities of waste produced, separately collected waste, disposal of municipal and biodegradable waste and achievement of targets | |

| 4. Data on disposal locations and waste removal | |

| 5. Measures necessary to achieve the targets of reducing or preventing the generation of waste, including educational and informational activities and waste collection activities | Inclusion of measures to prevent waste generation in LGUs’ waste management plans Number of plans that include waste prevention measures (556 target values) |

| 6. General measures for waste management, hazardous waste, and special categories of waste | |

| 7. Measures of collection of mixed municipal waste and biodegradable municipal waste | |

| 8. Measures of separate collection of waste paper, metals, glass and plastic, and large (bulk) municipal waste | |

| 9. List of projects important for the implementation of the Plan’s provisions | |

| 10. Organizational aspects, and sources and amounts of financial resources for the implementation of waste management measures | |

| 11. Deadlines and holders of the Plan's execution | |

Some institutional solutions seem to be designed for policy failure. Financial plans are not aligned with the WMP. Implementation is not transparent.

The national WMP anticipates implementation of the measure "Estimating the Quantity of Asbestos Waste by Counties" by the end of 2019, which would suggest undertaking a single study with county-level data. The Implementation Decision, however, calls for 21 studies, whose holders are LGUs and RGUs and the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development (until 2018 Croatian Agency for Environment and Nature - CAEN). The planned completion rate is 10 studies in 2018 and 11 in 2019, with the funding made available through combined CAEN/EPEEF/EU funds at an estimated cost of HRK2 million. Undertaken per the ID, the Ministry/CAEN would have to provide organizational capacities (staff or salaries for Ministry experts involved in this activity) and EPEEF would have to provide part of the financial resources. If so, this should be visible in their 2018 budget and in their projections for 2019; however, these activities could not be identified in the financial plans of Ministry / CAEN or the EPEEF. Waste management plans of cities and municipalities treat this WMP measure differently - some quote it and some do not. There is no clear role for towns in county studies, especially given that county authorities and the City of Zagreb are responsible for planning the location of landfills for the disposal of asbestos waste. On the other hand, according to the Ordinance on construction waste and waste containing asbestos (OG 69/16), LGUs are obliged (through correspondence, public communications, and the like) to call the owner or user of the facility in which asbestos is located to submit data on asbestos use, or obtain it themselves, and deliver it to the EPEEF. EPEEF has data, and instead CAEN was the co-holder of the study.

LGUs/RGUs and CAEN should apply for EU tenders in order to secure EU funding. However, no such tender was announced in the indicative annual plan for the publication of calls for proposals,10 so it is no wonder that WMPs of the largest cities (Zagreb, Split, Rijeka, Osijek) treat this issue differently. Zagreb (HRK100,000 in 2019) and Split (HRK80,000 in 2019) anticipate the development of studies and predict financing in accordance with the national WMP (EPEEF, CAEN and EU). Rijeka has conducted a study and submitted the results to the EPEEF in 2017, while the City of Osijek WMP does not define specific activities or estimate the cost, but makes reference to the national WMP. Such organizational solutions are not transparent and require individual city and municipality initiatives. Organizational issues and vague funding responsibilities can lead to delays in the realization of this measure and the achievement of targets, although the amount of funding itself does not represent a significant barrier to cities and municipalities.

Data Collection

The foundation for planning of the waste system is the quality of data on waste and its systematic collection. A lack of cooperation and coordination between relevant institutions (the EPEEF, and the Ministry) is reflected in the reduced integrity and reliability of data on waste and waste management, which is key for system planning. For example, the Special Waste Categories Registry is not established and the Waste Management Information System (WMIS) is delayed. There is a delay in measures related to the design and/or upgrading of applications that are part of the Waste Management Information System, partly as a result of inadequate technical capacity. Inadequate data quality can cause problems when dimensioning a waste management system. Educational and information activities (preparing guidelines, manuals, workshops, etc.) could contribute to better data quality and better data collection.

Data are regularly reported by municipal companies and waste service providers. The quality of data varies, and consequently, it does not provide a reliable basis for system planning. LGUs do not have access to or control of data entering the Waste Management Information System (WMIS) for work carried out by public service providers. Yet the incentive fee for the reduction of mixed municipal waste to be assessed beginning in 2018 is based on this data, as is planning for the number and procurement of the containers for the separate collection of municipal waste co-financed by EU funds.

Given that LGUs do not have a role in data collection and processing, but municipal companies do; the municipal companies, i.e., public service providers, should be legally permitted to procure works and services for waste management projects co-financed by EU funds.

Ensuring significant incentives and co-ordination from the national level is critical because of the under-capacity of LGUs and poor mutual cooperation, especially for the implementation of measures where there are two or more stakeholders (LGUs/RGUs). The EPEEF and RGUs support continuous and intensive coordination, advisory, technical, and financial assistance to LGUs.

Merging CAEN with MoESD undermines the independency of data processing. According to the Government’s August 2018 decision to reduce the number of agencies, institutes, funds, foundations, companies, and other legal entities holding public authority, CAEN merged into MoESD in January 2019. This restructuring has caused further delays in the improvement of the Waste Management Information System, and consequently, problems regarding adequate planning.

The Role of the Ministry of Regional Development and the Use of EU funds

The Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds sets priorities and prepares strategic and operational documents for the use of EU funds. Intensive cooperation is necessary for determining which projects will be financed by EU funds. This is particularly important not only for the program’s preparation of the 2021-2027 programming period (after 2020).

The 2014-2020 period the use of EU funds was slower than planned. The Investment Dynamics anticipated by the WMP, which are slower than the planned dynamics for achieving the targets, especially in the period 2017-2018, indicate that the delays are accounted for in the WMP. Until the end of 2017, only 17% of EU funds were committed. This point to the weaknesses in planning, and to the conclusion that a loan should be provided for the initial period of implementation.

The LGUs lack technical capacities to dimension the waste management systems, and hence, prepare projects that would provide optimum outcome with the amount of grant funds available. This implies that available funds might even be spent in the OP period; however, those would not achieve all the targets as planned. With the LGUs’ lack of financial capacity to co-finance investments, and the diminished role of the EPEEF in co-financing, further delays are expected.

Lack of Coordination and Harmonization across Ministries and Sectors

Besides a lack of vertical cooperation, there is an evident lack of horizontal co-operation and co-ordination (e.g., cooperation between MoESD and other line ministries). Insufficient cooperation makes it difficult to adopt and implement measures to establish an effective waste management system, as well as achieve the targets set. As a key example, the Act on Sustainable Waste Management, the Utility Services Act, and the Act on Local Taxes are not harmonized.

The Act on Local Taxes anticipated the replacement of utility fees, holiday home tax, and monument annuity with a real estate tax. This local tax could have been, among other things, a source of funds for the construction and maintenance of waste management infrastructure. The law was expected to come into effect from January 1, 2018, but was changed before that date and these provisions were removed in order to “allow for further consideration and seeking the best financing solutions for LGUs and to further analyze the overall revenue collection effects of local units in all segments of society."11

The Utility Services Act keeps the utility fee as a dedicated income of the LGU. However, waste management is not a utility service, so the construction of waste infrastructure cannot be financed from utility fees. At the same time, the municipal/utility service monitoring officer is responsible for supervising the application of waste management regulations, which leads to misunderstanding about institutional arrangements and reduces their transparency.

In addition, according to the Sustainable Waste Management Act,12 the representative body of LGUs may impose a designated fee on a user of public service collection of mixed municipal waste and biodegradable municipal waste. This is allowed under the Program for Construction of Municipal Waste Management Facilities. According to the Act, the Program for Construction of Municipal Waste Management Facilities is an integral part of the Program for Construction of Utility Facilities and Installations. The latter Program is adopted in accordance with the law regulating the utility services (Utility Services Act), according to which waste management is not utility service. The new Utility Services Act was adopted in July 2018 (OG 68/18). During the debate in Parliament, many shortcomings were highlighted, which could make implementation difficult (e.g., inadequate monitoring of implementation).

Misleading Incentives

According to the Law, the incentive fee for reducing the amount of mixed municipal waste should provide for financial incentives for LGUs that are progressing well towards achievement of national and EU goals. However, its design penalizes LGUs that are being proactive and successful in separate collection of municipal waste. The Regulation on Municipal Waste Management defines this fee in a way that does not consider an LGU’s degree of success in separate collection; rather, all LGU units are assessed the same financial sanctions for failing to reduce their amount of mixed municipal waste. Additionally, the Regulation defines the basics for establishing separate municipal waste collection systems that are the same for all LGUs regardless of their specific circumstances (e.g., spatial accommodation, existing infrastructure). As an example, the existing Kastijun and Mariscina WMCs have built capacities that were planned based on the waste management system existing at the locations that these centers currently cover.

Negative Public Views on Waste and Waste Management

The public’s perspective on waste management is predominantly negative, resulting in a hostile attitude towards the location of waste management facilities, from recycling yards to landfills and energy recovery plants. There is no systematic educational effort focused on the public, administration and political officials, or even waste management staff. As a rule, the public (comprising all social groups) considers waste and waste management to be a problem that should be resolved by someone else - i.e., the state, its agencies, counties, or economic entities - and somewhere else.

There is lack of confidence in national institutions;13 thus, people generally do not expect the waste management infrastructure to function properly, i.e., it will not pose an additional threat to their health and the environment. Hence, there is strong opposition towards the system’s development.

Public/social groups are only engaged when they are directly endangered or otherwise interested in resolving a certain issue. They do not propose alternative solutions, but rather oppose the proposed solution. Consequently, resolving waste issues is often challenging, as there are groups and parties with different and often conflicting interests (e.g., state bodies, local governments, businessmen, scientists, experts, associations, political parties, media, and the public).

The selection of locations for new facilities and waste management installations is particularly difficult, even when existing non-compliant landfills need remediation and closure. Reasons for this include insufficient knowledge and a lack of information on waste issues; mistrust; insufficient public participation in decision-making processes; and the lack of uniform and transparent remedies for impaired real estate value.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Croatia has insufficient capacity to create policies at the EU, national, or local level. Competencies at various governance levels (central, regional, local) are not clear. Cooperation among various institutions and bodies is insufficient. Within the present system, institutions are highly unlikely to implement necessary reforms. Political will and high-quality, cross-sectorial cooperation are essential for the establishment of an efficient waste management system that will ensure the realization of European Union goals.

Most of the waste system responsibilities are placed at the local level. Only some of 556 LGUs have the institutional, managerial, and financial capacity for sustainable waste management. Financial projections are prepared for period of three years, yet the scope of necessary investment requires a longer time horizon. Medium-term planning at the local and national level is needed so that realistic investment projections can be made. An increased role for counties in the waste management system could enhance and improve the establishment of the system. Still, the central government must provide guidance, technical support, and (co-) funding. In this regard, the coordination role and educational role of the counties is especially important, particularly considering the lack of cooperation among LGUs and the under-capacity of many LGUs.

Co-operation is lacking among MoESD, the EPEEF, LGUs and RGUs, and CAEN (i.e., the main actors in the implementation of national WMP measures). This contributes to overall non-compliance. Also, it is necessary to improve cooperation among other relevant institutions like the Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds, Ministry of Economy, and Ministry of Agriculture.

A comprehensive waste management system requires the coordination of competent bodies (e.g., MoESD, the EPEEF, RGUs/LGUs), as well as the involvement of a wider circle of stakeholders in waste management. The private sector (legal and natural persons/craftsmen) can carry out waste management activities if they meet the requirements prescribed by the Act. In addition, the public, professionals and professional associations, and other stakeholders can carry out activities that may lead to the promotion of practices and awareness, as well as encourage public participation in issues related to waste management (and decision-making).

The Waste Management Plan and the Implementation Decision introduce some measures aimed at establishing a comprehensive system and envisioning the involvement of a larger number of stakeholders, but their means for cooperation and their competence are not clearly defined.

Pilot projects should be developed and the effectiveness of cooperation planned in the WMP should be tested. Two special task forces, one with a policy-making task and the other focusing on implementation, could be a first step. The policy-making task force should have the capacity and mandate to negotiate with the EU on transposition of the waste legislation. The sole task of the second task group should be implementing EU waste management policy, focusing on implementation of measures already included in the national WMP. The communication between the task groups should generate sufficient inputs for defining negotiating positions. The task forces should have adequate decision-making competencies.

Procedures for inter-departmental cooperation and the authority as well as the responsibilities of project managers should be defined based on the results of pilot projects. Generic lists of necessary procedures in project preparation, depending on their scope and type, should be prepared. All administrative requirements should be identified and transparency of procedures intensified, thus creating preconditions for their acceleration without adversely affecting the quality of project preparation.

A significant number of the implementing measures envisaged by the Act on Sustainable Waste Management have not been prepared and adopted.

There are delays in the implementation of fees, introduction of the landfill tax, assessment of defined fees, implementation of restrictions on the disposal of biodegradable municipal waste, remediation and closure of landfills, and establishment of WMCs. Shortcomings outlined in the 2005 Strategy are still not resolved. Delays in implementation lead to increased costs (for necessary transitional measures), infringement procedures, fines, and other potential sanctions (e.g. in terms of allocation of funds in the next programming period).

An institutional and regulatory framework that is unstable due to frequent changes limits the possibility of applying regulations and the involvement of the private sector. For example, the Act on Sustainable Waste Management provides for inspection supervision in 2013 in accordance with the applicable arrangements. In 2017, amendments were made in order to align the Act with the changed organization and scope of ministries and other central state administration bodies and to suspend the work of the State Inspectorate.

It is necessary to ensure regulations are applied through better preparation and a more reasonable adjustment period. A minimum of three months’ adjustment period (from disclosure to entry into force of the new regulation) is necessary.

More intensive and systematic cooperation is necessary in several areas: when adopting regulations to avoid adopting legal provisions that are difficult to implement and which slow down the system's upgrading; when building system capacity for project preparation (including a clear definition of coverage and targets); and when monitoring implementation through the organizational strengthening of relevant state administration bodies and educational efforts.

MoESD and the EPEEF should propose new solutions based on an assessment of problems, needs, and impacts in relation to the existing situation. Such proposals should take into account that a stable, predictable, and effective regulatory and legal system enables realistic planning and provides mechanisms for dispute resolution, which can reduce risk and enable investment decisions.

Implementation of the national WMP relies significantly on EU funding. MoESD and the EPEEF are the relevant implementing bodies (PT1 and PT2). Their institutional and financial capacity is limited, with the activities for tendering of the grants slower than planned. By the end of 2017, only 16.1% of the total planned funding in the waste sector for the period 2014-2020 was committed.14

The way that funds are withdrawn reveals shortcomings in planning, which poses a risk to the establishment of an efficient, affordable, and adequate waste management system.

Absorption of EU funds for large projects is particularly poor. The need to speed up the implementation of large projects is recognized through the establishment of special procedures for strategic projects, based on a separate law (Law on strategic investments). However, this solution has had little impact on implementation.

In view of the evident implementation delays, it is necessary to re-examine the possibility of implementing planned projects and possibility of redistributing available resources, primarily for large projects.

The order for the implementation of WMP measures affects the achievement of targets. WMP priorities should be determined in terms of funding/implementation, i.e., the level of preparation and technical assistance required. This requires determining the interdependence of individual measures and, if necessary, revising their sequencing. For example, a decision on the need for energy recovery and for construction of such a facility could affect the necessary capacities of WMCs and their viability; the construction of the WMC allows for the closure of the landfill; the introduction of a landfill fee promotes the application of the "polluter pays" principle; and thus, prerequisites are created for introducing a viable waste management price that enables the construction and maintenance of adequate infrastructure.

The criteria the project must meet in order to be carried out should be defined. The participation of the private sector, NGOs, and other stakeholders in implementing the WMP should be fostered by involving a greater (and also a diverse) number of eligible applicants for co-financing from the EU, as well as by capacity-building at all levels (i.e., cities, municipalities, counties, public education, utilities).

It is necessary to create a framework (and define measures) that would trigger private investment. The introduction of the private sector into the municipal waste collection and treatment system can contribute to reducing the costs and management burden in the LGUs. LGUs require technical, financial and administrative capacities to clearly define the quality criteria and the scope of public services, preparation, procurement, and contracting as well as effective public procurement.

Public procurement presents difficulties for implementation, so strengthening the public procurement capacity is one measure that can accelerate implementation.

Fragmented implementation of measures, and the provision of a separate waste collection and treatment system, without timely access to adequate recycling facilities and recycled product markets, pose a risk that could lead to a costly and dysfunctional system (high operational costs of an over-capacitated and inefficient system) that fails to fulfill European Union targets.

The planning and implementation of separate collection and treatment of municipal waste needs to be considered from a broader perspective, rather than localized at the level of individual LGUs. At the same time, when setting up a waste management system, it is necessary to take the specifics into account and to define the implementation measures that depend on them. For example, when establishing separate collection of municipal waste, it is necessary to consider the specifics of a particular area (geography, number of settlements, role of tourism, etc.) in order to evaluate and plan for the extent of environmental impact and financial costs as well as the feasibility of establishing a certain collection model in a particular area.

Since no reliable data is available that would allow the system’s performance to be evaluated, differences in statistical data between the EPEEF and the Ministry should be revised and, to the extent possible, eliminated. This would help facilitate comparison and analysis, and preparation of adequate measures.

New European targets for waste packaging and municipal waste recycling and re-use, defined by amendments to the Waste Directive and Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive, enter into force and must be transposed into national legislation in 2020. They are stricter than current targets. Croatia needs to implement comprehensive sector reform in order to develop the capacity to comply with EU regulations. Failing to do so will lead to the initiation of infringement procedures.

When setting up a waste management system, it is necessary to take into account the "circular economy package" guidelines. This is also particularly important in setting up WMCs in terms of defining the required capacities and determining the technology.

Thus, reform of the territorial and organizational structure of the Republic of Croatia should consider institutional, technical, and financial criteria and not only political criteria. The Council Recommendations on the National Program for the Reform of the Republic of Croatia for 2017 should be implemented, primarily those related to shortcomings in public administration, the complex business environment, the slow implementation of the anti-corruption strategy, restrictive regulations in key infrastructure sectors, and the strong state presence in the economy.

FootNotes

- As of January 2019. HAOP, 354 LGUs have WMPs based on current law. In addion, 54 LGUs have prepared WMPs that have not expired yet, based on previous version of law. There are 149 LGUs without WMP. Complete information available at http://www.haop.hr/hr/tematska-podrucja/otpad-i-registri-oneciscavanja/gospodarenje-otpadom/izvjesca

- Local self-government units design municipal waste management system through their local waste management plans, while the role of counties is more formal in character - giving consent that local waste management plans align with the national WMP.

- MZOE (2018). Godišnje izvješce o radu za 2017. godinu. Zagreb, svibanj 2018. http://www.mzoip.hr/doc/godisnje_izvjesce_o_radu_za_2017_godinu.pdf. Of 88 proceedings against Croatia, 19 refer to the waste sector. https://ec.europa.eu/atwork/applying-eu-law/infringements-proceedings/infringement_decisions/?lang_code=en

- http://www.haop.hr/hr/tematska-podrucja/otpad-i-registri-oneciscavanja/gospodarenje-otpadom/izvjesca

- Of 88 proceedings against Croatia, 19 refer to the waste sector.

- http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/scoreboard/performance_by_member_state/croatia/index_en.htm#maincontentSec1

- Croatian Government (2017).

- According to the Treaty, all non-compliant landfills should be closed or be in compliance with EU policy by the end of 2018, while the Act required a ban on non-compliant landfills by the end of 2017.

- The costs relate to investment costs: they were calculated solely for benchmarking purposes. More details are available in the Financial chapter.

- Croatian Competition Agency (2015).

- MRRFEU (2018).

- Government (2017).

- Article 33, paragraph 3.

- According to the latest Eurobarometer survey (fieldwork from May 2017), Croatia is among the countries of the EU whose citizens tend not to trust their national government. The share of people in Croatia who tend not to trust the national government is 72% (Special Eurobarometer461).

- State Audit Office. Report on the Effective Audit of Efficiency of Implementation of the Operational Program Competitiveness and Cohesion 2014 - 2020.

References

CCA. (2015). Opinion, law on sustainable waste management.

European Commission. (2016). Performance by member states .

European Commission. (2017). Special Eurobarometer 461. Designing Europe’s future: Trust in institutions. Globalization. Support for the euro, opinions about free trade and solidarity.

HAOP. (2018). HAOP budget for 2018.

MRRFEU (2018). Indicative annual plan for publishing calls for project proposals.

Government. (2017). Bill on amendments to the law on sustainable waste management, with the final bill.

MZOE.(2018). Annual work report for 2017. Zagreb.

MZOE. (2018a). Letter dated March 9, 2018 on the adoption of the Decision on the manner of providing public services for the collection of mixed and biodegradable municipal waste. Class 351-01 / 17-01 / 576, Reg. No. 517-01-18.-9.

Partnership agreement.(n.d.).

Waste Management Strategy of the Republic of Croatia, OG 130/2005. (2005).

Received: 24-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10437; Editor assigned: 27-Jan-2022, PreQC No JLERI-21-10437 (PQ); Reviewed: 15- Feb-2022, QC No. JLERI-21-10437; Revised: 24-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10437 (R); Published: 10-Mar-2022.